Abstract

Background

To explore patterns of brain structural alteration in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients with different levels of lung function impairment and the associations of those patterns with cognitive functional deficits using voxel-based morphometry (VBM) and tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) analyses based on high-resolution structural MRI and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI).

Methods

A total of 115 right-handed participants (26 severe, 29 moderate, and 29 mild COPD patients and a comparison group of 31 individuals without COPD) completed tests of cognitive (Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MoCA]) and pulmonary function (forced expiratory volume in 1 s [FEV1]) and underwent MRI scanning. VBM and TBSS analyses were used to identify changes in grey matter density (GMD) and white matter (WM) integrity in COPD patients. In addition, correlation analyses between these imaging parameter changes and cognitive and pulmonary functional impairments were performed.

Results

There was no significant difference in brain structure between the comparison groups and the mild COPD patients. Patients with moderate COPD had atrophy of the left middle frontal gyrus and right opercular part/triangular part of the inferior frontal gyrus, and WM changes were present mainly in the superior and posterior corona radiata, corpus callosum and cingulum. Patients with severe COPD exhibited the most extensive changes in GMD and WM. Some grey matter (GM) and WM changes were correlated with MoCA scores and FEV1.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that patients with COPD exhibit progressive structural impairments in both the GM and the WM, along with impaired levels of lung function, highlighting the importance of early clinical interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic progressive airflow restriction syndrome that is often accompanied by a variety of extrapulmonary complications. Central nervous system dysfunction is one such extrapulmonary complication [1]. Dag et al. [2] and López-Torres et al. [3] have shown that cognitive function is reduced in COPD patients; Yin et al. [4] found that cognitive impairment in COPD patients does not significantly differ by sex, region, educational level, smoking status, or alcohol drinking. The mechanism of COPD-related cognitive impairment may be associated with hypoxia-induced neurological damage [5], airway obstruction (measured by forced expiratory volume in 1 s [FEV1]) [6], and inflammatory mediators [7, 8]. However, studies on the topic have merely suggested an association rather than a causal link [9]; the mechanisms of brain pathology and cognitive impairment are likely to be complex and multi-factorial [10] and are not well understood.

To date, neuroimaging studies have found changes in brain structure, metabolism and function in patients with COPD. Ortapamuk et al. [11] found that blood flow perfusion in the frontal and parietal lobes of COPD patients was significantly reduced on SPECT. Previous studies have shown that the task and resting states of the prefrontal networks of COPD patients can be determined by functional magnetic resonance (fMRI) studies, and abnormal activation of multiple brain regions has been found [12, 13]. Zhang et al. found that the grey matter (GM) of COPD patients varied in many brain regions, such as the limbic and the paralimbic system [14]. In addition, diffuse injury was found in white matter (WM) in patients with stable COPD [15].

Previous neuroanatomical studies of COPD patients were based mainly on the classification of oxygen saturation [16]. The severity of the disease was stratified by oxygen saturation, the sample size was relatively small, and the range of damage in WM was reflected only by the fractional anisotropy (FA) value, which is not sufficiently comprehensive [15], thus introducing bias in the results. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines recommend classifying COPD severity based on pulmonary function (measured by FEV1) [17] rather than oxygen saturation. In the present study, we used a larger sample size than previous studies and divided patients into multiple sub-groups based on lung function. The aim of this study was to explore patterns of brain structural alteration in COPD patients with different levels of lung function impairment and the associations of these patterns with cognitive function deficits. We hypothesized that COPD patients would exhibit different degrees of structural impairments in both GM and WM according to their levels of lung function and that these structural impairments would be correlated with cognitive functional deficits.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 115 right-handed individuals (26 severe, 29 moderate, and 29 mild COPD patients and a comparison group of 31 individuals without COPD) participated in the study. The comparison group consisted entirely of volunteers from the community, and the COPD patients were recruited from the Pulmonary Clinic and Inpatient Department of the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University from March 2013 to December 2016. COPD was diagnosed and classified according to the 2013 GOLD guidelines [17]. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) other lung diseases; (2) comorbidities such as vascular complications of diabetes, liver failure, cardiovascular disease, neurologic disease, malignant tumours, obstructive sleep apnoea or other diseases known to affect cognition; (3) < 5 years of education; and (4) claustrophobia, ferromagnetic implants, or pacemakers [12, 15]. All participants underwent a complete physical examination administered by a respiratory physician and a neuropsychologist. All subjects provided written consent to participate and were informed of the possible risks of the study. The study was performed according to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Physiological and neuropsychological tests

The arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) and blood oxygen saturation (SaO2) were evaluated with a Stat Profile Critical Care Xpress system (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA, USA) within 24 h before MR scanning. The normal range for PaO2 was defined as PaO2>80 mmHg; mild hypoxia was defined as 60 mmHg<PaO2 ≤ 80 mmHg [18]. The normal range for SaO2 was defined as SaO2>94%; mild hypoxia was defined as 90% ≤ SaO2 ≤ 94% [19].

Patients underwent a standardized test of pulmonary function using a dry spirometer device within 24 h before MR scanning (Erich Jaeger GmbH, Hoechberg, Germany), 15 min after inhaling 400 μg of salbutamol (Ventolin; GlaxoSmithKline; London, UK); forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1, and the FEV1/FVC ratio were recorded. For patients with FEV1/FVC ratios < 0.7, disease staging was predicted based on the FEV1% as follows: FEV1% ≥ 80% predicted mild COPD; 50% ≤ FEV1% < 80% predicted moderate COPD; and 30% ≤ FEV1% < 50% predicted severe COPD [17].

The MoCA was used to assess cognitive performance [20, 21]. Data were analysed with SPSS v16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), followed by a test for homogeneity of variance. The means of the four groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance with a post hoc test to measure between-group differences. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

MRI data acquisition

All MRI examinations were performed on an MR750w 3.0 T MRI scanner with a 16-channel head coil (General Electric, Waukesha, WI, USA). We performed T1-weighted three-dimensional (3D) structural imaging, axial T2-weighted DTI spin-echo single-shot echo-planar imaging, and axial T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging. Relevant parameters can be found in Additional file 1: supplementary materials.

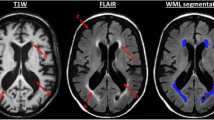

However, as the presence of mild to moderate WM hyperintensities (WMHs) commonly accompanies ageing and neurodegenerative diseases [22], we graded the WMHs using the Fazekas scale [23] on the basis of visual assessment in both periventricular (0 = absent, 1 = caps or pencil lining, 2 = smooth halo, 3 = irregular periventricular hyperintensities extending into the deep WM) and subcortical areas (0 = absent, 1 = punctate foci, 2 = foci beginning to become confluent, 3 = large confluent areas). The total Fazekas score was calculated by adding the periventricular and subcortical scores together [24] and was regressed out in the following statistical models. Detailed information can be found in Table 1.

VBM analysis

GM atrophy was assessed with modulated VBM using Statistical Parametric Mapping 12 (SPM12, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12) [25]. The 3D structural data were segmented into GM, WM, and cerebrospinal fluid using the software VBM12, and Procrustes-aligned GM images were generated by a rigid transformation. These components were normalized to the standard Montreal Neurological Institute space by affine and non-linear registrations and the diffeomorphic anatomical registration using exponentiated Lie algebra algorithm. SPM12 was used to smooth the images with an 8-mm Gaussian kernel. An F-test was used to initially identify GM areas differing among the four groups, and post hoc analyses were performed to search for pairwise differences between groups (severe vs. comparison, moderate vs. comparison, mild vs. comparison, severe vs. moderate, etc.). The significance level was set at P < 0.05, the cluster size was > 30 voxels [26], and family-wise error (FWE) correction was applied for multiple comparisons. The analyses were adjusted for age, sex, education level, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, smoking index and WMH scores.

