Abstract

Background

There is limited national representative evidence on determinants of women’s acceptance of wife-beating especially; community level factors are not investigated in Ethiopia. Thus, this study aimed to assess individual and community-level factors associated with acceptance of wife beating among reproductive age women in Ethiopia.

Methods

Secondary data analysis was done on 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey data. A total of 15,683 weighted reproductive age group women were included in the analysis. Multi-level mixed-effect logistic regression analysis was done by Stata version 14.0 to identify individual and community-level factors. An adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval was used to show the strength and direction of the association. Statistical significance was declared at p value less than 0.05 at the final model.

Result

Individual-level factors significantly associated with acceptance of wife-beating among women were; being Muslim follower [AOR = 1.3, 95% CI = (1.1, 1.5)], Being married [AOR = 1.3, 95% CI = (1.1, 1.6)], attending primary, secondary and higher education [AOR = 0.8, 95% CI = (0.7, 0.9)], [AOR = 0.4, 95% CI = (0.3, 0.5)], [AOR = 0.3, 95% CI (0.2, 0.4)] respectively. From community level factors, living in Somali [AOR = 0.2 95% CI = (0.1, 0.3)], Addis Ababa [AOR = 0.3, 95%CI = (0.2, 0.5)] and Dire Dawa [AOR = 0.5, 95% CI = (0.3, 0.7)] were 80%, 70% and 50% less likely accept wife-beating when compare to women who live in Tigray region, respectively. Live in high proportion of poor community [AOR = 1.2, 95% CI = (1.1, 1.3)], live in low proportion of television exposure communities [AOR = 1.4, 95% CI = (1.2, 2.2)] were significantly associated with acceptance of wife-beating among women in Ethiopia.

Conclusion

Educational status, religion, marital status, region, community-level wealth, and community level of television exposure had a statistical association with women’s acceptance of wife-beating. Improving educational coverage, community-level of media exposure, community-level wealth status and providing community-friendly interventions are important to reduce the acceptance of wife-beating among women in Ethiopia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gender-based violence (GBV) is any harm or suffering that is perpetrated against a woman or girl, man or boy and that harms the physical, sexual or psychological health, development, or identity of the person [1,2,3,4]. GBV is a widespread human rights issue, which is critical in gender inequality and disproportionately affected women and girls globally [5,6,7,8,9]. Violence restricts the ability of women and girls to fully participate in and contribute to communities politically, economically, and socially. Women and young girls are disproportionally affected by physical and sexual violence [10,11,12]. Wife beating is common throughout the world [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The burden ranges from 15 to 79% [22]. Partner violence occurs in all countries and transcends social, economic, religious, and cultural groups. Worldwide, one of the most common forms of violence against women is abuse by their husbands or other intimate male partners [23].

Intimate partner violence is high when society accepts it [24,25,26]. Beliefs and norms seem to grant men control over female behavior, making violence acceptable for resolving conflicts [27]. Other studies have suggested that, in societies with a high prevalence of interpersonal violence, attitudes that encourage or tolerate violence against women is viewed as normative behavior [28].

Studies in Ethiopia have also shown that about one-half to two-third of women experience one or other forms of spousal abuse at least once in their lifetime [29,30,31,32,33]. Intimate partner violence affects the utilization of different reproductive health services in different countries [18,19,20,21, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] including Ethiopia [31,32,33, 42,43,44,45,46,47].

In Ethiopia, different researches have been done on the prevalence and/or factors associated with women's attitude towards wife-beating. Age, residence, educational status, and religion are determinant factors identified by scholars [29,30,31,32,33, 42,43,44,45,46]. But, all the studies were done at a local level, use a small sample size, do not consider the effect of community-level factors on women's attitude towards wife-beating. Besides, the association at the individual-level may not work at the community level and vice versa. Even the studies were fitted with standard logistic regression which may lead to loss of power. “National representative evidence is important to achieve the national, international goals towards gender equity, equality, women empowerment and to ensure health for all”. Therefore, this study aimed to assess individual and community-level factors associated with acceptance of wife-beating among—women in Ethiopia by using EDHS 2016 will be important to develop community-level behavioral change communication to reduce the prevalence and impact of intimate partner violence in the country.

