Abstract

Background

Nursing students’ empathy and positive attitudes toward elderly people could help provide improved elderly care in their future practice. This study aimed to investigate the effects of empathy skills training on nursing students’ empathy and attitudes toward elderly people.

Methods

This quasi-experimental study was conducted in Yasuj, Iran in 2014. The sample consisted of 63 students at Hazrat Zeinab Nursing and Midwifery School who were randomly divided into a control (n = 31) and an intervention group (n = 32). The intervention group attended an eight-hour workshop on empathy skills that was presented through lectures, demonstration, group discussions, scenarios, and questioning. The data were collected using the Persian versions of Kogan’s Attitudes towards Old People Scale and Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy-Health Professionals Version. Then, the data were entered into the SPSS software, version 19 and were analyzed using descriptive statistics, chi-square test, t-test, and repeated measures analysis of variance.

Results

The results showed that the empathy skills training program had a significant impact on the students’ mean scores of empathy and attitudes toward elderly people (p < 0.001). The intervention group’s mean score of empathy increased from 77.8 (SD = 10.7) before the intervention to 86 (SD = 7.3) immediately after that and 85.2 (SD = 8.9) 2 months later. Their mean score of attitude also increased from 110.8 (SD = 10.9) before the intervention to 155.2 (SD = 23.4) immediately after the intervention and 158.6 (SD = 23.2) 2 months later. Additionally, the empathy and attitude scores of the intervention group were significantly higher than those for control group immediately and 2 months after the intervention.

Conclusions

Empathy skills training improved the nursing students’ empathy and attitudes towards elderly people. Therefore, empathy training is recommended to be incorporated into the undergraduate nursing curriculum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the present century, as a result of rise in life expectancy, old age is becoming an important worldwide phenomenon. World Health Organization (WHO) defined elderly people as individuals aged 60 years and above. According to the statistics released by WHO, the population of elderly people aged 60 years and above in the world was 900 million in 2015, which has been estimated to reach 1.2 billion by 2025 and 2 billion by 2050 [1]. In Iran, the elderly population increased by 4 times during 1967 to 2011 [2]. In 2011, individuals older than 65 years comprised 5.7% of Iran’s population [3]. It has been estimated that nearly 30% of the Iranian population will be 60 years old and above by 2050 [1].

Elderly people have various healthcare needs. As a result of the physiological changes that accompany old age, elderly individuals comprise the most vulnerable group to various diseases. For instance, three out of four Americans aged 65 years and above suffered from multiple chronic conditions, and 93% of Medicare was spent for individuals with multiple chronic conditions [4]. Some chronic diseases, in turn, lead to disablement in activities and frequent hospitalizations [5]. Other health problems, such as depression and cognitive impairment, may also interfere with elderly individuals’ communication abilities and cause other special healthcare needs. The prevalence of cognitive impairment was 7.85% in an Iranian elderly population [6].

Rapid growth of the elderly population and their vulnerability to various health disorders lead to increased number of elderly patients needing healthcare services. Nurses, as members of the healthcare team, are becoming increasingly responsible for caring for elderly people. Additionally, they have a key role in ensuring patients’ safety and acting on their behalf [7]. Elderly care may be affected by various factors, including nurses’ attitudes towards elderly people. Hence, nurses’ attitudes towards elderly people could determine the quality of therapeutic interaction between nurses and elderly patients [8] as well as nurses’ willingness to care for these patients [9]. According to studies, some nurses and nursing students had negative attitudes towards elderly individuals [10,11,12] and were not willing to consider elderly care as a part of their future jobs [13]. A cross-sectional Iranian study also indicated that 54.3% of nurses had negative attitudes towards older adults [10]. Thus, measures have to be taken to improve nurses’ attitudes towards elderly care, especially in health educational settings.

The proper relationship between healthcare providers and elderly people is important in achieving the goals of the care plan [14]. Nurses, compared to other members of the healthcare team, spend more time interacting with patients. Therefore, it is especially important to train them in establishing positive relationships with patients [15].

