Abstract

Background

Asthma is a common airways disease with significant morbidity and mortality in all ages. Studies of pediatric asthma control and its determinants yielded variable results across settings. However, there is paucity of data on asthma control and its factors in Ethiopian children. We aimed to assess the level of asthma control and the related factors in children attending pediatric respiratory clinics at three tertiary hospitals in Addis Ababa.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study from March 1 to August 30, 2020 using standardized questionnaires and review of patient’s charts. Data was analyzed using SPSS software for window version 26.

Results

A total of 105 children (56.2% male) were included in the study. The mean age (± SD) and age at Asthma diagnosis (± SD) were 6 (± 3.3) and 4 (± 2.8) respectively. Uncontrolled asthma was present in 33 (31%) of children. Comorbidities (Atopic dermatitis and allergic Rhinitis (AOR = 4.56; 95% CI 1.1–18.70; P = 0.035), poor adherence to controller medications (AOR = 3.23; 95% CI 1.20–10.20; P = 0.045), inappropriate inhaler technique (AOR = 3.48; 95% CI 1.18–10.3; P = 0.024), and lack of specialized care (AOR = 4.72; 95% CI 1.13–19.80; P = 0.034) were significantly associated with suboptimal asthma control.

Conclusion

One-third of children attending pediatric respiratory clinics in Addis Ababa had uncontrolled Asthma. Treatment of comorbidities, training of appropriate inhaler techniques, optimal adherence to controllers, and proper organization of clinics should be emphasized to improve asthma control among children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Asthma is among the most common respiratory diseases with significant morbidity and mortality across all ages [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates 339 million people suffer from asthma worldwide [1, 2]. Asthma is among the most common pediatric diseases in African children with a prevalence range of 9% in Ethiopia to 20% in South Africa [3]. A recent review showed that overall prevalence of asthma was 13.9% (95% CI 9.6–18.3) in African children younger than 15 years [4]. In 2015, Asthma was estimated to cause 14.7 deaths per 100,000 individuals in Ethiopia, ranking 17th among the top 20 causes of mortality [5].

The major goal of asthma management is to achieve control of the disease and to improve the quality of life of affected children and their families, avoid school absenteeism, increase productivity, and prevent the need for emergency care and hospitalizations [6,7,8,9]. However, most patients, especially children, do not receive optimal asthma management secondary to poor inhaler technique and other complex factors [10, 11]. Multiple previous studies have documented variable but important results of pediatric asthma control and its factors in different settings. Prevalence of poorly controlled asthma in these pediatric studies varied from as low as 16% to as high as 84% [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Major factors related to poor asthma control, as documented in previous studies include, but not limited to, respiratory tract infections, lack of shared decision-making, inadequate asthma education, poor drug adherence, asthma severity, presence of comorbidities and other sociodemographic factors, previous asthma exacerbation, and type of controller medication [10, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

Asthma control and its determinants vary from practice setting as environmental, socio-demographic, medication adherence and availability, and household factors differ significantly across settings [13, 14, 29]. Previous work in Ethiopia, showed that in a tertiary hospital in Addis Ababa a third of adult asthmatics had poor asthma control [30]. However, there are limited data on childhood asthma control from low-income countries including Ethiopia. Thus, this study aimed to assess the level of and factors related to asthma control in children attending pediatric respiratory clinics in three tertiary centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Knowledge of level of asthma control and related factors will help to develop strategies to improve asthma care and decrease asthma morbidity and mortality in Ethiopia and potentially other low-income countries.

In this study, we defined bronchial asthma as physician-diagnosed asthma consistent with asthma symptoms and signs (episodic wheezing, cough, shortness of breath, chest tightness), and airway reversibility evidenced by response to short acting beta agonists and/or spirometry (when available) in children older than 5 years of age. Preschool asthma was defined as frequent (≥ 8 days/month) asthma-like symptoms or recurrent (≥ 2) exacerbations (episodes with asthma-like signs) in children 1–5 years old as defined by the Canadian pediatrics society and response to asthma medications [31].

Methods and materials

Study design and settings

The study was conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The Ethiopian health system follows a primary, secondary and tertiary level of referrals, and patients mainly pay out of pocket for health care services including drugs while government pays for those who didn’t afford to pay.

A hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted from March 1 to August 30, 2020 in 3 tertiary teaching hospitals (Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital (TASH), St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College (SPHMMC), and Yekatit 12 Hospital Medical College (Yekatit 12)) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The hospitals were selected as they have respiratory clinics providing clinical care for children with asthma.

TASH is the largest university hospital in the country. The pediatric respiratory clinic at TASH is open twice weekly and is led by a pediatric pulmonologist and consists of a team of clinicians including a pediatric pulmonologist, pediatric pulmonology fellow, senior pediatric residents rotating to the clinic, and nursing staff. An average of 60 patients with respiratory diseases are evaluated in the pulmonary clinic per month.

SPHMMC is the second largest hospital in Ethiopia. There is a once weekly follow up at the pediatric respiratory clinic for pediatric pulmonary diseases including asthma. Skin allergy test and spirometry services are available regularly in SPHMMC while the other two hospitals lack these services. The respiratory clinic is led by a pediatric pulmonologist and consists of a team of clinicians including a pediatric pulmonology fellow, and senior pediatric residents in their pulmonology rotation.

Yekatit 12 is a teaching hospital in Addis Ababa and its pediatric respiratory clinic is open once weekly providing service by a team consisting of a pediatrician, residents, and nursing staff but no pediatric pulmonologist. The asthma care is mostly handled by residents with inconsistent availability of pediatricians and care less structured compared to the other two centers where the clinics are organized and led by pediatric pulmonologists.

Participants and sampling method

Children 1–14 years old with physician‑diagnosed asthma, who visited the 3 pediatric respiratory clinics, and are on controller therapy for a minimum of 3 months were included. Patients with cardiorespiratory comorbidities and those with uncertain diagnoses were excluded despite being on controller medications.

Sample size was calculated using single population proportion formula with a 95% confidence interval, 5% margin of error and prevalence of 18% from a previous Nigerian study. After correction for a finite population, the final sample size was 107. However, only 105 (98% of the calculated sample size) patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Among them, 39 (37%) children were from TASH, 42 (40%) from SPHMMC whereas 24 (23%) were from Yekatit 12 hospital.

Data collection and measurements

Trained general practitioners and pediatric residents collected the data by interview of the child and /care-giver using a pre-tested standardized questionnaires and check lists. Asthma control was evaluated by using standardized age appropriate tools; Test for Respiratory and Asthma Control in Kids (TRACK) for < 5 years [32], Childhood-Asthma control test (C-ACT) for 5–< 12 years [33], and Asthma Control Test (ACT) for ≥ 12 years [34]. Asthma Control Test (ACT) is a 5-point questionnaire used to assess asthma control in children 12–14 years of age.

The Childhood Asthma Control Test (C-ACT) is a 7-point questionnaire used to assess asthma control in children 6–12 years of age, while Test for Respiratory and Asthma Control in Kids (TRACK) is a 5-point questionnaire used to assess asthma control for children under five years old. Uncontrolled asthma was defined based on a total C-ACT or ACT score ≤ 19 or TRACK score ≤ 80 as appropriate for age and drug adherence was considered optimal if medication adherence is greater than 80% as determined by medications adherence response scale for asthma (MARS-A score) [35, 36].

Data processing and analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS version 26 after cleaning before analysis. Descriptive statistics like frequencies, mean, and standard deviations (SDs) were used to summarize the independent variables. Chi- square test with bivariate analysis were performed to evaluate the association between dependent and independent variables. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were estimated to see strength of the associations and p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered to be of statistical significance. Missing values were handled by subgroup analysis.

Results

Sociodemographic character of study subjects

The study included 105 children with asthma of which 59 (56.2%) were males. Mean (± SD) current age and age at asthma diagnosis (± SD) were 6 (± 3.3) and 4 (± 2.8) years respectively. More than 71% of children were less than 12 years of age (Table 1). A third of caregivers were housewives (33%) and educated either to primary (6.7%) or secondary (45.7%) level. Most (83%) children were from Addis Ababa. Family history of asthma was present in only 21 (20%) children with a 12% rate of parental asthma history (Table 2).

