Abstract

Background

Racial and ethnic inequities in palliative care are well-established. The way researchers design and interpret studies investigating race- and ethnicity-based disparities has future implications on the interventions aimed to reduce these inequities. If racism is not discussed when contextualizing findings, it is less likely to be addressed and inequities will persist.

Objective

To summarize the characteristics of 12 years of academic literature that investigates race- or ethnicity-based disparities in palliative care access, outcomes and experiences, and determine the extent to which racism is discussed when interpreting findings.

Methods

Following Arksey & O’Malley’s methodology for scoping reviews, we searched bibliographic databases for primary, peer reviewed studies globally, in all languages, that collected race or ethnicity variables in a palliative care context (January 1, 2011 to October 17, 2023). We recorded study characteristics and categorized citations based on their research focus—whether race or ethnicity were examined as a major focus (analyzed as a primary independent variable or population of interest) or minor focus (analyzed as a secondary variable) of the research purpose, and the interpretation of findings—whether authors directly or indirectly discussed racism when contextualizing the study results.

Results

We identified 3000 citations and included 181 in our review. Of these, most were from the United States (88.95%) and examined race or ethnicity as a major focus (71.27%). When interpreting findings, authors directly named racism in 7.18% of publications. They were more likely to use words closely associated with racism (20.44%) or describe systemic or individual factors (41.44%). Racism was directly named in 33.33% of articles published since 2021 versus 3.92% in the 10 years prior, suggesting it is becoming more common.

Conclusion

While the focus on race and ethnicity in palliative care research is increasing, there is room for improvement when acknowledging systemic factors – including racism – during data analysis. Researchers must be purposeful when investigating race and ethnicity, and identify how racism shapes palliative care access, outcomes and experiences of racially and ethnically minoritized patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Significant racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care access and outcomes [1,2,3]. For example, racialized patients have been found to have decreased access to culturally appropriate palliative care [4,5,6], and unequal access to symptom management medications resulting in worse pain management [7,8,9]. Research from the United States (US) shows that when accessed, racialized groups are more likely to disenroll from hospice [10,11,12]. Researchers are being encouraged to include analyses of racism when investigating and explaining disparities [13] as an acknowledgement that health inequities experienced by racialized and ethnically minoritized people are “rooted in racism shaped by the legacies of slavery, indentured servitude, colonialism, imperialism, war, ultra-nationalism, ethnic absolutism, xenophobia and hate speech” [14]. Some palliative care journals now require researchers who include race as a variable to explicitly “address structural racism, calling it out by name, and identifying the form it takes” when interpreting findings [15].

The manner in which researchers interpret their findings holds the power to shape future interventions that reduce and eliminate disparities: the root causes posited by researchers to explain health disparities or their determinants are more likely to be investigated in subsequent research studies. In turn, these inform the evidence-based interventions and policy changes designed to reduce or eliminate disparities [16, 17]. To make substantive contributions to reducing disparities in palliative care, researchers investigating race and ethnicity have a responsibility to name and discuss the role of racism when interpreting their findings. If racism is not named as a root cause, it is less likely to be addressed, and inequities will persist [14]. Despite the recognized value of naming racism, little is known about how often, if at all, systemic and interpersonal racism are named in the contextualization of findings in palliative care disparities research.

Our study aims to summarize the characteristics of 12 years of academic literature that investigates race- or ethnicity-based disparities in palliative care access, outcomes and experiences, and determine the extent to which racism is discussed when interpreting findings.

Terminology

To position this research, the concepts of race, ethnicity, and racism need to be defined and contextualized (Table 1). Race is a social construct [14] created to facilitate the exploitation and abuse of people experiencing colonization by European imperialist nations [18]. As a social construct, race has no bearing on biological differences and is not due to genetic variations [19]; therefore, health disparities do not result from race itself, but rather from the experiences of racism at multiple societal levels [20]. The exact definitions, meanings, and categories pertaining to race can change depending on the larger context (e.g., the same person may be identified as different races in different countries). Some countries do not widely discuss race at all, but discrimination based on colourism or ethnic group may occur [21,22,23]. The present-day concepts of race and racism used in this review are drawn from the definitions describing power relationships rooted in colonial legacies and practices which may not be ubiquitous or consistently conceptualized across all countries. Ethnicity is a grouping of people based on shared history, territory, or culture, and does not specifically include race. Because many citations included in this review erroneously used these terms interchangeably, we often refer to them together, acknowledging the limitations of this approach.

Racism broadly refers to conscious or unconscious oppression, inferior treatment, or lower status assigned to a racialized or ethnically minoritized individual or group [24]. Systemic racism, structural racism, and institutional racism are related but distinct terms that refer to racism embedded within the fabric and structures of society, policies, and institutions [24, 25]. These manifestations of racism differ from interpersonal racism, which occurs between two or more individuals [26].

Methods

Research design

We followed Arksey & O’Malley’s methodology for scoping reviews [29]. Compared to systematic reviews, which critically appraise and synthesize evidence to answer a single or precise research question, scoping reviews concentrate on an overall body of literature and can be used to examine how research is conducted on a certain topic [30]. We felt that a scoping review methodology best aligned with our study aim to summarize the investigation and interpretation of research that contributes to detecting and understanding race- and ethnicity- based disparities in palliative care. We describe our review following the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) reporting [31].

Procedure

Identifying relevant literature

In consultation with an Information Specialist, we designed a search strategy to be applied across multiple bibliographic databases for publications between January 1, 2011 and October 17, 2023. We searched bibliographic databases focused on medicine and healthcare (CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PubMed, Cochrane) for terms broadly centered around palliative care, race and ethnicity. We selected broad terms to increase the potential of identifying articles that may refer to these concepts using different terms. A comprehensive list of databases and search terms are in Additional file 1. We ran the initial search in July, 2021, and two subsequent searches in August 2022 and October 2023. While we did not include reviews in our analysis, we did hand–search the reference list for review studies that passed title and abstract screening.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We conducted a broad, comprehensive search, not limiting inclusion to any disease, country of origin, or language of publication. We structured our inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2) to focus on peer-reviewed studies that contributed to detecting or understanding race- or ethnicity-based disparities related to palliative care access, outcomes or experiences. During the screening phases, we evaluated each citation and included studies that (1) took place within a palliative care context (i.e., care was delivered in a palliative or hospice program, or by a palliative care or hospice provider); (2) collected and analyzed race or ethnicity as an independent variable, or used a race or ethnicity to define a study population or cohort; and (3) was peer-reviewed and evaluated primary data. Because our review focused on articles that describe and explain disparities, we excluded articles that evaluated interventions to reduce disparities as these primarily focus on solving a problem, not describing it.

Title and abstract screen

Two of three reviewers (KA, AK, JW) independently screened each title and abstract to assess eligibility. Differences were resolved through discussion, or assessment by a third reviewer. When it was unclear whether an article met criteria, it was included in the full text screening. If an article title appeared relevant but an abstract was not available, we included it in the full review. All articles in other languages had abstracts available in English; none of these articles were included in the full text screen.

Full text screen

The full text of eligible citations was screened using the same criteria as above and review articles were excluded. We hand–screened the reference lists from review articles that passed the title and abstract screen phase to identify any additional eligible citations.

Charting the data

During data abstraction, two independent reviewers (KA and AK) both recorded information for the first 45 articles, ensuring a common understanding. One reviewer (KA or AK) abstracted data for the remaining citations, and each reviewed the other’s data at the end of the abstraction process. Using a standardized form (Additional file 2) for each citation we documented: first author, title, publication year, location, study purpose, study outcomes, races or ethnicities collected, and whose race or ethnicity was collected.

