Abstract

Background

When including participants with dementia in research, various ethical issues arise. At present, there are only a few existing dementia-specific research guidelines (Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use in Clinical investigation of medicines for the treatment Alzheimer’s disease (Internet). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/clinical-investigation-medicines-treatment-alzheimers-disease; Food and Drug Administration, Early Alzheimer’s Disease: Developing Drugs for Treatment Guidance for Industry [Internet]. http://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/alzheimers-disease-developing-drugs-treatment-guidance-industy), necessitating a more systematic and comprehensive approach to this topic to help researchers and stakeholders address dementia-specific ethical issues in research. A systematic literature review provides information on the ethical issues in dementia-related research and might therefore serve as a basis to improve the ethical conduct of this research. This systematic review aims to provide a broad and unbiased overview of ethical issues in dementia research by reviewing, analysing, and coding the latest literature on the topic.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review in PubMed and Google Scholar (publications in English between 2007 and 2020, no restrictions on the type of publication) of literature on research ethics in dementia research. Ethical issues in research were identified by qualitative text analysis and normative analysis.

Results

The literature review retrieved 110 references that together mentioned 105 ethical issues in dementia research. This set of ethical issues was structured into a matrix based on the eight major principles from a pre-existing framework on biomedical ethics (Emanuel et al. An Ethical Framework for Biomedical Research. in The Oxford textbook of clinical research ethics, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2008). Consequently, subcategories were created and further categorized into dementia stages and study phases.

Conclusions

The systematically derived matrix helps raise awareness and understanding of the complex topic of ethical issues in dementia research. The matrix can be used as a basis for researchers, policy makers and other stakeholders when planning, conducting and monitoring research, making decisions on the legal background of the topic, and creating research practice guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dementia prevalence rates are estimated to quadruple by 2050 [1, 2]. Though such forecasts must be interpreted carefully, the global community is likely to face several challenges concerning the individual and familial burdens, societal and political consequences, and economic impact of dementia. With the growing size of the population with dementia, the costs of care are expected to increase in the near future [1].

The need for research on risk factors [2], palliative care, and reducing individual psychological burden is therefore of global importance. Research conducted with participants living with dementia raises important ethical questions, such as how to protect cognitively impaired persons against exploitation, how to design informed consent (IC) procedures with proxies, how to disclose risk-factors for dementia given the lack of evidence for their reliability, and how to apply risk–benefit considerations in such cases [3].

Out of fear of not being able to fulfil the ethical obligations required when conducting research with incapacitated persons, some might suggest the overall exclusion of cognitively impaired persons, or even of all individuals affected by dementia, from research. This caution may lead to the abandonment of meaningful research on dementia and would exclude dementia research from medical progress, leaving affected persons and their relatives orphaned.

Several guidelines [4, 5] provide some orientation as to what should be considered to ensure that research on humans is ethical. These guidelines cover the entire research process from planning, conducting, and monitoring the trial to post-trial. Furthermore, they claim specific protection for vulnerable groups and individuals but are not meant to provide details on what that means for dementia research or other patient groups. Many authors have discussed the ethical challenges of dementia research [3, 6,7,8, 12, 14,15,16]. These publications are characterized by a rather narrow focus on certain issues, e.g., on alternatives for obtaining IC [3, 6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13] or genetic testing [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Some even use a combination of a systematic and a narrative review approach, with the emphasis on identifying differences in the ways ethical issues are addressed [21]; however, a review of the full spectrum of ethical issues in dementia research is still missing in the current literature.

In our systematic review, we therefore aimed to identify the full and unbiased spectrum of research on ethical issues in dementia as discussed in the literature.

