Abstract

Background

Periodontal disease is an inflammatory disease in which pathogenic infections trigger a series of inflammatory responses and redox regulation. The hypothesis of this study was that a host’s redox regulation, as modified by genetic polymorphisms, may affect periodontal disease activities (including the plaque index (PlI), bleeding on probing (BOP), and pocket depth (PD)) during periodontal therapy.

Methods

In total, 175 patients diagnosed with periodontitis were recruited from the Department of Periodontology, Taipei Medical University Hospital. Both saliva samples and clinical measurements (PlI, BOP, and PD) were taken at the baseline and at 1 month after completing treatment. Salivary manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) and catalase, and corresponding genetic polymorphisms (MnSOD, T47C, rs4880 and Catalase, C-262 T, rs1001179) were determined. The extent of change (Δ) of MnSOD or catalase was calculated by subtracting the concentration after completing treatment from that at the baseline.

Results

Subjects who carried the Catalase CC genotype had significantly higher salivary MnSOD or catalase levels. The MnSOD genotype had a significant effect on the percentage of PDs of 4~9 mm (p = 0.02), and salivary ΔMnSOD had a significant effect on the PlI (p = 0.03). The Catalase genotype had a significant effect on the PlI (p = 0.01~0.04), but the effect was not found for the mean PlI or PD. There was a significant interaction between the MnSOD genotype and salivary ΔMnSOD on PDs of 4~9 mm. After adjusting for gender, years of schooling, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, subjects with ΔMnSOD of < 0 μg/ml or Δcatalase of < 0 μg/ml had significantly higher 5.58- or 5.17-fold responses to scaling and root planing treatment.

Conclusions

The MnSOD T47C genotype interferes with the phenotype of salivary antioxidant level, alters MnSOD levels, and influences the PD recovery. MnSOD and catalase gene polymorphism associated with phenotype expression and susceptibility in periodontal root planing treatment responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease that is initiated by the accumulation of plaque biofilm and its products, with subsequent gingival bleeding, alveolar bone resorption, and periodontal pocket formation [1]. Periodontal pathogenic infections trigger a series of inflammatory responses and lead to destruction of the periodontium [2]. Several lines of clinical evidence also indicated that cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, and other chronic diseases may contribute to periodontal inflammation, and the symptoms of systemic diseases can also be mitigated by preventing periodontal disease [3, 4].

The excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) causes progressive oxidative damage via responses to periodontal injury and inflammation [5,6,7]. ROS, such as superoxide and hydroxyl species, are regulated by the thioredoxin system to transduce redox signals and alter activities of antioxidant enzymes to eliminate free radicals. Superoxide radicals (O2•-) are catalyzed into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by superoxide dismutase (SOD). H2O2 is then converted into H2O and O2 by catalase. In the decomposition of H2O2, hydroxyl radicals (OH•) formed by splitting O-O bonds can cause DNA and protein damage [8,9,10]. Salivary antioxidant activities, such as the total oxidant status, catalase, and SOD, have been useful biomarkers for evaluating the severity of periodontal disease and treatment effectiveness [11, 12].

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) contribute to expressions of genetic susceptibility to inflammatory and redox reactions in individuals with periodontitis [13]. The genotype (SNPs) and phenotype (gene expressions) of periodontal tissues can be used to evaluate susceptibility to periodontal disease and may also contribute to the effectiveness of clinical treatments.

A polymorphism of the manganese SOD (MnSOD) gene (T47C, rs4880) affects the redox status balance through altering enzyme localization and mitochondrial transportation, and the MnSOD T47C SNP is also controlled by environmental factors [14]. A polymorphism of the Catalase gene (C-262 T, rs1001179) is located in the promoter region, and it has a functional impact on catalase expression [15]. Activities of MnSOD and catalase differ due to allelic frequencies which account for ethnic variations. Frequencies of MnSOD T47 and Catalase C-262 respectively range 23%~ 29 and 61%~ 69% in Caucasians and 66%~ 75 and 90%~ 93% in Asians [16,17,18,19]. Both of these polymorphic variants can alter enzymatic activities against oxidative damage and modulate individual susceptibility to disease occurrence. It was also shown that genetic polymorphisms of these antioxidants were associated with promoting antioxidative effects against the risks of cancer and tumorigenesis [18, 19].

The goal of periodontal treatment is to recover periodontal health and function, maintain esthetics of the dentition, and achieve effective infection control [20]. However, limited treatment effectiveness related to redox homeostasis and individual susceptibility has seldom been reported. The hypothesis is that a host’s inflammatory response, as modified by genetic polymorphisms and salivary antioxidant levels, can affect the effectiveness of periodontal treatment. The objective of this study was to explore associations of genetic polymorphisms and salivary expressions of MnSOD and catalase with the effectiveness of periodontal disease treatment.

