Abstract

Background

Surgical closure of anal fistulas with rectal advancement flaps is an established standard method, but it has a high degree of healing failure in some cases. The aim of this study was to identify risk factors for anal fistula healing failure after advancement flap placement between patients with cryptoglandular fistulas and patients with Crohn’s disease (CD).

Methods

From January 2010 to October 2020, 155 rectal advancement flaps (CD patients = 55, non-CD patients = 100) were performed. Patients were entered into a prospective database, and healing rates were retrospectively analysed.

Results

The median follow-up period was 189 days (95% CI: 109–269). The overall complication rate was 5.8%. The total healing rate for all rectal advancement flaps was 56%. CD patients were younger (33 vs. 43 years, p < 0.001), more often female (76% vs. 30%, p < 0.001), were administered more immunosuppressant medication (65% vs. 5%, p < 0.001), and had more rectovaginal fistulas (29% vs. 8%, p = 0.001) and more protective stomas (49% vs. 2%, p < 0.001) than patients without CD. However, no difference in healing rate was noted between patients with or without CD (47% vs. 60%, p = 0.088).

Conclusions

Patients with anal fistulas with and without Crohn’s disease exhibit the same healing rate. Although patients with CD display different patient-specific characteristics, no independent factors for the occurrence of anal fistula healing failure could be determined.

Trial registration Not applicable due to the retrospective study design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Treatment of anal fistulas is difficult and is associated with high rates of healing failure, sphincter damage, incontinence, and impaired quality of life. A variety of treatment options exist, including fistulotomy for superficial fistula course or seton drainage [1, 2]. Fistula closure can also be performed using surgical reconstructive and sphincter-preserving methods, such as mucosal or submucosal rectal advancement flap or LIFT (ligation of intersphinteric fistula tract) procedures [3,4,5,6]. The results after LIFT or advancement flap were examined separately in a large review for cryptoglandular and CD fistulas with comparable results [6]. However, no comparison between cryptoglandular and CD fistulas was performed in this study. In addition, biomaterials, such as fibrin, collagen, or even autologous stem cells, have also been developed for fistula closure [7, 8]. Despite the large number of different treatment options, no procedure has achieved a breakthrough in the treatment of anal fistulas, and the healing rates remain unsatisfactory. Wide ranges of healing rates for the above procedures have been reported in the literature. The rectal advancement flap exhibits the best healing rates (between 30 and 100%) [9,10,11]. Previous studies described poor results after flap advancement in patients with active Crohn's disease [12, 13]. Proctitis or stenosis should therefore be resolved before advancement flap procedures are performed. If inflammation is present, systemic or topical therapy should be administered, especially in CD patients.

To date, studies regarding healing rates of anal fistulas in CD patients are rare [14, 15]. Prospective studies date from the 1990s and examine only a small number of CD patients. In addition, only a few studies, some of which have small case numbers, compare the results of an advancement flap for CD-associated anal fistulas and cryptoglandular anal fistulas [13, 16, 17]. A limited number of retrospective studies on CD anal fistulas address various surgical treatments, including seton drainage and fistulotomy, without a focus on advancement flaps [18].

The primary aim of this study was to compare the healing rate after the use of rectal advancement flaps for anal fistulas in patients with cryptoglandular fistulas and patients with Crohn’s disease. The second aim was to identify risk factors for healing failure in CD patients.

Methods

Patients

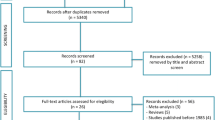

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin (EA4/149/20). From January 2010 to October 2020, 155 rectal advancement flaps were performed consecutively for patients with anal fistula in Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Campus Benjamin Franklin. Data analysis included both CD patients and patients with cryptoglandular fistulas. The inclusion criteria were all patients with rectal advancement flaps for anal fistula. Exclusion criteria were age under 18 years and surgical treatments (seton drainage, fistula cutting, stem cell therapy, and gracilis flap) other than rectal advancement flap. In CD patients, the indication for an advancement flap was a healed perianal abscess and a CD-free rectal mucosa. All rectal advancement flaps were performed by surgeons experienced in proctology and CD in our department. In this technique, the internal fistula opening is closed with a flap including the lamina muscularis and the mucosa of the rectum wall. The external opening of the fistula is excised or debrided. No additional surgery was performed during fistula repair. As planned, our patients came for their first follow-up after four to six weeks. CD patients were consulted more often. No scheduled follow-up was conducted after the healing was complete. Patients were only examined more frequently in cases of failure to heal.