Empathy is a basic competency of helping relationship and an integral component of person-centered care. Person-centered care, in turn, improves the quality of care and patients’ outcomes [14, 16]. Empathy towards patients increased patients’ satisfaction and reduced their distress [17]. Empathy has been defined as a cognitive attribute involving an understanding of patients’ experiences, concerns, and perspectives together with the ability to communicate this understanding and the intention to help [18]. Iranian hospitalized elderly patients reported their needs for an empathetic understanding [19]. On the other hand, a qualitative study showed that nurse assistance communication with elderly people in home care was mostly task-oriented and that person-oriented communication had to be promoted in nurse-elderly communication [20]. In addition, it has been reported that nursing students’ empathy towards elderly people somewhat decreased during academic education [21, 22]. Empathy is a teachable competency [23], which is particularly important for students in the last years of their education. Therefore, it is important to investigate evidence-based interventions to improve nursing students’ empathy and attitudes towards elderly people.

A systematic review reported that only a few studies on healthcare students investigated the effect of workshops on students’ attitudes towards elderly people, and that some of these interventional studies lacked control groups or randomization [24]. Therefore, further studies have to be conducted in this domain to examine the effects of workshops on nursing students’ attitudes towards elderly people. It should be noted that traditional nursing education lacked the appropriate teaching methods to train nursing students about empathy skills. Hence, it is essential to find effective ways to empower nursing students with these skills [16]. Evidence has revealed the beneficial effects of training nursing students regarding non-technical skills on their attitudes [25, 26]. However, there is not sufficient evidence to determine whether empathy-building workshop can improve nursing students’ empathy and attitudes towards elderly people. Therefore, the present study aims to explore the effects of training nursing students regarding empathy skills on their empathy and attitudes towards elderly individuals (≥ 60 years old). The content of this training workshop and the study population (third- and fourth-year nursing students) make the study unique among the studies with empathy-building interventions. Moreover, it was previously reported that a short-term intervention improved health-care students’ empathy towards elderly people, while this improvement declined over time [27]. Therefore, the present study examined the effects of empathy skills training both immediately and 2 months after the intervention.

Methods

Design and sample

The present quasi-experimental study with a pretest/posttest control design was conducted in 2014. All third- and fourth-year nursing students at Hazrat Zeinab Nursing and Midwifery School of Yasuj, Iran were included in the study. Then, the 70 students were randomly divided into a control and an intervention group through block randomization. It should be noted that during the study, four students from the control group and three students from the intervention group were excluded due to unwillingness to participate, and the study was continued with 63 students (32 in the intervention group and 31 in the control group).

The inclusion criteria of the study were willingness to participate, being a third- or fourth-year nursing student, and not having taken any empathy courses in the past 6 months. In case the students were unwilling to continue participation in the study or were participating in another educational program at the same time, they were excluded.

Data collection and intervention

The study data were collected using the Persian versions of Kogan’s Attitudes towards Old People Scale (KAOP) and Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy-Health Professionals Version (JSPE-HP). JSPE-HP was a 20-item questionnaire, all of which addressed the respondents’ level of empathy with patients. The items were answered based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scores could range from 20 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater empathy with elderly patients. The scores of 77 and below were considered poor, those between 78 and 88 were considered moderate, and scores above 88 were considered good. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of the questionnaire were evaluated in Hashemipour’s study (2012) in Iran. Accordingly, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.83 [28].

KAOP contained 34 positive and negative items; 17 items about positive attitudes and 17 items about negative attitudes. It evaluated the respondents’ attitudes towards elderly people based on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). The negative items were scored reversely, such a way that the scores ranged from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (6). The total score of the questionnaire could range from 34 to 204. The scores of 111 and below were considered poor, those between 112 and 118 were considered moderate, and scores above 118 were considered good (20). Several studies have indicated KAOP as a reliable and valid instrument for evaluating individuals’ attitudes towards elderly individuals. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the whole scale (positive and negative items) has been reported to vary from 0.79 to 0.87 [29].

The students in both groups were asked to complete the demographic data questionnaire, JSPE-HP, and KAOP. The intervention consisted of an eight-hour workshop on empathy skills that was held at the college for 2 days. The content of the workshop was designed by the researchers and reviewed and revised by some of the college professors. The workshop was mainly based on constructivist learning theory. This theory considers the learners active in the construction of knowledge through real life experiences. Social and cultural aspects of learning and learners’ ideas about the learning topic are emphasized, as well [30]. All students in the intervention group participated in the same workshop. The students were informed about the date of the workshop in advance. The content was presented through lectures, role play, group discussions, scenarios, clip presentation, and questioning. In the workshop, the students were informed about the epidemiological transition for elderly people, physiological changes in elderly people, professional relationship with elderly people, self-awareness, and definition and examples of empathy towards patients. The topics, learning objectives, activities, and timetable have been presented in Table 1. The lectures on self-awareness and empathy were presented by experienced psychology professors, and the rest of the material was presented by one of the researchers. The students in both intervention and control groups completed the questionnaires before, immediately after, and 2 months after the intervention.

