Abstract

Background

Renal schwannomas are very rare and are usually benign. Its clinical symptoms and imaging features are nonspecific, and the diagnosis is usually confirmed by pathology after surgical resection.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old Chinese female was admitted to the hospital with right flank pain that had persisted for the six months prior to admission. This pain had worsened for 10 days before admission, and dyspnea occurred when she was supine and agitated. A right abdominal mass could be palpated on physical examination. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging examinations revealed a large, nonenhanced, cystic and solid mass in the right kidney. The patient received radical nephrectomy for the right kidney. The diagnosis of schwannoma was confirmed by pathological examination.

Conclusions

We report a case of a large renal schwannoma with obvious hemorrhage and cystic degeneration, which can be used as a reference for further study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Schwannomas are predominantly benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors. These tumors rarely undergo malignant transformation. Schwannomas are most commonly seen in the extremities, head, neck, retroperitoneum and mediastinum. Rarer locations include the kidney, duodenum [1], bronchus [2], and other internal regions. Renal schwannomas more frequently arise from the hilum and less frequently arise from the parenchyma because nerve tissues congregate at the hilum [3]. We report a case of large schwannoma originating from the renal parenchyma.

Case presentation

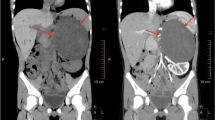

A 46-year-old Chinese female had right flank of unclear origin pain that lasted more than six months. It began with slight and persistent dull pain and no other symptoms. Ten days before admission, however, the pain worsened, and dyspnea occurred when she was supine and agitated. A right abdominal mass with poor mobility and a clear boundary between the surrounding structures could be palpated on physical examination. There was no tenderness. The patient had no genetic history of neurofibromatosis. No abnormal findings were found on blood, biochemistry, routine urine and antibody laboratory examination. Nonenhanced CT showed a large cystic and solid mass in the right kidney with septation and a few areas of calcification that increased the volume of the right kidney. The renal cortex had become thinner, and the renal pelvis and calices were obviously hydrous and dilated. The adjacent organs were compressed and displaced (Fig. 1). MRI revealed that the mass was slightly hyperintense on T1-weighted imaging, and had high-low mixed signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging. The edge of the lesion showed hyperintensity on diffusion-weighted imaging, and ring-like and septal enhancement was observed on enhanced T1-weighted imaging (Fig. 2). Because the mass was so large, the patient underwent radical nephrectomy of the right kidney, which revealed that the mass had adhered tightly to the inferior vena cava and duodenum. Postoperative pathology showed that the mass from the renal parenchyma measured 20.5 × 17.5 × 10.0 cm and was encapsulated. On cut sections, it was soft and reddish-brown with a massive amount of hemorrhage and necrosis. The boundary between the mass and renal parenchyma was clear. Immunostaining with S-100 protein and Ki-67 (positivity in approximately five percent of neoplastic cells) was positive and supported a diagnosis of a benign schwannoma (Fig. 3). Postoperatively, the patient recovered well, and no complications were observed.

MR findings of renal schwannoma. a Precontrast T1-weighted MR shows a slightly hyperintense mass (white arrow) arises from the kidney. T2-weighted axial (b) and cronal (c) plane MR shows the high-low mixed signal intensity mass (white arrow) with hydronephrosis (red arrow). No obvious enhancement (white arrow) on enhanced T1-weighted imaging (d)

Discussion and conclusions

Peripheral schwannoma is an uncommon tumor that originates from Schwann cells of nerve sheaths. Approximately three percent of schwannomas occur retroperitoneally, but renal involvement is uncommon [4]. Most of them are benign, and malignancy is rare. There are different types of schwannomas: plexiform, ancient, cellular, melanotic, epithelioid, and microcystic [5]. In the 2020 WHO Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissue, melanotic schwannoma was reclassified as a malignant tumor because of its aggressive clinical behavior [6].

There are only 37 cases of renal schwannoma reported in the English literature. Table 1 summarizes the data for these cases, including the present case. Among the 37 cases, the mean age of the patients was 52.0 ± 14.0 years (range 18–74 years), and the male to female ratio was 1:1.5. The mean size of the lesions was 8.0 ± 4.3 cm (range 2.6–20.5 cm). The renal schwannomas were all solitary. There were 16 lesions in the left kidney and 21 lesions in the right kidney, and the ratio of left to right was approximately 1:1.3. These lesions were located at the hilum and pelvis (51.4%), parenchyma (43.2%) and capsule (5.4%). Among all cases, 33 were benign, and 4 were malignant. Malignant renal schwannoma can metastasize to the lung, bone, diaphragm, liver, colon, mesentery, peritoneum, and subcutaneous tissues, of which lung metastasis is the most common.

