Abstract

Background

Nurses have an essential role in providing high-quality palliative care to patients and their families. Hence, they require adequate palliative care education. However, there is only limited insight into how final-year nursing students perceive palliative care education in undergraduate nursing programs. This study aimed to describe nursing students’ perspectives of the development needs of palliative care education. An additional two aims emerged based on the collected data, namely, to describe the preferred education for palliative care and the factors which promote or hinder palliative care learning during undergraduate nursing studies.

Methods

The research was guided by a descriptive qualitative approach and applied inductive content analysis. The frequencies (f) of identified codes (reduced expressions) were counted to show the noteworthiness of each category in relation to the entirety. The participants were final-year nursing students (n = 766) who had participated in a national survey.

Results

The inductive content analysis identified three unifying categories. The first was ‘Development needs and views of palliative care education’ (f = 524), which consisted of the main categories ‘the need to develop palliative care education’ (f = 414) and ‘meaning of palliative care and its education’ (f = 110). Secondly ‘Preferred types of palliative care education’ (f = 1379), including the main categories ‘teaching contents in palliative care education’ (f = 905), ‘teaching methods for palliative care learning’ (f = 393), and ‘placement of palliative care studies’ (f = 81). Thirdly ‘The facilitators and barriers to palliative care learning’ (f = 401), consisting of the main categories ‘factors facilitating palliative care learning’ (f = 66) and ‘barriers to palliative care learning’ (f = 335).

Conclusions

This study provides detailed information about nursing student’s perspectives of palliative care education and its development needs. Hence, the results are relevant to decision-makers who want to develop undergraduate nursing curricula. This study highlights that palliative care education should be developed by ensuring that all students have equal access to palliative care education provided by highly competent teachers. Possibilities for clinical placements or visits to palliative care units during the education should also be improved. The participating students felt unprepared to provide high-quality palliative care even though they responded that palliative care is an important topic in their nursing studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

The need to develop palliative care education was highlighted by the Council of Europe (CoE) during an assembly in 2018. Access to palliative care should be a human right and, therefore, the provision of palliative care should be integrated into the health care system [1]. Furthermore, education is one of the core components in the World Health Organization’s public health strategy to successfully integrate palliative care into health care [2, 3] and has also been reported to facilitate the development of palliative care [4]. Several contemporary phenomena, i.e., an aging world population, the increase in noncommunicable diseases, and the emergence of novel viruses, recently highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, demonstrate that there is an immense demand for palliative care, which is expected to double by 2060 [5].

Nurses, as the largest occupational group in health care, have an essential role in ensuring high-quality care [6]. Nurses are also the primary providers of palliative care for patients and their families in many different contexts [6,7,8]. Hence, they should have sufficient palliative care education and competencies to provide high-quality palliative care [5, 9, 10].

To ensure that all nurses possess the required palliative care competencies, undergraduate nursing education should cover palliative care [11, 12]. Nevertheless, previous research has reported that undergraduate nursing students lack competence to provide palliative care [13, 14] and feel unprepared for palliative care and encountering death [15,16,17].

The need to develop palliative care education has previously been highlighted [18]. For example, the European Association for Palliative Care task force group published a report focusing specifically on the development of palliative care in nursing education [19]. Although this report is known in the European countries, there is still large variety in palliative care education both across and within countries. Notably, over half of European countries (56%) reported in a recent survey that palliative care was not a mandatory subject in undergraduate nursing education [20]. In Finland, universities of applied sciences (UASs) largely vary in terms of how palliative care is covered in undergraduate nursing programs. As a result, the recent statement of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health includes recommendations for how Finnish nursing education should be developed [21].

Previous evidence has shown that palliative care education increases nursing students’ knowledge of palliative care and positively influences their attitudes towards end-of-life care [18, 22,23,24]. Furthermore, palliative care education promotes students’ personal growth and self-awareness [25]. The need to integrate palliative care into undergraduate education has been emphasized before, with attempts at including this part of care into nursing curricula intensifying during the last 10 years [18]. Nevertheless, there is still an evident need to develop the extent to which palliative care is integrated into undergraduate nursing education [11, 18, 20, 21].

Most of the qualitative research on the topic of palliative care in nursing education published in the last 10 years has focused on students’ experiences of different teaching interventions, e.g., simulations or elective courses [26, 27], and students’ perspectives or attitudes towards end-of-life care or care for the dying patients [28, 29]. To our knowledge, there is only limited qualitative evidence of final year nursing students’ perspectives of the development needs in palliative care education in undergraduate nursing programs and how this area of care could be better integrated into the nursing curriculum.