Methods

Study setting and period

The study was conducted in Ethiopia, which is located in the North-eastern (horn of) Africa, lies between 30 and 150 North latitude and 330 480 and East longitudes. This study used 2016 EDHS data set which was collected by the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [48]. Data were accessed from their URL: www.dhsprogram.com by contacting them through personal accounts after justifying the reason for requesting the data.

A total of 15,683 weighted reproductive age women were included in the analysis. EDHS 2016 sample was stratified and selected in two stages. In the first stage, stratification was conducted by region, and then each region stratified as urban and rural, yielding 21 sampling strata. A total of 645 (202 urban and 443 rural) enumeration areas [49] were selected with probability proportional to EA size in each sampling stratum. In the second stage affixed number of 28 households per cluster were selected with equal probability systematic selection from the newly created household listing.

Variable measurement and definition

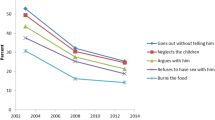

In this study the outcome variable (acceptance of women towards wife-beating) was dichotomized as (Yes/No). Reproductive age women acceptance towards wife-beating was measured by computing the following variables (burning food, arguing with husband, going out without telling husband, neglecting the children, and refusing to have sexual intercourse with her husband). If a women say “yes” at least one from the above five variables, she was considered as accepting wife-beating [48]. The independent variables were individual-level factors including (age, religion, wealth index, educational status, media exposure) and community-level factors were created by aggregating individual-level factors in each cluster (region, residence, community-level of education, community-level wealth index, community-level television exposure, and community-level radio exposure). The community-level of wealth index was generated by using the proportion of the two (poorest and poorer) lowest level of wealth index to the total wealth index of the same cluster. Similarly community-level of education is generated by using the proportion of the two (secondary and higher education) high level of educational attainment to the total the educational level of the same cluster. Community-level of television exposure is also computed by dividing exposed to television for the total respondents, Community-level radio exposure is computed by dividing exposed to radio to the total respondents. Since all the above four variables are not normally distributed, we were using the median as cutoff point (above median: women who live in a cluster with a high proportion of poor community, low community educational status, low community media exposure) to dichotomize the variables.

Data processing and analysis

Data cleaning was conducted to check for consistency with the EDHS-2016 descriptive reports. Recoding, variable generation, labeling, and analysis were done by using Stata version 14.0. Descriptive statistics were done to describe the study participants in relation to socio-demographic characteristics which were presented in tables and text. Sample weight was used to compensate for the unequal probability of selection between the strata that were geographically defined and for non-responses. Multilevel analysis was conducted after checking the eligibility of the data to multilevel analysis by using the intra-cluster correction coefficient (ICC). When the ICC is greater than 10% (ICC = 23%), the community-level factors affect the dependent variable. Therefore it is better to identify community-level factors to develop and take different interventions. Since EDHS data are hierarchical (individual “level 1” were nested within a community “level 2”), a two-level mixed-effects logistic regression model was fitted to estimate both independent (fixed) effects of the explanatory variables and community–level random effects on acceptance of wife-beating among reproductive age women. The log of the probability of accepting wife-beating was modeled using a two-level multilevel model as follows: Log \(\left[\frac{{\Pi_{ij} }}{{1 - \Pi_{ij} }}\right]\) = β0 + β1Xij + B2 Zij + µj + eij, Where i and j are individual level and community level [2] unites respectively; X and Z refers to individual and community level variables respectively; πij is the probability of accepting wife-beating for the ith women in the jth community; β’s indicates the fixed coefficients. (Β0) is the intercept, the effect on the probability of accepting wife-beating in the absence of influencing factors; and µj showed the random effect (the effect of the community on the acceptance of wife-beating of the jth community) and eij showed random errors at individual level. By assuming each community had a different intercept (Β0) and fixed coefficient (β), the clustered data nature and intra and inter-community variations were taken into account.

