Abstract

Background

Treating complex perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease patients remains a challenge. Classical surgical treatments for Crohn’s disease fistulas have been extrapolated from cryptoglandular fistulas treatment, which have different etiology, and this might interfere with its effectiveness, in addition, they increase fecal incontinence risk. Recently, new surgical techniques with support from biological approaches, like stem cells, have been developed to preserve the function of the sphincter. We have performed a systematic literature review to compare the results of these different techniques in the treatment of Crohn’s or Cryptoglandular fistula.

Methods

PubMed, EMBASE, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched systematically for relevant articles. We included randomized controlled trials and observational studies that referred to humans, were written in English, included adults 18+ years old, and were published during the 10-year period from 2/01/2010 to 2/29/2020. Evidence level was assigned as designated by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.

Results

Of the 577 citations screened, a total of 79 were ultimately included in our review. In Crohn’s disease patients, classical techniques such as primarily seton, Ligation of Intersphincteric Fistula Tracks, or lay open, healing rates were approximately 50–60%, while in cryptoglandular fistula were around, 70–80% for setons or flaps. In Crohn’s disease patients, new surgical techniques using derivatives of adipose tissue reported healing rates exceeding 70%, stem cells-treated patients achieved higher combined remission versus controls (56.3% vs 38.6%, p = 0.010), mesenchymal cells reported a healing rate of 80% at week 12. In patients with cryptoglandular fistulas, a healing rate of 70% using derivatives of adipose tissue or platelets was achieved, and a healing rate of 80% was achieved using laser technology. Fecal incontinence was improved after the use of autologous platelet growth factors and Nitinol Clips.

Conclusion

New surgical techniques showed better healing rates in Crohn’s disease patients than classical techniques, which have better results in cryptoglandular fistula than in Crohn’s disease. Healing rates for complex cryptoglandular fistulas were similar between the classic and new techniques, being the new techniques less invasive; the incontinence rate improved with the current techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The estimated incidence of perianal fistulas in Europe is 1.2–2.8 per 10,000 people [1,2,3]. Perianal fistulas appear in 30–50% of Crohn’s disease (CD) cases, and 80% of those fistulas are classified as complex [4, 5]. In this scenario, medical treatments are intended to promote long-term fistula healing, while preserving continence and avoiding diverting stomas [6]. However, these goals are often unmet with currently available therapies, particularly in relation to complex perianal fistulas, which are the most challenging to treat [7]. Treatment of complex perianal fistulas (CPF) in patients with CD is especially challenging for surgeons and gastroenterologists. Medical therapy is typically still recommended as a first line treatment, with surgery being reserved for sepsis control or laying open superficial tracks [8, 9].

During the last 30 years, many “classic” surgical techniques used to treat cryptoglandular complex perianal fistulas, such as core out, advancement flaps, or ligation of intersphincteric fistula tracks (LIFTs), have also been used to resolve CPF associated with CD [10]. However, during the last 10 years, a shift has occurred to a new and usually minimally invasive surgery (MIS), with support from biological approaches, such as stem cells, platelet rich plasma, or the use of fibrin or glue, to avoid touching the sphincter, hence preserving fecal continence.

The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review and audit of the results of complex perianal fistula surgeries for patients with CD or cryptoglandular fistulas. We performed this review to revisit the concept of perianal complex fistula treatments and answer questions concerning the clinical evidence that has emerged regarding various surgical approaches to CD and cryptoglandular complex perianal fistulas, in terms of fistula healing, Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), cost, and fecal continence.

Methods

Review design

The protocol (stored in PORIB) and reporting methodology for this systematic review was designed in accordance with the PRISMA-P guidelines [11]. The participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICO) strategy was followed to identify the populations (CPF in patients with CD or fistulas of cryptoglandular origin), intervention (surgery), comparisons (clinical trials or observational studies), and outcomes (clinical, economic, and quality of life) (Additional file 1).

Eligibility criteria

We included all the primary studies published in the medical literature related to the clinical outcomes, quality of life, or economic costs of complex perianal fistula surgeries for patients with CD or cryptoglandular-associated fistulas not related to CD. The eligible studies included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies that referred to humans, were written in English, included adults 18+ years old, and were published in the 10-year period from 2/01/2010 to 2/29/2020. We excluded articles regarding a different population (Reason 1), type of fistula such as simple fistulas, internal fistulas, such as rectovaginal, anovaginal, rectourethral, or ileovaginal fistulas (Reason 2), non-surgical interventions, such as pharmacological or medical treatments (Reason 3), type of study such as reviews (Reason 4) and publications without clinical outcome, quality of life, or cost results (Reason 5).

Data sources and search strategy

In March 2020, a literature search strategy was designed using variations on the search terms “Crohn’s disease”, “Rectal fistula”, “Perianal”, “Fistulizing disease”, “Complex”, “Inflammatory Bowel Disease”, “Cryptoglandular”, “Surgical intervention”, and “Surgical procedures”. The following databases were searched: PubMed, EMBASE, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). We also searched the 2018–2020 abstract books for the European Society of Coloproctology (ESCP), European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO), United European Gastroenterology (UEG) Week, American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), and the American Society of Colon & Rectal Surgeons. The search strategy is shown in Additional file 2.

