Abstract

Background

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has gained widespread application in treating chronic heart failure (CHF) secondary to coronary heart disease (CHD). However, the sound clinical evidence is still lacking. Corresponding clinical trials vary considerably in the outcome measures assessing the efficacy of TCM, some that showed the improvement of clinical symptoms are not universally acknowledged. Rational outcome measures are the key to evaluate efficacy and safety of each treatment and significant elements of a convincing clinical trial. We aimed to summarize and analyze outcome measures in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of TCM in treating CHF caused by CHD, subsequently identify the present problems and try to put forward solutions.

Methods

We systematically searched databases including Embase, PubMed, Cochrane Library, CBM, CNKI, VIP and Wanfang from inception to October 8, 2018, to identify eligible RCTs using TCM interventions for treating CHF patients caused by CHD. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) was searched to include Cochrane systematic reviews (CSRs) of CHF. Two authors independently assessed the risk of bias of the included RCTs according to the Cochrane Handbook. Outcome measures of each trial were extracted and analyzed those compared with the CSRs. We also evaluated the reporting quality of the outcome measures.

Results

A total of 31 RCTs were included and the methodology quality of the studies was generally low. Outcome measures in these RCTs were mortality, rehospitalization, efficacy of cardiac function, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), 6 min’ walk distance (6MWD) and Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), of which mortality and rehospitalization are clinical end points while the others are surrogate outcomes. The reporting rate of mortality and rehospitalization was 12.90% (4/31), the other included studies reported surrogate outcomes. As safety measure, 54.84% of the studies reported adverse drug reactions. Two trials were evaluated as high in reporting quality of outcomes and that of the other 29 studies was poor due to lack of necessary information for reporting.

Conclusions

The present RCTs of TCM in treating CHF secondary to CHD did not concentrate on the clinical end points of heart failure, which were generally small in size and short in duration. Moreover, these trials lacked adequate safety evaluation, had low quality in reporting outcomes and certain risk of bias in methodology. For objective assessment of the efficacy and safety of TCM in treating CHF secondary to CHD, future research should be rigorous designed, set end points as primary outcome measures and pay more attention to safety evaluation throughout the trial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart Failure (HF), a clinical syndrome of the dysfunction of ventricular filling or ejection led by the abnormality of cardiac structure and function, affects about 26 million people around the world [1]. The prevalence of HF is 1–2% of the adult population in developed countries [2, 3] and in China there are about 4.5 million patients of HF [4]. Although the treatment of Chronic Heart Failure (CHF) has made great progress, the mortality and rehospitalization of CHF remain high, only half of patients could survive for more than 5 years [5, 6]. The mortality of hospitalized patients with CHF was 4.1% according to the China-HF registry study [7]. From 2000 to 2010, the cardiovascular hospitalization of CHF has not decreased [8].

Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) is the first cause of CHF among all the primary diseases [9, 10], so that the prevention and treatment of CHF caused by CHD is a significant part of cardiovascular health decisions. Traditional Chinese medicine has been widely used to treat all kinds of CHF which could effectively reduce the levels of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) [11]. However, evidence from TCM clinical trials has not been universally acknowledged in the international medical system nor been included in clinical practice guidelines. The available randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are suboptimal with diverse outcome measures, many of which only showed the improvement of symptoms. To understand the status quo of outcome measures in RCTs of TCM in treating CHF caused by CHD, we conducted a systematic review to evaluate the outcome measures, identify relevant problems and try to put forward solutions.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We included RCTs meeting the following criteria: (1) performed in CHF patients with CHD as primary disease (2) assessing TCM treatment compared with a control group (without restriction). Exclusion criteria were: (1) duplicate publication (2) studies without full text.

Information sources

Electronic databases including Embase, PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Scientific Journal Database (VIP), Wanfang and Chinese Biomedicine Literature Database (CBM) were searched from inception to October 8, 2018. Bibliographies of selected articles were also consulted in search of additional trials not detected in the initial searches.

We also searched Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) to collect Cochrane systemic reviews (CSRs) of CHF for comparative analysis.

