Abstract

Background

This study anlyzed whether family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer suffer impaired sleep quality, increased strain, reduced quality of life or increased care burden due to the presence and heightened intensity of symptoms in the person being cared for.

Method

A total of 41 patient-caregiver dyads (41 caregivers and 41 patients with advanced cancer) were recruited at six primary care centres in this cross-sectional study. Data were obtained over a seven-month period. Caregiver’s quality of sleep (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index), caregiver’s quality of life (Quality of Life Family Version), caregiver strain (Caregiver Strain Index), patients’ symptoms and their intensity (Edmonton Symptom Assessment System), and sociodemographic, clinical and care-related data variables were assessed. The associations were determined using non-parametric Spearman correlation.

Results

Total Edmonton Symptom Assessment System was significantly related to overall score of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (r = 0.365, p = 0.028), the Caregiver Strain Index (r = 0.45, p = 0.005) and total Quality of Life Family Version (r = 0.432, p = 0.009), but not to the duration of daily care (r = -0.152, p = 0.377).

Conclusions

Family caregivers for patients with advanced cancer suffer negative consequences from the presence and intensity of these patients’ symptoms. Therefore, optimising the control of symptoms would benefit not only the patients but also their caregivers. Thus, interventions should be designed to improve the outcomes of patient-caregiver dyads in such cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Rising numbers of patients with advanced cancer are receiving home palliative care, due to the increased prevalence of this disease [1] and to the recognised benefits of early palliative care [2, 3] in terms of patient satisfaction and the alleviation of the changeable and frequently severe symptoms presented [4,5,6,7].

Given the characteristics and often worsening nature of their symptoms, many patients with advanced cancer require quality palliative health care in the home, which in most cases is provided by a family caregiver, in collaboration with the health system [8,9,10]. In home palliative care, these family caregivers are usually relatives of the patient, most commonly spouse, parent or son/daughter, although other family members or friends sometimes perform this role, for which no financial compensation is obtained [11, 12].

Caregivers of patients with advanced cancer can be affected both physically and psychologically [13] and be subjected to considerable demands on their time, physical energy and mental resources [14]. The most frequent disorders experienced by such caregivers involve their mental health, in areas such as depressed mood and anxiety [15, 16]. Others include fatigue [17, 18], impaired sleep [19, 20], caregiver overload and overall reduced quality of life [21,22,23,24].

These disorders are well documented; however, their relation with the patient’s condition has received less research attention, and the few studies that have investigated this question have reported widely varying conclusions [25,26,27]. Thus, the main aim of this study is to determine whether the presence and intensity of the symptoms of patients with advanced cancer have a negative impact on the family caregiver, in terms of sleep quality, strain, quality of life and care burden.

Methods

Eligibility criteria and sampling

For this descriptive cross-sectional study, the patient-caregiver dyads were recruited at six primary care centres in the Málaga-Guadalhorce Health District (Málaga, Spain).

The study sample was drawn from the lists of cancer patients recorded under the Palliative Care Assistance Process. The following inclusion criteria were applied for participation: (1) Cancer patients in home palliative care who have a family caregiver; (2) Both patient and caregiver are aged ≥ 18 years; (3) Both patient and caregiver give signed informed consent to participate. Excluded from the study were (1) Patients with advanced disease, whose life expectancy was only a few days; (2) Patients with advanced stage dementia or psychological disorders making them incapable of taking rational decisions. The selection of participants is detailed in Fig. 1.

Measures

The following study variables were considered:

Sociodemographic, clinical and care-related data

Caregivers: age, sex, marital status, education, paid employment, daily hours dedicated to care, relationship with the patient. These variables were indicated by the caregiver in a personal interview.

Patients in palliative care: age, sex, marital status, education, total time in palliative care and type of cancer. Total time of palliative care was estimated according to the date in which oncology referred the patient to palliative care, this data is available in the patient’s health record.

Caregiver’s quality of sleep

The caregiver’s quality of sleep was determined using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [28], which evaluates seven sleep domains: subjective quality, latency, duration, efficiency, sleep disorders, use of medications for sleep and daytime dysfunction during the past month. The sum of the scores obtained in each of the seven partial components generates a total score, ranging from 0–21. A total score > 5 indicates poor sleep quality.

Caregiver’s quality of life

The caregiver’s quality of life (QoL) was evaluated using the Quality of Life Family Version (FQOL) instrument [29], which is commonly used to assess the QoL of caregivers of patients with chronic disease. The FQOL consists of 35 items, scored from 1 to 4, assessing physical, psychological, spiritual and social aspects of QoL. The total score obtained ranges from 0 to 100, with 100 being the best possible QoL.

