Abstract

Background

Family planning (FP) is an effective strategy to prevent unintended pregnancies of adolescents. We aimed at identifying the socio-demographic factors underlying the low use of contraceptive methods by teenage girls in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Methods

A secondary analysis targeting teenage girls aged 15–19 was carried out on the Performance, Monitoring and Accountability project 2020 (PMA 2020) round 7 data, collected in Kinshasa and Kongo Central provinces. The dependent variable was the “use of contraceptive methods by sexually active teenage girls”, calculated as the proportion of teenagers using modern, traditional or any contraceptive methods. Independent variables were: level of education, age, province, religion, marital status, number of children, knowledge of contraceptive methods and household income. Pearson's chi-square and logistic regression tests helped to measure the relationship between variables at the alpha significance cut point of 0.05.

Results

A total of 943 teenagers were interviewed; of which 22.6, 18.1 and 19.9% used any contraceptive method respectively in Kinshasa, Kongo Central and overall. The use of modern contraceptive methods was estimated at 9.9, 13.4 and 12.0% respectively in Kinshasa, Kongo Central and overall. However, the use of traditional methods estimated at 8.0% overall, was higher in Kinshasa (12.7%) and lower (4.7%) in Kongo Central (p < .001). Some factors such as poor knowledge of contraceptive methods (aOR = 8.868; 95% CI, 2.997–26.240; p < .001); belonging to low-income households (aOR = 1.797; 95% CI, 1.099–2.940; p = .020); and living in Kongo central (aOR = 3.170; 95% CI, 1.974–5.091; p < .001) made teenagers more likely not to use any contraceptive method.

Conclusion

The progress in the use of contraceptive methods by adolescent girls is not yet sufficient in the DRC. Socio-demographic factors, such as living in rural areas, poor knowledge of FP, and low-income are preventing teenagers from using FP methods. These findings highlight the need to fight against such barriers; and to make contraceptive services available, accessible, and affordable for teenagers.

Plain English summary

The use of contraceptive methods remains low among adolescents aged 15 to 19 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. However, family planning (FP) methods can help to prevent unintended pregnancies. This study aimed at identifying the socio-demographic factors that prevent teenage girls from using FP methods. We analyzed the data from the Performance, Monitoring and Accountability project (PMA 2020), seventh round, collected in Kinshasa and Kongo Central provinces. The use of contraceptive methods by sexually active adolescents was measured according to the level of education, age, province, religion, marital status, number of children, knowledge of contraceptive methods and household income. For the 943 adolescent girls interviewed, the use of any contraceptive method was calculated at 22.6, 18.1 and 19.9%, respectively in Kinshasa, Kongo Central and overall. The use of traditional methods was estimated at 8.0% overall, higher in Kinshasa (12.7%) and lower (4.7%) in Kongo Central. However, the use of modern contraceptive methods was estimated at 9.9, 13.4 and 12.0% respectively in Kinshasa, Kongo Central and overall. Poor knowledge of contraceptive methods; low-income and living in Kongo central province were the factors associated with the low use of any contraceptive method. In conclusion, the progress in the use of contraceptive methods by adolescent girls is not yet sufficient, due to some socio-demographic barriers. These results suggest to fight against such factors; and to make contraceptive services available, accessible, and affordable for teenagers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

About half of pregnancies among adolescent women aged 15–19 living in developing countries are unintended; and more than half of these end in abortion, often under unsafe conditions [1]. Early pregnancies can have physical, emotional and socioeconomic impact in adolescent girls, families and the entire community [2, 3]. They often occur in low-income, low educated and dysfunctional families [4,5,6,7], in which alcohol consumption and early sexuality are common [8]. In the African region, teenage pregnancies are often followed by a drop out of schooling [7]; this fact is not only associated to poverty, but also makes some teenagers dependent on aid programs, and puts a considerable burden on economies and health systems [5, 6, 9].

The proportion of sexually active adolescents using contraceptive methods at age 19 is experiencing an annual increase wordwide, ranging from 2 to 17% in developing countries [10, 11]. However, the contraceptive prevalence remains low in teenagers. In 2019, 10.2% of adolescent girls were using any contraceptive method globally. In sub-Saharan Africa, the use of any contraceptive method was estimated at 10.1%, with large differences between married and unmarried adolescents [12]. Since 2006, unmet need for contraception has remained high (52%) among adolescent girls. During the same period, unmet needs in adults decreased from 45.8 to 38.0%, thus accentuating the inequalities between adults and adolescents [13]. In 12 countries, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), a study in 2019 showed that the satisfaction of demand for modern contraceptive methods remained below 10% among the adolescent group [14]. Addressing unmet need would reduce unintended pregnancies by 6.0 million per year; which means avoiding 2.1 million unplanned births, 3.2 million abortions and 5600 maternal deaths [8]. Beyond improving the availability of contraceptive methods [15], a significant number of teenagers come up against obstacles, leading to contraceptive discontinuation and failure [10, 15, 16]. Obstacles, such as unfavorable legal and social environment [3]; limited contraceptive bargaining power; low knowledge of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) can result in risky sexual behaviors [3, 16]. The majority of teenagers use unreliable sources for information on SRH [17]; and out-of-school adolescents are more vulnerable and often make less informed choices [3]. Combining demand creation and the provision of information and user-friendly services can increase the uptake contraceptive methods [5, 18], by removing bottlenecks [19,20,21].