The partial correlation analysis was as follows: 8 regions of interest (ROIs) (including the bilateral orbital part of the inferior frontal gyrus; the left superior frontal gyrus, the middle frontal gyrus, the medial orbital gyrus, the parahippocampal/fusiform gyrus, the supplementary motor cortex, and the right thalamus) were selected for clusters showing differences among the four groups, and the GM density (GMD) values were extracted from the GM maps of each individual. Partial correlations between GMD values and clinical variables (MoCA scores, FEV1 measurements, PaO2, and SaO2) were performed with sex, age, education, BMI, smoking status, smoking index and WMH scores as covariates. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) analysis

TBSS statistical analyses were performed to compare diffusion indices, including FA, mean diffusivity (MD), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD), using a permutation-based non-parametric statistical method (the randomized part of the Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain Software Library; http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FSL) [26]. First, an F-test was performed to identify the WM areas that differed among the four groups, after which post hoc analyses were carried out to identify specific differences between the severe, moderate, or mild COPD group and the comparison. The number of permutations was set at 5000. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, education level, BMI, smoking status, smoking index and WMH scores. The resultant statistical maps had a threshold of P < 0.05 and were FWE corrected for multiple comparisons using the threshold-free cluster enhancement option, which controls the rate of type I errors.

The International Consortium of Brain Mapping DTI-81 WM labels atlas was used to identify WM tracts of interest, with a total of 14 ROIs selected, including the genu, body, and splenium of the corpus callosum; the bilateral anterior corona radiata; the bilateral superior corona radiata; the bilateral cingulum; the left superior and interior longitudinal fasciculus; and the bilateral internal and left external capsule. Partial correlation analyses between imaging parameters (MD, AD or RD) and clinical variables (MoCA scores, FEV1, PaO2, SaO2) were carried out with sex, age, education, BMI, smoking status, smoking index and WMH scores as covariates. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Physiological and behavioural findings

There were no differences in age, sex, BMI, smoking status, or education among the mild, moderate, and severe COPD groups and the comparison group (P > 0.05). However, the indices of lung function (FEV1%) and blood gas parameters (PaO2 and SaO2) showed significant differences (P < 0.05), and when lung function decreased, PaO2 and SaO2 decreased (Table 1).

Total MoCA scores differed significantly among the four groups (P < 0.05). The average cognitive function score of the COPD groups was < 26, meaning that the patients had mild cognitive impairment (normal ≥26). The MoCA items scores for visuospatial executive function, attention, abstraction, delayed recall, and orientation differed significantly among the four groups (P < 0.05). The differences between groups are shown in Table 2.

Change in GMD

Compared to the comparison group, COPD patients showed widespread GM atrophy in the bilateral orbital part of the inferior frontal gyrus; the left superior frontal gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, medial orbital gyrus, parahippocampal/fusiform gyrus, and supplementary motor cortex; and right thalamus (P < 0.05, FWE corrected; Additional file 1: Table S1).

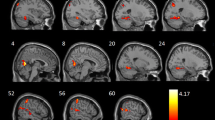

The number of brain regions with reduced GMD was not significantly different between mild COPD patients and the comparison group. Only a few brain regions (including the left middle frontal gyrus and right opercular part/triangular part of the inferior frontal gyrus) had reduced GMD in moderate COPD patients relative to the comparison group (P < 0.05, FWE corrected; Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Table S2). Brain regions with reduced GMD relative to the comparison group were more extensive in patients with severe COPD than in those with moderate COPD; multiple brain regions demonstrated atrophy in the severe COPD group. The details of these results are shown in Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Table S2 (P < 0.05, FWE corrected).

Change in WM

Significant differences in MD, AD and RD were observed among the four groups, including changes in WM integrity in the corpus callosum, cingulum, fornix, corona radiata, posterior thalamic radiation, internal capsule, external capsule (left), superior and inferior longitudinal fasciculus (left) and inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (left); the FA values were not significantly different among the four groups (P < 0.05, FWE corrected; Additional file 2: Fig. S1).

The increases in MD, AD, and RD in mild COPD patients relative to the comparison group were not statistically significant. Moderate COPD patients showed increases in MD and AD in the splenium of the corpus callosum, left posterior corona radiata and external capsule relative to the comparison group. Additional increases in MD were detected in the right superior corona radiata, genu and body of the corpus callosum; the left posterior thalamic radiation; and the bilateral cingulum (cingulate gyrus). RD was observed in the left longitudinal fasciculus (Fig. 2).

