Abstract

Background

No previous study has investigated the association between oolong tea consumption and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), we aim to elucidate the association between oolong tea consumption and ESCC and its joint effects with a novel composite index.

Methods

In a hospital-based case-control study, 646 cases of ESCC patients and 646 sex and age matched controls were recruited. A composite index was calculated to evaluate the role of demographic characteristics and life exposure factors in ESCC. Unconditional logistic regression was used to calculate the point estimates between oolong tea consumption and risk of ESCC.

Results

No statistically significant association was found between oolong tea consumption and ESCC (OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 0.94–2.05). However, drinking hot oolong tea associated with increased risk of ESCC (OR = 1.60, 95% Cl: 1.06–2.41). Furthermore, drinking hot oolong tea increased ESCC risk in the high-risk group (composite index> 0.55) (OR = 3.14, 95% CI: 1.93–5.11), but not in the low-risk group (composite index≤0.55) (OR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.74–1.83). Drinking warm oolong tea did not influence the risk of ESCC.

Conclusions

No association between oolong tea consumption and risk of ESCC were found, however, drinking hot oolong tea significantly increased the risk of ESCC, especially in high-risk populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Esophageal cancer is one of the most prevalent malignancies throughout the world; it is the eighth most common cause of cancer and the sixth most common cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. Esophageal cancer is the fifth most common cause of cancer in China. The incidence rates (per 100,000) were 21.17 in the year 2012 [2]. Among the types of this cancer, approximately 90% of cases are esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), and 70% of these occur in China [3].

Tea is the most popularly consumed beverage in the world, and its consumption has grown in approximately 30 countries. It is classified into 3 major types: green tea (nonfermented), oolong tea (half-fermented), and black tea (fermented) [4]. Tea constituents, including polyphenols (such as epigallocatechin-3 gallate, epigallocatechin), lipids, vitamins and minerals, may act at numerous points of carcinogenesis, including cancer cell growth, apoptosis and metastasis [5, 6]. Oolong tea is one of the special teas in Fujian [7]. and it is one of the most popular beverages in Asian countries, especially in China. The degree of fermentation used for tea varies from 10 to 100%, causing differences in the active metabolites of different types of tea [8]. However, the degree of fermentation had little effect on the polyphenol contents in oolong tea. When the degree of fermentation used for oolong tea varies from 25 to 70%, the corresponding polyphenol contents only changed from 20.41 to 23.65% [8, 9]. Although there are many epidemiological studies about the association between green tea consumption and esophageal cancer [5, 10,11,12,13,14], there has been no study of the potential association between oolong tea consumption and ESCC.

Demographic characteristics (such as marital status, education level and economic status) and life exposure factors (such as tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking, hot food, pickled food, dried food, fruits and vegetables) have been identified as the major protective factors or risk factors for ESCC in previous studies [15,16,17]. For demographic characteristics and life exposure factors, William B et al. [18] indicated that only a number of those factors assess the degree of susceptibility, it was found that most candidates differed from the least predisposed by as much as a 30-fold difference in risk. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate these factors with comprehensive indicators. In ESCC, few studies have integrated these demographic characteristics and life exposure factors into a composite index, resulting in insufficient evaluation of the role of demographic characteristics and life exposure factors in ESCC.

The aim of the present study was to determine whether there is an association between oolong tea consumption and ESCC and its joint effects with a novel composite index.

Methods

Study population

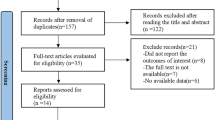

From January 2010 to December 2015, a hospital-based case-control study was conducted in Fujian Province, China. A total of 830 cases of newly diagnosed primary ESCC were recruited from the Zhangzhou Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University in Fujian. All patients were histopathologically confirmed by the World Health Organization classification of esophageal cancer (ICD-10, code-C15). Cases of second primary cancer or those with previous chemotherapy or radiotherapy were excluded. In total, 899 controls were randomly recruited from patients in the same hospital, these groups were (1) orthopedics patients; (2) neurological patients. Cases and controls were frequency-matched by sex and age (+ 5 years). Finally, a total of 646 cases and 646 controls were recruited into the study.