Methods

This study aimed to describe nursing students’ perspectives of the development needs of palliative care education. An additional two aims emerged based on the collected data, namely, to describe the preferred education for palliative care and the factors which promote or hinder palliative care learning during undergraduate nursing studies. The research applied a descriptive qualitative approach with an inductive content analysis method [30]. The intention of the study was to present a comprehensive summary of the phenomenon of interest without claiming any methodological roots [31].

Settings

The study was performed across all of the Finnish UASs (n = 21) providing an undergraduate nursing program. In Finland, all registered nurses are required by law to have completed a Bachelor’s degree nursing program from a UAS [32]. After graduation the registered nurses need to apply for licensing to work as a nurse in Finland. The Bachelor’s degree program lasts approximately three-and-a-half years and comprises 210 European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) credits and fulfills the criteria of the European Union Directive 2013/55/EU [33]. The education includes 90 ECTS of clinical training. The education is free-of-charge and is funded by the Ministry of Culture and Education. The nursing teacher’s educational requirements are also regulated by law, e.g., they must hold a Master’s degree and have at least 3 years of working experience in the nursing field [34].

The UASs have autonomy in developing the undergraduate nursing curriculum. However, criteria set by the European Union [33] and a national consensus-based report of nursing competencies published in 2015 [35], and renewed in 2020 [36], serve as a framework for curriculum development. The renewed report of competencies includes palliative care, which was not so clearly addressed in the previous version. Registered nurses can deepen their competencies according to their own interests during their undergraduate nursing studies by choosing courses in the limits of the curriculum. Still, when graduating they all are registered nurses without specialization.

Participant characteristics and data collection

The data were collected as part of a larger national cross-sectional survey that targeted undergraduate nursing students. The inclusion criteria for participation were that the student is in the final year of studies and is enrolled in nursing degree program in a Finnish UAS provided in either of the official languages in Finland (Finnish or Swedish). Detailed participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Data collection ran from September 2018 to March 2019. The participants consisted of a convenience sample of final year nursing students studying in a UAS at the time of data collection. Convenience sampling is a commonly used sampling method when recruiting participants from a particular setting. The sampling method aims to provide a group of participants with experience of the study phenomenon. In this study, the setting was UASs and the participants were final year nursing students, who had sufficient experience with nursing education to evaluate the development needs of palliative care education [31].

Each UAS named a contact person who would perform the data collection. In 19 of the UASs, the contact person (first author in two UAS) distributed the paper questionnaire to final-year nursing students during a teaching session in a classroom, with the students answering the questionnaire during this session. In two UASs, students responded to the questionnaire online through a link sent via email to the student group by the contact person, with one follow-up message sent later to remind the students to complete the questionnaire. An information letter containing the study purpose, researchers’ contact information, including a description of their occupation, academic position, and interest in developing palliative care education, was attached to the survey. The students responded to the questionnaire completely anonymously, with no personal data being collected and no prior relationship was established between the researchers and any of the students.

The contact persons estimated that there were 1868 final-year students studying at the time when the questionnaire was provided to the student groups. A total of 1331 students gave an eligible response to the survey, of which 766 (57,6%) answered the open-ended, qualitative question included in this sub-study. The survey included six background questions, questions of students view of the palliative care contents provided in nursing studies and their self-assessed competence about palliative care, and an open-ended question: “Tell your thoughts on how palliative care education should be developed”. The data of this sub-study consisted of students written answers to this open-ended question. The length of the students written answers varied from one sentence to half of a Microsoft Word A4 page. The questions were developed by the authors. The clarity of the questionnaire was pretested by one student group (n = 15), no amendments were required based on the pretest. Information covering the characteristics and relevant experience of the authors can be found in Table 2.

Data analysis

The qualitative analysis was performed by an inductive content analysis method, in which categories emerge from the data and no theoretical framework is used as a starting point [30, 37]. The students’ responses (only manifest content) were analyzed to describe the phenomenon of interest. Words, sentences, or phrases which constructed a meaning were used as the unit of analysis [30]. No software was used in the analysis process.

