Abstract

Background

Knee osteoarthritis was reported as the second most prevalent condition in the national musculoskeletal survey. The purpose of this extended study was to identify risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in Bangladeshi adults.

Methods

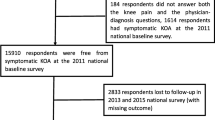

This cross-sectional study was conducted in rural and urban areas of Bangladesh using stratified multistage cluster sample of 2000 adults aged 18 years or older recruited at their households. The Modified Community Oriented Program for Control of Rheumatic Disorders (COPCORD) questionnaire was used to collect data. The diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis was made using the decision tree clinical categorization criteria of the American College of Rheumatology. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were done to identify the risk factors for knee osteoarthritis.

Results

A total of 1843 individuals (892 men and 951 women) participated, and 134 had knee osteoarthritis yielding a prevalence of 7.3% (95% confidence interval (CI) 4.9 to 9.6%). The mean (standard deviation) age of the knee osteoarthritis patients was 51.7 (11.2) years. Multivariate logistic regression analysis found a significant association with increasing age (≥38 years OR 8.9, 95% CI 4.8–16.5; ≥58 years OR 13.9, 95% CI 6.9–28.0), low educational level (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.0–2.7) and overweight (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2–2.9) with knee osteoarthritis. Knee osteoarthritis patients had a high likelihood of having work loss preceding 12 months (age and sex-adjusted OR 2.3; 95% CI 1.4–3.8; P < 0.01).

Conclusions

Knee osteoarthritis is a commonly prevalent musculoskeletal problem among Bangladeshi adults having link to work loss. Increasing age, low education and overweight are significant risk factors of knee osteoarthritis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Knee osteoarthritis is a common progressive joint disease and is characterized by chronic pain and functional disability [1]. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 knee osteoarthritis was a major public health issue [2]. The worldwide prevalence of symptomatic osteoarthritis over the age of women 60 years is 9.6% in men and 18% in women. The majorities (80%) of patients with knee osteoarthritis have limitations in movement, and 25% cannot perform their major daily activities of life [3]. Among the patients with osteoarthritis, knee involvement is more prevalent [2].

The global prevalence of knee osteoarthritis was 16% in individuals aged 15 years and above and 22.9% in individuals aged 40 years and above. It corresponded to around 654.1 million individuals (40 years and above) with knee osteoarthritis in 2020 worldwide [4]. Population-based cohort studies showed that knee osteoarthritis is an independent risk factor of work loss or disability [5]. In 2019 globally osteoarthritis was the 15th highest cause of years lived with disability [6].

Knee osteoarthritis is more prevalent with the increasing age and in females [7], low educational, socioeconomic achievements [8,9,10], those living in rural areas [8, 9]. Other risk factors include genetic susceptibility, obesity, trauma/mechanical forces, muscle weakness, joint laxity, kneeling, squatting, and meniscal injuries [11]. Two other systematic reviews [6, 12] identified obesity, previous knee trauma, hand OA, female gender, and older age as risk factors. There are reports that genetic inheritance, knee-bones shape abnormality, and diabetes are associated with knee osteoarthritis [13,14,15]. People enduring heavy manual occupations [16], or intensive exercise [17] have an increased risk of knee osteoarthritis. Researchers from Bangladesh and Iran prepared a long list of probable risk factors for osteoarthritis [5], which included most of the factors mentioned above. However, it is understandable that using a long list of variables in large population-based studies may not be realistic.

In 1981, World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Community Oriented Programme for Control of Rheumatic Disorders (COPCORD). Following launching this programme many countries in the Asia Pacific [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30] and Latin America [31, 32] completed COPCORD studies. We reported prevalence and risk factors of musculoskeletal conditions in our first nationwide survey done in 2015 [33]. In this paper, we aimed at identifying the risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in Bangladeshi adults.

