Abstract

Background

Moving Well is a behavioral intervention for patients with knee osteoarthritis (KOA) scheduled for a total knee replacement (TKR). The objective of this intervention is to help patients with KOA mentally and physically prepare for and recover from TKR.

Methods

This is an open-label pilot randomized clinical trial that will test the feasibility and effectiveness of the Moving Well intervention compared to an attention control group, Staying Well, to reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with KOA undergoing TKR. The Moving Well intervention is guided by Social Cognitive Theory. During this 12-week intervention, participants will receive 7 weekly calls before surgery and 5 weekly calls after surgery from a peer coach. During these calls, participants will be coached to use principles of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), stress reduction techniques, and will be assigned an online exercise program, and self-monitoring activities to complete on their own time throughout the program. Staying Well participants will receive weekly calls of similar duration from research staff to discuss a variety of health topics unrelated to TKR, CBT, or exercise. The primary outcome is the difference in levels of anxiety and/or depression between participants in the Moving Well and Staying Well groups 6 months after TKR.

Discussion

This study will pilot test the feasibility and effectiveness of Moving Well, a peer coach intervention, alongside principles of CBT and home exercise, to help patients with KOA mentally and physically prepare for and recover from TKR.

Trial registration

Clinicaltrials.gov. NCT05217420; Registered: January 31, 2022.

Similar content being viewed by others

Contributions to the literature

-

This clinical trial will pioneer the use of peer coaches for TKR. Peer coaches will have a similar medical profile (age group, history of KOA and TKR) to patients

-

This clinical trial will be the first home-based, telephone delivered pre- and post-operative program. The use of the internet and telephone simplifies the logistics of intervention delivery, facilitating wide scalability of the program.

-

This clinical trial addresses patient pain catastrophizing, depression, and anxiety through CBT for the first time in a pre- and post-operative program for patients with knee OA undergoing TKR.

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common condition affecting an estimated 31 million mostly older US adults between 2008 and 2011 [1]. Knee OA (KOA) can be profoundly debilitating, negatively impacting mobility. Total knee replacement (TKR) is an effective strategy to improve knee function and quality of life, however, up to 30% of patients with TKR continue to experience knee pain after surgery [2,3,4]. Poor prognostic indicators include obesity, pre-operative deconditioning, high levels of anxiety and/or depression, and pain “catastrophizing” (overemphasis on negative aspects or consequences of an experience) before TKR [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Yet few interventions have focused on optimizing both mental and physical health in patients with KOA before and after TKR, especially in patients with these risk factors

One approach is to add pre-habilitation (pre-hab) to post-TKR rehabilitation. A meta-analysis of post-TKR interventions did not show differences in self-reported pain > 12 months after TKR, except for one telephone-delivered, home-based intervention of functional exercises delivered by physical therapists, aimed at managing anxiety related to knee pain [22, 23]. This suggests that post-operative interventions alone may be insufficient. However, studies with pre-hab interventions for joint replacement surgery suffer from methodological shortcomings [24, 25]. In a study by Wang et al. on total hip arthroplasty patients [26], the pre-hab intervention group also received an intensive post-operative exercise program, making it difficult to attribute benefits to the pre-hab intervention alone. A consistent challenge in pre-hab programs was low adherence, potentially because they required in-person interaction with the physical therapist [24, 25]. Hence, having a well-designed, feasible intervention, with pre-hab and rehabilitation components that addresses mental and physical health, can serve as a viable alternative to improve post-TKR pain among patients with KOA.

Several studies have shown strong associations between high levels of anxiety, depression, and negative surgery expectations with worse TKR outcomes [5, 16, 20, 21]. These associations were independent of other factors related to persistent pain and low physical function after TKR. Patients with high pain catastrophizing pre-operatively had 2.67 (95% CI, 1.2–6.1) higher odds of < 50% post-operative improvement in pain after adjustment for potential confounders [16]. This evidence emphasizes that in addition to physical health, mental health has a strong influence on TKR outcomes, yet few interventions have targeted these factors.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a type of psychotherapy that teaches patients how to modify dysfunctional thinking and behavior to solve active problems [27, 28]. CBT has been shown to significantly reduce pain, anxiety, depression, and insomnia among patients suffering from headaches, osteoarthritis pain, depression, and insomnia [29,30,31]. CBT has so far been mainly studied as a way to treat symptoms of OA, and not as a strategy to help patients prepare and recover from TKR [32, 33]. One study that examined pre-TKR CBT for reducing pain catastrophizing and improving pain outcomes after total knee replacement, found no improvement in 3-month pain outcomes after surgery in the intervention group when compared to a non-CBT control [34], indicating that CBT interventions alone may not be sufficient in improving outcomes after TKR.

Peer coaches, also called community health workers, are lay individuals with a specific diagnosis that work with a patient population with the same condition to improve disease management. Peer coaching interventions leverage the interpersonal connection and support between peer and patient to increase patient confidence in achieving favorable outcomes [35]. Studies utilizing peer coaches have demonstrated increased medication adherence among patients with human immunodeficiency virus, asthma, diabetes, and increased cancer screening [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,45]. The social and emotional support peer coaches provide to patients living with the same condition can lead to positive behavior change and engagement and participation in medical decisions related to their condition.