Search

We conducted a systematic search. “Medicine, Chinese Traditional [MeSH]”, “Heart Failure [MeSH]”, “Randomized Controlled Trial [Publication Type]” were applied as search terms and free words were used according to the characteristics of each database. The detailed search strategy was shown in Additional file 1.

Study selection

Two reviewers (JY H and RJ Q) independently selected the eligible studies, first through title and abstract and afterwards through the full text. Any disagreements of the selection period were discussed, and if the discussion could not resolve the problem, we consulted the third author (M L) and reached consensus.

Data collection process and data items

Reviewers JY H and CY L independently extracted information of the studies using a standardized data extraction form including the first author, year of publication, disease type, sample size, interventions in the treatment and control group and outcome measures.

Risk of bias in individual studies

We used the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.1.0 [12] to assess the risk of bias of the included RCTs. Two reviewers (JY H and RJ Q) individually assessed the risk of bias and if there existed any disagreements, we resolved it through discussion with a third author (HC S).

Summary measures

We calculated the reporting rate of each outcome measure in the included RCTs and conducted comparative analysis with that in the CSRs of CHF. On account of the aim to analyze outcome measures, we did not synthesize data of the trials nor conduct a meta-analysis.

Additional analyses

Two authors (JY H, RJ Q) independently evaluated the reporting quality of outcome measures in the included RCTs based on the Management of Otitis Media with Effusion in Cleft Palate (MOMENT) criteria [13], considering the following 6 items:

-

1)

Is the primary outcome clearly stated?

-

2)

Is the primary outcome clearly defined so that another researcher would be able to reproduce its measurement? Where appropriate, this should include clear descriptions of time points, the person measuring the outcome, how the outcome was measured (for example, tools and methods used) and where the outcome was measured.

-

3)

Are the secondary outcomes clearly stated?

-

4)

Are the secondary outcomes clearly defined?

-

5)

Do the authors explain the use of the outcomes they have selected?

-

6)

Are methods used to enhance the quality of outcome measurement (for example, repeated measurement, training) if appropriate?

Results

Study selection

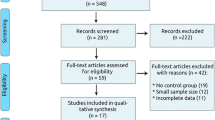

We identified 1910 records from the seven databases. Firstly we excluded 171 duplicated records and 1023 records through titles and abstracts. Then 679 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and 648 articles were eliminated for the reasons shown in Fig. 1. Finally, we included and analyzed 31 RCTs [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] in the review. We also screened sixteen CSRs of CHF [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60].

Study characteristics

Thirty-one included studies were all conducted in China and 29 were published in Chinese, two were published in English [39, 40]. The main information of each study is shown in Table 1 and the information of 16 CSRs of CHF in Table 2.

Risk of bias within studies

Among the 31 RCTs, only seven studies [21, 28, 30, 39, 40, 43, 44] used “random number table” or statistical software to generate the random sequence, the others just mentioned “random” but no description of specific methods. Two studies [39, 40] described allocation concealment and the blinding methods. Three studies [30, 39, 40] reported the case abscission and withdrawal. Generally, the risk of bias within the included RCTs was classified as high (See Fig. 2).

Results of individual studies

Reporting of outcome measures

Outcome measures in the included RCTs differed. As the end points of CHF, mortality and rehospitalization were only reported by 4 studies (4/31, 12.90%), the other studies all reported surrogate outcomes, including efficacy of cardiac function (83.87%), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)(54.84%), 6 min’ walk distance (6MWD)(45.16%) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP)(16.13%). No studies reported related cardiovascular events. Seventeen studies (17/31, 54.84%) reported adverse drug reactions (ADRs), while 14 studies (14/31, 45.16%) did not report any safety measures.

By contrast, all of the CSRs of CHF reported all-cause mortality (16/16, 100%), focused on the end points and safety measures and analyzed the all-cause and specific-cause mortality or hospitalization respectively. The overall reporting of outcome measures is shown in Table 3 and Fig. 3.

