Abstract

Background

Antithrombotics are frequently prescribed for patients with a limited life expectancy. In the last phase of life, when treatment is primarily focused on optimizing patients’ quality of life, the use of antithrombotics should be reconsidered.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of a retrospective review of 180 medical records of patients who had died of a malignant or non-malignant disease, at home, in a hospice or in a hospital, in the Netherlands. All medication prescriptions and clinical notes of patients using antithrombotics in the last three months of life were reviewed manually. We subsequently developed case vignettes based on a purposive sample, with variation in setting, age, gender, type of medication, and underlying disease.

Results

In total 60% (n=108) of patients had used antithrombotics in the last three months of life. Of all patients using antithrombotics 33.3 % died at home, 21.3 % in a hospice and 45.4 % in a hospital. In total, 157 antithrombotic prescriptions were registered; 30 prescriptions of vitamin K antagonists, 60 of heparins, and 66 of platelet aggregation inhibitors. Of 51 patients using heparins, 32 only received a prophylactic dose. In 75.9 % of patients antithrombotics were continued until the last week before death. Case vignettes suggest that inability to swallow, bleeding complications or the dying phase were important factors in making decisions about the use of antithrombotics.

Conclusions

Antithrombotics in patients with a life limiting disease are often continued until shortly before death. Clinical guidance may support physicians to reconsider (dis)continuation of antithrombotics and discuss this with the patient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Antithrombotics are frequently prescribed to patients with a life-limiting disease [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. They mainly involve platelet aggregation inhibitors (PAIs) or anticoagulants. PAIs are mainly prescribed for primary or secondary prevention of arterial thrombosis, such as non-cardiogenic ischemic stroke [8], and for coronary and peripheral arterial disease (PAD) [9, 10]. Anticoagulants include three types: 1) heparins, 2) vitamin K antagonists (VKA), and 3) non-VKA oral anticoagulants (NOACs). The majority of patients with a life-limiting disease use anticoagulants for the prevention of thromboembolic events due to atrial fibrillation (AF) [11]. Other main reasons for using anticoagulants in the last phase of life are primary or secondary prevention and treatment (tertiary prevention) of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and prevention of thromboembolic events after heart valve replacement.

Most patients have been taking antithrombotics for a long period of time before their life expectancy becomes limited due to an illness. The number of patients still using antithrombotics at the end of life may vary depending on the population, setting and country. Of 16,896 patients with lung cancer who were admitted to a hospice, 9.2 % used an anticoagulant, of whom about 80 % used a VKA and the remaining 20 % a low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) [12]. In a retrospective study, 1141 patients who were admitted for acute care in a hospital were discharged to hospice care [11]. Of these patients, 64 % had a cardiovascular disease, and about 20 % suffered from cerebrovascular disease. Only 77 (6,7 %) patients had a prescription for antithrombotic therapy upon their discharge to hospice care. The main indications for antithrombotic use in this study were AF (41.6 %), history of stroke (31.2 %), deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) (11.7 %) or heart valve replacement (10.4 %). Various other studies have shown that up to half of all patients with an advanced illness and frail elderly patients continue to use antithrombotics in the last weeks of life [1,2,3,4]. A large cohort study in Sweden in older adults showed that antithrombotic use was similar (about 50 %) 12 months and one month before death. Most of these patients used a PAI (44 %), about 7 % a VKA and 2–5 % a LMWH [1]. About 20–30 % of patients in a hospice or frail elderly still use PAIs [5,6,7].

In the last phase of life, when treatment is primarily focused on optimizing patients’ quality of life, the use of antithrombotics should be reconsidered since the risk benefit ratio may change [13,14,15,16,17]. Clinically apparent VTE occurs in as many as 10 % of cancer patients [18], whereas almost 10 % of patients experience a clinically relevant bleeding at the end of life, with about one fifth of these bleedings contributing to death [15].

Comprehensive guidelines for (dis)continuation of antithrombotics in patients with a life-limiting disease are not available [19, 20]. The lack of evidence on outcomes of (dis)continuation of medication at the end of life and the complexity of clinical situations may lead to dilemmas in decision-making regarding antithrombotics. Moreover, insufficient awareness promotes continuation of potentially inappropriate medication in the last phase of life [21]. This may unnecessarily result in suboptimal quality of life and quality of death for patients with malignant and non-malignant life-limiting diseases. Thromboembolic as well as bleeding complications may lead to acute severe distressing situations, for patients, family and health care professionals.

