Abstract

Background

Diabetes is one of the most common metabolic disorders, with a high prevalence of patients with poor metabolic control. Worldwide, evidence highlights the importance of developing and implementing educational interventions that can reduce this burden. The main objective of this study was to analyse the impact of a lifestyle centred intervention on glycaemic control of poorly controlled type 2 diabetic patients, followed in a Community Care Centre.

Methods

A type 2 experimental design was conducted over 6 months, including 122 adults with HbA1c ≥ 7.5%, randomly allocated into Experimental group (EG) or Control Group (CG). EG patients attended a specific Educational Program while CG patients frequented usual care. Personal and health characterization variables, clinical metrics and self-care activities were measured before and after the implementation of the intervention. Analysis was done by comparing gains between groups (CG vs EG) through differential calculations (post minus pre-test results) and Longitudinal analysis.

Results

Statistical differences were obtained between groups for HbA1c and BMI: EG had a decrease in 11% more (effect-size r2 = .11) than CG for HbA1c (p < .001) and 4% more (effect-size r2 = .04) in BMI (p < .05). When controlling for socioeconomic characteristics and comorbidities that showed to be associated to each parameter in pre-test, from pre to post-test only EG participants significantly decreased HbA1c [Wilks’ ʎ = .702; F(1,57) = 24.16; p < .001; ηp2 = .298; observed power = .998]; BMI values [Wilks’ ʎ = .900; F(1,59) = 6.57; p = .013; ηp2 = .100; observed power = .713]; systolic Blood pressure [Wilks’ ʎ = .735; F(1,61) = 21.94; p < .001; ηp2 = .265; observed power = .996] and diastolic Blood pressure [Wilks’ ʎ = .795; F(1,59) = 15.20; p < .001; ηp2 = .205; observed power = .970].

Conclusions

The impact of a structured multicomponent educational intervention program by itself, beyond standard educational approach alone, supported in a Longitudinal analysis that controlled variables statistically associated with clinical metrics in pre-test measures, has demonstrated its effectiveness in improving HbA1c, BMI and Blood pressure values.

Trial registration

RBR-8ns8pb. (Retrospectively registered: October 30,2017).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diabetes, one of the most common metabolic disorders, is a public health concern rising with a widespread significance all over the world, with a clear tendency to increase in the next decades [1,2,3,4].

In Portugal, the country where this study was conducted, the estimated prevalence of diabetes is 13.1%, mainly in the age group between 20 and 79 years, mostly in type 2 sort. According to the National Diabetes Observatory, from the diabetic people with records of glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in Nacional Health Service (NHS), 21.8% have values over 8% [5]. This demonstrates that, despite the considerable research and health organizations and educators’ investment in this area, poor metabolic control is a major problem that seems to remain in a significant percentage of Portuguese patients.

Poor metabolic control has proven to be linked to the development of multiple complications, both acute and chronic, whose probability of appearance and aggravation can be reduced by improving glycaemic control and disease management [6].

Contributing to the prevention of earlier mortality and the decrease of patients’ quality of life [7] management of patients with complex diseases as type 2 diabetes, is a cornerstone of delaying and preventing complications and an important step towards improving clinical and metabolic outcomes, appropriate utilization of health care resources and the resulting health gains.

The Portuguese NHS responded to this imperative need by defining and implementing the concept of Therapeutic Education, an educational process, prepared, developed and carried out by trained health professionals, in order to enable the patient and their family to deal with a chronic illness situation, such as diabetes and with the prevention of its complications, aiming to maintain patients’ quality of life in a synergetic combination with additional therapeutics effect [8].

In addition, evidence has highlighted the importance of developing and implementing interventions that can reduce this burden, by using intensive strategies to control blood glucose levels [9, 10], pointing lifestyle correction as one of the most important aims for people with type 2 diabetes [4, 11, 12].