Data analysis

The collected data were entered into the SPSS statistical software, version 19 and were analyzed using descriptive statistics, chi-square test, independent t-test, Mann-Whitney, and repeated measures ANOVA. The effect sizes of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 were considered small, medium, and large, respectively [31].

Results

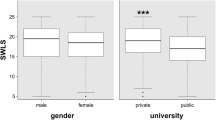

The majority of the participants in both the control (53.1%) and the intervention group (58.1%) were female, with the mean age of 22.7 (SD = 1.62) years. Based on the results of chi-square test and independent t-test, there were no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) between the two groups in terms of demographic characteristics. Also, there was no difference between two groups regarding the study variables before the intervention (Tables 2 and 3).

The pretest total mean score of the students’ attitude was 110.4 (SD = 11.5), which indicates the students’ poor attitudes towards elderly people. In addition, the pretest total mean score of empathy was 78.1 (SD = 10.3), which indicates the nursing students’ moderate level of empathy (Table 3).

In terms of the mean scores of attitude, there was a significant difference between the intervention and control groups immediately (p < 0.001) and 2 months after the intervention (p < 0.001). There were also significant differences in both intervention (p < 0.001) and control groups (p < 0.001) over time. The effect size for attitude scores was medium in the intervention and small in the control group (0.71 vs. 0.36) (Table 4). The intervention group’s mean score of attitude rose from 110.8 (SD = 10.9) before the intervention to 155.2 (SD = 23.4) immediately after that. On the other hand, the control group’s mean score of attitude rose from 110 (SD = 12.3) before the intervention to 126.6 (SD = 13) immediately after that. Two months after the intervention, the mean score of attitude was 158.6 (SD = 23.2) in the intervention group and 128.4 (SD = 13.3) in the control group (Table 4). The results of Mann-Whitney test revealed that the posttest/pretest mean difference of the attitude score was significantly higher in the intervention group compared to the control group immediately after (44.4 (SD = 27.09) vs. 16.6 (SD = 16.6), p < 0.001) and 2 months after the intervention (47.8 (SD = 26.7) vs. 18.4 (SD = 17), p < 0.001). These indicate the effectiveness of the intervention in the intervention group.

In terms of the mean score of empathy, there was a significant difference between the intervention and control groups immediately (p < 0.001) and 2 months after the intervention (p = 0.004). Moreover, there were significant differences in this regard in the intervention group over time (p < 0.001). The effect size of the intervention group’s empathy score was small (0.36). The intervention group’s mean score of empathy rose from 77.8 (SD = 10.6) before the intervention to 86 (SD = 7.3) after that (an 8.2-score increase). However, the control group’s mean score of empathy declined from 78.6 (SD = 10.1) before the intervention to 76.7 (SD = 11.9) after that (a 1.91-score decrease). Two months after the intervention, the intervention group’s mean score of empathy was 85.2 (SD = 8.9) with a 7.4-score increase compared to before the intervention. On the other hand, the control group’s mean score of empathy was 77.5 (SD = 11.3) with a 1.1-point decrease. Moreover, the intervention group’s mean score of empathy decreased by 0.8 points 2 months after the intervention compared to immediately after that, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.33). However, the change was not significant in the control group (p = 0.32) (Table 4).

Discussion

The results of the current study indicated that the empathy skills training improved the students’ scores of empathy and attitudes towards elderly people. The effect size was small for empathy scores and medium for attitude scores. These indicate that the intervention was somewhat effective in empathy scores and moderately effective in attitude scores. In the workshop, the students were encouraged to discuss aging as well as their past experiences and attitudes towards elderly individuals and to identify their abilities and barriers against showing empathy towards older adults. It seems that these learning contents alongside encouraging active learning and valuing students’ ideas and experiences on the topics that were rooted in the constructivism learning theory contributed to these findings. Similarly, a meta-analysis revealed that constructivist learning approaches were moderately effective in learners’ attitudes towards learning subjects [32]. Another study showed that nursing students used different dynamic learning strategies in their own learning process [33]. The findings of the present study are in agreement with those of other studies that used different interventions. For example, Chen et al. reported that nursing students’ empathy and attitudes towards elderly people improved after they played the role of an older adult in a simulation game [34]. In the same line, an innovative bonding program, including workshop and opportunity to work with elderly people in the community, improved nursing students’ attitudes regarding elderly individuals [35]. On the contrary to these findings, an Iranian study demonstrated that an elderly care plan did not improve nursing students’ attitudes towards elderly people [36].