In the DRC, although the age of majority is set at 18 [22], more than half of adolescents become sexually active at age 17. In 2017, the use of contraceptive methods by single sexually active adolescent girls was estimated at 19.1 and 16.1%, respectively for modern and traditional methods. At the same moment, the contraceptive prevalence was 9.5% for modern methods and 6.3% for traditional methods among married or unionized adolescents. Unmet need for modern contraception was estimated at 56% among adolescent girls not in a relationship [23]. In 2016, up to six in 10 pregnancies that occurred in Kinshasa were unplanned; many of them ending in unsafe abortion [24]. To improve access to and uptake of family planning (FP) methods, some innovations, such as the community distribution of contraceptives [25,26,27] have been implemented. However, they appear to have little effect on the use of contraceptive methods by adolescents. The objective of this paper was to identify the socio-demographic determinants of the low use of contraceptive methods by adolescent girls in the DRC.

Methods

In the DRC, the provision of FP services, including a range of contraceptive methods, are part of the minimum package of activities for all types of health facilities. Several approaches are used to offer contraceptive methods, including health facilities-based approaches, community-based distribution and social marketing strategy using private pharmacies. According to national Health System Strengthening Strategy (SRSS), the delivery of health care needs to be improved within health centers and hospitals.

Study design

A secondary analysis targeting adolescent girls aged 15–19 was carried out on the data of Round 7 of the Performance, Monitoring and Accountability project (PMA 2020) collected in 2018 [28]. The survey involved 3536 households, including 1854 in Kinshasa and 1682 in Kongo Central. A two-stage cluster design was used to select 110 enumeration areas (EA) in these provinces, using the selection probabilities proportional to size of the cluster. The sampling of EA and the enumeration of households were carried out before data collection. In each EA, some 33 households were selected by random sampling and all women aged 15–49 interviewed, after giving their informed consent. The sampling procedure is shown in Fig. 1.

Dependent and independent variables

Dependent variable

Through this study, FP use was first measured as overall contraceptive use, then separated into modern and traditional methods (rhythm, withdrawal and other traditional methods such as folkloric methods like amulets, herbs, etc.). For specific methods, the following hierarchy was used to tabulate current use, selecting only the highest method in the list: female sterilization, male sterilization, implants (Norplant), intrauterine device (IUD), injectables, contraceptive pills, condoms, emergency contraception, standard day method (SDM), vaginal methods (foam, jelly, suppository), lactational amenorrhea method (LAM), periodic abstinence, withdrawal, and other methods. Current use of modern contraceptive methods was defined as use of sterilization, intrauterine device, injectables, implants, pills, standard day method using CycleBeads, male and female condoms, emergency contraception, lactational amenorrhea, and spermicides) [29].

The dependent variable was “use of contraceptive methods by sexually active teenage girls”, a dichotomus variable (1 = yes; 0 = no) calculated for any, modern and traditional contraceptive methods respectively. In the context of this work, sexually active adolescents are those who reported having had sex less than a year before the data collection.

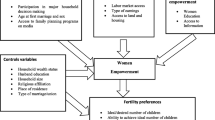

Independent variables

The independent variables were chosen in the light of the current state of knowledge of the barriers to undertake FP services and methods.. Thus, a number of socio-demographic characteristics were examined including the province of residence (Kinshasa vs Kongo Central), age of adolescent girls (15–17 vs. 18–19), level of education (high vs low), marital status (married or cohabitating _in union vs. divorced, widowed, or never married_ not in union), religion, household income, knowledge of contraceptive methods, and number of children. The level of education was considered “high” if adolescents attended at least high school and above and low for adolescents who did not finish primary school. Several religions are practiced throughout the DRC. As part of this study, we first decided to group the adolescents into three groups: none, Christian and non-Christian. However, in order to make analysis, we grouped non-Christian and none as “non-Christian” vs. “Christian”, for adolescents practicing the Christian religion. Adolescent who spontaneously cited at least three FP methods were classified as having high knowledge of contraceptive methods; those who cited less than three FP methods were ranked as “poor knowledge of FP”. Household income (household wealth) was constructed using a wealth index based on ownership of 25 household assets, house material, livestock ownership and water source, which was converted into quintiles. According to the household income, two groups of adolescent girls were formed—one group as high income corresponding to households in the 3rd, 4th and 5th wealth quintile vs the other group as low income for households in the 1st and 2nd wealth quintile. According to the number of children, women were classified in two groups: one or more children vs none.