Additional analysis

Reporting quality of outcome measures

All 31 RCTs reported the specific definition of outcomes, while only two [39, 40] clearly stated the primary and secondary outcome measures which were considered as high reporting quality of outcomes. Eight studies [14, 17, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 41] explained the use of the outcomes they had reported and five [19, 21, 23, 28, 40] adopted methods to enhance the quality of the outcome measurement, including training the investigators and arranging executives to measure the outcomes. Tables 4 and 5 shows the assessment of outcome reporting quality [13].

Discussion

This systematic review mainly analyzed outcome measures in RCTs which assessed the efficacy of TCM in treating CHF caused by CHD. We included 31 trials meeting the eligibility criteria and extracted outcome measures from these studies. The outcome measures were mortality, rehospitalization, efficacy of cardiac function, LVEF, 6MWD and BNP, of which mortality and rehospitalization are end points for patients with CHF while the others are surrogate outcomes [61]. Only four studies (4/31, 12.90%) reported mortality or rehospitalization, and in comparison, all 16 CSRs of CHF analyzed all-cause mortality. This difference indicated that present TCM trials mostly assessed the surrogate outcomes and lacked evaluation of CHF end points.

In this review, nearly half of the included studies (14/31, 45.16%) did not mention any ADRs or adverse events, which apparently affected the safety assessment.

Apart from the problems of selecting outcome measures, the reporting quality of outcome measures was generally low, twenty-nine (93.55%) trials did not define the primary and secondary outcomes, which would confuse readers about major objectives of the trials and what the interventions really can improve.

In terms of methodology of the included RCTs, there were only two RCTs [39, 40] considered as high-quality. In general, the risk of bias of these trials was classified as high. We considered that the design and implementation of most studies were far away from an optimal RCT in random sequence, allocation concealment, blinding, statistics and reporting.

The selection of outcome measures is a critically important step in clinical trials. Scientifically rigorous outcomes could show significant and comprehensive information about the efficacy and safety of specific intervention [62], which would produce positive impact on clinical choices and decisions for physicians. In large-scale trials of heart failure, end points like mortality and hospitalization, were mostly set as primary outcomes [63, 64] and treatments that could reduce mortality or morbidity would be recommended in influential clinical guidelines [65, 66]. We did comparative analysis with CSRs, which are commonly agreed as high-quality information for making health decisions, to identify the present problems with outcome measures in studies conducted by TCM researchers. It was found that evaluation of improving clinical symptoms without robust evidence of clinical end points might be the primary reason why TCM interventions have not been widely recognized [67].

A European Society of Cardiology (ESC) consensus on the outcomes of HF trials [61], which was included in the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) database, highlighted that clinical end points could support the consolidation of therapeutic strategies. Whilst surrogate outcomes reflecting manifestations are typically applied in earlier phases of drug or device development to support proof-of-concept (Fig. 4). We recommended that the future TCM trials could refer to this consensus to select outcome measures.

Schematic of outcomes for chronic heart failure trials [61]

The assessment of safety is indispensable for any clinical trial. In the included RCTs, CHF patients secondary to CHD, mostly hade one or more comorbid conditions that would potentially cause treatment conflict [68]. Researchers should attach great importance to ADRs, adverse events or other safety outcomes throughout the studies and have the responsibility to estimate whether the intervention has a negative impact on patients or aggravates heart failure subsequently affecting mortality or hospitalization [69]. It is strongly recommended that TCM researchers should pay enough attention to the evaluation and reporting of safety in each trial.

Through this review, we proposed that TCM clinical trials should focus on the assessment of clinical endpoints when evaluating TCM interventions in treating CHF. Whereas, we were aware that the included trials were all too small to assess clinical endpoints. Whether the quantity of participants, the duration of the trial or the involved areas, these trials cannot be regarded as large-scale trials. The shortest duration of the included trials was 1 week [39] in which it seemed to be impossible to record mortality, rehospitalization or other endpoints. Actually, there might be difference of the endpoints between treatment and control group when the follow-up time was longer than or equal to 6 months in clinical trials [20, 22].