Described as a key-step for metabolic control in all the algorithms for diabetes treatment, educating for an adequate lifestyle is, currently, a recommendation present in all guidelines, due to the growing evidence of its effectiveness [13,14,15].

However, although this has been widely explored, as international literature reveals, little evidence has been produced about educational intervention effectiveness concerning the Portuguese reality. The interest and importance of evaluating the impact of educational intervention among poorly controlled type 2 diabetic patients lead to this research, structured according to the guidance on the development, evaluation and implementation of complex intervention to improve health, upon Medical Research Council framework [16, 17], aiming to analyse the impact of a lifestyle centred intervention on glycaemic control of poorly controlled type 2 diabetic patients, followed in a community care centre.

Guided and structured on the principles of Therapeutic Education, described on Table 1, an Educational Program was designed throughout a prior study, supported on theoretical and evidence based previous knowledge, along with an insightful analysis of the environment care reality [17].

This type of intervention has to be focussed on diabetes self-management education, a process in which knowledge and skills are provided for patients to perform self-care on a daily basis, as optimizing glycaemic control though self-management is the keystone of care in diabetic patients [18]. Thus, having present that the various components of an educational intervention necessary to embrace the several dimensions of self-management peculiarities [19], we designed a complex intervention that includes individual interaction between diabetes educators and patients; group approach, a main theme throughout the activity which was theoretically structured and planned as a trigger to motivate pair discussion, and telephone intervention, organized in a sequential global program [20, 21], schematically described on Fig. 1.

After a piloting procedure [16, 17], the Program was implemented in a Community Care Centre, offered to a group of poorly controlled type 2 diabetic patients [Experimental Group (EG)], while another group continued to receive the usual intervention, used in this health care institution, corresponding to the moments identified in the figure above as T1, T4 and T6 [Control Group (CG)]. By analysing the outcomes of this procedure, new contributions regarding the effects of a structured educational intervention program on metabolic control among Portuguese poorly controlled people with type 2 diabetes are highlighted. More specifically, we intend to ascertain whether a multicomponent educational program focused on lifestyle management strategies: (a) is significantly associated with metabolic control; (b) is effective on improving metabolic control; and (c) whether metabolic control is maintained after controlling for socioeconomic and health individual variables (comorbidities).

Methods

Participants

The sample is composed of two groups of adult/middle age patients with type 2 poorly controlled diabetes (HbA1c ≥ 7.5%/58.5 mmol/mol), followed in a Community Health Centre of the Portuguese NHS, using age and HbA1c as relevant control selection variables.

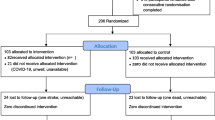

All the patients who fulfilled the relevant control criteria (n = 151) were invited during a routine consultation to participate in our study. From those, 136 agreed to do so, and were randomly allocated by the researcher into EG or CG in series of 2 patients for each group (2 for EG/ 2 for CG, and so on). The researcher was the only one in possession of the process number of the patient, without no further information (see flow diagram on Fig. 2).

The sample calculation was performed using the sample size determination formula based on the estimated proportion of the population with known p (proportion of the population of individuals belonging to the category we are interested in studying; p = 13.1% in 2014) and q (proportion of the population of individuals not belonging to the category we are interested in studying, 1 – p = 86.9%) [22]. So with a confidence level of 90% and α = 0.05, we would need at least 123 (rounded up from the figure of 123.22) subjects (our sample was composed of 136 participants).

Of the 136 participants, 122 concluded all the phases of the procedure (mortality rate of 10.3%): 64 in EG, between 35 and 67 year-old [M = 58.95 years, SD = 7.22 years] with HbA1c between 7.5% (58.5 mmol/mol) and 14% (129.5 mmol/mol) [M = 9.07%; SD = 1.47%] and 58 in CG, between 35 and 67 year-old [M = 55.97 years; SD = 8.28 years]; with HbA1c between 7.5% (58.5 mmol/mol) and 12.4% (112 mmol/mol) [M = 8.5%; SD = 1.04%].