Aim, design, and settings

Data were collected from the hospital's electronic patient record system (EHS) in a prospective database and retrospectively evaluated. The primary aim was fistula healing. It was defined as complete healing of the fistulous tract (clinically and in anal endoscopic ultrasound) without the need for reoperation or replacement of the seton drain. In contrast, healing failure was defined as evidence of a recurrent fistula that required at least seton drainage or reoperation. Healing failure included persisting fistula (early recurrence) and recurrence of new fistula (late recurrence). Lost to follow-up was defined as any lack of contact after patient discharge. For evaluation, patient age, diagnosis, sex, immunosuppressant medication, ASA (American Society of Anaesthesiologists) score, body mass index (BMI), rectovaginal fistula course, protective stoma, and complication rate (Clavien-Dindo classification) were documented. Nicotine and alcohol abuse were not recorded due to the lack of documentation.

Statistics

Given that most variables did not show a normal distribution, nonparametric tests were used for statistical comparison. Continuous variables are displayed as medians (minimum–maximum), and categorical variables are displayed as counts (percentages). The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare two independent groups. Group comparisons for categorical variables were performed using the chi-square test. The level of significance was 0.05 (2-sided) for each statistical test. P-values concerning secondary endpoints were considered exploratory and are presented without Bonferroni correction. Factors with P-values less than 0.2 were enrolled in a Cox hazard regression model to identify independent risk factors. Kaplan–Meier estimates were calculated for the healing rate with the last available contact date (follow-up = time to event). The log rank test was used for the comparison between patients without and with CD. We assumed that loss to follow-up was missing not at random (MNAR) and did not address this with specific statistical measures. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics Software 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patients

Between January 2010 and June 2020, 155 mucosal advancement flap operations for patients with anal fistula were performed (Table 1). The study included 55 CD patients and 100 non-CD patients. Most patients had complex fistulas. In total, 83% had a transsphincteric fistula, and 15% had a rectovaginal fistula course. Immunosuppressant medication was administered to 41 patients (26%). Median healing over all flaps was 56%. Nine patients (5.8%) developed acute complications (haematoma, bleeding) with the need for reperform surgery. Two patients (1%) were lost to follow-up.

Risk of anal fistula healing failure after advancement flap for all patients

In Table 2, univariate analysis showed that female sex, immunosuppressant medication, and rectovaginal fistula course were significant influencing factors for healing failure. Crohn’s disease, BMI, ASA 1 and 2, or the presence of protective stoma showed no influence on anal fistula healing failure. P-values less than 0.2 from the univariate analysis were enrolled in a Cox proportional hazard model to identify independent risk factors for healing failure. Cox regression analysis could not identify any independent influencing factor on healing after rectal advancement flap placement.

Advancement flap in CD patients

Table 3 shows the modified Montreal Classification [19] for all CD patients. Differences in the characteristics of patients with and without CD are presented in Table 4. CD patients were significantly younger, were more often female, received more immunosuppressant medication, and had a lower BMI than non-CD patients. In addition, CD patients were more likely to have a protective ostomy. There were significantly more patients with rectovaginal fistulas among CD patients. However, the healing rate of anal fistula did not differ between CD and non-CD patients (p = 0.088).

A subgroup analysis was performed for CD patients to identify possible influencing factors for anal fistula healing failure (Table 5). Neither age nor sex, sex, BMI, ASA, or immunosuppressant medication showed a significant influence on fistula healing after flap advancement. A rectovaginal fistula course or the presence of a protective stoma was also irrelevant to the healing process. P-values less than 0.2 from the univariate analysis were enrolled in a Cox proportional hazard model to identify independent risk factors for healing failure. Cox regression analysis could not find any independent influencing factor on healing after rectal advancement flap placement.

Healing failure

The median follow-up for CD patients was 210 days (95% CI: 53–368). Non-CD patients had a median follow-up of 89 days (111–267). Two patients (1%) were lost to follow-up. Healing failure occurred in 69 (44%) of 155 advancement flaps. Kaplan–Meier estimates for fistula healing failure did not differ between patients with cryptoglandular fistulas and patients with CD (Fig. 1).