It is indeed difficult to conduct a TCM trial with certain size and duration to evaluate endpoints of heart failure, which would need appropriate organization and funding. We need high-quality prospective, multicenter RCTs [11, 70] rather than the present repetitive trials within a limited scale to promote the benign development of TCM [71]. We recommend collaboration among hospitals, research institutes and enterprises of TCM to conduct multicenter clinical trials to assess endpoints and generate convincing evidence which could guide the TCM clinical practice in a real sense.

This review has several limitations. First, Thirty-one trials might not be enough to analyze various outcome measures. Second, neither our review nor the included trials distinguished heart failure with reduced ejection fraction or preserved ejection fraction, which would affect the selection and evaluation of corresponding outcome measures. Third, the proportion and reporting quality of the outcomes we analyzed in the review cannot involve comprehensive information about outcome measures in RCTs. The methods to measure the outcomes, timing of measurement, how to enhance the quality of outcome measurement, follow-up of the primary outcomes and the assessment of composite outcomes are all significant factors discussing outcome measures and our future research will focus on these problems. Fourth, due to the aims of the review, we did not conduct meta-analysis within the 31 RCTs. In the future, we would include trials without or with low heterogeneity, comprehensively analyze outcomes and evaluate the efficacy and safety of TCM treatments.

Conclusions

Several problems with the outcomes existed in present trials of TCM in treating CHF caused by CHD, including the lack of concentration on the clinical end points of HF, adequate safety evaluation, together with the low reporting quality. Moreover, the risk of bias was classified as high. In order to produce robust and convincing evidence for TCM in treating CHF caused by CHD, further studies should be rigorous and well-designed, set clinical end points as the primary outcome measures and strengthen evaluation of safety.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials analyzed supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and the additional files.

Abbreviations

- 6MWD:

-

6 min’ walk distance

- ADRs:

-

Adverse drug reactions

- BNP:

-

Brain natriuretic peptide

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- CHF:

-

Chronic heart failure

- CSR:

-

Cochrane systematic review

- HF:

-

Heart failure

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- TCM:

-

Traditional Chinese medicine

References

Ambrosy AP, Fonarow GC, Butler J, Chioncel O, Greene SJ, Vaduganathan M, et al. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(12):1123–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.053.

Mosterd A, Hoes AW. Clinical epidemiology of heart failure. HEART. 2007;93(9):1137–46. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2003.025270.

Bleumink GS, Knetsch AM, Sturkenboom MC, Straus SM, Hofman A, Deckers JW, et al. Quantifying the heart failure epidemic: prevalence, incidence rate, lifetime risk and prognosis of heart failure the Rotterdam study. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(18):1614–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.038.

Chen W, Gao R, Liu L, et al. Summary of China cardiovascular disease report 2017.CHINESE. Circ J. 2018;01:1–8.

Roger VL, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Hellermann-Homan JP, Killian J, Yawn BP, et al. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA. 2004;292(3):344–50. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.3.344.

Levy D, Kenchaiah S, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Kupka MJ, Ho KK, et al. Long-term trends in the incidence of and survival with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(18):1397–402. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020265.

Zhang Y, Zhang J, Butler J, Yang X, Xie P, Guo D, et al. Contemporary epidemiology, management, and outcomes of patients hospitalized for heart failure in China: results from the China heart failure (China-HF) registry. J Card Fail. 2017;23(12):868–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2017.09.014.

Gerber Y, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Chamberlain AM, Manemann SM, Jiang R, et al. A contemporary appraisal of the heart failure epidemic in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2000 to 2010. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):996–1004. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0924.

Cao Y, Hu D, Wang H, et al. A survey of medical therapies for chronic heart failure in primary hospitals in China. Chin J Int Med. 2006;11:907–9.

Cheng K, Wu N. Retrospective investigation of hospitalized patients with heart failure in some parts of China in 1980, 1990and 2000. Chin J Cardiol. 2002(08):5–9.

Li X, Zhang J, Huang J, Ma A, Yang J, Li W, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study of the effects of qili qiangxin capsules in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(12):1065–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.035.