In this paper, we report on a chart review study of the prescription of antithrombotics for patients with a life expectancy of less than three months staying at home, in a hospice or a hospital. The aim of this study was to gain more insight into management of antithrombotics in patients with a life-limiting disease and to conduct an in-depth analysis of the (dis)continuation of antithrombotics in patients in the last three months of life.

Methods

Design

We conducted a secondary analysis of a retrospective chart review within the MEDIcation management in the LAST phase of life (MEDILAST) project. MEDILAST is a multicenter mixed methods research project with the aim of understanding current medication use in the last phase of life. The project was carried out by Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen, and Amsterdam University Medical Center Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, all in the Netherlands. The study design, data collection and results of overall medication use in the last week of life have been described previously [22].

Data collection

We collected a convenience sample of medical records of patients who had died at home, in a hospice or in a hospital. We aimed to include 60 medical records in each region of influence of the participating centers (Rotterdam, Nijmegen and Amsterdam). In each region 20 medical records were drawn from the home, hospice and hospital setting. We asked physicians to select their two or three most recent cases of patients who had died expectedly from a chronic condition. For each region, we randomly selected a number of family physician practices and approached them by telephone. In each region, the hospice setting was represented by a high care hospice, where a palliative care physician is at all times available for consultation. For the hospital setting, we included records from patients who had died in an academic or peripheral hospital, at a cardiology, geriatrics, neurology, oncology or pulmonology ward.

Following acceptance to participate in the study, three physician researchers (second, third and fourth author) visited the clinical wards and practices to collect the data. A structured electronic form (MS Access 2013) was used to retrieve the information from the medical records. Demographics included age at the time of death, place of death and primary and comorbid diagnoses. Information about medication use in the last three months of life was registered, which included medication generic names, administration routes, doses and start and stop dates. The medical records were manually screened for information about the decision making on medication use. The indication for the antithrombotic was derived from clinical notes as well as primary and secondary diagnoses. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations for data collection from medical records [23]. All medication prescriptions of patients using antithrombotics were reviewed manually and of each patient using antithrombotics a case description was made including decision-making regarding the medication. Subsequently, case descriptions were selected by purposive sampling, with variation in setting, age, gender, medication, underlying disease and medical history and were rewritten as illustrative case vignettes.

The Medical Ethics Review Committee of the Amsterdam University Medical Center Vrije Universiteit approved the study protocol (ref. no. 2013/47). Approval in all other participating centers was obtained from the board of directors or relevant authority before data collection.

Data analysis

Medications were coded using the World Health Organization Center for Drug Statistics Methodology’s Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification at the level of therapeutic subgroup (second), pharmacological subgroup (third), medication chemical subgroup (fourth) and chemical substance (fifth) [24]. IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM Corporation, 2019) was used to obtain descriptive statistics.

Results

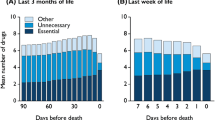

A total of 180 medical records were reviewed in this study. One patient died within 24 h of admission to a hospice and was not included in the analysis. In the last three months of life, 60% (n=108) of patients had used antithrombotics. Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients using antithrombotics per setting. Of all patients using antithrombotics 46.3 % were female; 33.3 % died at home, 21.3 % in a hospice and 45.4 % in a hospital. The period of time for which medication use was registered ranged from one day to three months (mean 43.8 days, median 24 days). In total, 157 antithrombotic prescriptions were registered (see Table 2). In 82 patients (75.9 %), antithrombotics were continued until the last week before death. Case vignettes of patients using antithrombotics are presented in Tables 3, 4 and 5.

