Abstract

Background

Children with disabilities experience poorer oral health and frequently have complex needs. The accessibility of oral health care services for children with disabilities is crucial for promoting oral health and overall well-being. This study aimed to systematically review the literature to identify the barriers and facilitators to oral health care services for children with disabilities, and to propose priority research areas for the planning and provision of dental services to meet their needs.

Methods

This was a mixed methods systematic review. Multiple databases searched included MEDLINE, Scopus, PsycINFO, EMBASE, and CINAHL. The search strategy included Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms related to children, disabilities, and access to oral health. Eligibility criteria focused on studies about children with disabilities, discussing the accessibility of oral health care.

Results

Using Levesque’s framework for access identified barriers such as professional unwillingness, fear of the dentist, cost of treatment, and inadequate dental facilities. Facilitators of access offered insight into strategies for improving access to oral health care for children with disabilities.

Conclusion

There is a positive benefit to using Levesque’s framework of access or other established frameworks to carry out research on oral healthcare access, or implementations of dental public health interventions in order to identify gaps, enhance awareness and promote better oral health practices. The evidence suggests that including people with disabilities in co-developing service provision improves accessibility, alongside using tailored approaches and interventions which promote understanding of the importance of dental care and increases awareness for professionals, caregivers and children with disabilities.

Trial registration

Protocol has been registered online on the PROSPERO database with an ID CRD42023433172 on June 9, 2023.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

The United Nations Children’s International Emergency Fund (UNICEF) estimates the number of children with disabilities is nearly 240 million [1]. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), disability is a comprehensive concept that encompasses impairments, limitations in activities, and restrictions in participation. It is not solely a biological or social construct, but rather emerges from the interplay between health conditions and various environmental and personal factors [2]. Children with disabilities are at higher risk of poorer health than the general population and the academic evidence highlights the existence of health disparities between children with and without disabilities [3]. Children with disabilities also experience poorer oral health, with problems ranging from tooth decay and gingivitis to severe periodontal disease [4]. One longitudinal clinical study has identified that oral health inequity tends to begin in childhood, perpetuating and increasing across the lifecourse, with access to oral health care a key factor associated with better oral health [5]. Compared to their non-disabled peers, children with disabilities frequently possess complex oral health care needs [6,7,8,9,10]. For example, underlying health conditions may exert an effect on oral health [6, 7], sensory and motor impairments may affect their ability to attend routine dental care [8, 9] and physical impairments can make oral health care practices, such as toothbrushing, challenging [10].

Children with and without disabilities need support to access healthcare services, but this can be variable and is dependent on the skills and abilities of caregivers to distinguish between the type and extent of support needed [11, 12]. Limited access to oral health care services links to poor oral health outcomes, which may lead to inequalities in oral health for children with disabilities [13, 14]. Access, however, is complex, it does not merely mean physically entering a service, it has numerous constructs and potentially modifiable factors such as negative attitudes of professionals, a lack of service provision, or poor geographical distribution of services, amongst others. Then there are fixed factors such as a lack of socio-economic resources in the family, or factors relating to impairment, all of which create barriers to access.

Over the past four decades, various frameworks have been developed to help understand healthcare access dynamics [15,16,17,18,19]. One recent and comprehensive framework is Levesque’s Conceptual Framework for Healthcare Access (Fig. 1), published in 2013 after an extensive review of existing literature on healthcare access [20]. This framework offers a multidimensional perspective on healthcare access within the context of health systems, encompassing approachability, acceptability, availability/accommodation, affordability, and appropriateness. It takes into account socioeconomic determinants and incorporates five corresponding abilities of individuals and populations: to perceive, to seek, to reach, to pay, and to engage, in healthcare access [20]. Unlike approaches that solely focus on health system failures, Levesque’s framework allows researchers to explore barriers to access resulting from individuals’ abilities to perceive, seek, reach, pay, or engage with healthcare. Access, as defined in this framework, encompasses the opportunity to identify, seek, reach, obtain, or use healthcare services while meeting individual needs access [20].

Existing systematic reviews highlights main barriers to dental services for individuals with disabilities, including professional unwillingness to care for their teeth, fear of the dentist, cost of treatment, lack of adaptation of access routes to dental offices or clinics and inadequate health care or dental facilities [21, 22]. The work by da Rosa and colleagues [22] and Krishnan and colleagues [21] only provides a brief overview because one is restricted to including only cross-sectional studies, and the other refers to barriers faced by caregivers alone. Neither represents a comprehensive analysis of the literature using a broader theoretical framework. Moreover, these reviews [21, 22] failed to discuss the facilitators of access to oral health services for people with disabilities. Facilitators of access may resolve barriers to accessing dental services. In contrast, one qualitative study discusses facilitators and barriers, which cross-sectional studies fail to, because the design does not infer cause and effect relationship [23]. However, this small-scale qualitative study is about adults with disabilities in the UK and not generalizable to other populations. Children with disabilities need support to access dental care, therefore, it is important to identify factors that promote or inhibit access and thereby provide a template of how to increase positive oral health outcomes and attempt to reduce inequalities.

Using Levesque’s Conceptual Framework for Healthcare Access as an a priori framework, this study aimed to (1) systematically review the literature to identify the barriers and facilitators to oral health care services for children with disabilities, and (2) to propose priority research areas for the planning and provision of dental services to meet their needs. The identification of barriers and facilitators to dental care services among children with disabilities could provide guidance for the development of targeted interventions to improve access to oral health care and overall health.