Higgins JP. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0 (updated march 2011) https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/. In: Cochrane Collaboration website.

Harman NL, Bruce IA, Callery P, Tierney S, Sharif MO, O'Brien K, et al. MOMENT--Management of Otitis Media with effusion in cleft palate: protocol for a systematic review of the literature and identification of a core outcome set using a Delphi survey. Trials. 2013;14(1):70. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-14-70.

Qi J, Yuan R, Li G, et al. Adiponectin level in patients of chronic heart failure with coronary artery disease and those treated by Qishen Yiqi dropping pill. J Shanxi Med. 2010;39(12):1624–7.

Wang D, Wang Y. Clinical observation of Qishen Yiqi dripping pills in treating heart failure in patients with coronary heart disease. Jilin Med. 2010;31(16):2418–9.

Ren L, Li B, He K. Clinical observation of 100 cases of chronic heart failure after myocardial infarction treated with Qishen Yiqi dripping pills. J Dis Mon Control. 2017;11(6):503–4.

Zhou Z, Li Y, Zhu H. Influence of Shenfu injection on C-reactive protein in patients with heart failure caused by coronary heart disease. Tianjin J Tcm. 2005;3:209–10.

Yuan C, Du S. Efficacy of Yi Qi Fu Mai injection on heart failure complicated with angina pectoris in 214 patients with coronary heart disease. Chin J New Drugs. 2012;21(15):1774–7.

Qu L, Zhang W, Wang H. Clinical observation of Sanxian Qiangxin decoction in 60 cases of coronary heart disease combined with chronic heart failure. Guangming J Chin Med. 2017;32(8):1116–8.

Zou Q, Deng G, Peng G, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of Shenqi cardiotonic decoction in treatment of heart failure caused by coronary heart disease: a report of 50 cases. Hunan J Tcm. 2012;28(6):6–9.

Cheng Y, Zhu Q, Yang J, et al. Research of Guanxinkang capsule with western medicine in treating 60 cases of chronic heart failure with coronary heart disease. TCM Res. 2012;25(7):23–5.

Gong L, Zhang Y. Study of clinical intervention of Chinese medicine for chronic heart failure. World J Int Trad Western Med. 2012;07(2):166–8.

Lu J, Lu G, Wu Y, et al. Observation of Baoyuan decoction on endothelium-dependent dilation function in heart failure patients with coronary artery disease. HEBEI J TCM. 2012;34(9):1304–6.

Gu X, Shang S, Guo R. Astragalus injection assisted in the treatment of 68 cases of congestive heart failure. Herald med. 2003;8:556–7.

Liu D, Zhao M. Observation of Jiaweilinguizhugan decoction in treating 34 cases of heart failure with coronary heart disease. Shanxi TCM. 2011;32(9):1190–2.

Zhou H, Yang J. Clinical study on Luhong pellet for angina pectoris with congestive heart failure. Chin J Int Med Cardio Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;5(4):286–8.

Lai R, Sheng X, Pan G. Clinical effect of Nuanxin capsule on heart failure of coronary heart disease and its effect on left ventricular function. J New Chin Med. 2015;47(5):32–3.

Lin N, Gao J. Clinical observation of Pingchuan Guben decoction in the treatment of 50 cases of cardiopulmonary deficiency syndrome of chronic heart failure. Hunan J TCM. 2017;33(3):44–6.

Zhao D. Effect of Sanshen Yixin decoction on left ventricular function of senile coronary heart disease patients with heart failure. J New Chin Med. 2011;43(9):11–3.

Zhang W, Lu W. Clinical study of using Yangxinshi pill treating patients with Qi deficiency blood stagnation syndrome and chronic heart failure caused by coronary heart disease. J Liaoning Univ Tcm. 2010;12(3):115–8.

Li H, Liu Y, Wang Z. Clinical study on the treatment of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction of coronary heart disease by Yiqi Shengxian formula. J Sichuan TCM. 2013;31(2):66–7.

Huang H. Clinical observation on the treatment of qi deficiency and blood stasis syndrome of heart failure with coronary heart disease by Yiqi Tongluo Lishui formula. JILIN TCM. 2006;26(1):10–1.