Vitamin K antagonists

In total, 30 prescriptions of VKAs were registered in 29 patients, of whom 41.4 % died at home, 10.3 % in a hospice and 48.3 % in a hospital. Only one patient used phenprocoumon, all other prescriptions involved acenocoumarol (n = 29). In one patient acenocoumarol was stopped because of an intervention and restarted. The indications for the VKA varied from atrial fibrillation (Table 3, case 1 and 2), cardiac failure, cardiac valve disease, PE, DVT, to PAD (Table 3, case 3) and previous cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or transient ischemic attack (TIA) (Table 3, case 1). In total, 23 patients stopped using the VKA before death, of whom 17 patients less than one week before death (range 0–33 days, mean 5.2 days, median 2 days). In four patients bleeding complications were registered: painful hematoma in the flank (92 yrs, AF, TIA and urosepsis), fatal subdural hematoma (87 yrs, previous myocardial infarction, cardiac valve disease and renal insufficiency, combined with PAI), hematomas due to frequent falls (Table 3, case 2) and lung bleeding in lung cancer (Table 3, case 3). In some cases the VKA was stopped because of a prolonged INR (78 yrs, AF, cardiac failure, PAD and dialysis; 99 yrs, AF, cardiac failure and renal insufficiency). Other reasons for discontinuation that were mentioned were difficulty to swallow medication, drowsiness (Table 3, case 1), interaction with fluconazole, clinical deterioration, short life expectancy and patient’s request. In one patient suffering from an ileus the VKA was switched to therapeutic LMWH.

Heparins

In total, 60 prescriptions were registered in 51 patients, of whom 13.7 % died at home, 23.5 % in a hospice and 62.7 % in a hospital. Thirty-two patients received LMWH only in a prophylactic dose because of an acute medical condition or bedriddenness (Table 4, case 1). In three patients the prescribed heparin was changed to a different formulation. In two patients the dose was adjusted from a prophylactic dose to a therapeutic dose, because of newly diagnosed PE in one case and unknown condition in another case. In one patient with cardiac failure a heparin pump was discontinued, because of the decision to discontinue life-sustaining treatments, and switched to prophylactic LMWH. In several patients a heparin was started a few weeks before death (e.g. Table 4, case 1 and 2). Even in an unconscious or sedated patient the heparin was continued (Table 4, case 1, 2 and 3). A patient with colon carcinoma and previous PE received therapeutic dose LMWH until death, despite frequent nose bleeding. In total, 31 patients stopped using the heparins before death, of whom 21 patients less than one week before death (range 0–59 days, mean 5.5 days, median 1 day). Some specific reasons were mentioned for discontinuation. In two patients because of a bleeding (LMWH prophylaxis in laryngeal carcinoma and prophylaxis in a patient with an intracranial tumor) and once as family wanted unnecessary medication to be discontinued

Platelet aggregation inhibitors

In total, 66 prescriptions of platelet aggregation inhibitors were registered in 55 patients, of whom 36.4 % died at home, 18.2 % at a hospice and 45.5 % in a hospital. Two of these patients used two PAIs (i.e. acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel). Other patients used a PAI and LMWH (n = 11) or VKA (n = 5), or two PAIs and a LMWH (n = 3) or VKA (n = 2). In three patients a PAI was switched to a different formulation in the last weeks of life. A patient suffering from sepsis, and previous history CVA, PAD, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes and hypertension, used acetylsalicylic acid, clopidogrel and fondaparinux until start of palliative sedation. In total, 39 patients stopped using the PAI before death, of whom 29 patients less than one week before death (range 0–76 days, mean 5.9 days, median 1 day). In several patients the PAI was discontinued because of refusal by the patient, difficulty (Table 5, case 2) or discomfort to swallow medication. A 83-year old patient with a previous ischemic CVA and hypertension used acetylsalicylic acid and dipyridamole and died of a massive intracranial bleeding. In some patients the PAI was continued despite discontinuation of other oral preventive medications (Table 5, case 1). Table 5 case 3 presents a case vignette of a patient with lung cancer with cerebral metastases using a PAI because of intermittent claudication, in which the PAI is continued until death.

Discussion

In this chart review study we found that a large number of patients used antithrombotics in the last three months, weeks or days of their lives. PAIs and heparins were more frequently prescribed than VKA, and antithrombotic prescriptions were more frequent in patients who died in a hospital. The case vignettes reveal examples of what happens in clinical practice on the patient level and show that antithrombotics are continued until death, irrespective of (dis)continuation of other medications in the last weeks of life. Antithrombotics may be of questionable benefit due to changes in goals of care in the last phase of life and the benefit-harm balance of this medication.

In our study, we found a relatively high prevalence of antithrombotic use (60 %) compared to previous studies [1,2,3, 5]. We do not have a plausible explanation for this. As in the other studies, the antithrombotics in our study mainly involved PAIs. The second most frequently used antithrombotic in patients with a life-limiting disease is VKAs or LMHWs depending on the population studied [1, 4, 5, 12]. In our study a relatively high number of patients used LMWHs, with about half of the prescriptions concerning a prophylactic dose.