TBSS results showing the differences in diffusion indices between moderate COPD patients and the comparison group Note: Green represents the mean WM skeleton of all subjects; yellow, red and blue represent regions with increased MD, increased AD and increased RD, respectively, in moderate COPD patients (P < 0.05, FWE corrected). Abbreviations: TBSS, tract-based spatial statistics; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NCs, normal controls; WM, white matter; MD, mean diffusivity; AD, axial diffusivity; and RD, radial diffusivity

Relative to the comparison group, the severe COPD patients showed the most extensive changes in WM integrity, including increased MD, AD and RD values in the bilateral posterior corona radiate; the left anterior and superior corona radiata, left cingulum (cingulate gyrus); the left posterior thalamic radiation; the left anterior limb of the internal capsule; the left external capsule; and the genu, body and splenium of the corpus callosum. Additional increases in MD or RD were observed in the fornix, bilateral cingulum (cingulate gyrus), right anterior and superior corona radiata, left posterior limb of the internal capsule, left superior and inferior longitudinal fasciculus, and left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (Fig. 3).

TBSS results of the differences in diffusion indices between severe COPD patients and the comparison group Note: Green represents the mean WM skeleton of all subjects; yellow, red and blue represent regions with increased MD, increased AD, and increased RD, respectively, in severe COPD patients (P < 0.05, FWE corrected). Abbreviations: TBSS, tract-based spatial statistics; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NCs, normal controls; WM, white matter; MD, mean diffusivity; AD, axial diffusivity; and RD, radial diffusivity

Correlational analysis

There was no statistically significant correlation between GMD or WM changes and PaO2 or SaO2.

In the COPD group, the GMDs in the left superior frontal gyrus and right orbital part of the inferior frontal gyrus were positively correlated with MoCA scores (r = 0.233, P = 0.048; r = 0.293, P = 0.009, respectively) and FEV1 values (r = 0.433, P<0.001; r = 0.659, P<0.001; Table 3 and Fig. 4). The MD and RD values of the body of the corpus callosum and the AD value of the bilateral superior corona radiata were negatively correlated with FEV1 and MoCA scores (Table 3 and Additional file 1: Table S3).

Correlation analyses among MoCA scores, FEV1, and GMD in COPD patients. Abbreviations: MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; R-OPIFG, right orbital part of the inferior frontal gyrus; and L-SFG, left superior frontal gyrus

Discussion

In this study, we found that the MoCA scores of patients with COPD were gradually reduced from mild to severe COPD. Moreover, the brain structures of the abovementioned groups of COPD patients showed a trend of progressive change.

We found that COPD patients’ scores on MoCA items that measure aspects of executive function, attention and delayed memory were lower than the comparison group, similar to the results of a previous study demonstrating that irreversible restriction of airflow in COPD patients may result in a reduced oxygen supply, which may cause damage to neurons in the brain, and continuous hypoxia may damage people’s delayed recall and attention [27]. Incalzi et al. [28] also found that COPD patients with hypoxia and high carbon dioxide levels had a characteristic pattern of cognitive decline characterized by disorders of executive function and attention. The literature has demonstrated the presence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea syndrome (OSAHS); evaluation of MoCA items further revealed selective reductions in visuospatial skills, executive function, attention and delayed memory, and MoCA scores were correlated significantly with serum levels of TNF-α [29]. Crisan et al. [30] found that low FEV1 was associated with decreased MoCA scores. These results support our findings and suggest that the cognitive impairment accompanying COPD may be caused by hypoxia, carbon dioxide retention, inflammatory factors or pulmonary dysfunction.