Data collection and quality control

The data were collected by interviewers recruited from adult women living nearby and trained in data collection process, using mobile phones. They were previously validated, cleaned, weighted as part of the primary PMA study [28]. Analyzes were performed using Stata 14 software.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized as means or medians with their standard deviations or interquartile range as appropriate. The categorical variables were summarized as proportions with their confidence intervals. Bivariate analyzes were performed using Pearson's chi-square test to measure the association between dependent and independent variables taken individually. Logistic regression was performed by relating the dependent variable to independent variables pooled in a statistical model. All analyzes were performed using an alpha significance level of 0.05. Thus, all associations whose p-value was less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics consideration

The PMA 2020 surveys received approval from the ethics committees of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and the Kinshasa School of Public Health (KSPH). The research protocol for performing secondary analyzes was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the KSPH under approval number ESP/CE/027/2018. All women aged 15–49 participating to the PMA study provided written and informed consent. The need for consent to participate from parent or legal guardian was waived, for young emancipated women aged 15–17, by the ethics committee of the KSPH (approval number ESP/CE/73B/2018). In the DRC, some of these adolescents are already married or living as a couple [30,31,32].

Results

The household response rate was 95.3% for Kinshasa and 98.5% for Kongo Central. Interviews were completed with 943 adolescent girls aged 15–19. The average age of the interviewees was 16.97 ± 1.44 years old; most adolescents (58.3%) were between 15 and 17 years old. About 72.7% of respondents were in high school; 81.7% were single or never married; 66.4% lived with their parents and 84.7% had not yet given birth. Overall, about 51.2% of adolescent girls were sexually active, with the majority (62.4%) living in Kongo Central compared to 35.1% in Kinshasa (p < .001). The majority of teenagers (82.7%) were Christian, 14.2% not Christian and 3.1% did not practice any religion. About 24.9% of participants belonged to the highest economic quintile, while 15.0% came from the lowest economic quintile. Table 1

An estimated number of 188 adolescent girls used any contraceptive method. The use of any contraceptive method was therefore estimated at 19.9% across the study, which represents 22.6% in Kinshasa and 18.1% in Kongo Central; with no significant difference between these provinces (p = .089).

However, modern contraceptive methods were more used than traditional methods. The use of modern contraceptive methods was estimated at 9.9, 13.4 and 12.0% respectively in Kinshasa, in Kongo Central and overall; and no significant difference was found between these provinces (p = .100). About 8.0% of adolescent girls used traditional contraceptive methods overall. However, in Kinshasa, the use of traditional contraceptive methods was estimated at 12.7%, higher than 4.7% reported in Kongo Central (p < .001). Overall, about 18.1% of adolescent girls had unmet needs for modern contraceptive methods; representing 11.2% in Kinshasa and 22.9% in Kongo Central. Unmet needs for FP were twice as high in Kongo Central compared to Kinshasa (p < .001). (Table 2).

Six of 10 contraceptive methods used by adolescents were modern and four were traditional methods. Some adolescents used more than one contraceptive method. Thus, of all modern contraceptive methods, the foremost one used was the male condom (34.0%), followed by contraceptive pills (12.0%). The use of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods was estimated at 9.0% for implants and 1.0% for intra uterine devices (IUDs). Other modern contraceptive methods were poorly used; these are injectables (7%), emergency pill (5%), and cycle necklace (1%).

Howerever, an important number of adolescent girls used traditional contraceptive methods as their first choice. Among these contraceptive methods, the most used were rhythm methods (32.0%); followed by coitus interruptus (13.0%) Fig. 2.

Contraceptive methods used continuously over a long time are necessary to maintain the benefits in preventing unintended pregnancies. However, the data showed that 31 adolescent girls (16.5%) had stopped using FP methods at the time of the survey; mostly within the first year (data not shown); and due to several reasons. The most frequently mentioned reason was infrequent sex (42.0%), followed by early pregnancy (23.0%), high cost of contraceptives (10.0%) and desire to become pregnant (10.0%). A few numbers cited the accessibility of contraceptives methods (6.0%), side effects of contraceptives (6.0%) and partner refusal (3.0%) Fig. 3.

As for the sources of contraceptive methods for adolescents, the main source was pharmacies (44.0%), followed by health facilities (42.0%). Other sources, including community distributors, health providers and family members were poorly used (data not shown).

According to Fig. 4, several sources of information about FP were used by adolescent girls. However, of all, television was the most used by one in four (26%); followed by radio (20%) and health facilities (16%). The least used source of information was the short messaging (SMS) (1%) Fig. 4.

Teenagers spontaneously mentioned fifteen contraceptive methods they had already heard of. Of these, 13 (86.7%) were modern methods and two (13.3%) were traditional methods. The best-known FP methods were the male condom (86.0%), rhythm methods (65.0%), injectables (60.0%), implants (53.0%), contraceptive pills (50.0%), female condom (50.0%), coitus interruptus (46.0%) and female sterilization (44.0%). The least known FP methods included diaphragm (3.0%), contraceptive jelly (6.0%), male sterilization (9.0%), breastfeeding method (9.0%), emergency pill (14.0%), IUDs (16.0%) and cyclebeads (21.0%). As part of the assessment of adolescents' knowledge of contraceptive methods, we checked how many methods they had heard about. Thus, 79.0% adolescent girls cited at least 3 out of 15 contraceptive methods. A few adolescents (21.0%) cited less than 3 contraceptive methods among those they had heard of Fig. 5.