Materials and methods

Subject recruitment

Participants were enrolled from the Division of Prosthodontics, Department of Dentistry at Taipei Medical University (TMU) Hospital between July 2013 and April 2016. Subjects who were eligible for a comprehensive periodontal treatment project (CTPT) were recruited. The CTPT is a National Health Insurance program to reduce periodontal disease in Taiwan [21]. Subjects who met all of the following criteria were included in this study: the patient had been diagnosed with ICD-9523, this was their first visit for periodontitis treatment, the number of functional teeth was > 15, the probing depth was ≥5 mm for at least six teeth, and the patient had not been treated with non-surgical therapy. Patients who had received periodontal therapy, were pregnant, or had been diagnosed with cancer were excluded from the study. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the TMU Joint Institutional Review Board (Taipei, Taiwan), and complied with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

All participants provided written informed consent before the questionnaire interview and salivary specimen collection. A previous epidemiological study showed that factors such as age, gender, educational level, and tobacco and alcohol use were risk factors for periodontal disease [3]. Before periodontal treatment, each participant completed a structured questionnaire that collected sociodemographic characteristics (gender and years of schooling), lifestyle factors (cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and betel nut chewing), personal and family disease histories, and oral hygiene knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. According previous study [22], the smoking status was defined as “current smokers” (who smoked more than 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime and currently smokes cigarettes), “former smokers” (who have smoked more than 100 cigarettes in the pasts and currently not smoking), and “never smokers” (who had never smoked in their lifetime). Alcohol consumption was defined as current (drinks alcoholic beverages more than 3 times per week), former (stopped drinking alcoholic beverages for ≥1 year or has occasionally drunk alcoholic beverages in their lifetime), and never (has not drunk alcoholic beverages in their lifetime).

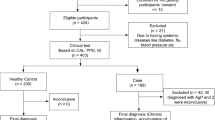

Figure 1 is a flowchart of participant enrollment. After patients had completed the informed consent form, 209 patients were invited to participate in this study by convenience sampling. The structured questionnaire included demographics, socioeconomic status, cigarette smoking status (quantity, duration, and pack-years), alcohol consumption, and frequency of betel nut chewing and was carried out by well-trained interviewers. A previous study indicated that it is better to treat periodontitis for a period of time (e.g., once a week continuously for 1 month, as demonstrated in our current study). The advantages of this strategy may include: (1) patients feel less stressful during the stable therapeutic process; (2) oral hygiene can be further improved by increasing the number of treatments; and (3) patients can even establish or enhance their reliance on these regular therapeutic procedures [23]. In the present study, all patients completed the therapeutic process within 4 weeks. The therapeutic efficacy of periodontitis was evaluated 1 week after treatment by measuring data collected from healing samples. After excluding those with incomplete data on clinical parameters or genotype, there were 175 patients who completed scaling and root planing.

The sample size estimation was based on the paper published by Novakovic et al. [24]. The value of the means of salivary SOD before and after the treatment of scaling and root planing were counted to be 0.45 and 0.39, respectively. G*Power software (version 3.1.9.4) and program of “Means: Difference between 2 dependent means (matched/paired samples t-test)” was used to calculate the sample size [25]. The correlation of salivary SOD before and after the treatment was not showed in the previous study, so here we assumed the correlation as 0.1 and 0.5, respectively. Under the correlation of 0.1 and 0.5, the effect size from the mean difference (0.06) was 0.24 and 0.30, respectively. With the statistical power of 0.8, alpha of 0.05, two tails with an effect size of 0.30 and 0.24, the required sample size was therefore calculated to be 89 to 136 pairs, respectively.

Specimen collection

Saliva samples were collected at the baseline (before the non-surgical intervention) and at 1 week after completing clinical treatment. Participants were asked to chew a piece of wax for 5 min to collect saliva using the Saliva-Check kit (GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Oral swab specimens were also collected. Subjects rinsed their mouth with water to remove food residue and waited at least 10 min after rinsing to avoid specimen dilution before saliva collection. After collection, saliva and oral swab samples were stored in an ice bucket and immediately transported to the laboratory. Saliva samples were mixed with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) at a ratio of 1 ml saliva: 10 μL protease inhibitor cocktail and centrifuged (3000 rpm) for 3 min at room temperature. Supernatants were collected and stored at − 20 °C until analysis. Saliva samples were analyzed for oxidative stress biomarkers.

Salivary antioxidants determination

MnSOD and catalase levels were determined by an immunoassay using the MILLIPLEX® MAP Human Oxidative Stress Magnetic Bead Panel kit (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Each sample (35 μL) diluted to an identical quantity of protein with assay buffer was added to a 96-well plate, mixed with 35 μL of assay buffer and 25 μL of antibody-immobilized beads, and incubated 2 h at room temperature, followed by the addition of detection antibodies (50 μL) and streptavidin phycoerythrin (50 μL) incubation. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was determined. The R2 value for the standard curve was > 0.995. Coefficients of variance (CVs) for the intra-assay ranged 3.49%~ 8.10%, and CVs for the inter-assay ranged 1.22%~ 12.30%. A laboratory negative control was not included in the manufacturer’s instructions of MILLIPLEX® MAP Human Oxidative Stress Magnetic Bead Panel kit. The extent of change (Δ) of MnSOD or catalase was calculated by subtracting the concentration after completing treatment from that at the baseline.