Over 6 months, EG participants attended the Educational Program described on Fig. 1, while patients from CG frequented the usual care developed in the Community Care Unit (only 3 face-to-face moments, corresponding to moments T1, T4, and T6 identified in the same figure).

Materials

We collected clinical metrics [HbA1c, body mass index (BMI) and blood pressure (BP)], apart from personal and health characterization variables. Self-care activities were assessed using the Summary of Diabetes Self-care Activities Scale [23, 24] that was translated and validated for Portuguese patients [25], a measure that has proven to be sensible to self-care behavioural change [24].

Variables

As independent variable we considered the Group (CG versus EG), as EG followed the educational program procedures and CG followed the usual intervention developed in Community Centre. Dependent variables were HbA1c, BMI and BP measures. As control variables, supported on evidence based knowledge previously produced, we used socioeconomic characterization and personal health variables, namely, academic qualifications, cohabitation, economic difficulties, labour occupation, comorbidities (hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases, depression and anxiety, over weight and obesity, diabetes late complications and other comorbidities), adherence to diabetes self-care activities (SDSCA score) and to its dimensions (General diet, Specific diet, Exercise, Blood-glucose testing, Medications and Foot care).

Ethics and procedures

After Ethics Committee for Health from Regional Health Administration of Lisbon and Tagus Valley approval, the trial was registered with the ID 039/CES/INV/2014, following the Portuguese legislation. All the consort guidelines for reporting a clinical trial were followed, including informed consent, obtained from all patients.

Data were collected in two moments. The first time before the beginning of the educational program (pre-test) and the second after educational intervention program was finished (post-test). Anthropometric and clinical data were collected from clinical records and SDSCA was self-administered (an average of approximately 20 min of filling time). For all analyses we considered a probability of type I error (α) = 0.05.

Data analysis

This study has a type 2 experimental design [26], involving the measures of dependent variables before and after the implementation of an intervention and the manipulation of an independent variable (educational program designed vs. usual intervention).

Data were processed in IBM SPSS 22.0. For each dependent variable, the skewness and kurtosis didn’t show values indicating violations of the Normal Distribution (|Sk| < 3 and |Ku| < 8) [27, 28]. The Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances showed variance homogeneity across groups (p > .05).

Results

Clinical metrics within EG and CG in pre and post test

The comparison between pre and post-test CG and EG showed a significant decrease in all clinical metrics’ measures only in EG (see Table 2). For CG the only significant decrease was for diastolic blood pressure (BPd).

After these first results, we took the differential calculations (post minus pre-test results) of HbA1c, BMI, BPs and BPd measures as dependent variables, in order to compare the intervention gains between groups (CG vs EG), controlling for clinical metric results in pre-test. An independent-samples t-test was performed, taking as independent variable the group (CG versus EG) and as dependent variables the differential results (see Table 3). Statistical differences were obtained between groups for HbA1c and BMI: EG had an estimated decrease in 11% (effect-size r 2 = .111) more than CG for HbA1c and above 4% in BMI (effect-size r 2 = .038).

Despite these results, as our study groups (EG and CG) had significant differences on HbA1c levels at baseline, and literature points out several variables that can interfere in this process, we decided to conduct a Longitudinal analysis, an approach which permitted the examination of the effect of the Educational Program on clinical metrics from pre-test to post-test, while controlling for variables associated with these metrics. The differential calculations of dependent variables were used in order to control the differences found in the pre-test.

Socioeconomic characteristics and comorbidities associated with clinical metrics

As literature identifies, some variables are associated with clinical metrics in people with diabetes. In Table 4, correlations between these variables, diabetes control for significant associations are presented for control and experimental groups in pre-test. The variables which presented a significant association with clinical metrics were taken as control variables in the longitudinal analysis.

