Abstract

Background

To aid design of exercise trials for people with pelvic and lower limb fragility fractures a systematic review was conducted to identify what types of exercise interventions and mobility outcomes have been assessed, investigate intervention reporting quality, and evaluate risk of bias in published trials.

Methods

Systematic searches of electronic databases (CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PEDro) 1996–2019 were conducted to identify randomised controlled trials of exercise for pelvic or lower limb fragility fractures. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts. One reviewer extracted data, a second verified. Two reviewers independently assessed risk of bias. Intervention reporting quality was based on TIDieR, assessed by one reviewer and verified by a second. Narrative synthesis was undertaken. Registration: PROSPERO CRD42017060905.

Results

Searches identified 37 trials including 3564 participants, median sample size 81 (IQR 48–124), participants aged 81 years (IQR 79–82) and 76% (2536/3356) female. All trials focussed on people with hip fracture except one on ankle fracture. Exercise types focussed on resistance exercise in 14 trials, weight bearing exercise in 5 trials, 13 varied dose of sessions with health professionals, and 2 trials each focussed on treadmill gait training, timing of weight bearing or aerobic exercise. 30/37 (81%) of trials reported adequate sequence generation, 25/37 (68%) sufficient allocation concealment. 10/37 (27%) trials lacked outcome assessor blinding. Of 65 exercise interventions, reporting was clear for 33 (51%) in terms of when started, 61 (94%) for where delivered, 49 (75%) for who delivered, 47 (72%) for group or individual, 29 (45%) for duration, 46 (71%) for session frequency, 8 (12%) for full prescription details to enable the exercises to be reproduced, 32 (49%) clearly reported tailoring or modification, and 23 (35%) reported exercise adherence. Subjectively assessed mobility was assessed in 22/37 (59%) studies and 29/37 (78%) used an objective measure.

Conclusions

All trials focussed on hip fracture, apart from one ankle fracture trial. Research into pelvic and other lower limb fragility fractures is indicated. A range of exercise types were investigated but to date deficiencies in intervention reporting hamper reproducibility. Adoption of TIDieR and CERT guidelines should improve intervention reporting as use increases. Trials would be improved by consistent blinded outcome assessor use and with consensus on which mobility outcomes should be assessed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Fragility fractures result from low-energy trauma, usually a fall from standing height or lower. Each year 300,000 people attend UK NHS hospitals with a fragility fracture related to bone insufficiency in older age [1]. This represents a major health, social and economic problem, with an estimated annual cost of £1.8 billion [2]. Lower limb fragility fractures can have a devastating impact, resulting in mobility problems and loss of independence [3].

A core component of rehabilitation after fragility fracture is exercise prescription. A previous systematic scoping review of exercise prescription for people with any type of fragility fracture included studies up to 2009 [4]. While the scale of that review provided a comprehensive overview of exercise interventions at the time, an updated and more focussed systematic review was indicated to inform the development of future interventions for this patient group.

To the best of our knowledge no reviews to date have examined the quality of intervention reporting in trials involving people with lower limb fragility fractures. In other areas of exercise rehabilitation, limitations in reporting that prevent replication in other trials or implementation into clinical practice have been identified [5, 6]. It is therefore important to identify not only what exercise interventions have been assessed but also to establish if reporting of lower limb fragility fracture trials have similar issues in reporting quality, and if so, what areas of reporting are in greatest need of improvement to enable replicability and implementation. Exercise targets improvement in mobility after lower limb fragility fracture and this is a core outcome domain in this patient group, [7] therefore it is also important to identify what outcome measures have been used.

The overall purpose of our review was to provide evidence to guide future exercise intervention development and evaluation for people with pelvic and lower limb fragility fractures and to highlight areas of study design and intervention reporting that could be enhanced to improve the quality, replicability and implementation of future trials. Our aims were to identify the types of exercise interventions that have been tested in randomised clinical trials, investigate the reporting quality of exercise interventions, describe which mobility outcome measures have been used, and evaluate the risk of bias in the trial design and conduct.

Methods

This systematic review was registered on the PROSPERO database (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php? ID = CRD42017060905) and reported according to PRISMA guidance [8].

Eligibility

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials or quasi-randomised controlled trials were considered eligible.