Determination of MnSOD and catalase genetic polymorphisms

Genomic DNA was extracted from mouth swabs by a QIAamp DNA Investigator Kit in accordance with the manufacturer’s instruction (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). MnSOD T47C and Catalase C-262 T were genotyped by a polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) method modified from earlier studies [15, 26]. Genetic polymorphisms of MnSOD (a substitution of the T47C polymorphic site located on chromosome 6 q 25) and Catalase (a substitution of the C-262 T polymorphic site located on chromosome 11 p 13) were determined by the PCR-RFLP method. MnSOD primers were 5′-GCACCAGCAGGCAGCTGGCGCCGG-3′ and 5′-TGCGCGTTGATGTGAGGTTCCAG-3′. Catalase primers were 5′-AGAGCCTCGCCCCGCCGGACCG-3′ and 5′-TGCGCGTTGATGTGAGGTTCCAG-3′. Initial denaturation was set to 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 57 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. A final extension was prolonged for 5 min. DNA fragments were amplified with restriction endonucleases, visualized through 3% agarose gel electrophoresis, stained, and photographed under UV light. Wild-type (TT) MnSOD was characterized as a 112-bp fragment, while the mutant types (TC and CC) were 90- and 22-bp fragments, respectively. Two fragments of 155 and 30 bp were characterized as the wild-type (CC) of Catalase and a 185-bp fragment as the mutant type (CT or TT). The validity of genotyping was determined by the Hardy-Weinberg Law and DNA sequencing. Around 25% of the samples were genotyped in duplicate for these two SNPs, and the concordance rate was 100%.

A previous study showed that subjects carrying the less-common T allele (CT and TT) of catalase had significantly higher catalase activity compared to that of CC homozygotes [15]. Sutton et al. demonstrated that the less-common C allele (TC and TT) of MnSOD had significantly higher messenger (m)RNA expression compared to TT homozygotes [27]. The less-common allele of these two genes was related to higher expression. According to the function of the genotype, genotypes of MnSOD were classified as TT and TC/CC, and those of catalase were classified as CC and CT/TT.

Clinical parameters and treatment evaluation

Clinical examinations and non-surgical periodontal treatments, such as subgingival scaling, root planing, and oral hygiene instructions, were carried out. In order to reduce inter- and intra-variations of clinical parametric assessments, all clinical parametric assessments were performed by the same periodontist. The periodontist followed examiner alignment and assessment in periodontal research published by Hefti and Preshaw [28], to perform all clinical parametric assessments in this study.

Measurement of the plaque index (PlI) was based on both soft debris and mineralized deposits on four surfaces (buccal, lingual, mesial, and distal) of a tooth, and the presence or absence of plaque was recorded at all sites. The PlI was calculated by dividing the number of plaque-containing surfaces by the total number of available surfaces [29]. The bleeding on probing (BOP) and pocket depth (PD) were measured using a periodontal probe (Color Coded Michigan Williams Dental Probe) at six sites (distobuccal, buccal, mesiobuccal, distolingual, lingual, and mesiolingual) on each tooth. The BOP and PD were expressed as a percentage, which was calculated by dividing the number of bleeding sites or sites with PDs by the total number of available sites. The average periodontal PD (PD mean) was also calculated as an index of clinical parameters.

Studies have thus far not identified a level of plaque infection compatible with maintenance of periodontal health. However, in a clinical setup, a plaque control record of 20%~ 40% might be tolerated by most patients. It is important to realize that the full-mouth plaque score has to be related to the host response of the patient, in other words compared to inflammatory parameters [30]. According to a previous study, periodontal pockets deeper than 4.2 mm were associated with periodontal attachment gain after periodontal surgery [31]. As modified from two previous studies, participants were classified into responsive and non-responsive groups according to the clinical indices. The non-responsive group was defined if the PlI exceeded 30% and PD mean exceeded 3 mm after treatment. The opposite defined the responsive group.

Statistical analysis

The SAS program vers. 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. A multiple general linear regression analysis was used to determine contributions of demographic characteristics (independent variables) to periodontal clinical parameters (dependent variables) (Table 1). Independent variables in Table 1 were recorded as follows: gender (male was recorded as (1), female was recorded as (0)), years of schooling (> 12 years was recorded as (1), ≤12 years was recorded as (0)), smoking status (current and former smoker was recorded as (1), never having smoked was recorded as (0)), and alcohol consumption (current and former consumer was recorded as (1), never consumed was recorded as (0)). Differences in periodontal clinical parameters, in salivary antioxidant levels, and among the genotypes of antioxidants were determined using Student‘s t-test (Table 2). Differences in salivary antioxidant levels at the baseline and after treatment were evaluated with a paired t-test (Fig. 2).