Clinical metrics from pre to post-test in CG and EG: Longitudinal analysis controlling for socioeconomic characteristics and comorbidities

Considering a longitudinal analysis, we began by examining the effects of educational program on clinical metrics from pre-test to post-test, while controlling for socio economic characteristics and comorbidities of participants which showed to be associated with these parameters in pre-test. We considered group (CG with usual intervention vs. EG with educational program) as a between-subjects factor, clinical metrics as within-subjects variables (from pre to post-test), and socioeconomic characteristics and comorbidities as covariates.

We performed four mixed ANCOVAs, one for each dependent variable (HbA1c, BMI, BPs, and BPd). According to intercorrelations found, for HbA1c we controlled for economic difficulties, overweight, self-care adherence score, general and specific diet and medication. For BMI we controlled for academic qualifications, depression, and for associated diagnosed diseases (overweight and obesity). For BPs we controlled for occupational labour and general diet and for BPd for academic qualifications, obesity, self-care adherence score and general diet.

For haemoglobin (HbA1c), despite the statistical removal of the effect of the covariates, we found a significant interaction between within-subjects variables and the between-subjects factor, Wilks’ ʎ = .893; F(1114) = 13.63; p < .001; η p 2 = .107; observed power = .955 (see Fig. 3). Through usual intervention done in the Community care Unit, CG didn’t decrease their HbA1c values from pre to post-test, Wilks’ ʎ = .993; F(1,51) = 0.36; p = .550; ηp 2 = .007; observed power = .091. Inversely, we noted that EG dropped significantly their HbA1c from pre to post-test, Wilks’ ʎ = .702; F(1,57) = 24.16; p < .001; η p 2 = .298; observed power = .998. We concluded that after controlling for these covariates, only experimental group participants significantly decreased HbA1c, with and effect size of 30%.

Evolution of HbA1c from pre to post-test as a function of educational program. Evolution of HbA1c from pre to post-test as a function of educational program (CG vs. EG) when controlling for socioeconomic characteristics and comorbidities. Covariates appearing in the model are evaluated at the following values: Economic difficulties (dummy) = .34; Overweight (dummy) = .20; Self-care adherence score = 3.8438; General diet = 3.28; Specific diet = 4.16; Medication = 6.34

When BMI was taken as dependent variable, and we controlled covariates associated with it, we also found a significant interaction between within-subjects variables and the between-subjects factor, Wilks’ ʎ = .967; F(1116) = 4.01; p = .048; η p 2 = .033; observed power = .510 (see Fig. 4). Control group didn’t decrease their BMI values from pre to post-test, Wilks’ ʎ = .999; F(1,53) = 0.08; p = .782; η p 2 = .001; observed power = .059. In reverse, experimental group dropped significantly their BMI from pre to post-test, although with a less effect size, Wilks’ ʎ = .900; F(1,59) = 6.57; p = .013; η p 2 = .100; observed power = .713.

Evolution of BMI from pre to post-test as a function of educational program. Evolution of BMI from pre to post-test as a function of educational program (CG vs. EG) when controlling for personal characteristics and comorbidities. Covariates appearing in the model are evaluated at the following values: Labour occupation (dummy) = .73; General diet = 3.28

As for BP as dependent variables, when we control covariates associated with diastolic and systolic blood pressure, the interactions between within-subjects variables and the between-subjects factors were significant, due to a decreased in both groups from pre to post-test, [BPs within-subjects variables: Wilks’ ʎ = .908; F(1118) = 12.03; p = .001; η p 2 = .092; observed power = .930; BPd within-subjects variables: Wilks’ ʎ = .920; F(1116) = 10.05; p = .002; η p 2 = .080; observed power = .882].

