Abstract

Background

Dysphagia is considered a complication in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD). However, AECOPD may have risk factors for dysphagia.

Methods

Through a cross-sectional study, which included 100 patients with AECOPD. General information, Pulmonary function, COPD assessment test (CAT) and modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) were collected by questionnaire. The questionnaires were administered by uniform-trained investigators using standard and neutral language, and swallowing risk was assessed by using a water swallow test (WST) on the day of patient admission.

Results

Among the 100 included patients, 50(50%) were at risk of swallowing. Multivariate analysis using logistic regression analysis showed that age ≥ 74 years old, mMRC ≥ level 2, hospitalization days ≥ 7 days and the use of BIPAP assisted ventilation were important influencing factors for swallowing risk in patients with AECOPD.

Conclusion

Patients with AECOPD are at risk for dysphagia, assessing age, mMRC, hospitalization days and the use of BIPAP assisted ventilation can be used to screen for swallowing risk, thus contributing to the implementation of early prevention measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a potentially fatal respiratory condition, is defined by persistently restricted airflow. Its occurrence rises significantly with advancing age [1]. The death rate linked to this condition nearly two folded between 1970 and 2000 [2]. By 2030, it was anticipated that this widely occurring ailment would rank as the third most common cause of mortality and be among the top ten contributors to the overall disease burden [3]. 90% of fatalities occurred in nations with lower and moderate income levels [4, 5].

Between 32.7% and 49% of individuals with COPD experience dysphagia, [6,7,8] and a 33% prevalence of subjective swallowing symptoms in stable COPD [7]. In stable COPD, subjective swallowing symptoms appear to be a prevalent issue. This concern manifests across all phases of the condition, but it is more frequently observed in symptomatic patients and those with reduced physical capacity [7].

Due to the common neuroanatomical mechanisms and pathways involved in respiration and swallowing, precise coordination between them is necessary to protect the airway, which is crucial for safe and effective swallowing function. In addition, both patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) and those with heart disease have symptoms of dyspnea. However, individuals in the former encounter notably higher instances of both self-reported and clinically assessed swallowing dysfunction [9].

Patients with AECOPD experience respiratory and swallowing incompatibility, which may lead to more frequent aspiration and deterioration due to the inability to develop airway protection mechanisms [10]. The incidence of aspiration in COPD is 19.9% [11]. In stable COPD, up to 25% of individuals experience aspiration [12], with an inclination towards elevated rates of hospitalizations and mortality over a period of 36 months [13]. The rate of aspiration in patients with AECOPD was 17% [14, 15]. The probability of developing aspiration pneumonia in COPD is 2.4 times higher than that of the general population [16].

The financial impact of dysphagia on inpatient hospitalization is significant, with costs being 40 ∼ 60% higher compared to those without the condition [17]. This has brought a huge economic burden to individuals. Those with dysphagia tend to have prolonged hospital stays, incur higher bills, and are more likely to require post-discharge medical arrangements [18]. This financial strain can have a cascading effect on an individual’s daily life, leading to increased stress, anxiety, and depression, ultimately diminishing their overall quality of life. Moreover, the long-term effects of anxiety and depression are considerable, further exacerbating the decline in quality of life [19, 20]. Within nursing home settings, COPD stands out as the second most influential factor predicting the occurrence of aspiration pneumonia, which is closely linked to dysphagia [21]. Individuals with dysphagia face an elevated risk of mortality compared to those without the condition [18, 22]. Consequently, the interaction between COPD and dysphagia represents a potential contributing factor to the high mortality rates associated with COPD. Early and accurate identification and assessment of swallowing function in patients with AECOPD is critical.

However, the existing research evidence is insufficient to provide valuable evidence for clinicians to identify and evaluate the swallowing function of AECOPD in the early stage [23,24,25]. This study was designed to screen and evaluate swallowing function in patients with AECOPD by water swallow test (WST) [15], and to screen for relevant swallowing risk factors, and providing reference for clinicians to early evaluate and prevent swallowing risk in AECOPD, as well as develop protective measures, treatment, liquid and nutritional needs.

