Abstract

Background

Cervical cancer is the leading cause of female cancer mortality in Botswana with the majority of cervical cancer patients presenting with late-stage disease. The identification of factors associated with late-stage disease could reduce the cervical cancer burden. This study aims to identify potential patient level clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with a late-stage diagnosis of cervical cancer in Botswana in order to help inform future interventions at the community and individual levels to decrease cervical cancer morbidity and mortality.

Results

There were 984 women diagnosed with cervical cancer from January 2015 to March 2020 at two tertiary hospitals in Gaborone, Botswana. Four hundred forty women (44.7%) presented with late-stage cervical cancer, and 674 women (69.7%) were living with HIV. The mean age at diagnosis was 50.5 years. The association between late-stage (III/IV) cervical cancer at diagnosis and patient clinical and sociodemographic factors was evaluated using multivariable logistic regression with multiple imputation. Women who reported undergoing cervical cancer screening had lower odds of late-stage disease at diagnosis (OR: 0.63, 95% CI 0.47–0.84) compared to those who did not report screening. Women who had never been married had increased odds of late-stage disease at diagnosis (OR: 1.35, 95% CI 1.02–1.86) compared to women who had been married. Women with abnormal vaginal bleeding had higher odds of late-stage disease at diagnosis (OR: 2.32, 95% CI 1.70–3.16) compared to those without abnormal vaginal bleeding. HIV was not associated with a diagnosis of late-stage cervical cancer. Rural women who consulted a traditional healer had increased odds of late-stage disease at diagnosis compared to rural women who had never consulted a traditional healer (OR: 1.61, 95% CI 1.02–2.55).

Conclusion

Increasing education and awareness among women, regardless of their HIV status, and among providers, including traditional healers, about the benefits of cervical cancer screening and about the importance of seeking prompt medical care for abnormal vaginal bleeding, while also developing support systems for unmarried women, may help reduce cervical cancer morbidity and mortality in Botswana.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

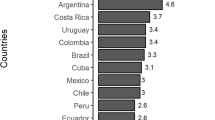

Cervical cancer affects women across the globe, with a disproportionately higher burden of morbidity and mortality in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [1]. In 2018, more than 80% of the 311,000 cervical cancer deaths worldwide occurred in LMICs, predominantly in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [1]. Cervical cancer is classified as a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-related malignancy, further contributing to the increasing cancer burden in SSA countries with a high prevalence of HIV [2]. Additionally, late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis is significantly associated with increased cervical cancer mortality, and approximately 68% of cervical cancers are diagnosed at a late stage in SSA [3]. Thus, it is paramount to detect cervical cancer at an earlier, more treatable stage in order to significantly reduce cervical cancer deaths [4, 5].

Cervical cancer screening aims to prevent invasive cancer [6,7,8,9,10]. Other clinical and sociodemographic factors have been associated with late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis, particularly in LMICS, including abnormal vaginal bleeding [6, 7, 11, 12], age at diagnosis [9, 13,14,15], marital status [6, 15,16,17,18], and living in a rural area [7, 15, 16, 18, 19]. In addition, the practice of traditional healers has been shown to be associated with an increase in late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis [20] and as a barrier to cervical cancer care in low-resource settings [21].

In Botswana, an upper-middle-income country in SSA, cervical cancer is the leading cause of female cancer deaths [22, 23]. However, there remains a dearth of information regarding the demographics and clinical factors that contribute to late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis among women from SSA. Botswana also has a high prevalence of HIV, with 25.1% of females between 15–49 years of age living with HIV in 2019 [24]. In recent decades, with the growing burden of HIV-related cancers [25], the Botswana Ministry of Health and Wellness (MOHW) has prioritized reducing the cervical cancer burden by adapting American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) resource stratified screening strategies for its citizens, with the majority of cervical cancers being detected through loop electrosurgical excision procedure or visual inspection with acetic acid [26,27,28,29]. Despite these efforts by the Botswana MOHW, approximately 50% of cervical cancers are diagnosed at a late stage [6, 30].