Moving Well is a peer-coach delivered intervention that will incorporate pre-habilitation and principles of CBT, with the standard of care for patients undergoing TKR, in order to pilot test the hypothesis that levels of anxiety and depression will be lower in participants in the intervention group, compared to baseline and the attention control group, Staying Well, at 6, 12, and 24 months post-TKR. A secondary hypothesis is that participants in the Moving Well intervention group will have less knee pain at 6, 12, and 24 months post-TKR compared to the Staying Well attention control group.

Methods

Theoretical framework and implementation framework

The Moving Well peer coach intervention is guided by Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [35]. This theory posits three mechanisms of human agency: direct personal agency (self-efficacy), proxy agency (reliance on others, such as parents or partners, acting at one’s behest to secure desired outcomes), and collective agency (coordinated interdependent efforts). Table 1 shows how the intervention maps to SCT by listing barriers people with KOA face in the effective participation of their own care and matches these barriers to their related theoretical constructs of SCT. It also maps each Moving Well session activity to each construct of the theory. We will use the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework for the implementation and evaluation of the Moving Well intervention [46].

Study population and sample size

The participants of the study will be people with KOA who are 50 years of age or older, have a TKR scheduled in 8 weeks or more, speak English, have access to a computer, the internet, and a working phone. We will exclude people who are unable to exercise (wheelchair-bound or bedbound), have a history of any joint replacement surgery, or have any rheumatic disease other than KOA.

The peer coaches of Moving Well will be people with KOA who had a TKR at least 12 months before they initiate their training as peer coaches of the intervention. This study will have 5 peer coaches.

The sample size estimation assumed four repeated measures, a range of intra-class correlations (0.05 to 0.20) for the repeated measures, and a Bonferroni-adjusted overall type I error of 5% (after controlling for two primary outcomes). We estimate a 20% attrition rate and will recruit 93 subjects, resulting in 37 participants in each arm of the study (total of N = 74 completers). The trial is designed to have at least 80% power to detect a standardized effect size of d = 0.5 or 0.5 standard deviations between the intervention and attention control arms. The standardized effect size is equivalent to a 2.7-point change in the PHQ-8 score, and a 1.6-point change in the GAD-7 score.

Trial design

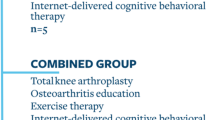

This is an open-label, parallel group, randomized trial that will test the feasibility and effectiveness of a peer coach intervention in lowering the levels of anxiety and/or depression in patients with KOA before and after TKR. All participants will receive the standard of care for patients at the Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) undergoing TKR, which consists of an educational book and a pre-surgery class. Patients with KOA enrolled in the study will be allocated to either the peer coach intervention (Moving Well) group or the attention control (Staying Well) group through a block randomization scheme. Participants will receive 50 dollars for every data collection timepoint.

This protocol is written in accordance with guidelines from the CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) (see Fig. 1 for CONSORT) [47], and the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials [48]. The institutional review board from HSS approved this study (protocol number 2019–1298).

Study interventions

Overview of the Moving Well intervention

Moving Well consists of three main components (Fig. 2): an exercise program delivered through online videos, positive thinking (principle of CBT) training, and peer support with education on TKR, provided through weekly phone sessions between a peer coach and a participant for 12 sessions, 7 sessions in the 7 weeks pre-TKR, and 5 sessions for 5 weeks post-TKR. Table 2 details the curriculum of Moving Well. Each session of the intervention is scripted in the peer coach manual with all the content that the peer coach is responsible to deliver during each of the calls. The participant will have an Activity Book, which will contain the same content as the peer coach manual but with tables, and space to complete the daily activities that are assigned to them by the peer coach.

Moving Well: education materials-Patient Activated Learning System (PALS)

The TKR educational materials for the Moving Well group are available on the Patient Activated Learning System (PALS) website (www.palsforhealth.com) and are listed in Table 2. The PALS is a publicly available educational and empowerment resource informed by SCT designed to provide engaging, easily understood, and well-researched facts for people who want to know more about health, medicine, and diseases [49]. The content in the PALS is evidence-based and peer-reviewed. This content is translated into patient-facing text in plain language, aiming for a seventh-grade reading level. Some content is accompanied by visuals or short videos and a “sticky soundbite” to reinforce the single learning objective for each module, known in the PALS parlance as a renewable knowledge object (RKO). Each RKO includes an assessment question about the information that the reader has just reviewed.

Moving Well: exercise program

The pre-and post-surgery exercise program was designed by a certified physical therapist (KWH), who has extensive experience in TKR rehabilitation. The exercise program will be delivered to participants through online videos recorded by certified doctors in physical therapy from Weill Cornell Medicine (WCM). The videos use people with KOA to demonstrate the exercises. The program focuses on strengthening hip, core, and thigh muscles as well as increasing the knee range of motion. The exercise program allows the participant to select an individualized goal (advanced exercises vs. elementary exercises) based on their self-perceived ability.

