Abstract

Background

In Latin America, there is scarce information about severe asthma (SA) according to the ERS/ATS 2014 criteria. This study aimed to compare the demographic, socio, clinical characteristics, treatment, and use of healthcare resources between SA and non-severe asthma (NSA) patients in Argentina, Colombia, Chile and Mexico.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted including 594 asthma patients from outpatient specialized sites. A descriptive analysis was performed comparing SA patients and NSA. Chi-square and Mann Whitney tests were used to assess associations between asthma severity and outcome variables.

Results

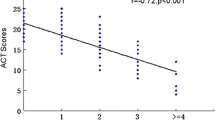

Using ERS/ATS 2014 criteria, 31.0% of the patients were identified as SA. SA patients were older at diagnosis (mean age 31.64 years vs 24.71 years, p < 0.001) and had higher proportion of uncontrolled asthma than the NSA patients (64.1% vs 53.2%, p < 0.001). SA patients reported a significantly higher proportion of both hospital admission and emergency room (ER) visits due to asthma in the last year, compared with NSA patients, 8.7% vs. 3.7% (p = 0.011) and 37.0% vs. 21.7% (p < 0.001), respectively.

Conclusions

SA patients were older, had greater proportions in some comorbidities and experienced increased healthcare utilization. Also, our results showed that even in patients using the last steps of treatment (GINA step 4 or 5), there was still a higher proportion of uncontrolled disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways [1] and its prevalence is estimated to range from 0.2 to 21.0% globally [2]. It is one of the most common chronic diseases among children [3] and young adults [2], and it is a significant cause of disability, high health resource utilization, and poor quality of life for those who are affected [1]. Thus, it accounts for considerable healthcare costs and loss of work productivity [4, 5].

Approximately 2–10% have some form of severe asthma (SA) [6, 7]. According to ERS/ATS 2014 guidelines [8], SA is defined as asthma that requires step four or five treatment (e.g. high-dose Inhaled Corticosteroids (ICS)/Long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA)) to prevent it from becoming ‘uncontrolled’, or asthma that remains ‘uncontrolled’ despite this treatment. SA is a heterogeneous disease with high variability in clinical presentation, physiological characteristics, and disease manifestation [6, 9].

In Latin America, there is a lack of information related to SA epidemiology and the burden of SA following implementation of the ERS/ATS 2014 criteria. Essentially, most of the Latin American studies that have assessed the SA population in the region had also included untreated patients [10, 11] or focused on the, uncontrolled asthma population [12]. Therefore, by using the ERS/ATS 2014 criteria the aims of this study were to compare the demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics, as well as treatment courses and use of healthcare resources between SA patients and non-severe asthma (NSA) patients in Argentina, Colombia, Chile, and Mexico.

Methods

Study design and population

The Asthma Control in Latin America (ASLA) study was a cross-sectional multisite study. Patients were consecutively enrolled between December 2013 and December 2015. The 16 recruiting sites were located in Argentina (five sites); Chile (five sites), Colombia (three sites), and Mexico (three sites) [13, 14].

The study included 594 diagnosed and treated asthma patients who were recruited during routine care at specialized outpatient sites, aged over 12 years old, under pneumologists follow up, with at least one prescription of asthma medication and one medical visit for asthma within the last 6 months. Individuals were excluded if they were participating in a clinical trial at the time of the study or were unable or not willing to comply with the study requirements. This study was conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki [15]. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Minors younger than 18 years old signed the assent form and parents or legal guardians provided their written informed consent. Institutional review boards in each country approved consent forms and procedures.

Measurements

During the course of a scheduled medical visit, the participating patients were asked to complete the Asthma Control Test (ACT) [16], which was a self-administered questionnaire containing five items that can each be rated on a five-point Likert scale. Based on the ACT score, subjects were categorized as controlled (ACT score ≥ 20) or uncontrolled (ACT score < 20). The physician conducted an interview, which included questions on socio-demographic data [gender, age, skin colour (white, African-Latin American, Native American, multiple and other skin colours that were not listed)]; healthcare utilization in the last year; treatment used; and comorbidities.

