Abstract

Background

Despite the progress seen in the last decade in diagnosis and treatment, lung cancer has still a bad prognosis and a substantial number of patients died within the weeks following diagnosis. The objective of this study was to quantify early mortality in lung cancer, to identify patients who are at high risk of early decease, and to describe their management in a real world.

Methods

Prospective observational study including consecutively all adult patients managed for primary lung cancer histologically or cytologically diagnosed in 2010 in the respiratory medicine department of one of the participating French general hospitals. Patients and cancer characteristics and first therapeutic strategy were collected at diagnosis. Dates of death were obtained from investigators or town council of the patient’s birth place. All fatal cases were considered regardless of the cause of the death. Multivariate logistic regression model was used to determine the factors significantly and independently associated with death at 1 and 3 months.

Results

Seven thousand fifty-one patients from 104 centres were included in the study. Vital status was obtained for 6,981 patients. Respectively, 678 (9.7 %) and 1,621 (23.2 %) of the 6,981 patients with available data died within 1 and 3 months following diagnosis. As compared with the other patients, they were significantly older and frailer (based on performance status [PS] and recent weight loss) and more frequently reported stage IV tumour. Overall, 64.5 % (1 month) and 42.8 % (3 months) of patients had no cancer therapy and less than 1 % were included in a therapeutic trial.

Conclusion

About one in four patients died within 3 months following lung cancer diagnosis. Early mortality mainly involves frail patients with advanced cancer and is associated with lack of cancer therapy. This supports the need for early diagnosis and clinical trials in this population. Reducing early mortality to give supplementary time to patients to organise the future is a major challenge for 21st century physicians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Despite the progress seen in the last decade in diagnosis and treatment, lung cancer has still a bad prognosis [1]. In France, in 2010, 1-year mortality rate in patients with lung cancer was estimated at 56 % [2].

Literature on lung cancer mortality is abundant. Between 01-January-2000 and 30-November-2015, more than 8,000 articles with an abstract could be identified when consulting PubMed with the following sentence: ‘lung neoplasms [Mesh]’ and ‘mortality [Mesh]’. However, available information about early mortality is limited [3]. Most of the literature relates to treatment and usually excludes elderly, frail, and socially marginalised patients [3], or tries to identify predictors of early mortality after specific therapeutic interventions (e.g., surgical resection) or in specific populations (e.g., patients with comorbidity).

In 2010, the French College of General Hospital Respiratory Physicians (CPHG) conducted a prospective observational study, KBP-2010-CPHG, whose main objective was to assess 5-year mortality rate. This study involved the respiratory medicine department of 119 French general hospitals. Overall, 7,610 adults managed with primary lung cancer histologically or cytologically diagnosed between the 01-January-2010 and 31-December-2010 in the participating respiratory medicine departments were included [4].

As a significant proportion of patients from the KBP-2010-CPHG died just after the diagnosis of lung cancer, a post hoc analysis was performed to (a) quantify early mortality (1 and 3 months), (b) to identify the main characteristics of patients who early died, and (c) to describe their management. From health care system and professional perspectives, identifying patients who early died and describing their management emphasize the need for earlier diagnosis and palliative approaches and for more effective treatment. From a patient or family perspectives, they emphasize the need for more effective treatment and improved support to save time and better face this unfavourable outcome [5].

Methods

KBP-2010-CPHG is a French prospective multicentre observational study. The study protocol was approved by the advisory committee on research information processing in the health field (CCTIRS) on 19 November 2009 and the French Information technology and freedoms commission (CNIL) on 11 January 2010 (909479). The ethics committee of the French Speaking Society of Pneumology confirmed the observational nature of the study on 23 April 2010 (N°2010-008). All included patients were duly informed of the study objectives and requirements, and gave their oral consent before inclusion.