Study selection and data extraction

Two reviewers independently reviewed each citation against our eligibility criteria in the following 2-stage process: (1) title and abstract and (2) full text. During the study selection and data extraction stages, disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussion or with a decision made by a third researcher.

Quality assessment

Each article was assigned one of the following quality of study scores, as designated by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) [12], according to the level of evidence provided in the paper:

-

1++: High quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with an extremely low risk of bias

-

1+: Well-conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews, or RCTs with a low risk of bias Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, or RCTs with a high risk of bias

-

2++: High quality systematic reviews of case control or cohort studies.

-

High quality case control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding factors or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causal.

-

2+: Well-conducted case control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding factors or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal.

-

Case control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding factors or bias and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal.

-

3: Non-analytic studies, e.g. case reports, case series.

-

4: Expert opinions.

We extracted the intervention, study design, number of patients, and main conclusions from each selected article and added the 2019 impact factor from the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) to provide more information for the qualitative analysis.

Results

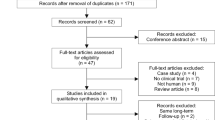

We identified 577 citations from PubMed, EMBASE, DARE, and CENTRAL, and 32 records from other sources (Fig. 1). After removing duplicate papers (75 papers), the titles and abstracts of 502 citations were screened, from which 342 were excluded. Subsequently, the full text of 160 citations was retrieved and assessed for inclusion. Eighty studies were finally retained. No additional studies were identified through tracking citations or by manually reviewing the references of included studies.

We split the results into two categories, i.e., CD-associated CPF and CPF of cryptoglandular origin. We also differentiated between MIS and classic surgical techniques. The clinical results are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

We found that the concepts of healing and fecal incontinence were defined differently in the various studies, making quantitative aggregation difficult; therefore, these issues must be considered when interpreting our results. Nevertheless, we were still able to obtain relevant information from the review.

Clinical outcomes

Of the 18 articles with clinical results that referred to CD, 4 reported level 1 evidence, one reported level 2 evidence, and 10 reported level 3 evidence. A total of 15 articles referred to MIS techniques, and three referred to classical techniques. Studies referring to the most current techniques were more common than those referring to traditional techniques, the evidence levels presented for the current techniques were higher, and the results were more favorable. Two studies employing treatments using derivatives of adipose tissue reported healing rates exceeding 70% [15, 25], and a significantly greater proportion of patients stem cells-treated achieved combined remission versus controls (56.3% vs 38.6%, p = 0.010) in a high-level evidence study [14]. In a study investigating a treatment using mesenchymal cells, in which healing was defined as fistula absence or less than 2 cm discharge on magnetic resonance imaging, the authors reported a healing rate of 80% at week 12 [20]. In a pilot study with 10 patients undergoing fistulectomies with platelet-rich plasma, one (10%) patient experienced a recurrence, and two (20%) patients had persistent fistulas after treatment. In two studies examining classical techniques (primarily seton, LIFT, or lay open), the healing rates were approximately 50–60% [28, 29]. Graf et al. observed that 62 (52%) patients achieved healing (absence of fistula symptoms, skin healing, and no evidence of a fistula on clinical examination) by the end of the follow-up period, but only 14 of the patients had healed after a single procedure, while the remaining 48 healed after a median of 4.0 (2–20) additional procedures [28].

Of the 52 references referring to clinical results for patients with fistulas of cryptoglandular origin, three of the articles reported level 1 evidence, six reported level 2 evidence, and 43 reported level 3 evidence. A total of 28 articles referred to MIS (25 articles reported the use of plugs), and 24 articles referred to classic techniques (six articles reported the use of seton, and four studies incorporated flaps). The MIS studies reported healing rates between 50% and 90%; a healing rate of 70% was reported for a study using derivatives of adipose tissue [42], an 80% healing rate was achieved using laser technology [51], a 70% healing rate was achieved using platelets [31], and healing rates between 50% and 90% were achieved using various plugs [34, 38, 41]. Additionally, each of these studies presented results for various other aspects of complex perianal fistulas, such as pain, quality of life, or continence; continence was most frequently reported in these studies, and improved results were typical. Decreases in Wexner scores after the use of autologous platelet growth factors [36] and Nitinol Clips [38] were also reported. No fecal incontinence was reported after procedures performed with over-the-scope-clips [41] or stem cells derived from autologous adipose tissue [42]. Recurrence and retreatment occurred in 2/10 cases [44] and 20/25 cases [45] using two kinds of plugs.

For some studies that incorporated classic techniques, the healing percentages were similar to those observed in the MIS studies (70–80% for setons [60] or flaps [61] and somewhat lower percentages for other techniques, such as a fistulotomies or fistulectomies [23, 40]); however, the overall function in these patients was lower, as more cases of incontinence were reported, either because the incontinence was not corrected or it appeared de novo. In a study investigating fistulotomies, only 26.3% of the patients had a perfect continence state, with a Vaizey score equal to 0 [74]. The recurrence or retreatment rates in these studies varied from 5.9 to 50% [62, 66, 67].