Types of participants

Studies involving adults (50 years or older) within one year of a pelvic or lower limb fracture initially treated surgically or conservatively were included. Studies were excluded if participants were younger (aged under 50 years old), unless separate data for older adults were available, or the proportion of younger adults was small (less than 10%) and, preferably, numbers balanced between the groups.

Types of interventions

Trials comparing different prescribed exercise regimes against each other, or prescribed exercise versus a comparator intervention such as rest, immobilisation in a brace, cast or splint, advice only, or ‘usual care’ were eligible. Exercise prescription encompassed planned physical activity, exercise or active rehabilitation prescribed by a physician, physical therapist or occupational therapist, or other allied health professional [4].

Types of outcomes

We extracted data on which outcome measures of mobility were used in the trials both in terms of subjectively assessed measures of mobility (e.g. Lower Extremity Functional Scale) and objective clinical measures of mobility (e.g. timed walking tests). Duration and timing of follow-up were also extracted.

Search strategy for identification of studies

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). We did not apply language restrictions to the searches. Studies published in 1996 or later were included. Searches were completed April 2019 and updated in MEDLINE and EMBASE in July 2019. Reference lists of included trials were checked for potentially eligible studies. An example search strategy is available in the online supplementary file.

Selection of studies

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts using Covidence software (Covidence, Australia). We obtained full reports of potentially eligible studies, and both reviewers independently performed study selection. If agreement was not achieved by discussion at any stage, a third review author adjudicated. Articles for inclusion were limited to those written in English and published in academic journals.

Data extraction

One author extracted data using a standard data extraction form and a second author checked the extracted data against the source while tabulating the data. The data extraction form was piloted and then modified. The following information was systematically extracted: sample size, sample demographics (age, sex, injury characteristics, time since injury), detailed descriptions of the interventions (including setting, timing, care personnel involved, training, equipment used, weight-bearing, prescription of walking aids, and the type and prescription of exercises used, and assessment of adherence), and the specified mobility outcome measures.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias using Cochrane’s Risk of Bias tool [9]. We used the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Intervention reporting

Reporting quality for the interventions was based on the TIDieR [10] guidance for reporting complex interventions. The quality of intervention reporting was assessed by one reviewer and verified by a second reviewer. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. The criteria for the assessments are shown in Table 1.

Data synthesis

A narrative synthesis was undertaken and interventions were grouped by exercise and fracture type. Characteristics of studies were summarised as counts and percentages for categorical data and medians with interquartile ranges for continuous data.

Changes to protocol

The review focussed on intervention content and reporting quality as these have not been previously assessed in sufficient detail to inform the design and conduct of future trials. The originally planned focus on effectiveness and quantitative meta-analysis was not conducted as this became beyond the scope of resources for the study, and effectiveness meta-analyses are available [11].

Results

Study selection and characteristics

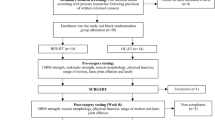

Figure 1 outlines the identification, screening, and inclusion of studies. Searches identified 6308 records. After removal of duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 6016 records were screened. Of these, 184 full-text articles were assessed, and 66 articles reporting 37 trials were eligible.

Characteristics of included studies

Of the 37 included trials, most were conducted in Australia or the USA (18/37, 49%). Trial designs were mostly parallel group (35/37, 95%) with two intervention groups (31/37, 84%), see Table 2 for detailed study characteristics. In total, 3565 participants were randomised across the 37 trials, with a median sample size of 81 (IQR 48 to 124). In 32 trials that provided adequate baseline characteristic data, participants were aged a median of 81 years (IQR 79 to 82) and 76% (2536/3356) were female. All trials focussed on people with a hip fracture except one ankle fracture trial [12] that reported results for a subgroup of participants aged more than 50 years.

Interventions

A range of exercise types were assessed (see Tables 2 and 3), including 14 focussing on resistance exercise, five on weight bearing exercise, 13 varied the dose of sessions with health professions, and two each focussed on treadmill training, timing of weight bearing, or aerobic exercise. These main types of intervention were often combined with other types of exercise, and compared to diverse control interventions (see Table 3).

The setting of exercise intervention delivery was 11 for inpatients, six for outpatients, 13 for community, six were a combination, and for one trial it was unclear what the setting was.

Outcomes

Subjectively assessed mobility outcome measures were used in 22/37 (59%) studies and 29/37 (78%) used an objective mobility measure. There were no common outcome instruments used across the trials. The most frequently used instruments were the Timed Up and Go test (11 trials) and gait speed (11 trials). The length of follow-up was a median of 6 (IQR 2.5 to 12) months.