Caregiver strain

Caregiver strain was determined using the Caregiver Strain Index (CSI) questionnaire [30], which consists of 13 dichotomous (Yes–No) items. Each affirmative answer scores 1, and the total score obtained ranges from 0 to 13 points. A total score of ≥ 7 suggests a high level of strain.

Patients’ symptoms and their intensity

The patients’ symptoms and their intensity were measured using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) scale [31, 32]. This instrument evaluates the presence and intensity of the following symptoms, during a specific period: pain, fatigue, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, dyspnoea, appetite, reduced wellbeing and sleep alterations. The intensity of the symptoms is scored from 0 to 10, with 0 meaning absence of the symptom and 10 its greatest possible severity. The total score obtained ranges from 0 to100.

All mentioned questionnaires were applied in caregivers and patient in the validated Spanish version.

Data collection

The study sample consisted of 41 patients and the corresponding 41 caregivers, who were recruited during the period June-December 2020, according to the following procedure. After confirming that both the patient and his/her family caregiver met the inclusion criteria, they were fully informed about the study (both orally and in writing). If both parties agreed to participate, they were then asked to sign the informed consent form. Subsequently, the caregiver-patient dyads were interviewed in their home by a nurse collaborating with the study and asked to complete the questionnaires.

Statistical methods

The characteristics of the participants are presented as mean values (± standard deviation (SD)) for the quantitative variables, and as absolute frequencies (n) and percentages (%) for the categorical ones. The associations between total ESAS and ‘hours per day dedicated to care’, total PSQI, total FQOL and CSI were determined using non-parametric Spearman correlation. All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 22 software, and p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Sociodemographic, clinical and care-related characteristics of a) patients with advanced cancer; b) their caregivers

Initial contact was made with 94 potential participants. Of these, eight did not meet the inclusion criteria, four caregivers and two patients declined to participate, and six patients died before the interview could be held. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the caregivers, and Table 2, the corresponding data for the patients.

Descriptive data for the study variables

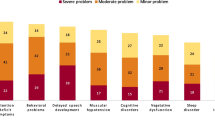

The overall mean PSQI for the caregivers was 7.66 (SD: 3.81). A poor quality of sleep (PSQI > 5) was reported by 31 caregivers, or 75.6% of the sample. The following mean FQOL scores were obtained for the caregivers: physical aspects 38.04 (SD: 19.73), psychological aspects 52.67 (SD: 11.08), spiritual aspects 65.73 (SD: 14.7), social aspects 39.74 (SD: 18.46), and total FQOL 52.75 (SD: 12.11). The mean CSI result was 6.8 (SD: 3.03). A score of ≥ 7, suggesting a high level of effort, was recorded for 23 caregivers (56.1%). Table 3 shows the patients’ symptom severity, according to the ESAS scores obtained.

The CSI was significantly related to the total FQOL (r = -0.610, p < 0.001), and with the physical (r = -0.472, p = 0.002), psychological (r = -0.418, p = 0.007) and sociological (r = -0.550 p < 0.001) scales; the association with the spiritual subscale did not reach statistical significance (r = -0.297, p = 0.063). The greater the effort of the caregiver, the worse quality of life.

Associations between ESAS and caregiving parameters

Total ESAS symptoms were significantly related to overall Pittsburgh score (r = 0.365, p = 0.028), the CSI (r = 0.45, p = 0.005) and total FQOL (r = 0.432, p = 0.009), but not to the duration of daily care (r = -0.152, p = 0.377). Table 4 presents bivariate correlations of ESAS and caregiving parameters.

There were no association between the time caring, or the time in palliative care and the outcome variables in the caregiver, nor with the patient’s symptom scale.

Discussion

In our study sample, most of the caregivers were women, confirming the pattern observed in previous studies [12, 33]. However, among the patients, the sexes were more evenly balanced [34]. In most cases, women continue to play the role of family caregiver. In our sample, all of the caregivers were family members, usually spouses or children [35] and on average dedicated extremely long hours to this task, exceeding 18 h a day [12].

When this study was conducted, the mean duration of palliative care for these patients was greater than four months, which suggests that in most cases early referral takes place, which is generally considered to reflect good patient care [3]. The types of cancer suffered by the patients in this study fitted the global pattern reported in this respect [36].

