Abstract

Background and Aims

Shared decision making (SDM) and advance care planning (ACP) are important evidence and ethics based concepts that can be translated in communication tools to aid the treatment decision-making process. Although both have been recommended in the care of patients with risks of complications, they have not yet been described as two components of one single process. In this paper we aim to (1) assess how SDM and ACP is being applied, choosing patients with aortic stenosis with high and moderate treatment complication risks such as bleeding or stroke as an example, and (2) propose a model to best combine the two concepts and integrate them in the care process.

Methods

In order to assess how SDM and ACP is applied in usual care, we have performed a systematic literature review. The included studies have been analysed by means of thematic analysis as well as abductive reasoning to determine which SDM and ACP steps are applied as well as to propose a model of combining the two concepts into one process.

Results

The search in Medline, Cinahl, Embase, Scopus, Web of science, Psychinfo and Cochrane revealed 15 studies. Eleven describe various steps of SDM while four studies discuss the documentation of goals of care. Based on the review results and existing evidence we propose a model that combines SDM and ACP in one process for a complete patient informed choice.

Conclusion

To be able to make informed choices about immediate and future care, patients should be engaged in both SDM and ACP decision-making processes. This allows for an iterative process in which each important decision-maker can share their expertise and concerns regarding the care planning and advance care planning. This would help to better structure and prioritize information while creating a trustful and respectful relationship between the participants. PROSPERO 2019. CRD42019124575

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Modern ethical codes recommend effective communication, trust and respect for ones’ dignity as some of many important requirements for a patient–clinician relationship [1,2,3]. As patients have distinct personalities, character, experiences, disease specific situations and cultural backgrounds [3], they also have different needs regarding how their autonomy is best supported.

According to Beauchamp and Childress, autonomous patients can choose and act intentionally, with understanding, and without controlling influences that determine their actions [4]. As individuals may not have the resources to make fully autonomous decisions in every situation, or may not want to decide on their own, the concept of relational autonomy was proposed. It emphasizes that autonomous choices are generally achieved or realized over time in the context of positive and negative social relations, and accepts various modes of patient engagement and empowerment within the decision-making process [5]. This approach stresses the importance of having collaborative dynamics in the relationship between patients and other key decision-makers. Shared decision-making (SDM) and advance care planning (ACP) are two evidence and ethically based concepts. They foster patient autonomy by engaging patients, their relatives and healthcare professionals (HCP) in the decision-making process. Both concepts are often described as best practice models and are included in medical curricula (e.g. CANMEDS [6]) and guidelines of medical professions (e.g. AHA [7]).

SDM is a two-way information process between HCPs and patients, sharing medical and risk information as well as preferences and concerns to reach the best individual decision by negotiation [8, 9]. Although the SDM scientific community agrees on the overall structure of SDM, and efforts have been made to expand it to integrate goals of care deliberation [10] and significant others (family or friends) in the SDM process as an additional source of decision support and preference deliberation [11, 12], there is no internationally established SDM standard. Various reviews [13, 14] showed however that the SDM elements described in the literature can be summarized in six steps (Fig. 1). Probably one of the most important SDM steps is summarized as the “key message” [15] in Fig. 1, and it stresses out the importance of patient’s self-efficacy [13], their goals of care [10] or awareness of choice [14]. This step aims to explicitly convey that “decisions cannot be made based on evidence alone, it is the person who needs to decide”[15]. Respect for autonomy demands that a person should be appropriately informed that the evidence may be lacking, of poor quality or inconclusive, and the available treatment options may often manifest variations of benefits and risks for individual patients. Therefore, it is up to individuals to determine whether the benefits balance out the risks, and which uncertainties they are most willing to accept. Once the benefits and risks of all options have been discussed (Fig. 1 step 3) and the individual is not yet ready to express a preference for a treatment option, the HCP may either make a treatment recommendation or postpone the decision to a later point in time.