We initially captured nine categories for race and ethnicity including ‘other: please specify’. Following a review of the free–text responses provided in the ‘other’ category, we created five additional categories and reclassified ‘other’ responses accordingly. These include Asian/Pacific Islander, Turtle Island (North American) Indigenous, Aboriginal Australian, Māori, and Mixed race. The new ‘other’ category captured instances when researchers included an ‘other’ option, or when they included an exclusionary group (e.g. “non-Hispanic”, “non-White”, “none of the above”, etc.).

The study team observed a great degree of heterogeneity among the included articles. In line with scoping review methodology, which affords an iterative approach to data analysis with increasing familiarity of the literature [32, 33], we further classified studies based on whether the examination of race or ethnicity was the major or minor focus of the research purpose (research focus), and whether authors directly or indirectly discuss racism when interpreting their findings (interpretation of findings). The operationalization of these variables is described below and in Table 3.

Research focus

We reviewed the study purpose and classified studies as having a ‘major focus’ if race or ethnicity were named in the study purpose, and the study was designed to (a) evaluate associations between palliative care access, outcomes or experiences and patient or provider race or ethnicity, or (b) investigate the experiences of patients or providers representing a specific racial or ethnic population. We classified studies as ‘minor focus’ if race or ethnicity were not named in the study purpose, and the study was designed to evaluate associations between palliative care access, outcomes or experiences and a variable other than race or ethnicity, but race or ethnicity were analyzed as one of several secondary characteristics or variables.

Interpretation of finding

We reviewed the discussion section of each article for mention of racism according to four binary variables ranging from direct to indirect: (1) named racism (yes/no), (2) used a keyword associated with racism (yes/no), (3) described systemic or individual provider factors (yes/no), or (4) none (yes/no). To determine if authors explicitly named racism or used a keyword, we conducted a text search for the terms racis*, bias, discriminat*, systemic, prejudic*, or stereotype. We reviewed the use of each term in context to verify it pertained to disparities. These keywords were selected based on concepts presented in previously published author guidelines and recommendations for palliative care research that includes the examination of race, as well as closely related synonyms [15, 20]. Next, we looked for text describing systemic or individual provider factors that may impact racially or ethnically minoritized individuals. For example, describing differential access to healthcare resources in neighborhoods serving predominantly racially minoritized patients (including hospital funding or staffing); opiate prescribing patterns by physicians; comments on cultural sensitivity; historical trauma resulting in patient mistrust; institutional policies, practices and regulations; or social determinants of health. These factors impact racially or ethnically minoritized individuals and are often associated with systemic racism (including structural and institutional racism) and interpersonal/individual racism (including prejudice or bias). Finally, citations that did not use any of these were marked as yes for ‘none’.

Data analysis

We summarized study characteristics as well as the distribution of articles by research focus and interpretation of findings as overall counts and percentages. We evaluated changes in research focus and interpretation of findings over time by counting the number of citations in each category year by year. Finally, we explored the relationship between research focus and interpretation of findings by visualizing the flow of citations from research focus across variables, from indirect to direct references to racism.

Results

We identified 3000 articles (See PRISMA diagram in Fig. 1). Following title and abstract screening, 368 articles remained and were included in the full text screening. The final review includes 181 articles, whose characteristics are detailed in Table 4.

As seen in Table 5, almost 90% of studies were conducted in the United States of America (US) followed by Australia and Canada, each contributing 3.1% of studies. The top four categories of race or ethnicity utilized were White (81.22% of studies), followed by Black (73.48%), Latinx/Hispanic (53.59%), and Other (53.04%). Nearly two thirds (74.03%) of studies included four or fewer categories for race or ethnicity, and 93.48% focused on the race or ethnicity of the patient or caregiver.

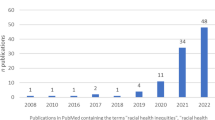

Research focus and interpretation of findings by year. A Number of citations where race or ethnicity were the major focus or minor focus of the stated research purpose by year. B Number of citations that named racism, used a keyword, described systemic or individual provider factors, or none by year. Keywords include ‘bias’, ‘discriminat*’, ‘systemic’, ‘prejudic*’, and ‘stereotype’. Percent is calculated using the number of citations for that year as the denominator. 2023 includes up to October 17, 2023, only

Race or ethnicity were a major focus of most studies (71.27%). The proportion of studies with major focus on race or ethnicity fluctuated from year to year with a low of 50% of articles in 2016, and a high of 100% of articles in 2013 (Fig. 2A). Within the discussion sections, authors described systemic or individual provider factors (41.44%) more often than they used a keyword (20.44%). Only a small portion (7.18%) directly named racism. The number of studies that discussed racism, either directly or indirectly, steadily increased since 2018, although the total number annually remains low (Fig. 2B): In 2013, 27% of articles discussed racism and this has gradually increased to 64% of articles in 2023. Since 2021, authors of 11 out of 33 articles (33.33%) directly named racism when interpreting findings representing an increase from the previous ten years (2011–2020), in which only two out of 51 articles (3.92%) directly named racism.

Intersection between research focus and interpretation of findings

Figure 3 shows the flow of studies from their focus on the left across the various forms of acknowledging racism in the interpretation of findings. Articles with a major focus on race or ethnicity were more likely to discuss racism directly or indirectly. Of the 13 studies that directly named racism, 12 (92.31%) included the examination of race or ethnicity as a major focus of their research questions. Similarly, 32 of 37 (86.49%) studies that used a keyword and 64 of 75 (85.33%) studies that described systemic or individual provider factors started with race or ethnicity as a major focus of their research question. If authors directly discussed racism in their findings, it is likely that they also did so indirectly: 12 of 13 (92.31%) articles that named racism also used a keyword, and 29 of 37 (78.38%) articles that used a keyword also described systemic or individual provider factors.

Sankey diagram of citations by research focus and interpretation of findings. This sankey diagram shows the flow of citations from research focus (whether race or ethnicity were a major or minor focus of the stated research objective) across interpretation of findings, from indirect to direct. The colour of the path indicates research focus: Blue paths denote citations that had a major focus on race or ethnicity, and grey paths denote citations that had a minor focus on race or ethnicity. Keywords include ‘bias’, ‘discriminat*’, ‘systemic’, ‘prejudic*’, or ‘stereotype’. Percents are calculated using the size of the sample ( n = 181) as the denominator.

Discussion

In this study examining if and how palliative care researchers discuss racism when contextualizing their findings, we observed that only 7.18% of studies directly named racism in their discussions despite 71.27% including race or ethnicity as a major focus of their research purpose.

Overall, the paucity of explicit discourse on racism in the palliative care literature we reviewed mirrors the general medical literature where the word “racism” appeared in less than 1% of articles in four of the highest impact general medical journals [209]. Low rates of the word “racism” observed in our findings could have several explanations. Researchers may not have considered systemic or interpersonal racism as causes for the observed outcomes. Although the use of the word racism was low, authors more often described systemic or individual provider factors. It is possible that researchers directly or indirectly discuss racism within their interpretations, but were censored or encouraged to ‘soften their language’ by medical journal reviewers or editors in order to make arguments more palatable to scientific audiences [210].

The time trends visualizing the proportion of articles that directly or indirectly discuss racism exhibits two peaks in 2012 and 2022–2023 that seem to coincide with societal events and subsequent movements that brought discussions of race and racism to the fore, particularly in the United States and Canada. The murders of Trayvon Martin in 2012 and George Floyd in 2020—Black men in the US—and the confirmation of mass unmarked graves at Canadian residential schools in 2021—government-sponsored schools designed to assimilate Indigenous children who were subjected to neglect, medical experimentation and abuse [211]—each spurred social movements, including Black Lives Matter, and increased societal awareness of inequities and injustices faced by racialized people. As well, many racialized communities had higher case fatality rates during the COVID-19 pandemic, drawing additional attention to existing health and social inequities for racialized people [212,213,214]. Since 2020, advocacy for racial equality has prompted governments, health care institutions, academic organizations, and medical journals to create new policies and standards [215,216,217] – including the importance of naming and discussing racism in health disparities research, which may explain the upward and seemingly sustained trend we observed over the past three years.