Methods

Study design and participants

This national survey used a stratified (urban and rural) multi-stage cluster sample for selecting 2000 adults (18 years or older) in their households using primary sampling units of the national census sampling frame. The details of the methods of this survey were given elaborately in it its original publications [33]. Briefly, we have presented here methods related to the estimation of prevalence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis. Knee osteoarthritis was diagnosed according to the decision tree version [34] of the original criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) s as suggested by Skou et al. [35]. The diagnoses were based on the presence of knee pain plus any of the following three groups of criteria:

-

1)

Crepitus, morning knee stiffness of 30 min or less, and age of 38 years or above

-

2)

Crepitus, morning stiffness of longer than 30 min, and bony enlargement

-

3)

No crepitus, but bony enlargement.

Instrument and data collection

Data were collected by interviewers using a modified COPCORD questionnaire. A subject was considered as a positive respondent if he/she reported occurrence of pain and or swelling at one or both knees at least in the preceding 7 days. Subjects who did not report pain and or swelling on those 7 days but were taking prescribed medicines for relieving pain, e.g., non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or steroids, were also included. Respondents in whom the knee pain appeared, developed, and disappeared during the preceding 7 days were also labeled as positive respondents.

Following variables were assessed for analysis: area of residence, sex, age, education, occupation, wealth index (constructed out of household asset items), body mass index (BMI), history of trauma, smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), and physical activities (Based on metabolic equivalents, categorized into quartiles; the fourth quartile being defined as strenuous physical activity.). These risk factors were determined primarily based on the study done by Haq et al. [5] and based on several other studies [6, 12,13,14, 18, 19, 36, 37].

Disability was scored with a validated Bangla version of the Health Assessment Questionnaire (B-HAQ) [38]. The worst score in each of the 8 domains are first added and the sum total was divided by 8 to create a B-HAQ Disability index (B-HAQ-DI), yielding a total disability score of 0–3, where zero is no disability and 3 is a severe disability [39, 40]. To assess work loss, a 12-month recall cycle was used. All participants were asked whether they had to stop their usual paid or unpaid (for example, homemakers) occupational work, due to MSK conditions or related pain. Duration of such work losses (in days) was recorded. Further details and definitions of different variables will be found in the original survey report [33].

Statistical analysis

All quantitative variables were categorized before analysis. The data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and transferred to Epi Info (version 7) and SPSS (version 21) for analysis. The age standardized prevalence was calculated from the World Health Organization’s new world standard population 2000–2025 [41]. 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for all prevalence estimates related to knee osteoarthritis and presented based on sex stratification. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were done to identify the possible risk factors for knee osteoarthritis. Age and sex-adjusted odds ratios were obtained to examine whether knee osteoarthritis was associated with work loss in the preceding 12 months.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

During the study, the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical criteria were followed [42]. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University. Written (or thumb impression if unable to write) informed consent was obtained from the respondents in Bangla as per guidelines of Institutional Review Board.

Results

This study included a total of 1843 participants (892 men and 951 women), of whom 134 (60 men and 74 women) were diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis. The mean (standard deviation) age of individuals with knee osteoarthritis was 51.7 (11.2) years. A half (50%) were female homemakers. More than half (56.8%) came from rural areas, about 70.2% completed elementary or less schooling, only 13.4% engaged in strenuous physical activity around 30% had a body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or more and approximately 13% had a history of diabetes mellitus. Among the patients with knee osteoarthritis, 19.4% had any kind of work loss in the preceding 12 months whereas the median duration of the work loss was 25 (interquartile range 12–90) days. Moreover, 25.4% of individuals with knee osteoarthritis moderate disability from the B-HAQ disability index (B-HAQ-DI) where anyone scoring ≥0.8 were categorized as having a disability (Table 1).

The age-standardized prevalence was 7.7 (95% CI 4.6–10.7); women had a statistically non-significant higher prevalence (11, 95% CI 6.3–15.7) compared to men (5.9, 95% CI 2.7–9.2). There was no statistically significant difference between occupational groups. Knee osteoarthritis prevalence did not vary significantly between urban (8.0, 95% CI 5.0–11.0) and rural (6.8, 95% CI 3.7–10.0) areas. No statistical difference was found between the level of educational achievements, wealth indices, and tobacco use. There was no significant difference between strenuous (5.1, 95% CI 1.4–8.7) and non-strenuous (7.8, 95% CI 5.6–10.0) physical activities. There was also no significant difference between the BMI ≥ 25 Kg/m2 group (10.4, 95% CI 6.5–14.3) and BMI < 25 Kg/m2 group. Prevalence did not vary significantly between those with diabetes (15.6, 95% CI 8.8–22.4) and without diabetes (6.7, 95% CI 4.6–9.0). There was no statistically significant difference between individuals who had a history of trauma (10.1, 95% CI 4.5–15.7) and those who did not (6.9, 95% CI 4.8–9.1) (Table 2).