Among the patients in our study, the symptoms presented with greatest intensity were reduced wellbeing, fatigue, daytime sleepiness, depression, and simultaneous sleepiness and pain, which is in line with previous research findings [5, 7]. The mean scores obtained for the severity of these symptoms (4–6) reflect a moderate degree of intensity [32]. Whilst open to improvement, this level of symptoms is lower than that found in patients with similar clinical conditions who are not receiving palliative care [5].

Most of the caregivers were affected by strain, which was reflected in each of the variables studied. Over 75% of the caregivers reported suffering sleep disorders, a result that is similar to previous research findings [12, 20]. Such alterations provoke or aggravate problems such as anxiety, diabetes, obesity, heart disease and stroke [37,38,39].

A similar negative impact was reflected in the caregiver strain index, the score for which was significantly high for over 56% of the caregivers in our sample. This burden has been associated with increased anxiety and depression in previous literature [34, 35]. The caregiver strain compromised the total quality of life, also the physical, psychological and sociological scales,however, the association with the spiritual subscale did not reach statistical significance. Reflecting these consequences, the results for the caregivers’ overall quality of life, with an overall mean score of 52%, were also unsatisfactory [21].

These findings highlight the novel contribution made by our study, as little previous research has been undertaken regarding the association of symptoms of patients with advanced cancer on their caregivers’ quality of life. We show that a greater overall severity of symptoms suffered by patients with advanced cancer is related to worse quality of sleep for the caregiver. To our knowledge, only one previous study has considered such a relationship; in this case, the patient’s feeling of distress was directly associated with impairment of the caregiver’s sleep [40].

We also find that the greater severity of the patient’s symptoms is directly related to caregiver strain, which corroborates the findings of several prior studies in this regard [24, 41, 42]. Finally, the increased intensity of the patient’s symptoms is related to a poorer overall quality of life for the caregiver.

Overall, our study findings highlight the negative impact produced on the caregiver by the increasing severity of the patient’s condition, and underline the need to pay specific attention to helping the family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer receiving home palliative treatment. Our analysis of the relationship between the study variables considered for the patient-caregiver dyad shows that the caregiver benefits, indirectly, when the patient’s symptoms are alleviated.

This study has certain limitations that must be acknowledged. Firstly, the results obtained should be interpreted taking into account the cross-sectional nature of the study, which means that causality cannot be affirmed. Moreover, variables other than those included in the study may also influence the status of the family caregiver. Finally, the reliability of the analysis might be affected by the limited sample size of the caregiver-patient dyad in our analysis; this restriction arose from the difficulty encountered in recruiting suitable participants for the study, which in each case required the agreement of both the caregiver and the patient.

Further research should be conducted to design and develop interventions to improve the situation of patient-caregiver dyads when palliative home care is provided for patients with advanced cancer.

Conclusions

Family caregivers for patients with advanced cancer suffer negative consequences from the presence and intensity of these patients’ symptoms. Therefore, optimising the control of symptoms would benefit not only the patients but also their caregivers.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CSI:

-

Caregiver Strain Index

- ESAS:

-

Edmonton Symptom Assessment System

- FQOL:

-

Quality of Life Family Version

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

References

Wild CP, Weiderpass E, Stewart BW. World cancer report: cancer research for cancer prevention. International Agency for Research on Cancer: World Cancer Reports; 2020.

Hausner D, Tricou C, Mathews J, Wadhwa D, Pope A, Swami N, Hannon B, Rodin G, Krzyzanowska MK, Le LW, Zimmermann C. Timing of palliative care referral before and after evidence from trials supporting early palliative care. Oncologist. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/onco.13625.Advanceonlinepublication.doi:10.1002/onco.13625.

Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, Albreht T, Anderson R, Bruera E, Brunelli C, Caraceni A, Cervantes A, Currow DC, Deliens L, Fallon M, Gómez-Batiste X, Grotmol KS, Hannon B, Haugen DF, Higginson IJ, Hjermstad MJ, Hui D, Jordan K, Lundeby T. Integration of oncology and palliative care: a lancet oncology commission. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(11):e588–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7.

Komarzynski S, Huang Q, Lévi FA, Palesh OG, Ulusakarya A, Bouchahda M, Haydar M, Wreglesworth NI, Morère JF, Adam R, Innominato PF. The day after: correlates of patient-reported outcomes with actigraphy-assessed sleep in cancer patients at home (inCASA project). Sleep. 2019;42(10):zsz146. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsz146.