Dilemmas in decision-making

We hypothesize that physicians may be reluctant to discontinue antithrombotics due to complex clinical dilemmas. On the one hand, the medical assessment of potential benefits of (dis)continuing antithrombotics and minimizing the risk of adverse events is complicated and hampered by uncertainties. On the other hand, it is a challenge to discuss the use of antithrombotics with the patient and to reach a shared decision, taking into account benefits versus risks, patients’ quality of life and perceived medication burden. Studies into dilemmas in decision-making regarding antithrombotics in patients with a limited life expectancy, mostly concern anticoagulation in cancer patients and deprescribing of medication in frail elderly. Dilemmas in decision-making regarding antithrombotics in patients with a limited life expectancy reflected by the case vignettes and described in literature are multiple [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Examples of these dilemmas are: when to (dis)continue anticoagulants in patients with AF and cancer (Table 3, case 1), old age, frailty (Table 3, case 2) or risk of falls; when to (dis)continue PAIs in patients with cardiovascular disease combined with or without cancer (Table 5); when (not) to start or stop thromboprophylaxis (e.g. bedriddenness) (Table 4, case 1); when (not) to start or stop anticoagulants in cancer patients with symptomatic or incidental VTE (Table 4, case 2 and 3); how to balance the risk of bleeding versus PE in patients with lung carcinoma (Table 3, case 3); how to manage antithrombotics in patients with an increased risk of bleeding due to comorbidity (e.g. thrombocytopenia); which PAI or (dose of) anticoagulant is most appropriate.

Cancer associated thrombosis

Noble and colleagues especially contributed to this field with their studies into cancer associated thrombosis (CAT) and mention that according to guidelines indefinite anticoagulation should be considered for patients with cancer and VTE [33,34,35]. Particularly, stomach and pancreas carcinoma are associated with a very high risk of CAT, and lymphoma, lung, gynecologic, bladder, testicular and renal carcinoma with a high risk [36]. However, though the majority of CAT patients with metastatic disease remain anticoagulated up to or within days of death, it appears that anticoagulation in this situation confers a significant bleeding risk without additional benefit of preventing VTE symptoms [33]. The OncPal deprescribing guideline is the only guideline for deprescribing of medication in oncological patients, and merely addresses the use of aspirin with the advice to discontinue it in case of primary prevention [37].

(De)prescribing in elderly

Guidelines or tools for medication management in patients with a limited life expectancy due to non-malignant disease mainly involve those for elderly with advanced age, dementia or multimorbidity [38,39,40]. The Beers criteria and STOPP/START are some of the frequently used tools. The Beers criteria regarding antithrombotics advice to use aspirin for primary prevention with caution in adults above 70, prasugrel with caution above 75 years; to avoid oral short acting dipyridamole; and prescribe dabigatran and rivaroxaban for treatment of VTE or AF with caution in adults above 75 years; and avoid or reduce the dose of NOACs in the case of reduced renal function [41]. The STOPP/START give recommendations for adults above 65 years, mainly to avoid any antithrombotic in case of a significant bleeding risk; combine aspirin and clopidogrel only in selected cases; not to combine PAIs with VKA or NOACs; to discontinue VKA or NOACs after more than 6 respectively 12 months in patients without continuing provoking risk factors suffering a first DVT or PE [42]. Unfortunately, there is still a lack of standardization in assessment of medication appropriateness in patients with a limited life expectancy and a need for an approach that is specifically designed and validated for populations with a life-limiting illness [39].

Need for clinical guidance

In this chart review study, we found that discontinuation of antithrombotics seems to be done mainly in reaction to a bleeding, inability to swallow or patient’s request. In a previous study we found that there is substantial variation in physicians’ opinions regarding the use of anticoagulants in patients with a limited life expectancy and they lack evidence about the risks and benefits of stopping anticoagulants in decision-making [43]. Which decision physicians eventually made seemed largely dependent on the choice of the patient [43]. Physicians need more evidence-based guidance to proactively discuss the use of antithrombotics and direction to come to a decision consistent with the patient’s goals and preferences. Patients with a life-limiting disease often prefer to reduce the number of medications they have to take, but they have concerns about the negative consequences or uncertainty of stopping the medication [44], risk of bleeding or thromboembolic complications [45]. Thus, clinical guidance may facilitate more rational and patient centered decisions. Therefore, we propose that a first step towards clinical guidance could be considered in practice to guide medical advice for antithrombotics and shared decision-making in patients with a life expectancy of less than three months (Supplement, with Figs. 1 and 2).