HRQoL outcomes

Four HRQoL studies in this analysis were performed for CD, but only one of them showed a relationship between the results and the surgical technique used. In a post-hoc analysis of the ADMIRE-CD clinical trial, Panes et al. [83] observed that patients who experienced clinical or combined remission had lower (Perianal Disease Activity Index) PDAI scores for pain and discharge than those who did not experience remission. The scores were fourfold higher for patients who experienced clinical or combined remission in combination with magnetic resonance imaging. The scores were fourfold higher for patients who experienced clinical or combined remission in combination with magnetic resonance imaging. Other HRQoL studies referred to abdominal surgery [84] or perianal disease [85, 86] in general, so they did not refer to surgery.

Three studies with HRQoL outcomes for patients with cryptoglandular CPF were included in this review. Jayne et al. [87] compared the efficacy of the Surgisis anal fistula plug with various other techniques in a prospective, multicenter, randomized, unblinded, parallel arm clinical trial. A total of 304 patients were included in their study, and the authors observed no differences in the clinical healing rates (55%, 64%, 75%, 53%, and 42% for the fistula plug, seton cut, fistulotomy, advancement flap, and LIFT procedure, respectively) at 12 months. The baseline fecal incontinence rates were lower for the groups with little improvement after treatment. The mean total costs were £2738 (± £1.151) for the fistula plug group and £2308 (± £1.228) for the surgeon’s preference group. The Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) were higher for the fistula plug group (0.829 ± 0.174) than for the surgeon’s preference group (0.790 ± 0.212), which establishes that there is a 35–45% chance that the fistula plug is as profitable as the surgeon’s preference for an availability to pay range of £20,000–30,000/QALY.

In a prospective study of 34 patients undergoing surgical treatment, Jayarajah [88] reported overall preoperative and postoperative incontinence rates of 18% and 38%, respectively. The total mean Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life (FIQL) score was 16.0 (Standard Deviation, SD ± 0.4) preoperatively and 16.1 (SD ± 0.4) postoperatively. The authors also observed a considerable difference in the scale that measures “depression/self-perception” before and after the intervention (p = 0.012). In a retrospective cross-sectional study, Visscher et al. [89] found that by the end of the follow-up period (mean follow-up of 7.8 years) 39/141 patients (34%) who underwent unspecified surgical procedures after an initial perianal fistula surgery still experienced incontinence. Surgical fistulotomies, drainage of multiple abscesses, and high transsphincteric or suprasphincteric abscesses were associated with incontinence to a significant degree. Incontinence was worse for patients who had surgery for CPF (Wexner score, 4.7 ± 6.2) than for those who had surgery for simple fistulas (Wexner score, 1.2 ± 2.1) (p = 0.001). Surgery for CPF was also associated with worse quality of life outcomes, including lifestyle (p = 0.030), depression (p = 0.077), and shame (p < 0.001).

Cost outcomes

Of the articles included in this review, only the Jayne et al. article [87] associated a technique with its economic cost. In this study, a mean total cost was associated with the group who underwent treatment with fistula plugs (£2738 ± £1151) and the rest of the treatments (£2308 ± £1228). Additionally, a QALY gain of 0.829 ± 0.174 was calculated for the group with fistula plugs compared to 0.790 ± 0.212 for the surgeon’s preference group (0.790 ± 0.212). The probabilistic incremental cost-effectiveness results were £10,993 (± £478,666), with a 35–45% chance that the fistula plug is as profitable as the surgeon’s preference for an availability-to-pay range of £20,000–30,000/QALY. Three studies showed the cost of CD, but none showed the cost of any surgical techniques [90,91,92].

Discussion

We conducted a comprehensive systematic literature review to audit the clinical outcomes resulting from surgical treatment of complex perianal fistulas. Various databases and sources of information were analyzed to determine the similarities between surgical treatments for CD-associated fistulas and cryptoglandular complex perianal fistulas. Studies by Graf [28], Gingold [29], and Galis-Rozen [30] showed that classic techniques, such as lay open, LIFT, fistulectomies, and flaps, are still used to treat CD, despite the potential risk of exposure to the anal sphincter. The communicated healing percentage for CD was approximately 50% usually after the repeated procedures [28, 30], and the percentage of patients with incontinence rose to 60% (9/15) by the end of the follow-up period [29]. These results were surpassed decisively by those for MIS, a difference of 17% in remission rates was reported in stem cells-treated patients in a clinical trial [14] and healing rates close to 80%, with a reduction in the PDAI and improvements to the HRQoL in some patient series’ [13]. In a study with autologous adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction a significant reduction in the severity of perianal disease was shown, with PDAI reduction from 7.3 to 3.4 in week 48 (p = 0.045). According to Tozer et al. [93] we hypothesize that the inflammatory origin present in the CD fistula prevents its complete healing with conventional techniques. Therefore, the use of cellular mechanisms with anti-inflammatory potential may have a favorable result in healing and maintaining sphincter function beyond the use of a single conventional technique. However, these conclusions must be ratified in subsequent studies, since the studies published up to the date of the review sometimes corresponded to series with few patients and a short follow-up period.