Materials and methods

Participants

Patients with AECOPD hospitalized at Guangdong Provincial Hospital OF Chinese Medicine were included from June 2022 to April 2023. Diagnostic criteria for AECOPD: Based on the patient’s symptoms, signs, chest X-ray or CT, and Pulmonary function examination, in accordance with the 2023 GOLD guidelines [1].

Inclusion criteria: Age ≥ 40 years old; Stable vital signs; Able to eat orally which was screened by functional oral Intake Scale (FOIS) [26]; Normal language communication skills; Able to cooperate in completing assessments and investigations.

Exclusion criteria: Severe cognitive impairment was assessed by mini-mental state examination (MMSE). (Normal: 27–30; mild cognitive impairment: 21–26; moderate cognitive impairment: 10–20; severe cognitive impairment: 0–9) [27]; Patients with dysphagia due to other categorization of disease, such as stroke, central nervous system disease, head and neck tumors, Alzheimer’s disease, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Ethical approval

Every participant in this study has provided their informed consent, and the research has undergone thorough review by the Medical Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial Hospital OF Chinese Medicine.

Observation and measurement

Observations include gender, age, smoking, underlying diseases, course of disease, use of BIPAP assisted ventilation, Pulmonary function grading (PFG), COPD Assessment Test (CAT) [28, 29], modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) [29,30,31] and hospitalization days. Predict their association with swallowing risk in AECOPD.

Assessment of swallowing function

The WST is useful for the early identification of dysphagia and screening for aspiration [32]. In addition, this screening method is simple to operate, harmless and without additional costs [33]. Therefore, in this study, we applied the WST to evaluate and screen for swallowing risk issues in patients [15]. The WST was used for evaluation as shown in Table 1.

Procedure

The questionnaire survey was conducted face-to-face by attending physicians who received unified training using standard and neutral language, and swallowing function was evaluated with WST on the day of patient admission. Method: Patients were instructed to drink 30 mL of warm water when the sitting position or the head of the bed was raised > 60 º. The researcher observed the process of drinking water for the patient, and recorded whether there was cough, the number of times of drinking water, time consuming.

Grade I: Drinking water once within 5 s without coughing.

Grade II: Drinking water twice or more without choking or coughing.

Grade III: Drinking water at once but with coughing.

Grade IV: Drinking water twice or more times and with coughing.

Grade V: Coughing frequently and cannot drink the water successfully.

Normal: Grade I, less than 5 s; Suspicious: Grade I, more than 5 s or II; Abnormal: grade III ∼ V. According to the WST score, and the included cases were divided into low-risk swallowing group (WST ≤ 1) and high-risk swallowing group (WST ≥ 2).

The questionnaire was filled out anonymously. If the patient is unable to fill it out independently, the investigator will truthfully fill it out on their behalf through question and answer. After completing the questionnaire, it will be retrieved on the spot, invalid questionnaires will be removed, and the questionnaire will be numbered.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R software (version 4.1.2, https://www.r-project.org/). Classified variables are expressed as percentages, while continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile spacing [IQR]). We used Wilcoxon rank sum test, Pearson chi square test, or continuous corrected chi square test to examine inter group differences in baseline characteristics, clinical manifestations, and laboratory data. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Use LASSO regression to quantify the contribution of all potential predictive factors to identify important predictive factors and estimate their impact on swallowing risk without overfitting the data. LASSO regression selects potential risk factors for stepwise regression analysis to determine predictive factors related to final swallowing risk, with a threshold P < 0.05 considered important. Use ‘quality’ for stepwise regression analysis.

Results

Characteristics of the research population

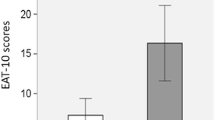

Table 2 displays the demographic details of the participants. According to the WST score, the included cases were divided into low-risk swallowing group (WST ≤ 1) of 50 cases and high-risk swallowing group (WST ≥ 2) of 50 cases. Compared with the low-risk group of swallowing, people at risk of swallowing are older (P < 0.001), have longer hospital stays (P = 0.003), have more acute episodes (P = 0.010), have higher mMRC scores (P < 0.001), higher CAT scores (P = 0.035), are more likely to use BIPAP assisted ventilation (P < 0.001), and have poorer Pulmonary function (Grade IV Pulmonary function) (P = 0.020). From Fig. 1, it can be seen that the importance calculation results of variables in random forests are age, mMRC, CAT score, disease course, BIPAP, number of acute exacerbations, Pulmonary function, etc.

