Abstract

Background

Periodontal diseases are prevalent among adult populations. Its diagnosis depends mainly on clinical findings supported by radiographic examinations. In previous decades, cone beam computed tomography has been introduced to the dental field. The aim of this study was to address the diagnostic efficacy of cone-beam computed tomographic (CBCT) imaging in periodontics based on a systematic search and analysis of the literature using the hierarchical efficacy model.

Methods

A systematic search of electronic databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane was conducted in February 2019 to identify studies addressing the efficacy of CBCT imaging in Periodontics. The identified studies were subjected to pre-identified inclusion criteria followed by an analysis using a hierarchical model of efficacy (model) designed for an appraisal of the literature on diagnostic imaging modality. Four examiners performed the eligibility and quality assessment of relevant studies and consensus was reached in cases where disagreement occurred.

Results

The search resulted in 64 studies. Of these, 34 publications were allocated to the relevant level of efficacy and quality assessments wherever applicable. The overall diagnostic accuracy of the included studies showed a low or moderate risk of bias and applicability concerns in the use of CBCT. In addition, CBCT is accurate in identifying periodontal defects when compared to other modalities. The studies on the level of patient outcomes agreed that CBCT is a reliable tool for the assessment of outcomes after the treatment of periodontal defects.

Conclusion

CBCT was found to be beneficial and accurate in cases of infra-bony defects and furcation involvements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Periodontal diseases affect the structures surrounding the teeth [1,2,3]. They range from the mildest form of gingivitis to the most aggressive form of periodontitis. Gingivitis is limited to the inflammation of gingiva without deep involvement of teeth-supporting structures such as the alveolar bone. On the other hand, periodontitis does extend to the alveolar bone [4,5,6,7]. It starts with the formation of a periodontal pocket and, consequently, if not treated, leads to bone and tooth loss. Another manifestation of the periodontal diseases in molar-premolar teeth is the formation of furcation defects [8,9,10,11]. Since gingivitis affects only the soft tissue, its diagnosis and treatment rely solely on clinical findings including redness, puffiness, and bleeding [12,13,14]. However, periodontitis could lead to bone resorption depending on its severity; hence, its diagnosis and treatment planning relies on clinical methods supported by radiographic imaging [15,16,17].

There are several risks to using clinical examination alone, which could prevent the accurate diagnosis of periodontitis, including gingival tissue consistency, inflammation severity, pressure while probing, probe size, probing angulation, and dental restoration existence [18, 19]. In dental practice, practitioners routinely utilize conventional radiography such as periapical, bitewing, and panoramic x-ray to evaluate the bone loss and overall condition of the periodontal disease [18]. Nevertheless, the two-dimensional x-ray has some limitations, mainly due to the overlapping of structures [20]. Thus, the detection of bone craters, inter-radicular bone loss, and lingual and buccal marginal bone loss necessitate the consideration of three-dimensional radiography [17, 21,22,23,24].

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) has been used frequently in the last two decades in dentomaxillofacial region [25]. It has many advantages compared to conventional computed tomography (CT) including low price, low radiation dose, and ease of accommodation at dental offices [25,26,27]. In addition, it has the ability to view the structures in three dimensions [28,29,30]. CBCT images of periodontal bone lesions offer a highly informative value. The spatial representation of the alveolar bone in all three planes has a significant role in periodontology, as treatment decisions and long-term prognosis rely on it [11]. Accordingly, it can play a potential role as an adjunct to clinical examination in the case of periodontal diseases [28, 31, 32].

Evidence-based dentistry aims to identify the best available evidence to justify the efficacy and use of any dental imaging or test in actual practice. Accordingly, Fryback and Thornbury came up with a hierarchal model of efficacy in the early nineties to sort out the best available evidence for a diagnostic tool [33].

There are several published studies on the role of CBCT in periodontal diseases in the literature [13,14,15].

However, the extent to which CBCT is efficient and accurate in the diagnosis, treatment planning, decision-making, and treatment outcomes of periodontal diseases remains ambiguous. On the path to routine use, especially under consideration of higher radiation exposure to patients, the gain in additional information of clinical relevance has to be explored and evaluated. Consequently, we conducted a systematic review to address the efficacy of CBCT in periodontal diseases.

Methods

This review was conducted based on guidelines from Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [34] and guidance from the center for reviews and dissemination (CRD) for undertaking a systematic review in health care [35]. The eligibility criteria for inclusion and exclusion were set. Then, the included studies were assigned to the suitable level of efficacy. In the meantime, the review question was designed according to the PICO (Population, or Problem, Intervention or Exposure, Comparison, Outcome) element [36]. Finally, each study was evaluated for quality using the predetermined tool for quality assessment (QUADAS 2).