Asthma severity was operationally defined using an algorithm based on answers to questions relating to the ERS/ATS 2014 criteria. SA was defined as asthma that required step four or five treatment (i.e.: high ICS doses plus a second controller or use of OCS (oral corticosteroid) regardless of ICS doses). Four treatment categories did not fulfil the ERS/ATS 2014 criteria for SA and NSA and were reviewed by a panel of three pneumologist experts on asthma to allocate a group (Table 1). Clinically significant asthma exacerbations were based on patients self-reported healthcare resource utilization, and were defined as any emergency room (ER) visit or hospitalization due to asthma.

Data Analysis

A descriptive analysis was carried out, comparing socio-demographic characteristics, clinical factors, asthma control, nutritional status, healthcare utilization in the last year, treatment used, and comorbidities of SA patients compared with NSA patients.

Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated in adults as weight divided by the square of height, and the nutritional status categorized as: underweight < 18.5 Kg/m2; eutrophic = 18.5–24.9 Kg/m2; overweight = 25–29.9 Kg/m2; and obesity ≥30Kg/m2. BMI in adolescents was calculated following the indications described elsewhere [17] and the nutritional status classified as underweight (Z-score < − 3 and < − 2); eutrophic (Z-score ≥ − 2 and ≤ 1); overweight (score-Z > 1 and ≤ 2); and obese (Z-score > 2). For demographic and clinical outcome variables, Chi-square test or the Fisher exact test (as appropriate) and Mann Whitney test were used to assess associations between SA patients and NSA patients. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using Stata™13 College Station,TX: StataCorpLP and SPSS™ version 24.

Results

A total of 594 asthma patients were studied: 154 subjects from Argentina, 154 from Chile, 163 from Mexico and 123 from Colombia. Overall 72.7% were women and 50.8% white, with a median age of 47 years old at the time of the study visit and an age of 25 at the time of asthma diagnosis. According to the ERS/ATS 2014 criteria, 31.0% of the patients had SA (Table 2). Among the SA patients, 88.0% were classified as SA by the use of high ICS dose plus a second controller (Table 4). Of the 12% remaining, about 11.4% used ICS in doses that were not high but were classified as SA due to the use of anti-IgE, tiotropium, anti-IgE and tiotropium at the same time or OCS. The last 0.6% used OCS without ICS in combination and due to that it was also considered as SA.

Differences in socio-demographic and clinical factors by SA and NSA are shown in Table 2. NSA patients were younger than the SA patients at study visit and at diagnosis. 72.1% of the SA patients were overweight or obese. A higher proportion of SA patients reported having performed at least one PEF test in the last year compared with NSA patients (35.9% vs. 16.6%, p < 0.001).

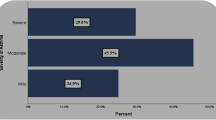

Figure 1 shows that more than a half of SA (64.1%) and NSA (53.2%) patients were uncontrolled, and this proportion was higher in SA when compared to NSA (p = 0.013).

Table 3 shows healthcare resources used and the number of clinically significant asthma exacerbation suffered during the last year by SA and NSA patients. Overall, SA patients reported a statistically significant two times higher proportion of both hospital admission (8.7% vs. 3.7%, p = 0.011) and almost two times higher proportion for ER visits due to asthma (37.0% vs. 21.7%, p < 0.001)) in the last year, compared with NSA patients.

Regarding the hospital admission and emergency visits due to other causes, SA patients also had a significant higher proportion of both events than NSA patients (6.5% vs 2.4%, p = 0.015 and 14.1% vs 7.3%, p = 0.009). The same pattern was observed when considering the mean number of clinically significant asthma exacerbations (mean 1.88 vs 0.56, p < 0.001).

When comparing use of current asthma medication by asthma severity classification (Table 4), the most common medication used in SA patients was ICS (99.5%), even in NSA patients (88.0%). Nevertheless, when comparing combination therapies (Table 5), the most prescribed was ICS/LABA, followed by ICS only in the overall population (49.0 and 17.3%, respectively). The most controller therapy used was ICS/LABA for both SA (47.8%) and NSA (49.5%) patients.