Once more, this decrease was only statistically significant for EG with effect sizes over 21% [BPs within-subjects variables: Wilks’ ʎ = .735; F(1,61) = 21.94; p < .001; η p 2 = .265; observed power = .996; BPd within-subjects variables: Wilks’ ʎ = .795; F(1,59) = 15.20; p < .001; η p 2 = .205; observed power = .970] as for CG we obtained: BPs within-subjects variables: Wilks’ ʎ = .954; F(1,55) = 2.67; p = .108; η p 2 = .046; observed power = .362 and BPd within-subjects variables: Wilks’ ʎ = .918; F(1,53) = 4.72; p = .34; η p 2 = .082; observed power = 569 (see Fig. 5).

Evolution of BPs and BPd from pre to post-test as a function of educational program. Evolution of BPs and BPd from pre to post-test as a function of educational program (CG vs. EG) when controlling for socioeconomic characteristics and comorbidities. Covariates appearing in the model are evaluated at the following values: BPs: Overweight (dummy) = .20; academic qualifications (dummy) = .54; depression (dummy) = .16; obesity (dummy) = .37; BPd: academic qualifications (dummy) = .54; obesity (dummy) = .37; self-care adherence score = 3.8438; general diet = 3.28

Discussion

This study, an experimental controlled research, was conducted with the purpose of determining whether an educational specific program was effective in improving metabolic control of a group of poor controlled type 2 diabetic patients, as evidence has shown that metabolic control can be accomplished by multicomponent interventions based on Therapeutic Education, addressing healthy lifestyle and self-management [18, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

Although published evidence-based exists, this is a research area little explored in Portuguese reality with few available studies centred on educational intervention effectiveness assessment. Portugal is one of the European countries where often health expected outcomes fail to meet guidelines due to multiple known barriers to health professionals’ intervention and patients’ outcomes achievement [18, 36,37,38].

The findings of our study clearly support previous studies on improvement of HbA1c levels through diabetes education [33, 39,40,41]. Throughout a first analysis it can be noted that, between pre and post-test, clinical metrics were sensible to the educational intervention. Emphasis is, however, that only in EG were identified statistically significant differences in these variations.

The most important metabolic control indicator for type 2 diabetic patients, glycosylated haemoglobin, is only significantly reduced in EG participants, with an estimated decrease of 11% more than in CG (differential calculations, controlling for Glycosylated haemoglobin in pre-test). The same applies to BMI variation, another cornerstone for diabetes health related outcomes, although this variation has a minor estimated decrease and its clinical value may be of lower significance. Blood pressure was the other clinical metric analysed in this study, due to the well-known relation between hypertension and diabetes, a condition that often affects people with type 2 diabetes. Results show both systolic and diastolic values have decreased from pre to post test, although without statistical significance.

Impact of the educational program by itself is supported in the Longitudinal analysis, when variables statistically associated with clinical metrics in pre-test measures were controlled. Notwithstanding the statistical removal of the effect of the covariates, a significant interaction between within-subjects variables and the between-subjects factor remains, leading to the conclusion that only in experimental group participants a significantly decreased in clinical metrics can be verified, as identified in other studies [42].

With distinct effect sizes, we confirmed experimental group participants reduced significantly clinical parameters from pre to post-test. EG participants registered a statistical significant decrease of HbA1c values with an effect size of 11%; of BMI, although effect size is lower (3%) and of BP (systolic −27%, diastolic – 21%). CG participants didn’t have a significant decrease in HbA1c values (p = .550), in BPs (p = .108) or in BPd (p = .34) and BMI increased from pre to post-test, although it didn’t have statistical significance (p = .782). These outcomes also are in line with the ones from other studies [33, 39,40,41].

Furthermore, our results sustain the impact of a structured multicomponent educational intervention on improving clinical metrics, beyond standard educational approach alone [40, 43,44,45], as all the participants received educational intervention, regardless of the group they were allocated to and results evidence differences between groups which are statically significant.

Conclusions

It is known that often health expected outcomes fail to meet guidelines, patients’ expectations and needs, due to multiple known barriers to health professionals’ intervention and patients’ outcomes achievement[ [18, 36,37,38].