Examining the flow of citations across research focus and interpretation of findings, we found that authors were more likely to directly or indirectly discuss racism when contextualizing their findings if race or ethnicity were a major focus of a study, and that more direct references to racism were less common than indirect references to racism. This may indicate that researchers with greater understanding of the root causes of inequities for racialized and ethnically minoritized groups are more likely to design research focused on detecting and describing race- and ethnicity-based disparities in palliative care, and more likely to articulate these factors in the interpretation of their findings.

We found little diversity in the representation of studies in both the races or ethnicities that were researched, nor in the geographic location of the research. First, most studies examined outcomes for people who were White, suggesting that this population may have been used as a comparator group. This approach has been criticized for centering Whiteness and placing many diverse groups within the Other [178] and perpetuating a broader system where White race is considered normative, and outcomes for individual racialized groups are obscured [218]. While White, Black, Hispanic/LatinX groups were examined in more than 50% of citations, others –– including Turtle Island (North American) Indigenous, Aboriginal Australian, Asian (multiple groups), Asian/Pacific Islander, Mixed, Māori, South Asian, East Asian, and Southeast Asian – were named in 25% or fewer studies. This lack of representation highlights groups that could potentially benefit from more focus in palliative care research (for example Southeast Asian, East Asian, South Asian, Indigenous groups, West Asian/Middle Eastern, mixed race etc.).

Second, a vast majority of the identified studies originated in the US with little representation from other countries. This finding suggests a significant overrepresentation of US-based studies when compared with published palliative care research, generally. A recent bibliometric review and mapping analysis of international palliative care research reported that the US represented 31.53% of articles, followed by the UK (12.58%), Canada (8.26%) and Australia (6.25%) [219]. This paucity of geographic diversity may indicate differing conceptualizations of race or ethnicity between countries. Previous research suggests that the US may be overrepresented in the area of racial or ethnic disparities research because the concept of race is legally defined and frequently collected, making this data more available to researchers [220]. While the concept of race and ethnicity can vary geographically and there may be challenges with data collection in some jurisdictions, it remains important to pursue research in geographically underrepresented locations. Research is a key foundational component of improving national palliative care systems [221, 222], therefore it is imperative that research from under-represented populations and countries be supported and prioritized. Supports may include increasing funding available for research [222], establishing peer-reviewed publication targets [221], and cultivating national and international congresses or scientific meetings that prioritize palliative care research, facilitate capacity building, and encourage the formation of collaborative relationships between different sectors and countries [219, 221].

Limitations

First, because race is socially constructed, its definitions, meanings, and racial categories themselves can change depending on the larger context. Researchers will therefore conceptualize race based on their own setting, which may result in some knowledge being missed by our search strategy. Similarly, concepts may have different names in different languages and studies in languages other than English may have not been captured in our search for this reason.

Second, when analyzing study characteristics, we adopted racial and ethnic categories consistent with those used in the included studies. These categories are often problematic as they erroneously group these distinct concepts together and centre on North American academic research norms. While this approach is widely applied in medical research, it often confounds race and ethnicity, which may impact the ability to analyse and discuss the content in a more robust way.

Racism has profound and pervasive effects on many aspects of a person’s health. However, the examination of racism alone does not give a complete picture of a nuanced social experience. Other factors related to one’s identity also contribute to health inequities for racialized and ethnically minoritized individuals. These components are often captured in social determinants of health and intersectionality frameworks and include categories such as sexism, access to education, discrimination related to social class, gender identity, etc [223]. Other important related factors may have been missed by limiting the analysis to racism.

Finally, when examining if authors discussed systemic individual provider factors in the interpretation of their findings, there was no pre-existing list of keywords. Although we created our own list of terms based on existing recommendations and guidelines, this may have resulted in a list that is too specific or too sensitive. For example, if the keyword list we created was too sensitive, it may have included some instances where racism was not necessarily directly named, resulting in an overcounting of the articles categorized as directly naming racism.

Recommendations

Based on our findings, we propose three groups of recommendations for palliative care researchers:

-

1.

Researcher education

Prior to beginning studies exploring race, ethnicity or racism, researchers should educate themselves about these topics and how they work as underlying mechanisms of health disparities. Evidence informed guides based on consultations from affected communities are available with concrete, detailed advice on how to approach and frame questions of enquiry [223].

-

2.

Research planning

Researchers must design their research questions with intention, grounded in evidence-based understandings of underlying mechanisms, such as systemic racism. They must also ensure that the data sets are collected and constructed to meaningfully meet the research objectives. If partitioning based on race or ethnicity is required for data analysis, it is important to avoid unnecessary groupings that may obscure findings for certain individual groups. If comparisons are warranted, researchers should avoid using White as the normative comparator. Rather, consider the reason and justification for comparison, avoiding automatic comparison to the perceived dominant group. Some alternate approaches include comparisons to the group’s historical data or to the population average [223]. Additionally, researchers should make sure that race and ethnicity are not conflated. If they are used together, this should be justified based on the researchers’ context or available data sets.

-

3.

Interpretation of findings

An evidence-based understanding of underlying root causes of health disparities, including the role of racism and its manifestations, should be used to guide the interpretation of findings. Differences should not be attributed to patient factors without evidence, as this may reflect researchers’ underlying biases and risks perpetuating stereotypes, and worsening disparities [15, 217].

Conclusion

Although the volume of palliative care literature examining the impacts of race or ethnicity on palliative care outcomes and experiences is increasing, there remains significant room for improvement when it comes to recognizing the role of systemic factors including racism when interpreting findings. Our study found that only a small proportion of researchers who deliberately set out to explore race or ethnicity explicitly named racism as a possible root cause. Researchers hold significant influence over the trajectory of health disparities research through the manner in which they frame, conduct, and interpret their studies. Failing to name evidence-based root causes such as systemic and interpersonal racism — because of lack of knowledge, fear, censoring, or just not considering it — threatens the effectiveness of future studies or interventions to address health disparities. Further, omitting the concept of racism when exploring racial and ethnic disparities may do harm by further reinforcing systems of oppression that affect racialized patients in need of palliative care.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Marcewicz L, Kunihiro SK, Curseen KA, Johnson K, Kavalieratos D. Application of critical race theory in palliative care research: a scoping review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(6):e667-684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.02.018.

Estrada LV, Agarwal M, Stone PW. Racial/ethnic disparities in nursing home end-of-life care: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(2):279-e901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.12.005.

Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(11):1329–34. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.9468.

Gott M, Wiles J, Mason K, Moeke-Maxwell T. Creating ‘safe spaces’: a qualitative study to explore enablers and barriers to culturally safe end-of-life care. Palliat Med. 2023;37(4):520–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163221138621.

Kim H, Anhang Price R, Bunker JN, Bradley M, Schlang D, Bandini JI, et al. Racial differences in end-of-life care quality between Asian Americans and non-Hispanic Whites in San Francisco bay area. J Palliat Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0627.

House of Commons, Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs. The challenges of delivering continuing care in first nation communities: report of the standing committee on indigenous and northern affairs. Canada: Ontario; 2018.

Gerlach LB, Kales HC, Kim HM, Zhang L, Strominger J, Covinsky K, et al. Prevalence of psychotropic and opioid prescribing among hospice beneficiaries in the United States, 2014–2016. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(6):1479–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17085.

Shin SH, Hui D, Chisholm G, Kang JH, Allo J, Williams J, et al. Frequency and outcome of neuroleptic rotation in the management of delirium in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;47(3):399–405. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2013.229.

