Abstract

Background

More and more studies investigate medical students’ empathy using the Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE). However, no norm data or cutoff scores of the JSE for Japanese medical students are available. This study therefore explored Japanese norm data and tentative cutoff scores for the Japanese translation of the JSE-medical student version (JSE-S) using 11 years of data obtained from matriculants from a medical school in Japan.

Methods

Participants were 1,216 students (836 men and 380 women) who matriculated at a medical school in Japan from 2011 to 2021. The JSE-S questionnaire was administered to participants prior to the start of the program. Data were summarized using descriptive statistics and statistical tests were performed to show the norm data and tentative cutoff scores for male and female students separately.

Results

The score distributions of the JSE-S were moderately skewed and leptokurtic for the entire sample, with indices -0.75 and 4.78, respectively. The mean score (standard deviation) for all participants was 110.8 (11.8). Women had a significantly higher mean score (112.6) than men (110.0; p < 0.01). The effect size estimate of gender difference was 0.22, indicating a small effect size. The low and high cutoff scores for men were ≤ 91 and ≥ 126, respectively, and the corresponding scores for women were ≤ 97 and ≥ 128, respectively.

Conclusions

This study provides JSE-S norm data and tentative cutoff scores for Japanese medical school matriculants, which would be helpful in identifying those who may need further training to enhance their empathy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Empathy can be described as the competence of a physician to understand their patient’s situation, perspective, and feelings; to communicate this understanding and confirm its accuracy; and to act on that understanding with the patient in a helpful (therapeutic) way [1]. Empathy has been described as an essential component of overall physician competence [2]. Previous studies demonstrate the effectiveness of physician empathy in relation to positive patient outcomes among diabetic patients [3, 4]. Moreover, studies also show increased patient enablement [5] and patient satisfaction [6]. Medical students’ empathy has also been reported to be associated with their clinical competence [7, 8].

To date, numerous studies have investigated the level of empathy among medical students in various countries [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Although medical students’ empathy may increase or decrease during their education, their levels of empathy in the first year of medical school have shown a tendency to be higher in Western countries (e.g., the United States [US] and the United Kingdom) than in Asian countries (e.g., India, South Korea, and Japan) [18]. The determinants of why student empathy varies according to geographical regions remain unknown. To explore the factors of geographical differences in empathy among medical students, internationally comparable norm data from different countries or regions are required.

Norm data and cutoff scores of first-year medical students’ empathy in the US [19] and Spain [20] have already been reported using the Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE). The JSE is a validated psychometric instrument specifically developed to measure empathy in the context of patient care among healthcare professional practitioners and students. It has been widely used for different healthcare professional practitioners and students, translated into 56 languages/dialects, and used in at least 85 different countries [21]. A detailed description of the JSE is available elsewhere [22, 23].

Objectives

Several studies on empathy among Japanese medical students have been conducted using the Japanese translation of the JSE [17, 24,25,26]. However, no norm data or cutoff scores for the Japanese JSE among Japanese medical students have been recorded. If norm data and cutoff scores are available, we can classify the students as having lower, moderate, or higher levels of empathy, which allows us to investigate the underlying factors associated with empathy level. In turn, this may help us to identify appropriate intervention measures to increase students’ empathy according to its original level. Therefore, to address this necessity, we explored Japanese norm data and tentative cutoff scores of the JSE, using 11 years of data, from 2011 to 2021, obtained from matriculants enrolled at a medical school in Japan.

Methods

Study design and participants

This descriptive cross-sectional study used data from the medical school of Okayama University in Japan, from April 2011 to April 2021.

Study participants included 1,216 students (836 men and 380 women) who matriculated at the medical school of Okayama University in Japan from the academic years of 2011 to 2021, and who responded to the survey at the beginning of their medical school education (representing a 97.5% response rate).

Instrument

There are currently three versions of the JSE: (1) An “HP” version for physicians and practitioners of all healthcare professions, (2) an “S” version for medical students, and (3) an “HPS” version for students in all healthcare professions other than medicine. These three versions are all very similar in context, with only slight differences in a few words used to adjust the instrument for its target population [19, 27]. In the present study, we used the Japanese translation of the “S” version (JSE-S). The details of the JSE-S have been described previously [11, 19]. Moreover, the validity and reliability of the Japanese translation of the JSE-S have been confirmed [17].