Education and lifestyle modification are identified as critical components for metabolic and clinical control in diabetic patients. Evidence-based reports have emphasized the importance of education for type 2 diabetic patients and educational programmes have confirmed their role in glycaemic control and decreasing diabetes associated complications [46].

The accuracy and innovative contribution of the present study is intended to be the assessment of the effectiveness of a specific educational program, designed upon an exploratory trial, where detailed educational needs of a group of Portuguese people with type 2 diabetes, were identified and taken into account in the definition of the Complex Intervention.

The multicomponent educational program, structured on the principle of Therapeutic Education, has proven its effectiveness, especially with regard to metabolic control, by lowering HbA1c with statistical evidence between groups (CG vs EG), result reinforced when correlated variables were controlled.

Nevertheless, these results should be interpreted with some consideration due to the limitations of the study, mainly related to the baseline difference in HbA1c levels between groups (EG and CG). There was even an aleatory patient distribution into groups, which leads us to suggest more research with Portuguese patients, analysing the impact of these programs in health gains, especially if randomization can be achieved.

Abbreviations

- ADA:

-

American Diabetes Association

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- BPd:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- BPs:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- CDA:

-

Canadian Diabetes Association

- CES:

-

Comissão de Ética para a Saúde (Health Ethics Committee)

- CG:

-

Control Group

- EG:

-

Experimental Group

- et al.:

-

et alia (and others)

- HbA1c:

-

Glycosylated haemoglobin

- IBM SPSS:

-

International Business Machines- Software Package for Social Sciences

- IDF:

-

International Diabetes Federation

- INV:

-

Investigação (Research)

- M:

-

Mean

- MRC:

-

Medical Research Council

- NHS:

-

Nacional Health Service

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SDSCA :

-

Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities

References

WHO. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. 2011. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44579/1/9789240686458_eng.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2015.

WHO. Fact sheet N°312. Updated January 2015. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/. Accessed 26 Feb 2016.

CDA. Clinical Practice Guidelines. Can J Diab, 2013; 37: 1.

ADA. Standards of medical care in diabetes - 2015; The Journal of Clinical and Applied Research and Education 2015; 38:1.

Diabetes Observatory. Diabetes. Facts and Numbers. Portugal 2014. Annual Report on the National Diabetes Observatory 2015. https://www.dgs.pt/paginaRegisto.aspx?back=1&id=27006. Accessed 30 Mar 2016.

Brunisholz K, Briot P, Hamilton S, Joy E, Lomax M, Barton N,. .. Cannon W. Diabetes self-management education improves quality of care and clinical outcomes determined by a diabetes bundle measure. J Multidiscip Healthc 2014; 7: 533–542.

Schunk M, Reitmeir P, Schipf F, Völzke H, Meisinger C, Thorand B, Holle R. Health-related quality of life in subjects with and without type 2 diabetes: pooled analysis of five population-based surveys in Germany. Diabet Med. 2012; doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03465.x.

DGS [NHS Portuguese Management Department]. Therapeutic Education in Diabetes. Normative Information n° 14/DGDG from 12/12/2000. 2000. Health Ministry: Lisbon.

Holman R, Paul S, Bethel M, Matthews D, Neil H. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1577–89.

Heianza Y, Suzuki A, Fujihara K, Tanaka S, Kodama S, Hanyu O, Sone H. Impact on short-term glycaemic control of initiating diabetes care versus leaving diabetes untreated among individuals with newly screening-detected with newly screening-detected. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014; doi:10.1136/jech-2014-204054.

Nathan D, Buse J, Davidson M, Ferrannini E, Holman R, Sherwin R, Zinman B. Medical management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy. A consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of diabetes. Diab Care. 2009;32:193–203.