Cea ME, Reid MC, Inturrisi C, Witkin LR, Prigerson HG, Bao Y. Pain assessment, management, and control among patients 65 years or older receiving hospice care in the U.S. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(5):663–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.05.020.

Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Johnson KS, Curtis LH, Setoguchi S. Racial differences in hospice use and patterns of care after enrollment in hospice among medicare beneficiaries with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2012;163(6):987 http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=cctr&NEWS=N&AN=CN-00968975.

Wang S-Y, Hsu SH, Aldridge MD, Cherlin E, Bradley E. Racial differences in health care transitions and hospice use at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(6):619–27. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2018.0436.

Russell D, Diamond EL, Lauder B, Dignam RR, Dowding DW, Peng TR, et al. Frequency and risk factors for live discharge from hospice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(8):1726–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14859.

Rosa WE, Gray TF, Chambers B, Sinclair S, Knaul FM, Bhadelia A, et al. Palliative care in the face of racism: a call to transform clinical practice, research, policy, and leadership. Health Aff Forefr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1377/forefront.20220207.574426.

World Health Organization. Strengthening primary health care to tackle racial discrimination, promote intercultural services and reduce health inequities research brief [Online research brief]. 2022. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/363854/9789240057104-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

Quest TE, Periyakoil VS, Quill TE, Casarett D. Racial equity in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(3):435–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.12.005.

Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley-Matoka M, Fine MJ. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2113–21. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628.

Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities 2020. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200630.939347/.

Roediger DR. Historical foundations of race National Museum of African American History and Culture: Smithsonian. Available from: https://nmaahc.si.edu/learn/talking-about-race/topics/historical-foundations-race.

Rosenberg NA, Pritchard JK, Weber JL, Cann HM, Kidd KK, Zhivotovsky LA, et al. Genetic structure of human populations. Science. 2002;298(5602):2381–5. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1078311.

Umaretiya PJ, Wolfe J, Bona K. Naming the problem: a structural racism framework to examine disparities in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(5):e461-463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.07.035.

Mbatha S. Understanding skin colour: exploring colourism and its articulation among Black and coloured students. Cape Town: University of Cape Town; 2016.

Sealy-Harrington J, Watson Hamilton J. Colour as a discrete ground of discrmination. Can J Human Rights. 2018;7(1). https://cjhr.ca/colour-as-a-discrete-ground-of-discrimination/.

Wang YJ, Chen XP, Chen WJ, Zhang ZL, Zhou YP, Jia Z. Ethnicity and health inequalities: an empirical study based on the 2010 China Survey of Social Change (cssc) in western China. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):637. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08579-8.

Braveman PA, Arkin E, Proctor D, Kauh T, Holm N. Systemic and structural racism: definitions, examples, health damages, and approaches to dismantling. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(2):171–8. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01394.

Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–5. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212.

American Medical Association. Organizational strategic plan to embed racial justice and advance health equity. [Online report]. 2021. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2021-05/ama-equity-strategic-plan.pdf.

National Human Genome Research Institute. Race [Web page]. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health; 2024. Available from: https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Race.

Office for National Statitisics. Ethnic group, national identity and religion [Web page]. Office for National Statistics (UK); 2021. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/classificationsandstandards/measuringequality/ethnicgroupnationalidentityandreligion.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. Prisma extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050.

Gottlieb M, Haas MRC, Daniel M, Chan TM. The scoping review: a flexible, inclusive, and iterative approach to knowledge synthesis. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5(3):e10609. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10609.

Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Jimenez R, Nilsson M, Paulk E, Stieglitz H, et al. Predictors of intensive end-of-life and hospice care in Latino and White advanced cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(10):1249–54. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0164.

Yang A, Goldin D, Nova J, Malhotra J, Cantor JC, Tsui J. Racial disparities in health care utilization at the end of life among New Jersey medicaid beneficiaries with advanced cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(6):e538-548. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.19.00767.

Wen Y, Jiang C, Koncicki HM, Horowitz CR, Cooper RS, Saha A, et al. Trends and racial disparities of palliative care use among hospitalized patients with ESKD on dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(9):1687–96. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2018121256.

Rice DR, Hyer JM, Diaz A, Pawlik TM. End-of-life hospice use and medicare expenditures among patients dying of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(9):5414–22. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-09606-7.

Lillemoe K, Lord A, Torres J, Ishida K, Czeisler B, Lewis A. Factors associated with DNR status after nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage. Neurohospitalist. 2020;10(3):168–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941874419873812.

Chuang E, Hope AA, Allyn K, Szalkiewicz E, Gary B, Gong MN. Gaps in provision of primary and specialty palliative care in the acute care setting by race and ethnicity. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(5):645-53.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.05.001.

Sharma RK, Dy SM. Documentation of information and care planning for patients with advanced cancer: associations with patient characteristics and utilization of hospital care. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2011;28(8):543–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909111404208.

Taylor JS, Zhang N, Rajan SS, Chavez-MacGregor M, Zhao H, Niu J, et al. How we use hospice: hospice enrollment patterns and costs in elderly ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;152(3):452–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.10.041.

Colon M. The experience of physicians who refer Latinos to hospice. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2012;29(4):254–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909111418777.

Ernst E, Schroeder C, Glover AC, Vesel T. Exploratory study comparing end-of-life care intensity between Chinese American and white advanced cancer patients at an American tertiary medical center. Palliat Med Rep. 2021;2(1):54–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/pmr.2020.0064.

Subramaniam AV, Patlolla SH, Cheungpasitporn W, Sundaragiri PR, Miller PE, Barsness GW, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in management and outcomes of cardiac arrest complicating acute myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(11):e019907. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.120.019907.

Miesfeldt S, Murray K, Lucas L, Chang CH, Goodman D, Morden NE. Association of age, gender, and race with intensity of end-of-life care for medicare beneficiaries with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(5):548–54. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2011.0310.

Wang S-Y, Aldridge MD, Canavan M, Cherlin E, Bradley E. Continuous home care reduces hospice disenrollment and hospitalization after hospice enrollment. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(6):813–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.05.031.

Chen JJ, Rawal B, Krishnan MS, Hertan LM, Shi DD, Roldan CS, et al. Patterns of specialty palliative care utilization among patients receiving palliative radiation therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;62(2):242–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.12.018.

Rosenfeld EB, Chan JK, Gardner AB, Curry N, Delic L, Kapp DS. Disparities associated with inpatient palliative care utilization by patients with metastatic gynecologic cancers: a study of 3337 women. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018;35(4):697–703. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909117736750.

Cruz-Flores S, Rodriguez GJ, Chaudhry MRA, Qureshi IA, Qureshi MA, Piriyawat P, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in hospital utilization in intracerebral hemorrhage. Int J Stroke. 2019;14(7):686–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493019835335.

Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Payne R, Tulsky JA. Race and residence: intercounty variation in Black-White differences in hospice use. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(5):681–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.12.006.

Rhodes RL, Xuan L, Halm EA. African American bereaved family members’ perceptions of hospice quality: do hospices with high proportions of African Americans do better? J Palliat Med. 2012;15(10):1137–41. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2012.0151.

Ache KA, Shannon RP, Heckman MG, Diehl NN, Willis FB. A preliminary study comparing attitudes toward hospice referral between African American and White American primary care physicians. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(5):542–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2010.0426.

Prince H, Nadin S, Crow M, Maki L, Monture L, Smith J, et al. If you understand you cope better with it: the role of education in building palliative care capacity in four first nations communities in Canada. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):768. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6983-y.

Slater T, Matheson A, Ellison-Loschmann L, Davies C, Earp R, Gellatly K, et al. Exploring Maori cancer patients’, their families’, community and hospice views of hospice care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2015;21(9):439–45. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.9.439.

Rhodes RL, Xuan L, Paulk ME, Stieglitz H, Halm EA. An examination of end-of-life care in a safety net hospital system: a decade in review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(4):1666–75. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2013.0179.