Criteria for inclusion

-

I.

Original studies

-

II.

Systematic reviews

-

III.

The study must assess the role of CBCT in plaque-induced periodontal disease

-

IV.

Each study can be on any level of the efficacy model [33]

-

V.

Studies addressing CBCT accuracy should compare it to clinical or radiographic measurements

Criteria for exclusion

-

I.

Case reports

-

II.

Narrative reviews

-

III.

Languages other than English

-

IV.

Studies addressing periapical periodontitis caused by pulpal infection

-

V.

Studies addressing the bone status for the purpose of dental implant

-

VI.

Studies highlighting the use of CBCT to address artificially created bone defects

-

Problem specification:

The research question was defined as “what is the diagnostic efficacy of CBCT in individuals with periodontal diseases?”

-

Literature search:

Four databases PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane, and Web of Science were searched till February 2019 to identify the relevant studies. The search strategy is shown in Table 1.

-

Study retrieval:

The resultant studies were subjected to a duplicate check on the RefWorks database. The studies were then reviewed by four authors for relevance based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. After that, the studies meeting the eligibility criteria were assigned for full-text screening. Where uncertainty was present, discussions were conducted between the authors to reach an agreement on whether to include or exclude a study based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

-

Data extraction & quality assessment:

Finally, each of the selected studies was assigned for data extraction and analysis. After that, each study was allocated its suitable level of efficacy. A Revised Tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS 2) was used for quality assessment. This tool contains four domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. Each domain is assessed in terms of risk of bias and the first three domains are assessed in terms of concerns regarding applicability. Signaling questions are included to help judge the risk of bias [37].

Result

Studies allocation

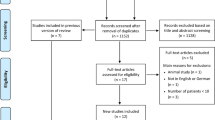

The search strategy of the four databases yielded 1717 articles: PubMed 539, Scopus 746, Cochrane 71, and Web of Science 555. After a duplicate check using RefWorks, the result came up to 1262. These were subjected to the title and abstract screening by the two authors. A set of 65 studies were linked to the full-text review. A total of 28 articles were excluded because they did not possess at least one of the inclusion criteria. Studies reported by [28, 38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] were ex vivo studies and out of our review.

Plaque-induced periodontitis was not addressed, therefore, studies on that issue were excluded. In addition, studies that did not belong to any level of efficacy were disregarded [51,52,53,54,55]. Studies that addressed bone density conducted by Al Zahrani et al. [56] and bone coverage conducted by Ferriera et al. [57] were also excluded. Published studies by Evangelista et al. [58], Sun et al. [59], and Leung et al. [60] discussed only the naturally occurring dehiscence and fenestration, hence, they were disregarded. Studies reported by Goodarzy et al. [61] and Nagao et al. [62] were excluded because they did not include patients having periodontitis. The case report presented by Naitoh et al. [63] was disregarded as well. Studies published in languages other than English; reported by Deng et al. [64]) was excluded. Figure 1 shows the results for systematic reviews according to the PRISMA flow chart. Table 2 shows the studies that were included and their suitable efficacy level.

-

Quality assessment

After allocating each study its suitable efficacy level, special tools of quality assessment were used for each one as described in the literature [37].

-

Technical efficacy studies:

There was no study identified on this level of efficacy.

-

Diagnostic accuracy studies:

The results revealed eighteen studies [65, 69, 71, 74, 76, 81, 84, 86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96] on diagnostic accuracy. The QUADAS-2 assessment tool was used for quality assessment [34]. Table 3 reveals the results of the quality assessment using QUADAS-2.

There were three studies that included a previously published systematic, manual search of the reference lists of the included articles [64, 81, 87], among which one study by Deng et al. [64] was found to be published in a Chinese language and hence excluded.

-

Diagnostic thinking efficacy:

Only one study was found to be on the level of diagnostic thinking efficacy [66]. The author investigated the effect of CBCT on the treatment decision-making after taking into consideration the clinical parameters.

-

Therapeutic efficacy:

In this level of efficacy, only one study, Pajnigara et al. [67], seemed relevant.

-

Patient outcome efficacy:

Our research resulted in eight studies in which CBCT was used to address the patients’ outcomes in relation to periodontal disease. All of the studies are randomized clinical trials [68, 72, 75, 77, 79, 82, 85]. Table 4, the CASP (critical appraisal skills program) checklist, was used to assess outcomes.

-

Societal efficacy:

Only one study was found to be relevant in this level of efficacy, Walter et al. [69]. The quality assessment was done using the QUADAS 2 tool.