In CPF results on healing rate were similar between MIS and classic techniques. In MIS we found that in a study with OTSC device® (over-the-scope-clip) [34] there was no appearance of fecal incontinence, an improvement of Wexner score with the use of autologous platelet growth factors, from 3.0625 to 1.125 in a year, p = 0.0195 [35]; no deterioration of continence was observed with Nitinol Clip [38] as a result of the last 5 years. In classic techniques we found a study with a slight continence deficit in patients treated with Mucosal advancement flap [61], no improvement in continence was reported by Balciscueta et al. [62], and cases of fecal incontinence were detected as complications in 8 patients treated with seton [64].

We observed that during the 10-year period from 02/01/2010 to 02/29/2020, a shift occurred in the treatment of cryptoglandular CPF from classic surgical techniques to a MIS/biological approach; this shift has allowed better facilitation of the healing and preservation of sphincter function. Of the 18 papers that referred to CD, 13 reported on investigations regarding MIS, and four reported on classic techniques. We found that there was not a significant difference between the number of articles for each of the procedures, as there were 27 articles referring to MIS and 22 referring to classic techniques. Therefore, we suggest that a paradigm shift is beginning to occur, making MIS a first order treatment for CPF of cryptoglandular origin.

Notably, procedures like LIFT are recommended in some guidelines as a first option for patients with CD [94], although this is not supported by substantial evidence, as we found only one reference that advocated for this recommendation [29]. Therefore, we suggest that these recommendations should be reevaluated. Given what has been published, we believe that it is safer not to divide any part of the anal sphincter when treating perianal CD.

A critical point in the topic we are dealing with is the use of new pharmacological treatments such as anti-TNF for the management of patients with CD fistula. Although the objective of our study was to analyze the surgical techniques and pharmacological treatments that were excluded, we believe that it is appropriate to highlight this aspect. Treatment with infliximab indeed has good results in these patients, but it is also true that after 1 year of treatment the response rate can fall to 23% [95]. These results have recently been improved with the use of mesenchymal cells with annual response rates of 59% [96].

Nevertheless, these initial observations must be analyzed with consideration for the following limitations: First, our preliminary hypothesis was that the level of evidence from the selected studies could be low, and this would create a high risk of bias. The selected articles have confirmed this hypothesis, especially in the case of the articles about classic procedures. This made it difficult to carry out a more rigorous comparison of the results, such as meta-analysis or network meta-analysis. The different ways to present healing and continence results also made it difficult to aggregate the results.

We determined that there are no published studies that have specifically investigated the relationship between surgical techniques and quality of life. Therefore, we suggest that studies capable of determining the impact of the various surgical procedures from the patient’s perspective should be designed, as the HRQoL is only a secondary or tertiary variable in currently published studies. Only 6 of the 80 (7.5%) total references (Serrero, both in 2017 [15] and 2019 [13], Gingold [29], El-Said [59], Gottgens [74], and Herreros [48]) reported quality of life results. Consequently, we encourage the development of robust quality of life and cost-effectiveness studies, as both these variables are factored into our conclusions.

In conclusion, our review shows that patients with CD experience a higher rate of healing after MIS techniques than patients who undergo classic surgical techniques, and the healing rate for complex anal fistulas with cryptoglandular origins appears similar between classic and minimally invasive techniques. Additionally, the incontinence rate for patients that undergo minimally invasive surgical techniques is better than that of patients who undergo classic techniques. Therefore, we recommend moving to MIS-based techniques, in conjunction with new biological technologies like stem cells, plugs or Adipose-Derived Stromal Vascular Fraction use, because these techniques seem to be supported by recently published clinical evidence.

Availability of data and materials

The search strategy is shown in Additional file 2, results of the search are stored in PORIB.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse Effects

- AGA:

-

American Gastroenterological Association

- CD:

-

Crohn’s Disease

- CDAI:

-

Crohn Disease Activity Index

- CENTRAL:

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- CPF:

-

Complex Perianal Fistulas

- DARE:

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness

- ECCO:

-

European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation

- ESCP:

-

European Society of Coloproctology

- FIQL:

-

Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life

- HR:

-

Hazard Ratio

- HRQoL:

-

Health-Related Quality of Life

- IF:

-

Impact Factor

- JCR:

-

Journal Citation Reports

- LIFT:

-

Ligation of Intersphincteric Fistula Tracks

- MIS:

-

Minimally Invasive surgery

- MMC:

-

Mesenchymal Mother Ccells

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- PDAI:

-

Perianal Disease Activity Index

- PICO:

-

Participants, Interventions, Comparisons, Outcomes, and Study Design

- QALYs:

-

Quality Adjusted Life Years

- RCT:

-

Randomized Controlled Trials

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- SIGN:

-

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network

- UEG:

-

United European Gastroenterology

References

Zanotti C, Martinez-Puente C, Pascual I, Pascual M, Herreros D, García-Olmo D. An assessment of the incidence of fistula-in-ano in four countries of the European Union. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1459–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-007-0334-7.