We found that patients with knee osteoarthritis had 3.2 (95% CI 2.0–5.1) and 2.1 (95% CI 1.3–3.3) times the likelihood of having work loss (last 12 months) and moderate to severe disability, respectively. Adjustment of differences in age and sex using multivariate logistic regression analysis these estimates were a little attenuated 2.3 (95% CI 1.4–3.8) and 1.5 (95% CI 0.9–2.5) for experiencing work loss (last 12 months) and moderate to severe disability, respectively (Table 3).

The univariate logistic regression found a significant relationship of five out of 11 risk factors for knee osteoarthritis. These are increasing age (38 to 57 years: OR 8.9, 95% CI 4.9–16.3; 58 and above: OR 11.7, 95% CI 6.1–22.3), low educational (primary or less) level (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.4–2.9), ever tobacco use (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.0–2.1), overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.2–2.5) and diabetes mellitus (OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.5–4.4). However, in multivariate logistic regression analysis, where all 11 risk factors were included in the model, an increasing age (38 to 57 years: OR 8.9, 95% CI 4.8–16.5; 58 and above: OR 13.9 95% CI 6.9–28.0, low education (primary or less) level (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.0–2.7) and overweight (BMI ≥ 25 Kg/m2) (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2–2.9) were found to be significantly associated with knee osteoarthritis. The model explained only 18.2% variances and age was the major contributor (Table 4).

Discussion

The age-standardized prevalence of knee osteoarthritis was 7.7% in this first-ever national survey of the musculoskeletal survey in Bangladesh. It was lower than that of the global prevalence of 16.0% estimated in a meta-analysis of 88 articles reported from 34 countries [4]. In this meta-analysis, the prevalence of radiological knee osteoarthritis, comprising symptomatic and asymptomatic ones, was 28.7%. Our prevalence estimate was comparable to that of France [43] (7.6%) and America [44] (7.3%) but lower than that of India [45] (28.7%), Japan [46] (30.0%) and Canada [47] (14.2%). However, these estimates should be interpreted with caution, as the studies may differ in terms of design, setting, age and sex group, and, more significantly, the definitions used. Furthermore, because we have used only the clinical classification criteria, the prevalence estimated in the present study may be an underestimate. Peat G et al. [48] concluded that clinical criteria might not be sensitive enough to detect early and mild cases.

We used a less known variant of the ACR criteria [34], instead of the well-known version in which knee pain plus three out of six criteria should be met. This was in line with our previous COPCORD study in Bangladeshi adults [20] that reported occurrence of the knee osteoarthritis much earlier than 50 years of age. Considering the age distribution found in that survey, we presumed that a substantial proportion of patients could remain undetected should the 50 years criterion of the popular ACR criteria [24] be used. The occurrence of knee osteoarthritis before the age of 50 years in other populations [49, 50] is also not rare. Therefore, the choice of the diagnostic criteria would depend on the population-specific age distribution.

Increasing age was a significant risk factor for the development of knee osteoarthritis. Several other studies [11, 28, 43,44,45] also found increasing age as a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis. A low level of education was a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis. Low educational attainment was significantly associated with knee osteoarthritis in a study in North Carolina, USA [10]. People with lower academic achievement usually engage in kneeling, squatting, and weight lifting [51]. These postures and activities rather than the lower education itself might contribute to the development of knee osteoarthritis.

In our study, being overweight was another risk factor for knee osteoarthritis. A population-based study in Spain found an association between overweight and obesity with clinically diagnosed knee osteoarthritis [52]. A study conducted in North Carolina; USA found that the lifetime risk of knee osteoarthritis increased with increasing BMI [53]. A systematic review [54] with 14 studies found that overweight and obesity increased the risk of knee osteoarthritis. Mechanical stress is the key risk factor in obesity-related pathology [55]. Ten percent reduction of weight in knee osteoarthritis patients offered benefits of reducing pain, improvement in function and, improved physical health-related quality of life [56].