In the first phase of analysis, the data were transcribed verbatim from the questionnaires to a Microsoft Word template, after which the researchers carefully read through the resulting data several times to become familiar with the content. During this phase of the analysis, the researchers noticed that the students’ responses reflected the development needs of palliative care education; moreover, they also provided their preferences for how the education should be delivered, along with factors that promoted or hindered their learning. In qualitative research it is possible that the aim and research question can change during the analysis process, i.e., the data direct the process [30]. Therefore, the aims of the present study were expanded to cover students’ preferences for how palliative care education should be provided and which factors promote or hinder their learning.

In the second phase of the analysis, the original data were reduced to codes, which were relevant to the study aims. In the third phase of the analysis, the reduced codes were grouped together based on similarities in content. The fourth phase of the analysis was data abstraction, i.e., sub-categories, categories, main categories and unifying categories were formed based on the grouped codes. The identified categories were inductively derived from the data, while the abstraction was performed in a way that it applied to all data [30, 37]. An example of the coding process is provided in Table 3.

The coding process was performed by one of the authors (blinded), after which all other members of the research group went through the results. Once consensus was achieved, the first author performed the categorization and abstraction of the data, which was again critically assessed by all members of the research group. The frequencies (f) of codes (reduced expressions) were counted to show the noteworthiness of each category in relation to the entirety. The collected data yielded a total of 2304 codes. Data saturation, which is the point at which no further data collection is necessary, was achieved during the analysis process [38]. The research adhered to COREQ guidelines (Additional file 1) for the reporting of qualitative research [39].

Ethical consideration

The standards of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed during each step of the study [40]. Each participating UAS (n = 21) granted a written study permission for the data collection. Before starting data collection, the Ethical Committee of North Ostrobothnia’s Hospital District was consulted regarding the need for a separate ethical statement. It was not needed since, according to Finnish law, a statement is not required when the study does not intervene with participants’ integrity [41]. The participants were informed about the voluntary nature of participation in the study and received written information about the study aims. Each student responded that they had read the information letter and agreed to participate in the study by answering ‘yes’ to a question of this issue. If the question was left unanswered or the answer was ‘no’, the response was rejected. The researchers’ contact information was included in the information letter in case of questions or concerns of the students related to the study. Since data collection was anonymous, no personnel register was formed in the study and anonymity was protected so that the student cannot be identified through the examples of authentic data presented in the study [42].

Results

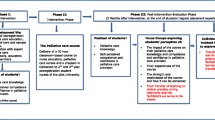

Three unifying categories were identified, namely, 1) development needs and views of palliative care education (f = 524), 2) the preferred types of palliative care education (f = 1379), and 3) factors that promote or hinder palliative care learning (f = 401) (Fig. 1). Each subcategory presented below will include one quotation as an example.

Development needs and views of palliative care education

This unifying category included two main categories: ‘The need to develop palliative care education’ (f = 414); and ‘Meaning of palliative care and its education’ (f = 110) (Table 4).

The main category ‘The need to develop palliative care education’ (f = 414) included three categories and 14 subcategories. In this main category, most codes fell under the category ‘More palliative care education in general’ (f = 270), which included six subcategories. The subcategories which included the most codes were ‘More palliative care education’ (f = 175) and ‘More resources to palliative care education’ (f = 36). The students also felt that equal access to palliative care education, i.e., ‘Obligatory course available to all students’ (f = 16), was an important area of development. Some examples of the original data are:

“Definitely more education about this topic into the nursing degree!” 414.

“More time resources should be given to palliative care teaching.” 1136.

“A separate obligatory own course to all (students) about palliative nursing.” 312

The main category ‘Meaning of palliative care and its education’ (f = 110) consisted of three categories and 13 subcategories. The category that included the most codes was ‘Importance of palliative care education’ (f = 55), which included four subcategories, while the subcategory with the most codes was ‘palliative care is an important topic’ (f = 40). Additional subcategories that included numerous codes were: ‘palliative care education should be an essential part of nursing education’ (f = 5); and ‘palliative care should be one of the most important topics in education’ (f = 5). The students expressed the following:

“In my opinion palliative care is a very important topic for nurses.” 739

“Palliative nursing is an essential part of education, and it is important to gain knowledge about it.” 874

“This subject should be one of the most important to learn about, so that you can feel safe and know what to do when you are in the situation.” w13

Preferred types of palliative care education

This unifying category included three main categories, namely, ‘Teaching contents in palliative care education (f=905), ‘Teaching methods for learning palliative care’ (f = 393), and ‘Placement of palliative care studies (f = 81), see Table 5.

