Abstract

Background

Older patients in hospital may be unable to maintain hydration by drinking, leading to intravenous fluid replacement, complications and a longer length of stay. We undertook a systematic review to describe clinical assessment tools which identify patients at risk of insufficient oral fluid intake and the impact of simple interventions to promote drinking, in hospital and care home settings.

Method

MEDLINE, CINAHL, and EMBASE databases and two internet search engines (Google and Google Scholar) were examined. Articles were included when the main focus was use of a hydration/dehydration risk assessment in an adult population with/without a care intervention to promote oral hydration in hospitals or care homes. Reviews which used findings to develop new assessments were also included. Single case reports, laboratory results only, single technology assessments or non-oral fluid replacement in patients who were already dehydrated were excluded. Interventions where nutritional intake was the primary focus with a hydration component were also excluded. Identified articles were screened for relevance and quality before a narrative synthesis. No statistical analysis was planned.

Results

From 3973 citations, 23 articles were included. Rather than prevention of poor oral intake, most focused upon identification of patients already in negative fluid balance using information from the history, patient inspection and urinalysis. Nine formal hydration assessments were identified, five of which had an accompanying intervention/ care protocol, and there were no RCT or large observational studies. Interventions to provide extra opportunities to drink such as prompts, preference elicitation and routine beverage carts appeared to support hydration maintenance, further research is required. Despite a lack of knowledge of fluid requirements and dehydration risk factors amongst staff, there was no strong evidence that increasing awareness alone would be beneficial for patients.

Conclusion

Despite descriptions of features associated with dehydration, there is insufficient evidence to recommend a specific clinical assessment which could identify older persons at risk of poor oral fluid intake; however there is evidence to support simple care interventions which promote drinking particularly for individuals with cognitive impairment.

Trial registration

PROSPERO 2014:CRD42014015178.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Older adults are susceptible to dehydration due to acute and chronic health problems, which impair thirst, reduce the ability to drink sufficiently and/or increase urinary, skin and respiratory fluid loss [1]. During hospitalisation negative fluid balance often accompanies infection and is independently associated with poorer outcomes [2–5], longer length of stay and greater costs [6–8]. In England the National Institute for Healthcare and Care Excellence has estimated that the annual impact from acute kidney injury is up to £620 million [7] and that 12,000 cases could be avoided by more pro-active fluid management amongst vulnerable groups such as older adults. Specific associations with dehydration have already been described with acute stroke [9], and admission from a long term care setting [10]. Although it is a clinical priority to recognise and address risks of insufficient oral fluid intake, there is no standardised nurse-led assessment or formal bedside response protocol commonly applied. A recent Cochrane review [11], of studies to identify impending and current water loss in an older people recommended that for clinical practice “there is no clear evidence for the use of any single clinical symptom, sign or test of water-loss dehydration in older people. Where healthcare professionals currently rely on single tests in their assessment of dehydration in this population this practice should cease because it is likely to miss cases of dehydration (as well as misclassify those without water-loss dehydration).” Previous studies have recommended combining various data items to identify individuals, who may need fluid support interventions. Some studies have often confused a risk of inadequate fluid intake with characteristics already indicating a dehydrated state or relied upon serial laboratory measures of renal function and osmolality [2, 12]. In the absence of a single test/symptom based upon an objective reference standard of hydration status, our aim was to look qualitatively at the evidence for any assessment (including multiple combinations of factors) and matching intervention which could be easily used at the bedside specifically to reduce the risk of dehydration (not to identify an already dehydrated state). This would not be restricted to studies attempting to validate against laboratory measures of fluid status. In order to make recommendations regarding care processes during hospitalisation, studies would be selected from institutional settings, including care homes.

Methods

Using PRISMA guidelines [13] articles published in English were sought where the main focus was use of a hydration/dehydration assessment in an adult population with/without a care intervention to promote oral hydration. Review articles were included where a new assessment tool was developed as a result of findings. Articles were excluded which described single case reports, laboratory results only, technology which was not integrated into a clinical score e.g. bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) or non-oral fluid replacement in patients who were already dehydrated. Interventional studies were included if the intention was specifically to promote oral hydration rather than nutritional intake in general.