Moving Well: principles of cognitive behavioral therapy and positive thinking

During each telephone session, the participants will learn and practice positive thinking, which consists of 3 main steps: Identify negative thinking; Replace negative thinking with positive thinking; Practice positive thoughts and/or healthy behaviors (e.g., exercise, mindfulness) [27, 28]. Each participant is required to monitor their daily mood and negative thoughts, then replace those thoughts with positive thoughts and/or practice positive action. This monitoring process will create self-awareness of their anxiety or depressive symptoms so that they can engage in healthier behaviors. Participants will be instructed on how to perform stress-reduction breathing exercises, meditation, and guided imagery to help manage anxiety and/or depressive symptoms. The CBT component of Moving Well will be a facilitator for each participant to decrease their fear of exercising while experiencing pain so that they can increase their self-efficacy in participating in the required, and often challenging, rehabilitation process after TKR.

Moving Well: peer coach

Peer coaches are not health professionals, they are individuals who have KOA and a history of TKR. Peer coaches will serve as role models and increase participants’ self-efficacy, which is one of the main tenets of the SCT. The role of the peer coach will be to provide support and coaching to each participant so that they successfully complete the activities and assignments of the intervention. The coaching and support by a person who already experienced the same event (had a TKR) will increase the likelihood of behavior change [30, 43, 50, 51]. They will also ensure that participants complete the daily monitoring activities. This will serve to guarantee that participants are completing the activities of the intervention as intended.

The inclusion criteria for peer coaches will be, having KOA and history of TKR at least 12 months before enrollment, and being 60 years of age or older. Once a person who has had TKR meets the criteria to be a peer coach, they will be interviewed by the research team to assess their communication skills. The research team will review each candidate and will document the reasons for not including a candidate as a peer coach. Peer coaches will be considered research subjects and will be consented before starting peer coach training.

Peer coach training

Peer coach training is modeled on a previously published approach [52]. Peer coaches will be scheduled for virtual training meetings. There will be a total of 15 web conference training sessions over 6 months, for up to 6 h a week. Peer coaches will be compensated on an hourly basis for the training and all subsequent interactions with the participants in the peer coach intervention group. Table 2 has details of the Moving Well curriculum, which is the curriculum that peer coaches will be trained on during the 6-month virtual training.

Before each training session, peer coaches-in-training will need to review the learning materials on PALS, listen to recordings of mock sessions between a peer coach and a participant, review the Moving Well participant Activity Book, and review the relevant session in the Peer Coach Manual. During training meetings, peer coaches will receive brief didactic education on the content of the Moving Wellsession assigned for the day, listen to mock sessions, practice delivering the session with a partner, and discuss their performance with the research team and other peer coaches [53]. Every week, peer coaches in training will be paired to practice delivering the session covered in the latest conference on their own time, in preparation for certification of that session. During the certification session, a coach-in-training will deliver the assigned session to a member of the research team over the phone, who will play the role of the participant. The research team will use a checklist to assess proficiency and communication skills during the call (Supplementary File 1). Peer coaches will be approved as peer coaches by members of the research team once they receive scores of 90% or more in all sessions, and each coach will have an opportunity to re-take the certification session if they do not achieve the required score. All peer coaches must pass all certification sessions to be able to work with a participant of Moving Well.

Peer coach training will also include two Motivational Interviewing (MoI) skills training meetings with the research team and only two coaches at a time. Each MoI training meeting will include the following activities: 1) Practicing MoI skills using role-playing scripts where coaches will alternate their roles between coach and participant under the supervision of the research team. 2) Reinforcing skills with live feedback and encouragement, allowing peer coaches to critique each other’s skills and propose ways for improvement on techniques like “rolling with resistance”, “action planning”, and the use of the MoI-style open-ended questions, affirmations, reflective listening, and summaries (OARS).

Peer coach retention

The strategies that we will use to retain coaches include ensuring timely payment for work and continuing education/training with opportunities for practicing skills. Ongoing support will be provided through weekly group conference calls outside of training time. These conference calls are used to problem-solve any challenges encountered, make sure they receive the support that they need to excel as peer coaches, and help build group identity within the peer coaches.

Staying Well: attention control arm

The subjects in the Staying Well attention control group will receive 12 weekly calls (7 before and 5 after TKR) from research assistants. These calls will be similar in length to those of Moving Well and cover topics not related to those of Moving Well or TKR (Table 3). These attention calls will help determine if providing a patient with attention and information not directly related to TKR and rehabilitation will yield the same outcomes as providing specific information and guidance for TKR.

Guidelines for surgery cancellation, postponement, and concomitant care

Participants in both arms of the study will be free to withdraw at any time. In the event of total knee replacement surgery postponement, the participant will be allowed a maximum 2-week interruption in the study schedule. If there is a more than 2-week delay in surgery and therefore a greater than 2-week gap in the study schedule, or the surgery is cancelled, the reason/s for postponement or cancellation will be collected, and the participant will undergo an exit interview, and no further data will be collected. Participants who have taken part in an exit interview will be allowed to rejoin the study later if they wish to, and continue in their previous intervention allocation, however, they must start from the beginning of the intervention schedule. Participants in either arm of the study are permitted to receive any concomitant care related to their knee OA or TKR while in the study.

