Abstract

Background

Contraceptive use contributes to improved maternal and child health, education, empowerment of women, slow population growth, and economic development. The role of the family in influencing women’s health and health-seeking behavior is undergoing significant changes, owing to higher education, media exposure, and numerous government initiatives, in addition to women’s enhanced agency across South Asia. Against this backdrop, this study assesses the relationship between women’s living arrangements and contraceptive methods used in selected south Asian countries (India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh).

Methods

Data of currently married women aged 15–49 from the recent round of Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) of four South Asian countries, i.e., Nepal (2016), Pakistan (2017–18), Bangladesh (2017–18), and India (2019–21) had been used. Bivariate and multinomial logistic regression was performed using Stata with a 5% significance level.

Results

Living arrangement of women had a significant association with contraceptive use in South Asia. The Mother-in-law (MIL) influenced the contraceptive method used by the Daughter-in-law (DIL), albeit a country-specific method choice. Modern limiting methods were significantly higher among women living with MIL in India. The use of the modern spacing method was considerably high among women co-residing with husband and/or unmarried child(ren) and MIL in Nepal and India. In Bangladesh, women living with husband and other family member including MIL were more likely to use modern spacing methods.. Women co-residing with the MIL had a higher likelihood of using any traditional contraceptive method in India.

Conclusions

The study suggests family planning program to cover MIL for enhancing their understanding on the benefits of contraceptive use and modifying norms around fertility. Strengthening the interaction between the grassroots level health workers and the MIL, enhancing social network of DIL may help informed choice and enhance the use of modern spacing methods. Women’s family planning demands met with modern contraception, and informed contraceptive choices, must also be achieved to reach the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Contraceptive use contributes to improved maternal and child health, education, empowerment of women, slow population growth, and economic development [1, 2]. Nevertheless, in South Asia, the use of modern contraception is still deficient, with an overall median contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR) of 37%. The unmet need for contraception is as high as 12% in the South Asian region [3]. Several dimensions of factors, i.e., individual characteristics (education, economic status, race, ethnicity, place of residence, religion, occupation), demographic factors (age, sex, parity), relationship characteristics (partnership types, communication, attitude), family or household characteristics (family structure, co-residence, household economy, division of labor), and community characteristics (cultural, social and political context) affect the sexual health of women including family planning [4]. Recent literature suggests that women’s age, education, place of residence, and region are the significant determinants of contraceptive use in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan [5,6,7,8]. Women’s occupation, body mass index, breastfeeding practice, husband’s education, wish for children, sexual activity in the past year, abstaining status, the number of children born in the last 5 years, and the total number of children ever died are significantly associated with contraceptive use in Bangladesh [5]. Social groups and the number of surviving sons are crucial factors of contraception use in India [8]. A strong positive impact of spousal communication on contraceptive use is found in Nepal [9]. The economic condition of women has been identified as a significant determinant of contraceptive use in India and Pakistan [6, 8].

Several studies have explored the individual determinants of contraceptive use, but very few have attempted to understand the relationship of contraceptive use with women’s living arrangements. The presence of a modern contraceptive user in the household positively influences the use of modern contraceptives among young married women [10]. The presence of mother-in-law (MIL) is found to be a significant influencer of contraceptive use of daughter-in-law (DIL) in South Asia [11]. Country-specific studies also indicate the contributory role of MIL in the reproductive health of the DIL, including contraception, such as in India [12,13,14], Pakistan [15, 16], Nepal [17] and Bangladesh [18]. In India, the MIL influences the modern-limiting method of contraception use of DIL but not of the modern spacing method of contraception use [13]. In Bangladesh, contraceptive use is high for a DIL with a MIL who supports contraceptive use [19].