Risk of bias within included studies

Risk of bias assessments are shown in Table 4. Within the limitations of reporting, it was judged that 30/37 (81%) trials had adequate sequence generation and 25/37 (68%) had sufficient allocation concealment. 10/37 (27%) of trials were at high risk of bias due to a lack of outcome assessor blinding.

Reporting quality of interventions

Of the 37 included trials there were 65 different exercise intervention groups and 16 non-exercise or inactive control comparator groups (see Table 5 for reporting quality assessments). Of the 65 exercise interventions, reporting was judged as being clearly described for 33 (51%) when treatment started after injury, 61 (94%) for where it was delivered, 49 (75%) for who delivered it, 47 (72%) on whether delivered as group or individual, 29 (45%) for the duration of the intervention, 46 (71%) for session frequency, 8 (12%) for the full prescription details to enable the intervention to be reproduced, 32 (49%) clearly reported tailoring or modification, and 23 (35%) reported exercise adherence in the trial. Of the six comparator usual care exercise interventions, only one had more than half of the intervention reporting criteria assessed as being clear.

Discussion

A range of exercise types have been investigated for pelvic and lower limb fragility fractures, with most trials investigating resistance exercise or higher doses of sessions with a health professional. To date deficiencies in reporting of the exercise interventions hamper reproducibility of the interventions, especially in terms of the specific details on how exercises were prescribed. Reporting of usual care exercise comparator interventions was poor. Details on exercise prescription that were most often missed related to the movements performed in the exercises, sets and repetitions for resistance exercises, duration for aerobic exercises, and exercise loading or intensity. Adoption of the TIDieR [10] checklist for reporting complex interventions should improve reporting of future trials. TIDieR was published in 2014, prior to all but five of the 37 trials included in this review. Supplementary use of the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT) [49] is also indicated as these guidelines additionally target the main deficiencies in reporting identified in our review. It is important to recognise that the problems with exercise intervention reporting in pelvic and lower limb fragility fracture trials are consistent with other fields of rehabilitation so these issues are not isolated [5, 6].

One key area of trial design and conduct that could be improved upon in future trials is the blinding of outcome assessors as this was inadequate in 27% of trials and this could be rectified without significant additional resource burden. Blinded outcome assessors are arguably crucial given that the nature of exercise makes it self-evident what intervention is being received, as reflected in our finding that no trial had a low risk of bias assessment for blinding of participants and personnel.

With one exception, all exercise trials for adults with a pelvic or lower limb fragility fractures have been focussed on hip fracture. There is a significant burden from other non-hip fragility fractures as they often require hospitalisation and result in long-term disability, [50] therefore further research for people with pelvic and other lower limb fragility fractures is also needed. Even though most trials have focussed on hip fracture, reflecting their proportionately greater health and socio-economic impact, Sheehan and colleagues [51] have highlighted that rehabilitation trials in this patient group have underrepresented participants with cognitive impairment and nursing home residents, therefore trials focussing on other populations are also indicated.

Previous reviews have included meta-analyses to assess the effectiveness of different exercise interventions [11]. The pooling of outcomes from these trials could be problematic in the context of the intervention heterogeneity and reporting quality limitations outlined in this review. Dealing with heterogeneity in intervention components is a common challenge in quantitative synthesis of complex interventions. One approach that enables an assessment of intervention components is meta-regression, as employed by Diong and colleagues in a review of hip fracture exercise trials, [52] however, there was heterogeneity in the comparator interventions in some of the pooled studies, and there is ongoing debate as to what extent these analytical approaches manage evident clinical variations in intervention components that can interact [53].

Mobility-specific subjective and objective outcome measures were included in 59 and 78% of trials respectively but it is evident within our review that there is inconsistency in the outcome instruments used. The degree of heterogeneity in outcome measure instruments would make quantitative synthesis problematic. Further consensus work towards a core outcome set for rehabilitation trials for people with pelvic and lower limb fragility fractures would therefore be valuable.

This review has some limitations. We included English language and published literature only, meaning that some relevant studies may have been missed. Data extraction and reporting quality was not completely repeated independently by a second reviewer due to the resource limitations of the study. However, a second reviewer did verify these data against the source and any discrepancies corrected in discussion. Finally, as there was no specific intervention reporting quality assessment tool, a review specific assessment was developed drawing on the TIDieR reporting guidelines. A tool for these purposes would be valuable for future research but findings from our assessments provided some clear areas of focus for improving reporting in future exercise trials.