Vogel JD, Johnson EK, Morris AM, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of anorectal abscess, fistula-in-ano, and rectovaginal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:1117–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000733.

García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, Tagarro I, Diez MC, Richard MP, Mona J. Prevalence of anal fistulas in Europe: systematic literature reviews and population-based database analysis. Adv Ther. 2019;36:3503–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01117-y.

Eglinton TW, Barclay ML, Gearry RB, et al. The spectrum of perianal Crohn’s disease in a population-based cohort. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:773–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e31825228b0.

Bell SJ, Williams AB, Wiesel P, et al. The clinical course of fistulating Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1145–51. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01561.x.

Gecse KB, Bemelman W, Kamm MA, et al. A global consensus on the classification, diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment of perianal fistulising Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2004;63(9):1381–92. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306709.

Schwartz DA, Herdman CR. Review article: the medical treatment of Crohn’s perianal fistulas. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:953–67.

Steele SR, Kumar R, Feingold DL, Rafferty JL, Buie WD. Practice parameters for the management of perianal abscess and fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1465–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823122b3.

Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W, et al. The second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: special situations. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2010;4:63–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2009.09.009.

Blumetti J, Abcarian A, Quinteros F, Chaudhry V, Prasad L, Abcarian H. Evolution of treatment of fistula-in-ano. World J Surg. 2012;36:1162–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-012-1480-9.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). SIGN grading system 1999–2012. 2012. https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/sign_grading_system_1999_2012.pdf. Accessed 12 Feb 2020.

Serrero M, Grimaud F, Philandrianos C, Visée C, Sabatier F, Grimaud JC. Long-term safety and efficacy of local microinjection combining autologous microfat and adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction for the treatment of refractory perianal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(8):2335–7. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.032.

Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(5):1334-1342.e4. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.020.

Serrero M, Philandrianos C, Visee C, Veran J, Orsoni P, Sabatier F. An innovative treatment for refractory perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: local micro reinjection of autologous fat and adipose derived stromal vascular fraction. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2017;11:S5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx002.007.

Wilhelm A, Fiebig A, Krawczak M. Five years of experience with the FiLaC™ laser for fistula-in-ano management: long-term follow-up from a single institution. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21(4):269–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-017-1599-7.

Dietz AB, Dozois EJ, Fletcher JG, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells, applied in a bioabsorbable matrix, for treatment of perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):59-62.e2. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.001.

Hermann J, Banasiewicz T, Kołodziejczak B. Role of vacuum-assisted closure in the management of Crohn anal fistulas. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2019;32(1):35–40.

Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, Colombel JF, Reinisch W, Baumgart D. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1281–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31203-X.

Molendijk I, Bonsing BA, Roelofs H, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells promote healing of refractory perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(4):918–27. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.014.

Senéjoux A, Siproudhis L, Abramowitz L, Munoz-Bongrand N, Desseaux K, Bouguen G. Fistula plug in fistulising ano-perineal Crohn’s disease: a randomised controlled trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(2):141–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv162.

Park KJ, Ryoo SB, Kim JS, et al. Allogeneic adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of perianal fistula in Crohn’s disease: a pilot clinical trial. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18(5):468–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13223.

Göttgens KW, Smeets RR, Stassen LP, Beets GL, Pierik M, Breukink SO. Treatment of Crohn’s disease-related high perianal fistulas combining the mucosa advancement flap with platelet-rich plasma: a pilot study. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19(8):455–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-015-1311-8.

Cho YB, Lee WY, Park KJ, Kim M, Yoo HW, Yu CS. Autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cells for the treatment of Crohn’s fistula: a phase I clinical study. Cell Transplant. 2013;22(2):279–85. https://doi.org/10.3727/096368912X656045.

Lee WY, Park KJ, Cho YB, et al. Autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cells treatment demonstrated favorable and sustainable therapeutic effect for Crohn’s fistula. Stem Cells. 2013;31(11):2575–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.1357.

de la Portilla F, Alba F, García-Olmo D, Herrerías J, González FX, Galindo A. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived stem cells (eASCs) for the treatment of complex perianal fistula in Crohn’s disease: results from a multicenter phase I/IIa clinical trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28(3):313–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-012-1581-9.

Ciccocioppo R, Bernardo ME, Sgarella A, Maccario R, Avanzini MA, Ubezio C. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in the treatment of fistulising Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2011;60(6):788–98. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.214841.

Graf W, Andersson M, Åkerlund JE, Börjesson L, Swedish Organization for Studies of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Long-term outcome after surgery for Crohn’s anal fistula. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18(1):80–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13106.

Gingold DS, Murrell ZA, Fleshner PR. A prospective evaluation of the ligation of the intersphincteric tract procedure for complex anal fistula in patients with Crohn’s disease. Ann Surg. 2014;260(6):1057–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000479.

