Abstract

Background

Although obesity, defined by body mass index (BMI), has been associated with a higher risk of hospitalisation and more severe course of illness in Covid-19 positive patients amongst the British population, it is unclear if this translates into increased mortality. Furthermore, given that BMI is an insensitive indicator of adiposity, the effect of adipose volume on Covid-19 outcomes is also unknown.

Methods

We used the UK Biobank repository, which contains clinical and anthropometric data and is linked to Public Health England Covid-19 healthcare records, to address our research question. We performed age- and sex- adjusted logistic regression and Chi-squared test to compute the odds for Covid-19-related mortality as a consequence of increasing BMI, and other more sensitive indices of adiposity such as waist:hip ratio (WHR) and percent body fat, as well as concomitant cardiometabolic illness.

Results

13,502 participants were tested for Covid-19 (mean age 70 ± 8 years, 48.9% male). 1582 tested positive (mean age 68 ± 9 years, 52.8% male), of which 305 died (mean age 75 ± 6 years, 65.5% male). Increasing adiposity was associated with higher odds for Covid-19-related mortality. For every unit increase in BMI, WHR and body fat, the odds of death amongst Covid19-positive participants increased by 1.04 (95% CI 1.01–1.07), 10.71 (95% CI 1.57–73.06) and 1.03 (95% CI 1.01–1.05), respectively (all p < 0.05). Referenced to Covid-19 positive participants with a normal weight (BMI 18.5–25 kg/m2), Covid-19 positive participants with BMI > 35 kg/m2 had significantly higher odds of Covid-19-related death (OR 1.70, 95% CI 1.06–2.74, p < 0.05). Covid-19-positive participants with metabolic (diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia) or cardiovascular morbidity (atrial fibrillation, angina) also had higher odds of death.

Conclusions

Anthropometric indices that are more sensitive to adipose volume and its distribution than BMI, as well as concurrent cardiometabolic illness, are associated with higher odds of Covid-19-related mortality amongst the UK Biobank cohort that tested positive for the infection. These results suggest adipose volume may contribute to adverse Covid-19-related outcomes associated with obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As of 28 August 2020, the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic resulted in over 24 million confirmed cases and 827,000 deaths worldwide [1], of which over 330,000 and 41,000 were in the UK [2], respectively. With accumulating global experience, risk factors for Covid-19 infection and predictors of outcomes are becoming increasingly recognised. Amongst these, a body mass index (BMI) within the overweight (25-30 kg/m2) or obese (> 30 kg/m2) categories and cardiometabolic morbidity have been associated with a more serious illness that necessitate hospitalisation and invasive ventilation [3,4,5,6]. Whether these risk factors also translate into higher mortality is less well characterised. Furthermore, although BMI is the most commonly used metric for categorising obesity, it is an insensitive measure of adiposity as it does not account for differences in body composition. Given that adipose tissue may serve as a reservoir for Covid-19 virus and thus a more severe course of illness [7], using alternative anthropometric indices that are more sensitive to adipose volume and its distribution to identify patients at risk of Covid-19-related death would be clinically helpful. However, as such data are not routinely collected before or during hospitalisation the association between Covid-19 outcomes and body composition remains unknown. Likewise, although metabolic syndrome has been identified as a risk factor influencing progression of the infection [8], the added risk of mortality conferred by its constituent parts, i.e. diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia, has not been reported.

Uniquely, the UK Biobank is a longitudinal cohort study containing clinical and anthropometric data collected before the pandemic [9, 10] that is also linked to national Covid-19 laboratory test data through Public Health England [11]. This has the added advantage that any association between Covid-19 outcomes and anthropometric indices and morbidity, respectively, are unlikely to be the result of reverse causation. We therefore leveraged this data repository to investigate whether there was an association between Covid19-related mortality and anthropometric and cardiometabolic data that was recorded prior to the pandemic amongst the UK Biobank cohort.

Methods

The UK Biobank [9] (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/) comprises 502,505 participants who were recruited between 2006 and 2010 at one of twenty-two assessment centres and were aged 40–69 years at the time. The current mean age of the cohort is 68 ± 8 years (range 49–86 years, 44% male). All participants provided informed consent at the time of recruitment for their data to be used for research purposes. Sociodemographic, lifestyle, health and anthropometric data were collected at baseline and during recall, for which protocols are publicly available [12]. Definitions of comorbidity were based on the main and secondary International Classification of Disease (ICD)-10 summary diagnoses or operative procedures.The latest Covid-19 data release (03/08/2020) included results from 16/03/2020 to 26/07/2020 and was accessed under application number 48666.