This study aims to identify potential clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with a late-stage diagnosis of cervical cancer in Botswana in order to help inform future interventions at the community and individual levels aimed at decreasing cervical cancer morbidity and mortality.

Methods

Study participants

We abstracted data from questionnaires administered during the initial consult visit and medical records for women with invasive cervical cancer who had consented to participate in research studies [30, 31] at Princess Marina Hospital (PMH) and Gaborone Private Hospital (GPH), two tertiary referral hospitals in the capital city of Gaborone, between January 2015 and March 2020 [30, 31]. GPH houses the sole chemo-radiation facility in the country. Women diagnosed at either the public hospital PMH or GPH, are treated at GPH, and their treatment is covered under the government health care system. Women were eligible for this analysis if they were over the age of 18 years, not pregnant, and diagnosed with cervical cancer. Women were excluded if they were diagnosed with cervical carcinoma in situ or if they had recurrent disease.

Covariates

Data collected at the time of cancer diagnosis included patient/sociodemographic and clinical factors (i.e., age, marital status, place of residence, history of cervical cancer screening, ever/never visit with a traditional doctor and/or natural healer, presence of abnormal vaginal bleeding (including post-coital bleeding/bleeding after vaginal intercourse), HIV status, and utilization of antiretroviral therapy (ART)). Additional clinical data was abstracted from medical records regarding clinical factors, such as stage, pathology, and CD4 count. Place of residence was characterized as urban or rural based on the sub-district of the participant’s reported residence [32].

Cervical cancer stage at diagnosis was based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system [33, 34]. FIGO cervical cancer stages were dichotomized as early-stage (I–II) and late-stage (III–IV).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics for each variable of interest were examined for the entire study sample, and by cervical cancer stage at diagnosis (early vs. late). Differences between early- and late-stage disease were examined using Pearson’s chi-squares test for categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test for small sample sizes, and Student t-tests for continuous variables. Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine potential risk factors associated with late- versus early-stage disease. Variables included in the multivariable model were determined based on purposeful selection, review of the literature, and clinical relevance. We assessed missing data, patterns, and reasons for missing data. To account for missing data, we performed multiple imputation with chained equations (MICE) for the multivariable logistic regression model, assuming data were missing at random [35,36,37]. We also conducted complete case analyses (results not shown). We further investigated interactions between HIV status and age and HIV and screening history. We also investigated the use of traditional healers in rural and urban areas using univariate logistic regression. Additionally, because cervical cancer is an AIDS-defining malignancy, we examined clinical and sociodemographic differences between women living with HIV (WLWH) and women without HIV, and performed multivariable analyses stratified by HIV status. For the analysis of WLWH, CD4 count and ART use were included as potential risk factors. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 16, and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval

This study, “Treatment and Outcomes of Patients Presenting with Cancer in Botswana,” was approved by the University of Pennsylvania as part of the Botswana-University of Pennsylvania Partnership (IRB: 820159 IRB#7 Penn) and by the Ministry of Health and Wellness of the Republic of Botswana (HPDME 13/18/1).

Results

Patient characteristics

Between January 2015 and March 2020, 1,007 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer. We excluded 16 women with prior cervical carcinoma in situ and seven women with recurrent disease, resulting in the inclusion of 984 women in this study. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Four hundred forty (44.7%) of the women included in the study were diagnosed with late-stage cervical tumors. The mean age at diagnosis was 50.5 years (range 22.4–95.2), 21.0% (n = 206) lived in urban areas, 65.7% (n = 646) had never been married, 57.4% (n = 539) reported previous cervical cancer screening, 69.7% (n = 674) were WLWH, and 10.1% (n = 95) reported ever having a visited with a traditional healer. Abnormal vaginal bleeding was reported in 73.2% (n = 720) of women, and 87.3% (n = 835) of the cervical cancers were squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) pathology. Women diagnosed at a late stage were less likely to report prior screening (50.8% vs. 63.2%, p < 0.001) and were also more likely to report abnormal vaginal bleeding (82.3% vs. 66.3%, p < 0.001).