We further analyzed the radiological images of these previously reported renal schwannomas and summarized some of its radiological features. On ultrasound (US), renal schwannomas are hypoechoic, well-defined masses and may contain cystic areas, which are more commonly seen in renal schwannomas, as they are larger than 5 cm. The larger the tumor is, the more cystic degeneration and necrosis are present. Further investigation is usually performed with CT or MR imaging. On nonenhanced CT, they are typically well-defined and round or fusiform hypoattenuating masses. Large tumors also show cystic degeneration, calcifications and hemorrhage. On contrast-enhanced CT, renal schwannomas show mild to moderate homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancement. On MR imaging, most renal schwannomas often appear isointense or hypointense relative to muscle on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging with variable enhancement; however, cystic degeneration and hemorrhage can complicate the signal intensity. In addition, pyelectasis and caliectasis on excretory and retrograde pyelography and hypovascular tumors on renal arteriography can be seen. There are no clear imaging features that can differentiate between benign and malignant lesions unless metastasis in other regions is found.

There are two important differences between the present case and the previous cases. First, the patient in question here had a large renal schwannoma, which is quite rare, making it the largest tumor reported thus far. Second, to the best of our knowledge, this case presents with more extensive bleeding and cystic degeneration than any of the previous reported cases. In our case, due to the large range of cystic lesions and hemorrhage, the mass was slightly hyperintense on T1-weighted imaging and had high-low mixed signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging with ring-like and septal enhancement.

The clinical symptoms of renal schwannoma are nonspecific; a small number of patients do not have any symptoms, and the mass is only found incidentally during physical examination for any number of reasons. Among the 37 previous cases, the most common symptoms were abdominal pain (51.4%, mostly flank pain), hematuria (21.6%) and fever (16.2%). Other symptoms included nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and weight loss. In our report, the patient exhibited persistent flank pain. As the tumor grew, it pressed on the surrounding organs and tissues, resulting in pain that worsened and caused dyspnea during emotional agitation and when lying in the supine position. In addition, renal schwannomas grow slowly. When the tumor grows to a certain volume, the abdominal mass can be palpated.

Radical nephrectomy or partial nephrectomy are recommended as first-line treatments for renal schwannomas. Histologically, a typical schwannoma consists of Antoni A and Antoni B tissue. Antoni A tissue is composed of spindle cells arranged in a palisade with Verocay bodies, while Antoni B tissue is composed of loose and scattered cells with many myxoid changes [33]. S-100 protein immunostaining was positive in all cases.

In conclusion, renal schwannomas are rare and grow slowly. Cystic degeneration in the tumor is a common imaging feature. When a middle aged-elderly patient has a well-defined renal tumor with obvious cystic degeneration and shows mild to moderate homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancement, renal schwannoma should be considered. However, pathological examination is the gold standard for diagnosis. We report a large renal schwannoma with obvious hemorrhage and cystic degeneration, which could be used as a reference for further study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- US:

-

Ultrasound

References

Zhang Z, Gong T, Rennke HG, Hayashi R. Duodenal schwannoma as a rare association with membranous nephropathy: a case report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73(2):278–80.

Guerreiro C, Dionisio J, Duro DCJ. Endobronchial schwannoma involving the carina. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53(8):452.

Verze P, Somma A, Imbimbo C, Mansueto G, Mirone V, Insabato L. Melanotic schwannoma: a case of renal origin. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2014;12(1):e37–41.

Gubbay AD, Moschilla G, Gray BN, Thompson I. Retroperitoneal schwannoma: a case series and review. Aust N Z J Surg. 1995;65(3):197–200.

Iannaci G, Crispino M, Cifarelli P, Montella M, Panarese I, Ronchi A, Russo R, Tremiterra G, Luise R, Sapere P. Epithelioid angiosarcoma arising in schwannoma of the kidney: report of the first case and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14(1):29.

Choi JH, Ro JY. The 2020 WHO Classification of tumors of soft tissue: selected changes and new entities. Adv Anat Pathol. 2021;28(1):44–58.

Phillips CA, Baumrucker G. Neurilemmoma (arising in the hilus of left kidney). J Urol. 1955;73(4):671–3.

Fein RL, Hamm FC. Malignant schwannoma of the renal pelvis: a review of the literature and a case report. J Urol. 1965;94(4):356–61.

Bair ED, Woodside JR, Williams WL, Borden TA. Perirenal malignant schwannoma presenting as renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 1978;11(5):510–2.

Steers WD, Hodge GB, Johnson DE, Chaitin BA, Charnsangavej C. Benign retroperitoneal neurilemoma without von Recklinghausen’s disease: a rare occurrence. J Urol. 1985;133(5):846–8.

Somers WJ, Terpenning B, Lowe FC, Romas NA. Renal parenchymal neurilemoma: a rare and unusual kidney tumor. J Urol. 1988;139(1):109–10.

Kitagawa K, Yamahana T, Hirano S, Kawaguchi S, Mikawa I, Masuda S, Kadoya M. MR imaging of neurilemoma arising from the renal hilus. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1990;14(5):830–2.