Asthma severity, control and related factors

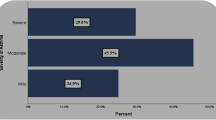

While the overall level of asthma control in our study was 69%, there was a difference between the 3 hospitals with a rate of 79% in SPHMMC, 72% in TASH, and 46% in Yekatit 12 Hospital. There was no association between child’s gender, age, family size, gestational age, type of controller medication, caregivers’ level of education and level of asthma control in the child (Tables 3, 4). Most children (60 (57%) had mild persistent asthma followed by moderate persistent asthma in 39 (37%) and most were on GINA step 2 management (Table 5). Pertaining to objective diagnosis of asthma, only 20 (19%) children had spirometry supported diagnosis of asthma because of age limitation for most children, and test unavailability for some of them.

Comorbid conditions and triggers related to asthma control

Common comorbidities were atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis documented in 42.8% of children. Specific trigger factors for asthma exacerbation and control were identified in 86 (83%) children. The most common triggers for exacerbation were combinations of upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) and Cold weather (55%), URTI and cold weather with dust (26.4%) (Table 2). Most of the children had been hospitalized for asthma exacerbation at least once in the past with 72% hospitalized twice or more for asthma exacerbations (Table 2).

Children with both allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis were more likely to have uncontrolled asthma (AOR = 4.56; 95% CI 1.11–18.70; P = 0.035). However, there was no significant association between triggering factors, previous asthma related admissions, household or tobacco smoke exposures and asthma control. Likewise, family history of asthma and type of fuel used for cooking were not associated with the level of asthma control (Table 2).

Less than 50% of households used clean fuel for cooking; the rest used electricity with unclean fuel (kerosene and firewood) for cooking (55%). Only 2 (1.9%) children were exposed to cigarettes smoke at home.

Drug adherence, inhaler technique, and place of care

Two-third of patients were adherent to their medications, and most of them had controlled asthma (79.4%). The reasons for non-adherence were forgetting to give/take controllers, not knowing how much to give/take, and inadequate prescriptions prior to the next appointment. Inhaler technique was inappropriate in 45 (55%) of children. Beclomethasone was the most commonly used controller in 75 (71%) children followed by Montelukast in 23 (22%). The rest were stepped-down and stopped their controllers because their asthma was well controlled for an adequate time. No patient was followed with written asthma action plan.

Children who were not adherent to medications were 3 times more likely to have uncontrolled Asthma (AOR = 3.23; 95% CI 1.2–10.2; P = 0.045). Likewise, children who had poor inhaler techniques were 3.5 times more likely to have uncontrolled asthma (AOR = 3.48; 95% CI 1.19–10.3; P = 0.024). Asthma control was significantly lower in children from Yekatit-12 hospital (AOR = 4.723; 95% CI 1.125–19.818; P = 0.034). However, there was no association between asthma control and the type of controller used.

Factors associated with uncontrolled asthma

A number of independent predictors of asthma control were found on multivariate analysis (Table 4). The presence of comorbid conditions (atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis), poor inhaler technique, poor adherence to controller drugs, and the specific health care facility independently predicted uncontrolled asthma among the study participants.

Discussion

Our study assessed the level of asthma control and related factors in children attending pediatric respiratory clinics at three tertiary hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Our study demonstrated that every 1 in 3 asthmatic children had an uncontrolled asthma. As current asthma management primarily aims optimal asthma control, it is critical to understand the burden and predictors of uncontrolled asthma in children [6, 7].

Our rate of uncontrolled asthma was lower compared to reports from USA (46%), and Saudi Arabia (59–84%) [19, 24, 26]. This may be due to differences in environmental factors [12, 13, 15] as well as sociodemographic and practice factors including better parental understanding, health seeking and reporting culture from parents and children in middle- and high-income settings [14]. Additionally, the use of different assessment tools, inclusion of different age groups and disease severity may lead to discrepancies of asthma control results. On the contrary, our study showed lower asthma control compared to a single center Nigerian study (18%) [23]. It is possible that at least some of our children are undertreated for their asthma contributing to our poor asthma control. On the other hand, the difference may also be related to the multicenter nature of our study with very low asthma control in one of our centers (Yekatit 12) with uncontrolled asthma of only 21% in a different center (SPHMMC), comparable to the Nigerian study. Additionally, limited follow up of patients with controlled asthma at follow up clinics due to the COVID-19 might have contributed to higher rate of uncontrolled asthma in our children. The other possible reason might be shortage and irregular availability of controller medications especially beclomethasone in the preceding 2 years of the study.