Age- and sex- adjusted logistic regression analyses were used to identify whether anthropometric indices [BMI (kg/m2), waist:hip ratio (WHR) and body fat (%)] and c-reactive protein (CRP) were associated with Covid-19-related mortality. Chi-squared test was conducted to identify the association between concurrent morbidity and Covid-19-related mortality. T test or Fisher’s exact test were used to compare characteristics of males vs females testing positive for Covid-19, and of normal weight vs obese individuals. Statistical analyses were performed using Python version 3.6 (Python Software Foundation) and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

By 28 August 2020, 13,502 UK Biobank participants (mean age 70 ± 8 years, range 50–84 years, 48.9% male) had been tested for Covid-19 using nasopharyngeal swabs. Of these, 1582 tested positive (mean age 68 ± 9 years, 52.8% male) and 11,920 negative. Among those that tested positive, 305 died (mean age 75 ± 6 years, 65.5% male).

Males testing positive for Covid-19 had a higher mortality than females (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.49–2.51, p < 0.0001), and tended to be older (69 ± 9 vs. 66 ± 9 years, p < 0.0001). Males that tested positive were also more likely to have hypertension, dyslipidaemia, arrhythmia, diabetes or angina than females. There was no difference in BMI between sexes. Comparisons between males and females testing positive are detailed in Table 1.

Referenced to normal BMI range (18.5 to < 25 kg/m2), participants with BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 (obese II) had significantly greater odds for Covid-19-related mortality (OR 1.70, 95% CI 1.06–2.74, p < 0.05). The odds for Covid-19-related mortality amongst individuals with BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 (underweight), 25 to < 30 kg/m2, (overweight) or 30 to < 35 kg/m2 (obese I) did not reach statistical significance.

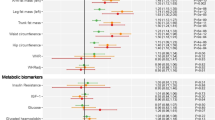

For every unit increase in BMI, WHR and percent body fat, the odds of death amongst the swab-positive participants increased by 1.04 (95% CI 1.01–1.07), 10.71 (95% CI 1.57–73.06) and 1.03 (95% CI 1.01–1.05), respectively (all p < 0.05, Table 2).

Swab-positive participants with pre-existing metabolic (diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia) or cardiovascular morbidity (atrial fibrillation, angina) also had higher odds of death (Table 2). The association between CRP and mortality did not quite reach statistical significance (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.00–1.04, p > 0.05).

Amongst those testing positive for Covid-19, individuals in the obese II category (BMI > 35 kg/m2) had greater odds ratios for hypertension, dyslipidaemia, atrial fibrillation, diabetes and angina than their normal weight (18.5 to 25 kg/m2) counterparts. There were no significant differences in age, or history of ventricular arrhythmia or stroke between these categories (Table 3).

Discussion

We show that increasing adiposity and pre-existing cardiometabolic morbidity are associated with higher Covid-19 related mortality amongst the UK Biobank population. Furthermore, participants with BMI > 35 kg/m2 had significantly higher odds of Covid-19 related mortality compared to those of a normal weight (BMI 18.5–25 kg/m2). As the participants of the UK Biobank represent a large sample of the British population that have undergone extensive phenotypic characterisation since 2006, these results can likely be extrapolated to the general population and are unlikely to be influenced by reverse causality. They also extend our current understanding of how these risk factors influence the course and severity of Covid-19 infection [4, 6, 13].

We demonstrate that central obesity, quantified by waist:hip ratio, is associated with Covid19-related mortality. We postulate that volume and distribution of adipose tissue may be a determinant of adverse outcomes observed in those with a high BMI. Covid-19 virus binds to the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor for intracellular invasion [14, 15]. Given that ACE2 is highly expressed in adipose as well as pulmonary tissue, it is unsurprising that obesity has been linked to a more severe illness [16]. It is, therefore, plausible that adipose tissue exerts a deleterious effect in Covid-19 infection by acting as a functional reservoir of the virus [17]. Inflammation of visceral adipose depots, such as epicardial fat that is contiguous with the myocardium, may also contribute to adverse outcomes by stimulating an augmented local and/or systemic inflammatory reaction in individuals with higher volumes of adiposity [13, 18, 19]. We anticipate it may be possible to ascertain whether subcutaneous or visceral adipose volumes and their respective distributions are associated with adverse Covid-19 outcomes as this data becomes available in a sufficient number of UK Biobank participants.