Systematic reviews

The remaining six studies [6, 70, 73, 78, 80, 83] were found to be systematic reviews for which the AMSTAR-2 assessment tool [97] was used. It is a popular instrument modified from the original AMSTAR, which contains 16 checklist questions. (Refer to Table 5). The two authors meticulously screened each study in order to give a suitable answer for each checklist question.

Discussion

Alveolar bone loss is considered a primary symptom of periodontal diseases. Mostly, the assessment and treatment decisions depend on clinical measurements supported by conventional imaging modalities. However, 2D imaging has its own limitations for detecting bone defects, including overlapping. An estimation of bone loss bucco-lingually has led to the consideration of 3D imaging. However, to what extent the CBCT is effective in the diagnosis of periodontal diseases is not yet clear. Accordingly, our systematic review was designed to summarize the available evidence according to the hierarchal model of efficacy developed by Fryback et al. [33].

In our systematic review, we decided to exclude studies that are published in any language other than English because of time restriction. In addition, case reports and narrative reviews are considered in the literature as low-evidence studies. Studies addressing periapical conditions and implant-related periodontal problems were also excluded as they are beyond our aspect in this review. In the meantime, it was decided to not include studies conducted ex vivo where the periodontal defects are created artificially since we believe those results will not mimic the CBCT’s performance when conducted on humans.

Technical efficacy level

It seems most of the studies conducted on the use of CBCT in periodontal disease were aimed at performance detection, accuracy estimation, or the treatment outcome assessment. The authors found no study reported in the literature dealt with the technical aspect of CBCT.

Diagnostic accuracy level

As mentioned earlier in this review, the QUADAS 2 tool was used for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Only studies conducted in vivo were included in this review. Some studies did not use explicit reference standards to compare CBCT with other modalities [71, 89, 90, 93, 94].

Cimbaljevic et al. [63] compared the periodontal probing with CBCT in the terms of furcation involvement in the absence of a reference standard. Likewise, Darby et al. [64] addressed the discrepancies in the clinical measurements obtained from patients’ records with their available CBCT images. A study conducted by Suphaanantachat et al. [92] compared CBCT to conventional intraoral radiography. However, they did not use an actual reference standard for comparison. Similarly, Zhu J. et al. [86] has focused on the reproducibility of the different parameters of CBCT for the furcation involvement evaluation, and hence, no reference standard was used.

Diagnostic thinking

A study published by Walter et al. [66] on decision-making revealed discrepancies between clinically and CBCT-based therapeutic treatment approaches. The discrepancy was found after 59–82% of the teeth were investigated to find out whether less invasive or most invasive treatment should be considered. However, they concluded that CBCT provides informative details in cases of furcation involvement, and hence, it is considered a reliable tool in decision-making regarding treatment of furcation involvement.

Therapeutic efficacy

According to our interpretation and in correlation with the hierarchical model of efficacy [33], we found that the study conducted by Pajnigara et al. [67] fits on this level. They investigated the pre and post-surgical measurements of clinical and CBCT for furcation defects. Although they reported statistically significant differences between; clinical-presurgery CBCT (P < 0.0001, 95% CI) and clinical-post surgery CBCT; the three-dimensional imaging gives dental practitioners the chance to optimize treatment decisions and assess the degree of healing more effectively.

Patient’s outcome efficacy

Our systematic review has revealed eight studies that used CBCT to assess the results of treatment provided for periodontal diseases [68, 72, 75, 77, 79, 82, 85, 98]. However, it seems that this study is in disagreement with a previously published review [6]. They did not identify any study on the level of patient outcome. The reason for this could be the difference between our inclusion and exclusion criteria and theirs. All studies agreed that CBCT is a reliable tool in the assessment of the results of treatment using a bone graft.

Societal efficacy

The study reported by Walter et al. [69] has shown that the use of CBCT decreases the cost and time for periodontitis screening. However, CBCT should only be advised in cases of advanced therapy. Further studies with a sufficient number of patients were suggested.

Systematic reviews

Our review has resulted in six studies, which are systematic reviews. Each review is supposed to adhere to the criteria provided by AMSTAR and scores YES whenever applicable. The review published by Haas et al. [78] did not elaborate on whether they included the study registries or consulted content experts in the field in terms of comprehensive literature search strategy. Although a meta-analysis was conducted in such a review, the review authors did not assess the potential impact of risk of bias on the results of the meta-analysis or other evidence synthesis. Moreover, the authors did not carry out an adequate investigation of publication bias (small-study bias) or discuss its likely impact on the results of the review. Based on our interpretation, the study has not reported any source of funding or mentioned any conflict of interest.