Limitations

Our study involved a secondary analysis of data from a retrospective chart review study. Results might be influenced by selection bias and discrepancy between the registered prescriptions and actual use. Not in all cases the decision-making process was clear due to insufficient description in the clinical notes. Whereas the indication of antithrombotic use is not explicitly recorded in medical records, in most cases it was derived from clinical notes as well as patients’ primary and secondary diagnoses. Further, possibly relevant comorbid conditions, like renal function and coagulation disorders, were often not specifically registered with laboratory results, especially in patients in hospices or at home. Our sample of patients is relatively out of date concerning the use of NOACs. None of the patients used a NOAC. Specific considerations regarding NOACs were not represented, such as the relative ease in use or inferior efficacy in certain patient populations. However, the dilemmas regarding (dis)continuation are considered to be comparable to VKAs and therapeutic dose LMWHs. It was not the scope of this study to elaborate on the choice of anticoagulant for therapeutic use. Guidelines for the management of AF [46], VTE [47] and CAT [48] do give recommendations on the choice of anticoagulant, and many studies focus on this in complex patients with CAT [29, 49], AF in cancer patients [50] and in elderly patients [41, 51].

Conclusions

A large number of patients with a life limiting disease still use antithrombotics in the last three months and even days of their lives. PAIs and heparins were more frequently prescribed than VKA, and antithrombotic prescriptions were more frequent in hospitalized patients. Dilemmas in decision-making regarding antithrombotics in patients with a limited life expectancy are reflected by case vignettes, and it seems that decision-making regarding antithrombotics is mainly a reactive process. The impact of possible thromboembolic and bleeding complications on quality of life and quality of death demand for a proactive decision-making regarding antithrombotics. Clinical guidance may support physicians to proactively give medical advice regarding (dis)continuation of antithrombotics and consecutively have a shared-decision making discussion with the patient.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy of respondents, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PAI:

-

Platelet Aggregation Inhibitor

- PAD:

-

Peripheral Arterial Disease

- VKA:

-

Vitamin K antagonist

- NOAC:

-

Non-VKA Oral AntiCoagulant

- AF:

-

Atrial Fibrillation

- VTE:

-

Venous ThromboEmbolism

- LMWH:

-

Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin

- DVT:

-

Deep Venous Thrombosis

- PE:

-

Pulmonary Embolism

- MEDILAST:

-

MEDIcation management in the LAST phase of life

- ATC:

-

Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical

- CVA:

-

CerebroVascular Accident

- TIA:

-

Transient Ischemic Attack

- (N)IDDM:

-

(Non) Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus

- COPD:

-

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- CAT:

-

Cancer Associated Thrombosis

References

Morin L, Vetrano DL, Rizzuto D, Calderon-Larranaga A, Fastbom J, Johnell K. Choosing Wisely? Measuring the Burden of Medications in Older Adults near the End of Life: Nationwide, Longitudinal Cohort Study. Am J Med. 2017;130(8):927–36 e9.

Pasina L, Recchia A, Agosti P, Nobili A, Rizzi B. Prevalence of Preventive and Symptomatic Drug Treatments in Hospice Care: An Italian Observational Study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(3):216–21.

Pasina L, Recchia A, Nobili A, Rizzi B. Inappropriate medications among end-of-life patients living at home: an Italian observational study. European geriatric medicine. 2020;11(3):505–10.

Heppenstall CP, Broad JB, Boyd M, Hikaka J, Zhang X, Kennedy J, et al. Medication use and potentially inappropriate medications in those with limited prognosis living in residential aged care. Australas J Ageing. 2016;35(2):E18-24.

Sera L, McPherson ML, Holmes HM. Commonly prescribed medications in a population of hospice patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(2):126–31.

McLean S, Sheehy-Skeffington B, O’Leary N, O’Gorman A. Pharmacological management of co-morbid conditions at the end of life: is less more? Ir J Med Sci. 2013;182(1):107–12.