Variable importance sorting. The importance of variables indicates the degree of influence of independent variables on dependent variables. The graph above is a ranking of the importance of variables based on the results of a random forest, arranged from top to bottom. CAT = COPD Assessment Test; mMRC = modified Medical Research Council

LASSO regression analysis

Four potential predictors of swallowing risk were finally identified according to minimum criteria deviation a, minimum absolute contraction and selection operator (LASSO) regression, and stepwise regression, as shown in Table 3; Fig. 2. The regression results showed that the age coefficient was 0.208 and was significant at the level of 1%, which indicated that the probability of swallowing risk increased by 0.208% for each additional year of age, which cutoff value was 74 years, and patients with AECOPD ≥ 74 years had a higher risk of swallowing. The length of hospital stay coefficient was 0.151 and significant at the 5% level, indicating a 0.151% increase in the probability of swallowing risk for each additional day of hospital stay, with a cutoff value 7 days. BIPAP-assisted ventilation coefficient of 1.535 and significant at the 5% level, indicating a 1.535% increased risk of swallowing in patients requiring BIPAP-assisted ventilation. The coefficient for mMRC was 0.790 and significant at the 5% level, indicating a 0.790% increase in the probability of swallowing risk for each 1 grade increase in mMRC. The cutoff value for mMRC was grade 2, and mMRC ≥ 2 had a higher swallowing risk. The Forest plot shows the stepwise regression results for swallowing risk, with all four predictors increasing the incidence of swallowing risk.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis

To determine the discriminatory power of the models (i.e., their ability to distinguish patients with and without swallowing risk), we plotted the ROC curve and computed the area under the curve (AUC). AUC equals 0.909, indicating that the model has good performance. Figure 3.

ROC curve of swallowing risk in AECOPD. ROC curves for different models predicting swallowing risk. Clinical parameters included age, length of hospital stay, use of BIPAP assisted ventilation and mMRC. The area under the ROC curve is the prediction performance of the model, The discrimination was low when the AUC was 0.5, moderate when the AUC was 0.6 to 0.8, and good when the AUC was greater than 0.8; AECOPD = acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ROC = Receiver Operating Characteristic; AUC = Area Under Curve; mMRC = modified Medical Research Council

Calibration of predictive models

Subsequently, a calibration chart was used for visual analysis. In this model, the deviation between the calibration curve and the actual curve is very small, indicating strong model performance. Figure 4.

Calibration diagram of prediction model. The horizontal axis of the calibration chart represents the predicted risk of swallowing, while the vertical axis represents the observed actual risk of swallowing, both ranging from 0 to 1. The red line on the diagonal is the reference line, which refers to the situation where the predicted value equals the actual value. The red line is a curve fitting line, and the gray areas on both sides are 95% CI; CI = confidence interval

Discussion

The act of swallowing is a sophisticated biomechanical process that harmonizes with breathing to safeguard the airway [34]. Yet, in older individuals and those with conditions like COPD, this intricate coordination might not function optimally. When swallowing and breathing are not in sync, it can lead to significant negative outcomes. For instance, individuals experiencing laryngeal penetration are up to four times more prone to developing pneumonia. If pulmonary aspiration takes place, the likelihood of pneumonia increases tenfold [35]. In individuals with COPD, aspiration can happen due to malfunctioning safeguards in the upper airway, decreased harmony between swallowing and breathing, and shifts in breathing patterns brought on by COPD [36]. Although difficulties with swallowing and subsequent aspiration have been acknowledged in COPD for some time, research in this area has been constrained. 56% of COPD patients admitted to the hospital showed positive results in a swallowing screening with WST [9]. Consistent with this, in our study, 50% of patients were at risk of swallowing.

During calm breathing, swallowing tends to occur more frequently during the exhale phase, typically with a moderate-to-low volume of air. This synchronized pattern offers significant biomechanical benefits for both swallowing and safeguarding the airway. It aids in actions such as elevating the larynx, closing the laryngeal vestibule and vocal folds, and opening the cricopharyngeal sphincter [37]. The predominant synchronization between breathing and swallowing involved exhaling-swallowing-exhaling. Grasping the mechanisms that govern this interplay is pivotal in assessing how coordination influences the normal swallowing process in individuals with swallowing difficulties [38].