During analysis first, bi-variable multilevel logistic regression was fitted and variables with p value less than 0.2 at model I and model II were selected to develop the 3rd model (the final model). The analysis was done in four models. The first model was, model-0 (empty model or null model/ without explanatory variable; to secure the need to multilevel analysis). The second model was, model-I (analyzing only individual-level variable), the 3rd model was, model-II (analyzing only community-level variable), the last model, model-III (analyzing both community level and individual level variables based on the cutoff point).

The measure of association (fixed effects) estimate the association between the likelihood of acceptance of wife-beating among reproductive age group women and different explanatory factors were expressed by Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with respective 95% confidence level. Variables with p value less than 0.05 at model-III were significantly associated with acceptance of wife-beating. The random-effects (variations) were measured by using ICC (model-0), Median Odds Ratio (MOR) in (model-I and II), and Proportional Change in Variance (PCV) was measured to show variation between clusters.

ICC shows the variation in acceptance of wife-beating among women due to community characteristics. The higher the ICC, the community characteristics are more relevant to understand individual variation for acceptance of wife-beating. It is calculated as \({\text{ICC}} = \left( {\frac{{\delta^{2} }}{{\delta^{2} + \frac{{\pi^{2} }}{3}}}} \right)\), where δ2 indicates estimated variance of clusters. MOR is the median value of the odds ratio between the area at highest risk and the area the lowest risk when randomly picking out two areas and it was calculated as MOR = exp. (\(\sqrt {2 \times \delta^{2} + .6745}\)) ≈ exp(0.95δ). In this study, MOR shows the extent to which the individual probability of accepting wife-beating for women determined by place of residence. PCV measures the total variation attributed by individual-level variables and area-level variables in the final model (model-III). It is calculated as PCV = [δ2 of null model − δ2 of each model)/δ2 of null model]. δ2 of the null model is used as a reference.

Multicollinearity was checked among explanatory variables by using standard error at a cutoff point ± 2. No Multicollinearity is the standard errors were between ± 2. The log-likelihood test was used to estimate the goodness of fit of the adjusted final model (model-III) in comparison to the preceding models (model-I and model-II) individual and community model adjustments respectively. The analysis was done by using the SVY Stata commands to control the clustering effect of complex sampling (stratification and multistage sampling procedures).

Results

Characteristics of the respondents

A total of 15,683 reproductive age [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49] women were included in the analysis. Among this, 3380.9 (21.6%) were found in the age group of 15–19 years, 7497.9 (47.8%) study participants have not attended school. About 12,207 (77.8%) of women residing in rural areas. 11,359.5 (72.4%) of women live in areas of the low proportion educated community (Table 1).

Individual and community level factors associated with women acceptance of wife beating

In the final model (model-III) educational status, religion, marital status, region, community-level wealth, and community-level of television exposure had a statistical association with women acceptance of wife beating.

The odds of women acceptance on wife beating was 1.3 times more among participants who are Muslim religion followers as compared to Orthodox religion followers [AOR = 1.3, 95% CI = (1.1, 1.5)]. Women who were attending primary education, secondary education and higher education were 20%, 60% and 70% less likely accept wife beating when compared with not attend school [AOR = 0.8, 95% CI = (0.7, 0.9)], [AOR = 0.4, 95% CI = (0.3, 0.5)], [AOR = 0.3, 95% CI (0.2, 0.4)] respectively.

The odds of women acceptance on wife beating was 1.3 times more among married women when compared with never married women [AOR = 1.3, 95% CI = (1.1, 1.6)]. Women who were living in Somali, Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa were 80%, 70% and 50% less likely accept wife beating when compare to women who live in Tigray region [AOR = 0.2 95% CI = (0.1, 0.3)], [AOR = 0.3, 95%CI = (0.2, 0.5)] and [AOR = 0.5, 95% CI = (0.3, 0.7)] respectively.

Women who live in a high proportion of poor communities were 1.2 times more likely accepted wife-beating than women who live in a low proportion of poor communities [AOR = 1.2, 95% CI = (1.1, 1.3)]. Women who live in a low proportion of television exposure communities were 1.4 times more accept wife-beating than women who live in a high proportion of television exposure community [AOR = 1.4, 95% CI = (1.2, 2.2)] (Table 2).