Hardy D, Chan W, Liu CC, Cormier JN, Xia R, Bruera E, et al. Racial disparities in length of stay in hospice care by tumor stage in a large elderly cohort with non-small cell lung cancer. Palliat Med. 2012;26(1):61–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216311407693.

Kirkendall A, Holland JM, Keene JR, Luna N. Evaluation of hospice care by family members of Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2015;32(3):313–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909114526969.

Karanth S, Rajan SS, Sharma G, Yamal JM, Morgan RO. Racial-ethnic disparities in end-of-life care quality among lung cancer patients: a SEER-medicare-based study. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(8):1083–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2018.04.014.

Hughes MC, Vernon E. We are here to assist all individuals who need hospice services: Hospices’ perspectives on improving access and inclusion for racial/ethnic minorities. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333721420920414.

Colon M, Lyke J. Comparison of hospice use by European Americans, African Americans, and Latinos: a follow-up study. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2015;32(2):205–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909113511143.

Beltran SJ. Hispanic hospice patients’ experiences of end-stage restlessness. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2018;14(1):93–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/15524256.2018.1437589.

Bell CL, Kuriya M, Fischberg D. Hospice referrals and code status: outcomes of inpatient palliative care consultations among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(4):557–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.01.010.

Khan MZ, Zahid S, Kichloo A, Jamal S, Minhas AMK, Khan MU, et al. Gender, racial, ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in palliative care encounters in ischemic strokes admissions. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2022;35:147–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carrev.2021.04.004.

Karikari-Martin P, McCann JJ, Farran CJ, Hebert LE, Haffer SC, Phillips M. Race, any cancer, income, or cognitive function: what influences hospice or aggressive services use at the end of life among community-dwelling medicare beneficiaries? Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2016;33(6):537–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909115574263.

Dillon PJ, Basu A. African Americans and hospice care: a culture-centered exploration of enrollment disparities. J Health Commun. 2016;31(11):1385–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2015.1072886.

Rubens M, Ramamoorthy V, Saxena A, Das S, Appunni S, Rana S, et al. Palliative care consultation trends among hospitalized patients with advanced cancer in the United States, 2005 to 2014. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2019;36(4):294–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909118809975.

Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Goldstein R. Ethnic differences in hospice enrollment following inpatient palliative care consultation. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):598–600. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2078.

Faigle R, Ziai WC, Urrutia VC, Cooper LA, Gottesman RF. Racial differences in palliative care use after stroke in majority-white, minority-serving, and racially integrated U.S. hospitals. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(12):2046–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002762.

Kathpalia P, Smith A, Lai JC. Underutilization of palliative care services in the liver transplant population. World J Transplant. 2016;6(3):594–8. https://doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v6.i3.594.

Paredes AZ, Hyer JM, Palmer E, Lustberg MB, Pawlik TM. Racial/ethnic disparities in hospice utilization among medicare beneficiaries dying from pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25(1):155–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-020-04568-9.

Laguna J, Goldstein R, Braun W, Enguidanos S. Racial and ethnic variation in pain following inpatient palliative care consultations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(3):546–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12709.

Maddalena V, Bernard WT, Davis-Murdoch S, Smith D. Awareness of palliative care and end-of-life options among African Canadians in Nova Scotia. J Transcult Nurs. 2013;24(2):144–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659612472190.

Haines KL, Jung HS, Zens T, Turner S, Warner-Hillard C, Agarwal S. Barriers to hospice care in trauma patients: the disparities in end-of-life care. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018;35(8):1081–4. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909117753377.

Dembinsky M. Exploring Yamatji perceptions and use of palliative care: an ethnographic study. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2014;20(8):387–93. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.8.387.

Woods JA, Johnson CE, Ngo HT, Katzenellenbogen JM, Murray K, Thompson SC. Symptom-related distress among indigenous Australians in specialist end-of-life care: findings from the multi-jurisdictional palliative care outcomes collaboration data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9):3131.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093131.

Shiovitz S, Bansal A, Burnett-Hartman AN, Karnopp A, Adams SV, Warren-Mears V, et al. Cancer-directed therapy and hospice care for metastatic cancer in American Indians and Alaska natives. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(7):1138–43.https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0251.

Neiman T. Nurses’ perceptions of basic palliative care in the Hmong population. J Transcult Nurs. 2019;30(6):576–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659619828054.

Reyes-Gibby CC, Anderson KO, Shete S, Bruera E, Yennurajalingam S. Early referral to supportive care specialists for symptom burden in lung cancer patients: a comparison of non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic Blacks. Cancer. 2012;118(3):856–63.https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26312.

Woods JA, Katzenellenbogen JM, Murray K, Johnson CE, Thompson SC. Occurrence and timely management of problems requiring prompt intervention among indigenous compared with non-indigenous Australian palliative care patients: a multijurisdictional cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e042268.https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26312.

Austin AM, Carmichael DQ, Bynum JPW, Skinner JS. Measuring racial segregation in health system networks using the dissimilarity index. Soc Sci Med. 2019;240:112570.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112570.

Teno JM, Plotzke M, Christian T, Gozalo P. Examining variation in hospice visits by professional staff in the last 2 days of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(3):364–70.https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7479.

Rhodes RL, Batchelor K, Lee SC, Halm EA. Barriers to end-of-life care for African Americans from the providers’ perspective: opportunity for intervention development. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2015;32(2):137–43.https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909113507127.

Price RA, Parast L, Haas A, Teno JM, Elliott MN. Black and Hispanic patients receive hospice care similar to that of white patients when in the same hospices. Health Aff. 2017;36(7):1283–90.https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0151.

Nadimi F, Currow DC. As death approaches: a retrospective survey of the care of adults dying in Alice Springs hospital. Aust J Rural Health. 2011;19(1):4–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2010.01169.x.

Ornstein KA, Roth DL, Huang J, Levitan EB, Rhodes JD, Fabius CD, et al. Evaluation of racial disparities in hospice use and end-of-life treatment intensity in the regards cohort. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2014639-e. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14639.

Thongprayoon C, Kaewput W, Petnak T, O'Corragain OA, Boonpheng B, Bathini T, et al. Impact of palliative care services on treatment and resource utilization for hepatorenal syndrome in the united states. Medicines (Basel). 2021;8(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/medicines8050021.

Dillon PJ, Roscoe LA. African Americans and hospice care: a narrative analysis. Narrat Inq Bioeth. 2015;5(2):151–65. https://doi.org/10.1353/nib.2015.0049.

Taylor JS, Rajan SS, Zhang N, Meyer LA, Ramondetta LM, Bodurka DC, et al. End-of-life racial and ethnic disparities among patients with ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(16):1829–35. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.70.2894.

Sharma RK, Cameron KA, Chmiel JS, Von Roenn JH, Szmuilowicz E, Prigerson HG, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in inpatient palliative care consultation for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3802–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6458.

Campbell CL, Baernholdt M, Yan G, Hinton ID, Lewis E. Racial/ethnic perspectives on the quality of hospice care. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2013;30(4):347–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909112457455.

Samuel-Ryals CA, Mbah OM, Hinton SP, Cross SH, Reeve BB, Dusetzina SB. Evaluating the contribution of patient-provider communication and cancer diagnosis to racial disparities in end-of-life care among medicare beneficiaries. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(11):3311–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06778-6.

Patel B, Secheresiu P, Shah M, Racharla L, Alsalem AB, Agarwal M, et al. Trends and predictors of palliative care referrals in patients with acute heart failure. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2019;36(2):147–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909118796195.

Johnson T, Walton S, Levine S, Fister E, Baron A, O’Mahony S. Racial and ethnic disparity in palliative care and hospice use. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(2):e36-40. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.42399.

