Abstract

Background

Clinical characteristics of patients with pulmonary thromboembolism have been described in previous studies. Although very old patients with pulmonary thromboembolism are a special group based on comorbidities and age, they do not receive special attention.

Objective

This study aims to explore the clinical characteristics and mortality predictors among very old patients with pulmonary thromboembolism in a relatively large population.

Design and participants

The study included a total of 7438 patients from a national, multicenter, registry study, the China pUlmonary thromboembolism REgistry Study (CURES). Consecutive patients with acute pulmonary thromboembolism were enrolled and were divided into three groups. Comparisons were performed between these three groups in terms of clinical characteristics, comorbidities and in-hospital prognosis. Mortality predictors were analyzed in very old patients with pulmonary embolism.

Key results

In 7,438 patients with acute pulmonary thromboembolism, 609 patients aged equal to or greater than 80 years (male 354 (58.1%)). There were 2743 patients aged between 65 and 79 years (male 1313 (48%)) and 4095 patients aged younger than 65 years (male 2272 (55.5%)). Patients with advanced age had significantly more comorbidities and worse condition, however, some predisposing factors were more obvious in younger patients with pulmonary thromboembolism. PaO2 < 60 mmHg, eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2, malignancy, anticoagulation as first therapy were mortality predictors for all-cause death in very old patients with pulmonary thromboembolism. The analysis found that younger patients were more likely to have chest pain, hemoptysis (the difference was statistically significant) and dyspnea triad.

Conclusion

In very old population diagnosed with pulmonary thromboembolism, worse laboratory results, atypical symptoms and physical signs were common. Mortality was very high and comorbid conditions were their features compared to younger patients. PaO2 < 60 mmHg, eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2 and malignancy were positive mortality predictors for all-cause death in very old patients with pulmonary thromboembolism while anticoagulation as first therapy was negative mortality predictors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) and PTE is the third most common cause of vascular death after myocardial infarction and stroke. In acute phase it can be fatal and it also can lead to chronic condition [1, 2]. However, the outcome may be improved if the disease is timely diagnosed and properly managed. In recent years, considerable reduction in mortality during hospitalization was obtained over the years, which might be attributed to risk stratification-guided management [3].

Though management and diagnostic strategy improve mortality of PTE, it is still health burden for medical and health services. The incidence of PTE increased with age, this is most pronounced among the old [4]. Patients aged 40 years and older are at increased risk compared with younger patients and the risk approximately doubles every decade. Nowadays life expectancy is getting longer, the old population is a large population worldwide, the rate of venous thromboembolism will increase, thereby increasing the health burden [5,6,7]. The old are not only a large population, but also the main population using medications for chronic disease. Age and comorbidities were already confirmed to be associated with poor outcomes [4]. However, old patients are seldomly recruited in randomized clinical trials due to age, multimorbidity and disabilities [8]. Therefore, evidence-based clinical guidelines do not make recommendations for old people of all ages. Clinicians may treat old patients based on general guidelines and their own experience with uncertainty. There have been several studies focusing on patients with pulmonary embolism over 65 years [9,10,11,12,13,14]. Data on clinical characteristics, management and outcome of PE in very old patients is limited. Thus, this study aims to explore the clinical characteristics and mortality predictors among very old patients with PTE in a relatively large population.

Materials and methods

Patients inclusion

The CURES registry (NCT02943343) involved 100 medical centers across China and this study enrolled consecutive patients aged 18 years and older since 2009. Patients were diagnosed acute PTE with or without DVT through computed tomographic pulmonary angiography, ventilation-perfusion lung scintigraphy, magnetic resonance pulmonary angiography or pulmonary angiography. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by all participating centers’ ethics committees. All recruited patients sighed written informed consent for their participation in the registry. Diagnostic methods were chosen by physicians of the participating centers, and management decisions were determined at the discretion of the physicians and the actual condition of the patients in accordance with the guidelines.

Data collection

We collected patients’ data including demographics, risk factors, medical history, symptoms and signs, physical and laboratory examinations, therapeutic management and clinical outcomes of the disease during hospitalization by designated case report forms and then record all data into the electronic data capture system by researchers in each participating centre. Data quality was monitored by local investigators and members from research organization who responsible for quality control.