Participant recruitment, enrollment, and randomization

Participants will be recruited from the orthopedic clinics at HSS in Manhattan, New York. The target sample will be 74 patients. To enroll 74 participants, we expect to screen 500 individuals with KOA who are scheduled to undergo TKR. We will monitor recruitment success including screen failure rates, to inform the design of the planned larger study to follow this one. Patients who meet the inclusion criteria will be contacted by research staff and invited to join the study. Once a patient meets the criteria and we have obtained informed consent, they will be scheduled for their first data collection visit, either in person or virtually, with a blinded research assistant, and subsequently randomized. Block randomization will be used in REDCap to randomize participants to either the Moving Well arm or the Staying Well arm.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome will be the difference in levels of anxiety and depression 6-, 12-, and 24-months post-surgery between Moving Well and Staying Well. The GAD-7 [54] and PHQ-8 [55] will be used to assess the participants’ level of anxiety and depression respectively. Participants will complete the data collection survey at baseline, 6-, 12-, and 24-months post-surgery. If participants have not completed the data collection surveys, a blinded member of the research team will follow up with a phone call to complete the forms over the phone and minimize missing data.

Secondary outcomes will include change from baseline to 6-, 12-, and 24-months post-surgery in the level of social support, general health status, level of pain catastrophizing, knee pain and function, level of self-efficacy, level of sleep disturbance, and opioid use for knee pain. Table 4 has details of the instruments that we will be using to measure primary and secondary outcomes and the time points that data collection will occur. These secondary outcomes will be measured respectively using the following: Lubben Social Network Scale-18 (LSNS-18) [56], 12-Item Short Form Survey (SF-12) [57], Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) [58], Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) Pain and Activities of Daily Living (ADL) sub-scales [59], General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSF) [60], Patient-Reported Outcomes Information System (PROMIS) Sleep Disturbance Scale [61], and participant self-report use of opioids for knee pain.

Other secondary outcomes include the post-surgery inpatient rehabilitation duration assessed by participant self-report at 6 months post-surgery, and change in the following objectively measured physical parameters from baseline to 6 months post-surgery: knee range of motion using a goniometer, Timed Up and Go test (TUG), 6 Minute Walk Test (6MWT), 30-Second Chair Stand test, and quadriceps strength using a handheld dynamometer (only for those that did the data collection in person) [62,63,64]. Table 5 contains information about the measures that will be collected in the study with the corresponding time points.

Implementation and program evaluation

We will use the RE-AIM implementation and program evaluation framework for this study. We will track the number of participants that complete the study in the peer coach intervention arm and control arm. The feasibility of the study will be assessed by examining the completion of the program (80% of enrolled participants complete the intervention), and satisfaction among participants and peer coaches. We will perform one-sample tests on program adherence and high satisfaction in the Moving Well arm by comparing these outcomes with an 80% benchmark.

Demographics of eligible individuals who chose not to participate will be compared to those who did choose to participate to estimate the magnitude of selection bias and to gain an understanding of how the intervention is reaching a diverse group of people with KOA scheduled for TKR. Other feasibility outcomes include the completion rate of the intervention, duration of the phone calls between coaches and clients, sustainability of peer coaches’ network, and retention of peer coaches.

We will invite participants that completed the study and those that drop out to participate in semi-structured interviews regarding their experience with the study. This information will allow us to adapt the intervention for use in in a larger clinical trial. All calls between peer coaches and clients will be recorded and reviewed by the research team to assess the fidelity of the intervention. Peer coaches must have discussed at least 80% of the items in the checklist of each of the sessions to make sure that the intervention is been delivered as intended. We will do additional training for peer coaches that are completing less than 80% of the corresponding session checklist. Table 5 details the implementation and evaluation procedures of the intervention.

Data analysis

We will use descriptive statistics, t-tests, and Chi-square tests as appropriate to compare patients in each study arm. We will assess group differences between baseline and the week before TKR, 6 weeks after TKR, and 6-, 12-, and 24-months after TKR with parametric and nonparametric analyses including one-sample t-tests, Wilcoxon rank sum, and Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact test of proportions, as appropriate. All tests will be two-sided (unless otherwise stated) and the overall type I error will be maintained at 5%.

We will use linear and generalized linear mixed effects regression models to analyze the repeated measures of all outcomes. Although a significant treatment*time interaction will conclude rejection of the hypothesis, in this pilot study we will focus on obtaining estimates of baseline adjusted treatment effects at the end of treatment as preliminary evidence of effectiveness to power a future trial. We will correct the inflation of the type I error due to multiple primary outcomes using Holm’s stepdown procedure. Due to the exploratory nature of the secondary outcomes, we will not adjust the type I error. Our mixed models provide valid inferences when data are missing at random. However, we will also test the plausibility of this assumption and repeat our analysis using pattern-mixture models [65].