Random effects (measures of variation)

Women's acceptance towards wife-beating varies significantly across each cluster. ICC indicated, 23.3% of the variation in acceptance of wife-beating among women was attributed to community-level factors. PCV in the final model shows 60% of the variation in acceptance towards wife-beating across communities was explained. Likewise, MOR for acceptance towards wife-beating among women, in the null model was 8.1 which shows the presence of variation across each cluster (Table 3).

Discussion

The result of the final model showed that individual-level factors:( educational status, religion, marital status) and community-level factors:( region, community-level of wealth, and community-level of television exposure) were determinant factors of wife-beating acceptance among reproductive age women in Ethiopia.

As educational attainment increases the acceptance of wife-beating is reduced. The finding is consistent with previous researches. In Ethiopia, refusing wife-beating was differed by educational attainment [32]. A study conducted in seven Asian countries also revealed that better-educated women were more likely to disapprove of wife-beating than less educated ones [50]. Moreover, researches conducted in Israel [51], Korea [52], India [53], Palestine [13], and seventeen sub-Saharan African countries (including Ethiopia) [54] had also come up with consistent findings. According to WHO, education is the strongest demographic predictor explaining wife-beating attitudes [55]. This might be due to Education, being a mechanism of acquiring knowledge, developing common understanding, and enhancing decision-making autonomy, it appeared to have a direct relationship with resistances against wife-beating [32]. Research findings reveal that better-educated women have not accepted the socio-cultural settings of the society rather guided by logic and common understanding based on modern and rational thinking [13, 32, 56, 57]. The inverse relationship between educational attainment and dependency syndrome of wives on their husbands to earn their living has also accelerated a better-educated women’s resistance to wife-beating [56, 58, 59]. It is clearly identified that education is not only one of the best indicators of women’s status in society, but also the other effective and powerful means of ending violence against women [60]. The direct relationship between education and resistance against wife-beating is also a reflection of education’s power to diminish socio-cultural factors [61] that perpetuate males in traditional societies like Ethiopia. Moreover, Educated women are likely to be in a more modern and egalitarian relationship than uneducated women with their husbands [62]. Currently, girls’ education is on the government priority agenda in Ethiopia. Therefore, the proportion of educated young women is expected to rise and to continue having an impact on the reduction of acceptance of wife-beating in the future.

Muslim religion follower women were more accepting wife-beating than Orthodox religion follower women. Similarly, in previous research conducted in Ethiopia, Muslims are accepting wife-beating than Orthodox [32]. In research among seven sub-Saharan African countries, attitude towards wife-beating and religion, Muslims in Mali and Benin were more likely to justify wife-beating [54]. A study in Ghana also revealed that compared to Christian women, Muslims were more likely to approve physical violence against wives [63]. This might be, religion tends to clutch abundant moral values affecting the power relation between husband and wife [14, 64,65,66]. More religious women are believed to hold the conservative and traditional belief that stimulates husbands’ to abuse their wives [67]. Potential explanations include the influence of religious traditions, teachings, doctrines, religious communities, and institutions that convey values and belief systems to their members.

Currently married women tend to accept wife-beating than never-married women. The finding is supported by research in Ethiopia [32]. This is believed to be the effect of the socio-cultural influences which have been supported by traditional norms and values that have allowed Ethiopian males to ‘discipline’ their wives and correct them to their wants. It may be that ever-married women, having experienced domestic violence firsthand, might respond to the EDHS that fits in with community attitudes. By contrast, never-married women may have better knowledge about rights, gender equality, and female empowerment, which could encourage this group of women to challenge traditional norms that require women to be submissive to their husbands. Never-married women are more likely to be educated than their never-married counterparts. This suggests that these attitudes are modifiable and that community norms and public discourse are powerful determinants of individual attitudes and values about gender-based norms [38, 68].