Factors associated with late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis

Table 2 displays factors significantly associated with late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis in the imputed multivariable model. MICE was performed to account for missing data for the variables: stage at diagnosis (n = 43), age (n = 1), place of residence (n = 3), marital status (n = 1), screening history (n = 45), HIV status (n = 17), and visit with a traditional healer (n = 27). Never being married (OR: 1.35, 95% CI 1.02–1.86) and experiencing abnormal vaginal bleeding (OR: 2.32, 95% CI 1.70–3.16) had an increased odds of late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis, while previous cervical cancer screening was associated with decreased odds of late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis (OR: 0.65, 95% CI 0.49–0.85). Results from the complete case analysis were analogous to the MICE results. No significant interactions were observed between HIV status and age or between HIV status and screening history.

There were no significant associations between living in an urban residence versus living in a rural residence and having ever visited a traditional healer and having late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis in the multivariable model. However, in our cohort, more rural women than urban women (11% vs. 5%) had consulted with a traditional healer. Table 3 shows the association of presenting with late- versus early-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis when visiting a traditional healer among women living in a rural residence (OR: 1.61, 95% CI 1.02–2.55). This increased probability was not observed among women living in an urban area when visiting a traditional healer.

Characteristics by HIV status

Table 4 shows patient characteristics by HIV status. Of the 984 cervical cancer cases, the HIV status of 967 (98.3%) women was known. Women whose HIV status was unknown (n = 17) were excluded from the HIV stratified analyses. WLWH comprised 69.7% (n = 674) of the study population and were significantly younger than women without HIV (45.8 years vs. 60.5 years, p < 0.001). WLWH were also more likely to live in urban areas (24.0% vs. 14.7%, p = 0.001), were more likely to have never been married (74.0% vs. 47.8%, p < 0.001), and were more likely to have been screened for cervical cancer (61.8% vs. 48.4%, p < 0.001) than women without HIV. In addition, WLWH were more likely to have SCC pathology than women without HIV (88.9% vs. 83.7%, p = 0.020). Among the WLWH, 78.6% (n = 429) had a CD4 cell count > 250 cells/mm3 at diagnosis, and 96.2% (n = 640) reported being on ART.

Table 5 shows the results of the multivariable logistic regression models by HIV status. Among the WLWH, prior cervical cancer screening showed decreased odds with late-stage disease at diagnosis (OR: 0.61, 95% CI 0.44–0.86), and increased odds with previous abnormal bleeding symptoms (OR: 2.10, 95% CI 1.46–3.01). Among women without HIV, factors associated with higher odds of late-stage disease at diagnosis included increasing age (OR: 1.02, 95% CI 1.00–1.14; p = 0.041) and abnormal vaginal bleeding (OR: 3.06, 95% CI 1.52–5.71). Results of complete case analyses by HIV status were similar to the imputed results.

Discussion

This large study of women with cervical cancer in Botswana aimed to identify potential clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with a late-stage diagnosis of cervical cancer in Botswana. Our study showed that prior cervical cancer screening was associated with decreased odds of having late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis, whereas experiencing abnormal vaginal bleeding and having never been married were associated with an increased odds of having late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis. Having HIV was not associated with having late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis. Furthermore, results suggested that women living in rural areas who visited a traditional healer were more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage cervical cancer.

Screening has been shown to lead to an earlier diagnosis of cervical cancer in high-income countries with established screening programs, and screening has also been shown to be effective in low resource settings [7, 9, 38]. With the growing burden of HIV-related cancers in recent decades [25], the Botswana MOHW has prioritized reducing the cervical cancer burden through implementing and supporting a national cervical cancer screening program as part of the HIV care continuum [23, 27, 28, 39, 40]. A prior retrospective study by Nassali et al. (2018) reviewed 149 cervical cancer patients admitted to PMH from August 2016 to February 2017, which may include some overlap with our study sample. In that study, Nassali et al. defined late-stage cervical cancer as FIGO stage IB2-IVB, and found an increased odds of presenting with late-stage tumors in patients not previously screened for cervical cancer. Additionally, two qualitative studies in Botswana [41, 42] have shown that lack of knowledge regarding the benefits of screening for cervical cancer can delay diagnosis. Our study provides further evidence supporting the finding that screening decreases the odds of presenting with late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis when implemented in a low resource setting.