Risk stratification and management

Risk stratification for all patients had been calculated by hemodynamic status and sPESI score according to the 2014 ESC/ERS guidelines in our previous study [1, 3]. Primary therapy included anticoagulation, thrombolysis, interventional thrombectomy and surgical embolectomy. Initial anticoagulation therapy referred to when a patient was first given anticoagulant therapy at admission instead of systemic thrombolysis agents, inferior vena cava filter, interventional thrombectomy or surgical embolectomy. We defined condition that when systemic thrombolysis was given prior to any other treatment as initial thrombolysis therapy.

Grouping, study outcomes and definitions

Patients were divided into three groups: very old (≥ 80 years, as stated elsewhere [15]), old (65–79 years), younger (< 65 years). The primary outcome in this study was the composite of death from any cause during hospitalization. Major bleeding was defined as fatal bleeding, and/or a decrease in hemoglobin levels of greater than 20 g L−1 (1.24 mmol L−1) or more, or leading to transfusion of two or more units of whole blood or red cells, or intracranial bleeding or other condition according to the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasias criteria[16]. The outcome events were assessed by a central adjudication committee.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using the SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions) version 26.0. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation or the median (interquartile range) values, and categorical variables were displayed as number (percentage) values. Variables were compared between groups using independent-samples t test, Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test depending on the types of the variables. Univariable logistic regression model was performed to assess the association between relevant factors and all-cause mortality. Variables with a significance level of p < 0.05 were included in the multivariable logistic regression analysis. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were used to demonstrate the associations.

Results

Seven thousand four hundred thirty-eight patients diagnosed as acute PTE were included in the CURES registry from January 2009 to December 2015. In those patients enrolled, 609 patients aged equal to or greater than 80 years (male 354 (58.1%)). There were 2734 patients aged between 65 and 79 years (male 1313 (48%)) and 4095 patients aged younger than 65 years (male 2272(55.5%)) (Table 1).

Patients with advanced age had significantly more comorbidities (including hypertension, coronary heart disease, heart failure, COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), pulmonary infection, pulmonary tuberculosis, interstitial lung disease, cor pulmonale, bronchiectasis, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, neurological diseases, liver and kidney disease, p < 0.05) and some predisposing factors were more common in younger patients with PTE (surgery and trauma in 3 months, immobilization more than 3 days, central venous catheterization, p < 0.05). Younger patients were more often diagnosed as PTE accompanied by DVT.

Patients with advanced age had more worse condition: lower BMI (body mass index), lower platelet count, lower hemoglobin, lower PaO2, lower eGFR, higher cardiac biomarkers, p < 0.05) (Table 1), old patients more often presented with clinical manifestations like cough and sputum. The analysis found that younger patients were more likely to have chest pain, hemoptysis (the difference was statistically significant) and dyspnea triad. Though not significant, there is a tendency for younger patients to be more prone to syncope when VTE occurs. When a physical examination was performed, temperature > 37.3◦C, pulse > 110/min, SBP (systolic blood pressure) < 100 mmHg, respiratory rate > 20/min, P2 increase, positive Homan sigh and gastrocnemius tenderness were more frequent in younger patients. In old and very old patients, signs included cyanosis, moist crackle, wheezing, cardiomegaly, leg edema and jugular venous distention were more common than that in younger patients.

High risk PTE was more common in younger patients, almost twice as often as that in very old patients. The number of patients who received thrombolysis as the initial treatment was 13 (2.2%) in very old patients, 286 (10.7%) in group aged 65-79 years and 607 (15.1%) in younger patients respectively. The main treatment in all three groups was anticoagulation. All cause death increased from 2.3% to 7.4% with age (p < 0.001). There was a trend that the rate of bleeding increased with age but not significant. There was no significant difference in the incidence of major bleeding (Table 2).

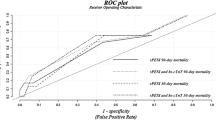

The outcomes of patients at different age period were shown in the Fig. 1. It could be seen that the mortality rate of patients with PTE increased significantly with the increase of age (p < 0.001), while there was no statistical difference in bleeding events and major bleeding events at different age period.

