Abstract

Background

Early childhood caries (ECC) affects millions of children up to 6 years old. Its treatment positively impacts the quality of life of children and their families. However, there is no consensus on how to treat ECC. Thus, we performed a scoping review to identify the recommended procedures for the management of ECC lesions.

Methods

A search was performed in PubMed, Scopus, The Cochrane Library, The International Guideline Library and pediatric dentistry associations around the world were contacted by email for unpublished search documents. ECC guidelines/guidance/policies were considered eligible regardless of language and publication date.

Results

From a total of 828 references, 52 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and 22 included in the scoping review. We found different procedures recommendations for the management of ECC lesions. For incipient lesions, minimally invasive methods such as professional fluoride and cariostatic (silver diamine) applications, as well as surveillance were recommended. If restoration was required, the recommended materials were glass ionomer cement, composite resin, amalgam and stainless-steel crown. Interim restorations and Atraumatic Restorative Treatment (ART) were also recommended. Extractions have been suggested for teeth with lesions with pulpal involvement, depending on the child’s behaviour and other clinical conditions.

Conclusions

Non-operative procedures, restorative and extraction were recommended for the management of ECC, depending on the extent of the lesions. There is no difference between different management guidelines/guidance/policies for ECC lesions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Millions of children under 6 years of age have early childhood caries (ECC) globally [1,2,3]. This condition is a multifactorial and dynamic disease characterized by “the presence of one or more decayed (non-cavitated or cavitated lesions), missing (due to caries), or filled surfaces, in any primary tooth of a child under age six” [2, 4]. The prevalence of this condition is closely related to the child’s age. Thus, while the mean ECC prevalence in children at 1 year of age was 17%, among those with 5-year-olds, these rates are higher than 50% [2].

In addition to its high prevalence, ECC is a matter of concern because of the severe implications it may have on the quality of life and well-being of children and their families. Children with ECC experience impairment of different dimensions in their life. The negative impact can range from difficulty performing daily activities such as eating and sleeping [5, 6] to problems in their growth and development, pain and the need for hospitalizations or emergency room visits [2]. This negative impact may be minimized by the dental treatment under general anesthesia though there is associated morbidity [7], sedation [8] or non-pharmacologic techniques for behavior management [9].

Although scientific evidence [7,8,9] shows that ECC treatment has definite and essential outcomes for improving the child and parents’ quality of life, approximately 621 million children worldwide have untreated cavitated lesions [1]. This alarming data on dental caries and its non-treatment may reveal that low priority is given to children under 6 years of age and the failures in the primary and secondary preventive measures [10]. Also, it should be emphasized that the treatment is technically challenging, and is often dictated by the extent of the lesions, child behavior [11] and the costs for patients/reimbursement system for dentists [12]. The high prevalence of the disease, added to its impact at both individual and collective levels, the possibility of prevention and treatment performed ECC a public health problem [13].

The decision to treat the ECC should be based on individual (such as risk assessment) and family (e.g., compliance of the patient’s caregiver’s willingness to change behaviors that affect oral health) [12, 14], as well as the professional’s experience [11]. As an aid for the decision-making process, there are several published guidelines/guidance/policies. However, considering that ECC is a problem that affects children worldwide, it is essential to know if the recommendations are similar among different countries and over time. This study intends to provide a summary of the guidelines/guidance/policies and a critical analysis of the available information. The aim of this review is to search for scientific evidence of the following question: what are the recommended procedures for the management of ECC lesions?

Methods

This scoping review was developed following the recommendations of Arksey and O’Malley’s [15] and Joanna Briggs Institute [16] and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) (PRISMA-ScR) [17] (Additional file 1). The protocol was registered with the Open Science Framework on 28 January 2019 (https://osf.io/5xh2j). This type of review is indicated to synthesize or group existing evidence on a broad, complex or heterogeneous theme. For this, the following steps are recommended: research question formulation (broad or topic-focused questions), searches of references and their selection according to inclusion and exclusion criteria, extraction and presentation of results, critical evaluation (optional), synthesis of results and consultation (optional). Risk of bias assessment is not applicable for this review [16].