A search of electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL) was conducted using keywords: dehydration, prevention, assessment, screening, hospitals and care homes. The reference lists of identified papers were cross-referenced for new articles. Grey literature (non published academic work, hospital protocols and existing dehydration assessment tools) was sought through Google and Google Scholar. Interventional studies were included if the intention was specifically to promote oral hydration rather than nutritional intake in general. A structured data extraction and quality appraisal form was used for information extraction including: design, population and identification, method of data collection, results, ethical considerations, key ideas and author’s conclusions [14–16]. The first author (LO) screened initial titles and abstracts. Two authors (LO,CP) independently reviewed full text articles. Differences were resolved in scheduled meetings. Due to the mixed nature of the studies and uncertainties about the generalizability of different settings, results are presented as a narrative synthesis and no additional analysis was performed. The protocol was registered with the PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO 2014:CRD42014015178). Fuller details of the search methods are available from the corresponding author.

Results

Search results

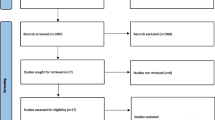

Figure 1 describes the study selection process. A total of 3973 articles were identified, after removing duplicates 3893 remained. Out of 3893 retrieved articles, 3805 were excluded by title and/or abstract, 69/88 full text articles were excluded because they were duplicate or single case reports, did not focus on dehydration prevention or oral fluid risk management and/or only considered additional non-oral fluid replacement strategies for patients who were already known to be dehydrated. Within the reference lists of the remaining articles a further four relevant papers were identified.

Table 1 describes a summary of the extracted data. Of the 23 articles there were eight intervention studies, six non-systematic literature reviews, two guidelines, one assessment proposal, two audits, one multi-phase project summary and three surveys. Publication dates ranged from 1984 to 2016. Countries of origin were USA (nine), UK (eight), Australia (five) and Italy (one). Comparison of quality was challenging due to the variable nature of the articles; however most had a clear stated aim and identified their target setting. The search did not identify adequately powered randomised controlled trials and large prospective observational studies. The individual risk factors for poor hydration reported across the 23 included articles are summarised below. To describe the clinical context of each assessment or intervention, each article has then been placed into one of five groups: identification checklist/chart (five), identification checklist/chart with care intervention (five), identification by urinary inspection (two), promotion of oral intake (four), professional knowledge/awareness improvement (seven), as seen in Table 1.

Individual risk factors

The most common clinical factors associated with dehydration reported by the different literature sources are listed in Table 2. Physical patient attributes were used as indicators of fluid balance status in nine articles [17–25] including dry mouth, lips, tongue, eyes and/or change in skin turgor. Vivanti [17] reported that amongst 130 clinical variables, tongue dryness was most strongly associated with poor hydration status with a sensitivity of 64%, (95% CI 54–74%) and specificity of 62%, (95% CI 52–72%); however this was used as an indicator of dehydration rather than as an assessment of risk of poor oral fluid intake in patients who did not yet require fluid supplementation.

Oral fluid intake barriers were highlighted in eight articles [17–19, 21, 23, 26–28] including swallowing difficulties, physical assistance needed to drink and frequent spills, there was no consensus regarding a definition or bedside assessment process. The inclusion of recent diarrhoea and/or vomiting within a risk assessment was suggested by five articles [19–21, 23, 24]; however these acute symptoms are likely to prompt intravenous fluid replacement on admission to hospital and may not be helpful as indicators that further support for drinking is required.

Confusion or change in mental state was an indicator of risk in 11 articles [19–26, 28–30]. Mentes and Wang [26] reported that 61/133 dehydrated patients had a Mini Mental State examination (MMSE) score of less than 24/30, of whom 40 had dementia. During an intervention with residents receiving verbal prompts, Simmons [30] identified that those with greater cognitive impairment demonstrated a greater fluid intake response.

Low blood pressure or a weak pulse was highlighted in seven articles [18–21, 23, 24, 31] as a useful indicator of dehydration already being present. Vivanti [18] found that a fall in systolic blood pressure whilst standing was separately associated with hydration status. Although fever was described as an independent factor, there was no agreed definition or separation from possible effects upon blood pressure and mental state [18, 20, 21, 23, 24].

