Abstract

Background

The common complications of radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy usually include wound infection, hemorrhage or hematomas, lymphocele, uretheral injury, ileus and incisional hernias. However, internal hernia secondary to the orifice associated with the uncovered vessels after pelvic lymphadenectomy is very rare.

Case presentation

We report a case of internal hernia with intestinal perforation beneath the superior vesical artery that occurred one month after laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer. A partial ileum resection was performed and the right superior vesical artery was transected to prevent recurrence of the internal hernia.

Conclusions

Retroperitonealization after the pelvic lymphadenectomy should be considered in patients with tortuous, elongated arteries which could be causal lesions of an internal hernia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy is a standard procedure in the radical surgery for cervical cancer. The common complications of radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy usually include wound infection, hemorrhage or hematomas, lymphocele, uretheral injury, ileus and incisional hernias [1]. However, internal hernia secondary to the orifice associated with the skeletonized vessels is very rare. Here we first report a case of internal hernia beneath superior vesical artery after pelvic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer and conduct a literature review.

Case presentation

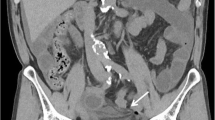

A 53-year-old woman underwent a laparoscopic radical hysterectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, para-aortic lymph node dissection and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for cervical cancer. In addition, a double J tube was placed in the left ureter for the sake of intraoperative urethral injury. The surgical pathology showed moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma and tumour metastasis was not found in the dissected 71 lymph nodes (Stage IB3). The postoperative hospital stay was uneventful and the patient was discharged 15 days after surgery. Two weeks later, she was admitted to our hospital again with a 5-day history of abdominal pain, vomiting, and the inability to pass gas or stools. Physical examination showed the abdominal distension, tenderness and hyperactive bowel sounds without rebound tenderness and muscular defense. Generally, the laboratory findings were not remarkable. CT scan revealed small bowel obstruction (Fig. 1a).

a CT scan revealed small intestine gas–liquid plane. b Small bowel obstruction. c White arrow for free gas in the abdominal cavity. d EIA external iliac artery. EIV external iliac vein. IIA internal iliac artery. U ureter. SVA superior vesical artery, black arrow for hernia ring defect. e White arrow shows the outflow of digestive juice

Based on these data, the patient was tentatively diagnosed as adhesive small bowel obstruction and then she received comprehensive conservative treatment. However, no significant improvement was observed in the ileus condition. On the sixth day, her abdominal pain suddenly aggravated with mild fever (37.3℃) and physical examination showed severe abdominal tenderness with rebound tenderness, especially in the hypogastric region. Laboratory data showed the elevation of white blood cell count (10.75 × 109 /L, 3.5–9.5 × 109 /L) and neutrophil granulocyte percentage (0.912, 0.40–0.75). CT scan revealed the ileus with a caliber change of the small bowel in the right lateral pelvic cavity and free gas in the abdominal cavity which suggested perforation of intestine (Fig. 1b, c). In view of the patient's acute abdominal condition, an emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed.

To avoid the possible adhesion of umbilicus from the previous operation and extend incision easily, we made a 12 cm incision through the rectus abdominis and found there were about 200 ml pus and digestive juices in the abdominal cavity. Intraoperative exploration revealed severe intestinal dilation and the incarcerated internal herniation of the distal ileum (20 cm length, 40 cm from Bauhin’s valve) through an orifice formed by the uncovered right superior vesical artery and the right lateral pelvic wall (Fig. 1d). After reduction of the herniated intestine, the incarcerated small bowel recovered good vitality. However, a 0.8 cm size perforation was found in the contralateral mesenteric region of the ileum about 80 cm far from Bauhin’s valve with leakage of digestive fluid (Fig. 1e). In addition, the intestinal wall surrounding the perforation was highly congested and a partial ileum resection was performed. Then the right superior vesical artery was transected to prevent recurrence of the internal hernia. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged from hospital on the tenth day after operation.

Discussion and conclusions

Radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy is the recommended surgical option for stage IB1, IB2 and partial IB3 cervical cancer according to the NCCN guidelines [2]. Laparoscopic surgery has gradually been accepted as a safe and feasible procedure for cervical cancer in recent years. The intestinal obstruction, most of the cases due to adhesion, accounting for up to 75% of postoperative complications, meanwhile, 0.5–5.0% for internal hernia [3]. Moreover, internal hernia secondary to the orifice associated with the uncovered vessels after lymphadenectomy is very rare.

To the best of our knowledge, Guba et al. first reported an iatrogenic internal hernia beneath the right iliac artery after lymphadenectomy in testicular cancer in 1978 and up to till now, only eight cases were reported in English literatures. The previous reports are shown in Table 1 [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Except for one laparotomy [4], the remaining 7 documents (8 cases) were all laparoscopic or robotic surgery. Hiki et al. reported the adhesion after laparoscopic or robotic surgery was obviously better than that of open surgery [12]. According to the Japanese literature, 200 (laparotomy) versus 276 (laparoscopy) cases of lateral lymph node dissection, there are only 2 cases of internal hernia occurred and all of them are in the laparoscopy group [11]. Minami [10] conjectures the incidence of strangulated bowel obstruction may rise with the increasing number of laparoscopic or robot-assisted pelvic lymphadenectomies, although they have less postoperative adhesion formation than open surgery. However, due to lack of bulk data support, it is worthy of discussion whether internal hernia may increase in future on account of more and more laparoscopic lymphadenectomy surgeries.