The use of modern or traditional contraceptive methods was influenced by some characteristics of adolescents. We present the results of the bivariate analysis using the Pearson Chi-square test. According to these results, on one hand, the use of traditional contraceptive methods by sexually active adolescent girls was associated with five variables, including knowledge of contraceptive methods (p = .002), level of education (p = .022), religion (p = .007), number of children (p = .046) and province (p < .001). On the other hand, the use of modern contraceptive methods was associated with two variables, including knowledge of contraceptive methods (p < .001) and household income (p = .002). However, six independent variables were associated with the use of any contraceptive method by sexually active adolescents. These are knowledge of contraceptive methods (p < .001), level of education (p = .002), religion (p = .017), number of children (p = .039), household income (p = .008) and province (p < .001). As shown in Table 3, only knowledge of contraceptive methods was associated with the use of any, modern and traditional FP methods. Table 3

The logistic regression (Tables 4, 5, 6) helped to measure the relationship between the “use of any, modern or traditional contraceptive methods by sexually active adolescent girls” and the independent variables. According to the results in Table 4, before and after adjusting the data, the use of modern contraceptive methods by sexually active teenagers was associated to adolescent’s knowledge of contraceptive methods (p = .002). Teenagers with poor knowledge of FP were significantly more likely not to use modern contraceptive methods compared to the second group (Adjusted OR = 23.100; 95%CI, 3.295–161.942; p = .002). Table 4

As shown in Table 5, before and after adjusting the data, two independent variables were significantly associated with the “use of traditional FP methods by sexually active adolescent girls”. These variables are religion (p < .038) and the province of residence (p < .001). On one hand, Christian teenagers were significantly more likely not to use traditional FP methods than non-Christian adolescents (Adjusted OR = 2.009; 95%CI, 1.039–3.885; p = .038). On the other hand, adolescent women living in Kongo Central were significantly more likely not to use traditional contraceptive methods than those living in Kinshasa (Adjusted OR = 5.372; 95%CI, 2.904–9.637; p < .001). Table 5

Unlike Tables 4 and 5, the results of Table 6 show that 3 independent variables were associated with the use of any contraceptive method by sexually active adolescent girls; these are knowledge of contraceptive methods, household income and province. Thus, characteristics such as low knowledge of contraceptive methods (Adjusted OR = 8.868; 95%CI, 2.997–26.240; p < .001); belonging to low-income households (Adjusted OR = 1.797; 95%CI, 1.099–2.940; p = .020); and living in Kongo Central province (Adjusted OR = 3.170; 95%CI, 1.974–5.091; p < .001) made teenagers more likely not to use any contraceptive methods than those without these factors. Table 6

Discussions

The results of this study confirm the upward trend in contraceptive prevalence provided through the last Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS-RDC 2018) [23]. When compared to the results of the last Demographic and Health Survey (DHS-RDC 2013–14) [33]; and the targets set through the multisector FP strategic plan [34], these findings suggest an improvement in the use of contraceptive methods, particularly among never-married adolescents. In 2014, the DHS-RDC reported a contraceptive prevalence of 11.5, 5 and 6.5% in adolescents; respectively for any, modern and traditional FP methods [33]. These results are consistent with what have been reported in the literature. Never-married women usually have the highest contraceptive prevalence than currently married women [35].

Although clearly increasing, the proportion of adolescent girls using contraception in the DRC remains low compared to the African average. Actually, from 2013 to 2019, the use of modern contraceptive methods improved less among sexually active adolescents (married or living as a couple), from 5.4 to 9.5% than in adult women, among whom it ranked from 7.8 to 17.6% [23, 33]. However, these results contrast with those found by Kennedy et al. [36] and Munakampe et al. [17] who reported more progress in adolescents’ contraceptive use compared to women aged 20–49.

Our results indicated a significant decrease in unmet FP needs among adolescents compared with previous studies, namely DHS-RDC 2013 [33] and MICS-RDC, 2018 [23]. This obsevation can be explained by the fact that the aforementioned studies were organized at the national level; while this study took place only in Kinshasa and Kongo Central. These provinces located near the political decision-makers have benefited significant support from the Ministry of Health (MOH). However, according to the findings of this study, adolescent girls residing in the rural area of Kongo Central have higher unmet needs for contraception than those living in the urban area (Kinshasa). These results suggest a problem of equity in the distribution of FP services between rural and urban areas, already highlighted by Mpunga et al. [20]. Although contraceptive prevalence is high among women in Kongo Central, compared to that of Kinshasa, Kongo Central also registers a significant proportion of unmet need. This paradoxical result can be explained by the results in Table 1 which showed that the proportion of women in union is high in Kongo Central compared to Kinshasa. A previous study has shown that never-married women are significantly more likely to have their demand for contraceptive use satisfied than formerly married women [35]. According to Gilda et al. [37], women with unmet needs for FP cite infrequent sex, unmarried status, and the side effects of contraceptive methods as discouraging the use of modern contraception. These observations are consistent with the results in Fig. 3.

