Abstract

Background

We aimed to investigate if there was any relationship between screen time (ST) and the severity of primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis (PMNE) and treatment success.

Methods

This study was conducted in urology and child and adolescent phsychiatry clinic in Afyonkarahisar Health Sciences University Hospital. After diagnosis patients were seperated by the ST for exploring causation. Group 1 > 120, Group 2 < 120 (min/day). For the the treatment response, patients were grouped again. Group 3 patients were administered 120 mcg Desmopressin Melt (DeM) and were requested < 60 min ST. Patients in Group 4 were given 120 mcg DeM solely.

Results

The first stage of the study included 71 patients. The ages of the patients ranged from 6 to 13. Group 1 comprised 47 patients, 26 males and 21 females. Group 2 comprised 24 patients,11 males and 13 famales. Median age was 7 years in both groups. The groups were similar in respect of age and gender (p = 0.670, p = 0.449, respectively). A significant relationship was determined between ST and PMNE severity. Severe symptoms were seen at the rate of 42.6% in the Group 1, and at 16.7% in the Group 2 (p = 0.033). 44 patients completed the second stage of the study. Group 3 comprised 21 patients, 11 males and 10 females. Group 4 comprised 23 patients,11 males and 12 famales. Median age was 7 years in both groups. The groups were similar in respect of age and gender (p = 0.708, p = 0.765, respectively). Response to treatment was determined as full response in 70% (14/20) in Group 3 and in 31% (5/16) in Group 4 (p = 0.021). Failure was determined in 5% (1/21) in Group 3 and in 30% (7/23) in Group 4 (p = 0.048). Recurrence was determined at a lower rate in Group 3 where ST was restricted (7% vs. 60%, p = 0.037).

Conclusion

High screen exposure may be a factor for PMNE aetiology. And also reducing ST to a normal range can be an easy and beneficial method for treatment of PMNE.

Trial Registration ISRCTN15760867(www.isrctn.com). Date of registration: 23/05/2022. This trial was registered retrospectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis, commonly known as bedwetting, is defined as intermittent night-time bedwetting only, without any daytime lower urinary tract symptoms. When this continues without a 6-month dry period, it is known as primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis (PMNE). This is accepted physiological up to the age of 5 years and for cases older than 6 years, treatment is recommended [1, 2].

Three important pathophysiological factors are responsible for PMNE. Two of these factors are an increase in respect of night-time in the day-night urine output ratio, and reduced nocturnal functional bladder capacity. However, the main pathophysiology is believed to be an increased threshold of waking from sleep despite the fullness of the bladder. There has been seen to be a difference in REM sleep in bedwetting children compared to normal children, which has been proven in sleep disorder laboratory tests. Therefore, many reasons which could lead to sleep disorders, primarily adenotonsillar hypertrophy have been the subject of research for the etiology of PMNE [3,4,5,6]. In recent studies, screen time (ST) exposure has been reported to be a factor that could lead to sleep disorders. It has been determined that excessive screen time (EST) which could lead to emotional, cogntive and behavioural problems, also impairs sleep quality [7, 8].

With the consideration that screen time could be a pathophysiological factor of sleep disorder in children diagnosed with PMNE, the aim of this study was to investigate whether there was any relationship between screen time and the degree and severity of PMNE and treatment success.

Methods

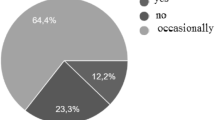

This study was conducted in urology and child and adolescent phsychiatry clinic in Afyonkarahisar Health Sciences University Hospital. After ethical approval (Afyonkarahisar Health Sciences University Clinical Research Ethics Committee. 2011-KAEK-2, 2021/198) we recorded the data prospectively (Clinical trial registration: ISRCTN15760867. 23/05/2022). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardian of the participation include the study.. The study included the families of patients who presented because of bedwetting and were diagnosed with PMNE from the history, a 2-day complete voiding-drinking diary and urine analysis. All the families participated voluntarily and no patient had previously received treatment. Patients were excluded if they had any neurological disease, obstructive respiratory tract disease, diabetes mellitus, or body mass index > 95th percentile and reduced bladder capacity detected by voiding diary (Koff Formula; Bladder capacity (ounces) = age (years) + 2) [9]. After the diagnosis of PMNE, the parents were requested to keep a diary for 1 week of the minutes of screen time (ST) (television, tablet, computer, mobile telephone, video game console). At the first stage of the study, feedback was obtained from 71 families. To determine the relationship between ST and the degree and severity of PMNE symptoms, the patients were separated into two groups as Group 1 with mean screen time (MST) > 120 min per day and Group 2 with < 120 min MST per day (Fig. 1).

The age and gender of each patient was recorded and PMNE was classified as described in previous studies as mild (1–2 wet nights/week), moderate (3–5 wet nights/week) and severe (6–7 wet nights/week).4 The mean number of wet nights per week were recorded and the groups were compared according to these parameters.