To further explore interactions of salivary antioxidant levels and genotypes with periodontal clinical parameters, a two-way repeated-measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare subject performance according to the clinical parameters before and after treatment, using differences in genotypes and salivary antioxidant levels as the main effects (independent variables). The effect of genotype was classified into two levels (TT and TC/CC for MnSOD and CC CT/TT for Catalase). The effect on differences in salivary antioxidant levels was a continuous variable.

Univariate and multiple logistic regressions were used to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) of scaling root planing responses to genotypes and phenotypes of antioxidants (Table 4). The effects of salivary ΔMnSOD and Δcatalase were classified into two levels (≥0 and < 0 μg/ml), If the change of the antioxidants was less than 0 μg/ml, it means that the level of the antioxidants was increased during treatment. Nevertheless, if the change of the antioxidants was greater than 0 μg/ml, than it means that the level of the antioxidants was decreased during treatment. The adjusted potential confounders as independent variables (gender, years of schooling, smoking status, and alcohol consumption) in the multiple logistic regression models were the same as those in Table 1. The level of significance was set to p < 0.05 for all statistical tests.

Results

Among 175 participants, consisting of 80 males and 95 females, the average age was 55.55 years. More than half (57.06%) of participants had a bachelor’s degree. The baseline BOP percentage and PDs of 4~9 mm in subjects who had > 12 school years were significantly lower than those of subjects who had ≤9 years of school (p < 0.01 and p = 0.02). The majority of subjects did not smoke or drink alcohol. There were no significant differences in percentages of the baseline/after treatment for the PlI, BOP, or PD in groups stratified be sex, smoking status, and alcohol consumption (Additional file 1: Table S1). Table 1 shows results of multiple general linear regressions of demographic characteristics on periodontitis clinical parameters in patients with periodontal disease. No demographic characteristics were associated with the baseline PlI or PD mean. After adjusting for gender, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, baseline percentages of BOP and PD of 4~9 mm were significantly associated with years of schooling. Compared to subjects who had ≤12 years of schooling, subjects who had > 12 years of schooling had significantly lower baseline percentages of BOP (8.66%, p < 0.01) and PD of 4~9 mm (4.43, p < 0.05). The regression coefficients of the baseline BOP decreased after adjusting for gender, smoking status, and alcohol consumption. The baseline BOP in current smokers and those who had quit smoking was significantly 9.55% lower than that of non-smokers (p < 0.05). No demographic characteristics were associated with any periodontal clinical parameters after treatment.

Table 2 shows distributions of periodontitis clinical parameters and salivary MnSOD and catalase levels among the subgroups of MnSOD and Catalase genotypes. There were no significant differences in baseline clinical parameters between MnSOD genotype strata. Subjects who carried the Catalase CC genotype had significant higher salivary levels of MnSOD and catalase than did subjects who carried the Catalase CT/TT genotype (p = 0.02 and p < 0.01, respectively). ΔMnSOD and ΔCatalase were significant higher in subjects who carried the Catalase CC genotype than those with the Catalase CT/TT genotype (p < 0.01 and p = 0.02, respectively).

Figure 2 shows differences in salivary antioxidant levels at the baseline and after treatment completion. A significant reduction in the MnSOD level after treatment was found in subjects who carried the MnSOD TT, MnSOD TC/CC, or Catalase CC genotype (Fig. 2a). A significant reduction in the catalase level after treatment was found in subjects who carried the MnSOD TT, MnSOD TC/CC, or Catalase CC genotype (Fig. 2b).

A repeated-measures ANOVA was used to calculate the adjusted percentage changes in PlI, BOP, and PD of 4~9 mm for the combined effect of genotype and differences in salivary oxidative levels (Table 3). Salivary ΔMnSOD had a significant effect on the PlI (p = 0.03). When adjusted for the MnSOD genotype, PlI changes decreased by 0.43% with an increase of 1 μg/ml in ΔMnSOD. When adjusted for the ΔMnSOD level, the MnSOD genotype had a significant effect on the percentage of PDs of 4~9 mm (p = 0.02). The decrease in the percentage of PDs of 4~9 mm in subjects who carried the MnSOD CC genotype was 2.82% significantly lower than those in subjects with the MnSOD CT/TT genotype (16.97% vs. 19.79%). There was a significant interaction between the MnSOD genotype and ΔMnSOD in those with PDs of 4~9 mm (p < 0.01), when adjusting for the ΔMnSOD level, as that of subjects who carried the MnSOD CC genotypes was 4.23% significantly lower than that in subjects with the MnSOD CT/TT genotype. There was no significant interaction between the MnSOD genotype and Δcatalase in terms of clinical parameters. When adjusting for the ΔMnSOD level or Δcatalase level, the Catalase genotype had a significant effect on the PlI. When adjusting for the ΔMnSOD level or Δcatalase level, the decrease in the percentage of PlI in subjects who carried the Catalase CC genotype was 13.84% (p = 0.04) or 17.70% (p = 0.01) significantly higher than those of subjects who carried the Catalase CT/TT genotype, respectively. The effect was not found in the mean change in percentage of PlI or PDs of 4~9 mm between Catalase CC genotypes and the salivary ΔMnSOD level or Δcatalase level. Finally, there was no significant interaction between the Catalase genotype and ΔMnSOD or Δcatalase on clinical parameters.