Methods

This study is a mixed method systematic review of the evidence on access to oral health care services for children with disabilities, up to 31st May 2024. Using Participant, Intervention, Comparator and Outcome (PICO) to develop the question, the overarching research question guiding this systematic review was ‘What interventions or designs enable the accessibility of oral health care services for children with disabilities and their parents/carers?’ Other questions are ‘What are the barriers to accessibility of oral health care services for children with disabilities and their parents/carers?’ ‘What increases utilization of oral health care services for children with disabilities and their parents/carers?’

The study follows the updated JBI methodological guidance for conducting a mixed methods systematic review [24].

Registration of the protocol and PRISMA guidelines

The review adhered to the guidelines provided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [25]. Prior to conducting the systematic review, the authors developed a review protocol and registered it with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews PROSPERO on June 9, 2023, under the registration number (CRD42023433172).

Data sources and searches

The search strategy for this systematic review involved searching multiple databases, including MEDLINE, Scopus, PsycINFO, EMBASE, CINAHL and Google Scholar to ensure a comprehensive coverage of relevant studies beyond the databases. Backward or chain searching of references, involves identifying and examining the references or works and enables learning around the development of a topic, whilst identifying experts in the area. Forward searching of references within retrieved records cited in an article after its publication enables finding new theoretical developments in the area and consideration of any other methodologies employed. Second generation forward searching enables the researcher to search for inconsistencies. This process of backward and forward searching of references identified any additional relevant literature for inclusion. To ensure accuracy in the research terminology used, librarians from The University of Sheffield and Manchester University were consulted. Additional file 1. illustrates the complete list of MeSH search terms and the full electronic search strategy.

Eligibility criteria

Population

The studies included in the review included children with disabilities aged 18 years or below. In cases where studies included both adults and children or adolescents, they were considered eligible for inclusion if at least 75% of the participants were children or adolescents, or if separate outcome data were available for this subgroup. This study uses People First language and employs the term children with disabilities, rather than disabled children, although it acknowledges that using the term disabled children implies that society creates barriers because it employs language favored by the social model of disability [26].

Interventions

Studies discussing access or mentioning dimensions of access to oral health care for children with disabilities were included. Studies of reasonable adjustments and improved access to oral health care for children with disabilities were also included. Oral health studies that solely focused on a particular condition (e.g., Down’s syndrome) or focused solely on the diagnosed oral health condition (e.g., caries or periodontal disease) without any mention of access were excluded. All oral healthcare settings, including dental clinics, hospitals, community health centers, or specialized dental facilities for children with disabilities, were included.

Comparators

Studies with any comparator or no comparator were included. Comparators included intervention or care as usual, as well as studies utilizing alternative approaches for access to oral health care.

Outcomes

The primary outcome assessed in the study was access to oral health care for children with disabilities. If otherwise eligible, for studies that did not report a relevant outcome, attempts were made to contact the authors to determine the outcome. In cases where it was not possible to determine this, the study was listed but the data not fully extracted or included. There is a difference between access to services and effectiveness [27]. Therefore, papers reporting the ability to physically access, use a service, and/or the standard of service provision were included. Additionally, studies reporting the effectiveness of measures or interventions designed to improve access to the relevant services were reviewed.

Levesque et al.’s model of access [20] was used as an a priori framework to code how each study measured dimensions of accessibility and corresponding abilities.

Study selection

The study included the following research designs: randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled studies, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, and process evaluations. Mixed method studies and qualitative studies were also included. Systematic and scoping reviews were used to identify primary studies but were not directly included. Studies without primary data, case reports, government reports, guidelines, editorials, commentaries, opinion pieces and conference abstracts, were excluded. Publications in English or Arabic languages, including Arabic due to the Arabic-speaking first and second authors, were included. No countries were excluded from the study. No date restrictions were applied in the search strategy, ensuring a comprehensive inclusion of relevant studies regardless of their publication date. The search was completed up to 31st May 2024.

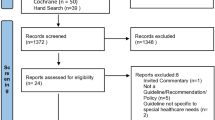

Inclusion screening

The articles resulting from the search were exported to an Endnote library [28] and duplicates removed. To ensure consistency, three reviewers (MA, AJ and JO) screened an initial 100 references. Any queries or uncertainties were resolved through discussion. Two reviewers (MA, AJ) then independently assessed the evidence for inclusion using the eligibility criteria at both the title/abstract and full-text screening stages. Disagreements were addressed through discussion and consensus. In cases where consensus was difficult to reach, a third independent researcher (JO) was involved. Studies that did not meet the eligibility criteria during the full-text screening stage were excluded, and reasons for exclusion were recorded (See Fig. 2).

Extraction of data

Data were tabulated in an Excel sheet, which included author and date, study design, country, sample size, type of disability, outcomes, and barriers and facilitators to access (See Table 1).

Two researchers (MA, AJ) utilized Levesque’s five dimensions of accessibility and abilities of persons to interact with the dimensions of accessibility. The table was piloted for 10% of the studies and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion before continuing. A third member of the review team (JO) resolved conflicts of agreement. Table 2 provides detailed analysis of the dimensions of accessibility and ability to interact with the dimensions.

Data synthesis and analysis

This mixed methods systematic review uses questions focusing on different aspects of the same phenomenon. Therefore, the synthesis took a convergent segregated approach, which consisted of conducting separate and independent quantitative and qualitative syntheses but using thematic analysis for both [24]. Both syntheses employed deductive thematic analysis based on the predefined themes from Levesque et al.’s model of access [20]. This approach synthesized findings from both qualitative and quantitative studies, offering a comprehensive understanding of access to oral health care for children with disabilities.