Methods

Literature search and selection

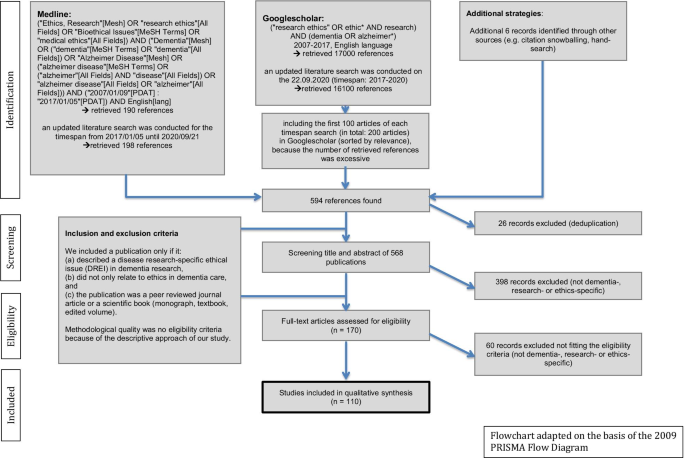

Three strategies were applied to the literature search: PubMed (database), Google scholar and hand searching methods. We included a publication only if it: (a) described a disease research-specific ethical issue (DREI) in dementia research, (b) did not only relate to ethics in dementia care, and (c) the publication was a peer reviewed journal article or a scientific book (monograph, textbook, edited volume). Methodological quality was no eligibility criteria because of the descriptive approach of our study.

The Flowchart (Fig. 1) presents further details on the search algorithm and the eligibility criteria. This approach has already been applied before and can be read in detail elsewhere [22]. For reference management, we used the programme “Zotero”.

Definition and typology of dementia research-specific ethical issues (DREIs)

For the definition of DREI, we referred to the ethical theory of principlism. Emanuel et al. suggest eight principles that make clinical research ethical: respect for participants, independent review, fair participant selection/recruiting, favourable risk–benefit ratio, social value, scientific validity, collaborative partnership and IC [4]. These principles represent guiding norms that must be followed in a particular case unless there is a conflict with another obligation that is of equal or greater weight, e.g., alternatives to obtaining IC in special groups or situations. These principles provide only general ethical orientations that require further detail to give guidance in concrete cases. Thus, when applied, the principles must be specified and—if they conflict—balanced against one another.

There are two types of ethical issues that could arise: (a) inadequate consideration of one or more principles (e.g., “risk of insufficiently informing IRBs [institutional review boards] about adequate steps taken to fulfil the ethical obligations of dementia research”) or (b) conflicts between two or more principles (e.g., “challenge of balancing divergent statements in ARD [advance research directive] against current dementia patient wishes or proxy decisions (now vs. then)”). The terms "risk" (a) and "challenge" (b) used in the following refer to this conceptual consideration.

Analysis and synthesis of DREIs

For analysis, we used thematic content analysis [23] for all 110 included references. To identify and clarify potential ambiguities during content analysis as early as possible a first purposively sampled cluster of references (n = 10) was coded by two reviewers (TG, HK) independently. Another sample of detailed references (n = 9) was coded by one reviewer (TG) only. To capture as many ethical issues as possible this first cluster purposively included more detailed and comprehensive publications. The identified issues were then compared and grouped into the eight principles framework [4] in a consensus process using a programme for qualitative data analysis (“MAXQDA”). Because the consensus process revealed sufficient clarity for how to deal with ambiguous codings the remaining references (n = 45) were randomly split in half and analysed by one author (HK or TG) only. We updated the search in September 2020 and included another sample of 46 studies. These studies were coded by one author (TG). If further ambiguities during coding occurred they were discussed and clarified in the team.

For synthesis, we used a mixed deductive-inductive approach that takes into account the eight principles and the descriptions from the primary literature. We introduced subcategories if we found it reasonable to do so (for example if the number of DREIs was high). Finally, we used dementia stage and study phase to further categorize the identified issues (see Table 1). While we started with the established eight principles for clinical research ethics as a coding framework, our coding procedure was open for DREIs which could not be grouped under one of the eight principles.

Results

References and journals

The literature search in PubMed and Google Scholar revealed a total set of 594 references, 110 of which were ultimately included in the analysis, published between 2007 and 2020 in 64 different journals. For more details, see the flowchart (Fig. 1).