Data management

All data will be collected using REDCap. Research staff will code all data fields to identify queries generated by REDCap and address them appropriately. Research staff will receive a unique login and password for the REDCap system and will be able to view and verify data accuracy. All participant data will be stored on secure HSS and WCM network servers.

Monitoring

As this study is a behavioral intervention with a small sample size, a data monitoring committee will not be used. Interim analyses will not be conducted.

Ethics and dissemination

Important protocol modifications will be communicated to all relevant parties including investigators, trial participants, regulatory bodies, and the trial registry. The research team will protect participant confidentiality by: (i) removing direct identifiers from stored information [(i.e., names, social security numbers, medical record numbers)]; (ii) securing and limiting access to information that would identify participants; and (iii) limiting access to information stored to HSS and WCM investigators. Data will be stored on password protected network servers at HSS and WCM and the use of REDCap ensures the secure collection of data from participants. Peer coaches will not be collecting any data and will receive appropriate protected health information training.

The final data set will be stripped of identifiers prior to release for sharing. Study data and associated documentation will be made available to researchers after approval from respective institutional review boards and under the following rules: a) the requestor shall provide resources for data transfer; b) the data is used for research purposes only; c) appropriate data security measures are taken by the requester. Trial results will be available to participants, healthcare professionals, and the public through press release and publications.

Discussion

The Moving Well intervention is a highly innovative intervention that aims to improve mental and physical health before and after TKR. In this pilot, we will be studying the effect of Moving Well on mediating factors of pain and low self-efficacy, high levels of anxiety, and depression. Once we have tested the feasibility of Moving Well and pilot-tested the effectiveness of the intervention, we will then prepare for a large-scale multi-site clinical trial to test its effectiveness in decreasing post-TKR pain in a fully powered trial.

Moving Well was adapted from the Living Healthy intervention [50], which was a peer coach intervention for patients with diabetes to improve musculoskeletal pain. As demonstrated by the original Living Healthy intervention trial, peer coaches can enhance adherence with home exercises and physical activity [50]. Peer coaches can serve to overcome the shortcomings of pre-hab programs. These shortcomings include the requirement for in-person physical therapy, which limits adherence to the pre-hab program, and increased cost of the intervention due to having an actual physical therapist to conduct the exercises [24, 25, 66]. The lower cost of peer coaches could help with the scale-up of physical therapist-delivered interventions, which can be too costly. Similarly, private insurance companies, including Medicaid, are covering costs for peer coach services, which will serve to support the scale-up of the intervention and enable it to be available to everyone beyond research purposes [67, 68].

Several studies have shown strong associations between anxiety, depression, and procedure expectations with TKR outcomes [5, 15, 19,20,21]. These associations were independent of other factors associated with persistent pain and low physical function after TKR. As previous studies have shown that physical pre-habilitation alone is not enough to improve post-TKR pain, Moving Wellwill target anxiety, depressive symptoms, and physical fitness both before and after TKR. The pre-TKR program focuses on increasing participants’ self-efficacy in performing rehabilitation exercises with the goal of decreasing their fear of exercise because of knee pain after their TKR. This mental preparation will consist of participants using principles of CBT, increasing their self-awareness on how their pain affects their mood and vice versa. This will be followed by creating strategies to change these disruptive thoughts or behaviors so that they can increase their self-efficacy in engaging in physical activity and rehabilitation exercises despite their pain. At the same time, a systematic review showed that the professional qualifications of trained coaches delivering structured online programs based on these principles are of minor importance in terms of the efficacy of these interventions [69]. Hence, the rationale for the use of peer coaches in the Moving Well intervention.

Innovations

The innovations of this study include 1) the heavy emphasis on patient-centeredness and a multi-stakeholder participatory model for the design and development of all materials; 2) the use of peer coaches for patients scheduled to undergo TKR; 3) the use of principles of CBT (positive thinking) to prepare for and recover from TKR; 4) A pre-surgery at-home exercise program; 5) employment of cost-effective personnel (peer coaches), overcoming a significant barrier for the scale-up of physical therapist-delivered interventions.

The intervention will be designed to be patient friendly as it is being developed with the direct input of the peer coaches who have a history of knee OA and TKR. These innovative aspects of this project could change the current treatment paradigm for patients undergoing TKR.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the evidence-based nature of the Moving Well peer coach intervention. Another strength is that it is an adaptation of a previously effective intervention called Living Healthy, whose investigators are part of this team (MMS). Moving Well is informed by a theoretical framework (Social Cognitive Theory) as described previously, and the use of an implementation framework (RE-AIM) to guide evaluation will increases the likelihood of effectiveness and implementation. Participants recruited for the study will include those of low socioeconomic status defined as being beneficiaries of Medicaid or on no insurance, and those from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups, which will potentially reveal barriers to the scale-up of this intervention and guide future clinical trial design.

Limitations include the small sample size, although this is to be expected in a pilot study. Another limitation is the requirement for participants to speak English, and have access to a computer, the internet, and a working phone, which means that non-English speaking patients from minority populations, or those who can’t afford a computer, phone, or access to the internet will not be recruited. This may impact the generalizability of the results of the intervention. However, future scale-up of the clinical trial will include translated intervention materials in Spanish and loan internet-equipped devices for participants without internet to be able to access all online materials.