At the end of 2009, the members of the CPHG which gathers the chest physicians of the respiratory departments of the French general hospitals (overseas departments and territories included) were contacted. Those agreeing to participate became study investigators and their respiratory medicine department a study centre. Each investigator has to exhaustively include all patients aged over 18 years managed in his/her respiratory medicine department for a primary lung cancer histological or cytological diagnosed with a sample collected between 1st January and 31st December 2010. The date of sample was considered to be the date of the diagnosis. Then, the investigator filled out an anonymous questionnaire comprising items on the patient, his/her tumour, and its treatment really performed. A steering committee assessed study compliance [4, 6]. Vital status and date of death were obtained by the investigator or town council of the patient’s birth place at least 1-year after the date of diagnosis.

All fatal cases were considered regardless of the cause of the death. Patients who were alive 1 and 3 months after the diagnosis date were censured at this date. First, data were described using mean and standard deviation (mean [SD]) or frequency and percentage (number [%]). At 1 and 3 months, Chi2-test or Fisher test (when Chi2-test criteria were not respected) and Student t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) (for normal distributions) or non-parametric tests (for non-normal distributions) were used to compare died and alive patients in univariate analyses. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to determine the factors significantly and independently associated with death at 1 and 3 months. Statistical test results were considered significant at p < 0.05 (2-sided). Missing data were not replaced.

Results

Study follow-up and baseline characteristics of the study population

A total of 119 respiratory medicine departments participated in the study and included 7,610 patients. Fifteen (15) centres deemed to be non-exhaustive by the steering committee were excluded from the study analysis. In addition, some patients were excluded from the study as they presented with major protocol failures: i.e., no information on histological or cytological sampling, sampling date outside of the recommended window, primary lung cancer not confirmed at histology, or cancer managed outside of the study centre. Finally, the KBP-2010-CPHG analysis population included 7,051 patients (including 6,083 patients with non-small-cell lung cancer [NSCLC]) from 104 centres.

Mortality rates within the 1st year following diagnosis

The vital status at 1 year and the date of death (for died patients) were obtained for 6,981 patients. Respectively, 678 (9.7 %) and 1,621 (23.2 %) patients died within 1 and 3 months following diagnosis.

Characteristics of the patients according to their vital status at 1 and 3 months

Main characteristics of patients according to their vital status 1 and 3 months following diagnosis are presented in Table 1.

Compared with other patients, patients who early died were older (p < 0.001), although 7 (9.6 %) and 12 (16.4 %) of the 73 patients aged 40 years or less died within 1 and 3 months following diagnosis, respectively.

Patients who early died were leaner than the other patients (p < 0.001) and had more frequently lost weight within the 3 months preceding the diagnosis (p < 0.001). Of the 616 patients having lost 10 kg or more, 115 (18.7 %) and 269 (43.7 %) died within 1 and 3 months.

Compared with other patients, patients who early died more frequently had a poorer performance status (PS ≥ 2) (p < 0.001).

No significant differences was observed between early dead patients and other patients in smoking status (p = 0.831 and p = 0.803 at 1 and 3 months, respectively), but among smokers (former or active), heavier consumer tended to die prematurely (p = 0.003 and p < 0.001, respectively).

Characteristics of the tumours according to patient’s vital status at 1 and 3 months

Table 2 presents the main characteristics of the tumour according to patients’ vital status 1 and 3 months following diagnosis.

Compared with other patients, patients who early died more frequently had small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) at 1 month (19.5 % versus 13.2 %, p < 0.001; mortality rate: 13.7 %) but not at 3 months (14.6 % versus 13.5 %, p < 0.001; mortality rate: 24.6 %). Compared with other patients with NSCLC, patients who early died more frequently had large-cell carcinoma at 1 month (17.9 % versus 10.6 %, p < 0.001; mortality rate: 15.4 %) and at 3 months (10.2 % versus 14.9 %, p < 0.001; mortality rate: 30.8 %). They less frequently had adenocarcinoma, squamous-cell carcinoma, or other lung cancer.