Relative to the comparison group, the GMD of patients with COPD was mainly reduced in the prefrontal cortex, limbic system structures and thalamus, which was partially consistent with the findings of Zhang et al. [15] and similar to results from patients with sleep apnoea syndrome [31,32,33]. We found that the GMD was decreased in the left superior frontal gyrus, left orbital part of the inferior frontal gyrus, left medial orbital gyrus, and left middle frontal gyrus, which mainly participate in high-level cognitive functions (e.g., visual motion synchronization, language fluency, and executive functions) [34]. The dorsal cortex of the prefrontal cortex and the dorsal prefrontal cortex of the frontoparietal network were obviously atrophied, which may lead to declines in visual memory and reconstruction in COPD patients [16]. We also observed that the GMD in the limbic system (parahippocampal gyrus) was decreased in COPD patients. The parahippocampal gyrus is a key area of the limbic system that plays an important role in the regulation of emotion, motivation and memory [35, 36]. Limbic structures are connected to the frontal and temporal lobes and have subcortical connections that are critical for cognition and memory [37]. Thus, GM damage in these areas may lead to impairments in cognition and memory. The thalamus plays an important role in the Papez circuit and is connected to the medial temporal lobe [38], which is essential for episodic memory [39]. GM damage to the thalamus can affect cognitive memory functions. Abnormal neuronal activity in the prefrontal-limbic network, including the dorsal prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortices and the parahippocampal gyrus, is associated with a decrease in working memory [40].

FA is sensitive to microstructural changes; MD is a measure of total diffusion within a voxel [41]; AD increases in WM tracts with brain maturation and is sensitive to axonal injury; and RD is sensitive to axonal diameters and demyelination [42]. Thus, a significant decrease in FA and increases in AD and RD indicate the possibility of injury to axons and/or myelin [41, 43]. However, we did not find any significant difference in FA values among the four groups. FA is affected by MD, AD and RD [44]. However, when the values of MD, AD and RD increase simultaneously, the FA value may not change, which was observed in our research.

Therefore, in this study, we combined these three values to observe changes in WM microstructure in COPD patients. We found that WM changes in COPD patients were localized mainly in the corona radiata, cingulate gyrus, corpus callosum and superior and inferior longitudinal fasciculus, and the changes in the severe group were more extensive than those in the moderate group. WM changed more broadly than GM. Although WM, which occupies 50% of the total brain volume in humans, has a metabolic rate similar to that of GM [45, 46], WM receives a disproportionately small blood supply and little collateral circulation, making it particularly susceptible to ischaemic insults [46, 47], in which chronic systemic inflammation, tissue hypoxia and oxidative stress play crucial roles [48]. Axonal changes interfere with the communication between brain structures and thus alter the functions of these structures [49].

We found that the GMD of the left superior frontal gyrus and right orbital part of the inferior frontal gyrus, the MD and RD of the body of the corpus callosum and the AD of the bilateral superior corona radiata were correlated with FEV1 and MoCA scores. Previous studies showed that the left side of the superior frontal cortex exhibited greater thinning [50] and that there was impaired functional connectivity with the bilateral inferior frontal gyrus in obstructive sleep apnoea [51]. The superior corona radiata, an associated fibre tract in the prefrontal cortex, is connected to the internal capsule. The body of the corpus callosum comprises commissural fibres that connect the bilateral cerebral hemispheres. All three of the aforementioned fibre tracts are involved in cognitive function in COPD patients. We speculate that persistent reductions in lung function may lead to atrophy of the left superior frontal gyrus and right orbital part of the inferior frontal gyrus as well as WM changes in the body of the corpus callosum and bilateral superior corona radiata, ultimately resulting in cognitive impairment.