Onder G, Liperoti R, Foebel A, Fialova D, Topinkova E, van der Roest HG, et al. Polypharmacy and mortality among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment: results from the SHELTER study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(6):450 e7-12.

Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, Bravata DM, Chimowitz MI, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2160–236.

Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, Collet JP, Costa F, Jeppsson A, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur J Cardio-thoracic Surg. 2018;53(1):34–78.

Kithcart AP, Beckman JA, ACC/AHA Versus ESC. Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Peripheral Artery Disease: JACC Guideline Comparison. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(22):2789–801.

Kowalewska CA, Noble BN, Fromme EK, McPherson ML, Grace KN, Furuno JP. Prevalence and Clinical Intentions of Antithrombotic Therapy on Discharge to Hospice Care. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(11):1225–30.

Holmes HM, Bain KT, Zalpour A, Luo R, Bruera E, Goodwin JS. Predictors of anticoagulation in hospice patients with lung cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(20):4817–24.

van Nordennen RT, Lavrijsen JC, Heesterbeek MJ, Bor H, Vissers KC, Koopmans RT. Changes in Prescribed Drugs Between Admission and the End of Life in Patients Admitted to Palliative Care Facilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(6):514–8.

Gomez-Batiste X, Martinez-Munoz M, Blay C, Amblas J, Vila L, Costa X, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of patients with advanced chronic conditions in need of palliative care in the general population: a cross-sectional study. Palliat Med. 2014;28(4):302–11.

Tardy B, Picard S, Guirimand F, Chapelle C, Danel Delerue M, Celarier T, et al. Bleeding risk of terminally ill patients hospitalized in palliative care units: the RHESO study. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis: JTH. 2017;15(3):420–8.

Arahata M, Asakura H. Antithrombotic therapies for elderly patients: handling problems originating from their comorbidities. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:1675–90.

Ferreira C, Providencia R, Ferreira MJ, Goncalves LM. Atrial Fibrillation and Non-cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review. Arquivos brasileiros de cardiologia. 2015;105(5):519–26.

Bauer KA. Risk and prevention of venous thromboembolism in adults with cancer. In: Leung LLK, Tirnauer JS, editors. UpToDate. Waltham: UpToDate Inc.; Accessed 20 Apr 2020.

Spiess JL. Can I stop the warfarin? A review of the risks and benefits of discontinuing anticoagulation. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(1):83–7.

Carrier M, Khorana AA, Moretto P, Le Gal G, Karp R, Zwicker JI. Lack of evidence to support thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients with cancer. The American journal of medicine. 2014;127(1):82–6 e1.

Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C, Scott I. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006544.

Arevalo JJ, Geijteman ECT, Huisman BAA, Dees MK, Zuurmond WWA, van Zuylen L, et al. Medication Use in the Last Days of Life in Hospital, Hospice, and Home Settings in the Netherlands. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(2):149–55.

Jansen AC, van Aalst-Cohen ES, Hutten BA, Buller HR, Kastelein JJ, Prins MH. Guidelines were developed for data collection from medical records for use in retrospective analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(3):269–74.

WHO. Introduction to Drug Utilization Research. Oslo: World Health Organization; 2003.

Voigtlaender M, Langer F. Management of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism - a case-based practical approach. VASA Zeitschrift fur Gefasskrankheiten. 2018;47(2):77–89.

Noble S. The challenges of managing cancer related venous thromboembolism in the palliative care setting. Postgraduate medical journal. 2007;83(985):671–4.

Drenth-van Maanen AC, van Marum RJ, Knol W, van der Linden CM, Jansen PA. Prescribing optimization method for improving prescribing in elderly patients receiving polypharmacy: results of application to case histories by general practitioners. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(8):687–701.

Johnson MJ, Sheard L, Maraveyas A, Noble S, Prout H, Watt I, et al. Diagnosis and management of people with venous thromboembolism and advanced cancer: how do doctors decide? A qualitative study. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2012;12:75.

Al-Samkari H, Connors JM. Managing the competing risks of thrombosis, bleeding, and anticoagulation in patients with malignancy. Hematology American Society of Hematology Education Program. 2019;2019(1):71–9.

Disalvo D, Luckett T, Agar M, Bennett A, Davidson PM. Systems to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing in people with advanced dementia: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:114.