Comparison between survival and death groups in very old patients

The demographic characteristic showed that very old patients with a prognosis of death had lower BMI (21.6 ± 2.8 vs 23.2 ± 3.4, p = 0.002), more comorbid malignancy (7 (15.6%) vs. 36 (6.4%), p = 0.021) and anemia (20 (46.5%) vs. 152 (27.8%), p = 0.009). They had worse laboratory results: PaO2 < 60 mmHg (17 (47.2%) vs 97 (19.5%), p < 0.001), eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2 (23 ( 56.1%) vs 186 ( 34.4%), p = 0.005). when physical examination was compared, very old patients with a prognosis of death showed more conditions such as pulse > 110/min (7 ( 15.9%) vs 35 ( 6.3%),p = 0.016), SBP < 100 mmHg (3 (6.7%) vs 6 (1.6%), p = 0.019), DBP (diastolic blood pressure) < 60 mmHg (6 (13.3%) vs24 (4.3%), p = 0.007) (Table 3).

There were more high risk PTE in very old patients with outcome of death, almost 11 times as often as that in survival patients. The main treatment in two groups was anticoagulation. Major bleeding occurred more often in very old patients with outcome of death (11.5% vs. 1.6%) (Table 4).

In logistic-regression analysis, multiple-comorbidity in very old patients was not an influencing factor for death. Univariate logistic-regression analysis found chronic nephritis, age, malignancy, anemia, PaO2 < 60 mmHg, eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2, pulse ≥ 110 bpm, SBP < 100 mmHg and DBP < 60 mmHg might be influencing factors of death in very old patients. Thus, they were analyzed in multivariate logistic-regression analysis. The results showed that PaO2 < 60 mmHg ( OR 0.216, 95% CI 0.094–0.497, p < 0.001), eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2 (OR 0.361, 95%CI 0.160–0.814, p = 0.014), malignancy (OR 0. 245, 95%CI 0.091–0.658, p = 0.005), anticoagulation as first therapy (OR 3.826, 95%CI 1.511–9.688, p = 0.005) were mortality predictors for all-cause death in very old patients with pulmonary embolism (Table 5).

Discussion

Our study results showed that in those 7,438 patients, 609 patients aged equal to or greater than 80 years (58.1%). As a result of population aging, the number of older patients is increasing, especially patients with PTE which its incidence increases with age. Recommendations for older patients on common cardiovascular diseases in current guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology are missing or scarce, let alone PTE [2, 15]. Guidelines rarely provide advice to older patients mainly because older patients were seldomly recruited in previous clinical trials due to age, multimorbidity and disabilities and thus limited evidence concerning diagnosis and treatment of those older patients was summarized [8].

In this study, older patients had significantly more comorbidities but some predisposing factors for PTE such as surgery, trauma, immobilization, central venous catheterization were more common in younger patients. In addition, PTE accompanied by deep vein thrombosis (DVT) were more often diagnosed in younger patients. Such results remind us that older patients with PTE are more likely to develop “unprovoked” PTE, which was in accordance with previous study (old ≥ 65 years) [9]. Older patients may be less prone to PTE due to deep venous embolism than younger patients. Besides, we also found that old patients had symptoms like cough and sputum more frequent than that in their younger counterpart patients. In contrast, chest pain, hemoptysis and dyspnea triad were less common in very old patients. Another research found patients with PTE aged 80 and older were more likely to show syncope (10% vs 6%) at presentation than those younger than 80 [17]. This number was reversed in our study but it was not statistically significant. In our results, syncope was more frequent in younger (8.2% in very old vs.10.0% in 65–79 years vs.11.1% in younger patients), this was consistent with their high-risk distribution (2.5% high risk in very old vs.4.0% high risk in 65–79 years vs.4.5% high risk in younger patients). Thus, we can conclude that the old patients are less likely to show the typical clinical manifestations of PTE that we have considered in the past, but may often present with symptoms like aggravation of underlying disease, for example, COPD and cardiac insufficiency.