Duarte R, Silva Nunes J, Dores J, Rodrigues E, Raposo J, Carvalho D, et al. Recomendações Nacionais da SPD para o tratamento da Hiperglicemia na Diabetes Tipo 2 - Versão resumida. Rev Port Diab. 2013;8(1):30–41.

Norris S, Engelgau M, Naraya V. Effectiveness of Self-Management Training in Type 2 Diabetes. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diab Care. 2001;24(3):561–87.

Horton E, Cefalu W, Haines S, Siminerio L. Multidisciplinary interventions: mapping new horizons in diabetes care. Diab Educ. 2008;34(Suppl 4):78S–89S.

Colagiuri R, Girgis S, Eigenmann C, Gomez M, Griffiths R. National Evidence-Based Guideline for patient education in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Australia and the NHMRC: Canberra, Australia; 2009.

MRC. A framework for development and evaluation of RCTs for complex interventions to improve health. Medical Research Council. 2000. http://www.mrc.ac.uk/ documents/pdf/rcts-for-complex-interventions-to-improve-health/. Accessed 12 Jan 2015.

MRC. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. 2008. http://www.mrc.ac.uk/ complexinterventionsguidance. Accessed 12 Jan 2015.

Shakibazadeh E, Larijani B, Shojaeezadeh D, Bartholomew L. Patients’ Perspectives on Factors that Influence Diabetes Self-care. Iranian J Publ Health. 2011;40(4):146–58.

IDF. Clinical Guidelines Task Force. Global guideline for type 2 Diabetes. International Diabetes Federation, 2012; https://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/IDF%20T2DM%20Guideline.pdf. Accessed 15 Mar 2015.

Pinto MR, Parreira P, Basto ML, Rei A & Monico L. Lifestyle Educational Programme for primary care diabetic patients: the design of a complex nursing intervention, BMC Health Services Research 2016a; 16 Suppl 3:O16.

Pinto, MR, Parreira, P, Basto, ML & Monico, L. Therapeutic Education: The design of an educational program protocol for primary care diabetes patients. Proceedings of 5th Euro Nursing &Medicare Summit, Rome, Italy, 2016b, p. 90.

Levine D, Berenson M, Stephan D. Estatística: Teoria e aplicações usando Microsoft Excel em Português (6ª ed.). 2014. Rio de Janeiro: LTC.

Toobert D, Glasgow R. Assessing diabetes self-management: the summary of diabetes self-care activities questionnaire. In: Gordon C, editor. Handbook of psychology and diabetes: a guide to psychological measurement in diabetes research and practice. Langhorne, PA, England: Harwood Academic Publishers/Gordon; 1994. p. 351–75.

Toobert D, Hampson S, Glasgow R. The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Measure. Results from 7studies and a revised scale. Diab Care. 2000;23(7):943–50.

Bastos F, Severo M, Lopes C. Propriedades psicométricas da escala de autocuidado com a diabetes traduzida e adaptada. Acta Medica Port. 2007;20:11–20.

Richards D, Coulthard V, Borglin G. The state of European nursing research: dead, alive or chronically diseased? A systematic literature review. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2014; doi:10.1111/wvn.12039.

Finney S, DiStefano C. Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In: Hancock G, Muller R, editors. Structural equation modeling: a second course (Quantitative Methods in Education and the Behavioral Sciences: Issues, Research, and Teaching). Charlotte: Information Age Publishing; 2006. p. 269–314.

Kline R. Principles and practice of strutuctural equation modeling. 3rd ed. New York: the Guilford Press; 2011.

Norris S, Lau J, Smith S, Schmid C, Engelgau M. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diab Care. 2002a;25(7):1159–71.

Norris S, Nichols P, Caspersen C, Glasgow R, Engelgau M, Jack Jr L, McCulloch D. Increasing diabetes self-management education in community settings a systematic review. Am J Prev Med, 2002b; 22 Suppl 4:39–66.

Warsi A, Wang P, LaValley M, Avorn J, Solomon D. Self-management education programs in chronic disease: a systematic review and methodological critique of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(15):1641–9.