Shared decision making process as described by Makoul and Clayman [13]

Regardless of the treatment choice, health complications like stroke or internal bleeding may arise during or shortly after an intervention, decided upon during an SDM process. These complications could limit patients’ decision-making capacity for subsequent treatment choices. It can alter the prognosis compared to the situation discussed during an SDM process (before the intervention), without the possibility of the patient to decide regarding the goals of care and treatment options of the arized complications. To respect their individual preferences during these deteriorating health conditions, patients should be enabled to anticipate and communicate their treatment wishes for such disease situations prior to the treatment decision. ACP is a concept developed to promote patient-centered care for situations in which the person lost the decision-making capacity and cannot speak for himself or herself. It is an iterative process involving patients, their surrogates and HCPs to discuss their goals of care and treatment options in case of temporary or permanent loss of decision-making capacity [16,17,18]. This may concern unforeseeable situations, such as an accident or sudden serious illness, as well as planned situations with incapacity for decision-making during interventions and operations with general anesthesia and in case of severe complications [19, 20]. In the ACP process, patients are empowered to communicate their goals of care with regard to 1) life prolonging treatment by all means, 2) life prolonging depending on prognosis/outcomes and/or 3) palliative/supportive care. ACP aims to collect patient’s values and treatment preferences in case of future incapacity of decision making in emergencies, prolongated or permanent loss of decision making capacity, and to document them in a written plan or an advance directive. These may include distinctly formulated preferences that are situation-specific and depend on the illness progression (if an illness is already present), or in case of unwanted outcomes after an unforeseen health crisis that may happen to any person. ACP can therefore influence the current treatment decisions, however, current treatment decisions may also trigger questions about ACP.

An ACP Delphi study differentiates between five important ACP elements: (1) care consistent with patient’s goals, (2) designation of a surrogate decision-maker, (3) documentation of the surrogate decision maker, (4) discussions with surrogate and (5) accesability of the documented and recorded patient wishes [21].

Both SDM and ACP are concepts, which also support patients with moderate or high risk of complications to express their autonomy in the decision-making process for immediate and future care. Within best practice literature, current medical curricula and existing guidelines, both concepts are cited and recommend for use in usual care. Although they share the common goal of fostering person centred care and well informed choices, there is no explicit literature that combines the two concepts into one single process, nor are there any documented examples on how the two concepts are being applied.

In this paper we aim to (1) assess how SDM and ACP is being applied using the care of patients with aortic stenosis (AS) as an example, and (2) propose a model to best combine the two tools and integrate it in the care process.

To reach these aims, we looked into how SDM and ACP are being used in the care of people with aortic stenosis (AS). It is a progressive fatal disease that occurs in 0.3–0.5% of the general population, and severe AS occurs in 3–4% in people older than 75 years of age, for which an invasive treatment is advised [22]. AS can be managed either by surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), or symptoms can be managed with palliative care. As all treatment modalities come with specific benefits and risks (severe bleeding or ischemic stroke) with an elevated chance of being temporarly or even permanently unable to make autonomous decisions, current AS management guidelines recommend shared decision-making (SDM) [7] and advance care planning (ACP) [23, 24] to facilitate informed patient choices for these patients before a treatment decision. We therefore chose to conduct a systematic literature review on the use of SDM and ACP in the usual care of patients with AS. Based on this patient group we hope to be able to provide a model applicable for other cohorts in which both concepts are recommended as a standard for good care.