The findings on age, sex, education and, overweight, are fairly similar in many countries including China [57], India, Pakistan [58], and Nigeria [59]. We, however, do not have data on kneeling and squatting work exposures, genetic susceptibility, and relevant hormones [60] that might have some impact on our prevalence estimate.

Many studies [28, 40, 61,62,63,64,65] observed significant differences in the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis between urban-rural areas, occupation, educational achievements, socioeconomic status, and people with different physical activities (strenuous versus non-strenuous). However, our study was unable to demonstrate a significant association with these variables. It could be due to some unknown attributes of our population. It is relevant to mention here that the selection of risk factors was not based on any psychometric analysis [66]. A cohort study design might help resolve the issue.

One-fourth of our patients with knee OA had moderate to severe disability and around one-fifth had work loss of various duration. Work loss was significantly associated with knee osteoarthritis when adjusted with age and sex. In a study in the UK one-quarter of the patients with knee OA were severely disabled [67]. In Canada 90% of patients with osteoarthritis had higher risk [hazard ratio 1.90 (95% CI 1.36–3.23)] of work loss due to illness or disability compared with their matched non-OA individuals after adjusting for socio-demographic, health, and work-related status [36].

It was the first nationwide survey on musculoskeletal conditions in Bangladesh. The national representation and the clinical diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis by rheumatology residents, and its (diagnosis) confirmation by expert rheumatologists provided an inherent strength to this study. However, it had limitations too. Radiological investigations could not be done in some cases due to lack of the facilities in some survey areas. Thus, our prevalence estimates have a threat of underestimation of the problem. Missing risk factors such as genetic inheritance, abnormalities in the shape of the bone, muscle weakness, joint laxity, mechanical forces, meniscal tear and hand osteoarthritis were not addressed in our study [5, 6, 11,12,13].

Conclusions

Knee osteoarthritis is a common musculoskeletal disorder in Bangladeshi adults. Increasing age, low educational level, and overweight were independent risk factors for knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis of the knee was significantly associated with substantial work loss in our populations. Future studies should use radiological investigations to get a more accurate burden estimate of knee osteoarthritis. Interventions should focus on healthy aging, overweight, and education of the people in general.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- B-HAQ:

-

Bangla version of the health assessment questionnaire

- B-HAQ-DI:

-

Bangla version of the health assessment questionnaire disability index

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- COPCORD:

-

Community oriented programme for control of rheumatic disorders

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Glyn-Jones S, Palmer A, Agricola R, Price A, Vincent T, Weinans H, et al. Osteoarthritis. Lancet (London, England). 2015;386:376–87.

Safiri S, Kolahi A, Smith E, Hill C, Bettampadi D, Mansournia M, et al. Global, regional and national burden of osteoarthritis 1990-2017: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(6):819–28.

Neogi T. The epidemiology and impact of pain in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2013;21:1145–53.

Cui A, Li H, Wang D, Zhong J, Chen Y, Lu H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29–30:100587.

Haq SA, Davatchi F, Dahaghin S, Islam N, Ghose A, Darmawan J, et al. Development of a questionnaire for identification of the risk factors for osteoarthritis of the knees in developing countries. A pilot study in Iran and Bangladesh. An ILAR-COPCORD phase III study. Int J Rheum Dis. 2010;13:203–14.

Blagojevic M, Jinks C, Jeffery A, Jordan KP. Risk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18:24–33.

Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2019;393:1745–59.

Kang X, Fransen M, Zhang Y, Li H, Ke Y, Lu M, et al. The high prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in a rural Chinese population: the Wuchuan osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:641–7.

Tehrani-Banihashemi A, Davatchi F, Jamshidi A-R, Faezi T, Paragomi P, Barghamdi M. Prevalence of osteoarthritis in rural areas of Iran: a WHO-ILAR COPCORD study. Int J Rheum Dis. 2014;17:384–8.

Callahan LF, Cleveland RJ, Shreffler J, Schwartz TA, Schoster B, Randolph R, et al. Associations of educational attainment, occupation and community poverty with knee osteoarthritis in the Johnston County (North Carolina) osteoarthritis project. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:1–9.