Early-stage asymptomatic cervical cancer can be detected through screening, but in the absence of screening, patients with cervical cancer can present with clinical symptoms including abnormal vaginal bleeding and post-coital bleeding [34]. Reports of symptomatic bleeding and its association with late-stage disease at diagnosis in low resource settings have been inconsistent in the literature [6, 7, 11, 12]. Studies have shown an increased risk [6], no association [7], and a decreased risk [11, 12]. In Nepal, a decreased risk for having late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis was noted if the symptoms of bleeding were reported first to the woman’s husband, who might encourage his wife to seek medical care. In Morocco, the decreased association between having late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis and having symptomatic bleeding was hypothesized to be due to understanding the severity of bleeding as a cervical cancer symptom and seeking medical care without delay. Two studies in Botswana [20, 43] showed that the perception of symptom severity was related to having advanced stage cervical cancer at diagnosis and to having a delay in health seeking behavior. In our study, reporting gynecological bleeding symptoms, including previous abnormal vaginal bleeding and/or post-coital bleeding, was associated with a two-fold increase in the odds of presenting with late-stage cervical cancer. These results support increasing awareness regarding abnormal vaginal bleeding and post-coital bleeding as indications of cervical cancer and emphasizing the need to seek medical care as soon as possible. In addition, these findings support screening asymptomatic women to be able to diagnose cervical cancer at an early stage.

In our study, there was no significant difference between WLWH and women without HIV with regard to their likelihood of presenting with advanced stage cervical cancer. Some studies have recognized HIV as a risk factor for late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis [16, 19], yet other studies [6, 44] have reported no association with HIV and late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis. The role of HIV in the diagnosis of late-stage cervical cancer remains unclear and should be investigated further. When comparing WLWH and women without HIV in our cohort, the WLWH were younger, were more likely to have undergone cervical cancer screening, had more often lived in urban areas, and were more likely to be married or to have been married than women without HIV. Also, in the subgroup analyses, associations with late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis differed between the two subgroups of WLWH versus women without HIV. Increasing age was significantly associated with late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis in women without HIV, but not in WLWH. WLWH with a history of cervical cancer screening had lower odds of presenting with late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis; however cervical cancer screening was not significantly associated with late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis in women without HIV. In Botswana, cervical cancer screening programs have been implemented as part of the HIV care continuum for women, making it is plausible that women without HIV do not access screening services to the same extent as WLWH. Therefore, increasing screening services among women without HIV could reduce the prevalence of late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis for these women.

Our study saw a decrease in late-stage cervical cancer cases among women who had been married. Similarly, a study from Nepal [11] noted that married women with symptomatic bleeding were less likely to present with a late-stage cervical cancer because husbands may encourage their wives to seek medical care. A study by Ibrahimi and Pinheiro (2017) in the United States reported that being married was an independent predictor of a more favorable prognosis of cervical cancer [45]. While some studies have identified being unmarried as a risk factor for having late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis [6, 17, 18], other studies have found no such association [15, 16]. Reasons for this association are unclear. Future studies investigating differences in financial, emotional, and sociocultural marital structures and the impact on prompt cancer diagnosis are warranted. These inconsistencies could be attributed to differences among the sociocultural marital structures and support systems across countries, which need to be explored further.