Methods

Systematic literature review

We conducted a systematic literature search in CINAHL, Cochrane, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, Scopus and Web of Science (see supplementary file 1 for search strategy). We included all empirical studies written in English or German, which focus on patients with AS, their surrogates and/or their healthcare professional (HCP). We searched for studies that described SDM and/or ACP or other communication interventions used to aid the decision-making process (see supplementary file 1 for inclusion criteria). The first search was performed on April 11th, 2019 and the repeated final search was performed on April 24th, 2023. Three researchers (AR, NR, DD) independently screened titles and abstracts against the above described inclusion criteria. We then assessed the full texts according to the inclusion criteria for a definitive study inclusion. Disagreements were solved by discourse and inclusion of a fourth researcher (AR, NR, DD and TK). Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) was used to decide on the trustworthiness, relevance and results of all included papers [25]. The results of each included study have been individually screened, analyzed and synthesized using MAXQDA® software. By means of thematic analysis, we have critically and systematically analyzed and synthesized the findings with the purpose of determining the status quo and distinguish between the various processes leading to a treatment decision. This hermeneutic process is required to reach the second aim of our study: to suggest an integrative model for SDM and ACP for the peri interventional situation.

SDM and ACP model

For the second purpose, the team (AR, IKR, JK and TK) built its data analysis process on the concept of empirical ethics. The process implies combining empirics (in this case the results provided by the review) with abductive reasoning (TK, JK) for the subsequent development of new understandings and concepts that may complement the ones more broadly used (AR, IKR, JK and TK) [26].

Results

Systematic literature review

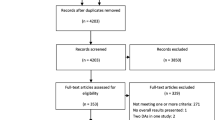

The search strategy identified 2132 individual publications including two additional studies identified through other means (hand search and reference list search) (Fig. 2). 15 studies were included in the final analysis [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] (for description of the included studies, please see supplementary file 2). Cohen’s κ was measured to determine the agreement between the two researchers (NR, DD) on 10% of the overall scope, with a substantial agreement at κ = 0.7975.

Table 1 summarizes the identified SDM steps and components described in the existing literature. From the six steps of SDM (Fig. 1), step three – information about treatment options, was most widely described and mentioned within twelve studies. Ten studies reported the means by which information was delivered (decision aid [27, 33, 34] or through HCP [28, 29, 32, 36, 37, 39, 41]) while two studies did not make any clear specifications [31, 40]. A second most widely applied SDM step was the exploration of patient wishes and concerns in the decision-making process (step 4)[27, 29, 32,33,34, 36, 37]. Description of how the decision was made was described by six studies [29, 34, 36, 38, 39, 41]. Four studies reported about patient’s goals of care regarding immediate care outcomes which can be attributed to the second step of SDM – the key message [30, 35, 38, 40].

ACP on the other hand, or its important components have not been identified as an issue of observation. The fundamental goals of care reported by some studies were related to the outcome of the particular treatment outcome (SAVR, TAVI or medication) but with no evidence of deliberation of fundamental goals of care in case of emergencies or complications during or after the intervention.

Patient wishes, concerns and preferences regarding decision-making and treatment process

Improvement of quality of life through maintaining independence, ability to perform specific activity and symptom mitigation [29,30,31,32, 35, 38, 40] as well as life prolongation [31, 32, 35, 37, 38, 40] were the most often reported patient wishes. Lifelong use of anticoagulants, risk of bleeding or blood clot, valve sound, need for reoperations [28, 34, 37], valve lifespan [32] or other risks like stroke, blood transfusion, prolonged need for ventilations and possibility of dialysis [30] were some of the main patient concerns that were reported in the included studies. Becoming a burden to the family or society was also a concern some patients expressed [38]. Further patient concerns were related to the diagnosis, intervention and its benefits, as well as whether the HCPs medical skills are sufficient to ensure a good outcome [31, 40]. Prognostic information describing the gradual increase of symptoms as well as illness severity (especially when the illness symptoms worsen) led to preferences for an intervention (TAVI) [29, 31]. Comorbidities, on the other hand, led to preferences for palliative care [30].

Low patient literacy regarding the intervention, its benefits and risks, were also reported [28], potentially indicating poor communication between the HCP and patient. Patient literacy improved with the increase of decision aids (DA) [33, 34] use as well as with an increased clinician experience in using DA [33]. The effect of DAs on decisional conflict seems to be contradictory, with some studies reporting no effect [27, 33], and another study reporting a significant effect [34]. This may be explained by the low amount of participants as well as the use of different decisional conflict measurement tools.