The JSE questionnaire is comprised of 20 question items. Each item is answered on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 7 = “strongly agree” to 1 = “strongly disagree.” The S-version, for example, includes questions such as “Physicians’ understanding of the emotional status of their patients, as well as that of their families, is one important component of the physician–patient relationship.”

Procedure

Prior to the first class of the medical program, which is provided just after entry into medical school each year, we explained the study to the students, orally and in writing, and asked them to participate. We ensured that they were aware that participation was voluntary, that their responses would be kept strictly confidential, that their answers would not affect their academic record, and that the data might be used as aggregated data for statistical analysis. A hard copy of the JSE-S questionnaire was distributed to each student entering classes of 2011–2019; for the 2020 and 2021 classes, it was administered online. Students who consented to participate in the study filled out and submitted the questionnaire.

This study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Okayama University hospital (Approval No. 826 and Ken 2207–024).

Statistical analysis

Submitted questionnaires with missing information on more than four items (of the 20) were considered incomplete and excluded from the analysis. If four or fewer items were missing, each missing value was replaced with the mean score calculated from the completed items [22, 28]. Previous studies have required a minimum JSE score of 50 [22], so questionnaires with a total score of less than 50 were marked as invalid and excluded from this study. However, this was only a negligible amount, as only two participants scored less than 50 on our questionnaire (< 0.3%).

For comparison with previous studies, we summarized the data using descriptive statistics and performed the following statistical tests [19]. First, we summarized the data of the JSE-S scores with descriptive statistics, which included frequency, mean, standard deviation (SD), median, range, skewness, and kurtosis indices across matriculation years. We also calculated the Cronbach’s α coefficient—an index of internal consistency and reliability of the JSE-S across matriculation years. Second, we performed an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the differences in the mean JSE-S scores across matriculation years. Third, we used the χ2 test to determine whether the distribution of gender among the participants was similar across matriculation years. Fourth, we examined the difference in the mean JSE-S scores between male and female students using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. We also calculated Cohen’s d as an estimate of effect size. The effect size d values of 0.8, 0.5, and 0.2 were considered large, medium, and small effect sizes, respectively [29].

Finally, we determined cutoff scores to identify low or high scores. Low and high scores were defined as points below the 7th percentile and above the 93rd percentile, respectively, as indicated by a previous study [19]. As gender differences in the JSE-S have been reported [7, 25, 30], we determined the cutoff scores separately for men and women, from their respective score distributions.

Two-sided p-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The data were analyzed using Stata SE 17.0 for Windows (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

The participants included in the analyses were 1,216 students (836 men and 380 women), and the overall response rate was 97.5% (men 97.1% and women 98.4%).

Descriptive statistics, including the frequency, mean, SD, median, score range, skewness, and kurtosis indices of the JSE-S by matriculation year, are presented in Table 1. The mean score (SD) for all participants was 110.8 (11.8); mean scores varied from a low of 108.4 (13.8) for the matriculants of 2014 to a high of 112.5 (11.6) for the matriculants of 2011. The ANOVA revealed no statistically significant differences in the mean scores across matriculation years (p = 0.16). The skewness index was negative for the entire sample (-0.75) and for each matriculation year (range: -2.17 [for matriculants of 2021] to -0.17 [for matriculants of 2018]). The kurtosis for the entire sample was 4.78 (range: 2.39 [for matriculants of 2020] to 9.54 [for matriculants of 2021]). The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the entire sample was 0.81 (range: 0.75 [for matriculants of 2012, 2017, and 2018] to 0.87 [for matriculants of 2021]).

Table 2 shows the distribution of the participants by matriculation year and gender as well as the gender differences in the JSE-S mean scores by matriculation year. The proportion of men was higher across all matriculation years. However, the gender composition differed across matriculation years (p = 0.007). Women consistently tended to obtain higher scores than men, except in the matriculation year of 2012; however, there were no significant differences in the mean score between men and women in any of the matriculation years. For all participants, women had a significantly higher mean score (112.6) than men (110.0), owing to the large sample size (p = 0.0004). The effect size estimates of the mean score differences between men and women varied according to matriculation year (range: -0.10 [for matriculants of 2012] to 0.42 [for matriculants of 2013]). For all participants, the effect size estimate of gender difference was 0.22, indicating a small effect size.