In previous study, population aging and high comorbidity were risk factors for PTE and old patients presented with syncope and dyspnea more frequently than in younger patients [11]. In our age stratified study, though not significant, there is a tendency for younger patients to have syncope and dyspnea when PTE occurs. Very old patients have high comorbidity and less typical symptoms. In recent years, many studies have been conducted to help diagnose PTE properly and have improved guidelines. About the old patients, some scholars have suggested that the application of both a fixed higher D-dimer cutoff (1000 ng/mL) and the age-adjusted threshold would increase the specificity of D-dimer assay for excluding PTE and do not reduce sensitivity [18]. When a physical examination was performed, changes in vital signs were more frequent in younger patients and the very old often present with clinical manifestations that seemed to be related to underlying diseases such as moist crackle, wheezing and so on. Nonspecific manifestations and laboratory results might be erroneously attributed to common diseases or to age itself, thus can delay the diagnosis and even misguide treatment [19]. Nonspecific manifestations and laboratory results widened the spectrum of differential diagnosis of PTE in the older, and high clinical suspicion is needed to prevent delays in diagnosis [20]. All these suggest that it is precisely at this stage of suspicion during diagnosis and management of PTE that older people and younger people have different questions to consider. Given the convenience of the current inspection, someone may add check items to reduce missed diagnosis, but this strategy obviously can’t be promoted among all old patients not only because of the cost, but also because the potential renal toxicity of intravenous contrast and the high incidence of renal dysfunction in the old patients themselves [21,22,23]. Thus, finding a balance between under-suspicion and over-suspicion of PTE is a particularly challenging issue for those very old patients with higher risk of contrast nephropathy.

In our study, age stratified prognosis showed that mortality increased every ten years. All cause death increased from 2.3% to 7.4% with age group (p < 0.001). Beside the impact of age itself on mortality, high comorbidity rate such as changes in cardiac function and renal function due to various diseases and age-related fragility all contribute to poor prognosis of old patients [10, 24]. In clinical practice, in fear of bleeding events, some physicians may mistake advanced age and comorbidity as a contraindication to treatment like anticoagulation and thrombolysis [25]. 15.1% of the younger patients were given thrombolysis as the initial treatment but only 2.2% of the very old patients had thrombolysis as the initial treatment. These practice lead to the higher morbidity and mortality associated with PTE in the old than in younger patients [19]. Indeed, results in our research showed no significant difference in major bleeding incidence between age stratified groups, there was a trend that the rate of bleeding increased with age groups but not significant, which was not consistent with previous study [9]. One reason is that the management of pulmonary embolism has improved in recent years [3, 26]. The participating centers in this study choose appropriate treatment strategy and carry out strict control of indications and contraindications. In addition, anticoagulation was administrated according to age and renal function. In some cases, we aimed for an INR level of 1.8–2.5 in old patients instead of an INR level of 2.0–3.0 to avoid bleeding. In RIETE study, the 3.7% incidence of fatal PE in patients aged ≥ 80 years old outweighed the 0.8% of fatal bleeding [27]. In this study, appropriate therapy also did not increase the incidence of bleeding in very old patients. In earlier study [17], Moutzouris JP et.al published that no difference in short-term mortality was found between octogenarians and their younger counterpart. With appropriate assessment of the condition and appropriate choice of treatment to reduce the risk of bleeding, there seems to be more reason to concern about severity of pulmonary embolism itself in old patients rather than to treat advanced age as a contraindication for fear of bleeding.

In this study, very old patients with a prognosis of death had lower BMI, more malignancy and anemia, worse laboratory results and higher incidence of high-risk PTE. Besides, PAO2 < 60 mmHg, eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2, malignancy and whether anticoagulation as first therapy were mortality predictors for all-cause death in very old patients with PTE. The choice of anticoagulation as first treatment strategy is beneficial to the prognosis of very old patients during hospitalization. In another retrospective cohort study, researchers found that, in emergency department, mortality is high in an old population with a clinically suspected PTE. They suggest that sPESI scoring, even combined with cardiac troponin testing, is not sufficient to predict mortality in old patients [28]. Perhaps more and better larger studies are needed to promote the development of better risk stratification tools for old and very old patients.