The MIL influences DIL’s use of contraception sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly through her son [20] and sometimes by controlling the mobility [21] of DIL as well as restricting her from creating any peer group [12]. There again exist contradictory results in respect of modern contraceptive use of DIL by the presence or absence of MIL; some studies found the latter as a barrier [22] and some as a facilitator [13, 16, 23]. However, most of these past studies are (a) based on relatively smaller sample sizes, (b) do not represent the national scenario (c) focus only on modern methods without segregating limiting and spacing methods. South Asian societies are witnessing changes, as evident in the increased female education and work participation in secondary or tertiary sectors, the rise of youth culture that shapes the experience of new intimacies, amendments, and the enactment of new laws aimed at women empowerment [24]. Therefore, South Asia’s patriarchal family system is also compelled to adjust its norms and values. The role of the family in influencing women’s health and health-seeking behavior is, thus, undergoing significant changes, owing to higher education, media exposure, and numerous government initiatives, in addition to women’s enhanced agency across South Asia [24,25,26]. Against this backdrop, this study assesses the relationship between women’s living arrangements and contraceptive methods used in selected south Asian countries-India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh.

Methods

Data

The most recent Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data for four selected countries, i.e., Nepal (2016), Pakistan (2017–18), Bangladesh (2017–18), and India (2019–21), were used for the analysis. DHSs are nationally representative large-scale cross-sectional surveys that provide data on various health indicators, including contraceptive use. DHS sample designs are usually two-stage probability samples drawn from the most recent sample frame. The Indian DHS comprises two modules of questions, i.e., State and District modules. The sample of women covered in the state module is a subsample (15%) of the district module. Questions on husbands’ backgrounds and women’s work, women’s empowerment, HIV/AIDS, and domestic violence were administered to women in the state module only. However, DHS of remaining three countries contains only one module of questions representing the country. Informed consent procedures were followed in the DHSs, and only those who agreed voluntarily were interviewed. The surveys were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the involved Institutes, and the datasets are freely available at https://www.dhsprogram.com. More details about DHS survey design, sampling, survey instruments, data collection procedure, and ethical considerations are present here [27]. The analysis was carried out for currently married women aged 15–49 in the selected countries, i.e., Bangladesh (n = 18,895), Nepal (9,897), Pakistan (11,902), and India (5,12,408).

Outcome variable

The outcome variable used in this study was ‘contraceptive method use’; classified as not using any method, modern spacing methods, modern limiting methods, and any traditional method. Modern spacing methods include Pill, IUD, injections, diaphragm, condom, foam or jelly, lactational amenorrhea, and standard days. Female and male sterilization was considered a modern limiting method. Rhythm/ periodic abstinence and withdrawal were regarded as the traditional contraceptive methods.

Predictor variables

The household living arrangement of the women was the primary predictor variable for this analysis. It was categorized as (1) Living with a husband and/or unmarried children: defined as households comprised of a married couple or a man or a woman living alone or with unmarried children with or without unrelated individuals; (2) Living with a husband and other family members except MIL: defined as households comprised of a married couple and other family members except MIL; (3) Living with husband and other family members including MIL: defined as household comprised of a married couple and other family members including the MIL, and (4), Living with a husband and/or unmarried children and MIL: defined as households comprised of a married couple or a man or a woman living alone or with unmarried children with or without unrelated individuals and with MIL.

To assess the adjusted effect of household living arrangements on contraceptive use, selected socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the women such as current age (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44, 45–49), years of schooling (no schooling, less than 10 years, 10 and more years), desire for more children (no, yes, undecided), gender of living children (have only daughters, have at least one son), mass-media exposure (yes, no), wealth quintile (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, richest), religion (Hindu, Muslim, others-except for Pakistan), place of residence (rural, urban), geographical region were also included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Univariate analysis was carried out to understand the profile of the study sample. Bivariate analysis was conducted to understand the individual association between the predictors and outcome variables. Multinomial logistic regression was used to check the adjusted effects of the predictor variables on contraceptive method use. The regression model used “not using any method” as the reference category. The predictor variables included for regression analysis were finalized after checking multicollinearity through the Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) test. Weights were used to restore the sample’s representativeness. The analyses were done with Stata (version 16) with a 5% significance level.