Counterintuitively, being overweight or obese is associated with a lower risk of viral infection and pneumonia, and underweight with a higher risk, compared to normal weight individuals [20]. On the other hand, individuals with a normal weight by BMI, but who nonetheless have central obesity according to WHR, have a higher risk of bacterial, not viral, infections [20]. Reasons for the so-called “obesity paradox” are not well understood. However, this phenomenon does not appear to be borne out in Covid-19 infection; indeed, our results would support the contrary. Excess adiposity weakens the innate immune system and may impair the clearance of viral infections [21], resulting in a persistent and perhaps exaggerated immune response in the context of a novel zoonotic viral infection compared to other seasonal viruses.

Obesity is associated with reduced respiratory reserve volume, functional capacity, and pulmonary tissue compliance. Central obesity also compromises pulmonary function, particularly in the supine position due to diaphragmatic splinting. These mechanical features make obese individuals and those with excess central adiposity more vulnerable to respiratory infections. The association between obesity and severe Covid-19 infection has previously been shown to remain significant after adjusting for glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and lipid profile, suggesting that increased adiposity is a risk factor [6]. Given that the association between increasing adiposity and Covid-19 related hospitalisation was only partially attenuated, and not negated, by HbA1c and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol [6] also supports the possibility that the adverse outcomes observed with concurrent obesity may be partly mediated by adiposity. This is consistent with other reports from other infections [22] and those that have linked unhealthy lifestyle choices and behaviours to a higher risk of Covid-19 [23]. We extend these findings by demonstrating that pre-existing metabolic perturbation (diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia) and cardiovascular disease (atrial fibrillation and angina) confer higher risk of Covid-19-related mortality in the same cohort. Obese individuals also had greater morbidity burden than their normal weight counterparts in our study. Given that cardiometabolic illnesses and obesity are chronic low-grade inflammatory phenotypes, cytokine activation may be amplified in the context of Covid-19 infection and may explain the higher mortality [7, 24, 25]. Similar to excess adipose tissue, a higher expression of ACE-2 receptor and consequently a greater viral load [26, 27], impaired neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis, increased furin and impaired T cell function are other mechanisms by which pre-existing metabolic perturbation may confer susceptibility to infection and adverse outcomes [28].

Despite the demonstrable utility of the UK Biobank for prognostication in Covid-19 infection, our analysis utilises data from middle-aged and older individuals. Therefore, the impact of adiposity and comorbidity on Covid-19 related outcomes in younger adults was not evaluated in our study. Although compelling, our analyses suggest an association, though not a direct causal link, between increasing adiposity and pre-existing morbidity and Covid-19-related mortality. A mendelian randomisation study may yield greater insight into the possible independent causal effects of adiposity in Covid-19 susceptibility and severity, given that obese participants had a greater comorbidity than their normal weight counterparts. We also cannot rule out changes in weight and adiposity from baseline during the course of follow-up of the UK Biobank.

Conclusion

In summary, we show that increasing adiposity and cardiometabolic morbidity are associated with higher Covid-19-related mortality amongst the UK Biobank cohort that tested positive for the infection. Adipose volume may influence the severity of Covid-19-related outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analysed during the current study are available in the UK Biobank repository, https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/. This can be accessed by formal application via the same link.

Abbreviations

- ACE2:

-

Angiotensin converting enzyme 2

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- Covid-19:

-

Coronavirus

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- HbA1c:

-

Glycated haemoglobin

- HDL:

-

High density lipoprotein

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- WHR:

-

Waist:hip ratio

References

WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 28]. https://covid19.who.int.

Website [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 1]. https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/.

Simonnet A, Chetboun M, Poissy J, Raverdy V, Noulette J, Duhamel A, et al. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity. 2020;28(7):1195–9.

Caussy C, Wallet F, Laville M, Disse E. Obesity is associated with severe forms of COVID-19. Obesity. 2020;28(7):1175.

Costa Monteiro AC, Suri R, Emeruwa IO, Stretch RJ, Cortes Lopez RY, Sherman A, et al. Obesity and smoking as risk factors for invasive mechanical ventilation in COVID-19: a retrospective, observational cohort study. medRxiv [Internet]. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.12.20173849.

Hamer M, Gale CR, Kivimäki M, Batty GD. Overweight, obesity, and risk of hospitalization for COVID-19: a community-based cohort study of adults in the United Kingdom. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A [Internet]. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2011086117.