We included guidelines/guidance/policies that recommended procedures for the management of ECC lesions. According to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [18], guidelines involved the evidence-based recommendations; guidance makes evidence-based recommendations developed by independent committees and consulted on by stakeholders; policies are statements relating to institutions positions on various health issues [18]. Language, date of publication and publication status had no restrictions. Observational studies (cross-sectional, case-control and cohort), case reports, interventional studies (clinical trials), reviews and documents (guidelines/guidance/policies) about prevention of dental caries were excluded.

To identify the studies, the following electronic databases were searched in February 2019: PubMed, Scopus, The Cochrane Library, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (Lilacs), Embase and The International Guideline Library. The search strategy included MeSH terms, synonymous, related terms and free terms related to preschool children and dental caries (Table 1). This search strategy was adapted for each electronic database. Furthermore, pediatric dentistry associations around the world were contacted by email or respective website was consulted to identify unpublished guidelines. Duplicated studies were excluded using a bibliographic citation management software (EndNote X7, Thomson Reuters, New York, USA).

The selection of articles was carried independently by two calibrated researchers (KAV and PCF). First of all, the reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of the studies retrieved. Next, to confirm the inclusion, they read the full text of the studies considered potentially eligible in the screening step. Disagreements were solved by consensus.

Data of the included studies were extracted using a standardized data collection form designed for this scoping review. The following data were extracted: authors or association, year, location and recommended procedures management for ECC lesions. A summary of the results was provided in the text and presented in tables. The documents replaced by other updated were presented as Additional file 2.

Results

Study selection

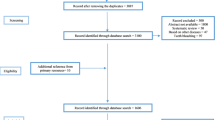

A total of 837 documents were identified in the electronic (database) and manual (email send to Pediatric Dentistry Associations and search in these websites) search. After removing the duplicated studies, 681 remained. Among them, 629 were excluded based on the title and abstract, due to the following reasons: non-issue related (n = 595) and type of study (n = 34). Of the 52 full-text studies assessed for eligibility, 22 remained and were included in this scoping review (Fig. 1). Seven were policies, one was a guidance and 14 were guidelines (Tables 2 and Additional file 2). Of the 22 documents inserted, nine were replaced by updated ones and presented in Additional file 2. The final 13 updated documents are presented in Table 2.

The websites of Pediatric Dentistry Associations were consulted, and emails requesting information about guideline or recommendations for treating carious lesions were sent to representatives of associations from 68 countries. All continents have been contemplated. Of this total of emails sent, only eight responded that they did not have a country-specific guideline (Belgium, Sweden, Kenya, South Africa) or adopted those suggested by American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry and European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry (Serbia, Philippines, Mexico, Croatian). Guidelines of the United States, Brazil, Malaysia, United Kingdom were available on the websites. The document prepared in Brazil was translated and adopted by some Latin American countries, such as Paraguay. A more current version of Chile’s guideline was available on that country’s Ministry of Health website. Documents of Academy of Paediatric Dentistry (United States), European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry (United Kingdom) and Chilean Ministry of Health also where be identified in the electronic databases search.

Considering all the documents, most of the studies were published in English between 2011 and 2018. Documents were identified from the United States, United Kingdom, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Argentina, the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry and the European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry.

Different procedures were suggested for the management of ECC lesions, ranging from surveillance to extraction (Fig. 2). Active surveillance – careful monitoring of lesions progression and application of prevention measures - was recommended for incipient lesions, except for children older than 3 years with high caries risk and whose parents were not engaged [28, 29, 32]. For incipient lesions, other options were fissure and pit sealants [25, 26, 3738], resin infiltration for proximal enamel lesions [26, 40], the use of anti-cariogenic agents [30] (Additional file 2) and fluoride [19, 23, 25, 26, 36, 37, 40]. Home-based fluoride was recommended by just eight studies [19, 21, 23, 32, 37]. For the arrest of cavitated caries lesions, the use of 38% silver diamine fluoride (SDF) was recommended [27], especially for young children [23], just for American Academy and just after 2016.