The main category ‘Teaching contents in palliative care education’ (f = 905) included 18 categories and 78 subcategories. The category with most codes was ‘Encounters in palliative care’ (f = 162), which consisted of five subcategories, with the subcategories ‘guidance to encounter the closest ones’ (f = 72) and ‘guidance to encounter the patients’ (f = 59) including the most codes. The students also highlighted the need for more ‘theory and practice of palliative care encounters’ (f = 16). The students shared the following:

“Education of how we as nurses can encounter… the closest ones.” 1135

“More education of encounters with dying patients.” 561

“It would be good to get more theory and advice concerning humane encounters.” 101

The main category ‘Teaching methods for learning palliative care’ (f = 393) consisted of six categories and 25 subcategories. The category that included the most codes was ‘Patient cases and collaboration with working field in teaching’ (f = 146), and it included five subcategories. The three subcategories with the most codes demonstrated which aspects of teaching the students preferred, namely, teachers ‘using concrete examples from practice’ (f = 56), lectures provided by experts in the field (f = 31), and ‘visits to hospice or palliative care wards’ (f = 26). As examples, the students stated the following:

“To orientate with palliative care, concrete examples from the working environment should be used so that it could be concretely understood.” 308

“An experienced end-of-life / palliative care professional could come and talk about the topic.” 684

“… by visiting hospice and palliative care units during the education.” 198

The main category ‘Placement of palliative care studies’ (f = 81) consisted of three categories and 11 subcategories. The category which included the most codes was ‘Integrated and unifying palliative care education in the curriculum’ (f = 35), which included five subcategories. The subcategories with the most codes highlighted various aspects of palliative care learning, namely, ‘repeated teaching at different phases of education’(f = 12), ‘education as an own entirety’ (f = 8), and ‘palliative care education should be a natural part of all education’ (f = 6), which highlighted how palliative care could be integrated into undergraduate nursing studies.

“The topic could be repeated during the nursing studies.” 282.

“It should also be one own teaching entity, where discussion about the topic will be made.” 337

“It could be a small part of every teaching session, making it “naturally” applicable to working life.” 618

Factors that promote or hinder palliative care learning

This unifying category included two main categories: ‘Factors that facilitate palliative care learning’ (f = 66); and ‘Barriers to palliative care learning’ (f = 335) (Table 6).

The main category ‘Factors facilitating palliative care learning’ included three categories and nine subcategories. The category with the most codes was ‘Previous clinical experience about palliative care’ (f = 31); under this category the subcategory ‘palliative care clinical practice’ (f = 15) included the most codes. The students also expressed that ‘work experience from clinical settings’ (f = 14) and the possibility to achieve ‘mentoring in clinical practice (f = 2) were conducive to palliative care learning. The students expressed:

“I have completed my clinical practice in a hospice, and it was an eye-opening learning experience.” w41

“Palliative care and end-of-life care have become familiar to me when working as a nurse during my studies.” w32

“Good instructors in working life and clinical practice taught me a lot.” 1113

The main category ‘Barriers to palliative care learning’ included seven categories and 31 subcategories. The category that included the most codes was ‘Insufficient amount of education’ (f = 119), which included four subcategories. The following subcategories included the most codes: ‘too little education of palliative care’ (f = 92); ‘too superficial education’ (f = 14) and ‘ no education of palliative care’ (n = 7) Some original expressions under:

“There is too little palliative care education during the studies.” 48

“The teaching of palliative nursing was too superficial.”302

“ … I did not receive any education of palliative care” 68

Discussion

The participating students expressed their perspectives of both the current state of palliative care education and the development needs for this aspect of nursing education. The students often shared that undergraduate nursing studies should generally include more palliative care education. These perspectives can reflect to the variation of the palliative care education in the Finnish UASs [21]. It is noteworthy that the students regarded palliative care education as an important and essential topic which should be integrated into the nursing curriculum. As palliative care should be incorporated in the early stages of caring for a person with a chronic illness based on the need not on the diagnosis, prognosis or settings of care, it is most likely that nurses encounter palliative care patients during their career [5]. Therefore, it is important that all students would be prepared for the care when graduating. The students highlighted the importance of practical aspects of palliative care, i.e., knowledge of how to manage encounters with patients, which can be gained by meeting real patients and being taught by experts from the field such as specialist nurses and physicians. In general, the education delivered by experts from the field should be better utilized, since this probably differs between the UASs in Finland.