Yang Z, Li M, Yu L. Observation on the therapeutic effect of Chinese herbal medicine benefiting Qi for warming Yang and Activating blood circulation for inducing diuresis in treating coronary heart disease with heart failure. Guangming J Chin Med. 2016;31(13):1910–1.

Niu X, Wang X, Yang L. Effect of Yiqi nourishing yin recipe on cardiac function in patients with heart failure after myocardial infarction. China Pract Med. 2015;10(22):193–5.

Xu J. Clinical study on left ventricle diastolic dysfunction in patients with chronic heart disease ameliorated by Yi Shen Shu Xin pill. Chin J Int Med Cardio Cerebrovast Dis. 2005;3(3):198–200.

Liu H. The combination of Chinese and western medicine in the treatment of 76 cased of chronic heart failure with coronary heart disease. J Sichuan TCM. 2003;21(2):27–8.

Ma Y. Therapeutic effect of Qiangxin decoction on 68 cases of coronary heart disease cardiac failure. Hebei J TCM. 2001;23(9):651–2.

Liu Y, Wang Y, Zhao Y, et al. Effect of invigorating qi and activating blood circulation on left ventricular dysfunction of coronary heart disease. J Beijing Univ Chin Med. 1996;19(6):42–4.

Xian S, Yang Z, Lee J, Jiang Z, Ye X, Luo L, et al. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled clinical study on the efficacy and safety of Shenmai injection in patients with chronic heart failure. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;186:136–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2016.03.066.

Luo L, Wang J, Han A. Chinese herbal medicine for chronic heart failure: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Trad Chin Med Sci. 2014;1(2):98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcms.2014.11.010.

Zhang Z. Clinical observation on the treatment of integrative traditional Chinese and western medicine on severe heart failure with chronic heart disease. Guangming J Chin Med. 2018;33(4):561–3.

Zhang S, Li G, Li Y, et al. Effect of Wenxin granule combined with Betaloc on plasma NT-proBNP level in patients with coronary heart failure and ventricular failure. Acta Chin Med. 2018;5:865–9.

Wang Y, Pu K. The effect of yiqi quyu formula in treating heart failure caused by coronary heart disease and evaluation of cardiac function and the level of cytokines related to inflammation. J Emerg Trad Chin Med. 2018;27(6):1053–6.

Lv J, Zhu M. The clinical effect of adding flavor sangren decoction for treating chronic heart failure of coronary heart disease with trifocal heat syndrome. J Shanxi Tcm. 2018;5:596–8.

Guo, Pittler MH, Ernst. Hawthorn extract for treating chronic heart failure. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2008;1(1):CD005312.

Katherine N, Dipak K, WJ AE, Luis M, Alberto P, van Veldhuisen Dirk J, et al. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents foranaemia in chronic heart failure patients. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2010;65(1):CD007613.

Takeda A, Taylor S, Taylor RS, Faisal K, Henry K, Martin U. Clinical service organisation for heart failure. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2012;9(9):CD002752.

Heran BS, Musini VM, Bassett K, Taylor RS, Wright JM. Angiotensin receptor blockers for heart failure. Cochrane Db SystRev. 2012;4(4):CD003040.

Hood Jr. WB, Dans AL, Guyatt GH, Jaeschke R, McMurray JJV. Digitalis for treatment of heart failure in patients in sinusrhythm. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD002901.

Lip GYH, Shantsila E. Anticoagulation versus placebo for heart failure in sinus rhythm. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD003336.

Madmani ME, Yusuf Solaiman A, Tamr Agha K, Madmani Y, Shahrour Y, Essali A, Kadro W. Coenzyme Q10 for heart failure. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD008684.

Taylor RS, Sagar VA, Davies EJ, Simon B, Coats AJS, Hasnain D, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for heart failure.Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2014;4.

Driscoll A, Currey J, Tonkin A, Krum H. Nurse‐led titration of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, beta‐adrenergicblocking agents, and angiotensin receptor blockers for people with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2015;12:CD009889.