Areas of residence may also impact health care. For example, living in a rural area versus living in an urban area has been investigated as a potential contributing factor for women with late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis [7, 15, 16, 18, 19]. A study in Sudan reported that an increased risk for having late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis was associated with living in a rural setting versus living in an urban setting [15], but this result was not seen in our cohort, nor was any such association reported in other studies in Ghana [7], Florida [18], Ethiopia [19], or SSA [15]. The use of traditional healers has been shown to be associated with late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis in Botswana [20] and as a barrier to cervical cancer care in Uganda [21]. In Botswana, over 95% of traditional healers live in rural areas [46], and thus women living in a rural area may be more likely to consult with traditional healers as their first choice for healthcare. In our study, when examining only women living in a rural area, those who visited a traditional healer had a higher odds of presenting with late-stage cervical cancer. Points of intervention in rural areas could include educating traditional healers to recognize symptoms of cervical cancer in order to facilitate a referral for diagnosis and treatment.

This large study investigating late-stage cervical cancer at diagnosis in Botswana includes detailed demographic and clinical information on patients in Botswana collected over a five-year period, but it does have several potential limitations and challenges. It is important to note that, due to the cross-sectional study design, no decisive conclusions can be made about the temporality or causality among the study variables and late stage diagnosis. Patients were enrolled at PMH, a public tertiary hospital with oncology services, and at GPH, a private tertiary hospital with the only chemo-radiation oncology center in Botswana; thus, all patients who need radiotherapy should be sent to GPH. We were unable to account for patients who were not diagnosed with or treated for cervical cancer outside of these two facilities. In addition, the study collected data at the time of diagnosis and is therefore subject to recall bias, social desirability bias, and potential unmeasured confounding and missing data. Unfortunately, due to the retrospective nature of the study, we lacked important information and were unable to account for confounders including education level, knowledge and awareness of cervical cancer, and cervical cancer screening. To account for any bias due to missing data, we conducted MICE for the primary analysis [35,36,37]. Results using MICE were similar to the complete case analysis. Although our findings represent a large proportion of cervical cancer cases in Botswana, they do not represent all cervical cancer patients in Botswana and are not generalizable to the entire country.

Conclusion

Our results highlight patient level factors associated with late-stage cervical at diagnosis and indicate potential areas for intervention to mitigate the cervical cancer burden in Botswana. Our findings show that cervical cancer screening for women in Botswana is associated with the early detection of cervical cancer, particularly in women with HIV. Future efforts to include women without HIV and women who have not been married in cervical cancer screening efforts could result in the earlier detection of cervical cancer in these groups. Future early cervical cancer detection efforts should emphasize cancer symptom awareness and early detection through cervical cancer screening, and should also include traditional healers in the cancer care continuum.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due identifying information, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Pineros M, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(8):1941–53.

Olorunfemi G, Ndlovu N, Masukume G, Chikandiwa A, Pisa PT, Singh E. Temporal trends in the epidemiology of cervical cancer in South Africa (1994–2012). Int J Cancer. 2018;143(9):2238–49.

Sengayi-Muchengeti M, Joko-Fru WY, Miranda-Filho A, Egue M, Akele-Akpo MT, N'da G, et al. Cervical cancer survival in sub-Saharan Africa by age, stage at diagnosis and Human Development Index: a population-based registry study. Int J Cancer. 2020.

Battista RN, Grover SA. Early detection of cancer: an overview. Annu Rev Public Health. 1988;9:21–45.

Adanu RM. Cervical cancer knowledge and screening in Accra, Ghana. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11(6):487–8.

Nassali MN, Tadele M, Nkuba RM, Modimowame J, Enyeribe I, Katse E. Predictors of locally advanced disease at presentation and clinical outcomes among cervical cancer patients admitted at a tertiary hospital in Botswana. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2018;28(6):1218–25.

Dunyo P, Effah K, Udofia EA. Factors associated with late presentation of cervical cancer cases at a district hospital: a retrospective study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1156.

Force USPST, Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, et al. Screening for Cervical Cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320(7):674–86.

Priest P, Sadler L, Sykes P, Marshall R, Peters J, Crengle S. Determinants of inequalities in cervical cancer stage at diagnosis and survival in New Zealand. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(2):209–14.