The study by Walter et al. [79] did not clearly have an explicit statement that the review methods were established prior to the conduct of the review and did not justify any significant deviations from the protocol. In addition, only one database has been searched for relevant studies. According to the AMSTAR2 criteria, the included studies were not described adequately. The study has not reported on the source of funding for the individual studies included in the review. To our knowledge, the risk of bias has not been elaborated upon in the relevant sites in the review. Moreover, the review authors did not account for the risk of bias in individual studies when interpreting or discussing the results of the review. In addition, the authors have not reported any source of conflict including any funding they received for conducting the review.

The review by Anter et al. addressed the accuracy of the CBCT as a tool for the measurement of alveolar bone loss in periodontal defects. However, the authors did not report that they followed PICO, which is a framework for review question formulation [36]. In terms of a comprehensive search strategy, we saw that this review did not fulfill the criteria regarding study registries and expert consultation in the field. Furthermore, the authors did not conduct the search in duplicate for the purpose of study selection. The review authors had also not performed data extraction in duplicates. According to our interpretation, the included studies were not described in appropriate detail. Additionally, the source of funding for each relevant individual study was not reported.

The study reported by Choi et al. [80] did not specify whether if there was a deviation from protocol, meta-analysis plan, or causes of heterogeneity if appropriate. In addition, a list of the excluded study in association with a justification for exclusion of each potential study has not been provided. Regardless of whether it is one of the targets of the review, this review has not discussed any potential risk of bias of the included studies. Moreover, the source of funding of each included study was also not reported. It could be included that this review does fulfill the AMSTAR2 [97] checklist to some extent.

The review by Woelber et al. [83] neither mentions any deviation from protocol whenever applicable nor elaborates on if is a plan for meta-analysis, if appropriate. In addition, a plan for investigating the possible causes, if appropriate, regarding heterogeneity was also not reported. The source of funding for each included study was not reported either. To some extent, the review fulfills the checklist of AMSTAR2.

According to our systematic review and AMSTAR2 tool, we found the review conducted by Nikolic-Jakoba et al. [6] best fulfills the tool criteria. However, the study’s authors did not justify the reason for exclusion of each potentially relevant study from the review. As other reviews were included in our study, the source of funding of each included publication was not reported.

Conclusion

We concluded that most of the studies conducted on the rule of CBCT in periodontal diseases were at diagnostic accuracy level followed by the patient outcome level. Accordingly, it was found that CBCT is quite beneficial and accurate in the diagnosis of infra-bony defects and furcation involvement. Similarly, it is reliable in the assessment of the outcome of periodontal surgery and regenerative therapy. Furthermore, more studies with a larger cohort on the level of diagnostic thinking, therapeutic, and societal efficacy are needed to set up a clear guideline and evidence for the usefulness of CBCT.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CBCT:

-

Cone beam computed tomography

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred items for systematic review and meta-analysis

- CRD:

-

Center for reviews and dissemination

- PICO:

-

Population, or Problem, Intervention or Exposure, Comparison (if appropriate), Outcome you would like to measure or achieve

- QUADAS2:

-

Quality assessment tool for diagnostic accuracy studies

- CASP:

-

Critical appraisal skills program

- AMSTAR:

-

A measurement tool to assess systematic review

- 2D:

-

Two-dimensional

- 3D:

-

Three-dimensional

References

Flemmig TF. Periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4(1):32–8.

Highfield J. Diagnosis and classification of periodontal disease. Aust Dent J. 2009;54(Suppl 1):S11–26.

Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet (London, England). 2005;366(9499):1809–20.

Loe H, Anerud A, Boysen H, Morrison E. Natural history of periodontal disease in man. Rapid, moderate and no loss of attachment in Sri Lankan laborers 14 to 46 years of age. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13(5):431–45.

Burt B. Position paper: epidemiology of periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 2005;76(8):1406–19.

Nikolic-Jakoba N, Spin-Neto R, Wenzel A. Cone beam computed tomography for detection of Intrabony and furcation defects: a Systematic review based on a hierarchical model for diagnostic efficacy. J Periodontol. 2016;87(6):630–44.

Jordan RCK. Diagnosis of periodontal manifestations of systemic diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2004;34:217–29.

Listgarten MA. Periodontal probing: what does it mean? J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7(3):165–76.

Tugnait A, Clerehugh V, Hirschmann PN. The usefulness of radiographs in diagnosis and management of periodontal diseases: a review. J Dent. 2000;28(4):219–26.

Tyndall DA, Rathore S. Cone beam CT diagnostic applications: caries, periodontal bone assessment, and endodontic applications. Dent Clin N Am. 2008;52(4):825–41 vii.

Braun X, Ritter L, Jervoe-Storm P-M, Frentzen M. Diagnostic accuracy of CBCT for periodontal lesions. Clin Oral Investig. 2014;18(4):1229–36.