Results

Sample characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 presents the socioeconomic and demographic profile of the currently married women aged 15–49 in Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, and Nepal. Of the total women covered in the study, a majority were living in households with a husband and/or unmarried child(ren) in India (49%), Bangladesh (56%), and Nepal (48%). In Pakistan, most (45%) women lived in households with husbands and other family members except MIL. Most women had no schooling in Nepal (41%) and Pakistan (49%). The majority of women had no more desire for children in all four countries, i.e., India (74%), Nepal (73%), Bangladesh (64%), and Pakistan (47%). Close to three-fourths of women in all four countries had at least one living son, i.e., India (74%), Nepal (73%), Pakistan (73%), and Bangladesh (70%). India (82%) and Nepal (87%) had a majority of women of the Hindu religion, whereas, in Bangladesh, most (90%) followed Islam. In all four countries, the majority of women lived in rural areas, i.e., Bangladesh (64%), India (74%), Pakistan (73%), and Nepal (73%). Two-thirds of the women of Bangladesh (66%) and Pakistan (66%) had mass-media exposure. The corresponding figures were 76% in India and 82% in Nepal.

Current contraceptives use by household living arrangements and socio-demographic factors

Tables 3 and 4 presents the current use of contraceptive methods among currently married women aged 15–49 in Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, and Nepal by living arrangements of women and other socio-demographic characteristics. In Bangladesh, the use of the contraceptive method was 66% among women living with husbands and/or unmarried children, 52% for women living with husbands and other family members excluding MIL, 67% for women living with husbands and other family members, including MIL, and 65% for women living with husbands and/or unmarried children and MIL. The corresponding figures were- 40%, 28%, 34%, and 41% in Pakistan; 71%, 61%, 69%, and 71% in India; and 58%, 45%, 60%, and 67% in Nepal.

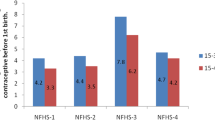

Modern spacing method use varied by household living arrangements of women across the four selected south Asian countries. The prevalence of modern spacing method use was higher among women from households with a MIL except other family members than those residing in other types of households in all countries except India. For example- in Bangladesh, 55% of those from households with a MIL except other family members were using any modern spacing method and 54% of those from households with a MIL and with other family members were using any modern spacing method, which was 38% among women from households without the MIL, 49% for women living in households comprising husbands and/or unmarried children. Across the countries, the use of modern limiting methods of contraception was the highest among women living in households comprising husbands and/or unmarried children only than their counterparts from households with/without MIL. Between the women from households with and without MIL, modern method use was considerably higher among those from households with MIL. The result is true, except for Bangladesh, where modern limiting method use was almost the same (4.6%-4.7%) for women from households with/without the MIL. No specific pattern emerged so far as the use of traditional contraception methods was concerned, ranging between 7–11% for women with different living arrangements in Bangladesh, India, and Nepal. In Pakistan, 3% of the women from households with a MIL except other family members and 7% of the women from households with a MIL including other family members were using any traditional contraceptive method, which was 11% for women living in households comprising husbands and/or unmarried children.

Across the countries, the use of modern limiting methods increased with the increasing age of women. However, a higher prevalence of modern spacing methods was noticed for women aged 20–34, after which it declined. In all four countries, the years of schooling of women were positively associated with the use of the modern spacing method and inversely with the use of the modern limiting method. Higher percentages of the women with at least one surviving son were using any modern limiting method than those with only surviving daughters. Higher percentages of the women with mass-media exposure were using any modern spacing and limiting method of contraception in all four countries compared to those without mass-media exposure. The only exception was the use of modern limiting methods in Nepal. With the increasing wealth status of women, the use of the modern spacing method of contraception increased in India and Pakistan. Again, except in Pakistan, the use of modern limiting methods decreased with increasing wealth status. Contraceptive use pattern further varied by geographic region in all four selected countries. A sizable percentage of the women not desiring more children were not using any contraceptive methods across the four countries.

Determinants of current use of contraceptive methods

Table 5 presents the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of logistic regression of factors affecting the current use of contraceptive methods. In Nepal, the odds of using modern spacing methods of contraception were significantly higher among women living with husband and/or unmarried children and MIL (OR = 2.35, CI = 1.53–3.60) as well as those living with husband and other family members, including MIL (OR = 1.63, CI = 1.32–2.02) than those women living with only husband and/or unmarried children. Similarly, the women co-residing with husband and other family member including MIL had higher probability of using any modern spacing method than their counterparts co-residing with only husband and/or unmarried children in Bangladesh (OR = 1.17, CI = 1.05–1.31). The chances of using any modern spacing methods of contraception were significantly higher among the women living in households including husband and/or unmarried children and MIL (OR = 1.12, CI = 1.05–1.18) than their counterparts living in households with only a husband and/or unmarried child(ren) in India. The chances of using any modern limiting methods of contraception were significantly higher among the women living in households including husband and/or unmarried children and MIL (OR = 1.20, CI = 1.13–1.27) as well as households including husband and other family members including MIL (OR = 1.12, CI = 1.09–1.16) than their counterparts living in households with only a husband and/or unmarried child(ren) only in India. As against the women from households with husbands and/or unmarried children, those living in households with husband and/or unmarried children and MIL (OR = 1.13, CI = 1.06–1.21) as well as with husband and other members including MIL (OR = 1.07, CI = 1.03–1.11) had higher odds of using any traditional method of contraception in India.