This weak progress nevertheless reflects the considerable efforts made by the government of the DRC with a gradual improvement of the supply of FP methods [25] and the development of innovative approaches [26, 27].

Given to these results, the DRC could not reach the target of the FP strategic plan set at least 19% of modern contraceptive prevalence by 2020 [34]. Barriers to accessing contraceptive services, related to supply and demand; and misconceptions of providers, users and the community about some modern methods could explain this state of affairs [38]. Other barriers are related to the health system, including the low availability of user-friendly services [20, 21] and the issue of equity [39]. Health facilities (HFs) are often inaccessible, unacceptable, inappropriate and ineffective for disadvantaged adolescents [40]. Some HFs not offering traditional methods are likely not to be used by some adolescents [21].

Other barriers are related to the characteristics of adolescent girls. We showed that the practice of the Christian religion could hinder the use of certain contraceptive methods by adolescent girls. However, some adolescent girls are not attached to Christian values that encourage the practice of sexuality only within the framework of marriage. One study showed that unmarried teens who regularly attend religious services are less likely to have ever had sex than others [41]. It is shown that most sexually active women of all beliefs—including Catholic women—whether single or married, use contraception when they do not want to become pregnant [41]. Few studies have assessed the relationship between adolescent religious attendance and contraceptive use, and their results are mixed. Consistent with our findings, some studies have found that adolescents with higher religiosity or more conservative religious affiliations are less likely than others to use birth control methods during sex [42, 43]. Other researchers have found no association between religion and contraceptive uptake [44, 45].

Limited knowledge about contraception has been shown to be a major barrier to accessing and using this service, especially among unmarried adolescents [17, 46,47,48]. Considering the results of this work, we found that the majority of adolescents cited at least three different contraceptive methods. Despite this fact, only one in five teenage girls uses any contraceptive method. Thus, this result suggests organizing a more in-depth analysis of the unfavorable attitudes to contraception which could be linked to negative cultural attitudes, in particular towards premarital sex [49]. According to Sneha et al. [50], adolescent girls' willingness and ability to use contraceptive services are often negatively affected by interpersonal influences (peers, partners, and parents); community influences (social norms) and macro-social influences involving religion in particular. Munakampe et al. [17] and Borraccino et al. [51] suggest the implementation of interventions involving parents and teachers in order to convey healthy messages to adolescents. Parental control discriminates more against the sexual behavior of adolescents [52], open parental communication on sexuality and comprehensive sexual education at school appear to be protective factors against the occurrence of early and unplanned pregnancies. These factors identified by Krugu et al. [53] should be targeted by intervention programs at the individual, interpersonal, school and community levels. Apart from sex education by parents, the attitude of health providers needs to be improved to facilitate the use of contraceptive services [54, 55].

Male condoms are the best known and most widely used contraceptive method among teenage girls, followed by rhythm methods. These results corroborate those found during the 2013 DHS survey [33]. The effectiveness of most natural/traditional methods is high, varying from 90 to 98% if the method is understood and well used by the couple [56, 57]; coitus interruptus being the least effective method. In this study, we have shown that four out of ten adolescent girls use traditional contraceptive methods, mainly in Kinshasa compared to Kongo Central. This observation could be explained by the level of education which is usually high in urban areas unlike in rural areas. However, most traditional FP methods depend on user intervention and then have a greater risk of failure than those that do not depend on the user. The success of natural methods largely depends on the level of education, knowledge and practices of the users [58]. Adolescents must therefore benefit from effective sex education programmes; to achieve this goal, guidelines on sex education can be applied [59].

Strengths and limitations

Limitations of our analysis include the fact that the data on other determinants of contraceptive use, access to health information and services, discussion between couples, women’s autonomy, and cultural barriers were not available. Dichotomizing covariates in this study can lead to residual counfounding. Other weakness lies in the fact that the study took place in two provinces of the DRC, not nationwide representation. Due to the small number of observations concerning certain variables, some confidence intervals are wide. Finally, because the analyses used cross-sectional data, causality could not be determined. However, this study covered a representative sample of adolescent girls aged 15–19 whose selection was made randomly. The data were weighted as part of the analyses.

Conclusions

This study shows an early improvement in the uptake of contraceptive methods among adolescent girls aged 15–19 in the DRC. However, the progress in the use of FP methods is not yet sufficient. A significant proportion of adolescents use traditional contraceptive methods; and others are not yet using any contraceptive method. Unmet FP needs are gradually decreasing, but remain high, especially in rural areas. The use of contraceptive methods by adolescent girls is influenced by some socio-demographic charasteristics. Poor knowledge of contraceptive methods, low household income as well as residence in rural areas prevent adolescents from using any contraceptive methods. In order to improve the use of contraception, in addition to actions on socio-demographic factors, it is necessary to make contraceptive services available and accessible for adolescents. Comprehensive sexuality education programs should be offered by schools, health providers and parents.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used in this study are the data of the PMA 2020 Round 7, 2018. They can be obtained on reasonable request to be sent to the PMA team.