The students also expressed their views of which types of palliative care education they preferred. Notably, the students described various aspects of palliative care that they hoped should be integrated into nursing education. This may reflect the wide range of competences nurses need to provide high-quality palliative care. The palliative care aspects mentioned by students agree with earlier descriptions of palliative care competences [19, 43,44,45,46,47]. In addition to the content of palliative care education, the students specified which teaching methods they preferred. Earlier literature has confirmed that various methods are effective at enhancing students’ palliative care learning [22, 23, 48], with this study providing a unique, detailed view of which aspects of palliative care and which teaching methods they prefer.

The undergraduate nursing students also shared their views of which factors promote and hinder their palliative care learning. They expressed that clinical practice in palliative care settings and mentoring by experienced nurses facilitate the learning process. A supportive mentor-student relationship, including guidance and role-modelling, has been identified to facilitate students’ clinical learning [49], while other research has stated that staff support is crucial to good learning experiences [17, 50]. First-hand experience in caring for dying persons was found to be associated with positive attitudes towards end-of-life care [51]. For students to gain positive learning experiences about palliative care, they should be afforded more opportunities to attend clinical practice placements and receive instruction and support from experts in the field. This is essential, since students also expressed that staff members with insufficient palliative care competences can hinder learning.

Another subject which was reported to be both a facilitator and barrier to learning was the teacher’s competence, i.e., a competent teacher facilitated the learning process while incompetent teachers served as a barrier to learning. Student expressed that a competent teacher has due-to-date knowledge of palliative care and experience of the subject to share concrete examples to the students. Competent teachers are also wished to have an open and supporting attitude to the students’ feelings and concerns of the subject. The importance of a competent educator has been highlighted in a European guide for the development of palliative nurse education [19]. Furthermore, previous studies have also stated that teachers need additional palliative care education [52] and that the lack of competent teachers can significantly hinder high-quality education [53]. Hence, educational institutions should assess and ensure the competence of teaching staff, as this is related to the quality of undergraduate nursing education.

The students also identified feelings of unpreparedness and fear of the topic as barriers to learning. Unpreparedness, feelings of vulnerability and fear have also been reported in earlier research [24, 54, 55]. The expression of uncertainty and feelings of unpreparedness can often be explained by insufficient experience and the lack of education [17, 56,57,58]. The barriers to learning reported by the undergraduate nursing students participating in this study revealed certain areas of palliative care education which must be improved in nursing curricula.

Some future implications for research were identified during the study. This study concerned final-year students, who may have limited understanding of all needs of the education to prepare them to the future work with palliative care patients. Therefore, as a future implication for research it would be important to focus also on graduated nurses. This study gave a comprehensive summary of the phenomenon, hence, to get a more in-depth view of the phenomenon face-to face or focus-group interviews would further bridge the gaps in the knowledge of the palliative nursing education. In addition, relatively little is known about teachers’ competence and requirements to provide quality palliative care education. Even though this was identified as a facilitating or hindering factor in learning palliative care by the students, more focus on this should be put in future research.

This study gave a comprehensive summary of nursing students views of palliative care education development needs. The research also provides information on what factors should be changed or strengthen to improve students learning. The results can be utilized when developing the undergraduate nursing curriculum. This study gives information of the preferred placement of the education, namely thorough the nursing education. In addition, it provides an overview of students’ perceptions of the preferred teaching contents and methods. It calls to increase the amount of palliative care education and for more research of the phenomenon, as well.

Strengths and limitations

Several aspects strengthened the trustworthiness of this study. The chosen method was suitable for the purpose of this study. Moreover, data saturation was achieved during the analysis [38]. The credibility was strengthened by reporting in detail the sampling, data collection and analysis process. The clarity of the open-ended question was pretested, and the sample included final-year nursing students from all UASs across Finland. Therefore, it can be assumed that the study population had experiences of the achieved palliative care education in nursing studies. Furthermore, dependability was strengthened by presenting an example of the analysis process (Table 3) and tables and figures of categories identified through content analysis (Tables 4, 5 and 6, Fig. 1). It should also be noted that the researchers constantly discussed the analysis and findings throughout the study. Confirmability was strengthened by focusing on the manifest content so that the results would represent the views of the students [37]. The participants represented students from all UASs and the data was rich which made it possible to make a comprehensive summary of the phenomenon, which strengthen the transferability of the results. In addition, the sampling and inclusion criteria are described carefully in the manuscript. The authenticity of the results was strengthened by providing authentic citations from the collected data [30, 59].