Limitations

The main limitation of our study is that we enrolled consecutive patients with confirmed diagnosis of PTE. Those patients who died rapidly in the emergency department with a high suspicion of pulmonary embolism death were not included. Therefore, difference of clinical manifestation and outcome of PTE in real world between younger, old and very old patients was not concluded. Since some results were not consistent with previous study, our results need to be confirmed in larger cohorts. The reason only 2 individuals (4.4%) in the death group received thrombolysis despite 7 individuals (15.6%) being classified as high risk was not recorded in our date. In high-risk patients, patients themselves or relatives may refuse thrombolysis because of fear for bleeding. If the physician assesses the very old patient at a very high risk of bleeding, they may not carry out thrombolysis. Our database failed to record the specific causes. Another limitation is that, in multicenter study, some specific causes of death were not retrievable and no definite conclusions can be drawn on relationship between treatment and mortality.

Conclusion

We conclude that in very old population diagnosed with PTE, worse laboratory results, atypical symptoms and physical sighs were common. Mortality was very high and comorbid conditions were their features compared to younger patients. PaO2 < 60 mmHg, eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2 and malignancy were positive mortality predictors for all-cause death in very old patients with PTE while anticoagulation as first therapy was negative mortality predictors. After reasonable choice of treatment, the incidence of bleeding did not significantly increase with age. The very old patients should receive more attention than the young patients because of their comorbidities and frailty, rather than being excluded from clinical research that influences guidelines, and should not be considered as a contraindication for examination and treatment.

Availability of data and materials

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Abbreviations

- CURES:

-

The China pUlmonary thromboembolism REgistry Study

- PTE:

-

Pulmonary thromboembolism

- VTE:

-

Venous thromboembolism

- DVT:

-

Deep vein thrombosis

- sPESI:

-

Simplified pulmonary embolism severity index

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- IVC:

-

Inferior vena cava

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

- PaO2:

-

Arterial blood gas oxygen partial pressure

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- CTN:

-

Cardiac troponin

References

Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(43):3033–69, 3069a-3069k.

Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J. 2020;41(4):543–603.

Zhai Z, Wang D, Lei J, et al. Trends in risk stratification, in-hospital management and mortality of patients with acute pulmonary embolism: an analysis from the China pUlmonary thromboembolism REgistry Study (CURES). Eur Respir J. 2021;58(4):2002963.

Pauley E, Orgel R, Rossi JS, Strassle PD. Age-stratified national trends in pulmonary embolism admissions. Chest. 2019;156(4):733–42.

Anderson FA Jr, Spencer FA. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 Suppl 1):I9-16.

Stein PD, Hull RD, Kayali F, Ghali WA, Alshab AK, Olson RE. Venous thromboembolism according to age: the impact of an aging population. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(20):2260–5.

Cho SJ, Stout-Delgado HW. Aging and lung disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2020;82:433–59.

Pitkala KH, Strandberg TE. Clinical trials in older people. Age Ageing. 2022;51(5):afab282.

Spencer FA, Gore JM, Lessard D, et al. Venous thromboembolism in the elderly. A community-based perspective. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100(5):780–8.

Ösken A, Yelgeç NS, Şekerci SS, Asarcıklı LD, Dayı ŞÜ, Çam N. Differences in clinical and echocardiographic variables and mortality predictors among older patients with pulmonary embolism. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33(8):2223–30.

Castelli R, Bergamaschini L, Sailis P, Pantaleo G, Porro F. The impact of an aging population on the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: comparison of young and elderly patients. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2009;15(1):65–72.

Minges KE, Bikdeli B, Wang Y, et al. National trends in pulmonary embolism hospitalization rates and outcomes for adults aged ≥65 years in the United States (1999 to 2010). Am J Cardiol. 2015;116(9):1436–42.

Timmons S, Kingston M, Hussain M, Kelly H, Liston R. Pulmonary embolism: differences in presentation between older and younger patients. Age Ageing. 2003;32(6):601–5.

Ayalon-Dangur I, Vega Y, Israel MR, et al. Outcome of elderly patients with venous thromboembolism treated with direct oral anticoagulants-a retrospective cohort study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(23):5673.

Boerlage-van Dijk K, Siegers C, Wouters N, et al. Specific recommendations (or lack thereof) for older patients with cardiovascular disease in the current European Society of Cardiology guidelines: From the Dutch Working Group of Geriatric Cardiology of the Netherlands Society of Cardiology (NVVC) and Special Interest Group Geriatric Cardiology of the Netherlands Society for Clinical Geriatrics (NVKG). Neth Heart J. 2022;30(12):541–5.