Spectrum of dementia research ethical issues (DREIs)

The analysis of the 110 references revealed 105 DREIs. All identified issues could be grouped under one of the eight principles for ethical research, some having far more DREIs than others. In detail, “respect for participants” (n = 11 DREIs), “independent review” (n = 3), “fair participant selection/recruiting” (n = 5), “favourable risk–benefit ratio” (n = 16, 3 subcategories), “social value” (n = 2), “scientific validity” (n = 20, 5 subcategories), “collaborative partnership” (n = 5) and “informed consent (IC)” (n = 43, 12 subcategories). In the course of data analysis, we subsequently found fewer new codes, and the last 10 analysed papers raised no new issues. Thus, we appear to have achieved thematic saturation for the spectrum at least for the level of major groups and first-level subgroups. We updated the search in September 2020 which lead to the analysis of 46 references from the years 2017 until 2020. During the process of literature analysis, only one new subcategory was found in a paper from 2018 [24], hereafter no new sub-categories have been identified (for the years of 2019 and 2020).

All identified DREIs and subcategories are presented in Table 1. This table also contains the categorization according to the dementia stage (based on the NIA-AA-2018-Framework) [25] and the phase of the research for each issue, symbolized by superscript numbers or characters. Additionally, the 105 DREIs are presented in separate tables for each category of dementia stage (Additional file 1) and the phase of the research (Additional file 2). A full list of the found issues together with the accompanying original text examples as well as the list of all references that were analysed during our systematic review are available in Additional file 3: Table S3. The above listed tables are available at the supplemental data.

We used the nomenclature of the NIA-AA-2018-framework (“cognitively impaired”, “mild cognitive impairment (MCI)” and “dementia”) [25] for the first three categories in our dementia stages categorization. Most DREIs were related to more than one dementia stage (category IV, n = 60, Table 1). DREIs related to “cognitively unimpaired” (category I, n = 7) centre around the principle of favourable risk–benefit ratio, especially dealing with the sub-categories “determining risk adequately” and “considering risk adequately”, and the principle of respect for participants. No issues were found to fit “mild cognitive impairment” exclusively (category II), where people with dementia are not yet incapacitated. In category III = dementia (n = 11), issues mostly referred to “IC”, especially addressing the sub-category “proxy consent”. Finally, 27 DREIs could not be classified in that split spectrum.

Concerning the categorization due to study phase, we used a timeline approach in naming the different study phases (I = recruiting/pre-trial, II = conduction phase, III = post-trial, IV = general). For DREIs related to specific study phases, again, most DREIs were found to be of overarching relevance (category D, n = 45). In the recruiting/pre-trial phase, DREIs arise within “independent review”, “fair participant selection/recruiting”, “scientific validity”, and “informed consent” (category A, n = 32). While conducting the study (category B, n = 9), DREIs are related to “drop-outs” that endanger scientific validity and the “ongoing assessment” within the principle of informed consent. The post-trial phase is mostly concerned with the principle of respect for participants, communicating the results to the participants and the scientific community (“poor reporting quality”) and adequate follow-up of the volunteers (category C, n = 6). Thirteen issues could not be classified under the topic of study phase.

Specification of general principles for ethical dementia research

All principles for ethical research [4] were specified in the analysed literature. The references to general principles, such as “IC”, are rather implicit; however, authors elaborate on how the characteristics of dementia lead to specific ethical challenges, e.g., “However, a special ethical issue with regard to longitudinal studies that end in participants’ death is that participants are competent when first recruited, but have a significant likelihood of becoming incompetent while they are study subjects. […] [T]he gradual loss of the capacity to consent […] creates challenges for informed consent, the ethical bedrock of research with human subjects. […][Here], it may make sense to re-evaluate consent capacity […] at several intervals during the study" [6].

From this statement, the following DREI was paraphrased: “Risk that IC at the beginning of a dementia study alone is insufficient because of cognitive decline of participants”. This DREI is of general relevance for all dementia stages but has particular relevance to the study phase “recruiting/pre-trial”. The full spectrum of issues, including original text examples and all references, is presented in the online supplement (see Additional file 3).

Issues which were mentioned the most, are, for example, “Risk of excluding relevant subgroups, e.g. inhabitants of nursing homes, those lacking a proxy/spouse or patients with other psychiatric diseases, from dementia research” (n = 25 papers) and “Risk of excluding participants from research due to lack of capacity to consent” (n = 23). Examples of rarely mentioned DREI are “Risk that dementia patients experiencing stigmatization will lead to low follow-up rates or study withdrawal” (n = 1), “Risk of therapeutic misconception being higher in participants with MCI or mild dementia” (n = 1) and “Risk of RECs [research ethics committees] weighing opinions of physicians (protecting the participant) over patients’ willingness to participate and over nurse counsellors’ opinions” (n = 1).