Ma KF, Tse CH, Tsui MS. Neurilemmoma of kidney—a rare occurrence. Histopathology. 1990;17(4):378–80.

Naslund MJ, Dement S, Marshall FF. Malignant renal schwannoma. Urology. 1991;38(5):477–9.

Romics I, Bach D, Beutler W. Malignant schwannoma of kidney capsule. Urology. 1992;40(5):453–5.

Singer AJ, Anders KH. Neurilemoma of the kidney. Urology. 1996;47(4):575–81.

Alvarado-Cabrero I, Folpe AL, Srigley JR, Gaudin P, Philip AT, Reuter VE, Amin MB. Intrarenal schwannoma: a report of four cases including three cellular variants. Mod Pathol. 2000;13(8):851–6.

Tsurusaki M, Mimura F, Yasui N, Minayoshi K, Sugimura K. Neurilemoma of the renal capsule: MR imaging and pathologic correlation. Eur Radiol. 2001;11(9):1834–7.

Cachay M, Sousa-Escandon A, Gibernau R, Benet JM, Valcacel JP. Malignant metastatic perirenal schwannoma. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2003;37(5):443–5.

Singh V, Kapoor R. Atypical presentations of benign retroperitoneal schwannoma: report of three cases with review of literature. Int Urol Nephrol. 2005;37(3):547–9.

Umphrey HR, Lockhart ME, Kenney PJ. Benign renal schwannoma: a case report and literature review. Radiol Case Rep. 2007;2(2):52–5.

Hung SF, Chung SD, Lai MK, Chueh SC, Yu HJ. Renal Schwannoma: case report and literature review. Urology. 2008;72(3):713–6.

Gobbo S, Eble JN, Huang J, Grignon DJ, Wang M, Martignoni G, Brunelli M, Cheng L. Schwannoma of the kidney. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(6):779–83.

Qiguang C, Zhe Z, Chuize K. Neurilemoma of the renal hilum. Am Surg. 2010;76(11):E197–8.

Nayyar R, Khattar N, Sood R, Bhardwaj M. Cystic retroperitoneal renal hilar ancient schwannoma: report of a rare case with atypical presentation masquerading as simple cyst. Indian J Urol. 2011;27(3):404–6.

Yang HJ, Lee MH, Kim DS, Lee HJ, Lee JH, Jeon YS. A case of renal schwannoma. Korean J Urol. 2012;53(12):875–8.

Wang Y, Zhu B. A case of schwannoma in kidney. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2013;3(3):180–1.

Mikkilineni H, Thupili CR. Benign renal schwannoma. J Urol. 2013;189(1):317–8.

Yong A, Kanodia AK, Alizadeh Y, Flinn J. Benign renal schwannoma: a rare entity. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;20:bcr2015211642.

Hall SJ, Williams ST, Jackson TA, Lee AT, McCulloch TA. Retroperitoneal gastrointestinal type schwannoma presenting as a renal mass. Urol Case Rep. 2015;3(6):206–8.

Kumano Y, Kawahara T, Chiba S, Maeda Y, Ohtaka M, Kondo T, Mochizuki T, Hattori Y, Teranishi J, Miyoshi Y, et al. Retroperitoneal schwannoma in the renal hilum: a case report. Case Rep Oncol. 2015;8(3):394–8.

Herden J, Drebber U, Ural Y, Zimmer S, Wille S, Engelmann UH. Retroperitoneal schwannomas of renal and pararenal origin: presentation of two case reports. Rare Tumors. 2015;7(1):5616.

Vidal CN, Lopez CP, Ferri NB, Aznar ML, Gomez GG. Benign renal schwannoma: case report and literature review. Urol Case Rep. 2020;28: 101018.

Wang C, Gao W, Wei S, Ligao W, Beibei L, Jianmin L, Xiaohuai Y, Yuanyuan G. Laparoscopic nephrectomy for giant benign renal schwannoma: a case report and review of literature. Aging Male. 2020;23(5):1504–8.

Dahmen A, Juwono T, Griffith J, Patel T. Renal schwannoma: a case report and literature review of a rare and benign entity mimicking an invasive renal neoplasm. Urol Case Rep. 2021;37: 101637.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research is supported by the People's Hospital of Yuechi County (Grant No. YY21-01,02), the affiliated hospital of north Sichuan medical college (Grant No. 2021LC004) and the opening project of medical imaging key laboratory of Sichuan province (Grant No. MIKLSP2021010). The funding bodies did not have anything to do with the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation or writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CFY composed the manuscript preparation. HZ provided figures. CFY, JHY, and YL had the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data. SKD and YL revised manuscript. All authors have reviewed the final version of the manuscript and approve it for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. A copy of the consent form is available for review and can be provided on request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, C.F., Zuo, H., Yu, J.H. et al. Giant renal schwannoma with obvious hemorrhage and cystic degeneration: a case report and literature review. BMC Urol 22, 101 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-022-01058-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-022-01058-9