Quality and risk of bias assessment strategy

Given the variety of research designs included in this review, the quality of the studies was assessed using the Quality Appraisal for Diverse Studies (QuADS) [29], and risk of bias was evaluated using appropriate tools for each study design (AXIS Tool for Cross-Sectional Design, and Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools for both qualitative and case-control studies) [30,31,32].

QuADS assesses various important aspects of the studies, such as the underlying theory, defined objectives, appropriateness and rigor of the design, data collection methods, and analytical methods. It consists of 13 evaluative indicators, each rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (complete), allowing researchers to determine the extent to which each criterion is met. To ensure consistency, two reviewers (MA, AJ) conducted an initial pilot on 10% of the sample, resolving discrepancies through discussion or with a third reviewer (JO). Table 3 provides detailed scoring of the included studies.

Included studies were also critically appraised by two independent reviewers (MW and AJ) for risk of bias, using tools appropriate for each research design. Cross-sectional studies were evaluated with the “Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS)” [30] Table 4. The standardized Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklists were used for qualitative research [32] Table 5, and for case-control studies [31] Table 6. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

Results

The PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 2) illustrates the search results. After screening and applying the eligibility criteria, a total of 36 studies were included in the review.

Study characteristics

The studies incorporated a range of research designs. The majority of these studies (29 out of 36) adopted a cross-sectional study design, representing 80 % of the total papers. The next most common types of studies were qualitative studies, accounting for 11 % of the included papers, followed by case-control comparative studies (2 studies, 6%), and finally, one Mixed Method study (3%). (See Table 1).

The studies included 17 different countries (See Fig. 3). Among the countries represented in the included studies, the United States (USA) emerged as the most prominent location, contributing 10 studies. These studies encompassed a wide range of sample sizes, varying from 10 participants [33] to a significantly larger cohort of 12,539 participants [34].

The studies mentioned a diverse array of disabilities, such as Cerebral Palsy (CP), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Down Syndrome (DS), Intellectual and/or Developmental Disabilities (IDD), and Physical Disabilities. This broad scope allowed for a comprehensive exploration of the challenges and experiences faced by individuals living with different abilities.

Facilitators and barriers of access to oral health care for children with disabilities

The review identified factors that either facilitated or hindered access to oral healthcare for children with disabilities. These findings were categorized according to Levesque’s healthcare access framework, which organizes them based on dimensions and abilities. Table 1 presents a concise overview of the barriers and facilitators investigated in the included studies, and Table 2 provides a summary of the dimensions and abilities assessed within Levesque’s proposed framework. Included studies addressed barriers, but eight of them did not mention facilitators.

Dimensions of access

Approachability

The term “approachability” describes a provider’s characteristics that make it possible for people to know they exist and are reachable. This systematic review includes findings from seven studies that highlight both facilitators and barriers related to approachability. Dental outreach programs are identified as effective facilitators for enhancing approachability [33]. Conversely, the barriers to approachability include a lack of information about dentists competent to treat individuals with disabilities, as well as limited oral health awareness and knowledge of available services [35,36,37,38,39,40]. These barriers significantly hindered individuals’ access to and utilization of dental care services, thereby impacting approachability.

Acceptability

Nine of the included studies [33, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] align with the “acceptability” dimension as defined by Levesque et al.’s conceptual framework [20]. These studies considered the influence of cultural and societal factors on individuals’ acceptance of specific aspects of dental care access.

The findings from these studies suggest that societal discrimination against individuals with disabilities, characterized by negative attitudes and discriminatory practices, significantly hindered their ability to access dental care [33, 40]. Some studies cited the presence of male caregivers and the existence of activity limitations associated with profound autism, as factors involved in barriers for individuals seeking dental care [42]. Moreover, individuals with complex medical conditions or more urgent healthcare needs may face difficulties in accessing dental care, leading to reduced acceptability of services [43]. The Acceptability domain failed to identify any facilitators.

Availability/ accommodation

Within the scope of this systematic review, 26 out of the 36 studies included in the analysis contributed insights related to the “availability/accommodation” dimension, specifically addressing barriers and facilitators associated with dental care access [14, 33, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. Barriers linked to availability included the proximity of parking at dental clinics, challenges related to transportation and geographical distance from dental clinics. Other barriers included the absence of reasonable adjustments for accessing dental surgeries, difficulties in locating dentists willing to treat children with specific medical conditions, a shortage of dentists experienced in treating children with intellectual disabilities and prolonged waiting times for appointments or in waiting rooms.

Facilitators enhancing availability included the presence of diverse dental services providing needed care for individuals with disabilities [45, 58, 59], dentists demonstrating willingness to treat children [57], treatment availability, accessibility, and improved facilities in dental clinics.

Affordability

The issue of affordability appeared in twenty-two of the included studies [14, 33, 35, 37,38,39,40,41, 43, 44, 46, 47, 49, 50, 53, 57, 58, 60,61,62,63,64]. One of the most prevalent barriers hindering children with disabilities from accessing dental care is the prohibitively high cost of dental treatment, compounded by financial constraints and ineligibility for healthcare insurance [64]. However, reducing the cost of dental treatment can significantly enhance affordability and accessibility for children [33]. Consequentially, improving access to free dental care services has the potential to increase utilization rates among children with disabilities [33]. Another valuable facilitator is insurance coverage, for those who can afford it, which further enables access to dental care [35, 37].