Several DREIs were only addressed in an implicit manner; for example, “Risk that varying international regulations are a burden for international dementia research” is based on the following quotation: “However, only in Germany and Italy is the system of proxy determined by the courts—a procedure which is not necessarily required for the recognition of a proxy in other member states” [26].

Discussion

This systematic literature review identified and synthesized the full spectrum of 105 ethical issues in dementia research (DREIs) based on 110 references published between 2007 and 2020 in 64 different journals.

Many ethical issues involved “IC” (n = 11) in incapacitated participants and “risk-information disclosure” (n = 8). However, this review shows that there are many more DREIs to consider when planning, reviewing, conducting, or monitoring research with this vulnerable group. We assume that the results will be of interest to different groups—clinical experts, researchers, policy makers, REC-members, lawyers, patient-organization representatives or even affected persons themselves—and that the different stakeholders will read and use the results differently.

Our review lists several ethical issues grouped under eight broadly established ethical principles for clinical research. These principles and the principlism approach in general are correlative to basic human rights [26]. The eight principles are not focused on capacity-based approaches but include approaches to express the right to participate in research via, for examples, advance directives. We would therefore argue, in line with many other ethical analyses based on a principlism approach, that human rights related ethical issues in dementia research are captured directly and indirectly by the many ethical issues addressed in our list of issues. The same applies to other overarching normative concepts such as “avoiding exploitation”. No specified ethical issue in our list mentions the risk of exploitation directly but more or less all specific ethical issues address this risk indirectly. Likewise, the wording “human rights” did not appear explicitly in the literature we analyzed.

Those looking for support or guidance on how to seek ethically appropriate dementia research might prefer detailed descriptions of very specific challenges. Articles such as “Seeking Assent and Respecting Dissent in Dementia Research” by Black et al. [9] serve this purpose. However, these publications often focus on particular aspects and do not aim to provide a detailed and systematic overview. Further, one also has to do thorough searching and read a large volume of material (we screened n = 594 and finally included n = 110 references) to be familiar with all the aspects discussed in the literature. In contrast to literature addressing very specific DREIs, there are also broad, theoretical frameworks for research ethics, such as that of Emanuel et al. [4]. However, if capacity building for ethics in dementia research is primarily informed by such general frameworks, it might overlook issues that only become apparent when specifying practice-related tasks. Our review is intended to bridge detailed specifications with a comprehensive and structured presentation of the DREIs at stake.

We illustrate the bridging character of our study by comparing one benchmark for the IC principle originating from Emanuel et al.’s framework [4] with one issue on our spectrum grouped under “IC” in the subcategory “proxy consent”. The benchmark is “Are there appropriate plans in place for obtaining permission from legally authorized representatives for individuals unable to consent for themselves?” [4]. A researcher with a specific trial in mind would, in order to conduct morally sound research, perhaps refer to that benchmark in a case where they plans to start a trial on incapacitated patients suffering from dementia. This person would then fulfil that benchmark by making it possible for legal representatives of the patients to fill out the IC document in place of the incapacitated participant. Thus, they would fulfil the benchmark and might not think about more specific ethical problems that might arise when one looks into the literature describing DREI. One such example is this quote stemming from an article on dementia research ethics: “Proxy consent, already an issue of debate in traditional research, was considered more problematic in genetic research, where children share the same genetic traits as their parents. On the one hand, this might be a motivation for the affected parent to participate in a research study to help their children. On the other hand, it was questioned that to what extent children still are able to make a decision in the best interest of their parents because they have an interest themselves. The more genetic research will be carried out, the higher the chance on a disease modifying or preventive therapy for them and their children” [14].

In that case, and if the researcher had a plan to conduct research in this field of genetic dementia research, the simple fulfilment of the abovementioned benchmark would be insufficient for the goal of morally acceptable research. The mentioned quotation informed the creation of the DREI “Risk of not considering that proxies have major self interest in dementia research, e.g., because they have same genetic traits, which could influence their proxy decision, and their manipulative behaviour may be difficult to detect”.