Summers A. Gingivitis: diagnosis and treatment. Emerg Nurse. 2009;17(1):18–20 quiz 35.

Bailey DL, Barrow S-Y, Cvetkovic B, Musolino R, Wise SL, Yung C, et al. Periodontal diagnosis in private dental practice: a case-based survey. Aust Dent J. 2016;61(2):244–51.

Garcia-Pola M-J, Rodriguez-Lopez S, Fernanz-Vigil A, Bagan L, Garcia-Martin J-M. Oral hygiene instructions and professional control as part of the treatment of desquamative gingivitis. Systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2019;24(2):e136–44.

Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. The bacterial etiology of destructive periodontal disease: current concepts. J Periodontol. 1992;63(4 Suppl):322–31.

Armitage GC. The complete periodontal examination. Periodontol 2000. 2004;34:22–33.

Taba MJ, Kinney J, Kim AS, Giannobile WV. Diagnostic biomarkers for oral and periodontal diseases. Dent Clin N Am. 2005;49(3):551–71 vi.

Wolf DL, Lamster IB. Contemporary concepts in the diagnosis of periodontal disease. Dent Clin N Am. 2011;55(1):47–61.

Albandar JM, Brunelle JA, Kingman A. Destructive periodontal disease in adults 30 years of age and older in the United States, 1988-1994. J Periodontol. 1999;70(1):13–29.

Facial radiology (Evidence-based guidelines) ISSN 1681–6803 MJ-XA-12-001-EN-C Energy Protection Radiation No 172 Cone beam CT for dental and maxillofacial radiology (Evidence-based guidelines) [Internet]. 2012. Available from: http://www.sedentexct.eu/files/radiation_protection_172.pdf.

Offenbacher S. Periodontal diseases: pathogenesis. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1(1):821–78.

Ozmeric N, Kostioutchenko I, Hagler G, Frentzen M, Jervoe-Storm P-M. Cone beam computed tomography in assessment of periodontal ligament space: in vitro study on artificial tooth model. Clin Oral Investig. 2008;12(3):233–9.

Hashimoto K, Kawashima S, Araki M, Iwai K, Sawada K, Akiyama Y. Comparison of image performance between cone beam computed tomography for dental use and four-row multidetector helical CT. J Oral Sci. 2006;48(1):27–34.

Loubele M, Maes F, Schutyser F, Marchal G, Jacobs R, Suetens P. Assessment of bone segmentation quality of cone beam CT versus multislice spiral CT: a pilot study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102(2):225–34.

Shukla S, Chug A, Afrashtehfar KI. Role of cone beam computed tomography in diagnosis and treatment planning in dentistry: an update. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2017;7(Suppl 3):S125–36.

Orentlicher G, Goldsmith D, Abboud M. Computer-guided planning and placement of dental implants. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2012;20(1):53–79.

Mohan R, Singh A, Gundappa M. Three-dimensional imaging in periodontal diagnosis - utilization of cone beam computed tomography. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15(1):11–7.

Takeshita WM, Vessoni Iwaki LC, Da Silva MC, Tonin RH. Evaluation of diagnostic accuracy of conventional and digital periapical radiography, panoramic radiography, and cone beam computed tomography in the assessment of alveolar bone loss. Contemp Clin Dent. 2014;5(3):318–23.

Jeffcoat MK. Radiographic methods for the detection of progressive alveolar bone loss. J Periodontol. 1992;63(4 Suppl):367–72.

Swennen GRJ, Mommaerts MY, Abeloos J, De Clercq C, Lamoral P, Neyt N, et al. A cone beam CT based technique to augment the 3D virtual skull model with a detailed dental surface. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38(1):48–57.

Worthington P, Rubenstein J, Hatcher DC. The role of cone beam computed tomography in the planning and placement of implants. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(Suppl):19S–24S.

Alqerban A, Hedesiu M, Baciut M, Nackaerts O, Jacobs R, Fieuws S, et al. Pre-surgical treatment planning of maxillary canine impactions using panoramic vs cone beam CT imaging. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2013;42(9):20130157.

Fryback DG, Thornbury JR. The efficacy of diagnostic imaging. Med Decis Mak. 1991;11(2):88–94.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Tacconelli E. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(4):226. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70065-7.

Speckman RA, Friedly JL. Asking structured, answerable clinical questions using the population, intervention/comparator, outcome (PICO) framework: PM R; 2019.

Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–36.

Bagis N, Kolsuz ME, Kursun S, Orhan K. Comparison of intraoral radiography and cone beam computed tomography for the detection of periodontal defects: an in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:64.