Compared to the women living in households comprising husband and/or unmarried child(ren), those from the households comprising husband and other household members excluding MIL had lower odds of using any modern limiting or spacing contraceptive method and any traditional method in all four countries. For example- the women living with a husband and other family members excluding MIL in Bangladesh, had a 30% (OR = 0.70, CI = 0.65–0.76) lesser chance of using any modern spacing method than those staying in households comprising a husband and/or unmarried children. The corresponding figures were 21% (OR = 0.79, CI = 0.70–0.89) for Nepal, 17% for Pakistan (OR = 0.83, CI = 0.75–0.93), and 8% (OR = 0.92, CI = 0.90–0.93) for India.

Similarly, the probability of modern limiting method use was significantly low among women living in households comprising husbands and other family members, excluding the MIL in Bangladesh (OR = 0.81, CI = 0.69–0.94), and India (OR = 0.87, CI = 0.85–0.88). Again, the odds of using any traditional method were significantly low among women living with husband and other family members excluding MIL than those living with husband and/or unmarried child (ren) in Bangladesh (OR = 0.82, CI = 0.73–0.92) and India (OR = 0.92, CI = 0.90–0.94).

Across the countries, the likelihood of using modern spacing and traditional method increased whereas chances of using modern limiting method decreased with increasing years of schooling. The probability of using modern spacing and any traditional contraceptive method was less among those who desire for additional child compared to their counterpart who desire for no more children in all studied countries. Compared to those who had only daughters, those with at least one son had higher likelihood of using any modern as well as traditional contraceptives. The chances to use of any modern as well as traditional contraceptives was higher among women with mass-media exposure than their counterpart with no mass-media exposure. Muslims had less likelihood of using any (except India in modern spacing use) contraceptive method than Hindus in other three countries. In Pakistan, with increasing wealth quintile, the chances of use of all types of contraceptive increases while it decreases in Bangladesh. In Nepal, with increasing wealth quintile, the chances of use of modern limiting method increases in Nepal but in India it leads to use of modern spacing method. Compared to urban women, the chances of contraceptive use among rural women were less except for modern limiting method use in India.

Discussion

The study found that the living arrangement of women has a significant association with contraceptive use in South Asia. The MIL continues to influence the contraceptive method used by the DIL, albeit country-specific method choice. Co-residence with MIL is associated with higher use of modern spacing method, modern limiting method and traditional method in India, and modern spacing method use in Nepal and Bangladesh. In Pakistan, women living in households without the MIL are less likely to use any contraceptive method.

In Bangladesh, the use of the modern spacing method is more in a household where women live with husbands and other family members, including MIL. There are contradictory findings that have been reported in previous small-scale studies on Bangladesh. A study based on 413 interviews in two areas with different family planning program found contraception use higher among DIL if MIL is supportive [19] while a qualitative explorative study found married adolescents are less likely to use contraception if MIL is against contraception use [28]. Another study based on 4053 currently married women in Matlab Sub district found no influence of the MIL on co-resident DIL’s use of modern contraceptives [29]. In the country, the community health worker network has worked as a backbone to spread the modern spacing method [19, 30] and motivate clients to use contraceptive methods [19, 31]. The results indicate that the community health workers could strengthen the supportive role of the MILs in DIL’s use of the spacing method by gaining trust of MIL through frequent home visits and intensive interactions about the advantages of use of modern spacing methods for birth spacing [19]. We found that any types of contraceptive use is significantly less among women residing in households without MIL, hence the community health worker should identify these households and make extra effort in order to increase the use of contraception among them.