Table 4 shows ORs of scaling and root planing treatment response in genotypes and phenotypes of antioxidants. In the univariate logistic regression model, a significant association was observed between salivary antioxidant changes and responses to scaling and root planing treatments. Compared to subjects who had ΔMnSOD of ≥0 μg/ml, subjects who had ΔMnSOD of < 0 μg/ml had a significantly higher 4.86-fold response to scaling and root planing treatment. Compared to subjects who had Δcatalase of ≥0 μg/ml, subjects who had Δcatalase of < 0 μg/ml had a significantly higher 5.03-fold response to scaling and root planing treatment. After adjusting for gender, years of schooling, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, subjects with ΔMnSOD of < 0 μg/ml or Δcatalase of < 0 μg/ml had a significantly higher 5.58- or 5.17-fold response to scaling and root planing treatment. Salivary antioxidants of subjects increased during treatment to increase the treatment response.

Discussion

In this study, salivary MnSOD and catalase were significantly reduced after treatment, and an interaction between the genotype and phenotype of MnSOD was observed in the PD treatment effect. Saliva that contains unique information on oral physiological changes can be a useful diagnostic tool for periodontal diseases. Specific oxidative stress biomarkers, such as lipid peroxidation levels, the total oxidant status, and antioxidant levels, can reflect the severity of periodontal disease and treatment effectiveness [32,33,34,35]. A recent study mentioned that SOD was correlated with inflammatory diseases and could reflect the onset of disease [36]. An increase in antioxidant activity was accompanied by an early inflammatory syndrome, while its alleviation occurred in response to pathological progression. Novakovic et al. found that patients with periodontitis had higher antioxidant levels compared to periodontally healthy subjects, and antioxidant levels were significantly alleviated after non-surgical treatment [24]. Our previous study also demonstrated that an increase in SOD was related to the severity of periodontitis and to oral health behaviors [37]. Results of this study were consistent with those previous studies mentioned above; salivary MnSOD was associated with PlI changes. The importance of salivary antioxidants as prognostic biomarkers of periodontal treatment should be addressed.

Polymorphisms of antioxidants can modulate genetic activity and formation of antioxidants. In vitro, the alanine allele (MnSOD TC/CC) increased the activity of the MnSOD homotetramer and produced more-efficient import of MnSOD into the mitochondrial matrix compared to the valine allele (MnSOD TT) [38]. The high transcriptional activity of Catalase T variants was determined in HepG2 and K562 cells. Individuals who carried the Catalase T allele had higher catalase levels compared to those who carried the C allele [15]. Nevertheless, there were no significant differences in MnSOD or catalase activities regardless of the genotype in this study. Hong et al. also found similar results [39]. In addition, genetic polymorphisms have been associated with the susceptibility to disease occurrence and development. Kakkoura et al. indicated that wild-type alleles of MnSOD and Catalase SNPs may promote antioxidative effects of the Mediterranean diet against breast cancer risk [19]. In this study, the significant association between genetic variations and periodontal treatment existed in the MnSOD and Catalase genotypes, but there was no interaction between genotype and phenotype. Further studies are needed to explore relationships among genetic polymorphisms, enzymatic activities, and therapeutic responses.

Oral health is recognized as an essential and integral component of one’s general health and well-being; a major concern is the high prevalence of periodontal disease worldwide [40, 41]. The United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) showed that the periodontal disease prevalence in adults aged ≥30 years had decreased from 47.2% (NHANES 2009–2010) to 44.8% (NHANES 2011–2012) [42, 43]. In Taiwan, it was estimated that approximately 54% of adults aged 35~44 years have mild to severe periodontitis [44]. The prevalence of periodontal disease has significantly increased in Taiwan over the past 17 years [45]. Compared to other countries, such as India (72%), Italy (35%~ 40%), and the US (46%), it is noteworthy that there is a higher prevalence of periodontitis in Taiwan [46,47,48].

Periodontal disease results from periodontal pathogenic infections that induce a series of inflammatory and redox responses that lead to destruction of periodontal tissues and even tooth loss [7]. Non-surgical periodontal treatments, such as scaling and root planing, are the primary and initial steps for cleaning root surfaces and removing plaque and calculus from deep periodontal pockets; these are simultaneously used in coordination with oral hygiene instructions and ongoing maintenance of oral health behaviors [37]. The goals of periodontal treatment are to recover the periodontal health and function, maintain esthetics of the dentition, and achieve effective infection control and periodontal tissue regeneration [20]. In general, the majority of participants exhibit good responses to non-surgical periodontal treatments. Compared to other studies in terms of periodontal disease activities, reductions in the PlI, BOP, and PD in this study were clinically acceptable [49,50,51]. However, around 10% of patients still had increased PlI, BOP, and PD after treatment, and the results showed that oxidative stress played an important role during periodontal treatment.