Brewer N, Pearce N, Jeffreys M, Borman B, Ellison-Loschmann L. Does screening history explain the ethnic differences in stage at diagnosis of cervical cancer in New Zealand? Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(1):156–65.

Gyenwali D, Pariyar J, Onta SR. Factors associated with late diagnosis of cervical cancer in Nepal. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(7):4373–7.

Berraho M, Obtel M, Bendahhou K, Zidouh A, Errihani H, Benider A, et al. Sociodemographic factors and delay in the diagnosis of cervical cancer in Morocco. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;12:14.

Mwaka AD, Garimoi CO, Were EM, Roland M, Wabinga H, Lyratzopoulos G. Social, demographic and healthcare factors associated with stage at diagnosis of cervical cancer: cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital in Northern Uganda. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e007690.

SEER N. Cancer Stat Facts: Breast Cancer 2017 [Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast-subtypes.html.

Ibrahim A, Rasch V, Pukkala E, Aro AR. Predictors of cervical cancer being at an advanced stage at diagnosis in Sudan. Int J Womens Health. 2011;3:385–9.

Stewart TS, Moodley J, Walter FM. Population risk factors for late-stage presentation of cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;53:81–92.

Saghari S, Ghamsary M, Marie-Mitchell A, Oda K, Morgan JW. Sociodemographic predictors of delayed- versus early-stage cervical cancer in California. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(4):250–5.

Ferrante JM, Gonzalez EC, Roetzheim RG, Pal N, Woodard L. Clinical and demographic predictors of late-stage cervical cancer. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(5):439–45.

Begoihn M, Mathewos A, Aynalem A, Wondemagegnehu T, Moelle U, Gizaw M, et al. Cervical cancer in Ethiopia—predictors of advanced stage and prolonged time to diagnosis. Infect Agent Cancer. 2019;14:36.

Anakwenze C, Bhatia R, Rate W, Bakwenabatsile L, Ngoni K, Rayne S, et al. Factors related to advanced stage of cancer presentation in Botswana. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–9.

Mwaka AD, Okello ES, Orach CG. Barriers to biomedical care and use of traditional medicines for treatment of cervical cancer: an exploratory qualitative study in northern Uganda. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2015;24(4):503–13.

Botswana National Cancer Registry. http://afcrn.org/membership/members/118-bncr.

Johnson LG, Ramogola-Masire D, Teitelman AM, Jemmott JB, Buttenheim AM. Assessing nurses’ adherence to the see-and-treat guidelines of Botswana’s National Cervical Cancer Prevention Programme. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2020;13(3):329–36.

UNAIDS. Country factsheets. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/botswana.

Dryden-Peterson S, Medhin H, Kebabonye-Pusoentsi M, Seage GR 3rd, Suneja G, Kayembe MK, et al. Cancer incidence following expansion of HIV treatment in Botswana. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0135602.

Ramogola-Masire D, de Klerk R, Monare B, Ratshaa B, Friedman HM, Zetola NM. Cervical cancer prevention in HIV-infected women using the “see and treat” approach in Botswana. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(3):308–13.

Grover S, Raesima M, Bvochora-Nsingo M, Chiyapo SP, Balang D, Tapela N, et al. Cervical cancer in Botswana: current state and future steps for screening and treatment programs. Front Oncol. 2015;5:239.

Barchi F, Winter SC, Ketshogile FM, Ramogola-Masire D. Adherence to screening appointments in a cervical cancer clinic serving HIV-positive women in Botswana. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):318.

Jeronimo J, Castle PE, Temin S, Denny L, Gupta V, Kim JJ, et al. Secondary prevention of cervical cancer: ASCO resource-stratified clinical practice guideline. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3(5):635–57.

Grover S, MacDuffie EC, Wang Q, Bvochora-Nsingo M, Bhatia RK, Balang D, et al. HIV infection is not associated with the initiation of curative treatment in women with cervical cancer in Botswana. Cancer. 2019;125(10):1645–53.