The research also included certain limitations which could weaken the trustworthiness of the study. For instance, the questionnaire was answered anonymously, and answering the open-ended question was completely voluntary. Hence, it is impossible to know the reason(s) why certain students refused to answer this question. Furthermore, there was no possibility to ask any further questions from the students or return the findings to the students for comments or corrections [30]. In addition, because the students were not yet graduated, they may not possess all the understanding of what their future competence needs would be when caring for patients in palliative care, which can lead to a limited vision of the education needs. It should also be noted that several subcategories consisted of a small number of codes; however, they are important because they show different aspects of the studied phenomenon.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that palliative care education in undergraduate nursing curricula still needs to be developed in terms of the amount, content, methods and integration into the programs. The students’ responses revealed feelings of unpreparedness to provide palliative care even though the nursing students highlighted the importance of palliative care as a topic in their education. Students should have enhanced access to clinical placements or visits to palliative care units to facilitate their learning of palliative care. Furthermore, a teacher’s competence is also linked to the students’ learning processes. This study gives detailed information about nursing students’ perspectives on palliative care education. Based on the results of this study, we suggest that final-year nursing students should gain valuable insight into different aspects of palliative care through their nursing education, and this can be ensured by using effective teaching methods. Therefore, the presented results are of great value to professionals and decision-makers who are planning to integrate palliative care into the undergraduate nursing curriculum.

Availability of data and materials

The original data of the current study are not publicly available due to the terms of the achieved research permits from the UASs and to ensure the study participants that the data will be retained confidential. Within the limits of confidentiality, more detailed, but anonymous, data is available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- UAS:

-

University of Applied Sciences

References

Council of Europe. The provision of palliative care in Europe. Parliamentary assembly. Council of Europe. Resolution 2249. 2018. http://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/Xref-XML2HTML-en.asp?fileid=25214&lang=en; Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

Stjernswärd J, Foley KM, Ferris FD. The public health strategy for palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2007;33(5):486–93.

Stjernswärd J. Palliative care: the public health strategy. J Public Health Pol. 2007;28(1):42–55.

Centeno C, Garralda E, Carrasco JM, den Herder-van der Eerden M, Aldridge M, Stevenson D, et al. The palliative care challenge: analysis of barriers and opportunities to integrate palliative care in Europe in the view of national associations. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(11):1195–204.

Connor S. Global Atlas of Palliative Care, 2nd. Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance and World Health organization. London; 2020. http://www.thewhpca.org/resources/global-atlas-on-end-of-life-care. Accessed 30 Dec 2021.

WHO. State of world’s nursing. Investing in education, jobs and leadership. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279. Accessed 14 Jul 2021.

Fitch MI, Fliedner MC, O’Connor M. Nursing perspectives on palliative care 2015. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4:150–5.

International Society of Nurses in Cancer Care. Models of palliative care position statement. 2017. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.isncc.org/resource/resmgr/position_statements/isncc_models_of_palliative_c.pdf. Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

Gamondi C, Larkin P, Payne S. Core competencies in palliative care: an EAPC white paper on palliative care education - part 1. Eur J Palliat Care. 2013a;20(2):86–91.

Gamondi C, Larkin P, Payne S. Core competencies in palliative care: an EAPC white paper on palliative care education - part 2. Eur J Palliat Care. 2013b;20(3):140–5.

Arias-Casais N, Garralda E, Rhee J, Lima L, Pons JJ, Clark D, et al. EAPC atlas of palliative care in Europe. Vilvoorde: EAPC Press. 2019. http://hdl.handle.net/10171/56787. Accessed 10 Apr 2021.

World Health Assembly. Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course. 2014. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_R19-en.pdf. Accessed 25 Jun 2021.

Dobrowolska B, Mazur E, Pilewska-Kozak A, Donka K, Kosicka B, Palese A. Predicted difficulties, educational needs, and interest in working in end of life care among nursing and medical students. Nurse Educ Today. 2019;83:104194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.08.012.

Chover-Sierra E, Martínez-Sabater A. Analysis of Spanish nursing students’ knowledge in palliative care. An online survey in five colleges. Nurse Educ Pract. 2020;49:102903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102903.

Malone L, Anderson J, Croxon L. Are newly graduated nurses ready to deal with death and dying? - a literature review. Nurs Palliat Care. 2016;1(4):89–93. https://doi.org/10.15761/NPC.1000123.

Croxon L, Deravin L, Anderson J. Dealing with end of life—new graduated nurse experiences. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:337–44.