Abbreviations

- FP:

-

Family planning

- DRC:

-

Democratic Republic of the Congo

- SRH:

-

Sexual and reproductive health

- EA:

-

Enumeration areas

- PMA 2020:

-

Performance Monitoring Accountability 2020

- IUDs:

-

Intrauterine devices

- MICS:

-

Multi indicators clusters suvery

- DHS:

-

Demographic and health survey

- MOH:

-

Ministry of Health

- RHS:

-

Reproductive health service

- RIPSEC:

-

Renforcement Institutionnel pour des Politiques de Santé basées sur l’Evidence au Congo

- HFs:

-

Health facilities

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- ESPK:

-

Ecole de Santé Publique de Kinshasa

References

Darroch JE, Woog V, Bankole A, Ashford LS. Adding It Up: costs and benefits of meeting contraceptive needs of adolescents. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2016.

Frappier J-Y, Kaufman M, Baltzer F, et al. Sex and sexual health: a survey of Canadian youth and mothers. Paediatr Child Health. 2008;13(1):25–30.

UNFPA. Facing the facts: adolescent girls and contraception. Brochure 2015.

Hoffman SD, Maynard RA, Kids having Kids: economic costs and social consequences of teen pregnancy. Urban Institute Press 2008. Washington, D.C.

Undie C, Birungi H, Odwe G, Obare F. Expanding access to secondary school education for teenage mothers in Kenya: a baseline study report. STEP UP research report 2015. Strengthening Evidence for Programming on Unintended Pregnancy (STEP UP). Nairobi: Population Council.

Gottschalk LB, Ortayli N. Interventions to improve adolescents’ contraceptive behaviors in low- and middle-income countries: a review of the evidence base. Contraception. 2014;90(3):211–25.

Birungi H, Undie C, Mackenzie I, Katahoire A, Obare F, Machawira P. Education sector response to early and unintended pregnancy: a review of country experiences in sub-Saharan Africa. STEP UP and UNESCO research report 2015. Strengthening Evidence for Programming on Unintended Pregnancy (STEP UP). Nairobi: Population Council and UNESCO.

Panova OV, Kulikov AM, Berchtold A, Suris JC. Factors associated with unwanted pregnancy among adolescents in Russia. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29(5):501–5.

Human Reproduction Programme (HRP), WHO, STEP UP, Population Council, UKaid. Family Planning Evidence brief _ Reducing early and unintended pregnancies among adolescents. WHO/RHR/17.10 Rev.1, 2018.

Blanc KA, Tsui OA, Croft NT, Trevitt LJ. Patterns and trends in adolescents’ contraceptive use and discontinuation in developing countries and comparisons with adult women. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;35(2):63–71.

Dennis LM, Radovich E, Wong MLK, Owolabi O, Cavallaro LF, Mbizvo TM, et al. Pathways to increased coverage: an analysis of time trends in contraceptive need and use among adolescents and young women in Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda. Reprod Health. 2017;14:130.

Kantorova’ V, Wheldon MC, Dasgupta ANZ, Ueffing P, Castanheira HC. Contraceptive use and needs among adolescent women aged 15–19: regional and global estimates and projections from 1990 to 2030 from a Bayesian hierarchical modelling study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(3):e0247479.

Li Z, Patton G, Sabet F, Zhou Z, Subramanian SV, Lu C. Contraceptive use in adolescent girls and adult women in low- and middle-income countries. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2): e1921437.

Carolina de Vargas N, Ewerling F, Hellwig F, Dornellas de Barros JA. Contraception in adolescence: the influence of parity and marital status on contraceptive use in 73 low-and middle-income countries. Reprod Health. 2019;16:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0686-9.

Tsui OA, Brown W, Li Q. Contraceptive practice in Sub-Saharan Africa. Popul Dev Rev. 2017;43(1):166–91.

Taghizadeh MH, Bahreini A, Ajilian AM, Fazli F, Saeidi M. Adolescence health: the needs, problems and attention. Int J Pediatr. 2016;4(2):1423–38.

Munakampe NM, Zulu MJ, Michelo C. Contraception and abortion knowledge, attitudes and practices among adolescents from low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:909. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3722-5.

Hindin MJ, Kalamar AM, Thompson TA, Upadhyay UD. Interventions to prevent unintended and repeat pregnancy among young people in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review of the published and gray literature. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(3):S8-15.

UNFPA. Review of adolescent and youth policies, strategies and laws in selected Countries in West Africa. UNFPA 2017. P. 1–46.

Mpunga MD, Lumbayi J-P, Dikamba MN, Mwembo TA, Mapatano MA, Wembodinga UG. Availability and quality of family planning service in DR Congo: high potential Improvement. Glob Health: Sci Pract. 2017;5(2):274–85.