Galis-Rozen E, Tulchinsky H, Rosen A, et al. Long-term outcome of loose setón for complex anal fistula: a two-centre study of patients with and without Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(4):358–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01796.x.

de la Portilla F, Durán MV, Maestre MV, García-Cabrera AM, Reyes ML, Vázquez-Monchul JM. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) versus fibrin glue in cryptogenic fistula-in-ano: a phase III single-center, randomized, double-blind trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34(6):1113–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-019-03290-6.

Dozois EJ, Lightner AL, Mathis KL, et al. Early results of a phase I trial using an adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell-coated fistula plug for the treatment of transsphincteric cryptoglandular fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(5):615–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000001333.

di Visconte MS, Bellio G. Comparison of porcine collagen paste injection and rectal advancement flap for the treatment of complex cryptoglandular anal fistulas: a 2-year follow-up study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33(12):1723–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-018-3154-z.

Marinello F, Kraft M, Ridaura N, Vallribera F, Espín E. Tratamiento de la fístula anal mediante clip con el dispositivo OTSC®: resultados a corto plazo [Treatment of fistula-in-ano with OTSC® proctology clip device: short-term results]. Cir Esp. 2018;96(6):369–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2018.02.003.

Schniewind B, Schafmayer C, von Schönfels W, et al. Treatment of complicated anal fistula by an endofistular polyurethane-sponge vacuum therapy: a pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(12):1435–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000001233.

de la Portilla F, Segura-Sampedro JJ, Reyes-Díaz ML, Maestre MV, Cabrera AM, Jimenez-Rodríguez RM. Treatment of transsphincteric fistula-in-ano with growth factors from autologous platelets: results of a phase II clinical trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(11):1545–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-017-2866-9.

Choi S, Ryoo SB, Park KJ, et al. Autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cells for the treatment of complex perianal fistulas not associated with Crohn’s disease: a phase II clinical trial for safety and efficacy. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21(5):345–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-017-1630-z.

Nordholm-Carstensen A, Krarup PM, Hagen K. Treatment of complex fistula-in-ano with a nitinol proctology clip. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(7):723–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000831.

Giordano P, Sileri P, Buntzen S, et al. A prospective multicentre observational study of Permacol collagen paste for anorectal fistula: preliminary results. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18(3):286–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13112.

Ratto C, Litta F, Donisi L, Parello A. Prospective evaluation of a new device for the treatment of anal fistulas. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(30):6936–43. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i30.6936.

Prosst RL, Joos AK, Ehni W, Bussen D, Herold A. Prospective pilot study of anorectal fistula closure with the OTSC proctology. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17(1):81–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12762.

Borowski DW, Gill TS, Agarwal AK, Tabaqchali MA, Garg DK, Bhaskar P. Adipose tissue-derived regenerative cell-enhanced lipofilling for treatment of cryptoglandular fistulae-in-ano: the ALFA technique. Surg Innov. 2015;22(6):593–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/1553350615572656.

Stamos MJ, Snyder M, Robb BW, et al. Prospective multicenter study of a synthetic bioabsorbable anal fistula plug to treat cryptoglandular transsphincteric anal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(3):344–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000288.

Ozturk E. Treatment of recurrent anal fistula using an autologous cartilage plug: a pilot study. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19(5):301–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-015-1299-0.

Tan KK, Kaur G, Byrne CM, Young CJ, Wright C, Solomon MJ. Long-term outcome of the anal fistula plug for anal fistula of cryptoglandular origin. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(12):1510–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.12391.

Almeida IS, Wickramasinghe D, Weerakkody P, Samarasekera DN. Treatment of fistula in-ano with fistula plug: experience of a tertiary care centre in South Asia and comparison of results with the West. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):513. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3641-x.

Heydari A, Attinà GM, Merolla E, Piccoli M, Fazlalizadeh R, Melotti G. Bioabsorbable synthetic plug in the treatment of anal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(6):774–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182839824.

Herreros MD, Garcia-Arranz M, Guadalajara H, De-La-Quintana P, Garcia-Olmo D, FATT Collaborative Group. Autologous expanded adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of complex cryptoglandular perianal fistulas: a phase III randomized clinical trial (FATT 1: fistula advanced therapy trial 1) and long-term evaluation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(7):762–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e318255364a.

Ommer A, Herold A, Joos A, Schmidt C, Weyand G, Bussen D. Gore BioA fistula plug in the treatment of high anal fistulas–initial results from a German multicenter-study. Ger Med Sci. 2012. https://doi.org/10.3205/000164.

Cintron JR, Abcarian H, Chaudhry H, Singer M, Hunt S, Birnbaum E. Treatment of fistula-in-ano using a porcine small intestinal submucosa anal fistula plug. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17(2):187–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-012-0897-3.

Wilhelm A. A new technique for sphincter-preserving anal fistula repair using a novel radial emitting laser probe. Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15(4):445–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-011-0726-0.