There is a regional variation in acceptance of wife-beating among women. Women who live in Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa, Harari, and Somali region are less likely to accept wife-beating when compared with women who live in Tigray region. Cultural, religious values, and norms may be different across the regions [69]. Cultural norms, social changes, family dynamics, and government policies influence attitude [13, 32, 38, 57, 70]. Living in urban areas facilitates exposure to people from diverse backgrounds, living arrangements, and lifestyles which, in turn, can promote gender-egalitarian views [49, 71].

When a high proportion of poor people lived in the cluster, the acceptance of wife-beating increased. This is also supported by a study conducted in sub-Saharan African countries [62, 72]. This might be due to rich communities can offer greater opportunities for higher education and employment [73,74,75,76]. This, in turn, can positively impact women’s attitudes [70]. Research documents, lower levels of wife-beating acceptance among those living in advantaged communities [38, 57, 68]. Moreover, women in the poor community might face economic, social, and educational constricts to challenge the norms which force them to accept existing social views [49, 77,78,79,80].

When a low proportion of people espoused to television in the cluster, the acceptance of wife-beating increased. The finding is consistent with a search conducted in Ethiopia [42] and seventeen countries of sub Saharan Africa [54]. That revealed that women who live in a cluster of low access to media information were more supportive of wife-beating than their counterparts. This might be, Media exposure creates awareness about the existing law against women discrimination in the country which is a key factor influencing the tendency of women to believe wife-beating is justified [17, 81, 82]. More specifically, the study confirms that women who lack awareness of the existing law that prohibits wife-beating in Ethiopia are most likely to support wife-beating than women who are aware of the existing law [42]. Media espouse might change the community and women's believes that women benefit and gain from violence [83].

The result of this study was more representative than other studies and the model considered different levels of analysis as the outcome was affected by community-level variables. Despite this strength, the result may be prone to recall bias because the data were collected from history of event.

Conclusion

After computing multi-level analysis, low educational status, being married, Muslim religion followers, region, live in high a proportion of poor community, live in a high proportion of non-television exposed community had a statistical association with acceptance of wife-beating among reproductive age group women in Ethiopia. Improving universal access to education is important to reduce the prevalence as well as health and health-related complications of the acceptance of wife-beating. Advocacy and behavioral change communication should be area of concern for different organizations who are working on women reproductive health to tackle the acceptance as well as the consequences of gender-based violence. Since the acceptance of wife-beating is different across community, better to develop community sensitive approaches for different communities.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CSA:

-

Central statistics agency

- EA:

-

Enumeration area

- ICC:

-

Inter cluster coefficient

- MOR:

-

Median odds ratio

- PCV:

-

Proportional change variance

References

Parkes J. Gender-based violence in education: UNESCO; 2015.

Kakujaha-Matundua O. Towards Identifying and estimating public expenditure on gender-based violence in Namibia. SOCIAL SCIENCES DIVISION (SSD). 2015:110.

Mukungu K, Kamwanyah NJ. Gender-based violence: victims, activism and Namibia’s dual justice systems. In: Doerner WG, editor. Victimology. Berlin: Springer; 2020. p. 81–114.

Machisa M, van Dorp R. The gender based violence indicators study: botswana. Dakar: African Books Collective; 2012.

Plan O II. Ministry of health and social welfare. Health. 2015;2:1.

BRIEF PBP. Dramatically reduce gender-based violence and harmful practices.

Nestorovska G, Kadriu B, Piperevski G. Assesment of the legislation regarding gender–based violence and human trafficking and smuggling in Macedonia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania and Kosovo. 2016.

Dominey-Howes DAG-M, McKinnon S, Bouma M. Gender and Emergency Management (GEM) guidelines A literature review.

Jones J. The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the Council of Europe Convention on Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence (Istanbul Convention). In: Manjoo R, Jones J, editors. The Legal Protection of Women From Violence. Cambridge: Routledge; 2018. p. 147–73.

Montoya C. From global to grassroots: The European Union, transnational advocacy, and combating violence against women. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013.

Lamont R. Beating domestic violence-assessing the EU’s contribution to tackling violence against women. Common Market L Rev. 2013;50:1787.

Weldon SL, Htun M. Feminist mobilisation and progressive policy change: why governments take action to combat violence against women. Gender Dev. 2013;21(2):231–47.