Similar to our work, previous studies reported comorbid allergic conditions to affect asthma control significantly [21, 24, 26]. Saudi Arabian [17] and Australian [21] studies also documented poor drug adherence and inappropriate inhaler techniques to significantly increase uncontrolled Asthma in children.

We observed that the presence of both allergic rhinitis and dermatitis predicted asthma control but neither of them do separately. While presence of allergy may not consistently predict asthma control [37, 38], asthma with both allergic rhinitis and dermatitis (‘atopic march’) marks a special group of children with different genetic and immunologic state possibly contributing to variable severity and asthma control [37, 39]. However, our result should be interpreted with caution as the small sample size and under reporting of allergic rhinitis and dermatitis might have affected our result.

Children followed at Yekatit 12 had lower asthma control compared to the other two centers. This may be related to differences in care providers/physicians and alternative structuring of the clinic compared to the other two centers. A previous study documented better rate of asthma control cared by a specialist (26% uncontrolled) compared to non-specialists (49% uncontrolled) [40].

The type of controller medication, previous asthma exacerbation, and caregivers’ level of education were documented to affect asthma control in previous studies [20, 26, 27], but were not found to be significant in our study. However, our result should be interpreted cautiously as our sample size and similarity of educational and sociodemographic status in controlled and uncontrolled asthmatics may affect the result.

Additionally, contrary to some previous studies [22,23,24,25], asthma severity, rural/urban residence, and family income were not found to affect asthma control in our children. However, we acknowledge that our result has limited generalizability for children from rural area and asthmatics with comorbidities other than allergic rhinitis and dermatitis.

Despite the multicenter nature, our study is limited by relatively small sample size due to the COVID-19 pandemic overlapping with our study period. Similarly, our level of Asthma control might be affected by selection bias as more children with poor asthma control are likely to be available while mild and controlled asthma cases may not attend the follow-up clinics during such unprecedented period. Additionally, few patients were followed up only through phone calls and were not attending the clinics. Additionally, our asthma diagnosis was supplemented by spirometry only in a fifth of children, and the higher proportion of preschool asthmatics puts our asthma diagnosis less precise despite our pragmatic approach as used in larger studies. As a result of this the generalizability of our work may be limited.

In conclusion, one-third of children under follow up in public pediatric centers in Addis Ababa had uncontrolled asthma. Comorbidities (allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis), poor adherence to controllers, facility of care, and inappropriate inhaler techniques are important predictors of uncontrolled Asthma. Treatment of comorbidities, proper education and training of inhaler technique and controller adherence, and organizing respiratory clinics preferably with dedicated pediatricians/pulmonologist when available should be emphasized to optimize the main goal of optimal asthma care in Ethiopia.

Availability of data and materials

Data is available with the authors for review based on request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

Asthma Control Test

- C-ACT:

-

Childhood Asthma Control Test

- COVID-19:

-

SARS-Cov-2 caused Corona Virus disease

- DALY:

-

Disability adjusted life years

- GINA:

-

Global initiative for asthma

- ICS:

-

Inhaled corticosteroid

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- ISAAC:

-

International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Children

- MARS-A:

-

Medication adherence response scale for Asthma

- OCS:

-

Oral Corticosteroids

- OPD:

-

Out Patient Department

- RCT:

-

Randomized control trial

- SABA:

-

Short Acting Beta Agonists

- SPHMMC:

-

St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium College

- TASH:

-

Tikur Anbesa Specialized Hospital

- TRACK:

-

Test for Respiratory and Asthma Control in Kids

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

The Global Asthma Report 2018. Auckland, New Zealand: Global Asthma Network, 2018. www.globalastmanetwork.org.