Almost all documents advocated the restoration of primary teeth with cavitated carious lesion [22, 23, 25, 26, 29, 38,39,40]. Interim therapeutic restorations (ITR) may be indicated for caries control in children with a great deal of cavitated carious lesion, as well as for the uncooperative patient, small children and patients with special health care needs that could not receive permanent restorations [23, 28, 29, 32]. To restore primary teeth, it was recommended the use of different materials/techniques, such as Atraumatic Restorative Treatment - ART [19, 29, 37,38,39]; restoration with glass ionomer cement [19, 26, 29, 37,38,39] or resin-based composites [19, 21, 26, 29, 37,38,39,40] or amalgam [19, 29, 37, 39, 40]; stainless steel crowns [19, 23, 26, 29, 37, 39, 40]. The Hall Technique was first added at 2013 [37]. The provision of prosthetic restoration, fixed or removable, was endorsed in children who lost teeth ([20, 30, 31] Additional file 2).

Extraction was also indicated [25, 26, 40], especially for teeth pulpal involved depending on the patient’s cooperation, medical condition, infection, the extent of caries and potential for malocclusion [40]. No other differences besides of that mentioned above (SDF and Hall Technique) were found among recommendations along time and in different places.

The use of advanced behavior guidance techniques to treat children with ECC was considered in six documents [23,24,25,26, 28, 40].

Discussion

This scoping review was performed to identify what procedures were recommended for the management of ECC lesions and to promote critical analysis of the information available on the guidelines/guidance/policies. Different interventions were suggested for the management of ECC lesions, from active surveillance to extraction, depending on the disease process and the patient’s risk of caries. In fact, it is well known that the clinical decision-making for caries management on children should be based on the patient’s risk levels, current oral health status, age, and the engagement of caregivers with preventive strategies [13, 14].

Active surveillance was proposed by few recommendations, and just for incipient lesions. However, considering that the surveillance is a pivotal component of caries management, it should be recommended for all patients, aiming to both arrest lesions and monitor the progression [13]. For non-cavitated carious lesions, the use of professional fluoride (5% NaF varnish) associated with sealants on occlusal surfaces or with resin infiltration on approximal surfaces increase the chance of arresting or reversing lesions compared with no treatment [41], so whenever possible, these procedures should be performed. One cannot fail to mention, however, that for the resin infiltration, to our knowledge, just a single commercial product holds the patent so that this fact can restrict its use. When it was not available, professionals can use other approaches, such as fluoride toothpaste and dental floss, and/or fluoride varnish, although these conventional management are less effective, probably because they demand a high level of patient compliance [42].

The use of fluoride toothpaste has been recommended in a few documents [22, 23, 32], although it is easy to apply and is currently recommended as a prevention measure secondary to ECC. Only from the document published in Argentina, the recommended fluoride concentration and amount of toothpaste for each age were addressed [19]. However, the recommendations are not out of date. This information has recently been discussed, and it is recommended that for all children a concentration of at least 1000 ppm fluoride should be used for twice-daily brushing, following the recommended amount of toothpaste for each age [4]. For children under 3 years old, the amount of fluoridate toothpaste corresponding to smear size is recommended, while children under 3–6 years old should use the amount corresponding to pea-size [2].

Almost all documents recommended restoring cavitated lesions, which historically is the approach used to management of caries [13]. Nonetheless, it is recognized that although restorative approaches are possible for the management of ECC, low scientific evidence was found for this intervention in anterior teeth [43]. It is known that there is a variety of nonrestorative procedures that can be used to treat carious lesions both on anterior and posterior teeth [41]. Two studies demonstrated that keeping cavities in primary molars without biofilm might be a treatment option to arrest cavitated lesions [44, 45]. The success of this therapy - keep cavitated lesions without inserting restorative materials (non-restorative approach) - depends on the attitudes of patients and their families to brush the lesions and change habits [14, 46].