Zheng NT, Mukamel DB, Caprio T, Cai S, Temkin-Greener H. Racial disparities in in-hospital death and hospice use among nursing home residents at the end of life. Med Care. 2011;49(11):992–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318236384e.

Dosani N, Bhargava R, Arya A, Pang C, Tut P, Sharma A, et al. Perceptions of palliative care in a South Asian community: findings from an observational study. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00646-6.

Zullig LL, Carpenter WR, Provenzale DT, Weinberger M, Reeve BB, Williams CD, et al. The association of race with timeliness of care and survival among veterans affairs health care system patients with late-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Manage Res. 2013;5:157–63. https://doi.org/10.2147/cmar.s46688.

Thomas BA, Rodriguez RA, Boyko EJ, Robinson-Cohen C, Fitzpatrick AL, O’Hare AM. Geographic variation in Black-White differences in end-of-life care for patients with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(7):1171–8. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.06780712.

Chung D, Sue A, Hughes S, Simmons J, Hailu T, Swift C, et al. Impact of race/ethnicity on pain management outcomes in a community-based teaching hospital following inpatient palliative care consultation. Cureus. 2016;8(10):e823.https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.823.

Dillon PJ, Basu A. Toward eliminating hospice enrollment disparities among African Americans: a qualitative study. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(1):219–37.https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2016.0014.

Marr L, Neale D, Wolfe V, Kitzes J. Confronting myths: the native American experience in an academic inpatient palliative care consultation program. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(1):71–6.https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2011.0197.

Frahm KA, Brown LM, Hyer K. Racial disparities in end-of-life planning and services for deceased nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(9):e8197-8111.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2012.07.021.

Johnson LA, Blew A, Schreier AM. Health disparities in hospice utilization and length of stay in a diverse population with lung cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2019;36(6):513–8.https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909118823721.

Cole AP, Nguyen DD, Meirkhanov A, Golshan M, Melnitchouk N, Lipsitz SR, et al. Association of care at minority-serving vs non–minority-serving hospitals with use of palliative care among racial/ethnic minorities with metastatic cancer in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(2):e187633-e. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7633.

Reese DJ, Smith MR, Butler C, Shrestha S, Erwin DO. African American client satisfaction with hospice: a comparison of primary caregiver experiences within and outside of hospice. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2014;31(5):495–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909113494462.

Rizzuto J, Aldridge MD. Racial disparities in hospice outcomes: a race or hospice-level effect? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(2):407–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15228.

Sharma RK, Freedman VA, Mor V, Kasper JD, Gozalo P, Teno JM. Association of racial differences with end-of-life care quality in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1858–60. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4793.

Fairfield KM, Murray KM, Wierman HR, Han PKJ, Hallen S, Miesfeldt S, et al. Disparities in hospice care among older women dying with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125(1):14–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.041.

Isaacson M, Karel B, Varilek BM, Steenstra WJ, Tanis-Heyenga JP, Wagner A. Insights from health care professionals regarding palliative care options on South Dakota reservations. J Transcult Nurs. 2015;26(5):473–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659614527623.

Jones RC, Creutzfeldt CJ, Cox CE, Haines KL, Hough CL, Vavilala MS, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in health care utilization following severe acute brain injury in the United States. J Intensive Care Med. 2020;36(11):1258–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885066620945911.

Guadagnolo BA, Huo J, Buchholz TA, Petereit DG. Disparities in hospice utilization among American Indian medicare beneficiaries dying of cancer. Ethn Dis. 2014;24(4):393–8 http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med11&NEWS=N&AN=25417419.

Worster B, Bell DK, Roy V, Cunningham A, LaNoue M, Parks S. Race as a predictor of palliative care referral time, hospice utilization, and hospital length of stay: a retrospective noncomparative analysis. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018;35(1):110–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909116686733.

Nguyen MT, Feeney T, Kim C, Drake FT, Mitchell SE, Bednarczyk M, et al. Patient-level factors influencing palliative care consultation at a safety-net urban hospital. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2020;38(11):1299–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909120981764.

Hardy D, Chan W, Liu CC, Cormier JN, Xia R, Bruera E, et al. Racial disparities in the use of hospice services according to geographic residence and socioeconomic status in an elderly cohort with nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(7):1506–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25669.

Kirkendall A, Shen JJ, Gan Y. Associations of race and other socioeconomic factors with post-hospitalization hospice care settings. Ethn Dis. 2014;24(2):236–42 http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med11&NEWS=N&AN=24804373.

Di Luca DG, Feldman M, Jimsheleishvili S, Margolesky J, Cordeiro JG, Diaz A, et al. Trends of inpatient palliative care use among hospitalized patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020;77:13–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.06.011.

Salomon S, Chuang E, Bhupali D, Labovitz D. Race/ethnicity as a predictor for location of death in patients with acute neurovascular events. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018;35(1):100–3. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909116687258.

Bajwah S, Edmonds P, Yorganci E, Chester R, Russell K, Lovell N, et al. The association between ethnicity, socioeconomic deprivation and receipt of hospital-based palliative care for people with covid-19: a dual centre service evaluation. Palliat Med. 2021;35(8):1514–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163211022959.

Check DK, Samuel CA, Rosenstein DL, Dusetzina SB. Investigation of racial disparities in early supportive medication use and end-of-life care among medicare beneficiaries with stage IV breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(19):2265–70. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8162.

Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Earle CC, LaCasce AS, Abel GA. Hospice use among patients with lymphoma: impact of disease aggressiveness and curability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(1):djv280.https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv280.

Noh H, Schroepfer TA. Terminally ill African American elders’ access to and use of hospice care. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2015;32(3):286–97.https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909113518092.

Russell D, Luth EA, Ryvicker M, Bowles KH, Prigerson HG. Live discharge from hospice due to acute hospitalization: the role of neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics and race/ethnicity. Med Care. 2020;58(4):320–8.https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001278.

Abbas A, Madison Hyer J, Pawlik TM. Race/ethnicity and county-level social vulnerability impact hospice utilization among patients undergoing cancer surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(4):1918–26. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-09227-6.

Russell D, Baik D, Jordan L, Dooley F, Hummel SL, Prigerson HG, et al. Factors associated with live discharge of heart failure patients from hospice: a multimethod study. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7(7):550–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2019.01.010.

Chidiac C, Feuer D, Flatley M, Rodgerson A, Grayson K, Preston N. The need for early referral to palliative care especially for Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups in a covid-19 pandemic: findings from a service evaluation. Palliat Med. 2020;34(9):1241–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320946688.

Kutney-Lee A, Smith D, Thorpe J, Del Rosario C, Ibrahim S, Ersek M. Race/ethnicity and end-of-life care among veterans. Med Care. 2017;55(4):342–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000637.

Chatterjee K, Harrington S, Sexton K, Goyal A, Robertson RD, Corwin HL. Impact of palliative care utilization for surgical patients receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation: national trends (2009–2013). Joint Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2020;46(9):493–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjq.2020.03.011.

Chong K, Silver SA, Long J, Zheng Y, Pankratz VS, Unruh ML, et al. Infrequent provision of palliative care to patients with dialysis-requiring AKI. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(11):1744–52. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.00270117.

Singh T, Peters SR, Tirschwell DL, Creutzfeldt CJ. Palliative care for hospitalized patients with stroke: results from the 2010 to 2012 national inpatient sample. Stroke. 2017;48(9):2534–40. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016893.

Burgio KL, Williams BR, Dionne-Odom JN, Redden DT, Noh H, Goode PS, et al. Racial differences in processes of care at end of life in VA medical centers: planned secondary analysis of data from the beacon trial. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(2):157–63. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0311.

Lepore MJ, Miller SC, Gozalo P. Hospice use among urban Black and White U.S. nursing home decedents in 2006. Gerontologist. 2011;51(2):251–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnq093.