Van der Hagen SJ, Baeten CG, Soeters PB, Van Gemert WG. Staged mucosal advancement flap versus staged fibrin sealant in the treatment of complex perianal fistulas. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011;2011: 186350. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/186350.

van der Hagen SJ, Baeten CG, Soeters PB, van Gemert WG. Autologous platelet-derived growth factors (platelet-rich plasma) as an adjunct to mucosal advancement flap in high cryptoglandular perianal fistulae: a pilot study. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(2):215–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01991.x.

El-Gazzaz G, Zutshi M, Hull T. A retrospective review of chronic anal fistulae treated by anal fistulae plug. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(5):442–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01802.x.

Lenisa L, Espìn-Basany E, Rusconi A, et al. Anal fistula plug is a valid alternative option for the treatment of complex anal fistula in the long term. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25(12):1487–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-010-0957-y.

Owen G, Keshava A, Stewart P, et al. Plugs unplugged. Anal fistula plug: the concord experience. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80(5):341–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05278.x.

Queralto M, Portier G, Bonnaud G, Chotard JP, Cabarrot P, Lazorthes F. Efficacy of synthetic glue treatment of high crypoglandular fistula-in-ano. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34(8–9):477–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gcb.2009.12.010.

McGee MF, Champagne BJ, Stulberg JJ, Reynolds H, Marderstein E, Delaney CP. Tract length predicts successful closure with anal fistula plug in cryptoglandular fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(8):1116–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181d972a9.

El-Said M, Emile S, Shalaby M, et al. Outcome of modified Park’s technique for treatment of complex anal fistula. J Surg Res. 2019;235:536–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.10.055.

Daodu O, O’Keefe J, Heine JA. Draining setons as definitive management of fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(4):499–503. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000001045.

Podetta M, Scarpa CR, Zufferey G, et al. Mucosal advancement flap for recurrent complex anal fistula: a repeatable procedure [published correction appears in Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018 Dec 20]. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34(1):197–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-018-3155-y.

Balciscueta Z, Uribe N, Mínguez M, García-Granero E. The changes in resting anal pressure after performing full-thickness rectal advancement flaps. Am J Surg. 2017;214(3):428–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.01.013.

Boenicke L, Karsten E, Zirngibl H, Ambe P. Advancement flap for treatment of complex cryptoglandular anal fistula: prediction of therapy success or failure using anamnestic and clinical parameters. World J Surg. 2017;41(9):2395–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4006-7.

Emile SH, Elfeki H, Thabet W, et al. Predictive factors for recurrence of high transsphincteric anal fistula after placement of seton. J Surg Res. 2017;213:261–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2017.02.053.

Sugrue J, Mantilla N, Abcarian A, et al. Sphincter-sparing anal fistula repair: are we getting better? Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(10):1071–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000885.

Herold A, Ommer A, Fürst A, et al. Results of the Gore Bio-A fistula plug implantation in the treatment of anal fistula: a multicentre study. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(8):585–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-016-1505-8.

Seow-En I, Seow-Choen F, Koh PK. An experience with video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT) with new insights into the treatment of anal fistulae. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(6):389–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-016-1450-6.

Visscher AP, Schuur D, Slooff RAE, Meijerink WJHJ, Deen-Molenaar CBH, Felt-Bersma RJF. Predictive factors for recurrence of cryptoglandular fistulae characterized by preoperative three-dimensional endoanal ultrasound. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18(5):503–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13211.

Raslan SM, Aladwani M, Alsanea N. Evaluation of the cutting setón as a method of treatment for perianal fistula. Ann Saudi Med. 2016;36(3):210–5. https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.2016.210.

Rosen DR, Kaiser AM. Definitive seton management for transsphincteric fistula-in-ano: harm or charm? Colorectal Dis. 2016;18(5):488–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13120.

Soliman F, Sturgeon G, Hargest R. Revisiting an ancient treatment for transphincteric fistula-in-ano ‘there is nothing new under the sun’ Ecclesiastes 1v9. J R Soc Med. 2015;108(12):482–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076815588322.

Lee CL, Lu J, Lim TZ, et al. Long-term outcome following advancement flaps for high anal fistulas in an Asian population: a single institution’s experience. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30(3):409–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-014-2100-y.

Uribe N, Balciscueta Z, Mínguez M, et al. “Core out” or “curettage” in rectal advancement flap for cryptoglandular anal fistula. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30(5):613–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-015-2133-x.

Göttgens KWA, Janssen PTJ, Heemskerk J, van Dielen FMH, Konsten FMH, Lettinga T. Long-term outcome of low perianal fistulas treated by fistulotomy: a multicenter study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30(2):213–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-014-2072-y.

Patton V, Chen CM, Lubowski D. Long-term results of the cutting setón for high anal fistula. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85(10):720–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.13156.

Hirschburger M, Schwandner T, Hecker A, Kierer W, Weinel R, Padberg W. Fistulectomy with primary sphincter reconstruction in the treatment of high transsphincteric anal fistulas. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29(2):247–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-013-1788-4.

Ratto C, Litta F, Parello A, Zaccone G, Donisi L, Simone V. Fistulotomy with end-to-end primary sphincteroplasty for anal fistula: results from a prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(2):226–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e31827aab72.

van Onkelen RS, Gosselink MP, Schouten WR. Treatment of anal fistulas with high intersphincteric extension. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(8):987–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182908be6.