The standard radical lymphadenectomy procedure for pelvic cancer usually includes the skeletonization of the pelvic nerves and iliac vessels from neighboring tissues which potentially create an iatrogenic hernia defect. Currently, retroperitonization after lymphadenectomy is rarely performed by gynecologists or urologists. Franchi reported there are no differences in postoperative complications between closure and no closure of the peritoneum [13]. Kadanali believed that unreconstructed peritoneum can reduce the incidence of adhesion [14]. At present, there has been no exact conclusion whether it is more beneficial to retroperitonize after pelvic lymphadenectomy. Measures dealing with hernia defects include omentum coverage, free peritoneum transplantation, partial vascular excision, mesh repair etc. and free peritoneum transplantation is most widely used due to its universality and accessibility [4, 5, 8]. In our case, the right superior vesical artery was transected.

When one patient presents with abdominal pain and intestinal obstruction after pelvic lymphadenectomy, it is important to distinguish the internal hernia from adhesive ileus, because the former is more life-threatening and mostly needs emergency surgery while the latter doesn’t. Although clinical symptoms can not effectively differentiate the two conditions because they are nonspecific, computed tomography (CT) is usually useful for this situation. The characteristic CT finding is the caliber change of the small bowel in the lateral pelvic cavity or the caudal dorsal side of pelvic vessels or nerves [11].

In summary, surgeons should be aware of the increased possibility of internal hernia in patients undergoing laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy. Pelvic retroperitonealization after pelvic lymphadenectomy should be reconsidered for the prevention of internal hernia, especially for laparoscopic or robotic surgery.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EIA:

-

External iliac artery

- EIV:

-

External iliac vein

- IIA:

-

Internal iliac artery

- U:

-

Ureter

- SVA:

-

Superior vesical artery

References

Briganti A, Chun FKH, Salonia A, Suardi N, Gallina A, Da Pozzo LF, et al. Complications and other surgical outcomes associated with extended pelvic lymphadenectomy in men with localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2006;50(5):1006–13.

Koh WJ, Abu-Rustum NR, Bean S, Bradly K, Campos SM, Cho KR, et al. Cervical cancer, version 32019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(1):64–84.

Martin LC, Merkle EM, Thompson WM. Review of internal hernias: radiographic and clinical findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(3):703–17.

Guba AM Jr, Lough F, Collins GJ, Feaster M, Rich NM. Iatrogenic internal hernia involving the iliac artery. Ann Surg. 1978;188(1):49–52.

Kim KM, Kim CH, Cho MK, Jeong YY, Kim YH, Choi HS, et al. A strangulated internal hernia behind the external iliac artery after a laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18(4):417–9.

Dumont KA, Wexels JC. Laparoscopic management of a strangulated internal hernia underneath the left external iliac artery. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(11):1041–3.

Ardelt M, Dittmar Y, Scheuerlein H, Bärthel E, Settmacher U. Post-operative internal hernia through an orifice underneath the right common iliac artery after Dargent’s operation. Hernia. 2014;18(6):907–9.

Pridjian A, Myrick S, Zeltser I. Strangulated internal hernia behind the common iliac artery following pelvic lymph node dissection. Urology. 2015;86(5):e23–4.

Viktorin-Baier P, Randazzo M, Medugno C, John H. Internal hernia underneath an elongated external iliac artery: a complication after extended pelvic lymphadenectomy and robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. Urol Case Rep. 2016;8:9–11.

Minami H, Nagasaki T, Akiyoshi T, Konishi T, Fujimoto Y, Nagayama S, Fukanaga Y, et al. Laparoscopic repair of bowel herniation into the space between the obturator nerve and the umbilical artery after pelvic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2018;11(4):409–12.

Kitaguchi D, Nishizawa Y, Sasaki T, Tsukada Y, Kondo A, Hasegawa H, et al. A rare complication after laparoscopic lateral lymph node dissection for rectal cancer: two case reports of internal hernia below the superior vesical artery. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2018;2(3):110–4.

Hiki N, Shimizu N, Yamaguchi H, Imamura K, Kami K, Kubota K, Kiminishi M, et al. Manipulation of the small intestine as a cause of the increased inflammatory response after open compared with laparoscopic surgery. Br J Surg. 2006;93(2):195–204.

Franchi M, Ghezzi F, Zanaboni F, Scarabelli C, Beretta P, Donadello N. Nonclosure of peritoneum at radical abdominal hysterectomy and pelvic node dissection: a randomized study. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(4 Pt 1):622–7.

Kadanali S, Erten O, Kücüközkan T. Pelvic and periaortic pertioneal closure or non-closure at lymphadenectomy in ovarian cancer: effects on morbidity and adhesion formation. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1996;22(3):282–5.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WA was the attending doctors of the patient and wrote this paper. FL helped collect the patient’s clinical information. ZHL searched the relevant articles. HHY provided the therapeutic schedule and revised the paper. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Shandong First Medical University.

Consent for publication

The written consent to publish the personal and clinical details of the participant was obtained and copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ai, W., Liang, Z., Li, F. et al. Internal hernia beneath superior vesical artery after pelvic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer: a case report and literature review. BMC Surg 20, 312 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00985-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00985-4