Deakin T, McShane C, Cade J, Williams R. Group based training for self-management strategies in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD003417.

Clark M. Diabetes self-management education: a review of published studies. Primary Care Diabetes. 2008; doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2008.04.004.

Rasekaba T, Graco M, Risteski C, Jasper A, Berlowitz D, Hawthorne G, Hutchinson A. Impact of a diabetes disease management program on diabetes control and patient quality of life. Population Health Management. 2012; doi:10.1089/pop.2011.0002.

Li R, Shrestha S, Lipma R, Burrows N, Kolb L, Rutledge S. Diabetes self-management education and training among privately insured persons with newly diagnosed diabetes — United States, 2011–2012. MMWR. 2014;63:46.

Meetoo D, McGovern P, Safadi R. An epidemiological overview of diabetes across the world. Br J Nurs. 2007;16(16):1002–7.

Gardete-Correia L, Boavida J, Raposo J, Mesquita A, Fona C, Carvalho R & Massano-Cardoso S. First diabetes prevalence study in Portugal: PREVADIAB study. Diabet Med 2010; doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03017.x.

Yamashita T, Kart C & Noe D. Predictors of adherence with self-care guidelines among persons with type 2 diabetes: results from a logistic regression tree analysis. J Behav Med, 2012; doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9392-y.

Minet L, Møller S, Vach W, Wagner L & Henriksen J. Mediating the effect of self-care management intervention in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of 47 randomised controlled trials. Patient Education and Counselling. 2010; 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.033.

Steinsbekk A, Rygg L, Lisulo M, Rise M, Fretheim A. Group diabetes self-management education compared to routine treatment for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A systematic review with meta-analysis BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12:213.

Menino E, Dixe M, Louro M & Roque S. Programas de educação dirigidos ao utente com diabetes mellitus tipo 2: revisão sistemática da literatura. Rev Enf Referência. 2013; doi:10.12707/RIII1247.

Adachi M, Yamaoka K, Watanabe M, Nishikawa M, Kobayashi I, Hida E, Tango T. Effects of lifestyle education program for type 2 diabetes patients in clinics: a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:467.

Song M, Kim H. Effect of the diabetes outpatient intensive management programme on glycaemic control for type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Nurs. 2007; doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01800.x.

Hawthorne K, Robles Y, Cannings-John R, Edwards AG. Culturally apprpriate health education for type 2 diabetes mellitus in ethnic minority groups. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006424.pub2.

Pinto MR, Parreira P & Basto ML. Resultados da intervenção de enfermagem na adequação do estilo de vida das pessoas com Diabetes Mellitus tipo 2. Uma Revisão Sistemática da literatura. Revista da UIIPS, 2014; 5:2:259–78.

Likitmaskul S, Wekawanich J, Wongarn R, Chaichanwatanakul K, Kiattisakthavee P, Nimkarn S,. .. Tuchinda C. Intensive diabetes education program and multidisciplinary team approach in management of newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes mellitus: a greater patient benefit, experience at Siriraj hospital. J Med Assoc Thail, 2002; 85: 488–495.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Professor Salwa Porto for the written English review and the collaboration of all participants and staff from the Community Care Center where this study was developed.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MRP conceived the idea for the research, wrote the framework, and drafted the manuscript as the principal author. PP participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. MLB made substantial contributions to conception, framework and design. LM was responsible for the data analysis and revision of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was done by Ethics Committee for Health from Regional Health Administration of Lisbon and Tagus Valley with the registration identification: 039/CES/INV/2014. Written informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants, using a formulary approved by Ethics Committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

do Rosário Pinto, M., Parreira, P.M.D.S., Basto, M.L. et al. Impact of a structured multicomponent educational intervention program on metabolic control of patients with type 2 diabetes. BMC Endocr Disord 17, 77 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-017-0222-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-017-0222-2