Although SDF has been used for more than four decades, it was recommended just in 2013 [37]. It can be explained by the fact that at the beginning, few countries used SDF. The number of studies about SDF published in English before 2009 is limited because before this year, SDF was commonly used just in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, China and Japan [47]. Nonetheless, SDF showed to be more effective than other interventions for control caries progression in primary teeth [48] as well as to prevent dental caries in the entire dentition [49]. Accordingly, one systematic review pointed out that there is a high level of evidence for the potential of the SDF for arrest carious lesion (cavitated and non-cavitated) [43]. This recommendation is confirmed in a document recently published by the World Health Organization [50]. Different restorative materials were recommended to primary teeth, based on the involvement of different surfaces. One systematic review found that there is no different among compomer, resin-modified glass ionomer cement, amalgam and composite resin, but conventional glass ionomer cement had a higher risk of failure in primary molars compared to other materials [51]. On the other hand, another systematic review found that composite resin, compomer, resin-modified glass ionomer cement, and glass ionomer cement showed similar results for the restoration of primary molars [52]. Although ART could be considered an alternative for restoring occlusal [53] and occlusoproximal [53, 54] cavities in primary molars, just six guidelines cited it. Bearing all these aspects in mind, the clinical decision-making to choose one material should consider besides the type of cavity, the patient’s/family’s wish, the professional’s ability, the child’s age, the child’s behavior and treatment’ costs and availability.

Considering that around 9% of pediatric patients presented dental fear/anxiety or dental behavior management problems [55], a portion of the child population may need the use of pharmacological behavior management techniques to perform the dental treatment, but just six documents considered this possibility [22, 23, 25, 26, 28, 40]. Sedation and general anesthesia aimed to provide safe and effective dental care [27, 56] and had proved to improve the child’s behavior in the dental chair along the time [57] and to improve the oral health-related quality-of-life [7], respectively.

Our scoping has limitations that involve the inclusion of only documents available electronically. We recognize that, in some countries, there may be guidelines/policies/guidance in printed books and manuals that were not considered in our study. To minimize this limitation, efforts were performed to request associations from different countries to send any documents regarding the management of ECC lesions.

Recently, a manual was developed and published by the World Health Organization [50]. This document is based on systematic reviews and WHO recommendations. The recommendations for arresting and restoration of carious lesions are similar to those observed in our study. This mainly included the use of sealants, fluoride and minimally invasive techniques for restoration such as ART. Our study advances by presenting information referring to guidelines, policies and guidance from different countries, allowing an overview of the management of ECC lesions. This scoping review brings a summary of the recommendations about the management of ECC lesions, which seems not to be previously described. This broad vision of what the recommendations around the world bring can help during the development/updating of guidelines, as well as it can help the dental team critically analyze guidelines before implementing procedures. Unfortunately, although all efforts were made to find all recommendations, it cannot be ruled out that some of them were not found. Based on our results, it can be concluded that there is no difference among recommendations from different places and from different years about the management of dental caries. Similarly, to the conclusions of a previous systematic review, we endorsed the use of SDF for cavitated or non-cavitated lesions, the use of fluoride varnish for non-cavitated lesions, and a cautious indication of restorative approaches, especially for anterior teeth [43].

Conclusions

ECC management involves analyzing the extent of caries lesions and children’s characteristics, such as their behavior. The documents reviewed are similar in their recommendations; the most indicated procedures were non-operative (such as active surveillance, the use of professional fluoride associated with sealants on occlusal surfaces or with resin infiltration on approximal for arresting or reversing lesions), restorative and extraction.

Availability of data and materials

The data from this scoping review may be made available by the corresponding author through the email.

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

Atraumatic restorative treatment

- ECC:

-

Early childhood caries

- ITR:

-

Interim therapeutic restorations

- PRISMA-ScR:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- SDF:

-

Silver diamine fluoride

References

Kassebaum NJ, Smith AGC, Bernabé E, Fleming TD, Reynolds AE, Vos T, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence, incidence, and disability-adjusted life years for oral conditions for 195 countries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. J Dent Res. 2017;96:380–7.