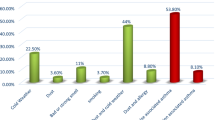

Finally, when comparing SA with NSA patients regarding self-reported comorbidities (Table 6), the most reported among the SA patients were chronic rhinitis (52.7%) followed by hypertension/hypertension syndrome (32.1%) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (27.2%). On the other hand, among the NSA patients the most frequent reported comorbidities were chronic rhinitis (56.8%), followed by chronic sinusitis and/or rhinosinusitis (22.2%) and gastroesophageal reflux (17.1%). Nevertheless, hypertension, COPD, psychological disturbances (as depression and anxiety), gastroesophageal reflux disease and obesity were higher in SA and this difference was statistically significant.

Discussion

To our knowledge, there are no previous description of the SA population in Latin America countries following the updated 2014 ERS/ATS criteria. Results from the present cross-sectional study showed that overall prevalence of SA is 31.0% among patients from outpatient specialized sites in Argentina, Chile, Colombia and Mexico. We found that patients reflecting the ERS/ATS steps 4 and 5 tended to be diagnosed at a later age, had higher proportion of hypertension, COPD, psychological disturbances, gastroesophageal reflux disease, obesity, and experienced increased healthcare utilization.

In our study, we observed that SA patients were older at the time of study and at the time of asthma diagnosis when compared with NSA patients - which is in alignment with other studies [18, 19]. This might be explained by the generalized decline in lung function in older patients, leading to more severe patients [20]. However, our study is limited to reinforce this idea due to lack of a longitudinal analysis and a multivariable analysis controlled by possible confounders.

It is worth noting from our results that despite the use of high doses of ICS in the SA group, more than 60% of them were uncontrolled, proportion that was higher when compared with NSA. Even in the overall population attending those specialized sites, 56.6% were uncontrolled. This was consistent with other studies, where SA patients had an increased number of exacerbations, as well as higher rates of hospital admissions and ER attendances [19].

Current asthma management guidelines acknowledge that PEF monitoring during exacerbations of asthma help determine the severity of these flares and can be useful to guide therapeutic decisions [8]. However, in our study less than 40% in both SA and NSA patients reported using PEF meter at least once in the last year. This low proportion is in accordance with the AIRLA study [10], which evaluated the impact of asthma in Latin America and showed that 54% of asthma patients ever had no spirometry and 96% had not ever performed a PEF test, according to patient self-reported surveys. Although there are differences in methodologies between our study and AIRLA study, which is population-based, both data reinforce that spirometry is not common in Latin America region and the reasons for that should be further evaluated.

As other studies have described that SA patients often display a high number of comorbidities [12, 21], our results found relevant differences between SA and NSA patients with regards to obesity, hypertension, COPD, psychological disturbances and gastroesophageal reflux disease. The SA Research Program (SARP) also showed that hypertension, obesity and gastroesophageal reflux disease are associated with SA [22]. Specially for hypertension, it is a significant predictor for asthma severity, but this relationship was found predominately among the white population, rather than in black patients [23]. It is important to take into account that aging could be a confounding factor in the association found between SA and comorbidities observed in our study. For psychological disturbances, the literature already described higher levels of anxiety and depression in SA patients [24, 25], which is in line with the results found in our study. Finally, COPD has been recently described to be higher in SA group by other authors [26, 27].

The external validity of the current study is limited, as most patients were recruited from specialized asthma clinics and the sample size for ASLA study was not calculated to be representative for each country. Another limitation of our study is the cross-sectional evaluation of medication use, as we did not capture the treatment step up and step down through the past years. The comparison between our result and other studies is difficult, mainly due to the fact that most part of the studies refers to the prevalence of refractory asthma and not to SA. Our analysis may also be subject to recall bias.