An increased risk associated with diuretics was discussed in seven articles [18–21, 23, 26, 28]. Mentes and Wang [26] found that 51/133 dehydrated patients were taking diuretic agents, the results showed that further scrutiny was needed as a negative association with poor oral fluid intake was found during factor analysis. The authors suggested that diuretics may also stimulate fluid consumption relative to the increased output.

Fluid intake volume was used as a risk indicator by nine articles [19–22, 24, 25, 27, 29, 32]. In the South Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust, Food First tool (“GULP”) [20] an individual’s overall risk score was weighted by their 24 h oral intake: zero points >1600 ml; one point 1200 ml–1600 ml; two points < 1200 ml. In Keller’s [32] audit of care homes the protocol for residential care sites for a patient deemed at risk of dehydration was an intake < 1600 ml per 24 h. Kositzke, Zembrzuski and NHS East of England [21, 22, 24] proposed guidelines that staff should encourage a daily intake of at least 1500 ml or 30 ml/kg for patients aged over 60. Similarly Wotton [19] recommended calculating daily intake requirements at 30 ml/kg whilst taking into account co-morbidities and the on-going response to hydration measures. It was not surprising that urine volume and colour was also reported as an important association with dehydration [20, 21, 24, 31, 33], there was no agreement about the length of time for observation or thresholds for changing the fluid support strategy.

Identification checklist/chart

A formal checklist for dehydration risk was described by ten articles. Eight are summarised in Table 3. Keller [32] has not been included as individual data items were not listed and Bulgarelli [34] used the Mentes and Wang [26] checklist, which is described.

Table 3 describes the checklists according to three component categories: history, observation and bedside test. There was a large variation in the size and complexity. In patient history, feeling thirsty, medications and poor mobility/falls/weakness were included in a combination of seven of eight assessments for each factor, whilst diarrhoea/vomiting and repeated UTI’s/infections were included in a combination of five of eight assessments. In observation, blood pressure/pulse, confusion, dry mouth/tongue/eyes/skin and low body weight/malnutrition were included in a combination of seven of eight assessments, whilst 24 h fluid intake/output was included in a combination of six and fever included in a combination of five assessments. Six of the eight assessments included investigating urine colour as a bedside test in the assessment of dehydration risk.

Of the ten articles, five [17–19, 26, 34], did not suggest a clinical response protocol or recommendations for patients at risk. Although Wotten [19] conducted a review of literature and created a risk assessment, there was no clear method described for the selection of included literature and no evaluation.

Mentes and Wang [26] conducted a retrospective analysis to make adjustments to an existing Dehydration Risk Appraisal Checklist (DRAC) containing 40 items including age, health conditions, medications, laboratory results and intake behaviours. This was reduced to 17 questions by conducting an analysis on two previous studies of 133 participants. Overall there was low to moderate association with dehydration. The authors concluded that the analysis supported clinical use of the DRAC whilst highlighting the restricted interpretation due to the small sample size and the additional importance of applying contextual information. Bulgarelli [34] also evaluated the DRAC, a small sample of 21 patients were scored using the checklist within 3 days of admission. Scores on the DRAC did not significantly change between admission and discharge.

Vivanti [18] looked at over 40 clinical, haematological and urinary biochemical parameters employed by medical officers during dehydration assessment in hospital. There were no serial measurements. The parameters were identified through literature; interviews and focus groups. The dominant factor was tongue dryness (OR 4.42; 95% CI 0.86 to 26.10), which would mainly indicate a need for current additional fluid replacement rather than a future risk of poor intake, although it would be expected that there is an overlap between these patient groups.

Identification checklist/chart with care intervention

An identification checklist with a specific or general care intervention was described by the remaining five articles [20–23, 32]. The GULP tool [20] recorded a score from 0 to 7 points for three categories (24 h fluid intake; urine colour; clinical risk factors for dehydration) and directed the user to present the patient with a matching hydration management plan. The plan included providing information leaflets, engaging the patient in self-monitoring of urine and verbal prompts. The plan development was not reported and there were no data describing its use.

NHS East of England [22] developed a fluid care bundle including an audit tool, patient information and nine principles to assist with fluid management: focus on individual patient needs; assess all patients; facilitate hydration; maintain accurate fluid balance; provide guidance documents for staff; provide information leaflets for patients and relatives; communicate relevant changes in the patient condition; perform fluid assessment audit; analyse fluid related adverse events. No data were presented regarding the bundle impact upon practice.