EGFR-mutation tests were performed for 2,111 patients, mainly patients who did not early died (p < 0.0001). When explored, EGFR-mutation was less frequently reported in early died patients than in the other patients (p = 0.058 at 1 month and p = 0.003 at 3 months). The tumour of 6 (3.0 %) and 23 (11.4 %) of the 202 explored patients died within 1 and 3 months following diagnosis carried the EGFR mutation.

Stage IV tumour was more frequent in patients who early died than in the other patients. Respectively, 29 (2.6 %) and 73 (6.5 %) of the 1,129 patients with lung cancer of stage IIB and over died within 1 and 3 months following diagnosis.

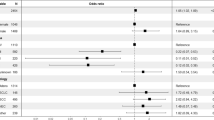

Independent risk factors of early death

Multivariate analysis (Table 3) confirmed that impaired performance status (PS > 0) (PS4: OR = 71.9 [41–130.28], p < 0.001, at 1 month and OR = 44.23 [26.29–77.66], p < 0.001, at 3 months), advanced cancer (OR = 2.17 [1.24–3.88], p = 0.008 and OR = 2.36 [1.49-3.92], p < 0.001, at 1 month and OR = 2.44 [1.68–3.56], p < 0.001 and OR = 3.66 [2.72–5.02], p < 0.001, at 3 months, for stage IIIB and stage IV, respectively), weight loss within the 3 months preceding diagnosis (OR = 1.4 [1.09–1.81, p < 0.01 at 1 month and OR = 1.54 [1.3–1.82], p < 0.001 at 3 months), and large-cell carcinoma (OR = 1.72 [1.23–2.38], p = 0.001, at 1 month and OR = 1.33 [1.04–1.68], p = 0.022, at 3 months) were independent risk-factors of 1 and 3-month mortality. Small-cell carcinoma was an independent risk-factor of mortality at 1 month (OR = 1.39 [1.03–1.87], p = 0.032) but a protective-factor at 3 months (OR = 0.73 [0.58–0.92], p = 0.008). Finally, multivariate analysis showed that female gender (OR = 0.69 [0.52–0.9], p = 0.007) was an independent protective-factor of 1-month mortality and old age (>70 years) (OR = 1.51 [95 % CI: 1.11–2.08], p = 0.011) an independent risk-factor of 3-month mortality.

Characteristics of the first therapeutic strategy according to patient’s vital status and in dead patients at 1 and 3 months

Table 4 presents the main characteristics of the first therapeutic strategy according to patients’ vital status at 1 and 3 months after diagnosis.

Compared with the other patients, patients who early died less frequently received at least 1 cancer therapy (curative surgery incl.) (p < 0.001). At least 1 cancer treatment was prescribed in 35.5 % of patients who died within 1 month and 57.2 % of patients who died within 3 months. Overall 14 patients who early (0.9 %) died were included in a clinical trial. The first therapeutic strategy was less frequently discussed during a multidisciplinary meeting in patients who early died than in the other patients (p < 0.001).

In patients who early died, radiofrequency was exceptional (≤0.2 %) and curative surgery rare (≤3 %). Radiotherapy was infrequent (9.7 % and 18.5 % of patients who died within 1 and 3 months, respectively) and quasi-exclusively palliative (e.g., treatment of cerebral metastasis). Patients with radiotherapy who died within 1 or 3 months had virtually no curative radiotherapy (0.0 and 0.6 %). Respectively, 27.6 % and 44.5 % of patients who died within 1 and 3 months received chemotherapy. Chemotherapy was palliative in almost all patients (97.3 % and 97.9 %, respectively), and only 71 patients received a targeted therapy. Respectively, 49.3 % and 35.9 % of patients who died within 1 and 3 months received supportive care.

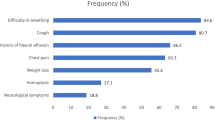

Characteristics of patients without cancer therapy

Of the 951 patients without cancer therapy, respectively, 437 (46.0 %) and 693 (72.9 %) were dead 1 and 3 months after the diagnosis. The percentage of patients who received no cancer therapy increased with increasing age, PS, and tumour stage (Fig. 1).