Lainscak M, Dagres N, Filippatos GS, Anker SD, Kremastinos DT. Atrial fibrillation in chronic non-cardiac disease: where do we stand? International journal of cardiology. 2008;128(3):311–5.

Sheard L, Prout H, Dowding D, Noble S, Watt I, Maraveyas A, et al. The ethical decisions UK doctors make regarding advanced cancer patients at the end of life–the perceived (in) appropriateness of anticoagulation for venous thromboembolism: a qualitative study. BMC medical ethics. 2012;13:22.

Noble S, Banerjee S, Pease NJ. Management of venous thromboembolism in far-advanced cancer: current practice. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2019.

Noble S. Venous thromboembolism and palliative care. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19(4):315–8.

Chin-Yee N, Tanuseputro P, Carrier M, Noble S. Thromboembolic disease in palliative and end-of-life care: A narrative review. Thrombosis research. 2019;175:84–9.

Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, Lyman GH, Francis CW. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood. 2008;111(10):4902–7.

Lindsay J, Dooley M, Martin J, Fay M, Kearney A, Khatun M, et al. The development and evaluation of an oncological palliative care deprescribing guideline: the ‘OncPal deprescribing guideline’. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(1):71–8.

Onder G, Landi F, Fusco D, Corsonello A, Tosato M, Battaglia M, et al. Recommendations to prescribe in complex older adults: results of the CRIteria to assess appropriate Medication use among Elderly complex patients (CRIME) project. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(1):33–45.

Todd A, Husband A, Andrew I, Pearson SA, Lindsey L, Holmes H. Inappropriate prescribing of preventative medication in patients with life-limiting illness: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(2):113–21.

Bulloch MN, Olin JL. Instruments for evaluating medication use and prescribing in older adults. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2014;54(5):530-7.

By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert P. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674–94.

O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213–8.

Huisman BAA, Geijteman ECT, Kolf N, Dees MK, van Zuylen L, Szadek KM, et al. Physicians' Opinions on Anticoagulant Therapy in Patients with a Limited Life Expectancy. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. 2021 May 10. Epub ahead of print.

Geijteman EC, Dees MK, Tempelman MM, Huisman BA, Arevalo JJ, Perez RS, et al. Understanding the Continuation of Potentially Inappropriate Medications at the End of Life: Perspectives from Individuals and Their Relatives and Physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2602–4.

Benelhaj NB, Hutchinson A, Maraveyas AM, Seymour JD, Ilyas MW, Johnson MJ. Cancer patients’ experiences of living with venous thromboembolism: A systematic review and qualitative thematic synthesis. Palliat Med. 2018;32(5):1010–20.

Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2020.

Lip GYH, Hull RD. Rationale and indications for indefinite anticoagulation in patients with venous thromboembolism. In: Mandel J, Leung LLK, editors. UpToDate. Waltham: UpToDate Inc.; Accessed 7 Oct 2020.

Key NS, Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Bohlke K, Lee AYY, Arcelus JI, et al. Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis and Treatment in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2020;38(5):496–520.

Song AB, Rosovsky RP, Connors JM, Al-Samkari H. Direct oral anticoagulants for treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients. Vascular health and risk management. 2019;15:175–86.

Delluc A, Wang TF, Yap ES, Ay C, Schaefer J, Carrier M, et al. Anticoagulation of cancer patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation receiving chemotherapy: Guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis: JTH. 2019;17(8):1247–52.

Granziera S, Cohen AT, Nante G, Manzato E, Sergi G. Thromboembolic prevention in frail elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: a practical algorithm. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(5):358–64.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for all physicians who participated in this study. We would like to thank our graphic specialist Camilo García Villamil (www.polari.co) for his input on the design of the figures.

Funding

ZonMw funded the study under grant number 80-82100-98-210. Funder role: none, regarding study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data and writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EG, MD, LZ and AH wrote the research proposal for the primary study. EG, JA and MD collected the data. BH, EG, JA, AH, KS and MS were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data. Furthermore, all authors were involved in the critical appraisal of the manuscript and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Radboud University Medical Centre (NL44030.091.13). The participating institutions approved the research. All participants gave written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Huisman, B.A., Geijteman, E.C., Arevalo, J.J. et al. Use of antithrombotics at the end of life: an in-depth chart review study. BMC Palliat Care 20, 110 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00786-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00786-3