Zembrzuski and Mentes [21, 23] both summarised published literature to recommend development of local checklists, implementation approaches and individual management plans which included a statement regarding the frequency that patients should be offered drinks. The method of literature selection was not reported and management plans were not tested in clinical practice.

Keller [32] conducted an audit in nursing homes to assess the implementation of a hydration management protocol introduced in three phases: 1) document a dehydration risk, 2) monitor fluid intake for those at risk and 3) aim for >1600 ml intake per 24 hr period. In the first phase 96 records were audited. Due to funding restrictions only 15 records were subsequently examined. Results showed an improvement in compliance for risk documentation (40 to 100%) but no patients achieved the standard set for phases two and three.

Identification by urinary inspection

Identification of dehydration by urine characteristics was described by two articles [33, 35]. Mentes [33] found significant correlations between researcher ratings on a urine colour (Ucol) chart and urine specific gravity (Usg) for 98 nursing home residents. They proposed that Ucol alone could only be used to cautiously assess hydration status in older adults with adequate renal function (Cockcroft-Gault estimated creatinine clearance [CrCl] values of > or =50 ml/min) as the inter-rater reliability was average to good.

Rowat [35] conducted a small observational study to assess if bedside Usg and Ucol charts were useful indicators of dehydration following acute stroke. Results were compared to urine refractometer readings and routine blood urea:creatinine ratios for 20 patients over a 10 day period. Nine patients developed clinical symptoms of dehydration according to nurse opinion, and although there was good agreement with urine refractometer readings, authors concluded that bedside urine inspection did not provide an early warning of dehydration according to routine U:C ratio measurements.

A further six articles included measurement of Usg or Ucol as indicators of dehydration within their recommendations or tools, no new data were presented [20–22, 24, 31, 33].

Promotion of oral intake

Wakeling [27] introduced a “hands free” hydration plan for 313 patients in hospital: a bottle was clipped onto the bed with a flexible bite valve hose or patients with greater independence were provided with a plastic sports bottle. In a before and after study using a convenience sample of 313 patients (171 before and 142 during implementation) there was a reduction in length of stay (41 vs. 33 days), dehydration (31 vs. 28 patients) and infections (1 vs. 0 patients). No statistical analysis was performed. The documentation of fluid intake also improved, creating uncertainty about the mechanism of action of the un-blinded intervention.

In nursing homes, regular prompts to drink by a healthcare attendant with or without a beverage cart reduced the frequency of dehydration observed by three studies [29, 30, 36]. Robinson also found a reduction in falls, UTI’s and the use of laxatives. Simmons reported that 81% of participants showed small increases in their average daily fluid intake in response to additional verbal prompts, particularly residents with greater cognitive impairment. 21% also required preference elicitation to increase their intake, mainly amongst residents with less cognitive impairment.

Professional knowledge/awareness improvement

The relevance of professional knowledge/awareness was described by seven articles [24, 25, 28, 31, 37–39]. Beattie [39] reported a mean score of 4.7/10 from a cross sectional survey of 76 employees to assess knowledge regarding the nutritional needs of nursing home residents. Higher scores were obtained for questions relating to risk factors associated with malnutrition, less than half of respondents regularly recorded fluid intake and only 15% exhibited correct knowledge of fluid requirements.

The English National Health Service (NHS) Nutrition Now Campaign, was promoted by the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) and Royal College of Nursing (RCN) comprising 20 points to encourage hydration, fact sheets, care pathway checklists and general advice. There was no supporting information regarding the development of the fact sheets or their impact [38].

Survey results from 53 lead nurses (a 33% response rate) undertaken by NHS Kidney Care regarding the use of a poster campaign to promote hydration, showed that although 70% of respondents had displayed the posters, only 45% had a policy to monitor hydration, 15% felt their local policy needed updating, and 11% did not have a policy. Respondents identified hydration monitoring challenges including compliance with documentation, keeping practice up to date and staff awareness [37].

Discussion

Prevention of dehydration amongst vulnerable populations remains a healthcare priority. The National Institute for Healthcare and Clinical Excellence [7] proposed that 12,000 cases of acute kidney injury could be avoided with pro-active fluid management. Pash [6] found significant differences in costs and length of stay associated with dehydration in hospital ($33,945 vs. $22,380 and 12.9 vs. 8.2 days). Nursing assessments are routinely used to document a risk of pressure ulcers and malnutrition, so it is surprising that there is no standardised assessment to identify older persons at risk of inadequate fluid intake following a change in health status or care setting.