Data collection

Structured epidemiological questionnaires were used for collecting information from cases and controls. Detailed information including demographic information, education level, economic status (the unit of household income is Chinese yuan), tea drinking, tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking and dietary factors were collected. Tea drinking was defined as consumption of at least 1 cup of tea per week for more than 6 months. Details of tea drinking habits included the type of tea (green tea, oolong tea, black tea and other tea), the frequency of tea consumption per week (never drinking, 1–5 times/week, ≥5 times/week) and the temperature of tea (drinking hot tea refers to the intake of high temperature tea within 5 min of steeping; drinking warm tea refers to the intake of tea 5 to 12 min after steeping). Written informed consent was obtained from participants.

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics (such as marital status, education level, etc.) and life exposure factors (such as tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking, etc.) were compared with the chi-squared test. The association of tea drinking with ESCC was evaluated by using unconditional logistic regression. Odds ratios (ORs), and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to express the strength of these associations. An OR of 1.0 indicates that the distribution of exposures among cases are the same as that of controls, i.e. the exposure is not associated with the risk of ESCC. An OR greater than 1.0 indicates that exposure is positively associated with the ESCC. An OR less than 1.0 indicates that exposure might be a protective factor against the disease. When the 95% CI of the OR does not include 1.0, there is a significant association between the exposure and ESCC risk.

Two models were used for the unconditional logistic regression. Sex, age, educational level, and household income were used for adjusting the association between tea drinking and ESCC in model-1. Tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking, hot food, hard food, pickled food, fried food and fruit consumption were included in model-2 additionally. The model fit performance was evaluated according to the Akaike information criterion (AIC), and model-2 had lower AIC than model-1, indicating a better fit of model-2 over model-1.

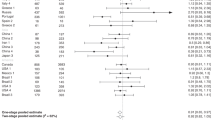

To further explore a hot tea drinking habit at a potential risk factor for ESCC, the population was divided into 3 categories, i.e., never drinks tea, warm tea drinker or hot tea drinker, and the ORs were calculated. Since it is well established that some demographic characteristics and life exposure factors are closely associated with ESCC risk, we synthesized a novel individual risk index by summing the products of statistically significant variables and corresponding multivariable-adjusted regression coefficients [19]. The population with risk indexes above the median values was coded as higher risk, while the others with indexes below the median were considered as lower risk. The higher the risk index score, the more risk factors for ESCC. A forest plot was applied to demonstrate the potential effect modification by several demographic characteristics and the risk index. I squares (I2) and corresponding Q tests (α = 0.10) were used for depicting heterogeneity. The data were analyzed by using the Stata 10 software program. All statistical tests were two-sided with the significance level at 5%.

Results

The characteristics of cases and controls are shown in Table 1. Cases and controls had similar distributions of sex, age and eating fried food (P > 0.05). However, the education level, household income, tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking, and eating hot food, hard food, pickled food and fruits were significantly different between these two groups (P < 0.05).

The relationships between tea drinking habits and ESCC are shown in Table 2. No statistically significant association was found between oolong tea consumption and ESCC (OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 0.94–2.05). Compared with those who never drink oolong tea, the OR (95% CI) was 2.23 (1.29, 3.86) for those who drink 1~5 times/week. Drinking hot oolong tea significantly increased the risk of ESCC with OR (95% Cl) of 1.60 (1.06, 2.41). Nevertheless, green tea consumption was associated with lower risk of ESCC (OR = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.26–0.71 Table 2). The inversely association with green tea drinking was also found in populations with ≥5 times/week consumption, OR (95% CI) was 0.40 (0.23, 0.69) (Table 2).