Lee G, Kim HS, Lee SW, Park YR, Kim EH, Lee B, Hu YJ, Kim KA, Kim D, Cho HY, Kang B, Choi HJ. Pre-screening of patient-reported symptoms using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System in outpatient palliative cancer care. Eur J Cancer Care. 2020;29(6):e13305. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13305.

Miceli J, Geller D, Tsung A, Hecht CL, Wang Y, Pathak R, Cheng H, Marsh W, Antoni M, Penedo F, Burke L, Ell K, Shen S, Steel J. Illness perceptions and perceived stress in patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer. Psychooncology. 2019;28(7):1513–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5108.

Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Moran SM, D’Arpino SM, Johnson PC, Lage DE, Wong RL, Pirl WF, Traeger L, Lennes IT, Cashavelly BJ, Jackson VA, Greer JA, Ryan DP, Hochberg EP, Temel JS. The relationship between physical and psychological symptoms and health care utilization in hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(23):4720–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30912.

Schulman-Green D, Feder SL, Dionne-Odom JN, Batten J, En Long VJ, Harris Y, Wilpers A, Wong T, Whittemore R. Family caregiver support of patient self-management during chronic, life-limiting illness: a qualitative metasynthesis. J Fam Nurs. 2021;27(1):55–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840720977180.

Seow H, Stevens T, Barbera LC, Burge F, McGrail K, Chan K, Peacock SJ, Sutradhar R, Guthrie DM. Trajectory of psychosocial symptoms among home care patients with cancer at end-of-life. Psychooncology. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5559.Advanceonlinepublication.doi:10.1002/pon.5559.

Yates P. Symptom management and palliative care for patients with cancer. Nurs Clin North Am. 2017;52(1):179–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2016.10.006.

Lee KC, Hsieh YL, Lin PC, Lin YP. Sleep Pattern and Predictors of Sleep Disturbance Among Family Caregivers of Terminal Ill Patients With Cancer in Taiwan: A Longitudinal Study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(8):1109–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909118755453

Lee KC, Yiin JJ, Lin PC, Lu SH. Sleep disturbances and related factors among family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Psychooncology. 2015;24(12):1632–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3816.

Moss KO, Douglas SL, Lipson AR, Blackstone E, Williams D, Aaron S, Wills CE. Understanding of health-related decision-making terminology among cancer caregivers. West J Nurs Res. 2020. 193945920965238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945920965238. Advance online publication.

Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, Litzelman K, Chou WY, Shelburne N, Timura C, O’Mara A, Huss K. Caring for caregivers and patients: research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016;122(13):1987–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29939.

Govina O, Vlachou E, Kalemikerakis I, Papageorgiou D, Kavga A, Konstantinidis T. Factors associated with anxiety and depression among family caregivers of patients undergoing palliative radiotherapy. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2019;6(3):283–91. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon_74_18.

Trevino KM, Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK. Advanced cancer caregiving as a risk for major depressive episodes and generalized anxiety disorder. Psychooncology. 2018;27(1):243–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4441.

Ekström H, Auoja NL, Elmståhl S, Sandin Wranker L. High burden among older family caregivers is associated with high prevalence of symptoms: data from the Swedish study “Good Aging in Skåne (GÅS).” J Aging Res. 2020;2020:5272130. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5272130.

Robinson CA, Pesut B, Bottorff JL. Supporting rural family palliative caregivers. J Fam Nurs. 2012;18(4):467–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840712462065.

Maltby KF, Sanderson CR, Lobb EA, Phillips JL. Sleep disturbances in caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Palliat Support Care. 2017;15(1):125–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951516001024.

Valero-Cantero I, Wärnberg J, Carrión-Velasco Y, Martínez-Valero FJ, Casals C, Vázquez-Sánchez MÁ. Predictors of sleep disturbances in caregivers of patients with advanced cancer receiving home palliative care: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;51:101907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2021.101907 Advance online publication.

Götze H, Brähler E, Gansera L, Schnabel A, Gottschalk-Fleischer A, Köhler N. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in family caregivers of palliative cancer patients during home care and after the patient’s death. Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27(2):e12606. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12606.

Oechsle K, Ullrich A, Marx G, Benze G, Wowretzko F, Zhang Y, Dickel LM, Heine J, Wendt KN, Nauck F, Bokemeyer C, Bergelt C. Prevalence and predictors of distress, anxiety, depression, and quality of life in bereaved family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2020;37(3):201–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909119872755.

Perpiñá-Galvañ J, Orts-Beneito N, Fernández-Alcántara M, García-Sanjuán S, García-Caro MP, Cabañero-Martínez MJ. Level of burden and health-related quality of life in caregivers of palliative care patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(23):4806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234806.