Patients who wanted an active treatment who were not willing to take the conservative “wait and see” approach were also included in the study to see the effect of ST restriction in the treatment of PMNE. Thus, at the second stage, 62 of 71 patients were included, but only 44 could complete the study. Patients were allocated to 2 groups using randomly generated numbers with a computer software program (www.Randomizer.org). Group 3 patients were administered 120 mcg Desmopressin Melt (DeM) and in addition to supportive treatment were requested to reduce daily screen time (DST) to < 60 min. Patients in Group 4 were given 120 mcg Desmopressin Melt (DeM) and supportive treatment was recommended (Fig. 1).

The response to treatment was measured at the end of 3 months. Full response was defined as 100% dryness, partial response as 50–99% dryness and failure as < 50% dryness. For the patients with full response in both groups, the DeM treatment was terminated and at a follow-up visit 1 month later they were questioned about recurrence. The groups were statistically compared in respect of descriptive data, response to treatment and recurrence.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS.21.0) software. The distribution of pretreatment descriptive data and the posttreatment values was determined with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. For independent variables with parametric distribution, the t-test (mean ± std) was applied and for variables with non-parametric distribution, the Mann Whitney U-test (median, min–max). Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used for qualitative data. A value of p < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

The first stage of the study included 71 patients ranging in age from 6 to 13 years. Group 1 comprised 47 patients with MST 142.27 ± 23.32 min and Group 2 comprised 24 patients with MST 90.25 ± 15.68 min. The groups were similar in respect of age and gender (p = 0.670, p = 0.449, respectively). In the comparison of symptom severity, in Group 1, 19.1% of patients were determined with mild, 38.3% with moderate and 42.6% with severe PMNE. In Group 2, 33.3% were determined with mild, 50.0% with moderate and 16.7% with severe PMNE. The difference between the groups was statistically significant (p = 0.033). The mean number of wet nights was 4.61 ± 1.73 in Group 1 and 3.79 ± 1.74 in Group 2, with no statistically significant difference between the groups (Table 1).

In the second stage of the research, Group 3 and Group 4 were found to be statistically similar in respect of age before treatment, gender, symptom severity, number of wet nights per week and daily screen time (DST) (p = 0.708, p = 0.765, p = 0.559, p = 0.569, p = 0.532, respectively) (Table 2). After 3 months of treatment and restricted screen time, median ST was calculated as 52 min (range, 30–60 min) in Group 3 and 120 min (range, 76–180 min) in Group 4 (p < 0.001).

Patients in Group 3 reported complying with the rule of DST < 60 min throughout the study. Response to treatment measured at 3 months was determined as full response in 70% (14/20) in Group 3 and in 31% (5/16) in Group 4 (p = 0.021). Failure in response to treatment was determined in 5% (1/21) in Group 3 and in 30% (7/23) in Group 4 (p = 0.048) (Table 2). Recurrence at 1 month after the completion of treatment was determined at a lower rate in Group 3 where DST was restricted (7% vs. 60%, p = 0.037) (Table 2).

Discussion

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics guideline, ST exposure for children aged 2–5 years should be limited to 1 h per day. This limitation is relaxed for children over 5 years of age taking daily physical activity (1 h) and sleep duration (8–12 h) into consideration and under family controlled conditions of content and not sleeping in the same room as media devices (telephone, tablet, television etc.) [10]. With developing technology and digital devices, the ST exposure of children has beome an increasing problem throughout the world [11, 12]. In addition to being a family problem, as ST can disrupt the parent–child relationship, ST has also been held responsible for many pathologies from neurodevelopmental problems of the child to sleep disorders [7, 8].

Several studies have shown that sleep disorders and an impaired waking threshold could be risk factors for PMNE [3, 13, 14]. In treatment, it is attempted to eliminate these changeable risk factors. Invasive methods such as rapid maxillary expansion and adenotonsillectomy for sleep disorders associated with respiratory tract obstruction have been reported to be successful in enuresis treatment [15, 16]. In a study by Kaya et al. [4], it was reported that even passive smoking exposure, which can be simply changed, reduces the success of DeM treatment in PMNE.

In the light of previous studies, we want to investigate the relationship between ST and bedwetting, which is known to have a psychological effect on school-age children. In the first stage of the study, a significant relationship was determined between ST and PMNE severity. Severe symptoms were seen at the rate of 42.6% in the group with more screen exposure, and at 16.7% in the group with less ST. It was then aimed to evaluate the effect of limiting ST on the success of DeM medical treatment in children who started active treatment at the request of their parents.

In important publications in literature, a full response to DeM treatment has been reported of approximately 30%, and in the current study, this rate was 31%, as expected, in patients receiving DeM and supportive treatment [17]. However, it is noteworthy that the response to treatment was 70% in the group which reduced ST from an initial median 135–52 min as a result of our recommendations in addition to the DeM and classic treatment. Similar success was obtained in the recurrence rates at 1 month after completing treatment in the group which restricted ST (7% vs. 60%). However, it is not clear whether these data determined in this study have an organic cause such as neurological sleep disorder known to be caused by excessive screen time (EST), or if this pathology is the result of the psychological motivation source of family participation in treatment, which is known to be important, as stated in previous studies [18].