Table 3 shows the associations between demographic characteristics and life exposure factors and risk of ESCC. In terms of demographic characteristics, populations with an education level above primary and household income more than 2000 yuan/month were associated with reduced risk of ESCC, the ORs (95% CIs) were 0.33(0.22, 0.48) and 0.28(0.19, 0.41), respectively. In terms of life exposure factors, an increased risk of ESCC was found to be associated with eating hot food, eating hard food, frequently eating pickled food (≥5 times/week) and very low daily fruit consumption (≤ 5 times/week), the ORs (95% CIs) were 1.73(1.23, 2.43), 1.67(1.18, 2.37), 1.52 (1.09, 2.11) and 2.12 (1.52, 2.95), respectively. Next, we synthesized a novel individual risk index by summing the products of statistically significant variables and corresponding multivariable-adjusted regression coefficients, the risk index was classified into two categories according to the median of the population (low risk group ≤0.55, high risk group > 0.55).

The associations between the oolong tea drinking temperature and ESCC risk stratified by demographic characteristics and life exposure factors are observed in Fig. 1. An increased ESCC risk associated with oolong tea drinking temperature was detected in male, populations with household income less than 2000 yuan/month, education level not above primary, frequently eating pickled food (≥5 times/week), very low daily fruit consumption (≤ 5 times/week), but not in populations with histories of alcohol consumption, hot food or hard food intake. There was a multiplicative interaction between the temperature of oolong consumption and the risk index. The multiplicative OR (95% CI) was 1.59(1.14, 2.21), P = 0.006 (data not shown). Hot oolong tea increased the risk of ESCC only in those with high-risk indexes (OR = 1.76, 95% CI: 1.39–2.24).

The combined effect of the temperature of oolong tea drinking and the risk index group is presented in Table 4. There were no significant associations between warm oolong tea drinking and ESCC risk in the high-risk group and the low-risk group. Compared with those who did not drink warm oolong tea, odd ratios (95% CIs) were 0.70 (0.28, 1.74) for the population who drank warm oolong tea in the high-risk group and 0.63 (0.30, 1.30) for those who drank warm oolong tea in the low-risk group. Drinking hot oolong tea increased ESCC risk in the high-risk group (OR = 3.14, 95% CI:1.93–5.11). In the high-risk group, the frequency of hot oolong tea consumption 1~5 times/week and over 5 times/week significantly increased the risk of ESCC with OR (95% CIs) of 6.63 (2.26, 19.44) and 2.71 (1.63, 4.50), respectively, compared with never drinking. The duration of hot oolong consumption was significantly associated with risk of ESCC in the high-risk group. The OR was 3.16 (95% CI:1.15–8.70) for those who drank hot oolong tea 1~10 years and 3.46 (95% CI:2.03–5.91) for those who drank hot oolong tea for more than 10 years, but no significant association was found between drinking hot oolong tea and ESCC risk in the low-risk group.

Discussion

This hospital-based case-control study was conducted in southeast China to illuminate the association between oolong tea consumption and ESCC and its joint effects with a composite index. In the present study, no association between oolong tea consumption and risk of ESCC were found. Drinking hot oolong tea significantly increases the risk of ESCC, especially for high-risk populations.

Some epidemiological studies have associated the consumption of tea with a lower risk of several types of cancers, including lung, gastric, esophageal and oral cavity cancers [13, 20,21,22]. Nevertheless, most studies focused on the association of green tea consumption and the risk of cancer. The chemical composition of green tea is complex and includes polyphenols, alkaloids (caffeine and theophylline) and other undefined compounds. Among these, the major composition is tea polyphenols, including epigallocatechin-3-gallate, epigallocatechin and epicatechin gallate [23,24,25]. Studies demonstrated that the mechanisms of action of tea polyphenols include induction of apoptosis, inhibition of cell proliferation and inhibition of tumor angiogenesis [24]. In the present study, we found that green tea consumption was associated with lower risk of ESCC. Our results were consistent with the previous studies.