Schulman S, Angerås U, Bergqvist D, Eriksson B, Lassen MR, Fisher W. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(1):202–4.

Moutzouris JP, Chow V, Yong AS, et al. Acute pulmonary embolism in individuals aged 80 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(10):2004–6.

Polo Friz H, Pasciuti L, Meloni DF, et al. A higher d-dimer threshold safely rules-out pulmonary embolism in very elderly emergency department patients. Thromb Res. 2014;133(3):380–3.

Berman AR, Arnsten JH. Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary embolism in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 2003;19(1):157–75, viii.

Monreal M, López-Jiménez L. Pulmonary embolism in patients over 90 years of age. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16(5):432–6.

Meguid El Nahas A, Bello AK. Chronic kidney disease: the global challenge. Lancet. 2005;365(9456):331–40.

Mehran R, Aymong ED, Nikolsky E, et al. A simple risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention: development and initial validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(7):1393–9.

Jacobs LG, Billett HH. Office management of deep venous thrombosis in the elderly. Am J Med. 2009;122(10):904–6.

Robert-Ebadi H, Righini M. Diagnosis and management of pulmonary embolism in the elderly. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(4):343–9.

Stein PD, Matta F. Treatment of unstable pulmonary embolism in the elderly and those with comorbid conditions. Am J Med. 2013;126(4):304–10.

Bikdeli B, Wang Y, Jimenez D, et al. Pulmonary embolism hospitalization, readmission, and mortality rates in US older adults, 1999–2015. JAMA. 2019;322(6):574–6.

López-Jiménez L, Montero M, González-Fajardo JA, et al. Venous thromboembolism in very elderly patients: findings from a prospective registry (RIETE). Haematologica. 2006;91(8):1046–51.

Polo Friz H, Molteni M, Del Sorbo D, et al. Mortality at 30 and 90 days in elderly patients with pulmonary embolism: a retrospective cohort study. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10(4):431–6.

Acknowledgements

We thank the China pUlmonary thromboembolism REgistry Study (CURES) Group for all contributions.

CONSORTIUM NAME:

The China Pulmonary Thromboembolism Registry Study (CURES) investigators:

Yuanhua Yang2, Jifeng Li2, Zhenguo Zhai3, Wanmu Xie3, Jun Wan3, Baomin Fang5, Xiaomao Xu5, He Yang5, Qun Yi7, Lan Wang7, Haixia Zhou7, Maoyun Wang7, Hong Chen8, Xiaohui Wang8, Zhihong Liu10, Qin Luo10, Juhong Shi13, Junping Fan13, Zhonghe Zhang16, Yingqun Ji16, Jun An16, Mian Zeng19, Xia Li19, Ling Zhu20, Yi Liu20, Kejing Ying21, Guofeng Ma21, Chao Yan21, Lixia Dong22, Wei Zhou22, Chong Bai23, Wei Zhang23, Liangxing Wang24, Yupeng Xie24, Xiaoying Huang24, Chen Qiu25, Yazhen Li25, Yingyun Fu25, Shengguo Liu25, Shengqing Li26, Jian Zhang26, Xinpeng Han26, Qixia Xu27, Xiaoqing Li27, Yingying Pang27, Beilei Gong27, Ping Huang28, Yanwei Chen28, Jiming Chen28, Guochao Shi29, Yongjie Ding29, Zhaozhong Cheng30, Li Tong30, Zhuang Ma31, Lei Liu31, Luning Jiang32, Zhijun Liang32, Chaosheng Deng33, Minxia Yang33, Dawen Wu33, Shudong Zhang34, Lijun Kang34, Hong Chen35, Fangfei Yu35, Xuewei Chen35, Dan Han36, Shasha Shen36, Guohua Sun37, Yutao Hou37, Baoliang Liu37, Xiaohong Fan38, Wei Zhang38, Ping Zhang39, Ruhong Xu39, Zaiyi Wang40, Cunzi Yan40, Chunxiao Yu41, Zhenfang Lu41, Jing Hua41, Zhenyang Xu42, Hongxia Zhang42, Jinxiang Wang42, Xiaohong Yang43, Ying Chen43, Yongjun Tang44, Wei Yang44, Nuofu Zhang45, Linli Duan45, Simin Qing45, Chunli Liu45, Lian Jiang46, Hongda Zhao46, Chengying Liu46, Yadong Yuan47, Xiaowei Gong47, Xinhong Zhang48, Chunyang Zhang48, Shuyue Xia49, Hui Jia49, Yunxia Liu49, Dongmei Zhang50, Yuntian Ma50, Lu Guo51, Jing Zhang51, Lina Han52, Xiaomin Bai52, Guoru Yang53, Guohua Yu53, Ruian Yang54, Jingyuan Fan54, Aizhen Zhang55, Rui Jiang55, Xueshuang Li55, Yuzhi Wu55, Jun Han55, Jingping Yang56, Xiyuan Xu56, Baoying Bu56, Chaobo Cui57, Ning Wang57, Yonghai Zhang59, Jie Duo59, Yajun Tuo59, Yipeng Ding58, Heping Xu58, Dingwei Sun58, Yonghai Zhang59, Jie Duo59, Yajun Tuo59, Xiangyan Zhang60, Weijia Liu60, Hongyang Wang61, Yuan Wang61, Aishuang Fu61, Songping Huang62, Qinghua Xu62, Wenshu Chai63, Jing Li63, Yanping Ye64, Wei Hu64, Jin Chen64, Bo Liu65, Lijun Suo65, Changcheng Guo66, Ping Wang66, Jinming Liu67, Qinhua Zhao67, Qin Luo68, Le Kang68, Jianying Xu69, Lifen Zhao69, Mengyu Cheng69, Wei Duan69, Qi Wu70, Li Li70, Ping Wang71, Xiuqing He71, Yueyue Li71, Gang Chen72, Yunxia Zhao72, Zixiao Liu72, Guoguang Xia73, Tianshui Li73, Nan Chen73, Xiaoyang Liu73, Tao Bian74, Yan Wu74, Huiqin Yang75, Xiaoli Tang75, Yiwen Zhang76, Faguang Jin77, Ning Wang77, Yanli Chen77, Yanyan Li77, Jing Li78, Miaochan Lao78, Shengqing Li79, Liang Dong79, Guangfa Zhu80, Wenmei Zhang80, Liangan Chen81, Zhixin Liang81, Liping Cui82, Cenfeng Xia82, Jin Zhang82, Peng Zhang82, Lianxiang Guo83, Sha Niu83, Sichong Yu83, Guangjie Liu84, Xinmao Wang84, Yanhua Lv85, Zhenyu Liang85, Shaoxi Cai85, Shuang Yang85, Xinyi Zhang86, Jiulong Kuang86, Yanyan Ding87, Yongxiang Zhang87, Xuejun Guo88, Yanmin Wang88, Jialie Wang89, Ruimin Hu89, Lin Ma90, Yuan Gao91, Rui Zheng91, Zhihong Shi92, Hong Li92, Yingqi Zhang93, Guanli Su93, Zhiqiang Qin94, Guirong Chen94, Xisheng Chen95, Zhiwei Niu95, Jinjun Jiang96, Shujing Chen96, Tiantuo Zhang97, Hongtao Li97, Jiaxin Zhu97, Yuqi Zhou97, Yinlou Yang98, Jiangtao Cheng98, Jie Sun99, Yanwen Jiang99, Jianhua Liu100, Yujun Wang100, Ju Yin101, Lanqin Chen101, Min Yang102, Ping Jiang102, Hongbo Liu102, Guohua Zhen103, Kan Zhang103, Yixin Wan104, and Hongyan Tao104.

19.The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University;

20.Shandong Provincial Hospital;

21.Sir Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine;

22.Tianjin Medical University General Hospital;

23.Changhai Hospital;

24.The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University;

25.Shenzhen People’s Hospital;

26.Xijing Hospital;

27.The First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College;

28.Shenzhen Sixth People’s Hospital [Nanshan Hospital] Huazhong University of Science and Technology Union Shenzhen Hospital);

29.Ruijin Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine;

30.The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University;

31.The General Hospital of Shenyang Military;

32.Affiliated Hospital of Jining Medical University;

33.The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University;

34.Yantaishan Hospital;

35.The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University;

36.The First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University;

37.Zibo First Hospital;

38.Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital;

39.Dongguan People’s Hospital;