Mpunga MD, Chenge MF, Mapatano MA, Wembodinga UG. Exploring the adequacy of family planning services to adolescents needs: results of a cross-sectional study from two settings in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Health Educ Pub Health. 2018;2(1):131–41.

Journal officiel de la RDC. Loi N° 16/008 du 15 juillet 2016 modifiant et complétant la loi N°87–010 du 1er Aout 1987 portant Code de la famille.

Institut National de la Statistique. Enquête par grappes à indicateurs multiples, 2017–2018, rapport de résultats de l’enquête. Kinshasa: République Démocratique du Congo; 2019. p. 1–400.

Chae S, Kayembe KP, Philbin J, Mabika C, Bankole A. The incidence of induced abortion in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. PLoS ONE. 2016;12(10): e0184389. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184389.

Kwete D, Binanga A, Mukaba T, Nemuandjare T, Mbadu MF, Kyungu M-T, et al. Family planning in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: encouraging momentum, formidable challenges. Family planning in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: encouraging momentum, formidable challenges. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2018;6(1):40–54. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00346.

Mwembo A, Emel R, Koba T, Bapura SJ, Ngay A, Gay R, et al. Acceptability of the distribution of DMPA-SC by community health workers among acceptors in the rural province of Lualaba in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: a pilot study. Contraception. 2018;98:454–9.

Hernandez HJ, Akilimali ZP, Mbadu MF, Glover LA, Bertrand TJ. Evolution of a large-scale community-based contraceptive distribution program in Kinshasa, DRC based on process evaluation. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2018;6(4):657–67. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-18-00205.

Tulane University School of Public Health, University of Kinshasa School of Public Health and The Bill & Melinda Gates Institute for Population and Reproductive Health at The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Performance Monitoring and Accountability 2020 (PMA2020) Survey Round 7, PMA2018/DRC-R7 (Kinshasa & Kongo Central), 2018. Kinshasa, DRC and Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Festin MPR, Kiarie J, Solo J, Spieler J, Malarcher S, van Look PFA, Temmerman M. Moving towards the goals of FP2020–classifying contraceptives. Contraception. 2016;94:289–94.

République Démocratique du Congo. Loi N°18/035 du 13 décembre 2018 fixant les principes fondamentaux relatifs à l’organisation de la santé publique. Journal officiel de la République Démocratique du Congo 2018. https://www.leganet.cd /Legislation/Droit Public/SANTE/Loi.18.035.13.12.2018.html#TitreII.

Akilimali PZ, Nzuka HE, LaNasa KH, Wumba AM, Kayembe P, Wisniewski J, et al. The gap in contraceptive knowledge and use between the military and non-military populations of Kinshasa, DRC, 2016–2019. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(7): e0254915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254915.

Rosenberg RE, Akilimali PZ, Hernandez JH, Bertrand JT. Factors influencing client recall of contraceptive counseling at community-based distribution events in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:784. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06796-4.

Ministère du Plan et Suivi de la Mise en œuvre de la Révolution de la Modernité (MPSMRM) ; Ministère de la Santé Publique (MSP); ICF International. Enquête démographique et de santé en République Démocratique du Congo 2013–2014. Rockville, Maryland: MPSMRM, MSP, and ICF International; 2014.

République Démocratique du Congo (RDC). Planification familiale: plan stratégique national à vision multisectorielle 2014–2020. Kinshasa: RDC 2014. p. 1–50.

Wenjuan W, Staveteig S, Winter R and Allen C. Women’s marital status, contraceptive use, and unmet need in Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. DHS Comparative Reports No. 44. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF, 2017.

Kennedy E, Gray N, Azzopardi P, Creati M. Adolescent fertility and family planning in East Asia and the Pacific: a review of DHS reports. Reprod Health. 2011;8:11.

Sedgh G, Hussain R. Reasons for contraceptive nonuse among women having unmet need for contraception in developing countries. Stud Fam Plan J. 2014;45(2):151–69.

Ho LS, Wheeler E. Using program data to improve access to family planning and enhance the method mix in conflict-affected areas of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2018;6(1):161–77. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00365.

Ortayli N, Malarcher S. Equity analysis: identifying who benefits from family planning programs. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41(2):101–8.

Ministère de la santé publique. Normes de la zone de santé relatives aux interventions intégrées de santé de la mère, du nouveau-né et de l’enfant en République Démocratique du Congo: interventions de santé adaptées aux adolescents et jeunes. Version. 2012;5:1–20.

Mpunga MD, Chenge MF, Mapatano MA, Mambu TNM, Wembodinga GU. Assessing comprehensive sexuality education programs in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: adolescents’ and teachers’ knowledge. Attitudes Pract Towards Contracept Health. 2020;12:1428–44.

Thongmixay S, Essink DR, Greeuw T, Vongxay V, Sychareun V, Broerse JEW. Perceived barriers in accessing sexual and reproductive health services for youth in Lao People’s Democratic Republic. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(10): e0218296.