Appropriateness

Barriers to dental care access for children with disabilities encompass multiple factors. These include the lack of family support [33]. Negative past experiences with dental services can create anxiety and reluctance [33, 59]. A shortage of behavior management skills among general practitioners [36], discomfort experienced by children during dental procedures [37, 64], and the reluctance of some dentists to treat children with disabilities can all affect the appropriateness of care [38, 39, 50, 59]. Furthermore, communication challenges [50] and the limited training and awareness of dental professionals about sensory issues in conjunction with the unique traits of children with disabilities can all hinder appropriate care [55].

Alternatively, facilitators contributing to the appropriateness of dental care access for children with disabilities include the presence of dental staff with positive attitudes [33] and interaction between the medical and dental systems through integrated care [61]. Parental positive attitudes and increased awareness of oral health encourages regular dental care, which enhances appropriateness [38, 43]. Real-time communication tools [51], coping strategies, and immersive empathy from the oral health team alleviates anxiety and ensures the acceptance of dental treatment [55]. Moreover, tailored communication, preparation, and support [55], along with the expertise of dental professionals who are trained to work with children with special health care needs [59], all play significant roles in improving the appropriateness of dental care for children with disabilities.

Abilities related to access

Several specific abilities relate to accessing oral healthcare. These include perceive, seek, reach, pay, and engage. Ability to perceive focuses on individuals’ awareness and understanding of available healthcare services. Ability to seek focuses on individuals’ initiative to look for oral healthcare services. Ability to reach refers to the geographical accessibility of oral healthcare facilities. Ability to pay refers to the financial ability to afford oral healthcare services. Ability to engage refers to individuals’ involvement and participation in their own oral healthcare.

Ability to perceive

Twenty-three studies discuss the ability to perceive the importance of dental care [14, 33, 36,37,38,39,40, 42,43,44, 47, 48, 53,54,55,56,57, 59, 60, 62,63,64,65,66]. Barriers include a lack of dental awareness among parents regarding oral health and availability of services [40, 56, 57, 60]. Often, there is little to no awareness of the importance of regular dental visits, contributing to limited perceptions of the necessity of ongoing dental care [60]. Some caregivers hold the belief that dental care is only essential for specific issues, such as swelling, cracked teeth with pain, or mobile teeth, providing evidence of a restricted understanding of the importance of regular dental visits [62]. Caregivers frequently perceive their child’s inability to cooperate with dental treatments [37, 47, 56]. They often express concerns about perceived behavioral challenges [14, 33, 37, 65]. The perception that children are too young for dental appointments [53] alongside the fear and anxiety children experience regarding dental care [14, 63], also present substantial barriers. Parental anxiety [63] and oral healthcare may have a lower priority compared to other healthcare needs for their child [14] and contribute to the challenges. Barriers related to children themselves including a lack of complaints expressed by children [54], children may face difficulties in recognizing dental pain and staff encounter challenges in facilitating communication [37]. These barriers collectively emphasize the need for the provision of tailored approaches and interventions to improve the perception of the importance of dental care among both caregivers and children with disabilities. Facilitators for enhancing the perception of the need for oral health care encompass various factors. Research suggests that the association between general health issues and parental health behaviors contributes to the recognition of dental care needs [37, 40, 43, 58, 65]. For example, children with Down Syndrome (DS) are more likely to seek dental care if they are also receiving speech therapy and ophthalmology services, illustrating a connection between overall health concerns and dental care [36]. Knowledge of oral health, active participation in oral healthcare programs [42] and caregiver education [44, 57, 63,64,65,66] also serve as facilitators. Providing parents with coping strategies and techniques tailored to autistic children [39] improves access to dental care, contributing to the ability to perceive the need for dental care.

Ability to seek

The ability to seek healthcare is influenced by various factors that impact individuals’ autonomy and choice to seek care. Barriers identified in the studies include difficulties and discomfort experienced by children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) during dental procedures [37], negative experiences with healthcare professionals [41], limited access to routine oral care among children belonging to ethnic minorities [49], perceived child IQ and behavioral issues [65]. These barriers hinder the ability to seek healthcare, resulting in disparities in accessing appropriate care.

On the other hand, facilitators identified include children’s age and parents’ educational attainment [63]. Older children may possess a better understanding and ability to express their healthcare needs, which facilitates their ability to seek care. Higher levels of education appear to facilitate parent acquisition of knowledge about healthcare options, enabling them to make informed decisions and actively seek necessary care for their children [63, 64].

Ability to reach

“Ability to Reach,” in 17 included studies, identify barriers primarily focusing on personal mobility and transportation availability, affecting individuals’ ability to physically reach healthcare providers [14, 33, 35, 37, 39, 40, 42, 44, 47, 50, 53, 56,57,58, 62,63,64]. These barriers encompass issues such as proximity of parking at clinics [33], lack of transportation [35, 50], difficulties in transportation [37, 47, 53, 62, 64], long travel distances, waiting times, challenges related to wheelchair access [40], limited access due to the scarcity of nearby dentists, insufficient time for visits, high travel costs, and time-consuming appointments. No studies mentioned facilitators of access.

Ability to pay

Fifteen studies explore barriers and facilitators related to the dimension of “ability to pay”, for dental care access for children with disabilities [33,34,35, 40, 41, 44, 48, 52, 53, 56, 57, 61, 62, 66, 67]. Barriers related to financial constraints, low income [34, 40, 56, 62], and a lack of insurance coverage [41, 48, 53, 67]. Facilitators within this domain were private insurance coverage, free treatment options [33], and insurance programs designed to provide dental care for vulnerable populations [35, 48, 67].