Inglis SC, Clark RA, Dierckx R, Prieto‐Merino D, Cleland JGF. Structured telephone support or non‐invasive telemonitoringfor patients with heart failure. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2015;10:CD007228.

Alabed S, Sabouni A, Al Dakhoul S, Bdaiwi Y, Frobel‐Mercier AK. Beta‐blockers for congestive heart failure in children.Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2016;1:CD007037.

Fisher SA, Doree C, Mathur A, Taggart DP, Martin‐Rendon E. Stem cell therapy for chronic ischaemic heart disease andcongestive heart failure. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD007888.

Martí‐Carvajal AJ, Kwong JSW. Pharmacological interventions for treating heart failure in patients with Chagascardiomyopathy. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2016;7:CD009077.

Julie M, Heneghan CJ, Rafael P, Clements AM, Glasziou PP, Kearley KE, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide-guided treatment for heart failure. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD008966.

Shantsila E, Lip GYH. Antiplatelet versus anticoagulation treatment for patients with heart failure in sinus rhythm. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD003333.

Martin N, Manoharan K, Thomas J, Davies C, Lumbers RT. Beta‐blockers and inhibitors of the renin‐angiotensin aldosteronesystem for chronic heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Cochrane Db Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD012721.

Zannad F, Garcia AA, Anker SD, Armstrong PW, Calvo G, Cleland JG, et al. Clinical outcome endpoints in heart failure trials: a European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Association consensus document. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(10):1082–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hft095.

Neaton JD, Gray G, Zuckerman BD, Konstam MA. Key issues in end point selection for heart failure trials: composite end points. J Card Fail. 2005;11(8):567–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.08.350.

Swedberg K, Komajda M, Bohm M, Borer JS, Ford I, Dubost-Brama A, et al. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2010;376(9744):875–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61198-1.

McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):993–1004. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1409077.

Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland J, Coats A, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(27):2129–200. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128.

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DJ, Colvin MM, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2017;136(6):e137–61. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509.

Chinese medical association cardiovascular medicine branch, Editorial board of the Chinese Journal of Cardiology. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of heart failure in China 2018. Chin J Cardiol. 2018;46(10):760–89. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3758.2018.10.004.

Caughey GE, Roughead EE, Shakib S, Vitry AI, Gilbert AL. Co-morbidity and potential treatment conflicts in elderly heart failure patients: a retrospective, cross-sectional study of administrative claims data. Drugs Aging. 2011;28(7):575–81. https://doi.org/10.2165/11591090-000000000-00000.

Chang S, Newton PJ, Inglis S, Luckett T, Krum H, Macdonald P, et al. Are all outcomes in chronic heart failure rated equally? An argument for a patient-centred approach to outcome assessment. Heart Fail Rev. 2014;19(2):153–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-012-9369-0.

Liu Z, Liu Y, Xu H, He L, Chen Y, Fu L, et al. Effect of electroacupuncture on urinary leakage among women with stress urinary incontinence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(24):2493–501. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7220.

Zhang X, Tian R, Yang Z, Zhao C, Yao L, Lau C, et al. Quality assessment of clinical trial registration with traditional Chinese medicine in WHO registries. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e025218. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025218.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Olivia CHENG for editing the English language of this article.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2017YFC1700402) and the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (81725024). The corresponding author, Dr. Hongcai Shang, is the recipient of the two funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were responsible for the study design: JY H and RJ Q took part in the literature search and selection; JY H, SQ C and QQ D were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of the data; JY H, RJ Q and C Z drafted the paper; JY H, M L and CY L revised the manuscript; HC S guided the study and critically reviewed the paper; all authors approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests regarding the publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy.

Additional file 2.

PRISMA checklist.

Additional file 3.

list of excluded articles.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, J., Qiu, R., Li, C. et al. Problems with the outcome measures in randomized controlled trials of traditional Chinese medicine in treating chronic heart failure caused by coronary heart disease: a systematic review. BMC Complement Med Ther 21, 217 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-021-03378-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-021-03378-z