Dhaher EA, Mikolajczyk RT, Maxwell AE, Krämer A. Attitudes toward wife beating among Palestinian women of reproductive age from three cities in West Bank. J Interpers Viol. 2010;25(3):518–37.

Eidhamar LG. My husband is my key to paradise Attitudes of Muslims in Indonesia and Norway to spousal roles and wife-beating. Islam Christ-Muslim Relat. 2018;29(2):241–64.

Haj-Yahia MM, Shen AC-T. Beliefs about wife beating among social work students in Taiwan. Int J Off Therapy Compar Criminol. 2017;61(9):1038–62.

Krause KH, Gordon-Roberts R, VanderEnde K, Schuler SR, Yount KM. Why do women justify violence against wives more often than do men in Vietnam? J Interpers Viol. 2016;31(19):3150–73.

Krause KH, Haardörfer R, Yount KM. Individual schooling and women’s community-level media exposure: a multilevel analysis of normative influences associated with women’s justification of wife beating in Bangladesh. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(2):122–8.

McGee RW. Has wife beating become more acceptable over time? An empirical study of 33 Countries. An Empirical Study of. 2017;33.

Osei-Tutu EM, Ampadu E. Domestic violence against women in Ghana: the attitudes of men toward wife-beating. J Int Women’s Stud. 2017;18(4):106–16.

Oyediran KA. Explaining trends and patterns in attitudes towards wife-beating among women in Nigeria: analysis of 2003, 2008, and 2013 Demographic and Health Survey data. Genus. 2016;72(1):11.

Rajan H. When wife-beating is not necessarily abuse: a feminist and cross-cultural analysis of the concept of abuse as expressed by Tibetan survivors of domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2018;24(1):3–27.

Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. The Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1260–9.

Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottemoeller M. Ending violence against women. Population Rep. 1999;27(4):1.

Eye AV, Bogat GA, Leahy K, Maxwell C, Levendosky AA, Davidson WS. The Influence of Community Violence on the Functioning of Women Experiencing Domestic Violence. 2005.

Jewkes R. Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention. The Lancet. 2002;359(9315):1423–9.

Bogat GA, Leahy K, Von Eye A, Maxwell C, Levendosky AA, Davidson WS. The influence of community violence on the functioning of women experiencing domestic violence. Am J Community Psychol. 2005;36(1–2):123–32.

Ellsberg M, Peña R, Herrera A, Liljestrand J, Winkvist A. Candies in hell: women’s experiences of violence in Nicaragua. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(11):1595–610.

Guerra NG, Rowell Huesmann L, Spindler A. Community violence exposure, social cognition, and aggression among urban elementary school children. Child Dev. 2003;74(5):1561–76.

Abeya SG, Afework MF, Yalew AW. Intimate partner violence against women in west Ethiopia: a qualitative study on attitudes, woman’s response, and suggested measures as perceived by community members. Reprod Health. 2012;9(1):14.

Deyessa N, Berhane Y, Ellsberg M, Emmelin M, Kullgren G, Högberg U. Violence against women in relation to literacy and area of residence in Ethiopia. Glob Health Action. 2010;3(1):2070.

Ebrahim NB, Atteraya MS. Women’s decision-making autonomy and their attitude towards wife-beating: Findings from the 2011 Ethiopia’s demographic and health survey. J Immigr Minor Health. 2018;20(3):603–11.

Gurmu E, Endale S. Wife beating refusal among women of reproductive age in urban and rural Ethiopia. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2017;17(1):1–12.

Hailemariam A, Tilahun T. Correlates of Domestic Violence against women in Bahr Dar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2008;28(2):31–62.

McGee RW. Are Women More Opposed to Wife Beating than Men? An Empirical Study of 60 Countries. An Empirical Study of. 2017;60.

Schuler SR, Yount KM, Lenzi R. Justification of wife beating in rural Bangladesh: a qualitative analysis of gender differences in responses to survey questions. Violence Against Women. 2012;18(10):1177–91.

Speizer IS. Intimate partner violence attitudes and experience among women and men in Uganda. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25(7):1224–41.