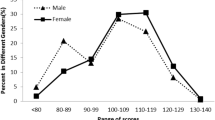

The frequency distributions of JSE-S scores and percentile ranks for men, women, and the full sample are shown in Table 3. The mean (SD) and median for all participants were 110.8 (11.8) and 111, respectively. The low and high cutoff scores for men were ≤ 91 and ≥ 126, respectively, and the corresponding scores for women were ≤ 97 and ≥ 128, respectively.

Discussions

The present study aimed to determine the norm data and tentative cutoff scores for the JSE-S instrument among Japanese medical students, using data of 11 years obtained from a medical school in Japan. The reported norm data have potential implications for medical education in comparing the individual JSE-S scores to determine their relative percentile ranks. For example, the JSE-S score of a male medical student that falls between 121 and 125 would place him in the top 80‒91 percentile relative to the score of another male medical student whose JSE-S score falls between 111 and 115, thus placing him in the 50‒63 percentile.

Comparison with previous studies

Here, we discuss our findings on norm data and tentative cutoff scores for the JSE-S among medical school matriculants in Japan, compared to previous studies conducted in the US (N = 2,637) [19] and Spain (N = 893) [20] for first-year medical students. First, we compared our findings with those of the American study, incorporating 11 years’ data, from 2002 to 2012 [19]. The mean JSE-S scores for this study were higher than those of Japan by approximately two and four points for men and women, respectively. Several factors may contribute to this difference. First, the age at entry to medical school is higher in the US. According to a study reporting the characteristics of matriculants in medical schools in the US, more than 98% of matriculants between 2001 and 2015 were 21 years old or older at the time of entry [31]. The mean age of the US study’s participants was 23.4 years old [19]. In Japan in recent years, approximately 85% of matriculants in medical schools are younger than 21 years at the time of matriculation [32]. Most Japanese students enter medical school immediately or within a few years of completing high school.

Second, matriculants in the US have a broad background in their undergraduate majors, including humanities, arts, and social sciences [33, 34]. A previous study demonstrates that first-year osteopathic medical students in the US who had majored in “Social and Behavioral Sciences” and “Arts and Humanities” had higher mean scores of JSE-S than those with a background in “Chemical and Physical Sciences” [30]. In addition, they have more experience before entering medical school, such as following another career, engaging in family obligations, or international travel, living, and working experiences [35, 36]. Most matriculants in Japan, however, enter medical school directly from high school, with chemistry and physical sciences courses, with the exception of those who may have failed their entrance exam at their first attempt. It is possible that first-year Japanese students had not yet cultivated empathy, having just been freed from the severe effort of passing the highly competitive entrance examination. Thus, matriculants in the US were likely to be more mature personally, with more experiences and exposure to situations that would foster empathy. This may be the reason for the finding of the baseline mean score of the JSE-S being higher among American students than among Japanese students.

The type of survey administration—that is, hard copy questionnaire for the matriculants of 2011–2019 or online questionnaire for the matriculants of 2020–2021—did not affect JSE-S scores (data not shown). This result is consistent with that of the US [19].

Next, we compared our findings with those of a Spanish study conducted in eight medical schools in Madrid in 2019 [20]. The mean JSE scores in Spain were higher than those in Japan by approximately seven and eight points for men and women, respectively. The participants in the Spanish study were first-year medical students who had not yet been in contact with patients, and the mean age when the survey was conducted was 18.9 years; this is similar to our study. Differences in response rates and in the JSE version used for the survey could be factors causing the difference in mean scores between Spain and Japan. The response rates of Spanish and Japanese studies were 59.7 and 97.5%, respectively. While most Japanese students responded to the questionnaire, Spanish students who had relatively high empathy might have selectively responded, leading to higher mean scores among Spanish participants.

The JSE version used in the Spanish study was the HP version for physicians and practitioners of all healthcare professions, instead of the S-version for medical students. The JSE was originally developed to measure medical students’ orientation or attitudes toward physician empathy in patient-care situations; that is, the S-version. Thereafter, the HP version was developed to measure empathy among practicing physicians and other healthcare professionals. Although the two versions are very similar in context, the wording of the HP version was modified slightly for some items, to make them more relevant to caregivers’ empathic behavior, than to empathic orientation or attitudes among physicians. For example, the following appeared in the S-version: “Because people are different, it is difficult for physicians to see things from their patients’ perspectives.” In the HP version, this item was revised to read as follows: “Because people are different, it is difficult for me to see things from my patients’ perspectives” [37]. It is possible that the respondents to the S-version were scored more strictly, as this version refers to the empathy of a physician in general, not the empathy of the respondents themselves. This might have contributed to the lower mean score of the Japanese students who used the JSE-S version, compared with the Spanish students who used the HP version.