However, we did not find a clear correlation between PaO2 or SaO2 and brain structural changes in COPD patients, suggesting that hypoxia may not be the main mechanism of brain structural changes and cognitive impairment in this disease. The brain pathological mechanism of cognitive impairment in COPD patients may be very complex. Savchenko et al. and Sakurai et al. found that FEV1 was negatively correlated with the systemic inflammatory factor IL-26 [52], a biomarker of inflammation. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is associated with the severity of COPD [53]. Inflammatory factor ‘spill-over’ [54] may cause cognitive impairment in COPD patients. Wang et al. [55] studied brain activity in stable patients with COPD and found that the mean signal values in the cluster with reduced amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) were significantly negatively correlated with PaCO2. Inflammatory factors or carbon dioxide retention may be potential mechanisms that merit further attention in future research.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, we did not include comprehensive neuropsychological assessments of the comparison and COPD groups; this omission may have introduced some bias in the classification of groups. Second, we used only the MoCA to assess the patients’ cognitive status; the items included on the MoCA are limited in their ability to measure subdomains of cognition. In the future, comprehensive neuropsychological assessment could be used to fully evaluate patients’ cognition. Third, patients with COPD often have more additional medical problems, which we listed an exclusion criterion. The exclusion of patients with comorbidities can limit the representativeness of the sample; however, we used a long scan time, and COPD patients with other severe illnesses may have faced discomfort if they had participated. Fourth, the study was cross-sectional and showed that lung function in COPD patients was related to changes in brain structure and cognitive function. Previous studies have shown that long-term oxygen therapy and exercise can improve lung and, to some extent, cognitive function [27]. A longitudinal study examining the role of pulmonary function as an independent factor in COPD is planned for the future. Fifth, patients with COPD used steroids to relieve symptoms during an acute attack. Although studies [56] have shown that steroids cause changes in brain structure, they are necessary for humane patient care. Finally, we did not perform multiple comparison correction for the correlation analyses between imaging parameters and MoCA and FEV1. However, our study is exploratory in nature, and the results showed a modest strength of the association that cannot pass the multiple comparison correction. In the future, we would increase the sample size and make more stringent adjustment.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that patients with COPD exhibit progressive structural impairments in both GM and WM, along with impaired levels of lung function, highlighting the importance of early clinical interventions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

axial diffusivity

- ANOVA:

-

analysis of variance.

- COPD:

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DTI:

-

diffusion tensor imaging

- FA:

-

fractional anisotropy

- FEV1:

-

forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- GMD:

-

grey matter density

- MD:

-

mean diffusivity

- MoCA:

-

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- RD:

-

radial diffusivity

- TBSS:

-

tract-based spatial statistics

- VBM:

-

voxel-based morphometry

- WM:

-

white matter

References

Dodd JW, Getov SV, Jones PW. Cognitive function in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(4):913–22.

Dag E, Bulcun E, Turkel Y, Ekici A, Ekici M. Factors influencing cognitive function in subjects with COPD. Respir Care. 2016;61(8):1044–50.

López-Torres I, Valenza MC, Torres-Sánchez I, Cabrera-Martos I, Rodriguez-Torres J, Moreno-Ramírez MP. Changes in cognitive status in COPD patients across clinical stages. COPD. 2016;13:327–32.

Yin P, Ma Q, Wang L, Lin P, Zhang M, Qi S, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cognitive impairment in the Chinese elderly population: a large national survey. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:399–406.

Heaton RK, Grant I, McSweeny AJ, Adams KM, Petty TL. Psychologic effects of continuous and nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1941–7.

Cleutjens FAHM, Spruit MA, Ponds RWHM. Dijkstra JB3, Franssen FME2, Wouters EFM, et al. Cognitive functioning in obstructive lung disease: results from the United Kingdom biobank J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:214–9.

Duong T, Acton PJ, Johnson RA. The in vitro neuronal toxicity of pentraxins associated with Alzheimer’s disease brain lesions. Brain Res. 1988;813:303–12.

Wärnberg J, Gomez-Martinez S, Romeo J, Díaz LE, Marcos A. Nutrition, inflammation, and cognitive function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1153:164–75.

Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Meijer J, Kiliaan A, Ruitenberg A, van Swieten JC, et al. Inflammatory proteins in plasma and the risk of dementia: the Rotterdam study. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:668–72.

Dodd JW. Lung disease as a determinant of cognitive decline and dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7(1):32.

Ortapamuk H, Naldoken S. Brain perfusion abnormalities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: comparison with cognitive impairment. Ann Nucl Med. 2006;20:99–106.

Dodd JW, Chung AW, van den Broek MD, Barrick TR, Charlton RA, Jones PW. Brain structure and function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a multimodal cranial magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:240–5.

Herigstad M, Hayen A, Evans E, Hardinge FM, Davies RJ, Wiech K, et al. Dyspnea-related cues engage the prefrontal cortex: evidence from functional brain imaging in COPD. Chest. 2015;148:953–61.

Zhang H, Wang X, Lin J, Sun Y, Huang Y, Yang T, et al. Reduced regional gray matter volume in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a voxel-based morphometry study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:334–9.

Zhang H, Wang X, Lin J, Sun Y, Huang Y, Yang T, et al. Grey and white matter abnormalities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a case–control study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000844.