Conclusion

All exercise trials for adults with a pelvic or lower limb fragility fractures have been focussed on hip fracture, apart from one ankle fracture trial. Research for people with pelvic and other lower limb fragility fractures is indicated. A wide range of exercise types have been investigated but to date deficiencies in reporting of the interventions hamper the reproducibility of the interventions, especially in terms of the specific details on how exercises were prescribed. Use of TIDieR and CERT reporting guidelines for future trials will likely improve intervention reporting. Trials of exercise interventions would also be improved by consistent use of blinded outcome assessors and with further consensus on which mobility outcomes should be assessed.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- CENTRAL:

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

- CERT:

-

Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- TIDieR:

-

Template for Intervention Description and Replication

References

British Orthopaedic Association. The care of patients with fragility fracture. London: British Orthopaedic Association; 2007.

Burge RT, Worley D, Johansen A, Bhattacharyya S, Bose U. The cost of osteoporotic fractures in the UK: projections for 2000–2020. J Med Econ. 2001;4(1–4):51–62.

Pasco JA, Sanders KM, Hoekstra FM, Henry MJ, Nicholson GC, Kotowicz MA. The human cost of fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(12):2046–52.

Feehan LM, Beck CA, Harris SR, MacIntyre DL, Li LC. Exercise prescription after fragility fracture in older adults: a scoping review. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(5):1289–322.

Yamato TP, Maher CG, Saragiotto BT, Hoffmann TC, Moseley AM. How completely are physiotherapy interventions described in reports of randomised trials? Physiotherapy. 2016;102(2):121–6.

Negrini S, Arienti C, Pollet J, Engkasan JP, Francisco GE, Frontera WR, Galeri S, Gworys K, Kujawa J, Mazlan M, et al. Clinical replicability of rehabilitation interventions in randomized controlled trials reported in main journals is inadequate. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;114:108–17.

Haywood KL, Griffin XL, Achten J, Costa ML. Developing a core outcome set for hip fracture trials. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-b(8):1016–23.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Bmj. 2009;339:b2535.

Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. London: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008. 1 online resource.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, Altman DG, Barbour V, Macdonald H, Johnston M, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

Handoll HH, Sherrington C, Mak JC. Interventions for improving mobility after hip fracture surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(3):CD001704. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001704.pub4.

Moseley AM, Beckenkamp PB, Haas M, Herbert RD, Lin CW, for the EXACT Team. Rehabilitation after immobilization for ankle fracture: the EXACT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(13):1376–85.

Mangione KK, Craik RL, Tomlinson SS, Palombaro KM. Can elderly patients who have had a hip fracture perform moderate- to high-intensity exercise at home? Phys Ther. 2005;85(8):727–39.

Mangione KK, Craik RL, Palombaro KM, Tomlinson SS, Hofmann MT. Home-based leg-strengthening exercise improves function 1 year after hip fracture: a randomized controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(10):1911–7.

Miller MD, Crotty M, Whitehead C, Bannerman E, Daniels LA. Nutritional supplementation and resistance training in nutritionally at risk older adults following lower limb fracture: a randomized controlled trial [with consumer summary]. Clin Rehab. 2006;20(4):311–23 2006.

Sherrington C, Lord SR. Home exercise to improve strength and walking velocity after hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(2):208–12.

Sylliaas H, Brovold T, Wyller TB, Bergland A. Prolonged strength training in older patients after hip fracture: a randomised controlled trial [with consumer summary]. Age Ageing. 2012;41(2):206–12 2012.

Sylliaas H, Brovold T, Wyller TB, Bergland A. Progressive strength training in older patients after hip fracture: a randomised controlled trial [with consumer summary]. Age Ageing. 2011;40(2):221–7 2011.

Mitchell SL, Stott DJ, Martin BJ, Grant SJ. Randomized controlled trial of quadriceps training after proximal femoral fracture [with consumer summary]. Clin Rehab. 2001;15(3):282–90 2001.

Hauer K, Specht N, Schuler M, Rtsch P, Oster P. Intensive physical training in geriatric patients after severe falls and hip surgery [with consumer summary]. Age Ageing. 2002;31(1):49–57 2002.

