Abstract

Background

Extramedullary intracardiac multiple myeloma (MM) is extremely rare. Patients with extramedullary intracardiac MM may suffer from a poor prognosis. Experience in the diagnosis and therapy of cardiac involvement in MM is limited. Herein, we describe a 67-year-old male with extramedullary intracardiac MM who was initially misdiagnosed with a thrombus.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old male was admitted for exertional dyspnea and fatigue. The patient was diagnosed with MM one year earlier and had complete remission after chemotherapy. He was implanted with a permanent pacemaker two months prior due to sick sinus syndrome. After this admission, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and computed tomography (CT) confirmed the existence of a large right atrial mass extending to the superior and inferior vena cava. We initially considered the right atrial mass as a thrombus and performed surgical treatment for the patient. The surgical intervention partially relieved the obstruction of the superior and inferior vena cava and improved hemodynamics. Postoperative pathological examination of the right atrial mass suggested malignant plasmacytoma associated with MM. After recovery from the surgery, the patient received one cycle of chemotherapy. A follow-up of seven months revealed that our patient was still alive with a good general condition.

Conclusions

Increasing the awareness of extramedullary intracardiac lesions in patients with MM is warranted. Our case confirmed that surgical intervention followed by adjuvant chemotherapy could improve the patient’s hemodynamics and achieve remission of cardiac symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant disease of plasma cells commonly associated with bone marrow plasmacytosis. The incidence of extramedullary lesions in MM is approximately 6–20% [1, 2]. However, cardiac involvement associated with MM is a rare manifestation with an incidence of less than 1% [1,2,3]. Thus, the experience in the diagnosis and management of cardiac involvement in MM is limited. Here, we present an MM patient whose large right atrial extramedullary plasmacytoma was initially misdiagnosed as a thrombus.

Case presentation

Clinical history

A 67-year-old male was admitted for exertional dyspnea and fatigue. He was diagnosed with MM one year earlier. He had received chemotherapy with bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone, achieving nearly complete remission without maintenance therapy. Two months earlier, he was diagnosed with sick sinus syndrome due to syncope and was implanted with a permanent pacemaker. After this admission, the patient had a body temperature of 36 °C, blood pressure of 119/72 mmHg, pulse rate of 74 beats per min, and respiratory rate of 20 beats per min. Physical examination revealed mild edema on his face and lower extremity. Slightly distended jugular veins were observed. The electrocardiogram revealed atrial fibrillation. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed a significant and irregularly shaped mass filling the right atrium (RA) (Fig. 1a) and obstructing the right ventricular inflow tract. The mass also extended into the superior vena cava (SVC) and inferior vena cava (IVC), resulting in almost complete occlusion of the SVC and partial obstruction of the IVC (Fig. 1b and c). A computed tomography (CT) scan also demonstrated a large mass in the RA extending to the SVC and IVC (Fig. 1d–f). The large mass surrounded the pacemaker lead (Fig. 1d). Bilateral pleural effusions were also observed. Angiography was negative for pulmonary embolism. The laboratory test showed a white blood cell count of 4.5 × 109/L, hemoglobin level of 127 g/L, platelet count of 119 × 109/L, creatinine level of 108 μmol/L, and alanine aminotransferase level of 57.7 U/L.

Echo view: a The arrows indicate that the large mass occupied most of the RA. b The arrows indicate that the mass extended into the IVC. c The arrow indicates that the mass extended into the SVC. Transverse view of CTA: d, e and f The arrows demonstrate the large mass in the RA extending into the IVC and SVC. The yellow arrow indicates the mass surrounding the pacemaker lead (d). RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; AAO, ascending aorta; SVC, superior vena cava; IVC, inferior vena cava; AoA, aortic arch; CTA, computed tomographic angiography