Conclusion

This highly innovative study will help develop a foundation for a future larger trial that can leverage significant strategies to improve the preparation and recovery from TKR surgery. It can also help in the development of future interventions targeted at patients managing their chronic KOA pain who are not candidates for TKR or that are not interested in the procedure. Finally, we expect that it will be of general help in addressing health care challenges for people with chronic diseases such as KOA.

Availability of data and materials

Data for the study design can be found in the manuscript figures, tables, and supplementary materials. For further information on study design, please email the corresponding author, Iris Navarro-Millán, MD MSPH at yin9003@med.cornell.edu.

Abbreviations

- 6MWT:

-

6 Minute Walk Test

- ADL:

-

Activities of Daily Living

- CBT:

-

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- CONSORT:

-

CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- GAD-7:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7

- GSE:

-

General Self-Efficacy Scale

- HSS:

-

Hospital for Special Surgery

- KOA:

-

Knee Osteoarthritis

- KOOS:

-

Knee Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

- KOOS-ADL:

-

Knee Osteoarthritis Outcome Score-Activities of Daily Living

- LSNS-18:

-

Lubben Social Network Scale-18

- MoI:

-

Motivational Interviewing

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- OARS:

-

Open-ended questions, Affirmation, Reflective Listening, Summary

- PALS:

-

Patient Activated Learning System

- PCS:

-

Pain Catastrophizing Scale

- PHQ-8:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-8

- Pre-hab:

-

Prehabilitation

- PROMIS:

-

Patient-Reported Outcomes Information System

- RE-AIM:

-

Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance

- REDCap:

-

Research Electronic Data Capture

- RKO:

-

Renewable Knowledge Objects

- SCT:

-

Social Cognitive Theory

- SF-12:

-

12-Item Short Form Survey

- TKR:

-

Total Knee Replacement

- TUG:

-

Timed Up and Go test

- WCM:

-

Weill Cornell Medicine

References

Cisternas MG, Murphy L, Sacks JJ, Solomon DH, Pasta DJ, Helmick CG. Alternative Methods for Defining Osteoarthritis and the Impact on Estimating Prevalence in a US Population-Based Survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(5):574–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22721.

Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000435. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000435.

Hawker G, Wright J, Coyte P, et al. Health-related quality of life after knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(2):163–73. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-199802000-00003.

Heck DA, Robinson RL, Partridge CM, Lubitz RM, Freund DA. Patient outcomes after knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;356:93–110. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-199811000-00015.

Ayers DC, Franklin PD, Ploutz-Snyder R, Boisvert CB. Total knee replacement outcome and coexisting physical and emotional illness. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;440:157–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000185447.43622.93.

Bass AR, McHugh K, Fields K, Goto R, Parks ML, Goodman SM. Higher Total Knee Arthroplasty Revision Rates Among United States Blacks Than Whites: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(24):2103–8. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.15.00976.

Dave AJ, Selzer F, Losina E, et al. Is there an association between whole-body pain with osteoarthritis-related knee pain, pain catastrophizing, and mental health? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(12):3894–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-015-4575-4.

Feldman CH, Dong Y, Katz JN, Donnell-Fink LA, Losina E. Association between socioeconomic status and pain, function and pain catastrophizing at presentation for total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0475-8.

Foran JR, Mont MA, Etienne G, Jones LC, Hungerford DS. The outcome of total knee arthroplasty in obese patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(8):1609–15. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-200408000-00002.

Goodman SM, Mandl LA, Parks ML, et al. Disparities in TKA Outcomes: Census Tract Data Show Interactions Between Race and Poverty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(9):1986–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-4919-8.

Goodman SM, Parks ML, McHugh K, et al. Disparities in Outcomes for African Americans and Whites Undergoing Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Literature Review. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(4):765–70. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.150950.

Kerkhoffs GM, Servien E, Dunn W, Dahm D, Bramer JA, Haverkamp D. The influence of obesity on the complication rate and outcome of total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis and systematic literature review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(20):1839–44. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.K.00820.

Lefebvre MF. Cognitive distortion and cognitive errors in depressed psychiatric and low back pain patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1981;49(4):517–25. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.49.4.517.

McIsaac DI, Beaulé PE, Bryson GL, Van Walraven C. The impact of frailty on outcomes and healthcare resource usage after total joint arthroplasty: a population-based cohort study. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-b(6):799–805. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.98b6.37124.

Riddle DL, Golladay GJ, Hayes A, Ghomrawi HMK. Poor expectations of knee replacement benefit are associated with modifiable psychological factors and influence the decision to have surgery: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study of a community-based sample. Knee. 2017;24(2):354–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2016.11.009.

Riddle DL, Wade JB, Jiranek WA, Kong X. Preoperative pain catastrophizing predicts pain outcome after knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(3):798–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-009-0963-y.

Santaguida PL, Hawker GA, Hudak PL, et al. Patient characteristics affecting the prognosis of total hip and knee joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. Can J Surg. 2008;51(6):428–36.