Tinanoff N, Baez RJ, Diaz Guillory C, Donly KJ, Feldens CA, McGrath C, et al. Early childhood caries epidemiology, aetiology, risk assessment, societal burden, management, education, and policy: global perspective. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2019;29:238–48.

Pitts N, Baez R, Diaz-Guallory C, Donly K, Feldens C, McGrath C, et al. Early childhood caries: IAPD Bangkok declaration. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2019;29:384–6.

Drury TF, Horowitz AM, Ismail AI, Maertens MP, Rozier RG, Selwitz RH. Diagnosing and reporting early childhood caries for research purposes. J Public Health Dent. 1999;59:192–7.

Piva F, Pereira JT, Luz PB, Hugo FN, de Araújo FB. Caries progression as a risk factor for increase in the negative impact on OHRQOL-a longitudinal study. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22:819–28.

Corrêa-Faria P, Daher A, Freire MDCM, de Abreu MHNG, Bönecker M, Costa LR. Impact of untreated dental caries severity on the quality of life of preschool children and their families: a cross-sectional study. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:3191–8.

Knapp R, Gilchrist F, Rodd HD, Marshman Z. Change in children's oral health-related quality of life following dental treatment under general anaesthesia for the management of dental caries: a systematic review. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2017;27:302–12.

Guney SE, Araz C, Tirali RE, Cehreli SB. Dental anxiety and oral health-related quality of life in children following dental rehabilitation under general anesthesia or intravenous sedation: a prospective cross-sectional study. Niger J Clin Pract. 2018;21:1304–10.

Vollú AL, da Costa MDEPR, Maia LC, Fonseca-Gonçalves A. Evaluation of oral health-related quality of life to assess dental treatment in preschool children with early childhood caries: a preliminary study. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2018;42:37–44.

Freire MDCM, Daher A, Costa LR, Corrêa-Faria P, de Brito LC, Bönecker MJS, et al. Caries severity declined besides persistent untreated primary teeth over a 22-year period: trends among children in Goiânia. Brazil Int J Paediatr Dent. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/ipd.12451 [Epub ahead of print].

Rønneberg A, Skaare AB, Hofmann B, Espelid I. Variation in caries treatment proposals among dentists in Norway: the best interest of the child. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2017;18:345–53.

Slayton RL. Clinical decision-making for caries management in children: an update. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37:106–10.

Daly B, Watt R, Batchelor P, Treasure E. Essential dental public health. New York: Oxford Press University; 2002.

Innes NP, Manton DJ. Minimum intervention chiildren’s dentistry – the starting point for a lifetime of oral health. Br Dent J. 2017;223:205–13.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:141–6.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colguhoun H, Levac D. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Available in https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance. Accessed November 2, 2019.

Asociacíon Argentina de Odontologia para Niños. Guías para la atención em odontopediatría: tratamiento. Bol Asoc Argent Odontol Niños. 2006;35:17–32.

Rayner J, Holt R, Blinkhorn F, Duncan K, British Society of Paediatric Dentistry. British Society of Paediatric Dentistry: a policy document on oral health care in preschool children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2003;13:279–85.

Fayle SA, Welbury RR, Roberts JF, British Society of Paediatric Dentistry. BSPD. British Society of Paediatric Dentistry: a policy document on management of caries in the primary dentition. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001;11:153–7.

Kandiah T, Johnson J, Fayle SA, British Society of Paediatric Dentistry. British Society of Paediatric Dentistry: a policy document on management of caries in the primary dentition. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010;20(Suppl 1):5.

American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Council on Clinical Affairs. Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): unique challenges and treatment option. Pediatr Dent. 2016c;38:55–6.

American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Council on Clinical Affairs. Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): unique challenges and treatment option. Pediatr Dent. 2008–2009b;30:44–6.