While empathy-building interventions could improve nursing students’ attitudes toward disabled patients [37], review of the literature revealed no studies indicating the effectiveness of empathy skills training in students’ attitudes towards elderly people. Therefore, the present study findings could not be compared to those of other studies. Hence, these findings may provide a novel piece of knowledge in this field. Accordingly, empathy-oriented workshops are recommended to improve nursing students’ attitudes and empathy towards elderly people. This will help prepare them to communicate effectively with elderly individuals in their future professional performance.

Although the change in the control group’s mean score of attitudes towards elderly people was significant, it was significantly lower than that of the intervention group. The change in the control group’s attitude scores might be attributed to the effect of their teachers and other nurses as role models or other factors out of this study scope.

This study did not aim to investigate the effect of the intervention on the students’ willingness to work with elderly patients. Thus, it could not be concluded that the students’ willingness to care for elderly people increased. This is recommended to be examined in future studies.

At the beginning of the present study, all nursing students reported poor attitudes towards elderly people, which have been reported by other studies, as well. Tabiei et al. found that Iranian nursing students had an unsatisfactory attitude towards care for elderly patients with cardiovascular diseases [38]. Similarly, Sanagoo et al. concluded that adolescents, young adults, and young college students had the most negative attitudes towards elderly people [29]. In addition, an Iranian study showed that third-year college students had neutral attitudes and first-year ones had negative attitudes towards elderly individuals [39]. In contrast, other studies found that nurses and nursing students had satisfactory attitudes towards elderly people [40, 41]. These discrepancies might be attributed to differences in sample sizes, research populations, or even cultural and social differences. Cultural aspects should be deliberately taken into account in studies on attitudes towards and communication with elderly people. A study on nurses and nursing students in six different countries showed different attitudes towards older people [42]. In eastern countries, respect for elderly individuals is a cultural value and older persons are considered as wise people. However, Huang’s study indicated that undergraduate students from western countries had more favorable attitudes towards older adults in comparison to those from eastern countries [43].

Limitations

The students in the intervention group were asked not to communicate with other students about the workshop until the end of study. In addition, the intervention group students were not provided with any printed materials to avoid data contamination between the two groups. However, the possibility of data contamination could not be neglected. Moreover, the mid-term effects of the intervention were assessed after 2 months. Data collection in more extended times could assess the long-term effects of the intervention. Furthermore, self-assessed empathy and attitude scores of the nursing students were used in this study. More objective assessments, such as students’ performance in empathy skills and their willingness to care for elderly people, could reveal study outcomes and students’ learning transfer in practice more efficiently. Another study limitation was related to the challenges of using KAOP for data collection since it has been suggested that the questionnaire needs updating [44].

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that development and execution of a unique 8-h workshop on empathy significantly improved the intervention group’s scores of empathy and attitude toward elderly people. Empathy is a teachable skill and policymakers at nursing education institutions are recommended to use the results of the present study and incorporate empathy skills training into undergraduate nursing education. This may serve to achieve two goals; reinforcing students’ empathy towards elderly people and improving their attitudes toward older adults.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of Variances

- JSPE-HP:

-

Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy-Health Professionals Version

- KAOP:

-

Kogan’s Attitudes towards Old People Scale

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Oraganization. 2018. Ageing and health. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health. Accessed 20 June 2018.

Afshar PF, Asgari P, Shiri M, Bahramnezhad F. A review of the Iran's elderly status according to the census records. Galen Med J. 2016;5(1):1–6.

Noroozian M. The elderly population in Iran: an ever growing concern in the health system. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2012;6(2):1.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multiple chronic conditions. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/multiple-chronic.htm. Accessed 10 June 2018.

Longman JM, Rolfe MI, Passey MD, Heathcote KE, Ewald DP, Dunn T, Barclay LM, Morgan GG. Frequent hospital admission of older people with chronic disease: a cross-sectional survey with telephone follow-up and data linkage. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:373.