Almeida VC, Pinheiro LR, Salineiro FCS, Mendes FM, Neto JBC, Cavalcanti MGP, et al. Performance of cone beam computed tomography and conventional intraoral radiographs in detecting interproximal alveolar bone lesions: a study in pig mandibles. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17(1):100.

Fleiner J, Hannig C, Schulze D, Stricker A, Jacobs R. Digital method for quantification of circumferential periodontal bone level using cone beam CT. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17(2):389–96.

Kamburoglu K, Kolsuz E, Murat S, Eren H, Yuksel S, Paksoy CS. Assessment of buccal marginal alveolar peri-implant and periodontal defects using a cone beam CT system with and without the application of metal artefact reduction mode. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2013;42(8):20130176.

Misch KA, Yi ES, Sarment DP. Accuracy of cone beam computed tomography for periodontal defect measurements. J Periodontol. 2006;77(7):1261–6.

Mol A, Balasundaram A. In vitro cone beam computed tomography imaging of periodontal bone. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2008;37(6):319–24.

Noujeim M, Prihoda T, Langlais R, Nummikoski P. Evaluation of high-resolution cone beam computed tomography in the detection of simulated interradicular bone lesions. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2009;38(3):156–62.

Salineiro FCS, Gialain IO, Kobayashi-Velasco S, Pannuti CM, Cavalcanti MGP. Detection of furcation involvement using periapical radiography and 2 cone beam computed tomography imaging protocols with and without a metallic post: an animal study. Imaging Sci Dent. 2017;47(1):17–24.

Vandenberghe B, Jacobs R, Yang J. Detection of periodontal bone loss using digital intraoral and cone beam computed tomography images: an in vitro assessment of bony and/or infrabony defects. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2008;37(5):252–60.

Vandenberghe B, Jacobs R, Yang J. Diagnostic validity (or acuity) of 2D CCD versus 3D CBCT-images for assessing periodontal breakdown. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104(3):395–401.

Kolsuz ME, Bagis N, Orhan K, Avsever H, Demiralp KO. Comparison of the influence of FOV sizes and different voxel resolutions for the assessment of periodontal defects. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2015;44(7):20150070.

Kamburoglu K, Yeta EN, Yilmaz F. An ex vivo comparison of diagnostic accuracy of cone beam computed tomography and periapical radiography in the detection of furcal perforations. J Endod. 2015;41(5):696–702.

Elashiry M, Meghil MM, Kalathingal S, Buchanan A, Elrefai R, Looney S, et al. Application of radiopaque micro-particle fillers for 3-D imaging of periodontal pocket analogues using cone beam CT. Dent Mater. 2018;34(4):619–28.

Lim H-C, Jeon S-K, Cha J-K, Lee J-S, Choi S-H, Jung U-W. Prevalence of cervical enamel projection and its impact on furcation involvement in mandibular molars: a cone beam computed tomography study in Koreans. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2016;299(3):379–84.

Ozcan G, Sekerci AE. Classification of alveolar bone destruction patterns on maxillary molars by using cone beam computed tomography. Niger J Clin Pract. 2017;20(8):1010–9.

Yang Y, Yang H, Pan H, Xu J, Hu T. Evaluation and new classification of alveolar bone dehiscences using cone beam computed tomography in vivo. Int J Morphol. 2015;33:361–8.

Amorfini L, Migliorati M, Signori A, Silvestrini-Biavati A, Benedicenti S. Block allograft technique versus standard guided bone regeneration: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2014;16(5):655–67.

Alshaer S, Alhaffar I, Khattab R. Evaluating change in radiographic bone density via cone beam computed tomography before and after surgery to patients with chronic periodontitis. Int J Pharmaceutical Sci Rev Res. 2013;23:143–7.

Al-Zahrani MS, Elfirt EY, Al-Ahmari MM, Yamany IA, Alabdulkarim MA, Zawawi KH. Comparison of cone beam computed tomography-derived alveolar bone density between subjects with and without aggressive periodontitis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(1):ZC118–21.

Ferreira PP, Torres M, Campos PSF, Vogel CJ, de Araujo TM, Rebello IMCR. Evaluation of buccal bone coverage in the anterior region by cone beam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2013;144(5):698–704.

Evangelista K, de Faria VK, Bumann A, Hirsch E, Nitka M, Silva MAG. Dehiscence and fenestration in patients with Class I and Class II Division 1 malocclusion assessed with cone beam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;138(2):133.e1–7 discussion 133-5.

Sun L, Zhang L, Shen G, Wang B, Fang B. Accuracy of cone beam computed tomography in detecting alveolar bone dehiscences and fenestrations. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2015;147(3):313–23.