The results of our review confirm that dehydration prevention activities are not informed by strong evidence, and most studies have focused upon identification of patients who are already in negative fluid balance. Some authors described statistical isolation of characteristics associated with dehydration. Their conclusions were limited due to the small sample size, unclear environmental context, and lack of an accompanying response protocol to demonstrate clinical value. They reported challenges when balancing the practicality of an effective, single bedside, dehydration risk assessment against the number of factors which may be relevant for different patient groups, across different settings. Therefore it is currently not possible to recommend a specific assessment. Previous reviews [2, 11] found that there was no ideal single combination of risk factors and to avoid dehydration recommended the use of routine fluid balance monitoring combined with, improvements in beverage choice, staff awareness and assistance with toileting (to prevent the avoidance of drinking). The reliability and impact for resources of performing long term routine fluid balance monitoring on all patients has not been evaluated and may not be necessary if there is better recognition and targeting of vulnerable groups.

We did not include in our review, studies which were evaluating new technology to assess current fluid status, as our focus was prediction of poor fluid intake using clinical information at the bedside. The recent Cochrane [11] review has suggested that further study in this area may be useful, for example, BIA at resistance of 50 kHz of total body water. In terms of screening for impending water loss dehydration the Cochrane review found that potentially useful tests were missing some drinks between meals and expressing fatigue, whereas it was not useful to observe urinary measures, orthostatic hypotension, skin turgor, capillary refill, dry mouth assessments, sunken eyes, thirst and headache. It has recommended that some of this information could be combined to contribute towards a useful predictive instrument, but further research is required. During routine care at the bedside, pulse volume and blood pressure readings can provide an opportunity to identify some patients with dehydration; these also reflect current health state and may not separately indicate a risk of poor oral intake. An intake record over a 24 h period was also recommended as helpful for recognising patients at risk, but passive observation alone could lead to delayed intervention and increased use of intravenous fluids. Even after staff training, fluid balance recording can be incomplete particularly for patients with cognitive impairment [27]. Although a statistical association in a single setting has been demonstrated between dry mucosal membranes and objective measures of fluid status, this alone would not necessarily avoid the use of interventions such as intravenous fluid replacement. Examination of urine characteristics as a bedside assessment does not appear to be of additional value.

The single most common risk factor reported with some evidence for a matching behavioural intervention was change in mental state. Nearly half of the patients in the population studied by Mentes [26] scored less than 24 on the MMSE, and in development of a risk assessment Wotton [19] highlighted the importance of papers describing a link between dehydration and poor cognitive abilities. Simmons [30] found that patients with cognitive impairment consumed more fluids after an increase in verbal prompts, whilst Robinson [29] reported that using brightly coloured cups and beverages, with different tastes and temperatures was well received.

The care interventions identified appear to indicate that the provision of extra opportunities such as a beverage cart to prompt and/or receive drinks is a modifiable factor in the maintenance of hydration. These simple interventions would be easy to implement and lend themselves to further research, ideally with a cluster trial design to control for clinical service and population variations. With the introduction of nutritional assistants onto some NHS hospital wards, the wider short and long term impact on dehydration prevention could be investigated [40].

Although there is evidence that healthcare staff knowledge about fluid requirements and hospital policies could be improved, behavioural approaches driven by individual patient assessment and local audit, are more likely, to be more effective in changing care delivery than simply providing more information to staff or short term national campaigns [41].

The mixture of settings, terminology and observation/ intervention approaches used by articles identified from the search strategy, provided a challenge when summarising the available evidence and guidance, and we have attempted to give the results clinical relevance. Due to the specific focus upon fluid intake, we cannot be sure that relevant information was not included from research with a more nutritional focus. We concentrated upon institutional settings as this would have the greatest relevance for patients at highest risk of dehydration, but it is possible that there may also be literature relating to maintaining hydration in the community.