Heidari B. Knee osteoarthritis prevalence, risk factors, pathogenesis and features: part I. Caspian J Intern Med. 2011;2:205–12.

Silverwood V, Blagojevic-Bucknall M, Jinks C, Jordan JL, Protheroe J, Jordan KP. Current evidence on risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23:507–15.

Lespasio M. Knee osteoarthritis: a primer. Perm J. 2017;21:16–183.

Eymard F, Parsons C, Edwards MH, Petit-Dop F, Reginster J-Y, Bruyère O, et al. Diabetes is a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis progression. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23:851–9.

Bhoi T, Kshatri J, Barik SR, Palo SK, Pati S. Knee osteoarthritis in rural elderly of Cuttack district: findings from the AHSETS study. Preprints version; 2021.

Perry TA, Wang X, Gates L, Parsons CM, Sanchez-Santos MT, Garriga C, et al. Occupation and risk of knee osteoarthritis and knee replacement: a longitudinal, multiple-cohort study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50:1006–14.

Michaëlsson K, Byberg L, Ahlbom A, Melhus H, Farahmand BY. Risk of severe knee and hip osteoarthritis in relation to level of physical exercise: a prospective cohort study of long-distance skiers in Sweden. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18339.

Manahan L, Caragay R, Muirden KD, Allander E, Valkenburg HA, Wigley RD. Rheumatic pain in a Philippine village. Rheumatol Int. 1985;5:149–53.

Wigley R, Manahan L, Muirden KD, Caragay R, Pinfold B, Couchman KG, et al. Rheumatic disease in a Philippine village. II: a WHO-ILAR-APLAR COPCORD study, phases II and III. Rheumatol Int. 1991;11:157–61.

Haq SA, Darmawan J, Islam MN, Uddin MZ, Das BB, Rahman F, et al. Prevalence of rheumatic diseases and associated outcomes in rural and urban communities in Bangladesh: a COPCORD study. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:348–53.

Davatchi F, Tehrani Banihashemi A, Gholami J, Faezi ST, Forouzanfar MH, Salesi M, et al. The prevalence of musculoskeletal complaints in a rural area in Iran: a WHO-ILAR COPCORD study (stage 1, rural study) in Iran. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:1267–74.

Moghimi N, Davatchi F, Rahimi E, Saidi A, Rashadmanesh N, Moghimi S, et al. WHO-ILAR COPCORD study (stage 1, urban study) in Sanandaj, Iran. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:535–43.

Darmawan J, Valkenburg HA, Muirden KD, Wigley RD. Epidemiology of rheumatic diseases in rural and urban populations in Indonesia: a World Health Organisation International League Against Rheumatism COPCORD study, stage I, phase 2. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:525–8.

Darmawan J, Muirden KD, Valkenburg HA, Wigley RD. The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis in Indonesia. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32:537–40.

Darmawan J, Valkenburg HA, Muirden KD, Wigley RD. The prevalence of soft tissue rheumatism. A who-ilar copcord study. Rheumatol Int. 1995;15:121–4.

Dans LF, Tankeh-Torres S, Amante CM, Penserga EG. The prevalence of rheumatic diseases in a Filipino urban population: a WHO-ILAR COPCORD study. World Health Organization. International League of Associations for Rheumatology. Community Oriented Programme for the Control of the Rheumatic Diseases. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:1814–9.

Chaiamnuay P, Darmawan J, Muirden KD, Assawatanabodee P. Epidemiology of rheumatic disease in rural Thailand: a WHO-ILAR COPCORD study. Community Oriented Programme for the Control of Rheumatic Disease. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:1382–7.

Farooqi A, Gibson T. Prevalence of the major rheumatic disorders in the adult population of North Pakistan. Rheumatology. 1998;37:491–5.

Chopra A, Patil J, Billempelly V, Relwani J, Tandle HS. Prevalence of rheumatic diseases in a rural population in western India: a WHO-ILAR COPCORD study. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:240–6.