Cultural traits may also be important factors that affect empathy. A previous study investigating the difference in mean JSE-S scores in relation to race and ethnicity among American osteopathic medical students showed that Asian students had lower mean scores than White/Caucasian or Hispanic/Latino/Spanish students [30]. In general, Japanese people tend to communicate with others in a manner that is calm, ambiguous, humble, and censoring of themselves [38]. It is likely that many Japanese patients hesitate to express their personal feelings or emotions to others, including medical staff. These culture-specific characteristics might have resulted in differences in empathy scores between the Japanese and American or Spanish students. These differences may also originate from the differences between concepts of medical professionalism in Japanese and Western culture. One article [39] suggests that the Bushido, a Japanese code of personal conduct originating from ancient samurai warriors, may influence the behaviors of modern Japanese doctors. The Bushido contains concepts that differ from the physician charters used in Western medical societies, such as autonomy of the individual, gender roles, and ethical conception. However, these assumptions require further investigation in future research.

Strengths and limitations

The advantages of our study include its relatively large sample size, using 11 years of data, and its high response rates, which enables the provision of norm data and tentative cutoff scores of the JSE-S by gender among Japanese medical students. Several previous studies demonstrate that the mean scores of medical students’ empathy increases after educational programs/interventions. However, there are limited studies investigating educational effectiveness according to the level of empathy. Still, a study in the US reported that students’ empathy scores were lower in clinical years than in preclinical years, and that the decrease in empathy was smaller in students with high baseline empathy than those with low baseline empathy [40]. In contrast, our preliminary data indicate that the effectiveness of professional/educational programs in enhancing students’ empathy tends to be higher in students with moderate baseline empathy than in students with low or high baseline empathy. Thus, determining norm data and cutoff scores would allow us to evaluate educational effects and design educational programs and methods according to the levels of students’ empathy.

Our study has some limitations as well. First, the data were collected at a single institution, which could affect the generalizability of the findings. However, the medical school of the university in this study is typical of national medical schools in Japan in terms of the mean age at matriculation and the gender distribution of matriculants. The proportion of female students in the medical school of this university and that of all national medical schools in Japan between 2011 and 2021 was approximately the same: 31.3 and 33.2%, respectively [41]. When applying to this medical school, students face high levels of competition relative to other medical schools in Japan, but these are not extremely high. Of all 82 medical schools in Japan (national, public, and private), Okayama University is typically ranked in the top 15. Alongside their preparatory studies for the entrance examination, many students also have experience in extra-curricular activities, such as club and volunteer activities. Therefore, the data of this study can be considered representative of all national medical schools in Japan.

Second, we were only able to compare our results with two previous studies, which, like ours, investigated the cutoff scores of first-year medical students and separated them by gender. We could not include any other studies due to the unavailability of comparable measures.

Third, we were not able to include the students’ age and experience as variables in the analyses due to the unavailability of these data. Empathy may be influenced by students’ age and experience before entering medical school. However, as most Japanese students enter medical school immediately after or within a few years of completing high school, we believe that these variables would not substantially influence the results.

Forth, in a future study, we need to confirm the validity and practicality of the cutoff scores reported in this study by comparing high-scoring (above the top JSE-S cutoff score) and low-scoring (below the bottom cutoff score) students on measures of clinical competence to examine whether differences in clinical competence ratings present as expected.

Conclusions

The present study provides empirical data from a relatively large data sample of 11 years, which can be used as proxy norm data and tentative cutoff scores for identifying the high and low empathy scores of the JSE-S among Japanese medical school matriculants. Our findings may be nationally comparable and can be used as representative data for national medical schools in Japan. The findings could also be helpful in identifying those who may need further training to enhance their empathy and locating the relative standing of a particular individual or group on the score distribution of the JSE-S.