Severeijns R, Vlaeyen JW, van den Hout MA, Weber WE. Pain catastrophizing predicts pain intensity, disability, and psychological distress independent of the level of physical impairment. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(2):165–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002508-200106000-00009.

Sullivan M, Tanzer M, Reardon G, Amirault D, Dunbar M, Stanish W. The role of presurgical expectancies in predicting pain and function one year following total knee arthroplasty. Pain. 2011;152(10):2287–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.06.014.

Sullivan M, Tanzer M, Stanish W, et al. Psychological determinants of problematic outcomes following Total Knee Arthroplasty. Pain. 2009;143(1–2):123–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.011.

Vissers MM, Bussmann JB, Verhaar JA, Busschbach JJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Reijman M. Psychological factors affecting the outcome of total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41(4):576–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.07.003.

Monticone M, Ferrante S, Rocca B, et al. Home-based functional exercises aimed at managing kinesiophobia contribute to improving disability and quality of life of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(2):231–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2012.10.003.

Wylde V, Dennis J, Gooberman-Hill R, Beswick AD. Effectiveness of postdischarge interventions for reducing the severity of chronic pain after total knee replacement: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e020368. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020368.

Ackerman IN, Bennell KL. Does pre-operative physiotherapy improve outcomes from lower limb joint replacement surgery? A systematic review Aust J Physiother. 2004;50(1):25–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60245-2.

Moyer R, Ikert K, Long K, Marsh J. The Value of Preoperative Exercise and Education for Patients Undergoing Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JBJS Rev. 2017;5(12):e2. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.Rvw.17.00015.

Wang AW, Gilbey HJ, Ackland TR. Perioperative exercise programs improve early return of ambulatory function after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81(11):801–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002060-200211000-00001.

Beck AT. Cognitive Therapy: Nature and Relation to Behavior Therapy - Republished Article. Behav Ther. 2016;47(6):776–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.003.

Beck JS. Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. p. xix, 391.

McCurry SM, Zhu W, Von Korff M, et al. Effect of Telephone Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia in Older Adults With Osteoarthritis Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):530–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.9049.

Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, Roberts C, Creed F. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):902–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61400-2.

Thorn BE, Pence LB, Ward LC, et al. A randomized clinical trial of targeted cognitive behavioral treatment to reduce catastrophizing in chronic headache sufferers. J Pain. 2007;8(12):938–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2007.06.010.

Allen KD, Oddone EZ, Coffman CJ, et al. Patient, Provider, and Combined Interventions for Managing Osteoarthritis in Primary Care: A Cluster Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(6):401–11. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-1245.

Allen KD, Yancy WS Jr, Bosworth HB, et al. A Combined Patient and Provider Intervention for Management of Osteoarthritis in Veterans: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(2):73–83. https://doi.org/10.7326/m15-0378.

Buvanendran A, Sremac AC, Merriman PA, Della Valle CJ, Burns JW, McCarthy RJ. Preoperative cognitive-behavioral therapy for reducing pain catastrophizing and improving pain outcomes after total knee replacement: a randomized clinical trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2021;46(4):313–21. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2020-102258.

Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1.

Andreae SJ, Andreae LJ, Cherrington AL, et al. Peer coach delivered storytelling program improved diabetes medication adherence: A cluster randomized trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2021;104:106358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2021.106358.

Fisher EB Jr, Strunk RC, Sussman LK, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of a community approach to asthma management: the Neighborhood Asthma Coalition (NAC). J Asthma. 1996;33(6):367–83. https://doi.org/10.3109/02770909609068182.

Horvath KJ, Oakes JM, Rosser BR, et al. Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of an online peer-to-peer social support ART adherence intervention. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):2031–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0469-1.

Shah S, Peat JK, Mazurski EJ, et al. Effect of peer led programme for asthma education in adolescents: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322(7286):583–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7286.583.

Tang TS, Funnell M, Sinco B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of peer leaders and community health workers in diabetes self-management support: results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1525–34. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-2161.

Tang TS, Funnell MM, Gillard M, Nwankwo R, Heisler M. Training peers to provide ongoing diabetes self-management support (DSMS): results from a pilot study. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(2):160–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.013.

Tang TS, Funnell MM, Gillard M, Nwankwo R, Heisler M. The development of a pilot training program for peer leaders in diabetes: process and content. Diabetes Educ Jan-Feb. 2011;37(1):67–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721710387308.

Thom DH, Ghorob A, Hessler D, De Vore D, Chen E, Bodenheimer TA. Impact of peer health coaching on glycemic control in low-income patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med Mar-Apr. 2013;11(2):137–44. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1443.

Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski J, Nishikawa B, et al. Outcomes of community health worker interventions. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2009;181:1–144 (A1-2, B1-14, passim).

Young SD, Zhao M, Teiu K, Kwok J, Gill H, Gill N. A social-media based HIV prevention intervention using peer leaders. J Consum Health Internet. 2013;17(4):353–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/15398285.2013.833445.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–7. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Bmj. 2010;340:c332. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c332.

Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):200–7. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583.