Ability to engage

Twenty-five studies discuss the ability to engage [33, 36,37,38, 40, 42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54, 56,57,58,59, 64,65,66], identifying numerous barriers to engaging children with disabilities in dental care. These obstacles range from children’s hesitance towards dental treatment [45] to difficulties experienced by children with ASD during dental procedures [37] and their perceived lack of cooperation during dental care [47]. Challenging behaviors, emerged from the fear of the dentist [52], which further compounds barriers. The anxiety of dental staff and concerns about uncooperative behavior or fear-related issues also hinder engagement [38]. Effective communication has been identified as a pivotal facilitator for dental care utilization [57]. Some studies suggest that having a milder degree of intellectual disability as a facilitator of access [50], suggesting that children with less severe intellectual disabilities may find it easier to engage with dental care compared to those with more significant communication impairments. Alternatively, dental staff may find it easier to communicate. It also suggests that dental professionals lack effective communication skills. These multifaceted barriers underscore the need for tailored strategies to enhance engagement among children with disabilities in accessing dental care.

Quality and risk of bias assessment

All included papers in this systematic review were rated for quality using the QuADS criteria [29]. (See Table 3). These revealed a mixed picture regarding the methodological rigor of the studies. Scores ranged from 36 to 85%, indicating varying levels of quality. While some studies demonstrated explicit theoretical or conceptual frameworks, clear descriptions of the research setting, and appropriate sampling methods, others lacked these crucial elements. The choice and justification of data collection tools and analytic methods varied, with some studies offering detailed justification and explanation, whilst others offered rudimentary accounts. Furthermore, few studies actively engaged stakeholders in the research design [14, 33, 52], for example, in one study stakeholders were actively involved [33], they formed an expert review committee and conducted pilot interviews with five caregivers to gather feedback on the clarity and language of the interview guide. The collaborative efforts resulted in a refined and validated Malay version of the guide, evidencing the active role of stakeholders in shaping the research design and ensuring methodological quality. Whereas only a limited number of studies provided comprehensive discussions of their strengths and limitations [36, 42, 44, 48, 59, 60, 63, 67].

The study used the appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies (AXIS), detailed in Table 4, revealed several key findings across different study designs. Out of the 29 cross-sectional studies, 11 were medium and 18 high quality, demonstrating a low risk of bias. Studies commonly demonstrated clarity in aims and appropriate study design for the study question. Many of them used sampling frame that makes the results fairly generalizable (such as registries), however, many lacked justifications for sample size as well as detailed statistical methods, as seen in AlHammad et al. [45]. And almost all of them were unclear in terms of dealing with non-responders, raising concern about potential difference between responders and non-responders which might affect how representative the sample is. It worth mentioning that each study used different measures/ questions of access to oral health care services, but all used relevant ways to assess the research aim. Qualitative studies, like those by Abduludin et al. [33] and Parry et al. [55], they were generally well-aligned between methodologies and research questions but often failed to address the influence of researchers and their theoretical positioning on their study findings. Case-control studies, exemplified by Du et al. [38] and Mansoor et al. [54], demonstrated good comparability and valid outcome measurements but frequently did not explicitly state strategies to address confounding factors. Across all designs, ethical standards were typically well-maintained, though improvements in sample justification, detailed data analysis, and addressing researcher influence were needed.

Discussion

This study systematically reviewed barriers and facilitators of oral healthcare access for children with disabilities, adopting Levesque et al.’s healthcare model of access as an a priori framework [20]. Among the 36 studies included, the majority (31 out of 36) explored specific dimensions and abilities of access to healthcare, though not all aspects were equally covered.

The main findings of the review were that only 7 out of 36 studies mentioned or indicated approachability, which ignores the contribution of healthcare professionals in the oral healthcare encounter, 9 out of 36 studies mentioned acceptability, whilst 12 out of 36 mentioned appropriateness, therefore failing to consider issues such as reasonable adjustments. In contrast, 24 out of 36 studies focused on the patient’s ability to engage. This discrepancy suggests that there may be a prevailing attitude that children with disabilities are the “problem” rather than recognizing that the barriers lie within the oral healthcare system itself. This observation aligns with the medical model of care, which views individuals as the issue, as opposed to the social model of disability [26], which focuses on the barriers imposed by the healthcare system. Moreover, children with profound autism and complex medical conditions face additional obstacles in accessing dental care, highlighting the need for a social model of disability to address systemic challenges.

Accessing dental care for carers of children with disabilities presents a range of barriers. Limited oral health awareness and knowledge of available services [35,36,37,38,39,40], coupled with a lack of information and awareness about dentists willing to treat children with disabilities [40], all contribute to difficulties in finding suitable dental providers. There is a shortage of dentists experienced in treating children with intellectual disabilities, plus a lack of dentists’ knowledge and training in providing care further restricts access to appropriate dental care [48, 49]. The difficulties faced by dentists while treating children with disabilities may stem from inadequate education and training in this area. Research argues that special care dentistry is often omitted from dental curricula [68, 69], leaving future dentists ill-prepared to interact with and treat individuals with disabilities. This highlights the need for comprehensive dental education programs that prepare undergraduate dental students to effectively interact with and treat children with disabilities [70]. Increasing the exposure of dental students to patients with disabilities has proven to enhance their skills, foster positive attitudes, and boost their competence and confidence [71, 72]. Therefore, targeted training for future dental professionals can play a crucial role in supporting the inclusion of children with disabilities in oral health initiatives and reducing oral health disparities.