In India, the use of modern limiting methods is more in households with husbands and other family members, including MIL and households with husband and/or unmarried child(ren) and MIL. The results conform to a past study based on data from an earlier round of Indian DHS [32]. Another study reveals that the MILs usually favor the modern limiting method of contraception, influence the timing of use of modern limiting method and oppose the modern spacing method in India [13]. MIL also often force their DIL to prove their fertility in the first year of their marriage, which also restrains the DIL from using any modern spacing method [11, 33]. Studies even indicate that the MIL restricts the mobility of their DIL to disconnect them from the outer world and to maintain their dominance over DIL’s reproductive choice [12, 21]. The use of modern spacing method is high in households with husband and/or unmarried child(ren) and MIL, which may be because the decision to use modern spacing method is majorly taken between husband and wife and thus, though MIL is not in favor of modern spacing method still its use is high. A past small scale qualitative study (Based on 60 MIL, 60 DIL and Sons from same family) conducted in Madhya Pradesh, India conforms this and found that DIL is not comfortable to discuss or disclose about contraceptive use with MIL but they only discuss with husband [13]. Another earlier study also reveal that husband’s decision regarding spacing method use is more important than MIL’s [34]. In the country, the use of any traditional method of contraception is also high among women co-residing with MIL. The result is also in line with a previous study, which reveals that MIL are in favor of traditional methods of contraception for spacing of births [20]. Moreover, the higher use of the traditional method of contraception may be due to less access and knowledge about the modern spacing method among less educated economically poor women or may also be among highly educated wealthy women for the wholesome side effects of the modern contraceptive methods [13, 35].

As women co-residing with MIL are more likely to use modern limiting method and traditional methods, family planning programs may be designed to enhance social networks to increase women’s access and uptake of modern spacing methods. An earlier study also highlights the beneficial role of social networks to increase women’s access and uptake of family planning methods [12]. Again, as MIL often acts as the gatekeeper, future programs may directly target them to inform her about the benefits of family planning [36]. Moreover, schemes like Saas-Bahu Sammelan (under Mission Parivar Vikas), a platform for mothers-in-law and their daughters-in-law, which attempts to influence attitudes and ideas about sexual and reproductive health through interactive games and by drawing on personal experiences, needs to be implemented throughout the country. At present this scheme is limited to only 146 high fertility districts (only for rural areas) [37]. A previous study also advocates the beneficial role of this scheme [10].

In Pakistan, contraceptive use is low among women co-residing with other family members without the MIL. Earlier studies from Pakistan also viewed that MIL significantly influences DIL’s contraception use behavior [15, 16]. Evidence further reveals that MIL have greater decision-making authority over young couples’ family planning than either member of the couple itself [38]. Nevertheless, as the overall contraception use is very low in Pakistan compared to other studied South Asian countries, there should be focus on promoting all types of modern contraceptives among women and sensitizing MIL about the benefits of contraceptives by the Lady Health Workers (LHWs) and Family Welfare Assistants (FWAs) placed under existing FP program.

In Nepal, the use of modern spacing is high in a household where women co-reside with MIL. This is in line with previous studies which found that spacing method use can be high through improved and positive spousal communication as well as MIL’s support in delaying childbearing to allow their daughter-in-law to mature, continue her education or earn wages; irrespective of societal pressure upon them [9, 39]. This contradicts to previous literature that reveal MIL as one of the barriers to contraceptive use as she pressurizes DIL to produce a child in the first year itself to prove her fertility, restricts the mobility of DIL, and decides contraceptive use for DIL [17]. Adolescent women are further more vulnerable to the MIL’s decisions on their contraceptive behavior. Nearly one-fifth of the women have unmet need for limiting [40], which has increased in recent times; which suggest the need for expanding the basket of choices in the program to address the need of the women. Additionally, promising interventions such as Sumadhur i.e., intervention for triads (wives, husbands, and mothers-in-law) including inequitable gender norms and practices, fertility planning and contraception, and couples and household relationship dynamics, which has been proved beneficial in improving fertility and family planning decision-making norms among newlyweds should be scaled up [41].