As we compared topics between both rounds of the literature analysing process, we noticed, that some topics were newly introduced in the scientific literature, in particular “deep brain stimulation” issues in dementia research. Other categories or sub-categories like “social value”, “qualified personnel” and “informed consent document” were not further discussed in scientific literature.

In addition, we found more and more text examples for issues which before the year of 2017 were only mentioned once, e.g. “Risk of over diagnosis in asymptomatic persons, if the diagnosis is derived from the risk marker status, since their corresponding validity regarding the occurrence and course of a disease is (still) limited”, which now was mentioned in six papers.

Also, in the course of the analysis of the studies between 2017 and 2020 we found 22 new issues, among them 17 issues which were only mentioned by one paper showing the rapid emergence of new issues in the dementia research ethics field.

Capturing this full spectrum of DREIs can serve multiple purposes. First, it can raise awareness of the ethical issues arising in the context of dementia research, highlighting issues that may be underrepresented in the published literature through the side-by-side presentation in our matrix. Second, it can serve as the basis for information or training materials for researchers and caregivers. Third, it can form the basis for discussions on the importance and/or relevance of the different ethical issues. Fourth, because our spectrum does not rank the difficult DREIs in order of importance, third parties can use it as a basis for exactly that purpose. Fifth, developers of specific research guidelines or policy papers may use this spectrum as an entry point to that topic.

At this point, it is important to state that our spectrum remains strictly descriptive. The qualitative and normative interpretation is therefore left to others, e.g., researchers, policy-makers, patient organizations, funding partners and the community as a whole. Those interpretations could further help in developing stakeholder-oriented guidelines for conducting ethically sound research in dementia. The list of ethical issues as presented in this paper, however, cannot directly serve as a checklist for review purposes. More conceptual work is needed to translate the in-depth results of this systematic review into effective and efficient normative or procedural guidance. Finally, existing guidelines, policy papers or new research articles on the topic of DREIs can be screened for completeness [27].

To make the results of the review more concise and accessible, we prepared overviews sorted by stage and phase (available as an online supplement). This is particularly suitable for readers who have a certain focus, e.g., because they are currently planning a study with people in an early stage of dementia (see Additional file 1) or are looking for an overview of DREIs in the phase of conducting the study (see Additional file 2). These tables show that ethical issues are situation-sensitive, e.g., certain questions on informed consent only arise at a later stage of the disease, while questions of reporting the status of risk factors are only relevant in early stage (pre-symptomatic) patients.

One limitation of this systematic review is that the search was limited to PubMed and Google Scholar. We do not consider this an overly disadvantageous factor and consider the approach to be appropriate for the following reasons: First, our search resulted in the identification of literature from different fields, not only from the bioethics and medicine field but also spanning nursing research [28, 29], nursing ethics [30, 31], a narrative review [3] and even one systematic review [21]. This systematic review by West et al. covered mostly literature concerning IC, advance directives and the role of proxies or surrogates. Second, thematic saturation for the first-level categories was achieved after analysing 54 of the 64 papers that were included after the first literature search in these two data sources. For the updated literature search, which only found one new first-level category, thematic saturation was achieved after analysing 25 of the 46 papers. Third, former systematic reviews [32, 33] in the bioethics field, which based their research on additional databanks such as EMBASE, CINAHL or Euroethics, found few additional references. Another limitation is that we only reviewed the literature from the last 14 years. However, we included two (systematic) reviews, which included literature dating back to 1982 [3] and back to 1995 [21]. We further assume that an important ethical issue that was mentioned 15 years ago and that is still relevant nowadays would be addressed in some more recent references again.

Further, we only included references in the English language. Some culturally sensitive DREI might be preferably discussed in the respective language, and our review might have missed those discussions. Last but not least, we only included peer-reviewed literature and thus did not consider grey literature such as guidelines from advocacy organizations involved with dementia research [34, 35]. As a future project, we aim to employ the results of our review to analyse whether and how guidelines for dementia research mention the identified issues. For a similar approach see the results of a systematic review of ethical issues in dementia care [22] that was followed-up by a content analysis of clinical practice guidelines for dementia care [27].