The CD and non-CD patients with anal fistula healing failure were further classified into two categories according to the time of relapse. An early relapse was reported within 14 days and is equivalent to a persisting fistula. A late relapse was reported after 14 days. Of 29 CD patients with anal fistula healing failure, 8 patients (28%) had a median early relapse of 10 days (6–12), and 21 patients (72%) had a median late relapse of 84 days (29–1016). Of 40 non-CD patients with anal fistula healing failure, 14 (35%) patients had a median early relapse of 8 days (4–14), and 26 patients (65%) had a median late relapse of 85 days (16–1521). The difference for both early (p = 0.552) and late (p = 0.082) healing failure was not significant.

Discussion

Patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) are a special and demanding group of patients with a known increase in perioperative morbidity [20, 21]. This also includes the surgical treatment of CD-associated anal fistulas. Given limited evidence on healing rates after advancement flaps in CD [15, 22,23,24], we aimed to analyse potential risk factors for healing failure in this particular group of patients.

We showed that CD patients significantly differed from patients with cryptoglandular fistulas, especially concerning increased immunosuppression and the presence of ostomy. Nevertheless, CD patients did not have an increased risk of healing failure compared with patients with cryptoglandular fistulas. Although CD patients were significantly younger and were more often female, had a smaller BMI and were taking immunosuppressant drugs more frequently, no independent risk factors for healing failure of anal fistula after advancement flap were identified. This is a comparative study on this subject. In the past, most studies dealt with either only CD patients or only cryptoglandular fistulas [4, 22, 25].

Various risk factors for failure of fistula healing have been reported in the literature. Previous work identified obesity as a risk factor for healing failure of anal fistulas [26, 27]. This statement is not consistent with our results. Our results showed that non-CD patients had a significantly higher BMI than CD patients. However, no influence of BMI on anal fistula healing was noted in either CD or non-CD patients. Therefore, it remains unclear whether BMI affects healing after rectal advancement flaps.

Several technical options are available for rectal advancement flaps. Simple mucosal, partial or full-thickness flaps are described in the literature, and analyses concerning their possible healing failure have been reported [28]. The best results are described for full-thickness flaps [30]. The technique used in our patients was most similar to the partial thickness flap with moderate results. We prefer this technique to avoid major tissue defects and injuries to the sphincter.

Another common risk factor for postoperative healing disorders is nicotine abuse, especially in CD patients [29, 30]. Previous data showed that there was no influence of nicotine, even excessive smoking, on anal fistula recurrence [31, 32]. We did not assess this variable in our work. As this is a retrospective data analysis, this value was not fully documented and could therefore not be adequately assessed.

Rectovaginal fistulas are associated with healing disorders after anal fistula repair. Different studies have demonstrated this effect for different surgical therapies, such as internal and external flaps [15, 33]. In the case of persistent, complicating, or recurrent abscessing fistulation, proctectomy is necessary for some patients [34]. Indeed, rectovaginal fistulas occurred more frequently in CD patients in our study. However, our analyses showed that this factor did not affect the healing rate. Therefore, we believe that the inclusion of patients with rectovaginal fistulas is feasible and does not introduce a significant bias. Over the years, particularly difficult and complex rectovaginal fistulas have been treated more often with other surgical techniques, such as gracilis flaps, in our department. This phenomenon could explain the lower healing rates of rectovaginal fistulas after rectal advancement flaps in our study. It should also be mentioned that in addition to the increasing indication for primary gracilis flap in difficult and complex rectovaginal fistulas, at least in the case of a recurrence of a rectovaginal fistula, the gracilis flap should be used for fistula closure [35]. Furthermore, the application of transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) for advancement rectal flaps could improve the healing outcome even in difficult situations (such as high rectal fistulas) [36]. Treatment of anal fistula with gracilis flap or Martius flap was not assessed in this study but is planned for further work.

Proximal bowel diversion was previously reported to be associated with lower recurrence rates after anal fistula surgery. However, studies do not agree on whether and when a positive effect can be achieved depending on the severity of the underlying disease [37, 38]. In our work, CD patients were more likely to have a protective stoma, but this did not affect the healing rate. It can therefore be assumed that other factors, such as the course of the fistula or the severity of Crohn's disease, may play a role in fistula healing.