Nmadu AG, Mohammed S, Usman NO. Barriers to adolescents’ access and utilisation of reproductive health services in a community in north-western Nigeria: a qualitative exploratory study in primary care. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2020;12(1):e1-5.

Jones RK, Dreweke J. Countering conventional wisdom: new evidence on religion and contraceptive use. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2011. p. 1–8.

Nonnemaker JM, McNeely C, Blum R. Public and private domains of religiosity and adolescent health risk behaviors: evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:2049–54.

Brewster KL, Cooksey EC, Guilkey DK, et al. The changing impact of religion on the sexual and contraceptive behavior of adolescent women in the United States. J Marriage Fam. 1998;60:493–504.

Sedgh G, Ashford LS, Hussain R. Unmet need for contraception in developing countries: examining women’s reasons for not using a method, New York: Guttmacher Institute. Report 2016. p. 1–93.

Parks C, Peipert FJ. Eliminating health disparities in unintended pregnancy with long-acting reversible contraception (LARC). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(6):681–8.

Jones R, Darroch J, Singh S. Religious differentials in the sexual and reproductive behaviors of young women in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36:279–88.

Challa S, Manu A, Morhe E, Dalton KV, Loll D, Dozier J, et al. Multiple levels of social influence on adolescent sexual and reproductive health decision-making and behaviors in Ghana. Women Health. 2018;58(4):434–50.

Borraccino A, Lo Moro G, Dalmasso P, Nardone P, Donati S, Berchialla P, Charrier L, Lenzi M, Spinelli A, Lemma P; 2018 HBSC-Italia Group; the 2018 HBSC-Italia Group. Sexual behaviour in 15-year-old adolescents: insights into the role of family, peer, teacher, and classmate support. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2020;56(4):522–30.

Yode M, LeGrand T. Association between family environment and sexual behaviour of adolescents in Burkina Faso. Adv Reprod Sci. 2014;2:33–45.

Krugu KJ, Mevissen FEF, Prinsen A, Ruiter RAC, et al. Who’s that girl? A qualitative analysis of adolescent girls’ views on factors associated with teenage pregnancies in Bolgatanga, Ghana. Reprod Health. 2016;13:39.

Onokerhoraye AG, Dudu JE. Perception of adolescents on the attitudes of providers on their access and use of reproductive health services in Delta State. Niger Health. 2017;9:88–105.

Chilinda I, Hourahane G, Pindani M, Chitsulo C, Maluwa A. Attitude of health care providers towards adolescent sexual and reproductive health services in developing countries: a systematic review. Health. 2014;6:1706–13.

Frank-Herrmann P, Heil J, Gnoth C, Toledo E, Baur S, Pyper C, Jenetzky E, Strowitzki T, Freundl G. The effectiveness of a fertility awareness-based method to avoid pregnancy in relation to a couple’s sexual behaviour during the fertile time: a prospective longitudinal study. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(5):1310–9.

Gray RH, Kambic TR, Lanctot AC, Martin CM, Wesley R, Cremins R. Evaluation of natural family planning programmes in Liberia and Zambia. J Biosoc Sci. 1993;25(2):249–58.

OMS. Département de santé et recherche en matière de reproduction, Johns Hopkins Ecole de santé publique Bloomberg. Centre pour les programmes de communication Projet INFO. & Agence des Etats-Unis pour le développement international. Bureau de santé globale. Office de la Population et de la Santé Reproductive. Planification familiale : un manuel à l'intention des prestataires de services du monde entier : mise à jour 2011: directives factuelles mises au point dans le cadre d'une collaboration mondiale. Organisation mondiale de la Santé 2011.

UNESCO, UNICEF, UNFPA, UN Women, WHO and UNAIDS. International technical guidance on sexuality education - An evidence-informed approach. 2018.

Acknowledgements

We thank the managers of the Performance, Monitoring and Accountability (PMA2020) project for agreeing to make available the data of Round 7 from the DRC. We also thank the managers of the project, ‘Renforcement Institutionnel pour des Politiques de Santé basées sur l’Evidence au Congo (RIPSEC)’, who gave us support to finalize this manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DMM and GUW designed the project. DMM requested data from the PMA 2020 team; performed the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. PZA, FMC, MAM, TNMM and GUW contributed to the interpretation of the data and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) from the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Tulane University and the Kinshasa School of Public Health (KSPH). The PMA2020 data were publicly available from the PMA website, having undergone IRB review at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (#14702). All participating women aged 15–19 provided a written and informed consent to participate to the study. The ethics committee of the KSPH granted waiver of parental or legal guardian consent for emancipated women aged 15 to 17, under approval number ESP/CE/73B/2018. The study did not represent a major risk for their participation. The authors confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mpunga, D.M., Chenge, F.M., Mambu, T.N. et al. Determinants of the use of contraceptive methods by adolescents in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: results of a cross-sectional survey. BMC Women's Health 22, 478 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-02084-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-02084-3