Takyi BK, Mann J. Intimate partner violence in Ghana, Africa: The perspectives of men regarding wife beating. Int J Sociol Family. 2006;32:61–78.

Tran TD, Nguyen H, Fisher J. Attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women among women and men in 39 low-and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(11):e0167438.

Upadhyay UD, Karasek D. Women’s empowerment and ideal family size: an examination of DHS empowerment measures in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;38:78–89.

Uthman OA, Lawoko S, Moradi T. Sex disparities in attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women in sub-Saharan Africa: a socio-ecological analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):223.

Zaatut A, Haj-Yahia MM. Beliefs about wife beating among Palestinian women from Israel: the effect of their endorsement of patriarchal ideology. Fem Psychol. 2016;26(4):405–25.

Mengistu AA. Socioeconomic and demographic factors influencing women’s attitude toward wife beating in Ethiopia. J Interpers Violence. 2019;34(15):3290–316.

Tadesse M, Teklie H, Yazew G, Gebreselassie T. Women's Empowerment as a Determinant of Contraceptive use in Ethiopia Further Analysis of the 2011 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. DHS Further Analysis Reports. 2013;82.

Wado YD. Women’s autonomy and reproductive health-care-seeking behavior in Ethiopia. Women Health. 2018;58(7):729–43.

Woldemicael G. Do women with higher autonomy seek more maternal health care? Evidence from Eritrea and Ethiopia. Health Care Women Int. 2010;31(7):599–620.

Yigzaw T, Berhane Y, Deyessa N, Kaba M. Perceptions and attitude towards violence against women by their spouses: a qualitative study in Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2010. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhd.v24i1.62943.

Tiruneh FN, Chuang K-Y, Chuang Y-C. Women’s autonomy and maternal healthcare service utilization in Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):718.

Edhs E. demographic and health survey 2016: key indicators report. DHS Program ICF. 2016;363:364.

Cools S, Kotsadam A. Resources and intimate partner violence in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev. 2017;95:211–30.

Rani M, Bonu S. Attitudes toward wife beating: a cross-country study in Asia. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(8):1371–97.

Haj-Yahia MM. Beliefs about wife beating among Arab men from Israel: the influence of their patriarchal ideology. J Family Viol. 2003;18(4):193–206.

Kim-Goh M, Baello J. Attitudes toward domestic violence in Korean and Vietnamese immigrant communities: Implications for human services. J Family Viol. 2008;23(7):647–54.

Madan M. Understanding attitudes toward spousal abuse: Beliefs about wife-beating justification amongst men and women in India: Michigan State University. Criminal Justice; 2013.

Uthman OA, Lawoko S, Moradi T. Factors associated with attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women: a comparative analysis of 17 sub-Saharan countries. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2009;9(1):14.

García-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts C. WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: World Health Organization; 2005.

Choi SY, Ting K-F. Wife beating in South Africa: An imbalance theory of resources and power. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23(6):834–52.

Vyas S, Heise L. How do area-level socioeconomic status and gender norms affect partner violence against women? Evidence from Tanzania. Int J Public Health. 2016;61(8):971–80.

Alam MS, Tareque MI, Peet ED, Rahman MM, Mahmud T. Female participation in household decision making and the justification of wife beating in Bangladesh. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36(7–8):2986–3005.

Weitzman J, Dreen K. Wife beating: A view of the marital dyad. Soc Casework. 1982;63(5):259–65.

Yodanis CL. Gender inequality, violence against women, and fear: A cross-national test of the feminist theory of violence against women. J Interpers Violence. 2004;19(6):655–75.

Rani M, Bonu S, Diop-Sidibe N. An empirical investigation of attitudes towards wife-beating among men and women in seven sub-Saharan African countries. Afr J Reprod Health. 2004;8:116–36.

Rao V. Wife-beating in rural South India: a qualitative and econometric analysis. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(8):1169–80.

Doku DT, Asante KO. Women’s approval of domestic physical violence against wives: analysis of the Ghana demographic and health survey. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15(1):120.