Conclusion

The results of our study may support the identification of SA in our region contributing to the better management of these patients. What is more, this study highlights the need to improve the asthma control in these patients that are already being treated with high ICS doses. Furthermore, complexity of SA phenotypes would require deeper investigations to determine specific phenotypes to be able to prescribe the precise therapy to increase the level of control in SA patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

Asthma control test

- Anti-IgE:

-

Anti-immunoglobulin E

- ASLA:

-

Asthma control in Latin America study

- ATS:

-

American Thoracic Society

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- ER:

-

Emergency room

- ERS:

-

European Respiratory Society

- ICS:

-

Inhaled corticosteroids

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- LABA:

-

Long-acting beta2-agonist

- LAMA:

-

Long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist

- LTRA:

-

Leukotriene receptor antagonists

- NSA:

-

Non-severe asthma

- OCS:

-

Oral corticosteroid

- PEF:

-

Peak expiratory flow

- SA:

-

Severe asthma

- SABA:

-

Short-acting beta2-agonists

- USD:

-

United States Dollars

References

Braman SS. The global burden of asthma. Chest. 2006;130(1 Suppl):4s–12s.

To T, Stanojevic S, Moores G, Gershon AS, Bateman ED, Cruz AA, Boulet L-P. Global asthma prevalence in adults: findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):204.

Deng Q, Lu C, Norbäck D, Bornehag C-G, Zhang Y, Liu W, Yuan H, Sundell J. Early life exposure to ambient air pollution and childhood asthma in China. Environ Res. 2015;143:83–92.

Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, Beasley R. The global burden of asthma: executive summary of the GINA dissemination committee report. Allergy. 2004;59(5):469–78.

Sullivan PW, Campbell JD, Ghushchyan VH, Globe G, Lange J, Woolley JM. Characterizing the severe asthma population in the United States: claims-based analysis of three treatment cohorts in the year prior to treatment escalation. J Asthma. 2015;52(7):669–80.

Poon AH, Hamid Q. Severe asthma: have we made Progress? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(Suppl 1):S68–77.

Antonicelli L, Bucca C, Neri M, De Benedetto F, Sabbatani P, Bonifazi F, Eichler HG, Zhang Q, Yin DD. Asthma severity and medical resource utilisation. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(5):723–9.

Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, Bush A, Castro M, Sterk PJ, Adcock IM, Bateman ED, Bel EH, Bleecker ER, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Resp J. 2014;43(2):343–73.

Horak F, Doberer D, Eber E, Horak E, Pohl W, Riedler J, Szépfalusi Z, Wantke F, Zacharasiewicz A, Studnicka M. Diagnosis and management of asthma - statement on the 2015 GINA guidelines. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2016;128(15–16):541–54.

Neffen H, Fritscher C, Schacht FC, Levy G, Chiarella P, Soriano JB, Mechali D. Asthma control in Latin America: the asthma insights and reality in Latin America (AIRLA) survey. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2005;17(3):191–7.

Franco R, Santos AC, do Nascimento HF, Souza-Machado C, Ponte E, Souza-Machado A, So L, Barreto ML, Rodrigues LC, Aa C. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a state funded programme for control of severe asthma. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:82.

de Carvalho-Pinto RM, Cukier A, Angelini L, Antonangelo L, Mauad T, Dolhnikoff M, Rabe KF, Stelmach R. Clinical characteristics and possible phenotypes of an adult severe asthma population. Respir Med. 2012;106(1):47–56.

Neffen HE, Vallejo-Perez E, Chahuan M, Giugno E, Hernández-Colín DD, Bolivar F, Levy G, Vieira C, Moraes F, Viana KP, et al. Uncontrolled asthma in specialized centers in Latin America: findings from the asthma control in Latin America (ASLA) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(2):–AB206.

Neffen H, Chahuàn M, Hernández DD, Vallejo-Perez E, Bolivar F, Sánchez MH, Galleguillos F, Castaños C, Orellana RS, Giugno E, et al. Key factors associated with uncontrolled asthma – the asthma control in Latin America study. J Asthma. 2019:1–10.

Rickham PP. Human experimentation. Code of ethics of the world medical association. Declaration of Helsinki. British Med J. 1964;2(5402):177.

Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray JJ, Pendergraft TB. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(1):59–65.

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(9):660–7.

Bavbek S, Celik G, Ediger D, Mungan D, Sin B, Demirel YS, Misirligil Z. Severity and associated risk factors in adult asthma patients in Turkey. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85(2):134–9.

Moore WC, Bleecker ER, Curran-Everett D, Erzurum SC, Ameredes BT, Bacharier L, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Chung KF, Clark MP, et al. Characterization of the severe asthma phenotype by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's severe asthma research program. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(2):405–13.

Ronmark E, Lindberg A, Watson L, Lundback B. Outcome and severity of adult onset asthma--report from the obstructive lung disease in northern Sweden studies (OLIN). Respir Med. 2007;101(11):2370–7.

Araujo AC, Ferraz E, Borges Mde C, Filho JT, Vianna EO. Investigation of factors associated with difficult-to-control asthma. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33(5):495–501.

Teague WG, Phillips BR, Fahy JV, Wenzel SE, Fitzpatrick AM, Moore WC, Hastie AT, Bleecker ER, Meyers DA, Peters SP, et al. Baseline Features of the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP III) Cohort: Differences with Age. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(2):545–554.e544.

Gamble C, Talbott E, Youk A, Holguin F, Pitt B, Silveira L, Bleecker E, Busse W, Calhoun W, Castro M, et al. Racial differences in biologic predictors of severe asthma: data from the severe asthma research program. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6):1149–1156.e1141.

Shaw DE, Sousa AR, Fowler SJ, Fleming LJ, Roberts G, Corfield J, Pandis I, Bansal AT, Bel EH, Auffray C, et al. Clinical and inflammatory characteristics of the European U-BIOPRED adult severe asthma cohort. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(5):1308–21.

Sweeney J, Patterson CC, Menzies-Gow A, Niven RM, Mansur AH, Bucknall C, Chaudhuri R, Price D, Brightling CE, Heaney LG. Comorbidity in severe asthma requiring systemic corticosteroid therapy: cross-sectional data from the optimum patient care research database and the British thoracic difficult asthma registry. Thorax. 2016;71(4):339–46.

Panek M, Mokros L, Pietras T, Kuna P. The epidemiology of asthma and its comorbidities in Poland--health problems of patients with severe asthma as evidenced in the province of Lodz. Respir Med. 2016;112:31–8.

Varsano S. Severe and non-severe asthma in the community: a large electronic database analysis. Respir Med. 2017;123:131–9.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Cinthia Torreão and Ronan Valladares for operational support as GSK employees, and the editorial support in the form of copyediting, which was provided by Juliana Reyes of RANDOM LTD and was funded by GSK.

Funding

This study (PRJ2544) was funded by GSK. GSK contributed to the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CS contributed to study design and conception, data analysis and interpretation; HN contributed to data analysis and interpretation; FM contributed to study design and conception, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation; KV contributed to study design and conception, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation; VDB contributed to study design and conception, data analysis and interpretation; GL contributed to study design and conception, data analysis and interpretation; CV contributed to acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation; GA contributed to data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to manuscript development and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is a reanalysis of a previously conducted study – the Asthma Control in Latin America (ASLA) study – with no additional data collection. The previous ASLA study was approved by applicable institutional review boards/independent ethics committees and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All institutional review boards/independent ethics committees have been listed in the Additional file 1. Prior to study participation, all patients aged 18 years or older provided written informed consent; patients aged 12 to 18 years provided a written assent form, and their parents or legal guardians (for emancipated minors) provided written informed consent, in accordance with local requirements.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

HN has nothing to disclosure; KV and FM are GSK employees; CV and GA are GSK complementary employees. CS, GL and VDB are GSK employees and holds GSK stocks.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Ethics Committees. All institutional review boards/independent ethics committees. (DOCX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Neffen, H., Moraes, F., Viana, K. et al. Asthma severity in four countries of Latin America. BMC Pulm Med 19, 123 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-019-0871-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-019-0871-1