Patient wishes, concerns and preferences regarding support

Studies reported that many patients showed a favorable preference for engaging friends or family in the decision-making process [28, 31], which might suggest a degree of willingness to accept their suggestions or expectations. One study reported that patients either wished to involve the significant others in the decision process or exclude them and leave the decision to the HCP [36]. Some studies show that family members often strongly favored the intervention, which in turn influenced patients’ preference towards it [29,30,31]. HCPs also expressed strong preferences in favor of the intervention, with some convincing [29], recommending [31] or deciding for the patient [27, 28, 32]. Studies also reported that patients engaged themselves in the decision-making when actively encouraged by their HCPs [29, 30].

Patient engagement in the decision making process

A few studies reported that some patients expressed an explicit wish to make decisions by themselves [29] or wanted to be involved in the decision-making [28, 31, 39]. One study reported patients making treatment decisions based on their preferences as well as information regarding outcomes like anticoagulation, future interventions and recovery time [37]. Younger patients assessed themselves as being more engaged in the decision-making than the older patients [31,32,33].

Decisional conflict was mostly reported in pre-operative patients [27, 28, 31], which was lower in patients that trusted their HCPs [29, 31] or that involved their friends and family [28, 31]. Post-operative patients reported a lower decisional conflict [28, 32]. This variation can be explained by the success of the intervention, being better measurable in patients without complications, who survived the intervention. Another study reported that involvement of patients in the decision making process as well as providing enough information significantly decreased the risk of decisional conflict in patients [39]. One study comparing SAVR/TAVI patients to medical management patients observed a difference in decisional regret. 97% of the SAVR/TAVI group agreed to strongly agreed that the decision was the right one as compared to only 69% of medical management group [41].

Cognitive impairment was reported to trigger a passive position in patients during the decision-making process [29].

SDM and ACP Model

To make suggestions for improvement, we built our analysis on combining abductive reasoning with empirics (in this case the results provided by the review). This technique allows us to connect the existing gaps and build new understandings and concepts that may complement the ones more broadly used. We therefore propose a decision-making process, based on the available guidelines and recommendations and the theories on which SDM and ACP are built as well as on the results of this literature review (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 builds upon the SDM model developed by Elwyn et al. [10, 42] and on the six SDM components described by Makoul et al. [13] and Bomhof-Roordink et al. [14].

Team talk

The SDM scientific community has historically focused on a bidirectional communication process between the patient and the HCP. ACP, on the other hand, has explicitly encouraged the inclusion of significant others (family or close friends) in the decision-making process. As reported in the included studies, the patients with AS were willing to involve their loved ones in the decision-making process. The model proposes to create a team made out of important decision-makers – the patient, their significant others (family and/or friends) and HCPs. Here “HCPs” would include the entire treating team – general practitioner, cardiologist, surgeon, study nurse and whenever needed, a geriatrist and palliative care team.

The decision-making team will proceed by defining the problem that must be addressed (AS management), discussing the patient’s disease/symptom goals of care for the immediate treatment and make sure there is common understanding that the decision should be based both on evidence and patient’s own preferences and wishes (key message or choice awareness).

Option talk

At this stage, the HCPs present the necessary information and evidence regarding all available treatment options. The benefits and risks of each option (TAVI, SAVR, palliative care), including the option of “wait and see” should be discussed. The HCP should also explain the quality of the evidence and its sources, going on to differentiate between own experiences or observations and current peer-reviewed literature. This will help the patient and their significant others balance out risks against the benefits. Ideally, the HCP will use a validated decision aid to help the patient better compare the available options.