One limitation of the study is its retrospective nature. In addition, the heterogeneous group of patients, including CD and non-CD patients as well as patients with complex fistulas, seems to represent a further limitation. On one hand, we divided CD and non-CD patients and analysed these patients separately. On the other hand, complex fistulas are typical for CD patients and should therefore be specifically included in the analysis. Including all the patients above, it was possible to conduct a detailed analysis for rectal advancement flaps with a high number of patients achieving important results generally for anal fistula treatment, particularly CD patients. Furthermore, we did not perform a power analysis a priori, so we can only surmise whether the analysis is statistically powered. To the best of our knowledge, this study includes the greatest number of patients in total and CD patients in particular on this subject.

Conclusions

Patients with Crohn’s disease often present with complicated anal fistulas, increased immunosuppression, and ostomy. However, the healing rate after rectal advancement flap placement is similar to that of patients with cryptoglandular fistulas.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CD:

-

Crohn’s disease

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- LIFT:

-

Ligation of intersphinteric fistula tract

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists score

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- MNAR:

-

Missing not at random

References

Patton V, Chen CM, Lubowski D. Long-term results of the cutting seton for high anal fistula. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85(10):720–7.

Seyfried S, Bussen D, Joos A, Galata C, Weiss C, Herold A. Fistulectomy with primary sphincter reconstruction. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33(7):911–8.

Chen H-J, Sun G-D, Zhu P, Zhou Z-L, Chen Y-G, Yang B-L. Effective and long-term outcome following ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) for transsphincteric fistula. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(4):583–5.

Podetta M, Scarpa CR, Zufferey G, Skala K, Ris F, Roche B. Mucosal advancement flap for recurrent complex anal fistula: a repeatable procedure. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34(1):197–200.

van Praag EM, Stellingwerf ME, van der Bilt JDW, Bemelman WA, Gecse KB, Buskens CJ. Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract and endorectal advancement flap for high perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: a retrospective cohort study. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(6):757–63.

Stellingwerf ME, van Praag EM, Tozer PJ, Bemelman WA, Buskens CJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of endorectal advancement flap and ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract for cryptoglandular and Crohn’s high perianal fistulas. BJS Open Juni. 2019;3(3):231–41.

Cadeddu F, Salis F, Lisi G, Ciangola I, Milito G. Complex anal fistula remains a challenge for colorectal surgeon. Int J Colorectal Dis Mai. 2015;30(5):595–603.

Zhou C, Li M, Zhang Y, Ni M, Wang Y, Xu D. Autologous adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of Crohn’s fistula-in-ano: an open-label, controlled trial. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):124.

Christoforidis D, Pieh MC, Madoff RD, Mellgren AF. Treatment of transsphincteric anal fistulas by endorectal advancement flap or collagen fistula plug: a comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum Januar. 2009;52(1):18–22.

Koehler A, Risse-Schaaf A, Athanasiadis S. Treatment for horseshoe fistulas-in-ano with primary closure of the internal fistula opening: a clinical and manometric study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(11):1874–82.

Ortiz H, Marzo J, Ciga MA, Oteiza F, Armendáriz P, de Miguel M. Randomized clinical trial of anal fistula plug versus endorectal advancement flap for the treatment of high cryptoglandular fistula in ano. Br J Surg Juni. 2009;96(6):608–12.

Lewis RT, Bleier JIS. Surgical treatment of anorectal crohn disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg Juni. 2013;26(2):90–9.

Mizrahi N, Wexner SD, Zmora O, Da Silva G, Efron J, Weiss EG. Endorectal advancement flap: are there predictors of failure? Dis Colon Rectum Dezember. 2002;45(12):1616–21.

Hyman N. Endoanal advancement flap repair for complex anorectal fistulas. Am J Surg Oktober. 1999;178(4):337–40.

Makowiec F, Jehle EC, Becker HD, Starlinger M. Clinical course after transanal advancement flap repair of perianal fistula in patients with Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg Mai. 1995;82(5):603–6.

Bessi G, Siproudhis L, Merlini l’Héritier A, Wallenhorst T, le Balc’h E, Bouguen G. Advancement flap procedure in Crohn and non-Crohn perineal fistulas: a simple surgical approach. Colorectal Dis Off J Assoc Coloproctology. 2019;21(1):66–72.

Jarrar A, Church J. Advancement flap repair: a good option for complex anorectal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum Dezember. 2011;54(12):1537–41.

van Koperen PJ, Safiruddin F, Bemelman WA, Slors JFM. Outcome of surgical treatment for fistula in ano in Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg Juni. 2009;96(6):675–9.

Stallmach A, Bokemeyer B, Helwig U, Luegering A, Teich N, Fischer I. Predictive parameters for the clinical course of Crohn’s disease: development of a simple and reliable risk model. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34:1.