Carmel AS, Cornelius-Schecter A, Frankel B, et al. Evaluation of the Patient Activated Learning System (PALS) to improve knowledge acquisition, retention, and medication decision making among hypertensive adults: Results of a pilot randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(8):1467–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.03.001.

Andreae SJ, Andreae LJ, Richman JS, Cherrington AL, Safford MM. Peer-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Training to Improve Functioning in Patients With Diabetes: A Cluster-Randomized Trial. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(1):15–23. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2469.

Safford MM, Andreae S, Cherrington AL, et al. Peer Coaches to Improve Diabetes Outcomes in Rural Alabama: A Cluster Randomized Trial. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13 Suppl(Suppl 1):S18-26. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1798.

Andreae SJ, Andreae LJ, Cherrington AL, et al. Development of a Community Health Worker-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Training Intervention for Individuals With Diabetes and Chronic Pain. Fam Community Health Jul-Sep. 2018;41(3):178–84. https://doi.org/10.1097/fch.0000000000000197.

Miller WR. Motivational interviewing: research, practice, and puzzles. Addict Behav Nov-Dec. 1996;21(6):835–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(96)00044-5.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092.

Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1–3):163–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026.

Lubben J. Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Family & community health. J Health Promot Maintenance. 1988;11;42–52.

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003.

Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:524–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524.

Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, Ekdahl C, Beynnon BD. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)–development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28(2):88–96. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.1998.28.2.88.

Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Generalized self-efficacy scale. In: J. Weinman SW, Johnston M, editors. Measures in health psychology: a user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs. Windsor, United Kingdom: NFER-Nelson, 1995;1;35–37.

Buysse DJ, Yu L, Moul DE, et al. Development and validation of patient-reported outcome measures for sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairments. Sleep. 2010;33(6):781–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/33.6.781.

Balke B. A Simple field test for the assessment of physical fitness. Oklahoma city: Civil aeromedical research institute; 1963. p. 1–8. Rep 63–6.

Eekhof JA, De Bock GH, Schaapveld K, Springer MP. Short report: functional mobility assessment at home. Timed up and go test using three different chairs. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:1205–7.

Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Development and validation of criterion-referenced clinically relevant fitness standards for maintaining physical independence in later years. Gerontologist. 2013;53(2):255–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns071.

Little RJ, Wang Y. Pattern-mixture models for multivariate incomplete data with covariates. Biometrics. 1996;52(1):98–111.

Calatayud J, Casaña J, Ezzatvar Y, Jakobsen MD, Sundstrup E, Andersen LL. High-intensity preoperative training improves physical and functional recovery in the early post-operative periods after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(9):2864–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-016-3985-5.

Integrating Peers into Treatment Programs in New York City. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Accessed 21 Jul 2022. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/mh/peers-treatment-programs.pdf.

MACPAC. Medicaid Coverage of Community Health Worker Services. Accessed 21 Jul 2022. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Medicaid-coverage-of-community-health-worker-services-1.pdf.

Baumeister H, Reichler L, Munzinger M, Lin J. The impact of guidance on Internet-based mental health interventions — A systematic review. Internet Interv. 2014;1(4):205–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2014.08.003.

Acknowledgements

Clay Woodland Englehart, Sentia Weche, Katerina Fishman, Fernando Navarro-Millán, Paola Báez-Rivera, and patients that participated in the formative work and the exercise videos. Dr. Lisa Mandl, for her assistance in the formative work for this study. Rebecca Seguin-Fowler for allowing us to adapt her intervention into the active control arm and Susan Andreae who shared the Living Healthy materials for us to adapt it into Moving Well. Thank you to Drs. Thomas Sculco, Peter Sculco, Mathias Bostrom, Jose Rodriguez, Gwo-Chin Lee, and Fred Cushner for their assistance with the recruitment of participants.

Funding

This work was supported by INM’s Innovative Research Award from the Rheumatology Research Foundation. INM was funded by the K23AR068449 award from NIAMS, NIH. The funding body was not involved in the study design, data collection, analysis, data interpretation, or manuscript development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

INM and MMS conceived the study idea and secured funding. INM, AJ, YDP, MB, GL, WKH, NH, MP, ADV, SG, SB, and MMS were involved with protocol design and implementation. INM and AJ drafted the manuscript. A.J. and Y.D.P. prepared all figures, tables, and supplemental materials. YDP, MB, GL, WKH, NH, MP, ADV, SG, SB, and MMS provided edits to the manuscript. All authors approved the final version for publication.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experiments will be performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (such as the Declaration of Helsinki). The ethic committee of the Hospital for Special Surgery protocol number #2019–1298 approved this study. All participants completed an informed consent form before participating in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

INM received speaker fees from SOBI. AJ, YDP, MB, GL, WKH, NH, MP, AGDV, SG, SB, and MS do not have any competing interests that may be perceived to influence the results and/or discussion reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Peer Coach Evaluation Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jabri, A., Domínguez Páez, Y., Brown, M. et al. A single-center, open-label, randomized, parallel-group trial to pilot the effectiveness of a peer coach behavioral intervention versus an active control in reducing anxiety and depression in patients scheduled for total knee replacement. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 24, 353 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-06460-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-06460-4