Smoking is an important environmental risk factor for periodontal disease. Free radicals generated by cigarette smoke affect antioxidant systems in the body [7, 24, 52]. Cigarette smoke may interfere with inflammatory defense mechanisms of periodontal tissues and inhibit functions against plaque bacteria, thus reducing the effectiveness of periodontal treatment [53]. In the US NHANES, 41.9% of adult periodontitis cases were attributable to current cigarette smoking and 10.9% to former smoking [54]. Previous studies indicated that smokers exhibit less improvement than nonsmokers following non-surgical periodontal treatment [49, 55]. Preshaw et al. indicated that non-smokers tend to have less-advanced periodontitis at the baseline and better responses to non-surgical periodontal treatment [56]. Smokers had a higher percentage of PDs of 4~9 mm in this study.

Effective plaque control is the most important step in preventing dental caries and periodontal diseases [57,58,59,60]. Risk factors for periodontal disease, including age, gender, education, an unhealthy diet, tobacco use, alcohol use, dental care, etc., have been studied in epidemiological research [3, 61]. In spite of significant associations among antioxidants, genetic polymorphisms, and periodontal treatments, there is no denying that patients with poor responses to treatment have inferior health statuses, and this may have biased the results. In addition, the small sample size derived from low allelic frequency is a major limitation of this study. The less-frequent variant of the catalase gene in this study was similar to that in other Asian countries, such as Korea and China [62, 63]. Other factors, including dietary intake, the nutritional status, and dental care, that were not accurately measured in this study need to be further accounted for in future studies.

Conclusions

The MnSOD T47C genotype interferes with the phenotype of salivary antioxidant level, alters MnSOD levels, and influences the recovery percentage of PDs of 4~9 mm. MnSOD and catalase gene polymorphism associated with phenotype expression and susceptibility in periodontal root planing treatment responses.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used during the study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- BOP:

-

Bleeding on probing

- CTPT:

-

Comprehensive periodontal treatment project

- MnSOD:

-

Manganese superoxide dismutase

- PD:

-

Pocket depth

- PlI:

-

Plaque index

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SNP:

-

Single-nucleotide polymorphism

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

References

Williams RC. Periodontal disease. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(6):373–82.

Hernandez M, Dutzan N, Garcia-Sesnich J, Abusleme L, Dezerega A, Silva N, Gonzalez FE, Vernal R, Sorsa T, Gamonal J. Host-pathogen interactions in progressive chronic periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2011;90(10):1164–70.

Petersen PE, Ogawa H. The global burden of periodontal disease: towards integration with chronic disease prevention and control. Periodontol. 2012;60(1):15–39.

Inaba H, Amano A. Roles of oral bacteria in cardiovascular diseases--from molecular mechanisms to clinical cases: implication of periodontal diseases in development of systemic diseases. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010;113(2):103–9.

Sculley DV, Langley-Evans SC. Salivary antioxidants and periodontal disease status. Proc Nutr Soc. 2002;61(1):137–43.

Kanzaki H, Wada S, Narimiya T, Yamaguchi Y, Katsumata Y, Itohiya K, Fukaya S, Miyamoto Y, Nakamura Y. Pathways that regulate ROS scavenging enzymes, and their role in defense against tissue destruction in periodontitis. Front Physiol. 2017;8:351.

D'Aiuto F, Nibali L, Parkar M, Patel K, Suvan J, Donos N. Oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and severe periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2010;89(11):1241–6.

Netto LE, Antunes F. The roles of Peroxiredoxin and Thioredoxin in hydrogen peroxide sensing and in signal transduction. Mol Cells. 2016;39(1):65–71.

Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(1):47–95.

Sies H. Oxidative stress: oxidants and antioxidants. Exp Physiol. 1997;82(2):291–5.

Tothova L, Kamodyova N, Cervenka T, Celec P. Salivary markers of oxidative stress in oral diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2015;5:73.

Tothova L, Celec P. Oxidative stress and antioxidants in the diagnosis and therapy of periodontitis. Front Physiol. 2017;8:1055.

Dosseva-Panova, V.; Mlachkova, A.; Popova, C., Gene polymorphisms in periodontitis. Overview. In Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment, Taylor & Francis: 2015; Vol. 29, pp 834–839.

Bresciani G, Cruz IB, de Paz JA, Cuevas MJ, Gonzalez-Gallego J. The MnSOD Ala16Val SNP: relevance to human diseases and interaction with environmental factors. Free Radic Res. 2013;47(10):781–92.