Du XL, Parikh RC, Lairson DR. Racial and geographic disparities in the patterns of care and costs at the end of life for patients with lung cancer in 2007–2010 after the 2006 introduction of bevacizumab. Lung Cancer. 2015;90(3):442–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.09.017.

Mullins MA, Ruterbusch JJ, Clarke P, Uppal S, Wallner LP, Cote ML. Trends and racial disparities in aggressive end-of-life care for a national sample of women with ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2021;127(13):2229–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33488.

Thienprayoon R, Lee SC, Leonard D, Winick N. Racial and ethnic differences in hospice enrollment among children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(10):1662–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24590.

Frey R, Gott M, Raphael D, Black S, Teleo-Hope L, Lee H, et al. Where do I go from here’? A cultural perspective on challenges to the use of hospice services. Health Soc Care Community. 2013;21(5):519–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12038.

D’Angelo D, Di Nitto M, Giannarelli D, Croci I, Latina R, Marchetti A, et al. Inequity in palliative care service full utilisation among patients with advanced cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2020;59(6):620–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2020.1736335.

Nayar P, Qiu F, Watanabe-Galloway S, Boilesen E, Wang H, Lander L, et al. Disparities in end of life care for elderly lung cancer patients. J Community Health. 2014;39(5):1012–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-014-9850-x.

Fiala MA, Gettinger T, Wallace CL, Vij R, Wildes TM. Cost differential associated with hospice use among older patients with multiple myeloma. J Geriatric Oncol. 2020;11(1):88–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.06.010.

Lee K, Gani F, Canner JK, Johnston FM. Racial disparities in utilization of palliative care among patients admitted with advanced solid organ malignancies. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2021;38(6):539–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909120922779.

Anand V, Vallabhajosyula S, Cheungpasitporn W, Frantz RP, Cajigas HR, Strand JJ, et al. Inpatient palliative care use in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: temporal trends, predictors, and outcomes. Chest. 2020;158(6):2568–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.079.

Khan MZ, Khan MU, Munir MB. Trends and disparities in palliative care encounters in acute heart failure admissions; insight from national inpatient sample. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021;23:52–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carrev.2020.08.024.

Nuñez A, Holland JM, Beckman L, Kirkendall A, Luna N. A qualitative study of the emotional and spiritual needs of hispanic families in hospice. Palliat Support Care. 2017:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1478951517000190.

Jarosek SL, Shippee TP, Virnig BA. Place of death of individuals with terminal cancer: new insights from medicare hospice place-of-service codes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(9):1815–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14269.

Cote-Arsenault D, Denney-Koelsch EM, McCoy TP, Kavanaugh K. African American and Latino bereaved parent health outcomes after receiving perinatal palliative care: a comparative mixed methods case study. Appl Nurs Res. 2019;50:151200.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2019.151200.

Watanabe-Galloway S, Zhang W, Watkins K, Islam KM, Nayar P, Boilesen E, et al. Quality of end-of-life care among rural medicare beneficiaries with colorectal cancer. J Rural Health. 2014;30(4):397–405.https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12074.

Xian Y, Holloway RG, Smith EE, Schwamm LH, Reeves MJ, Bhatt DL, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in process of care and outcomes among patients hospitalized with intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2014;45(11):3243–50. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.114.005620.

Shanmugasundaram S. Unmet needs of the Indian family members of terminally ill patients receiving palliative care services. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2015;17(6):536–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/njh.0000000000000195.

Sammon JD, McKay RR, Kim SP, Sood A, Sukumar S, Hayn MH, et al. Burden of hospital admissions and utilization of hospice care in metastatic prostate cancer patients. Urology. 2015;85(2):343–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2014.09.053.

Fosler L, Staffileno BA, Fogg L, O’Mahony S. Cultural differences in discussion of do-not-resuscitate status and hospice. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2015;17(2):128–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/njh.0000000000000135.

Allsop MJ, Ziegler LE, Mulvey MR, Russell S, Taylor R, Bennett MI. Duration and determinants of hospice-based specialist palliative care: a national retrospective cohort study. J Palliat Med. 2018;32(8):1322–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216318781417.

Shahid S, Bessarab D, van Schaik KD, Aoun SM, Thompson SC. Improving palliative care outcomes for Aboriginal Australians: service providers’ perspectives. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12(1):26.https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684x-12-26.

Saito AM, Landrum MB, Neville BA, Ayanian JZ, Weeks JC, Earle CC. Hospice care and survival among elderly patients with lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(8):929–39.https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2010.0522.

Tramontano AC, Nipp R, Kong CY, Yerramilli D, Gainor JF, Hur C. Hospice use and end-of-life care among older patients with esophageal cancer. Health Sci Rep. 2018;1(9):e76. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.76.

Temkin-Greener H, Wenhan G, Yechu H, Yue L, Caprio T, Schwartz L, et al. End-of-life care in assisted living communities: race and ethnicity, dual enrollment status, and state regulations. Health Aff. 2022;41(5):654–62. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01677.

Kawai F, Pan CX, Zaravinos J, Maw MM, Lee G. Do Hispanics prefer to be full code at the end of life? The impact of palliative care consults on clarifying code status preferences and hospice referrals in Spanish-speaking patients. Palliat Support Care. 2021;19(2):193–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951520000425.

Soltoff A, Purvis S, Ravicz M, Isaacson MJ, Duran T, Johnson G, et al. Factors influencing palliative care access and delivery for great plains American Indians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;64(3):276–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.05.011.

Starr LT, Ulrich CM, Perez GA, Aryal S, Junker P, O’Connor NR, et al. Hospice enrollment, future hospitalization, and future costs among racially and ethnically diverse patients who received palliative care consultation. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2022;39(6):619–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/10499091211034383.

Nwogu-Onyemkpa E, Dongarwar D, Salihu HM, Akpati L, Marroquin M, Abadom M, et al. Inpatient palliative care use by patients with sickle cell disease: a retrospective cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(8):e057361.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057361.

Price M, Howell EP, Dalton T, Ramirez L, Howell C, Williamson T, et al. Inpatient palliative care utilization for patients with brain metastases. Neurooncol Pract. 2021;8(4):441–50.https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npab016.

McKee MN, Palama BK, Hall M, LaBelle JL, Bohr NL, Hoehn KS. Racial and ethnic differences in inpatient palliative care for pediatric stem cell transplant patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2022;23(6):417–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000002916.

Beltran SJ. Latino families’ decisions to accept hospice care. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2022;39(2):152–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/10499091211042336.

Goertz A, Dejoy R, Torres R, Lo K, Azmaiparashvili Z, Patarroyo-Aponte, et al. Palliative care consultation and cost of stay in out of hospital cardiac arrest. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2022;39(11):1333–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/10499091221078978.

Williamson TL, Adil SM, Shalita C, Charalambous LT, Mitchell T, Yang Z, et al. Palliative care consultations in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: who receives palliative care consultations and what does that mean for utilization? Neurocrit Care. 2022;36(3):781–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-021-01366-2.

Funnell S, Walker J, Letendre A, Bearskin RLB, Manuel D, Scott M, et al. Places of death and places of care for indigenous peoples in Ontario: a retrospective cohort study. Can J Public Health. 2021;112(4):685–96. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-021-00482-y.

DeGroote NP, Allen KE, Falk EE, Velozzi-Averhoff C, Wasilewski-Masker K, Johnson K, et al. Relationship of race and ethnicity on access, timing, and disparities in pediatric palliative care for children with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(1):923–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06500-6.

Umaretiya PJ, Li A, McGovern A, Ma C, Wolfe J, Bona K. Race, ethnicity, and goal-concordance of end-of-life palliative care in pediatric oncology. Cancer. 2021;127(20):3893–900. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33768.