Gholamzadeh S, Heshmati B, Mani A, Petramfar P, Baghery Z. The prevalence of alzheimer’s disease; its risk and protective factors among the elderly population in Iran. Shiraz E Med J. 2017;18(9):e57576. https://doi.org/10.5812/semj.57576.

Amiri M, Khademian Z, Nikandish R. The effect of nurse empowerment educational program on patient safety culture: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:158.

Deasey D, Kable A, Jeong S. Influence of nurses’ knowledge of ageing and attitudes towards older people on therapeutic interactions in emergency care: a literature review. Australas J Ageing. 2014;33(4):229–36.

Zhang S, Liu Y-H, Zhang H-F, Meng L-N, Liu P-X. Determinants of undergraduate nursing students’ care willingness towards the elderly in China: attitudes, gratitude and knowledge. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;43:28–33.

Arani MM, Aazami S, Azami M, Borji M. Assessing attitudes toward elderly among nurses working in the city of Ilam. Int J Nurs Sci. 2017;4(3):311–3.

Abreu M, Caldevilla N. Attitudes toward aging in Portuguese nursing students. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015;171:961–7.

Celik SS, Kapucu S, Tuna Z, Akkus Y. Views and attitudes of nursing students towards ageing and older patients. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2010;27(4):24.

Rathnayake S, Athukorala Y, Siop S. Attitudes toward and willingness to work with older people among undergraduate nursing students in a public university in Sri Lanka: a cross sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;36:439–44.

Hafskjold L, Sundler AJ, Holmström IK, Sundling V, van Dulmen S, Eide H. A cross-sectional study on person-centred communication in the care of older people: the COMHOME study protocol. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e007864.

Zeighami R, Rafiie F. Concept analysis of empathy in nursing. J Qual Res Health Sci. 2012;1(1):27–33.

Bauchat JR, Seropian M, Jeffries PR. Communication and empathy in the patient-centered care model—why simulation-based training is not optional. Clin Simul Nurs. 2016;12(8):356–9.

Lelorain S, Brédart A, Dolbeault S, Sultan S. A systematic review of the associations between empathy measures and patient outcomes in cancer care. Psycho-Oncology. 2012;21(12):1255–64.

Hojat M, DeSantis J, Gonnella JS. Patient perceptions of Clinician's empathy: measurement and psychometrics. J Patient Exp. 2017;4(2):78–83.

Reje N, Haravi Karimvi M, Froghan M. The needs of hospitalized elderly patients: a qualitative study. SIJA. 2010;5(1):42–52.

Kristensen DV, Sundler AJ, Eide H, Hafskjold L, Ruud I, Holmström IK. Characteristics of communication with older people in home care: a qualitative analysis of audio recordings of home care visits. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(23–24):4613–21.

Ward J, Cody J, Schaal M, Hojat M. The empathy enigma: an empirical study of decline in empathy among undergraduate nursing students. J Prof Nurs. 2012;28(1):34–40.

Ferri P, Rovesti S, Panzera N, Marcheselli L, Bari A. Empathic attitudes among nursing students: a preliminary study. Acta Biomed. 2017;88(S. 3):22–30.

Richardson C, Percy M, Hughes J. Nursing therapeutics: teaching student nurses care, compassion and empathy. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(5):e1–5.

Ross L, Jennings P, Williams B. Improving health care student attitudes toward older adults through educational interventions: a systematic review. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2018;39(2):193–213.

Khademian Z, Pishgar Z, Torabizadeh C. Effect of Training on the Attitude and Knowledge of Teamwork Among Anesthesia and Operating Room Nursing Students: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Shiraz E Med J. 2018;19(4):e61079. https://doi.org/10.5812/semj.610179.

Vivien Rodgers R, GDGN M. Shaping student nurses’ attitudes towards older people through learning and experience. Nurs Prax N Z. 2011;27(3):13.

Van Winkle LJ, Fjortoft N, Hojat M. Impact of a workshop about aging on the empathy scores of pharmacy and medical students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(1):9.

Hashemipour M, Karami MA. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of JSPE-HP questionnaire (Jefferson scale of physician empathy-health professionals version). J Kerman Univ Med Sci. 2012;19(2):201–11.

Sanagoo A, Bazyar A, Chehregosha M, Gharanjic S, Noroozi M, Pakravanfar S, Asayesh H, Jouybari L. People attitude toward elderly in Golestan province. Gorgan J Nurs Midwifery. 2011;8(2):24–9.