Grover S, Chiyapo SP, Puri P, Narasimhamurthy M, Gaolebale BE, Tapela N, et al. Multidisciplinary gynecologic oncology clinic in Botswana: a model for multidisciplinary oncology care in low- and middle-income settings. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3(5):666–70.

Botswana Demographics. https://www.statsbots.org.bw/guide-villages-botswana.

Bhatla N, Berek JS, Cuello Fredes M, Denny LA, Grenman S, Karunaratne K, et al. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;145(1):129–35.

Cohen PA, Jhingran A, Oaknin A, Denny L. Cervical cancer. Lancet. 2019;393(10167):169–82.

Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393.

White IR, Daniel R, Royston P. Avoiding bias due to perfect prediction in multiple imputation of incomplete categorical variables. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2010;54(10):2267–75.

White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–99.

Sankaranarayanan R. Screening for cancer in low- and middle-income countries. Ann Glob Health. 2014;80(5):412–7.

Raesima MM, Forhan SE, Voetsch AC, Hewitt S, Hariri S, Wang SA, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among school girls in a demonstration project—Botswana, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(40):1147–9.

Castle PE, Varallo JE, Bertram MM, Ratshaa B, Kitheka M, Rammipi K. High-risk human papillomavirus prevalence in self-collected cervicovaginal specimens from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative women and women living with HIV living in Botswana. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(2):e0229086.

Mingo AM, Panozzo CA, DiAngi YT, Smith JS, Steenhoff AP, Ramogola-Masire D, et al. Cervical cancer awareness and screening in Botswana. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22(4):638–44.

Matenge TG, Mash B. Barriers to accessing cervical cancer screening among HIV positive women in Kgatleng district, Botswana: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(10):e0205425.

Bhatia RK, Rayne S, Rate W, Bakwenabatsile L, Monare B, Anakwenze C, et al. Patient factors associated with delays in obtaining cancer care in Botswana. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–13.

Wu ES, Urban RR, Krantz EM, Mugisha NM, Nakisige C, Schwartz SM, et al. The association between HIV infection and cervical cancer presentation and survival in Uganda. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2020;31:100516.

El Ibrahimi S, Pinheiro PS. The effect of marriage on stage at diagnosis and survival in women with cervical cancer. Psychooncology. 2017;26(5):704–10.

Tapera R, Moseki S, January J. The status of health promotion in Botswana. J Public Health Afr. 2018;9(1):699.

Acknowledgements

We thank Princess Marina Hospital, Gaborone Private Hospital, the Botswana Ministry of Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for their constant support, and all of our patients, who made this study possible.

Funding

Mentored Patient Oriented Career Research Development Award (1-K08CA230170-01A1 to SG), Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Pennsylvania, and Sub-Saharan African Collaborative HIV and Cancer Consortia-U54 (1U54 CA190158-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TFK, NM, DW, TRR, AMM, and SG conceived the study and design. SG and BM facilitated acquisition of the data. TFK, NM, and AMM analyzed the data. TFK, NM, DW, TRR, AMM, and SG interpreted the data. TFK drafted the manuscript. TFK, RL, LBM, TBR, BM, MNN, DRM, MB, NM, DW, TRR, AMM, and SG provided critical review and final approval of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study, “Treatment and Outcomes of Patients Presenting with Cancer in Botswana,” was approved by the University of Pennsylvania as part of the Botswana-University of Pennsylvania Partnership (IRB: 820159 IRB#7 Penn) and by the Ministry of Health and Wellness of the Republic of Botswana (HPDME 13/18/1). Informed consent was obtained from all of the study participants for participation in “Treatment and Outcomes of Patients Presenting with Cancer in Botswana”. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (Declaration of Helsinki).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Friebel-Klingner, T.M., Luckett, R., Bazzett-Matabele, L. et al. Clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with late stage cervical cancer diagnosis in Botswana. BMC Women's Health 21, 267 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01402-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01402-5