Minh Hoa TT, Damarwan J, Shun Le C, van Hung N, Thi Nhi C, Ngoc An T. Prevalence of the rheumatic diseases in urban Vietnam: a WHO-ILAR COPCORD study. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2252–6.

Peláez-Ballestas I, Sanin LH, Moreno-Montoya J, Alvarez-Nemegyei J, Burgos-Vargas R, Garza-Elizondo M, et al. Epidemiology of the rheumatic diseases in Mexico. A study of 5 regions based on the COPCORD methodology. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2011;86(SUPPL. 86):3–6.

Reyes Llerena GA, Guibert Toledano M, Hernandez Martinez AA, Gonzalez Otero ZA, Alcocer Varela J, Cardiel MH. Prevalence of musculoskeletal complaints and disability in Cuba. A community-based study using the COPCORD core questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18:739–42.

Zahid-Al-Quadir A, Zaman MM, Ahmed S, Bhuiyan MR, Rahman MM, Patwary I, et al. Prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions and related disabilities in Bangladeshi adults: a cross-sectional national survey. BMC Rheumatol. 2020;4(1):69.

Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1039–49.

Skou ST, Koes BW, Grønne DT, Young J, Roos EM. Comparison of three sets of clinical classification criteria for knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study of 13,459 patients treated in primary care. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2020;28:167–72.

Sharif B, Garner R, Sanmartin C, Flanagan WM, Hennessy D, Marshall DA. Risk of work loss due to illness or disability in patients with osteoarthritis: a population-based cohort study. Rheumatology. 2016;55:861–8.

Hunter DJ, March L, Chew M. Osteoarthritis in 2020 and beyond: a lancet commission. Lancet. 2020;396:1711–2.

Islam N, Baron Basak T, Oudevoshaar MAH, Ferdous N, Rasker JJ, Atiqul Haq S. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of a Bengali health assessment questionnaire for use in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:413–7.

Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford health assessment questionnaire: a review of its history, issues, progress, and documentation. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:167–78.

Quintana R, Silvestre AMR, Goñi M, García V, Mathern N, Jorfen M, et al. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders and rheumatic diseases in the indigenous Qom population of Rosario, Argentina. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:5–14.

Ahmad OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, Murray Christopher JL, Lozano R, Inoue M. World (WHO 2000–2025) standard - standard populations - SEER datasets. GPE discussion paper series no.31. 2001. https://seer.cancer.gov/stdpopulations/world.who.html. Accessed 15 Nov 2021.

World Medical Association. WMA declaration of Helsinki – ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects: WMA – The World Medical Association; 2013. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/. Accessed 15 Nov 2021.

Roux CH, Saraux A, Mazieres B, Pouchot J, Morvan J, Fautrel B, et al. Screening for hip and knee osteoarthritis in the general population: predictive value of a questionnaire and prevalence estimates. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1406–11.

Deshpande BR, Katz JN, Solomon DH, Yelin EH, Hunter DJ, Messier SP, et al. Number of persons with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US: impact of race and ethnicity, age, sex, and obesity. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68:1743–50.

Pal CP, Singh P, Chaturvedi S, Pruthi KK, Vij A. Epidemiology of knee osteoarthritis in India and related factors. Indian J Orthop. 2016;50:518–22.

Sudo A, Miyamoto N, Horikawa K, Urawa M, Yamakawa T, Yamada T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in elderly Japanese men and women. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13:413–8.

Birtwhistle R, Morkem R, Peat G, Williamson T, Green ME, Khan S, et al. Prevalence and management of osteoarthritis in primary care: an epidemiologic cohort study from the Canadian primary care sentinel surveillance network. Can Med Assoc Open Access J. 2015;3:E270–5.

Peat G, Thomas E, Duncan R, Wood L, Hay E, Croft P. Clinical classification criteria for knee osteoarthritis: performance in the general population and primary care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1363–7.

Barbour KE, Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Murphy LB, Theis KA, Schwartz TA, et al. Meeting physical activity guidelines and the risk of incident knee osteoarthritis: a population-based prospective cohort study. Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:139–46.

Driban JB, Harkey MS, Barbe MF, Ward RJ, MacKay JW, Davis JE, et al. Risk factors and the natural history of accelerated knee osteoarthritis: a narrative review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):1–1.