There are some limitation factors in our study. For example, family history of enuresis and sociocultural status were ignored, which might affect the first part of the study. The small cohort, hight drop out rate are the other limitations.

Conclusıons

In conclusion, bringing ST to a normal range, which should be controlled in childhood, can be considered to contribute to the treatment of PMNE, just as it will contribute to a sufficient level of physical activity in children. This method which can be easily applied and is beneficial shows a positive effect on response to treatment and recurrence. Nevertheless, there is a need for further randomised, controlled studies and meta-analyses, as required by evidence-based medical regulations, to support these results.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ST:

-

Screen time

- PMNE:

-

Primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis

- EST:

-

Excessive screen time

- MST:

-

Mean screen time

- DeM:

-

Desmopressin Melt

- DST:

-

Daily screen time

- MNWN:

-

Mean number of wet nights per week

References

Radmayr C, Bogaert G, Dogan HS, Nijman JM, Rawashdeh YFH, Silay MS, et al. EAU pediatric urology guideline-2021. https://uroweb.org/guideline/paediatric-urology/.

Läckgren G, Hjälmås K, van Gool J, von Gontard A, de Gennaro M, Lottmann H, et al. Nocturnal enuresis: a suggestion for a European treatment strategy. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:679–90.

Collier E, Varon C, Van Huffel S, Bogaert G. Enuretic children have a higher variability in REM sleep when comparing their sleep parameters with nonenuretic control children using a wearable sleep tracker at home. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39:367–75.

Kaya Aksoy G, Semerci Koyun N, Doğan ÇS. Does smoking exposure affect response to treatment in children with primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis? J Pediatr Urol. 2020;16:47.e1-47.e6.

Haid B, Tekgul S. Primary and secondary enuresis: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Eur Urol Focus. 2017;3(2–3):198–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2017.08.010.

Zhu W, Che Y, Wang Y, Jia Z, Wan T, Wen J, Cheng J, Ren C, Wu J, Li Y, Wang Q. Stud on neuropathological mechanisms of primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis in children using cerebral resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):19141. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55541-9.

Hale L, Guan S. Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;21:50–8.

Lin J, Magiati I, Chiong SHR, Singhal S, Riard N, Ng IH, et al. The relationship among screen use, sleep, and emotional/behavioral difficulties in preschool children with neurodevelopmental disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2019;40:519–29.

Koff SA. Estimating bladder capacity in children. Urology. 1983;21(3):248.

Reid Chassiakos Y, Radesky J, Christakis D, Moreno MA, Cross C. Children and adolescents and digital media. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20162593.

Barber SE, Kelly B, Collings PJ, Nagy L, Bywater T, Wright J. Prevalence, trajectories, and determinants of television viewing time in an ethnically diverse sample of young children from the UK. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14:88–99.

Cheng S, Maeda T, Yoichi S, Yamagata Z, Tomiwa K, Japan Children’s Study Group. Early television exposure and children’s behavioral and social outcomes at age 30 months. J Epidemiol. 2010;20:482–9.

Wolfish NM, Pivik RT, Busby KA. Elevated sleep arousal thresholds in enuretic boys: clinical implications. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86:381–4.

Nevéus T, Stenberg A, Läckgren G, Tuvemo T, Hetta J. Sleep of children with enuresis: a polysomnographic study. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1193–7.

Timms DJ. Rapid maxillary expansion in the treatment of nocturnal enuresis. Angle Orthod. 1990;60:229–34.

Firoozi F, Batniji R, Aslan AR, Longhurst PA, Kogan BA. Resolution of diurnal incontinence and nocturnal enuresis after adenotonsillectomy in children. J Urol. 2006;175:1885–8.

Neveus T, Eggert P, Evans J, Macedo A, Rittig S, Tekgül S, Vande Walle J, Yeung CK, Robson L, International Children’s Continence Society. Evaluation of and treatment for monosymptomatic enuresis: a standardization document from the International Children’s Continence Society. J Urol. 2010;183:441–7.

Butler RJ, Brewin CR, Forsythe WI. Maternal attributions and tolerance for nocturnal enuresis. Behav Res Ther. 1986;24:307–12.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AD: Conception and design, Collected data, analysis and interpretation of data, final approval. HGG: Collected data, reviewed the paper, drafting of the manuscript and final approval. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Afyonkarahisar Health Sciences University Clinical Research Ethics Committee (2011-KAEK-2, 2021/198). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations of Helsinki declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants parents or legal guardian included in the study.

Consent for pubilcation

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Demirbas, A., Gercek, H.G. The effect of screen time on the presentation and treatment of primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. BMC Urol 23, 22 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-023-01184-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-023-01184-y