In normal circumstances when ingesting liquids naturally, there’s a balance struck between the speed and regularity of swallowing, the breathing pattern surrounding swallowing, as well as the rate and volume of respiration. This balance serves the purpose of preventing the risk of pulmonary aspiration [39]. Changes in the coordination of swallowing and breathing could account for the occurrence of pulmonary aspiration and the sensation of breathlessness experienced during swallowing, which is commonly observed in patients with COPD or neurological disorders [40, 41].

Studying the shape changes in rodent swallows through geometric morphometric analysis indicates that the mechanics of swallowing change as animals age. By coupling this with biological tests of age-related adjustments in neuromuscular systems, we can enhance our comprehension of the musculoskeletal issues that underlie swallowing difficulties in the aging process [42].

AGE

As individuals age, certain oropharyngeal swallowing aspects exhibit distinct alterations. In older individuals, there is a noticeable delay in the onset of swallowing and an extended duration of swallowing apnea, particularly notable with larger boluses. Compared to young counterparts, middle-aged and elderly individuals display a reduced occurrence of expiratory-expiratory respiratory patterns. Additionally, the likelihood of piecemeal deglutition is highest in the elderly and lowest in the young. These findings indicate a gradual shift in the phases of oropharyngeal swallowing as one ages [43]. We found that older patients had higher WST scores, while other factors remained unchanged. Age ≥ 74 years old was the cutoff value for swallowing risk. Age may be a risk factor for swallowing risk in patients. The reason may be that with age, the function and mechanism of swallowing change, such as a decrease in swallowing related muscle strength and weakened tongue pressure, which can lead to the occurrence of swallowing abnormalities. This also suggests that elderly patients may be at high risk of swallowing.

mMRC

we found a positive correlation between swallowing risk and mMRC in patients, with a cutoff value level 2. The respiratory rate of patients is accelerated and the respiratory cycle is shortened, which makes it difficult to achieve the breath holding time required for normal swallowing, so that swallowing frequently occurs during the transition period from the inspiratory phase to the expiratory phase or during the inspiratory phase, which is prone to poor coordination between breathing and swallowing, and prone to swallowing risk leading to aspiration.

PFG

Unfortunately, we did not find any further correlation between PFG and swallowing risk. Swallowing problems in stable COPD are related to lower physical abilities, but not to Pulmonary function [7]. A noteworthy inverse relationship exists between AECOPD Pulmonary function and self-reported difficulty in swallowing. However, there isn’t a significant inverse correlation between Pulmonary function and dysphagia identified through clinical screening [9].

BIPAP

Patients who use BIPAP assisted ventilation have an increased risk of swallowing. It may be related to more severe breathing–swallowing disorders in patients who require BIPAP assisted ventilation. However, Continuous positive airway pressure ventilation (CPAP)can reduce the swallowing risk of AECOPD [44, 45]. Patients with COPD demonstrated segmented swallowing, leading to extended durations for water bolus ingestion. Additionally, they tended to take a breath after each swallow. Compared with spontaneous breathing, swallowing efficiency and the breathing–swallowing pattern improve with CPAP, and dyspnoea decreases during swallowing when using CPAP [37]. In addition, compared with spontaneous breathing and BiPAP, CPAP reduces aspiration risk in patients [44].

Hospitalization days

Compared with patients with low swallowing risk, patients with high swallowing risk have longer hospitalization days, with a cutoff value of ≥ 7 days. This may be related to the occurrence of aspiration or insufficient nutrient intake.

Number of episodes and CAT

Finally, in the single factor difference analysis of swallowing risk, the number of episodes and CAT were all related to swallowing risk. However, in the subsequent binary logistic regression analysis, their impact on the risk of swallowing in patients was not statistically significant. This may be because the correlation between variables was not included in the difference analysis. The result of multivariate analysis is the effect of independent and dependent variables after excluding other interfering factors. There is an inseparable correlation between the various factors that affect swallowing risk in patients.