James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, Abbastabar H, Abd-Allah F, Abdela J, Abdelalim A, Abdollahpour I. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2019;392(10151):1789–858.

ISSAC Steering Committee. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: the International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood (ISAAC). Eur Respir J. 1998;12:315–35.

Adeloye D, Chan KY, Rudan I, Campbell H. An estimate of asthma prevalence in Africa: a systematic analysis. Croat Med J. 2013;54(6):519–31. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2013.54.519.

Misganaw A, Haregu TN, Deribe K, et al. National mortality burden due to communicable non-coomunicable and other diseases in Ethiopia, 190–2015: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Popul Health Metrics. 2017;15:1–17.

Pavord ID, Breasley R, Agusti A, et al. After Asthma: redefining airways diseases. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):350–400.

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2020. www.ginasthma.org.

Dean BB, Calimlim BM, Kindermann SL, Khandker RK, Tinkelman D. The impact of uncontrolled asthma on absenteeism and health-related quality of life. J Asthma. 2009;46(9):861–6.

Williams SA, Wagner S, Kannan H, Bolge SC. The association betwwen asthma control and health care utilization, work productivity loss and health-related quality of life. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(7):780–5.

Carolin MA, Paul JB, Tina LC, Megan MT. Concordance among children, care givers and clinicians on barriesr to controller medication use. J Asthma. 2018;55(12):1352–61.

Pederson S, Frost L, Arnfred T. Errors in inhalation techniques and efficiency in inhaler use in asthmatic children. Allergy. 1986;41(2):118–24.

Bloomberg GR, Banister C, Sterkel R, Epstein J, Bruns J, Swerczek L, Wells S, Yan Y, Garbutt JM. Socioeconomic, family, and pediatric practice factors that affect level of asthma control. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):829–35.

Chen E, Bloomberg GR, Fisher EB Jr, Strunk RC. Predictors of repeat hospitalizations in children with asthma: the role of psychosocial and socioenvironmental factors. Health Psychol. 2003;22(1):12–8.

Dick S, Doust E, Cowie H, Ayres JG, Turner S. Associations between environmental exposures and asthma control and exacerbations in young children: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2014;2:1–8.

van Dellen QM, Stronks K, Bindels PJ, Ory FG, Bruil J, van Aalderen WM, PEACE Study Group. Predictors of asthma control in children from different ethnic origins living in Amsterdam. Respir Med. 2007;101(4):779–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2006.08.002.

Gandhi PK, Kenzik KM, Thompson LA, DeWalt DA, Revicki DA, Shenkman EA, Huang IC. Exploring factors influencing asthma control and asthma-specific health-related quality of life among children. Respir Res. 2013;14(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-14-26.

Al-Muhsen S, Horanieh N, Dulgom S, Aseri ZA, Vazquez-Tello A, Halwani R, Al-Jahdali H. Poor asthma education and medication compliance are associated with increased emergency department visits by asthmatic children. Ann Thorac Med. 2015;10(2):123–31. https://doi.org/10.4103/1817-1737.150735.

Garba BI, Ballot DE, White DA. Home circumstances and asthma control in johannesburg children. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;27(3):182.

Banjari M, Kano Y, Almadi S, Basakran A, Al-Hindi M, Alahmadi T. The the relation between asthma control and quality of life in chidren. Int J Pediatr. 2018;6:1–6.

National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5 Suppl):S94-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043.

Burgess S, Sly P, Devadason S. Adherence with Preventive medication in Childhood Asthma. Pulm Med. 2011;2011:973849.

Papwijitsil R, Pacharn P, Areegarnlert N, Veskitkul J, Visitsunthorn N, Vichyanond P, Jirapongsananuruk O. Risk factors associated with poor controlled pediatric asthma in a university hospital. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2013;31(3):253–7.

Kuti BP, Omole KO, Kuti DK. Factors associated with childhood asthma control in a resource poor setting. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2017;6(2):222–30.

BinSaeed AA, Torchyan AA, Alsadhan AA, Almidani GM, Alsubaie AA, Aldakhail AA, AlRashed AA, AlFawaz MA, Alsaadi MM. Determinants of asthma control among children in Saudi Arabia. J Asthma. 2014;51(4):435–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2013.876649.