Fernando SY, Marikar FM. Constructivist teaching/learning theory and participatory teaching methods. J Curriculum Teach. 2017;6(1):110.

Gibson DB. Revised title: effect size as the essential statistic in developing methods for mTBI diagnosis. Front Neurol. 2015;6:126.

Semerci Ç, Batdi V. A meta-analysis of constructivist learning approach on learners’ academic achievements, retention and attitudes. J Educ Train Stud. 2015;3(2):171–80.

Shirazi F, Sharif F, Molazem Z, Alborzi M. Dynamics of self-directed learning in M.Sc. nursing students: a qualitative research. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2017;5(1):33-41.

Chen AM, Kiersma ME, Yehle KS, Plake KS. Impact of the geriatric medication game® on nursing students’ empathy and attitudes toward older adults. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(1):38–43.

Lamet AR, Sonshine R, Walsh SM, Molnar D, Rafalko S. A pilot study of a creative bonding intervention to promote nursing students’ attitudes towards taking care of older people. Nurs Res Pract. 2011;2011:537634.

Adib-Hajbaghery M, Mohamadghasabi M, Masoodi Alavi N. Effect of an elderly care program on the nursing students’ attitudes toward the elderly. SIJA. 2014;9(3):189–96.

Geckil E, Kaleci E, Cingil D, Hisar F. The effect of disability empathy activity on the attitude of nursing students towards disabled people: a pilot study. Contemp Nurse. 2017;53(1):82–93.

Tabiei S, Saadatjoo S, Hoseinian S, Naseri M, Eisanejad L, Ghotbi M, Tahernia H. Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes towards care delivery to the aged with cardiovascular diseases. Mod Care J. 2011;7(3):41–7.

Hosseini Seresht A, Nasiri Ziba F, Kermani A, Hosseini F. Assesment of nursing students and clinial nurses’ attitude toward elderly care. Iran J Nurs. 2006;19(45):57–67.

Askaryzade mahani M, Arab M, Mohammadalizade S, Haghdoost A. Staff nurses knowledge of aging process and their attitude toward elder people. Iran J Nurs. 2008;21(55):19–27.

Faronbi JO, Adebowale O, Faronbi GO, Musa OO, Ayamolowo SJ. Perception knowledge and attitude of nursing students towards the care of older patients. IJANS. 2017;7:37–42.

Kydd A, Engström G, Touhy TA, Newman D, Skela-Savič B, Touzery SH, Zurc J, Galatsch M, Ito M, Fagerberg I. Attitudes of nurses, and student nurses towards working with older people and to gerontological nursing as a career in Germany, Scotland, Slovenia, Sweden, Japan and the United States. Int J Nurs Educ. 2014;6(2):177–85.

Huang C-S. Undergraduate students’ knowledge about aging and attitudes toward older adults in east and west: a socio-economic and cultural exploration. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2013;77(1):59–76.

Flores R: Critical synthesis package: Kogan’s attitudes toward old people scale. https://www.mededportal.org/publication/10325/#302172. Accessed 10 June 2018.

Acknowledgements

The present study was extracted from an MSC thesis by Maryam Khastavaneh and approved and financially supported by the Research Vice-chancellor of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (grant No. 93-7209). Hereby, the researchers would like to thank the authorities of the university. They would also like to thank Dr. M. Faghih at Center for Development of Clinical Research at Namazi Hospital for collaboration in statistics and data analysis. They are also grateful for Ms. A. Keivanshekouh at the Research Improvement Center of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for improving the use of English in the manuscript. Last but not least, the nursing students are acknowledged for their sincere cooperation in the study.

Funding

The present study was financially supported by the Research Vice-chancellor of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (grant No. 93–7209). The funding body did not play any roles in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset of the present study is available upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design and finally approved the manuscript. SaGh and ZKh participated in data analysis, interpretation, drafting the article, and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. MKh participated in data collection, conducting the intervention, data analysis, and drafting the manuscript. SoGh participated in data interpretation and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (No. 9379–7209). At first, introduction papers were issued and the researchers visited Hazrat Zeinab Nursing and Midwifery School of Yasuj, Iran and made the necessary arrangements with the authorities. Additionally, the study objectives and certain research ethics were explained to the students and their informed consent forms were obtained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gholamzadeh, S., Khastavaneh, M., Khademian, Z. et al. The effects of empathy skills training on nursing students’ empathy and attitudes toward elderly people. BMC Med Educ 18, 198 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1297-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1297-9