Leung CC, Palomo L, Griffith R, Hans MG. Accuracy and reliability of cone beam computed tomography for measuring alveolar bone height and detecting bony dehiscences and fenestrations. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2010;137(4 Suppl):S109–19.

Goodarzi Pour D, Romoozi E, Soleimani SY. Accuracy of cone beam computed tomography for detection of bone loss. J Dent (Tehran). 2015;12(7):513–23.

Nagao J, Mori K, Kitasaka T, Suenaga Y, Yamada S, Naitoh M. Quantification and visualization of alveolar bone resorption from 3D dental CT images. Int J Computer Assisted Radiol Surg. 2007;2:43–53.

Naitoh M, Yamada S, Noguchi T, Ariji E, Nagao J, Mori K, et al. Three-dimensional display with quantitative analysis in alveolar bone resorption using cone beam computerized tomography for dental use: a preliminary study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2006;26(6):607–12.

Deng Y, Wang C, Li T, Li A, Gou J. An application of cone beam CT in the diagnosis of bone defects for chronic periodontitis. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2015;50(1):7–12.

Nagao J, Kitasaka T, Mori K, Suenaga Y, Shohzoh Yamada MN. Three-dimensional analysis of alveolar bone resorption by image processing of 3-D dental CT images. J Med Imaging. 2006;6144.

Walter C, Kaner D, Berndt DC, Weiger R, Zitzmann NU. Three-dimensional imaging as a pre-operative tool in decision making for furcation surgery. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36(3):250–7.

Pajnigara N, Kolte A, Kolte R, Pajnigara N, Lathiya V. Diagnostic accuracy of cone beam computed tomography in identification and postoperative evaluation of furcation defects. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2016;20(4):386–90.

Grimard BA, Hoidal MJ, Mills MP, Mellonig JT, Nummikoski PV, Mealey BL. Comparison of clinical, periapical radiograph, and cone beam volume tomography measurement techniques for assessing bone level changes following regenerative periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 2009;80(1):48–55.

Walter C, Weiger R, Dietrich T, Lang NP, Zitzmann NU. Does three-dimensional imaging offer a financial benefit for treating maxillary molars with furcation involvement? A pilot clinical case series. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23(3):351–8.

Walter C, Schmidt JC, Dula K, Sculean A. Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) for diagnosis and treatment planning in periodontology: a systematic review. Quintessence Int. 2016;47(1):25–37.

Walter C, Weiger R, Zitzmann NU. Accuracy of three-dimensional imaging in assessing maxillary molar furcation involvement. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37(5):436–41.

Gupta SJ, Jhingran R, Gupta V, Bains VK, Madan R, Rizvi I. Efficacy of platelet-rich fibrin vs. enamel matrix derivative in the treatment of periodontal intrabony defects: a clinical and cone beam computed tomography study. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2014;16(3):86–96.

Anter E, Zayet MK, El-Dessouky SH. Accuracy and precision of cone beam computed tomography in periodontal defects measurement (systematic review). J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2016;20(3):235–43.

de Faria VK, Evangelista KM, Rodrigues CD, Estrela C, de Sousa TO, Silva MAG. Detection of periodontal bone loss using cone beam CT and intraoral radiography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2012;41(1):64–9.

Khosropanah H, Shahidi S, Basri A, Houshyar M. Treatment of Intrabony defects by DFDBA alone or in combination with PRP: a Split-mouth randomized clinical and three-dimensional radiographic trial. J Dent (Tehran). 2015;12(10):764–73.

Feijo CV, de Lucena JGF, Kurita LM, Pereira SL da S. Evaluation of cone beam computed tomography in the detection of horizontal periodontal bone defects: an in vivo study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2012;32(5):e162–8.

Bhavsar NV, Trivedi SR, Dulani K, Brahmbhatt N, Shah S, Chaudhri D. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of effect of risedronate 5 mg as an adjunct to treatment of chronic periodontitis in postmenopausal women (12-month study). Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(8):2611–9.

Haas LF, Zimmermann GS, De Luca CG, Flores-Mir C, Correa M. Precision of cone beam CT to assess periodontal bone defects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2018;47(2):20170084.

Pajnigara NG, Kolte AP, Kolte RA, Pajnigara NG. Volumetric assessment of regenerative efficacy of demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft with or without amnion membrane in grade II furcation defects: a cone beam computed tomography study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2017;37(2):255–62.

Choi IGG, Cortes ARG, Arita ES, Georgetti MAP. Comparison of conventional imaging techniques and CBCT for periodontal evaluation: a systematic review. Imaging Sci Dent. 2018;48(2):79–86.