Chen J, Lin IT, Zhang H, Lin J, Zheng S, Fan M, et al. Reduced cortical thickness, surface area in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a surface-based morphometry and neuropsychological study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2016;10:464–76.

Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(4):347–65.

Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Marcus JT, Holverda S, Roseboom B, Postmus PE. Early changes of cardiac structure and function in COPD patients with mild hypoxemia. Chest. 2005;127(6):1898–903.

Silva JLR. Júnior, Conde MB, Corrêa KS, Rabahi H, Rocha AA, Rabahi MF. Sleep-disordered breathing in patients with COPD and mild hypoxemia: prevalence and predictive variables. J Bras Pneumol. 2017;43(3):176–82.

Tudorache E, Fildan AP, Frandes M, Dantes E, Tofolean DE. Aging and extrapulmonary effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:1281–7.

Verstraeten E, Cluydts R, Pevernagie D, Hoffmann G. Executive function in sleep apnea: controlling for attentional capacity in assessing executive attention. Sleep. 2004;27:685–93.

Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, Cordonnier C, Fazekas F, Frayne R. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:822–38.

Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer’s dementia and normal aging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:351–6.

Helenius J, Mayasi Y, Henninger N. White matter hyperintensity lesion burden is associated with the infarct volume and 90-day outcome in small subcortical infarcts. ActaNeurol Scand. 2016;135:585–592.

Li X, Wang H, Tian Y. Zhou S2, Li X1, Wang K, et al. Impaired White Matter Connections of the Limbic System Networks Associated with Impaired Emotional Memory in Alzheimer's Disease Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:250.

Lai CH, Wu YT. Fronto-temporo-insula gray matter alterations of first-episode, drug-naïve and very late-onset panic disorder patients. J Affect Disord. 2012;140:285–91.

Dal Negro RW, Bonadiman L, Bricolo FP, Tognella S, Turco P. Cognitive dysfunction in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with or without long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT). Multidiscip Respir Med. 2015;10(1):17.

Antonelli Incalzi R, Marra C, Giordano A, Calcagni ML, Cappa A, Basso S, et al. Cognitive impairment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease--a neuropsychological and spect study. J Neurol. 2003;250:325–32.

Sun L, Chen R, Wang J, Zhang Y, Li J, Peng W, et al. Association between inflammation and cognitive function and effects of continuous positive airway pressure treatment in obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2014;94:3483–7.

Crişan AF, Oancea C, Timar B, Fira-Mladinescu O, Crişan A, Tudorache V. Cognitive impairment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102468.

Chan KC, Shi L, So HK, Wang D, Liew AWC, Rasalkar DD, et al. Neurocognitivedysfunction and grey matter density deficit in children with obstructive sleepapnoea. Sleep Med. 2014;15:1055–61.

Joo EY, Tae WS, Lee MJ, Kang JW, Park HS, Lee JY, et al. Reduced brain gray matter concentration in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 2010;33:235–241.

Weng HH, Tsai YH, Chen CF, Lin YC, Yang CT, Tsai YH, et al. Mapping gray matter reductions in obstructive sleep apnea: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Sleep. 2014;37:167–75.

Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:167–202.

Fang J, Jin Z, Wang Y, Li K, Kong J, Nixon EE, et al. The salient characteristics of the central effects of acupuncture needling: limbic–paralimbic–neocortical network modulation. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:1196–206.

Fossati P. Neural correlates of emotion processing: from emotional to social brain. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(Suppl 3):S487–91.

Price JL, Drevets WC. Neurocircuitry of mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:192–216.

Van der Werf YD, Jolles J, Witter MP, Uylings HB. Contributions of thalamic nuclei to declarative memory functioning. Cortex. 2003;39:1047–62.

Aggleton JP, O'Mara SM, Vann SD, Wright NF, Tsanov M, Erichsen JT. Hippocampal-anterior thalamic pathways for memory: uncovering a network of direct and indirect actions. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:2292–307.

Brooks JO, Rosen AC, Hoblyn JC, Woodard SA, Krasnykh O, Ketter TA. Resting prefrontal hypometabolism and paralimbic hypermetabolism related to verbal recall deficits in euthymic older adults with bipolar disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:1022–9.