Kühnisch J, Ekstrand KR, Pretty I, Twetman S, van Loveren C, Gizani S, Spyridonos LM. Best clinical practice guidance for management of early caries lesions in children and young adults: an EAPD policy document. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2016;17:3–12.

Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Prevention and Management of Dental Caries in Children Dental Clinical Guidance [guidance online]. Dundee; 2018. [cited 2019 Aug 05]. Available from: http://www.sdcep.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/SDCEP-Prevention-and-Management-of-Dental-Caries-in-Children-2nd-Edition.pdf.

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Behavior guidance for the pediatric dental patient. Pediatr Dent. 2017;39:246–59.

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on perinatal and infant Oral health care. Pediatr Dent. 2016;38:150–4.

American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry – Council on Clinical Affairs. Guideline on restorative dentistry. Pediatr Dent. 2016–2017;38:250–62.

American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Clinical Affairs Committee-Restorative Dentistry Subcommittee; American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Council on Clinical Affairs. Clinical guideline on pediatric restorative dentistry. Pediatr Dent. 2008-2009;30:163–9.

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Clinical guideline on pediatric restorative dentistry. Pediatr Dent. 2004;26:106–14.

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on caries-risk assessment and management for infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Dent. 2014;36:127–34.

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on caries-risk assessment and management for infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Dent. 2013;35:E157–64.

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on caries-risk assessment and management for infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Dent. 2010-2011;32:101–8.

Massara ML, Redua P. Reference manual for clinical procedures in Pediatric Dentistry. São Paulo: Santos; 2013. Portuguese.

Massara ML, Redua P. Reference manual for clinical procedures in Pediatric Dentistry. São Paulo: Santos; 2009. Portuguese.

Ministerio de Salud. Guía Clínica Salud Oral integral para niños y niñas de 6 años. Santiago: Minsal; 2013.

Ministerio de Salud. Guía Clínica Salud Integral para niños y niñas de 6 años. Santiago: Minsal; 2008.

Uribe S. Summary guideline. Prevention and management of dental decay in the pre-school child. Evid Based Dent. 2006;7:4–7.

Periasamy K, Marsom A, Sivapragasam Y, Junid DNZ, Ibrahim N, Vengadasalam S et al. Malasia. Management of severe early childhood caries. 2012. Available in: http://www.acadmed.org.my/.

Urquhart O, Tampi MP, Pilcher L, Slayton RL, Araujo MWB, Fontana M, et al. Nonrestorative treatment for caries: systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Dent Res. 2019;98:14–26.

Elrashid AH, Alshaiji BS, Saleh SA, Zada KA, Baseer MA. Efficacy of resin infiltrate in noncavitated proximal carious lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2019;9:211–8.

Schmoeckel J, Gorseta K, Splieth CH, Juric H. How to intervene in the caries process: early childhood caries – a systematic review. Caries Res. 2020 Jan;7:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1159/000504335.

Mijan M, de Amorim RG, Leal SC, Mulder J, Oliveira L, Creugers NHJ, Frencken JE. The 3.5-year survival rates of primary molars treated according to three treatment protocols: a controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Invest. 2014;18:1061–9.

Santamaria RM, Innes NPT, Machiulskiene V, Evans DJP, Splieth CH. Caries management strategies for primary molars: 1-yr randomized control trial results. J Dent Res. 2014;93:1062–9.

van Loveren C, van Palenstein Helderman W. EAPD interim seminar and workshop in Brussels may 9 2015: non-invasive caries treatment. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2016;17:33–44.

Gao SS, Zhang S, Mei ML, Lo EC, Chu CH. Caries remineralisation and arresting effect in children by professionally applied fluoride treatment - a systematic review. BMC Oral Health. 2016;16:12.

Chibinski AC, Wambier LM, Feltrin J, Loguercio AD, Wambier DS, Reis A. Silver diamine fluoride has efficacy in controlling caries progression in primary teeth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2017;51:527–41.

Oliveira BH, Rajendra A, Veitz-Keenan A, Niederman R. The effect of silver diamine fluoride in preventing caries in the primary dentition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2019;53:24–32.