Conclusion

The clinical assessment of dehydration status and risk has been promoted by researchers, policy makers and health improvement agencies but without a co-ordinated or evidence-based approach. Individuals with cognitive impairment are at greater risk and may respond to increased opportunities and support for drinking. Urine inspection does not appear to be of routine value. Simple care interventions to encourage oral fluid intake can be effective, to save resources these should be targeted at highest risk groups identified, particularly individuals with cognitive impairment. There is a need to emphasize the importance of hydration, making it a collective responsibility through staff education, clinical documentation, and hospital policy and audit systems.

Abbreviations

- BIA:

-

Bioelectrical impedance analysis

- DRAC:

-

Dehydration risk appraisal checklist

- MMSE:

-

Mini mental state examination

- NHS:

-

National health service

- NPSA:

-

National patient safety agency

- RCN:

-

Royal College of nursing

- Ucol:

-

Urine colour

- Usg:

-

Urine specific gravity

References

Thomas DR, Cote TR, Lawhorne L, et al. Understanding clinical dehydration and its treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9:292–301.

Hodgkinson B, Evans D, Wood J. Maintaining oral hydration in older adults: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Pract. 2003;9:19–28.

Weinberg AD, Minaker KL, Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. Dehydration: evaluation and management in older adults. JAMA. 2005;274:1552–6.

Himmelstein DU, Jones AA, Woolhandler S. Hypernatremic dehydration in nursing home patients: an indicator of neglect. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31:466–71.

Wolff A, Stuckler D, McKee M. Are patients admitted to hospitals from care homes dehydrated? A retrospective analysis of hypernatraemia and in-hospital mortality. J R Soc Med. 2015;0:1–7.

Pash E, Parikh N, Hashemi L. Economic burden associated with hospital post-admission dehydration. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38 Suppl 2:S59–64.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. CG169. Acute kidney injury: Prevention, detection and management of acute kidney injury up to the point of renal replacement therapy. 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg169/resources/acute-kidney-injury-prevention-detection-and-management-35109700165573. Accessed 12 Jan 2015.

Imison C, Poteliakhoff E, Thompson J. Older people and emergency bed use. London: The King’s Fund; 2012. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/older-people-and-emergency-bed-use. Accessed 19 Jan 2015.

Rowat A, Graham C, Dennis M. Dehydration in hospital-admitted stroke patients: detection, frequency, and association. Stroke. 2012;43:857–9.

Hooper L, Bunn DK, Downing A, Jimoh FO, Groves J, Free C, Cowap V, Potter JF, Hunter PR, Shepstone L. Which Frail Older People Are Dehydrated? The UK DRIE Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci first published online November 9, 2015 doi:10.1093/gerona/glv205

Hooper L, Abdelhamid A, Attreed NJ, Campbell WW, Channell AM, Chassagne P, et al. Clinical symptoms, signs and tests for identification of impending and current water-loss dehydration in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD009647. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009647.pub2/full. Accessed 22 Sept.

Bunn D, Jimoh F, Howard Wilsher S, Hooper L. Increasing fluid intake and reducing dehydration risk in older people living in long term care: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:101–13.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. 2015. http://www.systematicreviewsjournal.com/content/4/1/1. Accessed 9 Feb 2015.

Gurwitz JH, Sykora K, Mamdani M, Streiner DL, Garfinkel S, Normand SLT, Anderson GM, Rochon PA. Reader’s guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 1. Role and design. BMJ. 2005;330(7496):895–7.

Mamdani M, Sykora K, Li P, Normand SLT, Streiner DL, Austin PC, Rochon PA, Anderson GM. Reader’s guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ. 2005;330(7497):960–2.

Normand SLT, Sykora K, Li P, Mamdani M, Rochon PA, Anderson GM. Readers guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 3. Analytical strategies to reduce confounding. BMJ. 2005;330(7498):1021–3.

Vivanti AP, Harvey K, Ash S. Developing a quick and practical screen to improve the identification of poor hydration in geriatric and rehabilitative care. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50(2):156–64.

Vivanti AP, Harvey K, Ash S, Battistutta D. Clinical assessment of dehydration in older people admitted to hospital. What are the strongest indicators? Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;47:340–55.

Wotton K, Crannitch K, Munt R. Prevalence, risk factors and strategies to prevent dehydration in older adults. Contemp Nurse. 2008;31:44–56.