While the included studies shed light on barriers to dental care access, the discussion around facilitators lacks consistency. Dental outreach programs [33], parental education [57, 63, 65], and collaboration between medical and dental systems [61] have significant potential to improve oral health outcomes and accessibility for children with disabilities. Ensuring parents and caregivers have appropriate and accessible information and health education appears vital to overcoming barriers [73]. Collaborative and multidisciplinary care emphasizes the benefits of continuity of care when patients interact with multiple services [36].

The systematic review has demonstrated that there is a broad international interest in the area, with evidence from a number of countries. This diversity enhances the generalizability of the findings, offering a comprehensive view that spans multiple research environments and contexts. The prominent contributions from countries like the United States and India highlight regions with strong research infrastructure and focus. Meanwhile, the involvement of other nations underscores the universal relevance and collaborative nature of the research field, reflecting a global commitment to advancing knowledge.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this systematic review lies in its use of a conceptual framework to synthesize findings on oral healthcare access, mapping barriers and facilitators to provider and user characteristics, dimensions and abilities. Employing a systematic and comprehensive approach in collecting and identifying papers minimized the likelihood of missing relevant studies. The methodology used establishes a transparent link between the primary research and the conclusions drawn in this review. The inclusion of multiple reviewers in all study stages also served to reduce selection bias. However, using an existing framework poses a potential limitation, risking oversight of other relevant themes. To address this concern, all authors independently conducted searches for additional themes that could enhance the framework but failed to identify any. Only five papers included in this review adopted a theoretical model of access as a framework to guide the research. Two studies [33, 44] used Levesque’s framework, another [52] employed the Institution of Medicine model of healthcare utilization, one [53] applied the Behavioral Model of Health Services Use, finally, one [40] utilized the Modified Penchansky’s 5A classification. While the remaining 31 included papers did not incorporate a theoretical model of access. Nevertheless, the adoption of Levesque’s framework allowed consolidation of the barriers and facilitators to dental care access from multiple studies, enabling categorization into the five dimensions and five abilities, resulting in a more comprehensive overview.

Implications and future recommendations

This mixed methods systematic review contributes to understanding the complex landscape of oral healthcare access for children with disabilities. Applying Levesque et al.’s [20] theoretical framework provides a comprehensive understanding of barriers and facilitators affecting access. Identified barriers have implications for policymakers, healthcare providers, and educational institutions. This includes collaboration between dental and other medical systems, which appears vital to ensure coordinated and comprehensive care and assists in ensuring the provision of multidisciplinary care. Reducing the cost of dental treatment, insurance coverage, and/or providing access to free or subsidized dental care services for individuals with disabilities are crucial facilitators. Exposing dental professionals to individuals with disabilities during learning years and improving their communications skills with different patients’ group can enhance their skills, confidence, and willingness to provide care to individuals with disabilities. Adopting the social model of disability shifts the focus from individuals as the “problem” to systemic barriers, demanding attention.

Future recommendations include studies employing rigorous methodologies and involving various stakeholders such as children, parents/guardians, dental professionals, and policymakers. Utilizing comprehensive and up-to-date frameworks like Levesque’s conceptual framework enables a deeper exploration of the barriers and facilitators associated with oral health care services for children with disabilities. Addressing barriers and leveraging facilitators, provides the foundations for equitable access to oral healthcare for children with disabilities. This aims to improve their oral health outcomes and contribute to their overall well-being and quality of life.

Conclusions

This review highlights the diverse and global interest in addressing oral healthcare access for children with disabilities, reflecting a collaborative and universal commitment to improving health outcomes. The findings underscore the need for systemic changes, including better training for dental professionals, increased collaboration across healthcare systems, and policy adjustments to reduce financial barriers. By focusing on both barriers and facilitators, this review provides a pathway towards more equitable and effective oral healthcare services for children with disabilities.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- UNICEF:

-

The United Nations Children’s International Emergency Fund

- QuADS:

-

Quality Appraisal for Diverse Studies

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- AXIS:

-

Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies

- JBI:

-

The standardized Joanna Briggs Institute

References

UNICEF. Seen, Counted, Included: Using data to shed light on the well-being of children with disabilities. 2021. https://data.unicef.org/resources/children-with-disabilities-report-2021/. Accessed 5 Nov 2023.

World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). 2023. https://www.who.int/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health Accessed 5 Nov 2023.

Allerton LA, Welch V, Emerson E. Health inequalities experienced by children and young people with intellectual disabilities: a review of literature from the United Kingdom. J Intellect Disabil. 2011;15:269–78.

Zhou N, Wong HM, Wen YF, McGrath C. Oral health status of children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59:1019–26.

Hong CL, Broadbent JM, Thomson WM, Poulton R. The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study: oral health findings and their implications. J Royal Soc N Z. 2020;50:35–46.

Norwood KW Jr, Slayton RL,Council on Children With D, Section on Oral H, Liptak GS, Murphy NA, et al. Oral health care for children with developmental disabilities. Pediatrics. 2013;131:614–9.

Zhou N, Wong HM, McGrath C. Oral health and associated factors among preschool children with special healthcare needs. Oral Dis. 2019;25:1221–8.

Cermak SA, Stein Duker LI, Williams ME, Dawson ME, Lane CJ, Polido JC. Sensory adapted dental environments to enhance oral care for children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45:2876–88.

Stein LI, Polido JC, Cermak SA. Oral care and sensory over-responsivity in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Dent. 2013;35:230–5.