World Health Organization. Ending childhood dental caries: WHO implementation manual. [guidance online]. Geneva; 2019. [cited 2020 Mar 11]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/330643/9789240000056-eng.pdf.

Pires CW, Pedrotti D, Lenzi TL, Soares FZM, Ziegelmann PK, Rocha RO. Is there a best conventional material for restoring posterior primary teeth? A network meta-analysis. Braz Oral Res. 2018:e10. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-3107bor-2018.vol32.0010.

Santos AP, Moreira IK, Scarpelli AC, Pordeus IA, Paiva SM, Martins CC. Survival of adhesive restorations for primary molars: a systematic review and metaanalysis of clinical trials. Pediatr Dent. 2016;38:370–8.

de Amorim RG, Frencken JE, Raggio DP, Chen X, Hu X, Leal SC. Survival percentages of atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) restorations and sealants in posterior teeth: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22:2703–25.

Tedesco TK, Calvo AF, Lenzi TL, Hesse D, Guglielmi CA, Camargo LB, Gimenez T, Braga MM, Raggio DP. ART is an alternative for restoring occlusoproximal cavities in primary teeth - evidence from an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2017;27:201–9.

Klingberg G, Broberg AG. Dental fear/anxiety and dental behavior guidance problems in children and adolescents – a review of prevalence and concomitant psychological factors. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007;17:391–406.

Coulthard P, Craig D, Holden C, Robb ND, Sury M, Chopra S, Holroyd I. Current UK dental sedation practice and the ‘National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’ (NICE) guideline 112: sedation in children and young people. Br Dent J. 2015;218:E14 (era 49).

Antunes DE, Viana KA, Costa PS, Costa LR. Moderate sedation helps improve future behavior in pediatric dental patients - a prospective study. Braz Oral Res. 2016;30:e107.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Newton Fund 2016–2017 (British Council, UK and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Goias, Brazil) and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for the financial contribution to the workshop that enabled this working group.

We acknowledge the contribution of all CEDACORE (Children Experiencing Dental Anxiety: Collaboration on Research and Education) members in the discussions that underpinned this work: Alaa Bani, Aline Neves, Andrea Pintor, Anelise Daher, Avijit Banerjee, Carla Massignan, Carolina Bruzamolin, Chrysoula Tatsi, Cristiane Bendo, Daniela Raggio, Ellie Heidari, Geanina Bruj, Geovanna Machado, Heloisa Rodrigues, Jennifer Hare, Karoline Viana, Liliani Vieira, Lívia Libânio, Lucas Abreu, Luciane Costa, Marcelo Bönecker, Makbule Ogretme, Malihe Moeinian, Mariana Luca, Marie Hosey, Marília Goettems, Marina Azevedo, Mike Harrison, Mona Agel, Patrícia Corrêa-Faria, Paulo Sucasas, Paulo D’Almeida, Regina Carvalho, Renata Rocha, Sanjeev Sood, Taís Barbosa, Tatiana Fidalgo, Tim Newton and Vanessa Costa.

Funding

The researchers received scholarships from the following institutions: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq-scholarships), the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES-scholarships) and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Goiás (FAPEG-research grant). Institutions did not participate directly in the study design and data collection, analysis and interpretation stages.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PC-F, KAV, DPR, MTH and LRC contributed to the conception and design of the study, and data interpretation; PC-F, KAV contributed to the data acquisition and analysis; PC-F, KAV, DPR and LRC drafted the paper; DPR, MTH, LRC revised the paper critically for intellectual content; all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author Daniela Raggio is part of Editorial Board.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist

Additional file 2.

Characteristics of replaced studies and recommended procedures for ECC management.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Corrêa-Faria, P., Viana, K.A., Raggio, D.P. et al. Recommended procedures for the management of early childhood caries lesions – a scoping review by the Children Experiencing Dental Anxiety: Collaboration on Research and Education (CEDACORE). BMC Oral Health 20, 75 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-020-01067-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-020-01067-w