Tan JY, Molassiotis A, Lloyd-Williams M, Yorke, J. Burden, emotional distress and quality of life among informal caregivers of lung cancer patients: an exploratory study. Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12691.

Lyons KS, Lee CS. The association of dyadic symptom appraisal with physical and mental health over time in care dyads living with lung cancer. J Fam Nurs. 2020;26(1):15–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840719889967.

O’Hara RE, Hull JG, Lyons KD, Bakitas M, Hegel MT, Li Z, Ahles TA. Impact on caregiver burden of a patient-focused palliative care intervention for patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2010;8(4):395–404. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951510000258.

Valeberg BT, Grov EK. Symptoms in the cancer patient: of importance for their caregivers’ quality of life and mental health? Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(1):46–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2012.01.009.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4.

Arcos Imbachi DM. Validity and reliability of the quality of life instrument, family version in Spanish. Doctoral thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia de Bogotá D.C. E-File. 2010. http://www.core.ac.uk/download/pdf/11054017.pdf.

Robinson BC. Validation of a caregiver strain index. J Gerontol. 1983;38(3):344–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/38.3.344.

Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7(2):6–9.

Hui D, Bruera E. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System 25 years later: past, present, and future developments. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(3):630–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.370.

Washington KT, Parker D, Smith JB, McCrae CS, Balchandani SM, Demiris G. Sleep problems, anxiety, and global sef-rated health among hospice family caregivers. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018;35(2):244–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909117703643.

Ahmad Zubaidi ZS, Ariffin F, Oun C, Katiman D. Caregiver burden among informal caregivers in the largest specialized palliative care unit in Malaysia: a cross sectional study. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):186. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00691-1.

Unsar S, Erol O, Ozdemir O. Caregiving burden, depression, and anxiety in family caregivers of patients with cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;50:101882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101882 Advance online publication.

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Data source: Globocan 2018. Graph production: Global Cancer Observatory; 2020. http://www.gco.iarc.fr/.

Gong L, Liao T, Liu D, Luo Q, Xu R, Huang Q, Zhang B, Feng F, Zhang C. Amygdala changes in chronic insomnia and their association with sleep and anxiety symptoms: insight from shape analysis. Neural Plast. 2019;2019:8549237. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8549237.

Im E, Kim GS. Relationship between sleep duration and Framingham cardiovascular risk score and prevalence of cardiovascular disease in Koreans. Medicine. 2017;96(37):e7744. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000007744.

Steel JL, Cheng H, Pathak R, Wang Y, Miceli J, Hecht CL, Haggerty D, Peddada S, Geller DA, Marsh W, Antoni M, Jones R, Kamarck T, Tsung A. Psychosocial and behavioral pathways of metabolic syndrome in cancer caregivers. Psychooncology. 2019;28(8):1735–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5147.

Otto AK, Gonzalez BD, Heyman RE, Vadaparampil ST, Ellington L, Reblin M. Dyadic effects of distress on sleep duration in advanced cancer patients and spouse caregivers. Psychooncology. 2019;28(12):2358–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5229.

Govina O, Kotronoulas G, Mystakidou K, Katsaragakis S, Vlachou E, Patiraki E. Effects of patient and personal demographic, clinical and psychosocial characteristics on the burden of family members caring for patients with advanced cancer in Greece. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(1):81–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2014.06.009.

Semere W, Althouse AD, Rosland AM, White D, Arnold R, Chu E, Smith TJ, Schenker Y. Poor patient health is associated with higher caregiver burden for older adults with advanced cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;S1879–4068(21):00002–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2021.01.002 Advance online publication.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the participants and nurses that have made possible this study.

Funding

External funding for this study, involving research, development and innovation (R + D + I) in biomedical and health sciences in Andalusia (Spain), was obtained from the Regional Health Ministry of “Junta de Andalucia”, under Project AP-0157–2018, dated November 13, 2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IVC, CC and MAVS participated in the design of the study. IVC, YCV, FJMV and MAVS selected relevant measures and collected data. CC, FJBL and MAVS performed the statistical analysis. IVC and MAVS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Malaga Provincial Ethics Committee, project code AP-0157–2018. The patients and their caregivers participated in the study voluntarily, were fully informed about its nature and purpose, and provided written consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Valero-Cantero, I., Casals, C., Carrión-Velasco, Y. et al. The influence of symptom severity of palliative care patients on their family caregivers. BMC Palliat Care 21, 27 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-00918-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-00918-3