In summary, 50(50%) of the included patients were at risk of swallowing. Age ≥ 74 years old, mMRC ≥ level 2, hospitalization days ≥ 7 days and the use of BIPAP assisted ventilation were important influencing factors for swallowing risk in patients with AECOPD.

Our research has some limitations. To start, it’s important to note that the sample size is limited, potentially introducing selection bias. In the survey, it was found that fewer female patients with AECOPD were included, and this may be related to the limited number of female smokers, which is inconsistent with previous reports; Secondly, instrument evaluation can enhance research.

Conclusion

Patients with AECOPD have a risk of swallowing, which is related to age, mMRC, hospitalization days, and the use of BIPAP assisted ventilation. Age ≥ 74 years old, mMRC ≥ level 2, hospital stay ≥ 7 days, and use of BIPAP assisted ventilation are high-risk factors for swallowing in AECOPD. Early swallowing risk screening, assessment, and intervention should be conducted to prevent aspiration pneumonia, reduce readmission times, and improve quality of life.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AECOPD:

-

Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CAT:

-

COPD Assessment Test

- mMRC:

-

Modified Medical Research Council

- WST:

-

Water swallow test

- NIV:

-

Noninvasive ventilation

- SP:

-

Specificity

- PFG:

-

Pulmonary function grading

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ROC:

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic

- AUC:

-

Area Under Curve

References

Agustí A, Celli BR, Criner GJ, Halpin D, Anzueto A, Barnes P, Bourbeau J, Han MK, Martinez FJ, Montes DOM et al. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2023 Report: GOLD Executive Summary. EUR RESPIR J 2023, 61(4).

Diaz-Guzman E, Mannino DM. Epidemiology and prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. CLIN CHEST MED. 2014;35(1):7–16.

Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLOS MED. 2006;3(11):e442.

Venkatesan P. GOLD COPD report: 2023 update. LANCET RESP MED. 2023;11(1):18.

Meghji J, Mortimer K, Agusti A, Allwood BW, Asher I, Bateman ED, Bissell K, Bolton CE, Bush A, Celli B, et al. Improving lung health in low-income and middle-income countries: from challenges to solutions. Lancet. 2021;397(10277):928–40.

Li W, Gao M, Liu J, Zhang F, Yuan R, Su Q, Wang Y, Wang Y. The prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EXPERT REV RESP MED. 2022;16(5):567–74.

Gonzalez LM, Malinovschi A, Brandén E, Janson C, Ställberg B, Bröms K, Blom JM, Lisspers K, Koyi H. Subjective swallowing symptoms and related risk factors in COPD. ERJ OPEN RES 2019, 5(3).

Gonzalez LM, Blom JM, Jennische M, Koyi H. Prevalence of swallowing dysfunction screened in Swedish cohort of COPD patients. INT J CHRONIC OBSTR. 2017;12:331–7.

Gonzalez LM, Janson C, Blom JM, Jonsson M, Mälberg E, Allansson E, Holm C, Jennische M, Koyi H. Swallowing dysfunction in patients hospitalised due to a COPD exacerbation. ERJ OPEN RES 2021, 7(2).

Yoshimatsu Y, Tobino K, Nagami S, Yagi N, Oku Y. Breathing-swallowing discoordination and inefficiency of an Airway Protective mechanism puts patients at risk of COPD Exacerbation. INT J CHRONIC OBSTR. 2020;15:1689–96.

Cvejic L, Guiney N, Nicholson T, Lau KK, Finlay P, Hamza K, Osadnik C, Leong P, MacDonald M, King PT et al. Aspiration and severe exacerbations in COPD: a prospective study. ERJ OPEN RES 2021, 7(1).

Clayton NA, Carnaby GD, Peters MJ, Ing AJ. Impaired laryngopharyngeal sensitivity in patients with COPD: the association with swallow function. INT J SPEECH-LANG PA. 2014;16(6):615–23.

Cvejic L, Harding R, Churchward T, Turton A, Finlay P, Massey D, Bardin PG, Guy P. Laryngeal penetration and aspiration in individuals with stable COPD. RESPIROLOGY 2011, 16(2):269–275.

Cvejic L, Bardin PG. Swallow and Aspiration in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. AM J RESP CRIT CARE. 2018;198(9):1122–9.