Availability of data and materials

The de-identified datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- JSE:

-

Jefferson Scale of Empathy

- JSE-S:

-

JSE-medical student version

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- US:

-

The United States

References

Mercer SW, Reynolds WJ. Empathy and quality of care. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(Suppl):S9-12.

Hojat M. Empathy in Health Professions Education and Patient Care. 1st ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):359–64.

Del Canale S, Louis DZ, Maio V, Wang X, Rossi G, Hojat M, et al. The relationship between physician empathy and disease complications: an empirical study of primary care physicians and their diabetic patients in Parma. Italy Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1243–9.

Mercer SW, Neumann M, Wirtz M, Fitzpatrick B, Vojt G. General practitioner empathy, patient enablement, and patient-reported outcomes in primary care in an area of high socio-economic deprivation in Scotland–a pilot prospective study using structural equation modeling. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(2):240–5.

Hojat M, Louis DZ, Maxwell K, Markham FW, Wender RC, Gonnella JS. A brief instrument to measure patients’ overall satisfaction with primary care physicians. Fam Med. 2011;43(6):412–7.

Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, Veloski JJ, Erdmann JB, et al. Empathy in medical students as related to academic performance, clinical competence and gender. Med Educ. 2002;36(6):522–7.

Casas RS, Xuan Z, Jackson AH, Stanfield LE, Harvey NC, Chen DC. Associations of medical student empathy with clinical competence. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(4):742–7.

Quince TA, Kinnersley P, Hales J, Silva A, Moriarty H, Thiemann P, et al. Empathy among undergraduate medical students: a multi-centre cross-sectional comparison of students beginning and approaching the end of their course. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:92.

Duarte MI, Branco MC, Raposo ML, Rodrigues PJ. Empathy in medical students as related to gender, year of medical school and specialty interest. South East Asian J Med Educ. 2015;9(1):50–3.

Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, Brainard G, Herrine SK, Isenberg GA, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med. 2009;84(9):1182–91.

Santos MA, Grosseman S, Morelli TC, Giuliano ICB, Erdmann TR. Empathy differences by gender and specialty preference in medical students: a study in Brazil. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:149–53.

Igde FA, Sahin MK. Changes in empathy during medical education: an example from Turkey. Pak J Med Sci. 2017;33(5):1177–81.

Tariq N, Tayyab A, Jaffery T. Differences in empathy levels of medical students based on gender, year of medical school and career choice. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2018;28(4):310–3.

Chatterjee A, Ravikumar R, Singh S, Chauhan PS, Goel M. Clinical empathy in medical students in India measured using the Jefferson Scale of Empathy-student version. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2017;14:33.

Roh MS, Hahm BJ, Lee DH, Suh DH. Evaluation of empathy among Korean medical students: a cross-sectional study using the Korean version of the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy. Teach Learn Med. 2010;22(3):167–71.

Kataoka HU, Koide N, Ochi K, Hojat M, Gonnella JS. Measurement of empathy among Japanese medical students: psychometrics and score differences by gender and level of medical education. Acad Med. 2009;84(9):1192–7.

Ponnamperuma G, Yeo SP, Samarasekera DD. Is empathy change in medical school geo-socioculturally influenced? Med Educ. 2019;53(7):655–65.

Hojat M, Gonnella JS. Eleven years of data on the Jefferson Scale of Empathy-Medical Student Version (JSE-S): proxy norm data and tentative cutoff scores. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24(4):344–50.

Blanco Canseco JM, Blanco Alfonso A, Caballero Martínez F, Hawkins Solís MM, Fernández Agulló T, Lledó García L, et al. Medical empathy in medical students in Madrid: a proposal for empathy level cut-off points for Spain. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(5): e0267172.

Thomas Jefferson University. Philadelphia: Jefferson Scale of Emapthy. Available from: https://www.jefferson.edu/academics/colleges-schools-institutes/skmc/research/research-medical-education/jefferson-scale-of-empathy.html. [Cited 24 Jun 2022].

Hojat M. Empathy in Patient Care. 1st ed. New York: Springer Science & Business Media; 2007.

Hojat M, LaNoue M. Exploration and confirmation of the latent variable structure of the Jefferson scale of empathy. Int J Med Educ. 2014;5:73–81.