Forsberg L, Lyrenas L, de Faire U, Morgenstern R. A common functional C-T substitution polymorphism in the promoter region of the human catalase gene influences transcription factor binding, reporter gene transcription and is correlated to blood catalase levels. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30(5):500–5.

Ahn J, Nowell S, McCann SE, Yu J, Carter L, Lang NP, Kadlubar FF, Ratnasinghe LD, Ambrosone CB. Associations between catalase phenotype and genotype: modification by epidemiologic factors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15(6):1217–22.

Mak JC, Leung HC, Ho SP, Ko FW, Cheung AH, Ip MS, Chan-Yeung MM. Polymorphisms in manganese superoxide dismutase and catalase genes: functional study in Hong Kong Chinese asthma patients. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36(4):440–7.

Shen Y, Li D, Tian P, Shen K, Zhu J, Feng M, Wan C, Yang T, Chen L, Wen F. The catalase C-262T gene polymorphism and cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(13):e679.

Kakkoura MG, Demetriou CA, Loizidou MA, Loucaides G, Neophytou I, Malas S, Kyriacou K, Hadjisavvas A. MnSOD and CAT polymorphisms modulate the effect of the Mediterranean diet on breast cancer risk among Greek-Cypriot women. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55(4):1535–44.

Caffesse RG, Mota LF, Morrison EC. The rationale for periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000. 1995;9:7–13.

Chan CL, You HJ, Lian HJ, Huang CH. Patients receiving comprehensive periodontal treatment have better clinical outcomes than patients receiving conventional periodontal treatment. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115(3):152–62.

Eke PI, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO, Borrell LN, Borgnakke WS, Dye B, Genco RJ. Risk indicators for periodontitis in US adults: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol. 2016;87(10):1174–85.

Barteczko I; Eberhard J, Full-mouth Disinfection vs. Scaling and Root Planing for the Treatment of Periodontitis: A review of the current literature. Perio : periodontal practice today 2004.

Novakovic N, Todorovic T, Rakic M, Milinkovic I, Dozic I, Jankovic S, Aleksic Z, Cakic S. Salivary antioxidants as periodontal biomarkers in evaluation of tissue status and treatment outcome. J Periodontal Res. 2014;49(1):129–36.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–91.

Lin P, Hsueh YM, Ko JL, Liang YF, Tsai KJ, Chen CY. Analysis of NQO1, GSTP1, and MnSOD genetic polymorphisms on lung cancer risk in Taiwan. Lung Cancer. 2003;40(2):123–9.

Sutton A, Imbert A, Igoudjil A, Descatoire V, Cazanave S, Pessayre D, Degoul F. The manganese superoxide dismutase Ala16Val dimorphism modulates both mitochondrial import and mRNA stability. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15(5):311–9.

Hefti AF, Preshaw PM. Examiner alignment and assessment in clinical periodontal research. Periodontol. 2012;59(1):41–60.

O'Leary TJ, Drake RB, Naylor JE. The plaque control record. J Periodontol. 1972;43(1):38.

Lindhe, J.; Lang, N. P.; Karring, T., Clinical periodontology and implant dentistry. Wiley: 2009.

Lindhe J, Socransky SS, Nyman S, Haffajee A, Westfelt E. "critical probing depths" in periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1982;9(4):323–36.

Kim SC, Kim OS, Kim OJ, Kim YJ, Chung HJ. Antioxidant profile of whole saliva after scaling and root planing in periodontal disease. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2010;40(4):164–71.

Prior RL, Cao G. In vivo total antioxidant capacity: comparison of different analytical methods. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;27(11–12):1173–81.

Moore S, Calder KA, Miller NJ, Rice-Evans CA. Antioxidant activity of saliva and periodontal disease. Free Radic Res. 1994;21(6):417–25.

Day BJ. Antioxidant therapeutics: Pandora's box. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;66:58–64.

McCord JM, Edeas MA. SOD, oxidative stress and human pathologies: a brief history and a future vision. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005;59(4):139–42.

Yang PS, Huang WC, Chen SY, Chen CH, Lee CY, Lin CT, Huang YK. Scaling-stimulated salivary antioxidant changes and oral-health behavior in an evaluation of periodontal treatment outcomes. Sci World J. 2014;2014:814671.

Sutton A, Khoury H, Prip-Buus C, Cepanec C, Pessayre D, Degoul F. The Ala16Val genetic dimorphism modulates the import of human manganese superoxide dismutase into rat liver mitochondria. Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13:145–57.

Kim JH, Gil HW, Yang JO, Lee EY, Hong SY. Effect of glutathione administration on serum levels of reactive oxygen metabolites in patients with paraquat intoxication: a pilot study. Korean J Intern Med. 2010;25(3):282–7.

Petersen PE. The world Oral health report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century--the approach of the WHO global Oral health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(Suppl 1):3–23.

Petersen PE. World Health Organization global policy for improvement of oral health--world health assembly 2007. Int Dent J. 2008;58(3):115–21.

Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO, Genco RJ. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res. 2012;91(10):914–20.