Decision talk

The decision talk between the patient, their significant other and HCPs are best made in iterative manner. At first, the concerns, preferences and expectations regarding the treatment outcomes are openly expressed by the patient, their significant other and is requested, the HCPs. If the patient is ready, they may make a decision regarding their immediate care planning – TAVI, SAVR or palliative care. They may also decide to leave or delegate decisions to their significant others. If, for example, the patient decides to choose TAVI, the entire team will then initiate an ACP team talk in case of complications. This will mark the beginning of the ACP process.

ACP Team Talk

At this stage, the decision-makers discuss how the patient wishes to be treated in case of complications that may occur (in this case after a TAVI intervention), or if their health condition deteriorates and the patient is not able to make autonomous decisions anymore. According to the existing ACP models [43], special guiding questions can be helpful to formulate preferences regarding fundamental and functional goals of care for different situations of incapacity of decision making (emergency, ICU treatment with risk for preference-sensitive outcomes, permanent incapability of decision-making etc.).

ACP option talk

Depending on the treatment risks of complications, different treatment options may be considered (resuscitation during the intervention, intensive care, etc.) All of these carry their own risks and should be discussed during the ACP option talk process. Ideally, the HCP will use a validated decision aid to help the patient better compare the available options.

ACP decision talk

During the ACP decision talk, the team should express their preferences and concerns regarding the discussed goals of care in case of complications, also making decisions and document choices regarding advance care planning.

Evidence-based care planning and advance care planning

Once the patient has decided on a care plan and an advance care plan, one could conclude that a complete evidence-based patient treatment plan and informed choice has been made. At this point, it is particularly important to document all patient care and advance care preferences in the form of informed consent and advance directives, or an equal documentation of patient’s preferences in the case of possible emergencies and complications, accessible by surgeons, cardiologists, anesthesiologists and ICU or palliative care physicians alike. After the decision has been implemented (the TAVI was performed), the patient may re-evaluate their decisions and make adjustments where needed.

Discussion

Patients with aortic stenosis may experience deterioration of their condition at any time. In addition, although therapies such as SAVR or TAVI can offer symptom relief, they can cause complications. By means of SDM and decision aids [44], patients can align their preferences to the existing treatment options (TAVI, SAVR or medication only, targeting life prolongation and/or quality of life and symptoms). SDM allows for broad information exchange based on evidence-based medicine. Patient treatment preferences can also be prediscussed for such situations with complications. This needs a systematic discussion of the fundamental goals of care in these scenarios according to the concept of ACP. ACP supports the patient to make plans regarding their treatment before the occurrence of a future sudden, prolonged or chronic incapacity of decision-making. Historically, SDM was developed to be used in prevention or acute care settings for cases with reduced medical complexity. As SDM proved its value for facilitating patient autonomy, it has been increasingly used in more complex situations which involve chronic illnesses as well as in situations in which a treatment decision might imply risky treatment complications (as in the case of patients for AS). To be able to ensure that autonomous patient treatment choices are being integrated in the treatment process in cases of decision-making incapacity, it is advisable to extend SDM into a broader process, which includes ACP.

The novelty of this paper is the practical merger of the two concepts to improve decision-making processes during care planning and advance care planning. It allows participating decision-makers to have a better understanding about the short- and long-term treatment options, as well as the patient’s short- and long-term goals of care. This approach aims at supporting patients to make better informed decisions for immediate care, as well as to better prepare for future care in case expected treatment outcomes differ from the ones expected in case of a successful intervention. This may help patients and their significant others build more accurate expectations about their treatment and recovery path, therefore helping better manage this stressful situation. Integrating SDM and ACP into one complex process may seem costly and time consuming at first, however, an interdisciplinary approach may help better manage resources to offer best support for patients while keeping costs and time needed for decision deliberation lower than if these issues had not been discussed with the patient himself/herself before the intervention [45]. Strong collaborative relationships between treating HCPs and advance practice nurses or nursing experts may help break the decision-making process in meaningful blocks managed by different experts belonging to one treating team [46]. Therefore, a patient with AS may perform the SDM process regarding the immediate care of AS together with their significant others, a cardiologist, a heart surgeon, a geriatrist and their general practitioner. The decision-making process may afterwards be continued by a cardiology nursing expert with further training in ACP to determine how the patient wants to continue their treatment in case of inability to make decisions for themselves after the intervention and to discuss preferences in case of unforeseen emergencies. At this stage, the treating HCPs may decide to not participate in the ACP decision-making process, but rather take knowledge of the patient’s advance directives, which result from the process.