Food First team, part of SEPT Community Health Services Bedfordshire. GULP tool. 2012. http://www.sept.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/GULP-Dehydration-risk-screening-tool.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec 2014.

Zembrzuski CD. A three-dimensional approach to hydration of elders: administration, clinical staff, and in-service education. Geriatr Nurs. 1997;18(1):20–6.

NHS East of England. Adult intelligent fluid management bundle. 2011. http://www.harmfreecare.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/In-Action-Direct-Upload-EOE-3.pdf. Accessed 8 Dec 2014.

Mentes JC, Iowa-Veterans Affairs Nursing Research Consortium. Hydration management protocol. J Gerontol Nurs. 2000;26(10):6–15.

Kositzke JA. A question of balance dehydration in the elderly. J Gerontol Nurs. 1990;16(5):4–11.

Royal College of Nursing Nutrition Now Campaign. Drink to good health. Nurs Stand. 2007;22(2):17–21.

Mentes JC, Wang J. Measuring risk for dehydration in nursing home residents. Evaluation of the dehydration risk appraisal checklist. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2011;4(2):148–56.

Wakeling J. Improving the hydration of hospital patients. Nurs Times. 2011;107(39):21–3.

Mentes JC, Kang S. Evidence-based practice guideline: hydration management. J Gerontol Nurs. 2013;39(2):11–9.

Robinson SB, Rosher RB. Can a beverage cart help and improve hydration? Geriatr Nurs. 2002;23(4):208–11.

Simmons SF, Alessi C, Schnelle JF. An intervention to increase fluid intake in nursing home residents: prompting and preference compliance. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:926–33.

McIntyre L, Munir F, Walker S. Developing a bundle to improve fluid management. Nurs Times. 2012;108(28):18–20.

Keller M. Maintaining oral hydration in older adults living in residential aged care facilities. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2006;4:68–73.

Mentes JC, Wakefield B, Culp K. Use of a urine colour chart to monitor hydration status in nursing home residents. Biol Res Nurs. 2006;7(3):197–203.

Bulgarelli K. Proposal for the testing of a tool for assessing the risk of dehydration in the elderly patient. Acta Biomed for Health Professions. 2015;86(S.2):134–41.

Rowat A, Smith L, Graham C, Lyle D, Horsburgh D, Dennis M. A pilot study to assess if urine specific gravity and urine colour charts are useful indicators of dehydration in acute stroke patients. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(9):1976–83.

Spangler PF, Risley TR, Bilyew DD. The management of dehydration and incontinence in nonambulatory geriatric patients. J Appl Behav Anal. 1984;17(3):397–401.

NHS Kidney Care. Evaluation of the hydration matters poster campaign in acute hospital trusts. An interim report. 2012. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130802100747/http://www.kidneycare.nhs.uk/our_work_programmes/patient_safety/hydration/hydration_matters_campaign_evaluation/#. Accessed 10 Dec 2014.

National Patient Safety Agency and Royal College of Nursing. Water for health: Hydration best practice toolkit for hospitals and healthcare. 2007. https://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/70374/Hydration_Toolkit_-_Entire_and_In_Order.pdf. Accessed 15 Dec 2014.

Beattie E, O'Reilly M, Strange E, Franklin S, Isenring E. How much do residential aged care staff members know about the nutrional needs of residents? Int J Older People Nurs. 2014;9(1):54–64. doi:10.1111/opn.12016.

Rossiter F, Roberts H. Benefit of using volunteers for mealtime assistance. Nurs Times. 2015;111:12,22–23.

Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Johnston M, Pitts N. Changing the behaviour of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(2):107–12.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank The Health Foundation for their support in funding for the research. The Health Foundation had no input into the design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data or in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by The Health Foundation (GIFTS lD:7288).

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data can be found within the manuscript. For a more detailed description of the search strategy please see Additional file 1. Any further information can be found by application to the corresponding author.

Authors’ contributions

LO and CP participated in the design of the study. LO carried out the literature search. LO and CP reviewed articles for data extraction and quality appraisal. LO and CP drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Search strategy – Provides the search strategy followed for MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL databases (DOCX 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Oates, L.L., Price, C.I. Clinical assessments and care interventions to promote oral hydration amongst older patients: a narrative systematic review. BMC Nurs 16, 4 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-016-0195-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-016-0195-x