Oolong tea is partially fermented, and its composition is similar to that of green tea. We suspected that oolong tea has similar effects to green tea, which can reduce the risk of ESCC. Nevertheless, we did not find the association between oolong consumption and ESCC risk, which may be explained by the lower tea polyphenol content of oolong tea relative to that of green tea and the lower antioxidant activity of oolong tea compared with that of green tea [26, 27].

In this study, we also found that drinking hot oolong tea significantly increases the risk of ESCC. The underlying mechanism is that chronic thermal irritation of the esophageal mucosa might stimulate the endogenous formation of reactive nitrogen species, which may directly or indirectly induce carcinogenesis [10, 28]. It has also been hypothesized that repeated thermal injury may impair the barrier function of the esophageal epithelium, therefore, making it more vulnerable to the damage by intraluminal carcinogens [29]. Farhad et al. [30] had reported that hot tea drinking increased the risk of esophageal cancer (OR = 2.07, 95% CI: 1.28–3.35), and such risk increased for very hot tea drinkers (OR = 8.16, 95% CI = 3.93–16.0). Chen et al. [10] showed that there was a significant protective effect of green tea on esophageal cancer with low temperature tea (OR = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.29–0.97), but not for 70–79 °C and above 80 °C drinkers, with ORs and 95% CIs 2.21(1.57–5.53) and 4.74(2.67–10.51), respectively. Another study provides quantitative confirmation that “very hot” drinking temperatures are probably causally related to esophageal cancer, whereas low temperature beverages are not [31].

Does hot oolong tea drinking cause changes in oolong tea active components? Study indicated that the chemical properties of tea polyphenols changed little when heated for 60 min and 90 min below 140 °C [32]. When preparing oolong tea infusion, the boiling water temperature for making oolong tea is 100 °C. Besides, the contact time between boiling water and oolong tea is short (less than 30 s). Therefore, in the process of making oolong tea, the content of polyphenols in oolong tea is relatively stable. Drinking hot oolong tea significantly increases the risk of ESCC, the potential mechanism is that the thermal stimulation of hot oolong tea drinking, not the action of oolong active components.

Stratified by demographic characteristics and life exposure factors, we found the association between hot oolong tea drinking and ESCC risk could be modified by sex, household income, education level, pickled food and fruit consumption. Pickled food contained N-nitroso compounds, which had the potential to induce the occurrence of EC [33]. Thermal injury of hot oolong tea drinking may impair the barrier function of the esophageal epithelium, making it more vulnerable to the damage by N-nitroso compounds. In contrast, there is overwhelming evidence that fruits were inversely associated with ESCC [34], which may attribute to their contents of carotenoids, vitamin A, vitamin C, and other antioxidants [35]. In the previous study, a similar effect was also reported by a cohort study that showed high temperature tea drinking and esophageal cancer risk was dependent on smoking and alcohol drinking; there was no such association in the absence of both habits [36]. Although some previous studies have discussed the roles of demographic characteristics and life exposure factors in ESCC, few have clarified the combined effect of these factors. To overcome this deficiency, we synthesized a novel individual risk index in this study. We found that drinking hot oolong tea increased ESCC risk only in the high-risk group, there was no statistically significant association between drinking warm oolong tea and the risk of ESCC in either the high-risk group or the low-risk group. The result showed that the hot oolong tea drinking and high-risk index might interact with each other and synergistically increase the risk of ESCC. We suggest that abstaining from hot oolong tea consumption might be beneficial for preventing ESCC in high-risk populations.

Several limitations should be considered in our study. First, selection bias may exist in any hospital-based case-control study. However, all subjects were recruited from the same hospital according to strict criteria, which may minimize the selection bias. The study data were obtained from interviews and might lead to recall bias. However, the definitions of variables were clearly given in our survey. As oolong tea consumption is a long-term personal habit, recall bias is relatively low. In addition, we used well-trained investigators in data collection to avoid information bias. Finally, although the fermentation time of oolong tea in different types, the Tie Guanyin of this study mainly comes from Anxi County (Fujian Province, China), which makes little variability in constituents of different oolong teas.