Ammar NH. Wife battery in Islam: A comprehensive understanding of interpretations. Violence against women. 2007;13(5):516–26.

Chon DS. Muslims, religiosity, and attitudes toward wife beating: analysis of the world values survey. Int Criminol. 2021;1:150–64.

Jung JH, Olson DV. Where does religion matter most? Personal religiosity and the acceptability of wife-beating in cross-national perspective. Sociol Inq. 2017;87(4):608–33.

Oyediran KA, Isiugo-Abanihe UC. Perceptions of Nigerian women on domestic violence: evidence from 2003 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey. Afr J Reprod Health. 2005;9:38–53.

Uthman OA, Moradi T, Lawoko S. Are individual and community acceptance and witnessing of intimate partner violence related to its occurrence? Multilevel structural equation model. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(12):e27738.

Guracho YD, Bifftu BB. Women’s attitude and reasons toward justifying domestic violence in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Afr Health Sci. 2018;18(4):1255–66.

Oyediran KA. Explaining trends and patterns in attitudes towards wife-beating among women in Nigeria: analysis of 2003, 2008, and 2013 Demographic and Health Survey data. Genus. 2016;72(1):1–25.

Faten MR, Sabra MA. Impact of socio-demographic characteristics on attitude of ever married women towards gender based violence in Egypt: secondary analysis of SYPE data, 2014. Med J Cairo Univ. 2018;86:117–22.

Uthman OA, Moradi T, Lawoko S. The independent contribution of individual-, neighbourhood-, and country-level socioeconomic position on attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel model of direct and moderating effects. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(10):1801–9.

Glewwe P, Jacoby HG. Economic growth and the demand for education: is there a wealth effect? J Dev Econ. 2004;74(1):33–51.

Cagney KA, Lauderdale DS. Education, wealth, and cognitive function in later life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57(2):P163–72.

Dubb S. Community wealth building forms: What they are and how to use them at the local level. Acad Manag Perspect. 2016;30(2):141–52.

Kohn M. Community wealth building: lessons from Italy. Community Wealth Building and the Reconstruction of American Democracy: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2020.

Campbell JC. Wife-battering: Cultural contexts versus Western social sciences. Sanctions and Sanctuary. 2019:229–49.

Putra IGNE, Pradnyani PE, Parwangsa NWPL. Vulnerability to domestic physical violence among married women in Indonesia. J Health Res. 2019;33:90–105.

Sardinha L, Catalán HEN. Attitudes towards domestic violence in 49 low-and middle-income countries: a gendered analysis of prevalence and country-level correlates. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(10):e0206101.

Yoshikawa K, Shakya TM, Poudel KC, Jimba M. Acceptance of wife beating and its association with physical violence towards women in Nepal: a cross-sectional study using couple’s data. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e95829.

Dasgupta S. Attitudes about wife-beating and incidence of domestic violence in India: An instrumental variables analysis. J Fam Econ Issues. 2019;40(4):647–57.

Mukamana JI, Machakanja P, Adjei NK. Trends in prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence against women in Zimbabwe, 2005–2015. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2020;20(1):1–11.

Haj-Yahia MM. Beliefs of Jordanian women about wife–beating. Psychol Women Q. 2002;26(4):282–91.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency for providing authorization letter to access EDHS-2016 dataset to conduct this study.

Funding

There is no specific funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA: initiated the research concept, analyze and interpreted the data; GB, ET, BK, AM, ZF, RD, MS, MY, BA, MA, MG, WM, YD: wrote the manuscript; all authors: critically revise, read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have equal participation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from Ethical Review Committee of Wollo University College of Medicine and Health Science. An authorization letter to download EDHS-2016 data set was also obtained from CSA after requesting www.measuredhs.com website. The requested data were treated strictly confidential and was used only for the study purpose. No attempt was done to interact any individual respondent or household included in the survey. Complete information regarding the ethical issue was available in the EDHS-2016 report.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Arefaynie, M., Bitew, G., Amsalu, E.T. et al. Determinants of wife-beating acceptance among reproductive age women in Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis of 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey. BMC Women's Health 21, 342 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01484-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01484-1