Fidan E, Foley LM, New LA, Alexander H, Kochanek PM, Hitchens TK, et al. Metabolic and structural imaging at 7 tesla after repetitive mild traumatic brain injury in immature rats. ASN Neuro. 2018;10:1759091418770543.

Kubicki M, McCarley R, Westin CF, Park HJ, Maier S, Kikinis R, et al. A review of diffusion tensor imaging studies in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:15–30.

Umarova RM, Beume L, Reisert M, Kaller CP, Klöppel S, Mader I, et al. Distinct white matter alterations following severe stroke: longitudinal DTI study in neglect. Neurology. 2017;88:1546–55.

Alexander AL, Lee JE, Lazar M, Field AS. Diffusion tensor imaging of the brain. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4(3):316–29.

Goldberg MP, Ransom BR. New light on white matter. Stroke. 2003;34:330–2.

Dewar D, Yam P, McCulloch J. Drug development for stroke: importance of protecting cerebral white matter. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;375:41–50.

Arai K, Lo EH. Oligovascular signaling in white matter stroke. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:1639–44.

Geltser BI, Kurpatov IG, Kotelnikov VN, Zayats YV. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cerebrovascular diseases: functional and clinical aspect of comorbidity. TerArkh. 2018;90:81–8.

Kanaan A, Farahani R, Douglas RM, Lamanna JC, Haddad GG. Effect of chronic continuous or intermittent hypoxia and reoxygenation on cerebral capillary density and myelination. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1105–14.

Macey PM, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Prasad JP, Ma RA, Kumar R, Philby MF, et al. Altered regional brain cortical thickness in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Front Neurol. 2018;9:4.

Song X, Roy B, Kang DW, Aysola RS, Macey PM, Woo MA, et al. Altered resting-state hippocampal and caudate functional networks in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Brain Behav. 2018;8:e00994.

Savchenko L, Mykytiuk M, Cinato M, Tronchere H, Kunduzova O, Kaidashev I. IL-26 in the induced sputum is associated with the level of systemic inflammation, lung functions and body weight in COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:2569–75.

Sakurai K, Chubachi S, Irie H, Tsutsumi A, Kameyama N, Kamatani T, et al. Clinical utility of blood neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in Japanese COPD patients. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18(1):65.

Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Systemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1165–85.

Wang W, Li H, Peng D, Luo J, Xin H, Yu H, et al. Abnormal intrinsic brain activities in stable patients with COPD: a resting-state functional MRI study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:2763–72.

Murphy BP, Inder TE, Huppi PS, Warfield S, Zientara GP, Kikinis R, et al. Impaired cerebral cortical gray matter growth after treatment with dexamethasone for neonatal chronic lung disease. Pediatrics. 2001;107:217–21.

Acknowledgements

We thank Xiaoyan Han for assisting us with the clinical data collection.

We thank Dr. Jiajia Zhu for helping us modify the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 81171326, 81571308, and 81771817).

The funders had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YQY and GHF drafted the research proposal. HBW, YQY, and GHF designed the experiments. MMY and XWH performed the experiments. MMY, HBW and XSL analysed the data. MMY and HBW wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved this submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University; written informed consent has been obtained from all subjects prior to participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Brain areas with significant inter-group differences in GMD according to analysis of variance. Table S2. Brain areas with significant GMD decreases in severe and moderate COPD patients. Table S3. Correlation analysis between WM parameters and (MoCA scores and FEV1) in COPD.

Additional file 2: Figure S1.

TBSS results of diffusion indices in the four groups. Note: Extensive WM differences were observed among the four groups in various brain regions. Green represents the mean WM skeleton of all subjects; yellow, red and blue represent regions with significantly different MD, AD, and RD, respectively (P < 0.05, FWE corrected). Abbreviations: TBSS, tract-based spatial statistics; WM, white matter; MD, mean diffusivity; AD, axial diffusivity; and RD, radial diffusivity.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, M., Wang, H., Hu, X. et al. Patterns of brain structural alteration in COPD with different levels of pulmonary function impairment and its association with cognitive deficits. BMC Pulm Med 19, 203 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-019-0955-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-019-0955-y