The authors of this review have different scientific backgrounds: medicine/psychiatry, physiotherapy, public health, ethics and philosophy. However, all authors are currently involved neither in clinical research nor in health care for people with dementia. However, we do not consider this to be a weakness of the review, as we have included these perspectives in the literature considered, e.g., expert opinions [9, 10, 14, 36,37,38,39], views of patients, caregivers and proxies [11, 28, 40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49], papers focusing on legal and ethical guidelines [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57], and the point of view of lay persons [13]. Our review found no papers on the opinions and views of relatives of people living with dementia. This might indicate the need for further research in that field.

Conclusions

This study has successfully shown that a systematic literature review leads to a wider spectrum of DREIs (n = 105) than other papers on the subject. The identified issues are specifications of eight general ethical principles for clinical research and could be categorized according to the dementia stage and study phase. Therefore, the spectrum can be used to raise awareness about the complexity of ethics in this field and can support different stakeholders in the implementation of ethically appropriate dementia research.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DREI(s):

-

Dementia research-specific ethical issue(s)

- IC:

-

Informed consent

- IRB(s):

-

Institutional review board(s)

- ARD:

-

Advanced research directives

- TG:

-

Tim Götzelmann

- HK:

-

Hannes Kahrass

- MCI:

-

Mild cognitive impairment

- REC(s):

-

Research ethics committee(s)

- DS:

-

Daniel Strech

- RCT(s):

-

Randomized controlled trial(s)

- EU:

-

European union

- PET-CT:

-

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

References

Wimo A, Jönsson L, Bond J, Prince M, Winblad B, International AD. The worldwide economic impact of dementia 2010. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):1–11.

Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):63–75.

Johnson RA, Karlawish J. A review of ethical issues in dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(10):1635–47.

Emanuel EJ, Grady CC, Crouch RA, Lie RK, Miller FG, Wendler DD. An Ethical Framework for Biomedical Research. In: The Oxford textbook of clinical research ethics. Oxford University Press; 2008. p. 123–35.

WMA - The World Medical Association-WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects [Internet]. [Cited 2019 Mar 19]. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/.

Davis DS. Ethical issues in Alzheimer’s disease research involving human subjects. J Med Ethics. 2017; medethics—2016.

Sherratt C, Soteriou T, Evans S. Ethical issues in social research involving people with dementia. Dementia. 2007;6(4):463–79.

van der Vorm A, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, Kehoe PG, Rikkert MGMO, van Leeuwen E, Dekkers WJM. Ethical aspects of research into Alzheimer disease. A European Delphi Study focused on genetic and non-genetic research. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(2):140–4.

Black BS, Rabins PV, Sugarman J, Karlawish JH. Seeking assent and respecting dissent in dementia research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(1):77–85.

Dubois M-F, Bravo G, Graham J, Wildeman S, Cohen C, Painter K, et al. Comfort with proxy consent to research involving decisionally impaired older adults: do type of proxy and risk–benefit profile matter? Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(09):1479–88.

Karlawish J, Kim SYH, Knopman D, van Dyck CH, James BD, Marson D. The views of alzheimer disease patients and their study partners on proxy consent for clinical trial enrollment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(3):240–7.

Kim SYH. The ethics of informed consent in Alzheimer disease research. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(7):410–4.

Kim SYH, Kim HM, Knopman DS, De Vries R, Damschroder L, Appelbaum PS. Effect of public deliberation on attitudes toward surrogate consent for dementia research.—PubMed—NCBI [Internet]. [Cited 2017 Jan 4]. Available from: https://n.neurology.org/content/77/24/2097.short.

Olde Rikkert MG, van der Vorm A, Burns A, Dekkers W, Robert P, Sartorius N, et al. Consensus statement on genetic research in dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;23(3):262–6.

SYH Kim, J Karlawish, BE Berkman. Ethics of genetic and biomarker test disclosures in neurodegenerative disease prevention trials.—PubMed—NCBI [Internet]. [Cited 2017 Jan 4]. Available from: https://n.neurology.org/content/84/14/1488.short.

Arribas-Ayllon M. The ethics of disclosing genetic diagnosis for Alzheimer’s disease: do we need a new paradigm? Br Med Bull. 2011;100(1):7–21.

Chao S, Roberts JS, Marteau TM, Silliman R, Cupples LA, Green RC. Health behavior changes after genetic risk assessment for Alzheimer disease: the REVEAL study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(1):94–7.