Eke PI, Zhang X, Lu H, Wei L, Thornton-Evans G, Greenlund KJ, Holt JB, Croft JB. Predicting periodontitis at state and local levels in the United States. J Dent Res. 2016;95(5):515–22.

Department of Health, T, Bureau of Health Promotion Annual Report, 2015. 2015.

Yu HC, Su NY, Huang JY, Lee SS, Chang YC. Trends in the prevalence of periodontitis in Taiwan from 1997 to 2013: a nationwide population-based retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(45):e8585.

Aimetti M, Perotto S, Castiglione A, Mariani GM, Ferrarotti F, Romano F. Prevalence of periodontitis in an adult population from an urban area in North Italy: findings from a cross-sectional population-based epidemiological survey. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42(7):622–31.

Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Slade GD, Thornton-Evans GO, Borgnakke WS, Taylor GW, Page RC, Beck JD, Genco RJ. Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol. 2015;86(5):611–22.

Peter KP, Mute BR, Pitale UM, Shetty S, Hc S, Satpute PS. Prevalence of periodontal disease and characterization of its extent and severity in an adult population - an observational study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(12):ZC04–7.

Hughes FJ, Syed M, Koshy B, Marinho V, Bostanci N, McKay IJ, Curtis MA, Croucher RE, Marcenes W. Prognostic factors in the treatment of generalized aggressive periodontitis: I. clinical features and initial outcome. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33(9):663–70.

Knofler GU, Purschwitz RE, Jentsch HF. Clinical evaluation of partial- and full-mouth scaling in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78(11):2135–42.

Stenman J, Lundgren J, Wennstrom JL, Ericsson JS, Abrahamsson KH. A single session of motivational interviewing as an additive means to improve adherence in periodontal infection control: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39(10):947–54.

Celecova V, Kamodyova N, Tothova L, Kudela M, Celec P. Salivary markers of oxidative stress are related to age and oral health in adult non-smokers. J Oral Pathol Med. 2013;42(3):263–6.

Preshaw PM, Seymour RA, Heasman PA. Current concepts in periodontal pathogenesis. Dent Update. 2004;31(10):570–8.

Tomar SL, Asma S. Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: findings from NHANES III. J Periodontol. 2000;71(5):743–51.

Bergstrom J, Bostrom L. Tobacco smoking and periodontal hemorrhagic responsiveness. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28(7):680–5.

Preshaw PM, Holliday R, Law H, Heasman PA. Outcomes of non-surgical periodontal treatment by dental hygienists in training: impact of site- and patient-level factors. Int J Dent Hyg. 2013;11(4):273–9.

Aspiras, M.; Stoodley, P.; Nistico, L.; Longwell, M.; de Jager, M., Clinical implications of power toothbrushing on fluoride delivery: effects on biofilm plaque metabolism and physiology. Int J Dent 2010, 2010, 651869.

Armitage GC, Robertson PB. The biology, prevention, diagnosis and treatment of periodontal diseases: scientific advances in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140(suppl_1):36S–43S.

Ling LJ, Hung SL, Tseng SC, Chen YT, Chi LY, Wu KM, Lai YL. Association between betel quid chewing, periodontal status and periodontal pathogens. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2001;16(6):364–9.

Neely AL, Holford TR, Loe H, Anerud A, Boysen H. The natural history of periodontal disease in man. Risk factors for progression of attachment loss in individuals receiving no oral health care. J Periodontol. 2001;72(8):1006–15.

Genco RJ, Borgnakke WS. Risk factors for periodontal disease. Periodontol. 2013;62(1):59–94.

El-Sohemy A, Cornelis MC, Park YW, Bae SC. Catalase and PPARgamma2 genotype and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in Koreans. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26(5):388–92.

Yeh HL, Kuo LT, Sung FC, Yeh CC. Association between Polymorphisms of Antioxidant Gene (MnSOD, CAT, and GPx1) and Risk of Coronary Artery Disease. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018:8.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from Taipei Medical University Hospital (104TMU-TMUH-21 and 106TMU-TMUH-25), the National Science Council (NSC102–2314-B-038-019), and Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST105–2314-B-038-045, MOST106–2314-B-038-018 and MOST108–2314-B-038-092).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YK conceived and designed this work. CH and WT performed the experiments. YK, CH and NC analyzed the data. YK contributed reagents, materials, or analytical tools. CY recruited study subjects. YK, CY, and CH wrote the manuscript. NC and HM partly contributed to the conception and design of the work and recruited study subjects. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript and ensure this is the case.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent before the questionnaire interview. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Taipei Medical University Joint Institutional Review Board, Taipei, Taiwan, and complied with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Demographic characteristics and periodontitis clinical parameter of patients. (DOC 70 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, CY., Chang, CH., Teng, NC. et al. Associations between the phenotype and genotype of MnSOD and catalase in periodontal disease. BMC Oral Health 19, 201 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0877-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0877-3