Zhou N, Wong HM, McGrath CPJ. A multifactorial analysis of tooth-brushing barriers among mentally challenged children. J Dent Res. 2019;23:1587–94.

National Research Council. Informal caregivers in the United States: prevalence, caregiver characteristics, and ability to provide care. In: Olson S, editor. The role of human factors in home health care: Workshop summary. US: National Academies Press; 2010.

Porterfield SL, McBride TD. The effect of poverty and caregiver education on perceived need and access to health services among children with special health care needs. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:323–9.

Adyanthaya A, Sreelakshmi N, Ismail S, Raheema M. Barriers to dental care for children with special needs: general dentists’ perception in Kerala, India. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2017;35:216–22.

Nelson LP, Getzin A, Graham D, Zhou J, Wagle EM, McQuiston J, et al. Unmet dental needs and barriers to care for children with significant special health care needs. Pediatr Dent. 2011;33:29–36.

Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9:208.

Aday LA, Andersen RM. Equity of access to medical care: a conceptual and empirical overview. Med Care. 1981;19(12):4–27.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10.

Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34:1273.

Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19:127–40.

Levesque J-F, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:1–9.

Krishnan L, Iyer K, Madan Kumar PD. Barriers to utilisation of dental care services among children with special needs: a systematic review. Indian J Dent Res. 2020;31:486–93.

da Rosa SV, Moysés SJ, Theis LC, Soares RC, Moysés ST, Werneck RI, et al. Barriers in access to dental services hindering the treatment of people with disabilities: a systematic review. Int J Dent. 2020;2020:1–17.

Owens J, Mistry K, Thomas AD. Access to dental services for people with learning disabilities: quality care? Br J Disabil Oral Health. 2011;12:17–27.

Stern C, Lizarondo L, Carrier J, Godfrey C, Rieger K, Salmond S, et al. Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI Evid Implement. 2021;19:120–9.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906.

Oliver M. Understanding disability: From theory to practice. UK: Bloomsbury Publishing; 2018.

Alborz A, McNally R, Glendinning C. Access to health care for people with learning disabilities in the UK: mapping the issues and reviewing the evidence. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10:173–82.

ResearchSoft. T. Endnote 9. Stamford, CT: The Thomson Corporation; 2005. http://endnote.com/. Accessed 5 Nov 2023

Harrison R, Jones B, Gardner P, Lawton R. Quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADS): an appraisal tool for methodological and reporting quality in systematic reviews of mixed-or multi-method studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:1–20.

Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011458.

Joanna Briggs I. The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools for use in JBI systematic reviews. Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cohort Studies. 2017. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools. Accessed 5 May 2024.

Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. JBI Evid Implement. 2015;13:179–87.

Abduludin DMA, Rahman NA, Adnan MM, Yusuf A. Experience of caregivers caring for children with cerebral palsy in accessing oral health care services: a qualitative study. Arch Orofac Sci. 2019;14(2):133–46.

Schultz ST, Shenkin JD, Horowitz AM. Parental perceptions of unmet dental need and cost barriers to care for developmentally disabled children. Pediatr Dent. 2001;23:321–5.

Al Agili DE, Roseman J, Pass MA, Thornton JB, Chavers LS. Access to dental care in Alabama for children with special needs: parents’ perspectives. J Am Dent Assoc. 1939;2004(135):490–5.

Allison PJ, Hennequin M, Faulks D. Dental care access among individuals with Down syndrome in France. Spec Care Dentist. 2000;20:28–34.

Barry S, O’Sullivan EA, Toumba KJ. Barriers to dental care for children with autism spectrum disorder. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2014;15:127–34.

Du RY, Yiu CKY, King NM. Oral health behaviors of preschool children with autism spectrum disorders and their barriers to dental care. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49:453–9.

Junnarkar VS, Tong HJ, Hanna KMB, Aishworiya R, Duggal M. Qualitative study on barriers and coping strategies for dental care in autistic children: parents’ perspective. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2023;33:203–15.

Liu N, Drake M, Kruger E, Tennant M. Determining the barriers to access dental services for people with a disability: a qualitative study. Asia Pac J Health Manag. 2022;17(1):72–83.

Como DH, Florindez-Cox LI, Stein Duker LI, Cermak SA. Oral health barriers for African American caregivers of autistic children. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(24):17067.

de Souza MLP, de Lima PDL, Herkrath FJ. Utilization of dental services by children with autism spectrum conditions: the role of primary health care. Spec Care Dent. 2023;44(1):175–83.

Sabbarwal B, Puranik MP, Uma SR. Oral health status and barriers to utilization of services among down syndrome children in Bengaluru City: a cross-sectional, comparative study. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2018;16:4–10.

Hu K, Da Silva K. Access to oral health care for children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22:497.

AlHammad KAS, Hesham AM, Zakria M, Alghazi M, Jobeir A, AlDhalaan RM, et al. Challenges of autism spectrum disorders families towards oral health care in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Pesqui Bras Odontopediatria Clin Integr. 2020;20:e5178.

Alshihri AA, Al-Askar MH, Aldossary MS. Barriers to professional dental care among children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51:2988–94.

Bhaskar BV, Janakiram C, Joseph J. Access to dental care among differently-abled children in Kochi. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2016;14:29–34.

Brickhouse TH, Farrington FH, Best AM, Ellsworth CW. Barriers to dental care for children in Virginia with autism spectrum disorders. J Dent Child. 2009;76:188–93.