Christensen KD, Roberts JS, Uhlmann WR, Green RC. Changes to perceptions of the pros and cons of genetic susceptibility testing after APOE genotyping for Alzheimer disease risk. Genet Med. 2011;13(5):409–14.

Green RC, Roberts JS, Cupples LA, Relkin NR, Whitehouse PJ, Brown T, et al. Disclosure of APOE genotype for risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(3):245–54.

Salmon D, Lineweaver T, Bondi M, Galasko D. Knowledge of APOE genotype affects subjective and objective memory performance in healthy older adults. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2012;8(4):P123–4.

West E, Stuckelberger A, Pautex S, Staaks J, Gysels M. Operationalising ethical challenges in dementia research—a systematic review of current evidence. Age Ageing. 2017;1–10.

Strech D, Mertz M, Knuppel H, Neitzke G, Schmidhuber M. The full spectrum of ethical issues in dementia care: systematic qualitative review. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(6):400–6.

Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. Companion Qual Res. 2004;1:159–76.

Thorogood A, Mäki-Petäjä-Leinonen A, Brodaty H, Dalpé G, Gastmans C, Gauthier S, et al. Consent recommendations for research and international data sharing involving persons with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(10):1334–43.

Jack Cr, Da B, K B, Mc C, B D, Sb H, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease [Internet]. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2018 [cited 2020 Sep 24]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29653606/.

Gainotti S, Imperatori SF, Spila-Alegiani S, Maggiore L, Galeotti F, Vanacore N, et al. How are the interests of incapacitated research participants protected through legislation? An Italian study on legal agency for dementia patients. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6):e11150.

Knüppel H, Mertz M, Schmidhuber M, Neitzke G, Strech D. Inclusion of ethical issues in dementia guidelines: a thematic text analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(8):e1001498.

Hanson LC, Gilliam R, Lee TJ. Successful clinical trial research in nursing homes: the improving decision-making study. Clin Trials Lond Engl. 2010;7(6):735–43.

Garand L, Lingler JH, Conner KO, Dew MA. Diagnostic labels, stigma, and participation in research related to dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2009;2(2):112–21.

Heggestad AKT, Nortvedt P, Slettebø Ashild. The importance of moral sensitivity when including persons with dementia in qualitative research. Nurs Ethics. 2012;0969733012455564.

Slaughter S, Cole D, Jennings E, Reimer MA. Consent and assent to participate in research from people with dementia. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14(1):27–40.

Sofaer N, Strech D. Reasons why post-trial access to trial drugs should, or need not be ensured to research participants: a systematic review. Public Health Ethics. 2011;4(2):160–84.

Strech D, Persad G, Marckmann G, Danis M. Are physicians willing to ration health care? Conflicting findings in a systematic review of survey research. Health Policy. 2009;90(2):113–24.

Europe A. Overcoming ethical challenges affecting the involvement of people with dementia in research: recognising diversity and promoting inclusive research. Luxemb Alzheimer Eur. 2019.

Alzheimer E. Alzheimer Europe Report: The ethics of dementia research: Alzheimer Europe; 2011. 2011.

Schicktanz S, Schweda M, Ballenger JF, Fox PJ, Halpern J, Kramer JH, et al. Before it is too late: professional responsibilities in late-onset Alzheimer’s research and pre-symptomatic prediction. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:921.

Molinuevo JL, Cami J, Carné X, Carrillo MC, Georges J, Isaac MB, et al. Ethical challenges in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease observational studies and trials: Results of the Barcelona summit. Alzheimers Dement [Internet]. 2016 Mar [cited 2016 Apr 21]; Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1552526016000765.

Harkins K, Sankar P, Sperling R, Grill JD, Green RC, Johnson KA, et al. Development of a process to disclose amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal older adult research participants. Alzheimers Res Ther [Internet]. 2015 Dec [cited 2017 Jan 6];7(1). Available from: http://alzres.com/content/7/1/26.

Werner P, S S. Practical and Ethical Aspects of Advance Research Directives for Research on Healthy Aging: German and Israeli Professionals’ Perspectives [Internet]. Frontiers in medicine. 2018 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29675415/.