Our study found MIL enhances modern spacing method use in Bangladesh, Nepal and India (in set up with only husband and MIL), and influences higher use of modern limiting and traditional methods use in India. Though this study did not analyze whether the method used were informed choices, evidence suggests inadequate informed contraceptive choice in India [42], Bangladesh [43], Nepal [44], and Pakistan [45]. Using contraception without informed choice violates women’s reproductive rights [46]. The inadequately informed choice might lead to higher contraceptive discontinuation. High contraceptive discontinuation rates among women who discontinue use for reasons other than the desire to get pregnant lead to unintended pregnancies [47, 48]. Unintended pregnancies may lead to high maternal morbidity and mortality [49]. Contraceptive discontinuations are further linked with higher unmet needs and induced abortions [50, 51], negatively affecting women’s health.

The study found that irrespective of the studied countries, household living arrangements influence contraceptive method use- contraceptive acceptance is less among women from households with husband and other family members excluding MIL. Co-residence with MIL is associated with higher use of modern spacing method, modern limiting method, and traditional method in India, and modern spacing method use in Nepal and Bangladesh. The results suggest strengthening country-specific family planning programs to ensure informed contraceptive choices in an enabling household environment. Programs proved to improve contraceptive decision making and use among women by addressing concerns of MIL or engaging them in the program may be scaled up to enhance informed contraceptive use.. Irrespective of countries, the use of contraceptives is less among households with husbands and other family members excluding MIL. As an experienced aged female household member, MIL plays a crucial role in DIL contraceptive choice and utilizations, as contraceptives still consider a women’s subject in selected South Asian countries. So, the grassroots-level health workers should identify those households without MIL and give extra attention to them in respect of contraceptive use. This will improve the use of contraceptive use among those households.

The study has some methodological limitations. The study is based on cross-sectional data, thus, limiting any causal association between household living arrangements and contraceptive use. There is a possibility of socio-cultural and contextual factors influencing the contraceptive method use, which this study could not consider due to a lack of data. Despite these limitations, the study’s strengths are that the findings are based on large-scale, nationally representative samples chosen using a robust sampling design. Thus, the results are contemporary and relevant. The results contribute to the existing scanty evidence on the role of MIL in DIL’s contraceptive use in South Asia.

Conclusion

The study concludes that the living arrangement of the women, especially co-residence with MIL, is associated with the contraceptive method used in South Asia. The MIL continues to influence the contraceptive method used by the DIL, albeit country-specific method choice. The study suggests family planning program to cover MIL for enhancing their understanding on the benefits of contraceptive use and modifying norms around fertility. Strengthening the interaction between the grassroots level health workers and the MIL, enhancing social network of DIL may help informed choice and enhance the use of modern spacing methods. Women’s family planning demands met with modern contraception, and informed contraceptive choices, must also be achieved to reach the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the [Demographic and Health Surveys Repository] repository, (https://dhsprogram.com).

References

Levine R, Langer A, Birdsall N, Matheny G, Wright M, Bayer A. Contraception. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P, editors. Disease control priorities in developing countries. 2nd ed. Washington (DC), New York: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Pradhan MR. Contraceptive mix and informed choice. Lancet (London, England). 2022;400(10348):255–7.

Nations U. Family planning and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development (data booklet). 2019.

Blanc AK. The effect of power in sexual relationships on sexual and reproductive health: an examination of the evidence. Stud Fam Plann. 2001;32:189–213.

Hossain MB, Khan MHR, Ababneh F, Shaw JEH. Identifying factors influencing contraceptive use in Bangladesh: evidence from BDHS 2014 data. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:192.

Meherali S, Ali A, Khaliq A, Lassi ZS. Prevalence and determinants of contraception use in Pakistan: trend analysis from the Pakistan Demographic and Health Surveys (PDHS) dataset from 1990 to 2018. F1000Res. 2021;10:790.

Pokheral T, Adhikari R, Aryal MK, Gurung R, Dulal MB, Dahal MH. Socioeconomic determinants of inequalities in use of sexual and reproductive health services among currently married women in Nepal: a further analysis of NMICS 2019 and NDHS 2016. 2021.

Pradhan MR, Dwivedi LK. Changes in contraceptive use and method mix in India: 1992–92 to 2015–16. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2019;19:56–63.