Limitations

Because of the rather limited number of studies documenting the implementation of SDM and ACP in current care, this review allows us to draw conclusions with limited depth and representativeness about decision-making in severe AS patients. The ten included studies with post intervention data collection [28, 29, 32, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41] might bias the results of this review, as their sample most probably excluded patients that decided for palliative care, or were incapacitated by the intervention or were deeply unsatisfied with the treatment outcome, which might have had an impact on their willingness to continue participating in the study.

The lack of consensus on the exact content and application of SDM and ACP makes it difficult to make clear assumption regarding the use and implementation of the two concepts in the existing literature.

The integrative model described in Fig. 3 may only be used in situations in which patients can make autonomous treatment decisions. The model cannot be implemented in decision-making processes in which patients have already lost the decision-making capacity.

Solutions

Further research on the implementation of current guidelines to integrate SDM and ACP in usual care is highly recommended. For such research to be able to take place, the SDM and ACP scientific community must agree on o validated SDM and ACP standards for chronically ill or risks of treatment/intervention complications. These should be complemented with studies researching the barriers and facilitators towards better engaging patients in their own care. A longitudinal prospective cohort study detailing the implementation of SDM and ACP in patients with complicative outcomes (like severe AS patients) could better describe the exact implementation processes, its effects as well as possible barriers and facilitators. Development of decision aids which combines fundamental and disease/symptom goals of care for immediate outcomes (SDM) as well as for situations in which patients might lose their decision-making capacity (ACP) could help determine how they perform compared to decision aids that only focus on immediate outcomes (SDM). Another important field of research would involve the use of goals of care formulated for immediate outcomes (SDM) and future outcomes in case of decision making incapacity (ACP), and how they impact the decisional regret and emotional burden of surrogates or other significant others also involved in the decision-making process as compared to surrogates that only participated in goals of care deliberations for immediate outcomes (SDM).

Conclusion

SDM and ACP are similar concepts with an identical aim – to ensure that patients receive the treatment which best aligns with their preferences, values and short- and long-term goals of care. SDM mostly focuses on the short to mid-term goals of care, while ACP mostly focuses on long-term goals of care in case of hypothetical situations of reduced or limited decision-making capacity. Although both concepts can be applied separately, they must be integrated in the case of patients, whose treatment decisions might lead to loss of decision-making capacity during or shortly after an intervention.

When individuals become severely ill, patient autonomy may become very fragile and subject to various influences stemming from the patient themselves or from the outside. Illness burden, HCP or family members’ preferences are strong predictors of the patient’s final decision. An iterative process allows for each important decision-maker to share their preferences and concerns regarding the care planning and advance care planning. This would help to better structure and prioritize information while creating a trustful and respectful relationship between the participants. This may support not only patients to make autonomous decisions, but also allow for family members to best support them, and HCPs to deliver care which best complies with their patient’s values and fundamental goals of care. This ongoing support can provide the basis for enabling patient autonomy throughout the treatment process.

References

AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. Code of Medical Ethics of the American Medical Association. American Medical Association; 2016.

Good medical practice. 2021. https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/good-medical-practice. Accessed 4 May 2021.

Cassel EJ. The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198203183061104. 2010. https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJM198203183061104. Accessed 5 May 2021.

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Seventh Edition. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2013.

Childress JF, Childress MD. What does the Evolution from Informed Consent to Shared decision making teach us about Authority in Health Care? AMA J Ethics. 2020;22:423–9.

Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J, editors. CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015.

Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, Gentile F, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the management of patients with Valvular Heart Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143:e72–227.

Kasper J, Légaré F, Scheibler F, Geiger F. Turning signals into meaning–’shared decision making’ meets communication theory. Health Expect. 2012;15:3–11.

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681–92.

Elwyn G, Vermunt NPCA. Goal-based Shared Decision-Making: developing an Integrated Model. J Patient Exp. 2020;7:688–96.

Osamor PE, Grady C. Autonomy and couples’ joint decision-making in healthcare. BMC Med Ethics. 2018;19:3.

Bibas L, Peretz-Larochelle M, Adhikari NK, Goldfarb MJ, Luk A, Englesakis M, et al. Association of Surrogate decision-making interventions for critically ill adults with patient, Family, and Resource Use Outcomes. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e197229.

Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:301–12.

Bomhof-Roordink H, Gärtner FR, Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH. Key components of shared decision making models: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e031763.

Kienlin S, Nytrøen K, Stacey D, Kasper J. Ready for shared decision making: pretesting a training module for health professionals on sharing decisions with their patients. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26:610–21.

Houben CHM, Spruit MA, Groenen MTJ, Wouters EFM, Janssen DJA. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:477–89.

Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, van Delden JJ, Drickamer MA, Droger M, et al. Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e543–51.

Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JAC, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2014;28:1000–25.

Kata A, Sudore R, Finlayson E, Broering JM, Ngo S, Tang VL. Increasing Advance Care Planning through a Surgical optimization program for older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:2017–21.

Yamamoto K, Yonekura Y, Hayama J, Matsubara T, Misumi H, Nakayama K. Advance Care Planning for Intensive Care Patients during the Perioperative period: a qualitative study. SAGE Open Nurs. 2021;7:23779608211038844.

Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Lum HD, Rietjens JAC, Korfage IJ, Ritchie CS, et al. Outcomes that define successful advance Care Planning: a Delphi Panel Consensus. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:245–255e8.

Johnston DR, Zeeshan A, Caraballo BA. Aortic Stenosis. In: Levine GN, editor. Cardiology Secrets. 5th edition. Elsevier; 2018.

Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, Goldstein NE, Matlock DD, Arnold RM, et al. Decision making in Advanced Heart failure. Circulation. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e31824f2173.

Denniss DL, Denniss AR. Advance Care Planning in Cardiology. Heart Lung and Circulation. 2017;26:643–4.

CASP - Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP - Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. https://casp-uk.net/. Accessed 28 Apr 2020.

Christen M, van Schaik C, Fischer J, Huppenbauer M, Tanner C, editors. Empirically informed Ethics: morality between facts and norms. Springer International Publishing; 2014.

Korteland NM, Ahmed Y, Koolbergen DR, Brouwer M, de Heer F, Kluin J et al. Does the use of a decision aid improve decision making in Prosthetic Heart Valve Selection? A Multicenter Randomized Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10.

Korteland NM, Bras FJ, van Hout FMA, Kluin J, Klautz RJM, Bogers AJJC, et al. Prosthetic aortic valve selection: current patient experience, preferences and knowledge. Open Heart. 2015;2:e000237.

Skaar E, Ranhoff AH, Nordrehaug JE, Forman DE, Schaufel MA. Conditions for autonomous choice: a qualitative study of older adults’ experience of decision-making in TAVR. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14:42–8.

Coylewright M, Palmer R, O’Neill ES, Robb JF, Fried TR. Patient-defined goals for the treatment of severe aortic stenosis: a qualitative analysis. Health Expect. 2016;19:1036–43.

Olsson K, Näslund U, Nilsson J, Hörnsten Ã. Patients’ decision making about undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation for severe aortic stenosis. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;31:523–8.

Schmied W, Barnick S, Heimann D, Schäfers H-J, Köllner V. Lebensqualität oder Lebenserwartung? Kriterien und Informationsquellen für die Entscheidungsfindung bei Patienten im Vorfeld von Aortenklappenoperationen. Z für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychother. 2015;61:224–37.