Conclusions

No statistically significant association between oolong tea consumption and ESCC, but drinking hot oolong tea significantly increased the risk of ESCC, especially for high-risk populations. Our study suggests that abstaining from hot oolong tea consumption might be beneficial for preventing ESCC in high-risk populations.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 95% CIs:

-

Corresponding 95% confidence intervals

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criterion

- ESCC:

-

Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- ORs:

-

Odds ratios

References

Fitzmaurice C, Dicker D, Pain A, Hamavid H, Moradilakeh M, Maclntyre M, et al. The Global Burden of Cancer 2013 Global burden of disease Cancer collaboration. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:505–27.

Zuo TT, Zheng RS, Zeng HM, Zhang SW, Chen WQ, He J. Incidence and trend analysis of esophageal cancer in China. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2016;38:703–8.

Tang WR, Chen ZJ, Lin K, Su M, Au WW. Development of esophageal cancer in Chaoshan region, China: association with environmental, genetic and cultural factors. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2015;218:12–8.

Zheng J, Yang J, Fu Y, Huang T, Huang Y. Effects of green tea, black tea, and coffee consumption on the risk of esophageal Cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Cancer. 2013;65:1–16.

Zheng P, Zheng HM, Deng XM, Zhang YD. Green tea consumption and risk of esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:1–10.

Khan N, Mukhtar H. Tea polyphenols in promotion of human health. Nutrients. 2018;11(1):1–16.

Guo Y. Oolong tea in China[J]. Int J Tea Sci. 2012;8(2):23–24.

Gao H, Huang Z, Li H. Comparative study on the content of tea Polypheonls of sixteen kinds of China tea. Food Res Dev. 2016;37(7):33–6.

Zhu J, Chen F, Wang L, Niu Y, Yu D, Shu C, et al. Comparison of aroma-active volatiles in oolong tea infusions using GC–Olfactometry, GC–FPD, and GC–MS. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63(34):7499–510.

Chen Z, Chen Q, Xia H, Lin J. Green tea drinking habits and esophageal cancer in southern China: a case-control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:229–33.

Li XS, Chang B, Li XH. Green tea consumption and risk of esophageal Cancer: a meta-analysis of published epidemiological studies. Nutr Cancer. 2013;65:802–12.

Wang JM, Xu B, Rao JY, Shen HB, Xue HC, Jiang QW. Diet habits, alcohol drinking, tobacco smoking, green tea drinking, and the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in the Chinese population. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:171–6.

Zamoraros R, Lujánbarroso L, Buenodemesquita HB, Dik VK, Boeing H, Steffen A, et al. Tea and coffee consumption and risk of esophageal cancer: the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition study. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1470–9.

Wu M, Liu AM, Kampman E, Zhang ZF, Veer PVT, Wu DL, et al. Green tea drinking, high tea temperature and esophageal cancer in high- and low-risk areas of Jiangsu Province, China: a population-based case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1907–13.

Lagergren J, Andersson G, Talbäck M, Drefahl S, Bihagen E, Härkönen J, et al. Marital status, education, and income in relation to the risk of esophageal and gastric cancer by histological type and site. Cancer. 2016;122:207–12.

Dong J, Thrift AP. Alcohol, smoking and risk of oesophago-gastric cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31(5):509–17.

Abnet CC, Arnold M, Wei WQ. Epidemiology of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2017;154(2):360–73.

Kannel WB, Castelli WP, Mcnamara PM. The coronary profile: 12-year follow-up in the Framingham study. J Occup Med Official Publ Ind Med Assoc. 1967;9:611–9.

Balkau B, Hu G, Qiao Q, Tuomilehto J, Borchjohnsen K, Pyörälä K. Prediction of the risk of cardiovascular mortality using a score that includes glucose as a risk factor. The DECODE Study. Diabetologia. 2004;47:2118–28.

Chen F, He BC, Yan LJ, Liu FP, Huang JF, Hu ZJ, et al. Tea consumption and its interactions with tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking on oral cancer in Southeast China. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71:481–5.