Cary MS, Rubright JD, Grill JD, Karlawish J. Why are spousal caregivers more prevalent than nonspousal caregivers as study partners in AD dementia clinical trials? Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2015;29(1):70–4.

Hellström I, Nolan M, Nordenfelt L, Lundh U. Ethical and Methodological Issues in Interviewing Persons With Dementia. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14(5):608–19.

Overton E, Appelbaum PS, Fisher SR, Dohan D, Roberts LW, Dunn LB. Alternative decision-makers’ perspectives on assent and dissent for dementia research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):346–54.

Grill Jd, Cg C, K H, J K. Reactions to learning a “not elevated” amyloid PET result in a preclinical Alzheimer’s disease trial [Internet]. Alzheimer’s research & therapy. 2018 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30579361/.

Hosie A, S K, N R, I G, D P, C S, et al. Older Persons’ and Their Caregivers’ Perspectives and Experiences of Research Participation With Impaired Decision-Making Capacity: A Scoping Review [Internet]. The Gerontologist. 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32866239/.

Jongsma K, J P, S S, K R. Motivations for people with cognitive impairment to complete an advance research directive—a qualitative interview study [Internet]. BMC Psychiatry. 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32641010/.

Mann J, Hung L. Co-research with people living with dementia for change. Action Res. 2019;17(4):573–90.

Morbey H, Harding AJ, Swarbrick C, Ahmed F, Elvish R, Keady J, et al. Involving people living with dementia in research: an accessible modified Delphi survey for core outcome set development. Trials. 2019;20(1):1–10.

Ries N, E M, R S-F. Planning Ahead for Dementia Research Participation: Insights from a Survey of Older Australians and Implications for Ethics, Law and Practice [Internet]. Journal of bioethical inquiry. 2019 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31297689/.

Robillard JM, Feng TL. When patient engagement and research ethics collide: lessons from a dementia forum. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;59(1):1–10.

Jongsma K, Bos W, van de Vathorst S. Morally relevant similarities and differences between children and dementia patients as research subjects: representation in legal documents and ethical guidelines: children and dementia patients as research subjects. Bioethics. 2015;29(9):662–70.

Alpinar-Sencan Z, S S. Addressing ethical challenges of disclosure in dementia prediction: limitations of current guidelines and suggestions to proceed [Internet]. BMC Medical Ethics. 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32393330/.

Fletcher JR, Lee K, Snowden S. Uncertainties when applying the mental capacity act in dementia research: a call for researcher experiences. Ethics Soc Welf. 2019;13(2):183–97.

Gove D, Diaz-Ponce A, Georges J, Moniz-Cook E, Mountain G, Chattat R, et al. Alzheimer Europe’s position on involving people with dementia in research through PPI (patient and public involvement). Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(6):723–9.

Ries NM, Thompson KA, Lowe M. Including people with dementia in research: an analysis of Australian ethical and legal rules and recommendations for reform. J Bioethical Inq. 2017;14(3):359–74.

Thorogood A, Dalpe G, McLauchlan D, Knoppers B. Canadian consent and capacity regulation: undermining dementia research and human rights. McGill J Law Health. 2018;12:67.

Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Clinical investigation of medicines for the treatment Alzheimer’s disease [Internet]. European Medicines Agency. 2018 [cited 2019 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/clinical-investigation-medicines-treatment-alzheimers-disease.

Food and Drug Administration. Early Alzheimer’s Disease: Developing Drugs for Treatment Guidance for Industy [Internet]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2019 [cited 2019 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/alzheimers-disease-developing-drugs-treatment-guidance-industy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our special gratitude to Marcel Mertz for his critical review of the categorization and paraphrasing of the issues. His expertise was used to confirm the validity of the final spectrum.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TG had a major role in the acquisition of data, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript for intellectual content. DS had a major role in the design and conceptualization of the study and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. HK analysed the data and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Table S1

: An overview of the 105 DREIs assigned to dementia stages.

Additional file 2. Table S2

: An overview of the 105 DREIs assigned to study phases.

Additional file 3. Table S3

: All principles, issues and text examples in one table.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Götzelmann, T.G., Strech, D. & Kahrass, H. The full spectrum of ethical issues in dementia research: findings of a systematic qualitative review. BMC Med Ethics 22, 32 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00572-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00572-5