Eisner F, Küper MA, Ziegler F, Zieker D, Königsrainer A, Glatzle J. Impact of perioperative immunosuppressive medication on surgical outcome in Crohn’s Disease (CD). Z Für Gastroenterol Mai. 2014;52(5):436–40.

Longo WE, Oakley JR, Lavery IC, Church JM, Fazio VW. Outcome of ileorectal anastomosis for Crohn’s colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35(11):1066–71.

DeLeon MF, Hull TL. Treatment Strategies in Crohn’s-Associated Rectovaginal Fistula. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32(4):261–7.

Lee MJ, Heywood N, Adegbola S, Tozer P, Sahnan K, Fearnhead NS. Systematic review of surgical interventions for Crohn’s anal fistula. BJS Open. 2017;1(3):55–66.

Mei Z, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Liu P, Ge M, Du P. Risk factors for recurrence after anal fistula surgery: a meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2019;69:153–64.

Mujukian A, Truong A, Fleshner P, Zaghiyan K. Long-term healing after complex anal fistula repair in patients with Crohn’s disease. Tech Coloproctol. 2020;24(8):833–41.

Boenicke L, Karsten E, Zirngibl H, Ambe P. Advancement flap for treatment of complex cryptoglandular anal fistula: prediction of therapy success or failure using anamnestic and clinical parameters. World J Surg. 2017;41(9):2395–400.

Schwandner O. Obesity is a negative predictor of success after surgery for complex anal fistula. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:61.

Balciscueta Z, Uribe N, Balciscueta I, Andreu-Ballester JC, García-Granero E. Rectal advancement flap for the treatment of complex cryptoglandular anal fistulas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis Mai. 2017;32(5):599–609.

Aniwan S, Park SH, Loftus EV. Epidemiology, natural history, and risk stratification of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2017;46(3):463–80.

Moser MA, Okun NB, Mayes DC, Bailey RJ. Crohn’s disease, pregnancy, and birth weight. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(4):1021–6.

van Koperen PJ, Wind J, Bemelman WA, Bakx R, Reitsma JB, Slors JFM. Long-term functional outcome and risk factors for recurrence after surgical treatment for low and high perianal fistulas of cryptoglandular origin. Dis Colon Rectum Oktober. 2008;51(10):1475–81.

van Onkelen RS, Gosselink MP, Thijsse S, Schouten WR. Predictors of outcome after transanal advancement flap repair for high transsphincteric fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(8):1007–11.

Hannaway CD, Hull TL. Current considerations in the management of rectovaginal fistula from Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis Off J Assoc Coloproctology 2008;10(8):747–55. (discussion 755–756).

Park SH, Aniwan S, Scott Harmsen W, Tremaine WJ, Lightner AL, Faubion WA. Update on the natural course of fistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease in a population-based cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(6):1054–60.

Rottoli M, Vallicelli C, Boschi L, Cipriani R, Poggioli G. Gracilis muscle transposition for the treatment of recurrent rectovaginal and pouch-vaginal fistula: is Crohn’s disease a risk factor for failure? A prospective cohort study. Updat Surg Dezember. 2018;70(4):485–90.

Rottoli M, di Simone MP, Poggioli G. TAMIS-flap technique: full-thickness advancement rectal flap for high perianal fistulae performed through transanal minimally invasive surgery. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2019;29(4):e53.

Burke JP. Role of fecal diversion in complex Crohn’s disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg Juli. 2019;32(4):273–9.

Bafford AC, Latushko A, Hansraj N, Jambaulikar G, Ghazi LJ. The use of temporary fecal diversion in colonic and perianal Crohn’s disease does not improve outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(8):2079–86.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study has not received any third-party funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The idea and initial findings were made by IP, CS, and CH. Data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation were done by CS and KSL with input from all authors. During writing this manuscript by CS and KSL, IP and CH were involved in constant discussions and improvements of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin (EA4/149/20). Since this is a retrospective study, a written declaration of consent from the patient based on the legal basis of section 25 of the State Hospital Law (LKG Berlin) is not required. This was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin (EA4/149/20). This study was performed following the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Seifarth, C., Lehmann, K.S., Holmer, C. et al. Healing of rectal advancement flaps for anal fistulas in patients with and without Crohn’s disease: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMC Surg 21, 283 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-021-01282-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-021-01282-4