Treatment

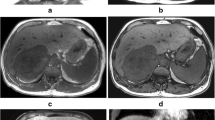

Because the patient was in a stable course of MM and the pacemaker led through his SVC and RA, we initially considered the mass to be a right atrial thrombus. The patient underwent right atrial mass resection under cardiopulmonary bypass. Intraoperative findings revealed multiple lobulated masses occupying most of the RA (Fig. 2a), extending to the SVC and IVC. The mass also infiltrated the free wall of the RA, especially “freezing” the anterolateral wall of the RA. Intraoperative rapid pathological examination of the mass indicated a malignant tumor. The large mass in the RA could not be completely removed due to infiltration of the atrial wall. Therefore, a partial tumor and the anterolateral wall of the RA were resected to relieve the obstruction of the SVC, IVC, and right ventricular inflow tract. Then, the incision of the RA was reconstructed with a pericardial patch. The patient recovered uneventfully after the surgery. One month later, he received one cycle of chemotherapy with bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone.

Pathology and diagnosis

Postoperative pathological examination of the right atrial mass suggested malignant plasmacytoma associated with MM. Immunocytochemical staining of the tumor sections indicated atypical immature plasma cells positive for CD138, CD38, CyclinD1, and λ, and negative for CD20, CD79a, and CD10 (Fig. 2b).

Outcome

After follow-up for seven months, our patient was still alive with a considerably good health condition after surgery. His echocardiography showed no intracardiac relapse of MM.

Discussion and conclusion

Extramedullary cardiac plasmacytoma is extremely rare in patients with MM. Cardiac involvement of MM includes pericardial effusion [4], pericardial mass [5], intracardiac mass [2, 3, 6, 7], and myocardial infiltration [8, 9]. Extramedullary cardiac plasmacytoma may be either the initial or secondary presentation of MM [3]. A previous study suggested that extramedullary involvement of MM is relatively common in patients after receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [4]. However, our patient did not receive hematopoietic stem cell transplantation during MM therapy.

The clinical symptoms of extramedullary intracardiac MM are nonspecific, depending on the localization and size of the mass. Patients might present with pericardial tamponade, arrhythmia, SVC syndrome, or severe heart failure [5, 10]. In this case, the large right atrial mass resulted in symptoms of SVC obstruction and right heart dysfunction in the patient. His previous sinus node dysfunction might also be associated with myocardial infiltration of the intracardiac plasmacytoma.

The diagnosis of extramedullary intracardiac MM requires pathological examination by transvenous biopsy or after surgical resection [7, 11]. Echocardiography and CT are the most commonly utilized imaging modalities to present the size and shape of the intracardiac mass but not to distinguish intracardiac plasmacytoma from other more common masses, such as thrombus, myxoma, or lymphoma. Contrast echocardiography may facilitate the classification of intracardiac tumors and thrombi [12]. Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful for characterizing the involvement of intramedullary and extramedullary lesions associated with MM [1]. In our case, contrast echocardiography was not performed, and cardiac MRI was also not performed due to the in situ pacemaker. We initially misdiagnosed the right atrial mass as a thrombus because of the patient's history of implants in the right heart and his stable course of MM within one year after chemotherapy. This case indicated that extramedullary intracardiac lesions should not be overlooked in patients with MM, even during the stable course.

Extramedullary intracardiac lesions in MM patients carry a poor prognosis. More than half of the patients die within two days to 15 months after diagnosis [4, 11, 13]. The optimal therapy or management for intracardiac plasmacytoma is not yet well defined. Surgical resection, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, alone or in combination, have been reported in a few cases to significantly decrease the size of intracardiac plasmacytoma and control cardiovascular symptoms but not to achieve long-term success [3, 6, 9, 13]. Admittedly, the appraisal and data of therapeutic strategy and outcome are limited due to the rarity of this disease. Surgical intervention is usually palliative because the intracardiac plasmacytoma usually infiltrates the myocardium and cannot be removed entirely. However, surgical intervention could immediately improve hemodynamics [10, 13]. Our patient differed from the previous patients who received surgical intervention for intracardiac plasmacytomas in one crucial aspect. In our case, except for most of the mass in the right atrial cavity, the infiltrated anterolateral wall of the RA was also resected and reconstructed with a pericardial patch. Our surgical strategy relieved the obstruction of the SVC and right ventricular inflow tract to the greatest extent. The surgical intervention followed by adjuvant chemotherapy resulted in a complete resolution of our patient’s symptoms of dyspnea and fatigue.