Link CF. Spousal communication and contraceptive use in rural Nepal: an event history analysis. Stud Fam Plann. 2011;42:83–92.

Ranjan M, Mozumdar A, Acharya R, Mondal SK, Saggurti N. Intrahousehold influence on contraceptive use among married Indian women: evidence from the National Family Health Survey 2015–16. SSM Popul Health. 2020;11:100603.

Najafi-Sharjabad F, Zainiyah Syed Yahya S, Abdul Rahman H, HanafiahJuni M, Abdul Manaf R. Barriers of modern contraceptive practices among Asian women: a mini literature review. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5:181–92.

Anukriti S, Herrera-Almanza C, Pathak P, Karra M. Curse of the Mummy-ji: the influence of mothers-in-law on women in India. Am J Agric Econ. 2020;102(5):1328–51.

Char A, Saavala M, Kulmala T. Influence of mothers-in-law on young couples’ family planning decisions in rural India. Reprod Health Matters. 2010;18:154–62.

Kumar A, Bordone V, Muttarak R. Like mother(-in-law) like daughter? Influence of the older generation’s fertility behaviours on women’s desired family size in Bihar, India. Eur J Popul. 2016;32:629–60.

Fikree FF, Khan A, Kadir MM, Sajan F, Rahbar MH. What influences contraceptive use among young women in urban squatter settlements of Karachi, Pakistan? Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2001;27:130–6.

Kadir MM, Fikree FF, Khan A, Sajan F. Do mothers-in-law matter? Family dynamics and fertility decision-making in urban squatter settlements of Karachi, Pakistan. J Biosoc Sci. 2003;35:545–58.

Sekine K, Khadka N, Carandang RR, Ong KIC, Tamang A, Jimba M. Multilevel factors influencing contraceptive use and childbearing among adolescent girls in Bara district of Nepal: a qualitative study using the socioecological model. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e046156.

Bates LM, Maselko J, Schuler SR. Women’s education and the timing of marriage and childbearing in the next generation: evidence from rural Bangladesh. Stud Fam Plann. 2007;38:101–12.

Nosaka A, Bairagi R. Traditional roles, modern behavior: intergenerational intervention and contraception in rural Bangladesh. Hum Organ. 2008;67:407–16.

Barua A, Kurz K. Reproductive health-seeking by married adolescent girls in Maharashtra, India. Reprod Health Matters. 2001;9:53–62.

Azmat SK, Mustafa G, Hameed W, Ali M, Ahmed A, Bilgrami M. Barriers and perceptions regarding different contraceptives and family planning practices amongst men and women of reproductive age in rural Pakistan: a qualitative study. Pak J Public Health. 2012;2(1):17–23.

Speizer IS, Lance P, Verma R, Benson A. Descriptive study of the role of household type and household composition on women’s reproductive health outcomes in urban Uttar Pradesh, India. Reprod Health. 2015;12:4.

Khan MS, Hashmani FN, Ahmed O, Khan M, Ahmed S, Syed S, Qazi F. Quantitatively evaluating the effect of social barriers: a case-control study of family members’ opposition and women’s intention to use contraception in Pakistan. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2015;12:2.

Bhandari P, Titzmann F-M. Introduction. Family realities in South Asia: adaptations and resilience. South Asia Multidiscip Acad J. 2017;16:1–9.

Kaur R. Marriage and migration: citizenship and marital experience in cross-border marriages between Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Bangladesh. Econ Polit Wkly. 2012;43:78–89.

Fuller CJ, Narasimhan H. Empowerment and constraint: women, work and the family in Chennai’s software industry. In: In an outpost of the global economy. India: Routledge; 2012. p. 190–210.

Croft TN, Marshall AMJ, Allen CK, et al. Guide to DHS statistics. 2018.

Shahabuddin ASM, Nöstlinger C, Delvaux T, Sarker M, Bardají A, Brouwere VD, Broerse JEW. What influences adolescent girls’ decision-making regarding contraceptive methods use and childbearing? A qualitative exploratory study in Rangpur District, Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157664.

Varghese R. Monster-in-law? The effect of co-resident mother-in-law on the welfare of Bangladeshi daughters-in-law. Chicago: Harris School of Public Policy University of Chicago; 2001.