Ek K, Westin L, Prahl C, Osterlind J, Strang S, Bergh I, et al. Death and caring for dying patients: exploring first-year nursing students’ descriptive experiences. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2014;20(10):509–15.

Cavaye J, Watts J. An integrated literature review of death education in pre-registration nursing curricula: key themes. Int. J Palliat Care. 2014;564619. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/564619.

De Vlieger M, Gorchs N, Larkin P, Porchet F. A guide for the development of palliative nurse education in Europe. 2004. https://www.eapcnet.eu/DesktopModules/EasyDNNNews/DocumentDownload.ashx?portalid=0&moduleid=1207&articleid=408&documentid=37. Accessed 15 Jan 2019.

Martins Pereira S, Hernández-Marrero P, Pasman HR, Capelas ML, Larkin P, Francke A. EAPC taskforce on preparation for practice in palliative care nursing across the EU. Nursing education on palliative care across Europe: results and recommendations from the EAPC taskforce on preparation for practice in palliative care nursing across the EU based on an online-survey and country reports. Palliat Med. 2021;35(1):130–41.

Saarto T, Finne-Soveri H, Expert working groups. Recommendation on the provision and improvement of palliative care services in Finland. Final report of the expert. Reports and Memorandums of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health 2019:68. (Abstract in English). 2019. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-00-4126-7. Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

Hökkä M, Rajala M, Kaakinen P, Lehto J, Pesonen H-M. The effect of teaching methods in palliative care education for undergraduate nursing and medical students - a systematic review. Int J Palliat Nurs Accepted. 2021;15:2.

Lippe M, Carter P. End-of-life care teaching strategies in prelicensure nursing education. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2015;17(1):31–9.

Gillan P, van der Riet P, Jeong S. End of life care education, past and present: a review of the literature. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34:331–42.

Ballesteros M, Centeno C, Arantzamendi M. A qualitative exploratory study of nursing students' assessment of the contribution of palliative care learning. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34:e1–6.

Hjelmfors L, Strömberg A, Karlsson K, Olsson L, Jaarsma T. Simulation to teach nursing students about end-of-life care. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2016;18(6):512–8.

Hold JL, Blake BJ, Ward EN. Perceptions and experiences of nursing students enrolled in a palliative and end-of-life nursing elective: a qualitative study. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(6):777–81.

Österlind J, Prahl C, Westin L, Strang S, Bergh I, Henoch I, et al. Nursing students' perceptions of caring for dying people, after one year in nursing school. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;41:12–6.

Juvet TM, Bornet M-A, Desbiens J-F, Tapp D, Roos P. “Do not protect us, train us”—Swiss healthcare students’ attitudes toward caring for terminally ill patients. OMEGA J Death Dying. 2021:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228211007003.

Kyngäs H, Mikkonen K, Kääriäinen M. The application of content analysis in nursing science research. Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2019.

Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research. Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

Act on health care professionals (559/1994). http://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/1994/19940559. Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

European Parliament and the Council. Directive 2013/55/EU. 2013. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2013:354:0132:0170:en:PDF. Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

Valtioneuvoston asetus ammattikorkeakouluista. 1129/2014. 2014. Finlex. https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2014/20141129#Pidp446305600. Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

Eriksson E, Korhonen T, Merasto M, Moisio E-L. Sairaanhoitajan ammatillinen osaaminen - Sairaanhoitajakoulutuksen tulevaisuus -hanke. Kuopio: Bookwell Oy; 2015. https://www.epressi.com/media/userfiles/15014/1442254031/loppuraportti-sairaanhoitajan-ammatillinen-osaaminen.pdf. Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

Silen-Lipponen M, Korhonen T. Osaamisen ja arvioinnin yhtenäistäminen sairaanhoitajakoulutuksessa – yleSHarviointi-hanke. Savonia-ammattikorkeakoulun julkaisusarja 5/2020. 2020. https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/347289/2020-5yleshArviointi.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107–15.

Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52:1894–907.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Graig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health C. 2007;19:349–57.

National Library of Medicine. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–4.

Finnish Medical Research Act of 488/1999. Finlex. https://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/1999/en19990488. Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016. General Data Protection Regulation 2016. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj. Accessed 18 Jun 2021.

Hökkä M, Martins Pereira S, Pölkki T, Kyngäs H, Hernández-Marrero P. Nursing competencies across different levels of palliative care provision: a systematic integrative review with thematic synthesis. Palliat Med. 2020;34:851–70.