Lin PJ, Zhu Y, Olchanski N, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ, Faul JD, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in hospice use and hospitalizations at end-of-life among medicare beneficiaries with dementia. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2216260-e. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.16260.

Zametkin E, Williams E, Feingold-Link M, Jiang L, Martin E, Erqou S, et al. Racial differences in burdensome transitions in heart failure patients with palliative care: a propensity-matched analysis. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(7):1122–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2021.0317.

Bajwah S, Koffman J, Hussain J, Bradshaw A, Hocaoglu MB, Fraser LK, et al. Specialist palliative care services response to ethnic minority groups with covid-19: equal but inequitable-an observational study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003083.

Bandini JI, Schulson LB, Setodji CM, Williams J, Ast K, Ahluwalia SC. “Palliative care is the only medical field that i feel like I’m treated as a person, not as a Black person”: a mixed-methods study of minoritized patient experiences with palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2022;26(2):220–7.https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2022.0237.

Isenberg SR, Bonares M, Kurahashi AM, Algu K, Mahtani R. Race and birth country are associated with discharge location from hospital: a retrospective cohort study of demographic differences for patients receiving inpatient palliative care. eClinicalMedicine. 2022;45:101303.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101303.

Hunt LJ, Gan S, Boscardin WJ, Yaffe K, Ritchie CS, Aldridge MD, et al. A national study of disenrollment from hospice among people with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(10):2858–70.https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17912.

Tobin RS, Samsky MD, Kuchibhatla M, O’Connor CM, Fiuzat M, Warraich HJ, et al. Race differences in quality of life following a palliative care intervention in patients with advanced heart failure: insights from the palliative care in heart failure trial. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(2):296–300. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2021.0220.

Kiker WA, Cheng S, Pollack LR, Creutzfeldt CJ, Kross EK, Curtis JR, et al. Admission code status and end-of-life care for hospitalized patients with covid-19. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;64(4):359–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.06.014.

Mahilall R, Swartz L. I am dying a slow death of white guilt’: spiritual carers in a South African hospice navigate issues of race and cultural diversity. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2021;46:779–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-021-09750-5.

Shepard V, Al Snih S, Burke R, Downer B, Kuo YF, Malagaris I, et al. Characteristics associated with Mexican-American hospice use: retrospective cohort study using the hispanic established population for the epidemiologic study of the elderly (h-epese). Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2022;10499091221110125. https://doi.org/10.1177/10499091221110125.

Turkman YE, Williams CP, Jackson BE, Dionne-Odom JN, Taylor R, Ejem D, et al. Disparities in hospice utilization for older cancer patients living in the Deep South. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(1):86–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.04.006.

Cicolello K, Anandarajah G. Multiple stakeholders’ perspectives regarding barriers to hospice enrollment in diverse patient populations: a qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(5):869–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.02.012.

Smith LN, Rhodes RL, Xuan L, Halm EA. Predictors of placement of inpatient palliative care consult orders among patients with breast, lung, and colon cancer in a safety net hospital system. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018;35(4):586–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909117733473.

Noh H, Bui C, Mack JW. Factors affecting hospice use among adolescents and young adult cancer patients. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2021.0225.

Estrada LV, Harrison JM, Dick AW, Luchsinger JA, Dhingra L, Stone PW. Examining regional differences in nursing home palliative care for Black and Hispanic residents. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(8):1228–35. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2021.0416.

Giap F, Ma SJ, Oladeru OT, Hong Y-R, Yu B, Mailhot Vega RB, et al. Palliative care utilization and racial and ethnic disparities among women with de novo metastatic breast cancer in the United States. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2023;200(3):347–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-023-06963-7.

Soipe AI, Leggat JE, Abioye AI, Devkota K, Oke F, Bhuta K, et al. Current trends in hospice care usage for dialysis patients in the USA. J Nephrol. 2023;36(7):2081–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-023-01721-w.

Khayal IS, O’Malley AJ, Barnato AE. Clinically informed machine learning elucidates the shape of hospice racial disparities within hospitals. NPJ Digit Med. 2023;6(1):190. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-023-00925-5.

Fisher MC, Chen X, Crews DC, DeGroot L, Eneanya ND, Ghildayal N, et al. Advance care planning and palliative care consultation in kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2023.07.018.

Ali H, Pamarthy R, Bolick NL, Leland W, Lee T. Inpatient outcomes and racial disparities of palliative care consults in mechanically ventilated patients in the United States. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2022;35(6):762–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2022.2106537.

Jin MC, Hsin G, Ratliff J, Thomas R, Zygourakis CC, Li G, et al. Modifiers of and disparities in palliative and supportive care timing and utilization among neurosurgical patients with malignant central nervous system tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(10):2567. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14102567.

Anderson E, Twiggs C, Goins RT, Astleford N, Winchester B. Nephrology and palliative care providers’ beliefs in engaging American Indian patients in palliative care conversations. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(12):1810–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2021.0612.

Hunt LJ, Gan S, Smith AK, Aldridge MD, Boscardin WJ, Harrison KL, et al. Hospice quality, race, and disenrollment in hospice enrollees with dementia. J Palliat Med. 2023;26(8):1100–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2023.0011.

Anandarajah G, Mennillo MR, Wang S, DeFries K, Gottlieb JL. Trust as a central factor in hospice enrollment disparities among ethnic and racial minority patients: a qualitative study of interrelated and compounding factors impacting trust. J Palliat Med. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2023.0090.

Siddiqui S, Bouhassira D, Kelly L, Hayes M, Herbst A, Ohnigian S, et al. Examining the role of race in end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a single-center observational study. Palliat Med Rep. 2023;4(1):264–73. https://doi.org/10.1089/pmr.2023.0037.

Peeler A, Davidson PM, Gleason KT, Stephens RS, Ferrell B, Kim BS, et al. Palliative care utilization in patients requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: an observational study. ASAIO J. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1097/mat.0000000000002021.

Dewhurst F, Tomkow L, Poole M, McLellan E, Kunonga TP, Damisa E, et al. Unrepresented, unheard and discriminated against: a qualitative exploration of relatives’ and professionals’ views of palliative care experiences of people of African and Caribbean descent during the covid-19 pandemic. Palliat Med. 2023;37(9):1447–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163231188156.

Elkaryoni A, Darki A, Bunte M, Mamas MA, Weinberg I, Elgendy IY. Palliative care penetration among hospitalizations with acute pulmonary embolism: a nationwide analysis. J Palliat Care. 2022:8258597221078389. https://doi.org/10.1177/08258597221078389.

Aamodt WW, Bilker WB, Willis AW, Farrar JT. Sociodemographic and geographic disparities in end-of-life health care intensity among medicare beneficiaries with Parkinson disease. Neurol Clin Pract. 2023;13(4):e200171. https://doi.org/10.1212/cpj.0000000000200171.

Weerasinghe S. Inpatient end-of-life care delivery: discordance and concordance analysis of Canadian palliative care professionals’ and South Asian family caregivers’ perspectives. Palliat Care Soc Pract. 2023;17:26323524221145950. https://doi.org/10.1177/26323524221145953.

Fassas S, King D, Shay M, Shockett E, Yamane D, Hawkins K. Palliative medicine and end of life care between races in an academic intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2023:8850666231200383. https://doi.org/10.1177/08850666231200383.

Zapata C, Poore T, O'Riordan D, Pantilat SZ. Hispanic/latinx and spanish language concordance among palliative care clinicians and patients in hospital settings in california. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2023:10499091231171337. https://doi.org/10.1177/10499091231171337.

Tabuyo-Martin A, Torres-Morales A, Pitteloud MJ, Kshetry A, Oltmann C, Pearson JM, et al. Palliative medicine referral and end-of-life interventions among racial and ethnic minority patients with advanced or recurrent gynecologic cancer. Cancer Control. 2023;30:10732748231157192. https://doi.org/10.1177/10732748231157191.