Amin S, Goggins J, Niu J, Guermazi A, Grigoryan M, Hunter DJ, et al. Occupation-related squatting, kneeling, and heavy lifting and the knee joint: a magnetic resonance imaging-based study in men. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1645–9.

Reyes C, Leyland KM, Peat G, Cooper C, Arden NK, Prieto-Alhambra D. Association between overweight and obesity and risk of clinically diagnosed knee, hip, and hand osteoarthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ). 2016;68:1869–75.

Murphy L, Schwartz TA, Helmick CG, Renner JB, Tudor G, Koch G, et al. Lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1207–13.

Zheng H, Chen C. Body mass index and risk of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007568.

Chen L, Zheng JJY, Li G, Yuan J, Ebert JR, Li H, et al. Pathogenesis and clinical management of obesity-related knee osteoarthritis: impact of mechanical loading. J Orthop Transl. 2020;24:66–75.

Messier SP, Resnik AE, Beavers DP, Mihalko SL, Miller GD, Nicklas BJ, et al. Intentional weight loss in overweight and obese patients with knee osteoarthritis: is more better? Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70:1569–75.

Liu Y, Zhang H, Liang N, Fan W, Li J, Huang Z, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of knee osteoarthritis in a rural Chinese adult population: an epidemiological survey. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:94.

Iqbal MN, Haidri FR, Motiani B, Mannan A. Frequency of factors associated with knee osteoarthritis. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61:786–9.

Oboirien M, Patrick Agbo S, Olalekan Ajiboye L. Risk factors in the development of knee osteoarthritis in Sokoto, north west, Nigeria. Int J Orthop. 2018;5:905–9.

Hame SL, Alexander RA. Knee osteoarthritis in women. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6:182–7.

Li D, Li S, Chen Q, Xie X. The prevalence of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in relation to age, sex, area, region, and body mass index in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med. 2020;7:304.

Haq SA, Davatchi F. Osteoarthritis of the knees in the COPCORD world. Int J Rheum Dis. 2011;14:122–9.

Hong JW, Noh JH, Kim D-J. The prevalence of and demographic factors associated with radiographic knee osteoarthritis in Korean adults aged ≥ 50 years: the 2010–2013 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0230613.

Stehling C, Lane NE, Nevitt MC, Lynch J, McCulloch CE, Link TM. Subjects with higher physical activity levels have more severe focal knee lesions diagnosed with 3 T MRI: analysis of a non-symptomatic cohort of the osteoarthritis initiative. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18:776–86.

Snoeker B, Turkiewicz A, Magnusson K, Frobell R, Yu D, Peat G, et al. Risk of knee osteoarthritis after different types of knee injuries in young adults: a population-based cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:725–30.

Gaudreault N, Durand M, Moffet H, Hébert L, Hagemeister N, Feldman D, et al. Literature review of risk factors, evaluation instruments, and care and service interventions for knee osteoarthritis. The Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et en sécurité du travail, Montréal; 2015.

Peat G, McCarney R, Croft P. Knee pain and osteoarthritis in older adults: a review of community burden and current use of primary health care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:91–7.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the local health administrations of the survey area, local government field visitors, local people of the survey area, and the participants of the survey.

Funding

World Health Organization (WHO), Bangladesh supported this survey (Agreement Reference: SEBAN140895). WHO, as a part of its mandate to strengthen national research capacity, also provided technical guidance in designing, implementing, analyzing data, and writing the report. However, it does not have any influence on the results. No fund was used for preparing this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Drafting of the manuscript: MZH. All other authors contributed to revise it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. SAH and MMZ had full access to all the data in the study. They are responsible for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study conception and design: SAH, MMZ, MRC, SA, AZ. Acquisition of data: MZH, AZ and SA. Analysis and interpretation of data: RB, MZH, MMZ.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

During the study, the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical criteria were followed. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University. Written (or thumb impression if unable to write) informed consent was obtained from the respondents in Bangla as per guidelines of the Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests declared by the authors. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the writers, and they do not necessarily reflect the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Haider, M.Z., Bhuiyan, R., Ahmed, S. et al. Risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in Bangladeshi adults: a national survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 23, 333 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-05253-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-05253-5