Hökkä M, Melender H-L, Lehto J, Kaakinen P. Palliative nursing competences aligned to different levels of palliative care provision: a qualitative analysis of the professional’s perspective. J Palliat Med. 2021; https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/jpm.2020.0632.

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Preparing graduate nursing students to ensure quality palliative care for the seriously ill & their families 2018. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/ELNEC/PDF/Graduate-CARES.pdf. Accessed 9 Jan 2021.

Ferrel B, Malloy P, Mazanec P, Virani R. Cares: AACN's new competencies and recommendations for educating undergraduate nursing students to improve palliative care. J Prof Nurs. 2016;32:327–33.

Ryan K, Connolly M, Charnley K, et al. Palliative Care Competence Framework. Dublin: Health Service Executive; 2014. http://aiihp.corg/education/competence. Accessed 15 Feb 2021.

Ruiz-Pellóna N, Sarabia-Cobo C, Amo-Setien F, Fernandez-Pena R, Abajas R, Martin R, et al. Experiences of nursing students participating in end-of-life education programs: a systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;90:104442.

Gorchs-Font N, Ramon-Aribau A, Yildirim M, Kroll T, Larkin P, Subirana-Casacuberta M. Nursing students’ first experience of death: identifying mechanisms for practice learning. A realist review. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;96:104637.

Connell S, Yates P, Barrett L. Understanding the optimal learning environment in palliative care. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31:472–6.

Grubb C, Arthur A. Student nurses' experience of and attitudes towards care of the dying: a cross-sectional study. Palliat Med. 2016;30(1):83–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315616762.

Brajtman S, Fothergill-Bourbonnais F, Fiset V, Alain D. Survey of educators’ end-of-life care learning needs in a Canadian baccalaureate nursing programme. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2009;15(5):233–41.

Josephsen J, Martz K. Faculty and student perceptions- an end-of-life nursing curriculum survey. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2014;16(8):474–81.

Bailey C, Hewison A. The impact of a ‘critical moments’ workshop on undergraduate nursing students’ attitudes to caring for patients at the end of life: an evaluation. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(23–24):3555–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12642.

Henoch I, Melin-Johansson C, Bergh I, Strang S, Ek K, Hammarlund K, et al. Undergraduate nursing students’ attitudes and preparedness toward caring for dying persons – a longitudinal study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2017;26:12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2017.06.007.

Ablett JR, Jones RS. Resilience and well-being in palliative care staff: a qualitative study of hospice nurses’ experience of work. Psycho Oncol. 2007;16(8):733–40.

Strang S, Bergh I, Ek K, Hammarlund K, Prahl C, Westin L, et al. Swedish nursing students’ reasoning about emotionally demanding issues in caring for dying patients. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2014;20(4):194–200.

Jiang Q, Lu Y, Ying Y, Zhao H. Attitudes and knowledge of undergraduate nursing students about palliative care: an analysis of influencing factors. Nurse Educ Today. 2019;80:15–21.

Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, Pölkki T, Utriainen K, Kyngäs H. Qualitative content analysis: a focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open. 2014;4:1–10.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the nursing students who participated in this study.

Funding

The data collection was funded by EduPal- project, which was funded by the Ministry of Education and Culture (Decision 29.3.2018 OKM/258/523/2017) in Finland. The writing of the manuscript and the open access fee was granted by Durchman foundation as a personal research grant for the first author. The funders had no role in the design of this study, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript. The content of this article reflects only the authors views and the funders are not liable for of the information contained in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H., J.T.L., H.K and T.P. designed the study methodology. M.H. and J.T.L. collected the data. M.H., J.T.L., H.K and T.P. analyzed the data and drafted and revised the manuscript. Furthermore, all the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The standards of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed during each step of the study [40]. The Ethical Committee of North Ostrobothnia’s Hospital District was consulted before data collection, they stated that formal approval was not needed for this study. It was not needed since, according to the Finnish law, a statement is not required when the study does not intervene with participants’ integrity [41]. Participation in the study was voluntary and an informed consent was obtained from all participants, each student responded that they had read the information letter of the research and agreed to participate in the study by answering to a question of this issue. All research material was coded with numbers, not with the personal details of the students to reassure the confidentiality for the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

COREQ- checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hökkä, M., Lehto, J.T., Kyngäs, H. et al. Finnish nursing students’ perceptions of the development needs in palliative care education and factors influencing learning in undergraduate nursing studies – a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care 21, 40 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-00915-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-00915-6