Wallin UG, Mellgren AF, Madoff RD, Goldberg SM. Does ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract raise the bar in fistula surgery? Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(11):1173–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e318266edf3.

Abbas MA, Jackson CH, Haigh PI. Predictors of outcome for anal fistula surgery. Arch Surg. 2011;146(9):1011–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2017.104.

Mitalas LE, van Wijk JJ, Gosselink MP, Doornebosch P, Zimmerman DD, Schouten WR. Seton drainage prior to transanal advancement flap repair: useful or not? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25(12):1499–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-010-0993-7.

Roig JV, García-Armengol J, Jordán JC, Moro D, García-Granero E, Alós R. Fistulectomy and sphincteric reconstruction for complex cryptoglandular fistulas. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(7 Online):e145–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02002.x.

Panés J, García-Olmo D, Parfionovas A, Agboton C, Khalid JM. Patient-reported improvements in pain and discharge on the perianal disease activity index correlate with objective assessments of perianal fistula remission in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2019;154(6):S-383. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(18)31580-4.

Hotokezaka M, Ikeda T, Uchiyama S, Hayakawa S, Nakao H, Chijiiwa K. Factors influencing quality of life after abdominal surgery for Crohn’s disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59(118):1814–8.

Mahadev S, Young J, Selby W, Solomon M. Quality of life in perianal Crohn’s disease: what do patients consider important? Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(5):579–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/DCR.0b013e3182099d9e.

Mahadev S, Young JM, Selby W, Solomon MJ. Self-reported depressive symptoms and suicidal feelings in perianal Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(3):331–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02613.x.

Jayne DG, Scholefield J, Tolan D, Gray R, Edlin R, Hulme CT, et al. Anal fistula plug versus surgeon’s preference for surgery for trans-sphincteric anal fistula: the FIAT RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2019;23(21):1. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta23210.

Jayarajah U, Wickramasinghe DP, Samarasekera DN. Anal incontinence and quality of life following operative treatment of simple cryptoglandular fistula-in-ano: a prospective study. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):572. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2895-z.

Visscher AP, Schuur D, Roos R, Van der Mijnsbrugge GJH, Meijerink WH, Felt-Bersma RJ. Long-term follow-up after surgery for simple and complex cryptoglandular fistulas: fecal incontinence and impact on quality of life. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(5):533–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000352.

Chaparro M, Zanotti C, Burgueño P, et al. Health care costs of complex perianal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(12):3400–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-013-2830-7.

Martín-Arranz MD, Pascual Migueláñez I, Marijuán JL. Costs associated with the management of refractory complex perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) Congress. Copenhagen. 6-9/03/2019.

Nordholm-Carstensen A, Qvist N, Højgaard B, Halling C, Carstensen M, Ipland NP, Burisch J. Prevalence and healthcare costs of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease in a nationwide cohort. European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) Congress. Copenhagen. 6-9/03/2019.

Tozer PJ, Lung P, Lobo AJ, Sebastian S, Brown SR, Hart AL. Review article: pathogenesis of Crohn’s perianal fistula-understanding factors impacting on success and failure of treatment strategies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48(3):260–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14814.

Adamina M, Bonovas S, Raine T, Spinelli A, Warusavitarne J, Armuzzi A. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn’s disease: surgical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(2):155–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz187.

Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG. Fedorak RN, infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(9):876–85. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa030815.

Guadalajara H, García-Arranz M, Herreros MD, Borycka-Kiciak K, Lightner AL, García-Olmo D. Mesenchymal stem cells in perianal Crohn’s disease. Tech Coloproctol. 2020;24(8):883–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-020-02250-5.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank María Yébenes and Miguel Angel Casado for their collaboration during this project, as well as Editage (www.editage.com) for the English language editing. This manuscript is not based on a previous communication to a society or meeting.

Funding

Takeda Farmacéutica España S.A has funded the entire project and has participated in the concept and supervision of the study and in reviewing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DGO, MGB and FP have made substantial contributions to the conception, design of the work, interpretation of data and drafted and revised the work. DGO, MGB and FP have approved the submitted version and have agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work have been investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable, it is a systematic review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MGB develop their professional activity at PORIB, a consulting firm specialized in the economic evaluation of health technologies that has received remuneration from Takeda Farmacéutica España S.A., Spain for the realization of this project. Remuneration was not received for participation as an author during manuscript development. DGO and FP have received fees for conferences and educational activities of Takeda Farmacéutica España S.A. DGO, MGB and FP declare that the financial support has not interfered with the development of the work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA checklist. The results of PRISMA checklist are shown in the next tables.

Additional file 2.

Search strategy. The details of the search are listed in the next table.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

García-Olmo, D., Gómez-Barrera, M. & de la Portilla, F. Surgical management of complex perianal fistula revisited in a systematic review: a critical view of available scientific evidence. BMC Surg 23, 29 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-023-01912-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-023-01912-z