Ryan PM, Caplice NM. Is adipose tissue a reservoir for viral spread, immune activation, and cytokine amplification in coronavirus disease 2019? Obesity. 2020;28(7):1191–4.

Costa FF, Rosário WR, Ribeiro Farias AC, de Souza RG, Duarte Gondim RS, Barroso WA. Metabolic syndrome and COVID-19: an update on the associated comorbidities and proposed therapies. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(5):809–14.

Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12(3):e1001779.

Bugbank Homepage [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 11]. Available from: http://www.bugbank.uk/index.html.

Bugbank Homepage [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: http://www.bugbank.uk/index.html.

Website [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 28]. Available from: UK Biobank. Protocol for a large-scale prospective epidemiological resource. https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/UK-Bi.

Deng M, Qi Y, Deng L, Wang H, Xu Y, Li Z, et al. Obesity as a potential predictor of disease severity in young COVID-19 patients: a retrospective study. Obesity [Internet]. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22943.

Cao Y, Li L, Feng Z, Wan S, Huang P, Sun X, et al. Comparative genetic analysis of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2) receptor ACE2 in different populations. Cell Discov. 2020;24(6):11.

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271-80.e8.

Malavazos AE, Romanelli MMC, Bandera F, Iacobellis G. Targeting the adipose tissue in COVID-19 [Internet]. Obesity. 2020;28:1178–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22844.

Kim I-C, Han S. Epicardial adipose tissue: fuel for COVID-19-induced cardiac injury? Eur Heart J. 2020;41(24):2334–5.

Amirfakhryan H, Safari F. Outbreak of SARS-CoV2: pathogenesis of infection and cardiovascular involvement. Hell J Cardiol [Internet]. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjc.2020.05.007.

Iacobellis G, Secchi F, Capitanio G, Basilico S, Schiaffino S, Boveri S, et al. Epicardial fat inflammation in severe COVID-19. Obesity [Internet]. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23019.

Hamer M, O’Donovan G, Stamatakis E. Lifestyle risk factors, obesity and infectious disease mortality in the general population: linkage study of 97,844 adults from England and Scotland. Prev Med. 2019;123:65–70.

Caci G, Albini A, Malerba M, Noonan DM, Pochetti P, Polosa R. COVID-19 and obesity: dangerous liaisons. J Clin Med Res [Internet]. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9082511.

Yang JK, Feng Y, Yuan MY, Yuan SY, Fu HJ, Wu BY, et al. Plasma glucose levels and diabetes are independent predictors for mortality and morbidity in patients with SARS. Diabet Med. 2006;23(6):623–8.

Hamer M, Kivimäki M, Gale CR, Batty GD. Lifestyle risk factors, inflammatory mechanisms, and COVID-19 hospitalization: a community-based cohort study of 387,109 adults in UK. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:184–7.

Maddaloni E, Buzzetti R. Covid-19 and diabetes mellitus: unveiling the interaction of two pandemics. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;e33213321.

Dietz W, Santos-Burgoa C. Obesity and its implications for COVID-19 mortality. Obesity. 2020;28(6):1005.

Patel VB, Mori J, McLean BA, Basu R, Das SK, Ramprasath T, et al. ACE2 deficiency worsens epicardial adipose tissue inflammation and cardiac dysfunction in response to diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2016;65(1):85–95.

Patel VB, Oudit GY. Response to comment on Patel et al. ACE2 deficiency worsens epicardial adipose tissue inflammation and cardiac dysfunction in response to diet-induced obesity. Diabetes 2016;65:85–95. Diabetes. 2016;65(2):e3–4.

Singh AK, Gupta R, Ghosh A, Misra A. Diabetes in COVID-19: prevalence, pathophysiology, prognosis and practical considerations. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):303–10.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

British Heart Foundation Grant (RG/16/3/32175) awarded to FSN, XL and NSP was used to access UK Biobank data by application. KHKP is a clinical research fellow and is supported by the National Institute for Health Research. The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KHKP wrote the manuscript, XL analysed the data, FSN conceived the research question, JKQ, JSW, NSP and FSN provided critical review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

UK Biobank data was accessed under application number 48666. All participants provided written informed consent for anonymised data to be used for research and publication at the time of enrolment [9]. This research conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

All participants provided written informed consent for their anonymised information to be used for health-related research purposes and the results thereof to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, K.H.K., Li, X., Quint, J.K. et al. Increasing adiposity and the presence of cardiometabolic morbidity is associated with increased Covid-19-related mortality: results from the UK Biobank. BMC Endocr Disord 21, 144 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-021-00805-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-021-00805-7