Wang T, Zhao Y, Guo A. Association of swallowing problems with frailty in Chinese hospitalized older patients. INT J NURS SCI. 2020;7(4):408–12.

Nativ-Zeltzer N, Nachalon Y, Kaufman MW, Seeni IC, Bastea S, Aulakh SS, Makkiyah S, Wilson MD, Evangelista L, Kuhn MA, et al. Predictors of Aspiration Pneumonia and Mortality in patients with Dysphagia. LARYNGOSCOPE. 2022;132(6):1172–6.

Allen J, Greene M, Sabido I, Stretton M, Miles A. Economic costs of dysphagia among hospitalized patients. LARYNGOSCOPE. 2020;130(4):974–9.

Patel DA, Krishnaswami S, Steger E, Conover E, Vaezi MF, Ciucci MR, Francis DO. Economic and survival burden of dysphagia among inpatients in the United States. DIS ESOPHAGUS. 2018;31(1):1–7.

Yohannes AM, Willgoss TG, Baldwin RC, Connolly MJ. Depression and anxiety in chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, relevance, clinical implications and management principles. INT J GERIATR PSYCH. 2010;25(12):1209–21.

Andenaes R. Psychological characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review. J PSYCHOSOM RES. 2005;59(6):427–8.

Langmore SE, Skarupski KA, Park PS, Fries BE. Predictors of aspiration pneumonia in nursing home residents. Dysphagia. 2002;17(4):298–307.

Shune SE, Karnell LH, Karnell MP, Van Daele DJ, Funk GF. Association between severity of dysphagia and survival in patients with head and neck cancer. HEAD NECK-J SCI SPEC. 2012;34(6):776–84.

Spronk PE, Spronk L, Lut J, Gnacke E, Mijnes D, van Munster B, Kröner A. Prevalence and characterization of dysphagia in hospitalized patients. NEUROGASTROENT MOTIL. 2020;32(3):e13763.

Prestes D, Bilheri D, Nascimento JR, Righi NC, Baldissera C, Silva A, Mancopes R, Pasqualoto AS. Relationship between dysphagia risk and health status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. CODAS. 2020;32(4):e20190036.

Terada K, Muro S, Ohara T, Kudo M, Ogawa E, Hoshino Y, Hirai T, Niimi A, Chin K, Mishima M. Abnormal swallowing reflex and COPD exacerbations. Chest. 2010;137(2):326–32.

Bengisu S, Demir N, Krespi Y. Effectiveness of Conventional Dysphagia Therapy (CDT), Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation (NMES), and Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) in Acute Post-Stroke Dysphagia: A Comparative Evaluation. DYSPHAGIA 2024, 39(1):77–91.

Paredes-Arturo YV, Flórez-Madroñero AC, Diaz-Velásquez DM, Yarce-Pinzon E, Aguirre-Acevedo DC. Factors influencing living space utilization among older afro-colombian adults. ETHNIC HEALTH. 2024;29(2):267–77.

Almagro P, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Huerta A, González-Segura D, Cosío BG. Impact of comorbidities in COPD clinical control criteria. The CLAVE study. BMC PULM MED. 2024;24(1):6.

Santos E, Pinto TF, Xavier RF, Stelmach R, Carvalho-Pinto RM, Carvalho C. Elastic tape reduces dyspnea and improves health status in the short term in nonobese COPD males: a randomized controlled trial. RESP MED. 2024;221:107459.

Chung C, Lee JW, Lee SW, Jo MW. Clinical efficacy of Mobile App-Based, Self-Directed Pulmonary Rehabilitation for patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: systematic review and Meta-analysis. JMIR MHEALTH UHEALTH. 2024;12:e41753.

Shen H, Xu Y, Zhang Y, Ren L, Chen R. Correlation between diaphragmatic excursion and Exercise Tolerance Improvement following Pulmonary Rehabilitation in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease-Obstructive Sleep Apnea Overlap Syndrome. INT J CHRONIC OBSTR. 2024;19:63–75.

Hey C, Lange BP, Eberle S, Zaretsky Y, Sader R, Stöver T, Wagenblast J. Water swallow screening test for patients after surgery for head and neck cancer: early identification of dysphagia, aspiration and limitations of oral intake. ANTICANCER RES. 2013;33(9):4017–21.