40.The First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University;

41.Beijing Jingmei Group General Hospital;

42.Beijing Luhe Hospital, Capital Medical University;

43.People’s Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region;

44.Xiangya Hospital Central South University;

45.The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University [Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Health];

46.Jiangyin People’s Hospital;

47.The Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University;

48.The Sixth Medical Center of People’s Liberation Army General Hospital;

49.Central Hospital Affiliated to Shenyang Medical College;

50.Tianjin Ninghe District Hospital;

51.Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences & Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital;

52.Handan First Hospital;

53.Weifang Respiratory Disease Hospital;

54.The First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province;

55.Shanxi Provincial People’s Hospital;

56.The Third Affiliated Hospital of Inner Mongolia Medical University;

57.Harrison International Peace Hospital;

58.Hainan General Hospital;

59.Qinghai Provincial People’s Hospital;

60.Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital;

61.North China University of Science and Technology Affiliated Hospital;

62.Quanzhou First Hospital;

63.The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou Medical University;

64.Fu Xing Hospital, Capital Medical University;

65.Linzi District People’s Hospital;

66.Taiyuan Central Hospital;

67.Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital;

68.The Third Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University;

69.Shanxi Academy of Medical Sciences, Shanxi Dayi Hospital;

70.Tianjin Haihe Hospital;

71.The 306th Hospital of People’s Liberation Army;

(72.The Third Hospital of Hebei Medical University;

73.Beijing Jishuitan Hospital;

74.Wuxi People’s Hospital;

75.Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Hospital of Traditional Chinese medicine;

76.Anhui Chest Hospital;

77.Tangdu Hospital;

78.Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences, Guangdong General Hospital;

79.Shanghai Huashan Hospital;

80.Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University;

81.Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital (Medical School of Chinese People’s Liberation Army;

82.General Hospital of Ningxia Medical University;

83.Jiaozuo Second People’s Hospital;

84.Beijing Tongren Hospitall, Capital Medical University;

85.Nanfang Hospital;

86.The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University;

87.People’s Hospital of Beijing Daxing District;

(88.Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine;

89.Inner Mongolia People’s Hospital;

90.The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University;

91.Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University;

92.The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University;

93.The First Hospital of Hebei Medical University;

94.The People’s Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region;

95.The Hospital of Shunyi District Beijing;

96.Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University;

97.The Third Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University;

98.Yue Bei People’s Hospital;

99.Beijing Shijitan Hospitall, Capital Medical University;

100.Beijing Huairou Hospital of University of Chinese Academy of Sciences;

101.Beijing Children’s Hospital, Capital Medical University;

102.Tianjin First Central Hospital;

103.Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology;

104.Lanzhou University Second Hospital.

Funding

The study was funded by the China Key Research Projects of the 12th National Five-Year Development Plan (number 2011BA11B17), the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (number 2018-I2M-1–003), the National Key R&D Program of China (number 2016YFC0905600, 2016YFC0901104), the National Key Research and Development Program (2023YFC2507200), the National Nature Science Foundation of China (81900047, 62206187), Beijing Research Ward Demonstration Construction Project (No. BCRW202110), and the Financial Budgeting Project of Beijing Institute of Respiratory Medicine (Ysbz2023003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Y.H. Yang and Z.G. Zhai conceived the study. X. Zhou, X.M. Xu, Y.Q. Ji, Q. Yi, H. Chen, X.Y. Hu, Z.H. Liu, Y.M. Mao, J. Zhang, J.H. Shi, Q. Gao, X.C. Tao, W.M. Xie, J. Wan, Y.X. Zhang, S. Zhang, K.Y. Zhen, Z.H. Zhang and B.M. Fang collected data. X. Zhou analysed and interpreted data and drafted the manuscript. Y.H. Yang revised the manuscript. Z.G. Zhai and C. Wang obtained funding and supervised the study. Y.H. Yang and Z.G. Zhai contributed equally as the lead corresponding authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee in China-Japan Friendship Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Consent for publications

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplement. Echocardiography in very old patients with PTE.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, X., Yang, Y., Zhai, Z. et al. Clinical characteristics and mortality predictors among very old patients with pulmonary thromboembolism: a multicenter study report. BMC Pulm Med 24, 26 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-023-02824-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-023-02824-7