Extramedullary MM is distinctly uncommon in the heart, but it most often involves the upper respiratory tract, soft tissue, and gastrointestinal tract [9]. The clinical symptoms of extramedullary MM depend on the organs of involvement. Despite recognition of the poor prognosis of extramedullary MM, treatment and outcomes have not been fully studied. The data on chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgical resection, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation are limited [9]. Multimodal therapy may be associated with superior outcomes but needs adequately powered future studies.

In conclusion, increasing the awareness of extramedullary intracardiac lesions in patients with MM is warranted. Our practice confirmed that surgical intervention followed by adjuvant chemotherapy could achieve remission of cardiac symptoms.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- MM:

-

Multiple myeloma

- RA:

-

Right atrium

- TTE:

-

Transthoracic echocardiography

- SVC:

-

Superior vena cava

- IVC:

-

Inferior vena cava

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CTA:

-

Computed tomographic angiography

References

Chen T, Taubman K, Xiao H, Yap K, Schlicht S. Cardiac tamponade in multiple myeloma—a pictorial case review of FDG PET/CT findings. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2020;64:377–8.

Wan X, Tarantolo S, Orton DF, Greiner TC. Primary extramedullary plasmacytoma in atria of the heat. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2001;10:137–9.

Paulus A, Swaika A, Miller CK, Spangenthal JE, Guo R, Vonfricken K, et al. Clinical relapse in a patient with multiple myeloma presenting as an atrial plasmacytoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e47–9.

Coakley M, Yeneneh B, Rosenthal A, Fonseca R, Mookadam F. Extramedullary cardiac multiple myeloma—a case report and contemporary review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016;16:246–52.

Franzese MG, Leva R, Correale M, Palumbo G, Capalbo SF, Biase MD. An extramedullary lesion in multiple myeloma: voluminous pericardial mass. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:E73.

Vigo F, Ciammella P, Valli R, Cagni E, Lotti C. Extraskeletal multiple myeloma presenting with an atrial mass: a case report and a review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:236.

Owens P, Morgan-Hughes G, Kelly S, Ring N, Marshall AJ. Myeloma and a mass in the heart. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:288–9.

Fukae T, Hakuno D. Extramedullary lesions to the pericardium and right atrium in refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2019;1:134–1562.

Guan X, Jalil A, Khanal K, Liu B, Jain AG. Extramedullary plasmacytoma involving the heat: a case report and focused literature review. Cureus. 2020;12:e7418.

Behzadnia N, Sheybani-Afshar F, Hossein-Ahmadi Z, Ansari-Asl Z, Sharif-Kashani B, Dorudinia A. Late relapse of multiple myeloma presenting as a right atrial mass. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2014;22:1106–8.

Fernandez LA, Couban S, Sy R, Miller R. An unusual presentation of extramedullary plasmacytoma occurring sequentially in the tesis, subcutaneous tissue, and heart. Am J Hematol. 2001;67:194–6.

Mulvagh SL, Rakowski H, Vannan MA, Abdelmoneim SS, Becher H, Bierig SM, et al. American society of echocardiography consensus statement on the clinical applications of ultrasonic contrast agents in echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:1179–201.

Keung YK, Lau S, Gill P. Extramedullary plasmacytoma of the heart presenting as cardiac emergency: review of literature. Am J Clin Oncol. 1994;17:427–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated in the management of the patient in this case report. LP drafted the manuscript. RW supervised the writing of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, L., Wang, R. Extramedullary intracardiac multiple myeloma misdiagnosed as a thrombus: a case report. BMC Surg 21, 375 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-021-01377-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-021-01377-y