Peters SP, Jones CA, Haselkorn T, Mink DR, Valacer DJ, Weiss ST. Real-world Evaluation of Asthma Control and Treatment (REACT): findings from a national Web-based survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1454–61.

Liu AH, Gilsenan AW, Stanford RH, Lincourt W, Ziemiecki R, Ortega H. Status of Asthma control in pediatric primary care: results from the pediatric asthma control characteristics and prevalence survey study (ACCESS). J Pediatr. 2010;157(2):276-281.e3.

Nagao M, Ikeda M, Fukuda N, Habukawa C, Kitamura T, Katsunuma T, Fujisawa T, LePAT (Leukotriene and Pediatric Asthma Translational Research Network) investigators. Early control treatment with montelukast in preschool children with asthma: a randomized controlled trial. Allergol Int. 2018;67(1):72–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alit.2017.04.008.

Castro-rodriguez JA, Custovic A, Ducharme FM. Treatment of asthma in young children: evidence-based recommendations. Asthma Res Pract. 2016;2:1–11.

Cruz AA, Bateman ED, Bousquet J. The social determinants of asthma. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(2):239–42.

Gebremariam TH, Sherman CB, Schluger NW. Perception of asthma control among asthmatics seen in Chest Clinic at Tertiary Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19(1):187. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-019-0959-7.

Ducharme FM, Dell SD, Radhakrishnan D, Grad RM, Watson WT, Yang CL, Zelman M. Diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers: a Canadian Thoracic Society and Canadian Paediatric Society position paper. Can Respir J. 2015;22(3):135–43. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/101572.

Murphy KR, Zeiger RS, Kosinski M, Chipps B, Mellon M, Schatz M, Lampl K, Hanlon JT, Ramachandran S. Test for respiratory and asthma control in kids (TRACK): a caregiver-completed questionnaire for preschool-aged children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(4):833-9.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2009.01.058.

Liu AH, Zeiger R, Sorkness C, Mahr T, Ostrom N, Burgess S, Rosenzweig JC, Manjunath R. Development and cross-sectional validation of the Childhood Asthma Control Test. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(4):817–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.662.

Schatz M, Sorkness CA, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray JJ, Nathan RA, Kosinski M, Pendergraft TB, Jhingran P. Asthma Control Test: reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients not previously followed by asthma specialists. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(3):549–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.011.

Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(4):304–14. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0575.

Cohen J, Mann D, Wisnivesky J, et al. Assessing the validity of self-reported medication adherence among inner-city asthmatic adults: the medication adherence report scale for asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103(4):325–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60532-7.

Coban H, Aydemir Y. The relationship between allergy and asthma control, quality of life, and emotional status in patients with asthma: a cross-sectional study. Allergy Asthma Clin Immun. 2014;10:1–7.

Ponte EV, Souza-Machado A, Souza-Machado C, Franco R, Cruz AA. Atopy is not asscoated with poor control of asthma. J Asthma. 2012;49(10):1021–6.

Marenholz I, Esparza-Gordillo J, Rüschendorf F, et al. Meta-analysis identifies seven susceptibility loci involved in the atopic march. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8804. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9804.

Lil JT, Schatz M, Sorkness CA, Murray JJ, Marcus P, Nathan RA, Pendergraft TB, Kosinski M, Stanford RH. Specialist asthma care results in superior assessment of asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(2):S253.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely acknowledge SPHMMC for funding the research and our patients for their participation.

Funding

This study was funded by SPHMMC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA and AYW conceptualize and prepare first draft of the proposal and did data analysis. AA wrote first draft. AYW wrote final draft. TGD and RAK revised study proposal, guided data collection and analysis and revised manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was provided from Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of SPHMMC, TAH and Yekatit 12 Hospital medical colleges. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all children and assent from children less than 16 years. The study was conducted based on the approved protocol and as per the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Aschalew, A., Kebed, R.A., Demie, T.G. et al. Assessment of level of asthma control and related factors in children attending pediatric respiratory clinics in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Pulm Med 22, 70 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-022-01865-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-022-01865-8