Rahman M, Davanzo J, Razzaque AHM. When will Bangladesh reach replacement-level fertility? The role of education and family planning services. 2002.

Nahar K, Talha TUS, Nessa A, Putra IGNE, Ratan ZA, Hosseinzadeh H. Use and acceptability of birth spacing contraceptive among multiparae in Bangladesh. Eur J Clin Med. 2021;2:36–40.

Pradhan MR, Mondal S. Contraceptive method use among women in India: does the family type matter? Biodemography Soc Biol. 2022;67:122–32.

Dixit A, Bhan N, Benmarhnia T, Reed E, Kiene S, Silverman J, Raj A. The association between early in marriage fertility pressure from in-laws’ and family planning behaviors, among married adolescent girls in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, India. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):60.

Bhan N, Sodhi C, Achyut P, Thomas EE, Gautam A, Raj A. Mother-in-law’s influence on family planning decision-making and contraceptive use: a review of evidence. 2022.

Basu AM. Ultramodern contraception. Asian Popul Stud. 2005;1(3):303–23.

Varghese R, Roy M. Coresidence with mother-in-law and maternal anemia in rural India. Soc Sci Med. 2019;226:37–46.

India MoHFW-Go: Mission Parivar Vikas guidelines.23.

Varley E. Islamic logics, reproductive rationalities: family planning in northern Pakistan. Anthropol Med. 2012;19(2):189–206.

Diamond-Smith N, Plaza N, Puri M, Dahal M, Weiser SD, Harper CC. Perceived conflicting desires to delay the first birth: a household-level exploration in Nepal. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2020;46:125.

Ministry of Health - MOH/Nepal, New ERA/Nepal, ICF. Nepal demographic and health survey 2016. Kathmandu: MOH/Nepal, New ERA, and ICF; 2017.

Mitchell A, Puri MC, Dahal M, Cornell A, Upadhyay UD, Diamond-Smith NG. Impact of Sumadhur intervention on fertility and family planning decision-making norms: a mixed methods study. Reprod Health. 2023;20(1):80.

Pradhan MR, Patel SK, Saraf AA. Informed choice in modern contraceptive method use: pattern and predictors among young women in India. J Biosoc Sci. 2020;52:846–59.

Hossain S, Sripad P, Zieman B, Roy S, Kennedy S, Hossain I, Bellows B. Measuring quality of care at the community level using the contraceptive method information index plus and client reported experience metrics in Bangladesh. J Glob Health. 2021;11:07007.

Puri MC, Moroni M, Pearson E, Pradhan E, Shah IH. Investigating the quality of family planning counselling as part of routine antenatal care and its effect on intended postpartum contraceptive method choice among women in Nepal. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):29.

Hamid S, Stephenson R. Provider and health facility influences on contraceptive adoption in urban Pakistan. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2006;32(2):71–8.

WHO. Family planning/contraception methods. 2020.

Blanc AK, Curtis SL, Croft T. Does contraceptive discontinuation matter?: quality of care and fertility consequences. 1999.

Curtis S, Evens E, Sambisa W. Contraceptive discontinuation and unintended pregnancy: an imperfect relationship. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;37:58–66.

Organization WH. Contraception: fact sheet: family planning enables people to make informed choices about their sexual and reproductive health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Casterline JB, El-Zanatay F, El-Zeini LO. Unmet need and unintended fertility: longitudinal evidence from upper Egypt. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2003;29:158–66.

Cleland J, Ali MM. Reproductive consequences of contraceptive failure in 19 developing countries. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:314–20.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Funding

The authors received no financial support from any funding agency, commercial entity, or not-for-profit organization for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. MRP: Conceptualization, Investigation; Methodology; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing; SM: Conceptualization, Data curation; Formal analysis; Software; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing. Both authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study is based on the publicly available data source, and survey agencies that conducted the field survey for the data collection have also collected a prior consent from the respondent. The NFHS-5 was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institutions involved, and the datasets are available at https://www.dhsprogram.com for broader use in social research. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. They ruled that no formal ethical consent was required to conduct research from this data source.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pradhan, M.R., Mondal, S. Examining the influence of Mother-in-law on family planning use in South Asia: insights from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan. BMC Women's Health 23, 418 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02587-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02587-7