De Jongh AD, Van Houtem C, Van Der Schoof M, Resida G, Broers D. Oral health status, treatment needs, and obstacles to dental care among noninstitutionalized children with severe mental disabilities in The Netherlands. Spec Care Dentist. 2008;28:111–5.

Gerreth K, Borysewicz-Lewicka M. Access barriers to dental health care in children with disability. A questionnaire study of parents. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2016;29:139–45.

Holt S, Parry JA. Parent-reported experience of using a real-time text messaging service for dental appointments for children and young people with autism spectrum conditions: a pilot study. Spec Care Dentist. 2019;39:84–8.

Krishnan L, Iyer K, Kumar PDM. Barriers in dental care delivery for children with special needs in Chennai, India: A mixed method research. Disabil CBR Incl Dev. 2018;29:68–82.

Lai B, Milano M, Roberts MW, Hooper SR. Unmet dental needs and barriers to dental care among children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:1294–303.

Mansoor D, Al Halabi M, Khamis AH, Kowash M. Oral health challenges facing Dubai children with Autism Spectrum Disorder at home and in accessing oral health care. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2018;19:127–33.

Parry JA, Newton T, Linehan C, Ryan C. Dental visits for autistic children: a qualitative focus group study of parental perceptions. JDR Clin Transl Res. 2023;8:36–47.

Puthiyapurayil J, Anupam Kumar TV, Syriac G, R M, Kt R, Najmunnisa. Parental perception of oral health related quality of life and barriers to access dental care among children with intellectual needs in Kottayam, Central Kerala‐A cross sectional study. Spec Care Dentist. 2022;42:177–86.

Rajput S, Kumar A, Puranik MP, Sowmya KR, Chinam N. Oral health perceptions, behaviors, and barriers among differently abled and healthy children. Spec Care Dentist. 2021;41:358–66.

Shyama M, Al-Mutawa SA, Honkala E, Honkala S. Parental perceptions of dental visits and access to dental care among disabled schoolchildren in Kuwait. Odontostomatol Trop Trop Dent J. 2015;38:34–42.

Stein LI, Polido JC, Najera SOL, Cermak SA. Oral care experiences and challenges in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:387–91.

Al Habashneh R, Al-Jundi S, Khader Y, Nofel N. Oral health status and reasons for not attending dental care among 12-to 16-year-old children with Down syndrome in special needs centres in Jordan. Int J Dent Hyg. 2012;10:259–64.

Chi DL, Momany ET, Kuthy RA, Chalmers JM, Damiano PC. Preventive dental utilization for Medicaid-enrolled children in Iowa identified with intellectual and/or developmental disability. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70:35–44.

Kachwinya SM, Kemoli AM, Owino R, Okullo I, Bermudez J, Seminario AL. Oral health status and barriers to oral healthcare among children with cerebral palsy attending a health care center in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22(1):656.

Zhou N, Wong HM, McGrath C. Dental visit experience and dental care barriers among Hong Kong preschool children with special education needs. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2021;31:699–707.

Al-Shehri SAM. Access to dental care for persons with disabilities in Saudi Arabia (Caregivers’ perspective). J Disabil Oral Health. 2012;13:51.

Fenning RM, Steinberg-Epstein R, Butter EM, Chan J, McKinnon-Bermingham K, Hammersmith KJ, et al. Access to dental visits and correlates of preventive dental care in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50:3739–47.

Zahran SS, Bhadila GY, Alasiri SA, Alkhashrami AA, Alaki SM. Access to dental care for children with special health care needs: a cross-sectional community survey within Jeddah. Saudi Arabia J Clin Pediatr Dentistry. 2023;47(1):50–7.

Zickafoose JS, Smith KV, Dye C. Children with special health care needs in CHIP: access, use, and child and family outcomes. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:S85–92.

Dao LP, Zwetchkenbaum S, Inglehart MR. General dentists and special needs patients: does dental education matter? J Dent Educ. 2005;69:1107–15.

DeLucia LM, Davis EL. Dental students’ attitudes toward the care of individuals with intellectual disabilities: relationship between instruction and experience. J Dent Educ. 2009;73:445–53.

Chávez EM, Subar PE, Miles J, Wong A, LaBarre EE, Glassman P. Perceptions of predoctoral dental education and practice patterns in special care dentistry. J Dent Educ. 2011;75:726–32.

Alumran A, Almulhim L, Almolhim B, Bakodah S, Aldossary H, Alrayes SA. Are dental care providers in Saudi Arabia prepared to treat patients with special needs? J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:281–90.

Casamassimo PS, Seale NS, Ruehs K. General dentists’ perceptions of educational and treatment issues affecting access to care for children with special health care needs. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:23–8.

Liu H-Y, Chen J-R, Hsiao S-Y, Huang S-T. Caregivers’ oral health knowledge, attitude and behavior toward their children with disabilities. J Dent Sci. 2017;12:388–95.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the King Salman Center For Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group no KSRG-2023-171.

Funding

The research was funded by the King Salman Center For Disability Research through Research Group no KSRG-2023-171.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A. and J.O: Conceived the ideas, M.A. conducted data collection and analysis, and led the writing process. A.J. and J.O. Contributed to data collection and analysis, and actively participated in the writing. S.B. Provided insights on methods, supported data analysis, and offered feedback on the draft. All authors contributed to manuscript revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable in this section.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alwadi, M.A., AlJameel, A.H., Baker, S.R. et al. Access to oral health care services for children with disabilities: a mixed methods systematic review. BMC Oral Health 24, 1002 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04767-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04767-9