Coylewright M, O’Neill E, Sherman A, Gerling M, Adam K, Xu K, et al. The learning curve for Shared decision-making in symptomatic aortic stenosis. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:442.

Anaya J, Moonsamy P, Sepucha KR, Axtell AL, Ivan S, Milford CE, et al. Pilot study of a patient decision aid for Valve Choices in Surgical aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;108:730–6.

Beishuizen SJE, Festen S, van der Werf HW, de Graeff P, van Munster BC. Was it worth it? Benefits of transcatheter aortic valve implantation from a patient’s perspective. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:2605–11.

Ingle MP, Carroll AM, Matlock DD, Gama KD, Valle JA, Allen LA, et al. Decision support needs for patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2022;65:589–603.

Picou K, Heard DG, Shah PB, Arnold SV. Exploring experiences associated with aortic stenosis diagnosis, treatment and life impact among middle-aged and older adults. J Am Association Nurse Practitioners. 2022;34:748.

Sugiura K, Kohno T, Hayashida K, Fujisawa D, Kitakata H, Nakano N, et al. Elderly aortic stenosis patients’ perspectives on treatment goals in transcatheter aortic valvular replacement. ESC Heart Failure. 2022;9:2695–702.

Bryssinck L, De Vlieger S, François K, Bové T. Post hoc patient satisfaction with the choice of valve prosthesis for aortic valve replacement: results of a single-centre survey. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2021;33:210–7.

Col NF, Otero D, Lindman BR, Horne A, Levack MM, Ngo L, et al. What matters most to patients with severe aortic stenosis when choosing treatment? Framing the conversation for shared decision making. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0270209.

Dharmarajan K, Foster J, Coylewright M, Green P, Vavalle JP, Faheem O, et al. The medically managed patient with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis in the TAVR era: patient characteristics, reasons for medical management, and quality of shared decision making at heart valve treatment centers. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0175926.

Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, Aarts J, Barr PJ, Berger Z et al. A three-talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation process. BMJ. 2017;359.

Karzig-Roduner I, Otto-Achenbach T, Meissner G, Loupatatzis B, Arnold S, Weber A et al. Die Patientenverfügung «plus». In: Wie ich behandelt werden will: Advance Care Planning. 1st edition. Rffer&Rub Sachbuchverlag; 2020.

Treatment Options for Severe Aortic Stenosis. – Colorado Program for Patient Centered Decisions. https://patientdecisionaid.org/aortic-stenosis/. Accessed 1 Apr 2022.

der Klingler C. Schmitten J, Marckmann G. Does facilitated Advance Care Planning reduce the costs of care near the end of life? Systematic review and ethical considerations. Palliat Med. 2016;30:423–33.

Villalobos M, Siegle A, Hagelskamp L, Handtke V, Jung C, Krug K, et al. HeiMeKOM (Heidelberg Milestones Communication): development of an interprofessional intervention for improvement of communication in patients with limited prognosis. ZEFQ. 2019;147:28–33.

Funding

This manuscript is part of the project “ACP and SDM in patients with severe aortic stenosis” funded by the Swiss Academy of Medical Science. The Project was funded with 150’000 swiss francs for a period of 3 years including salaries, study materials, compensations.

Agnowledgement: Frank Scherff for his support in the cardiac disease management. Theodore Otto for her support in conceptualizing ACP and SDM into one model.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AR – conception, design of the work, analysis, interpretation of data, drafted the work, IKR – conception, interpretation of data, drafted the work. JK – conception, interpretation of data, NR – acquisition of data, DD – acquisition of data, TK – conception, design of the work, interpretation of data, drafted the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosca, A., Karzig-Roduner, I., Kasper, J. et al. Shared decision making and advance care planning: a systematic literature review and novel decision-making model. BMC Med Ethics 24, 64 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-023-00944-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-023-00944-7