Kataoka H, Iwase T, Ogawa H, Mahmood S, Sato M, DeSantis J, et al. Can communication skills training improve empathy? A six-year longitudinal study of medical students in Japan. Med Tech. 2019;41(2):195–200.

Fukuyasu Y, Kataoka HU, Honda M, Iwase T, Ogawa H, Sato M, et al. The effect of Humanitude care methodology on improving empathy: a six-year longitudinal study of medical students in Japan. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):316.

Abe K, Niwa M, Fujisaki K, Suzuki Y. Associations between emotional intelligence, empathy and personality in Japanese medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):47.

Hojat M, DeSantis J, Shannon SC, Mortensen LH, Speicher MR, Bragan L, et al. The Jefferson Scale of Empathy: a nationwide study of measurement properties, underlying components, latent variable structure, and national norms in medical students. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2018;23(5):899–920.

Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Maxwell K. Jefferson Scales of Empathy (JSE): Professional Manual & User's Guide. Philadelphia: Jefferson Medical College - Center for Research in Medical Education and Health Care; 2009.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New York: Erlbaum; 1988.

Hojat M, DeSantis J, Shannon SC, Speicher MR, Bragan L, Calabrese LH. Empathy as related to gender, age, race and ethnicity, academic background and career interest: a nationwide study of osteopathic medical students in the United States. Med Educ. 2020;54(6):571–81.

Zhang D, Li G, Mu L, Thapa J, Li Y, Chen Z, et al. Trends in medical school application and matriculation rates across the United States From 2001 to 2015: implications for health disparities. Acad Med. 2021;96(6):885–93.

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technolgy, Japan. Tokyo: Preliminary report on the results of an urgent survey on ensuring fairness in the selection of enrollees in the faculty of medicine (press release), 2018. Available from: https://www.mext.go.jp/component/a_menu/education/detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2018/09/10/1409128_002_1.pdf. [Cited 7 Jul 2022].

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Washington, DC: From premed to physician: Pursuing a medical career, 2017. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2017/article/premed.htm. [Cited 7 Jul 2022].

Association of American Colleges. Washington, DC: 2021 FACTS: Applicants and Matriculants Data, Table A-17: MCAT and GPAs for Applicants and Matriculants to U.S. Medical Schools by Primary Undergraduate Major, 2021–2022. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/interactive-data/2021-facts-applicants-and-matriculants-data. [Cited 7 Jul 2022].

Association of American Colleges. Washington, DC: Diversity in Medical Education: Facts & Figures 2012. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/media/9951/download. [Cited 7 Jul 2022].

Association of American Colleges. Washington, DC: Matriculating Student Questionnaire: 2019 All Schools Summary Report. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/media/38916/download. [Cited 7 Jul 2022].

Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, Magee M. Physician empathy in medical education and practice: experience with the Jefferson scale of physician empathy. Semin Integr Med. 2003;1(1):25–41.

Nakai F. The role of cultural influences in Japanese communication: a literature review on social and situational factors and Japanese indirectness. Intercult Commun Stud. 2002;14:99–122.

Nishigori H, Harrison R, Busari J, Dornan T. Bushido and medical professionalism in Japan. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):560–3.

Chen DCR, Kirshenbaum DS, Yan J, Kirshenbaum E, Aseltine RH. Characterizing changes in student empathy throughout medical school. Med Teach. 2012;34(4):305–11.

Statistics Bureau of Japan. Tokyo: Statistical tables of the Basic School Survey of Japan (2011 - 2021): Higer education institutes, Undergraduate and postgraduate, Table: Number of matriculants by department. Available from: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/. (in Japanese). [Cited 12 Jul 2022].

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Joseph S. Gonnella, MD, Ph.D. and Mohammadreza Hojat, Ph.D. for useful discussions and advice. We would like to thank Toshihide Iwase, MD and Chie Beppu for their contribution to data management. We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

This study was supported, in part, by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI grants number [21K01860].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HUK designed the study protocols. HUK, CF, MW and MO collected the data. AT analyzed the data. HUK and AT prepared the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Okayama University hospital (Approval No. 826 and Ken 2207–024). The authors confirmed that all the methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kataoka, H.U., Tokinobu, A., Fujii, C. et al. Eleven years of data on the Jefferson Scale of Empathy – medical student version: Japanese norm data and tentative cutoff scores. BMC Med Educ 23, 81 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03977-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03977-5