Resnick B, Orwig D, Yu-Yahiro J, Hawkes W, Shardell M, Hebel JR, Zimmerman S, Golden J, Werner M, Magaziner J. Testing the effectiveness of the exercise plus program in older women post-hip fracture. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(1):67–76.

Binder EF, Brown M, Sinacore DR, Steger-May K, Yarasheski KE, Schechtman KB. Effects of extended outpatient rehabilitation after hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2004;292(7):837–46.

Peterson MGE, Ganz SB, Allegrante JP, Cornell CN. High-intensity exercise training following hip fracture. Topics Geriatr Rehab. 2004;20(4):273–84.

Latham NK, Harris BA, Bean JF, Heeren T, Goodyear C, Zawacki S, Heislein DM, Mustafa J, Pardasaney P, Giorgetti M, et al. Effect of a home-based exercise program on functional recovery following rehabilitation after hip fracture: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(7):700–8.

Singh NA, Quine S, Clemson LM, Williams EJ, Williamson DA, Stavrinos TM, Grady JN, Perry TJ, Lloyd BD, Smith EU, et al. Effects of high-intensity progressive resistance training and targeted multidisciplinary treatment of frailty on mortality and nursing home admissions after hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:24–30.

Sherrington C, Lord SR, Herbert RD. A randomised trial of weight-bearing versus non-weight-bearing exercise for improving physical ability in inpatients after hip fracture. Aust J Physiother. 2003;49(1):15–22.

Moseley AM, Sherrington C, Lord SR, Barraclough E, St George RJ, Cameron ID. Mobility training after hip fracture: a randomised controlled trial [with consumer summary]. Age Ageing. 2009;38(1):74–80 2009.

Sherrington C, Lord SR, Herbert RD. A randomized controlled trial of weight-bearing versus non-weight-bearing exercise for improving physical ability after usual care for hip fracture. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(5):710–6.

Elinge E, Lofgren B, Gagerman E, Nyberg L. A group learning programme for old people with hip fracture: a randomized study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2003;10:27–33.

Monticone M, Ambrosini E, Brunati R, Capone A, Pagliari G, Secci C, Zatti G, Ferrante S. How balance task-specific training contributes to improving physical function in older subjects undergoing rehabilitation following hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(3):340–51.

Ohoka T, Urabe Y, Shirakawa T. Therapeutic exercises for proximal femoral fracture of super-aged patients: Effect of walking assistance using body weight-supported treadmill training (BWSTT). Physiotherapy (United Kingdom). 2015;101:eS1124–5.

van Ooijen MW, Roerdink M, Trekop M, Janssen TWJ, Beek PJ. The efficacy of treadmill training with and without projected visual context for improving walking ability and reducing fall incidence and fear of falling in older adults with fall-related hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):215.

Ryan T, Enderby P, Rigby AS. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate intensity of community-based rehabilitation provision following stroke or hip fracture in old age. Clin Rehab. 2012;20:123–31.

Crotty M, Killington M, Liu E, Cameron ID, Kurrle S, Kaambwa B, Davies O, Miller M, Chehade M, Ratcliffe J. Should we provide outreach rehabilitation to very old people living in nursing care facilities after a hip fracture? A randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2019;48(3):373–80.

Kimmel LA, Liew SM, Sayer JM, Holland AE. HIP4Hips (high intensity physiotherapy for hip fractures in the acute hospital setting): a randomised controlled trial [with consumer summary]. Med J Aust. 2016;205(2):73–8 2016.

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Platz A, Orav EJ, Stahelin HB, Willett WC, Can U, Egli A, Mueller NJ, Looser S, et al. Effect of high-dosage cholecalciferol and extended physiotherapy on complications after hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(9):813–20.

Tsauo J, Leu W, Chen Y, Yang R. Effects on function and quality of life of postoperative home-based physical therapy for patients with hip fracture. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2005;86(10):1953–7.

Hagsten B, Svensson O, Gardulf A. Early individualized postoperative occupational therapy training in 100 patients improves ADL after hip fracture: a randomized trial. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75(2):177–83.

Martín-Martín LM, Valenza-Demet G, Jimenez-Moleon JJ, Cabrera-Martos I, Revelles-Moyano FJ, Valenza MC. Effect of occupational therapy on functional and emotional outcomes after hip fracture treatment: a randomized controlled trial [with consumer summary]. Clin Rehab. 2013;28(6):541–51 2013.