Wang L, Zhang X, Liu J, Shen L, Li Z. Tea consumption and lung cancer risk: a meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies. Nutrition. 2014;30:1122–7.

Inoue M, Sasazuki S, Wakai K, Suzuki T, Matsuo K, Shimazu T, et al. Green tea consumption and gastric cancer in Japanese: a pooled analysis of six cohort studies. Gut. 2009;58:1323–32.

Koca İ, Bostancı Ş. Production, composition, and health effects of oolong tea. Turk J Agric Food Sci Technol. 2014;2:1935–46.

Cabrera C, Rafael GA, López MC. Determination of tea components with antioxidant activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:4427–35.

Nechuta S, Shu XO, Li HL, Yang G, Ji BT, Xiang YB, et al. Prospective cohort study of tea consumption and risk of digestive system cancers: results from the Shanghai Women's health study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:1056–63.

Zhang G, Miura Y, Yagasaki K. Effects of green, oolong and black teas and related components on the proliferation and invasion of hepatoma cells in culture. Cytotechnology. 1999;31:37–44.

Satoh E, Tohyama N, Nishimura M. Comparison of the antioxidant activity of roasted tea with green, oolong, and black teas. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2005;56:551–9.

Ghadirian P. Thermal irritation and esophageal cancer in northern Iran. Cancer. 1987;60:1909–14.

Tang L, Xu F, Zhang T, Lei J, Binns CW, Lee AH. High temperature of food and beverage intake increases the risk of oesophageal cancer in Xinjiang, China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:5085–8.

Islami F, Pourshams A, Nasrollahzadeh D, Kamangar F, Fahimi S, Shakeri R, et al. Tea drinking habits and oesophageal cancer in a high risk area in northern Iran: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2009;338:876–9.

Okaru AO, Rullmann A, Farah A, Gonzalez EDM, Stern MC, Lachenmeier DW. Comparative oesophageal cancer risk assessment of hot beverage consumption (coffee, mate and tea): the margin of exposure of PAH vs very hot temperatures. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:236–48.

Xu W, Wang L, Ning N. The Innuence of different heating temperatures and heating times on loss rate of tea polyphenols. Chin Agric Sci Bull. 2009;25(02):6–8.

Tan HZ, Lin WJ, Huang JQ, Dai M, Fu JH, Huang QH, et al. Updated incidence rates and risk factors of esophageal cancer in Nan ao island, a coastal high-risk area in southern China. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30(1):1–7.

Freedman ND, Park Y, Subar AF, Hollenbeck AR, Leitzmann MF, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and esophageal cancer in a large prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2753–60.

Harasym J, Oledzki R. Effect of fruit and vegetable antioxidants on total antioxidant capacity of blood plasma. Nutrition. 2014;30:511–7.

Yu C, Tang H, Guo Y, Bian Z, Yang L, Chen Y, et al. Effect of hot tea consumption and its interactions with alcohol and tobacco use on the risk for esophageal Cancer: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:489–97.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful thank to the Zhangzhou Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University for data collection.

Funding

Funding was obtained from the National Key R&D Program of China (No.2017YFC0907100), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (No. 2015 J01305), Medical Innovation project of Fujian Province (No.2018-CX-38) and the Startup Fund for scientific research, Fujian Medical University (No. 2018QH2012). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HZJ conceived of the study, participated in its design and reviewed the manuscript. LS and LZ designed the study, performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. HF and PXE performed drafted the manuscript. HLP, LYF, LWT, YHM, XZS and ZHH carried out the clinical sample collection and drafted the part of manuscript. CHL, CWL, HRG performed pathological evaluation and interpretation of all samples included in the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from participants, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fujian Medical University (number: 201495).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Lin, Z., Huang, L. et al. Oolong tea consumption and its interactions with a novel composite index on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Complement Altern Med 19, 358 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-019-2770-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-019-2770-7