Raichur PS, Setty SB, Thakur SL, Naikmasur VG. Comparison of radiovisiography and digital volume tomography to direct surgical measurements in the detection of infrabony defects. J Clin Exp Dent. 2012;4(1):e43–7.

Dutra BC, Oliveira AMSD, Oliveira PAD, Manzi FR, Cortelli SC, de Miranda CLSSO, et al. Effect of 1% sodium alendronate in the non-surgical treatment of periodontal intraosseous defects: a 6-month clinical trial. J Appl Oral Sci. 2017;25(3):310–7.

Woelber JP, Fleiner J, Rau J, Ratka-Kruger P, Hannig C. Accuracy and usefulness of CBCT in periodontology: a Systematic review of the literature. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2018;38(2):289–97.

George Marinescu A, Boariu M, Rusu D, Stratul S-I, Ogodescu A. Reliability of CBCT as an assessment tool for mandibular molars furcation defects. Prog Biomed Opt Imaging - Proc SPIE. 2013;8925.

Nemoto Y, Kubota T, Nohno K, Nezu A, Morozumi T, Yoshie H. Clinical and CBCT evaluation of combined periodontal regenerative therapies using enamel matrix derivative and Deproteinized bovine bone mineral with or without collagen membrane. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2018;38(3):373–81.

Qiao J, Wang S, Duan J, Zhang Y, Qiu Y, Sun C, et al. The accuracy of cone beam computed tomography in assessing maxillary molar furcation involvement. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41(3):269–74.

Moradi Haghgoo J, Shokri A, Khodadoustan A, Khoshhal M, Rabienejad N, Farhadian M. Comparison the accuracy of the cone beam computed tomography with digital direct intraoral radiography, in assessment of periodontal osseous lesions. Avicenna J Dent Res. 2014;6.

Banodkar AB, Gaikwad RP, Gunjikar TU, Lobo TA. Evaluation of accuracy of cone beam computed tomography for measurement of periodontal defects: a clinical study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2015;19(3):285–9.

Cimbaljevic MM, Spin-Neto RR, Miletic VJ, Jankovic SM, Aleksic ZM, Nikolic-Jakoba NS. Clinical and CBCT-based diagnosis of furcation involvement in patients with severe periodontitis. Quintessence Int. 2015;46(10):863–70.

Darby I, Sanelli M, Shan S, Silver J, Singh A, Soedjono M, et al. Comparison of clinical and cone beam computed tomography measurements to diagnose furcation involvement. Int J Dent Hyg. 2015;13(4):241–5.

Li F, Jia PY, Ouyang XY. Comparison of measurements on cone beam computed tomography for periodontal Intrabony defect with intra-surgical measurements. Chin J Dent Res. 2015;18(3):171–6.

Guo Y-J, Ge Z, Ma R, Hou J, Li G. A six-site method for the evaluation of periodontal bone loss in cone beam CT images. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2016;45(1):20150265.

Zhu J, Ouyang XY. Assessing maxillary molar furcation involvement by cone beam computed tomography. Chin J Dent Res. 2016;19(3):145–51.

Suphanantachat S, Tantikul K, Tamsailom S, Kosalagood P, Nisapakultorn K, Tavedhikul K. Comparison of clinical values between cone beam computed tomography and conventional intraoral radiography in periodontal and infrabony defect assessment. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2017;46(6):20160461.

Padmanabhan S, Dommy A, Guru SR, Joseph A. Comparative evaluation of cone beam computed tomography versus direct surgical measurements in the diagnosis of mandibular molar furcation involvement. Contemp Clin Dent. 2017;8(3):439–45.

Zhang W, Foss K, Wang B-Y. A retrospective study on molar furcation assessment via clinical detection, intraoral radiography and cone beam computed tomography. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18(1):75.

Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JSW, Zhang C, Li S, Sun F, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8(1):2–10.

Gupta V, Bains VK, Singh GP, Jhingran R. Clinical and cone beam computed tomography comparison of NovaBone dental putty and PerioGlas in the treatment of mandibular class II furcations. Indian J Dent Res. 2014;25(2):166–73.

Acknowledgments

No other contributors to acknowledge.

Funding

No funding was provided for this systematic review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HA: Literature search, analyzing individual studies, manuscript preparation and review; AAD: Literature search, analyzing individual studies, manuscript review; AA: Analyzing individual studies, manuscript review; ZA: Literature search, manuscript review. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research committee at the faculty of dentistry in King Khalid University has approved the study proposal. Since it is a review, the consent of participants is not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Assiri, H., Dawasaz, A.A., Alahmari, A. et al. Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) in periodontal diseases: a Systematic review based on the efficacy model. BMC Oral Health 20, 191 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-020-01106-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-020-01106-6