Tinetti ME, Baker DI, Gottschalk M, Williams CS, Pollack D, Garrett P, Gill TM, Marottoli RA, Acampora D. Home-based multicomponent rehabilitation program for older persons after hip fracture: a randomized trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(8):916–22.

Suwanpasu S, Aungsuroch Y, Jitapanya C. Post-surgical physical activity enhancing program for elderly patients after hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Asian Biomedicine. 2014;8(4):525–32.

Zidén L, Frandin K, Kreuter M. Home rehabilitation after hip fracture a randomized controlled study on balance confidence, physical function and everyday activities [with consumer summary]. Clin Rehab. 2008;22(12):1019–33 2008.

Orwig DL, Hochberg M, Yu-Yahiro J, Resnick B, Hawkes WG, Shardell M, Hebel JR, Colvin P, Miller RR, Golden J, et al. Delivery and outcomes of a yearlong home exercise program after hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):323–31.

Salpakoski A, Törmäkangas T, Edgren J, Kallinen M, Sihvonen SE, Pesola M, Vanhatalo J, Arkela M, Rantanen T, Sipilä S. Effects of a multicomponent home-based physical rehabilitation program on mobility recovery after hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(5):361–8.

Williams NH, Roberts JL, Din NU, Charles JM, Totton N, Williams M, Mawdesley K, Hawkes CA, Morrison V, Lemmey A, et al. Developing a multidisciplinary rehabilitation package following hip fracture and testing in a randomised feasibility study: fracture in the elderly multidisciplinary rehabilitation (FEMuR). Health Technol Assess. 2017;21(44):1–528.

Ali MMI. Influence of early post operative weight bearing on hip function after femoral trochanteric fractures. Bull Faculty Physiother Cairo University. 2010;15(2):69–75.

Oldmeadow LB, Edwards ER, Kimmel LA, Kipen E, Robertson VJ, Bailey MJ. No rest for the wounded: early ambulation after hip surgery accelerates recovery. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(7):607–11.

Mendelsohn ME, Overend TJ, Connelly DM, Petrella RJ. Improvement in aerobic fitness during rehabilitation after hip fracture. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(4):609–17.

Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M, Buchbinder R, Beck B, Bennell K, Brosseau L, Costa L, Cramp F, Cup E, et al. Consensus on exercise reporting template (CERT): modified Delphi study. Phys Ther. 2016;96(10):1514–24.

Keene DJ, Lamb SE, Mistry D, Tutton E, Lall R, Handley R, Willett K. Ankle injury management trial C: three-year follow-up of a trial of close contact casting vs surgery for initial treatment of unstable ankle fractures in older adults. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1274–6.

Sheehan KJ, Fitzgerald L, Hatherley S, Potter C, Ayis S, Martin FC, Gregson CL, Cameron ID, Beaupre LA, Wyatt D, et al. Inequity in rehabilitation interventions after hip fracture: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2019;48(4):489–97.

Diong J, Allen N, Sherrington C. Structured exercise improves mobility after hip fracture: a meta-analysis with meta-regression. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(6):346–55.

Dias S, Sutton AJ, Welton NJ, Ades AE, NICE Decision Support Unit Technical Support Documents. Heterogeneity: Subgroups, Meta-Regression, Bias And Bias-Adjustment. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2012.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Hessam Soutakbar, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Oxford, for contributing to the data extraction stage of the study; Liz Callow, Outreach Librarian, Bodleian Health Care Libraries, University of Oxford, for supporting development and execution of the search strategy; and Sally Hopewell, Associate Professor, University of Oxford, for critical review of the review protocol .

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Funding

This report is independent research supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR Post-Doctoral Fellowship, Dr. David Keene, PDF-2016-09-056). The report was supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford. Professor Lamb receives funding from the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Oxford at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

The funders were not involved in the study design and conduct; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DJK conceived the study concept and led the conduct and reporting. CF led synthesis of the data and reporting quality assessments. PS screened articles and extracted data. MAW extracted data. SEL provided critical feedback on the study protocol and interpretation of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable, systematic review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Keene, D.J., Forde, C., Sugavanam, T. et al. Exercise for people with a fragility fracture of the pelvis or lower limb: a systematic review of interventions evaluated in clinical trials and reporting quality. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21, 435 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03361-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03361-8