Kuuskoski J, Vanhatalo J, Rekola J, Aaltonen LM, Järvenpää P. The Water Swallow Test and EAT-10 as Screening Tools for Referral to Videofluoroscopy. LARYNGOSCOPE 2023.

Kang YJ, Arafa HM, Yoo JY, Kantarcigil C, Kim JT, Jeong H, Yoo S, Oh S, Kim J, Wu C, et al. Soft skin-interfaced mechano-acoustic sensors for real-time monitoring and patient feedback on respiratory and swallowing biomechanics. NPJ DIGIT MED. 2022;5(1):147.

Pikus L, Levine MS, Yang YX, Rubesin SE, Katzka DA, Laufer I, Gefter WB. Videofluoroscopic studies of swallowing dysfunction and the relative risk of pneumonia. AM J ROENTGENOL. 2003;180(6):1613–6.

Shaker R, Li Q, Ren J, Townsend WF, Dodds WJ, Martin BJ, Kern MK, Rynders A. Coordination of deglutition and phases of respiration: effect of aging, tachypnea, bolus volume, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Physiol. 1992;263(5 Pt 1):G750–5.

Martin-Harris B, Kantarcigil C, Reedy EL, McFarland DH. Cross-System Integration of Respiration and Deglutition: Function, Treatment, and Future Directions. DYSPHAGIA 2022.

Hao N, Sasa A, Kulvanich S, Nakajima Y, Nagoya K, Magara J, Tsujimura T, Inoue M. Coordination of respiration, swallowing, and chewing in healthy young adults. FRONT PHYSIOL. 2021;12:696071.

Ouahchi Y, Ben SN, Mjid M, Hedhli A, Abdelhedi N, Beji M, Toujani S, Verin E. Breathing pattern during sequential swallowing in healthy adult humans. J APPL PHYSIOL. 2019;126(2):487–93.

Lederle A, Hoit JD, Barkmeier-Kraemer J. Effects of sequential swallowing on drive to breathe in young, healthy adults. Dysphagia. 2012;27(2):221–7.

Gross RD, Atwood CJ, Ross SB, Olszewski JW, Eichhorn KA. The coordination of breathing and swallowing in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. AM J RESP CRIT CARE. 2009;179(7):559–65.

Kletzien H, Cullins MJ, Connor NP. Age-related alterations in swallowing biomechanics. EXP GERONTOL. 2019;118:45–50.

Wang CM, Chen JY, Chuang CC, Tseng WC, Wong AM, Pei YC. Aging-related changes in swallowing, and in the coordination of swallowing and respiration determined by novel non-invasive measurement techniques. GERIATR GERONTOL INT. 2015;15(6):736–44.

Hori R, Ishida R, Isaka M, Nakamura T, Oku Y. Effects of noninvasive ventilation on the coordination between breathing and swallowing in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. INT J CHRONIC OBSTR. 2019;14:1485–94.

Terzi N, Normand H, Dumanowski E, Ramakers M, Seguin A, Daubin C, Valette X, Masson R, Sauneuf B, Charbonneau P, et al. Noninvasive ventilation and breathing-swallowing interplay in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease*. CRIT CARE MED. 2014;42(3):565–73.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Hui Yu and Jian Xu for their contributions to this project.

Funding

This study is funded by the Science and Technology Research Project of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine (YN2022MS05).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Y. X. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. D. X. S. was responsible for the concept of the study. S. Y. X., W. F. H2., J. L. Z., W. F. H1 and Y. Z. conducted a questionnaire survey. S. Y. X., and M. Z. D. were responsible for statistical analysis. All authors contributed substantially to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by Medical Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial Hospital OF Chinese Medicine (Number: ZF2022-278-01). Every participants’ informed consent was obtained, with the right to withdraw from the study when they want, and their names and other confdential details were protected. No harm was brought on the participants.

Consent for publication

Consent from participants was obtained to publish the data as anonymous data only.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, S., Zhou, Y., He, W. et al. Study on predictive models for swallowing risk in patients with AECOPD. BMC Pulm Med 24, 95 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-024-02908-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-024-02908-y