The main characteristics of the 951 patients without cancer treatment are presented in Table 5 according to vital status at 1 and 3 months.

Compared with the other patients with no cancer therapy, patients who early died were significantly younger (p < 0.001), they more frequently reported recent weight loss (p < 0.001), and more frequently reported a PS of 3 or 4 (p < 0.001). Respectively, 107 (82.3 %) and 130 (90.9 %) of the 143 patients with PS4 died within 1 and 3 months. Patients who early died more frequently had a small-cell carcinoma and less frequently presented with squamous-cell carcinoma (p < 0.001) than the other patients with no cancer therapy. They also more frequently had a stage IV tumour: respectively, 318 (54.5 %) and 549 (84.0 %) of the 653 patients with stage IV tumour died within 1 and 3 months. The percentage of patients who early died rose with PS and tumour stage increase but not with age increase.

Discussion

The results of this study showed that in 2010, in France, about 1 to 10 patients managed for primary lung cancer in the respiratory department of a general hospital died within 1 month and about 1 to 4 died within 3 months after lung cancer diagnosis. They also showed that patients who died within 1 or 3 months following lung cancer diagnosis were older and frailer (based on PS and weight loss before diagnosis) than the other patients and more frequently had a lung cancer at advanced stage. Finally, they pointed out that most of these patients had no cancer therapy and most of patients without cancer therapy early died.

Quantification of early death

To the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the first aimed to evaluate the percentage of patients with lung cancer who early died in clinical practice regardless of their characteristics (e.g., age, PS) and tumour stage. It shows that a significant proportion of patients died within 1 (9.7 %) or 3 months (23.2 %) following diagnosis. In the comparable KBP-2000-CPHG study, performed 10 years ago in French general hospitals, the 3-month mortality was very close (22.1 %) indicating the lack of improvement in 10 years. However, 3-month mortality rate in our study was lower than that recently reported by O’Dowd et al. in UK [3], 30 %. The 3-month mortality among patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer who developed respiratory failure was also reported in a retrospective study and was very high in this population (94.4 %) [5].

Main characteristics of patients who early died

Univariate analyses showed that patients who early died had greater PS, lower BMI, and greater recent weight loss than the other patients. Patients also more frequently reported stage III or IV cancer. Age, sex, PS, histology type, and cancer stage were included in the 4-year mortality score developed and validated in 2006 using data from KBP-2000-CPHG study [7].

In the present study, we included recent weight loss. In the literature, weight loss (>10 %) is a well-known bad prognostic factor [8, 9]. Our results tended to indicate that weight loss was a risk factor of early death and also possibly a warning factor.

Early mortality did not seem to depend on sex and was poorly associated with histology type. Small-cell carcinoma was an independent risk-factor of mortality at 1 month but a protective-factor at 3 months. This apparent discrepancy possibly reflects the good initial response to chemotherapy of small-cell lung cancers [10]. All in all, the most important parameter in early mortality is probably the cancer therapy that is actually performed, in particular chemotherapy, and PS at diagnosis which determines treatment [11, 12].

In the recent UK study by O’Dowd et al. [3], high rate of pre-diagnosis consultations, social deprivation and rural residence are associated factors with early death. These indicators were not registered in our study.

Patients who early died usually did not receive cancer therapy

Most of the patients who early died did not receive any specific cancer therapy, especially the oldest. Patients who early died more frequently had tumour at advanced stage and non-operable status. They get less curative treatment (surgery, radiofrequency, radiotherapy) and more palliative treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy). Despite the French National Cancer Institute developed in 2010 a national program for mutation screening in lung cancer giving us result in 7 days (4 to 25 days), this population get less mutation screening and targeted therapy prescribed. Also, clinical trial access was lower. However, these patients benefits from a multidisciplinary meeting discussion as well as the others. The youngest patients get more than the oldest a cancer treatment.

Probably because patients were old and had a higher PS (3 or 4), clinicians are helpless. Treatment options cannot easily be used in such patients in particular when they presented with stage III or IV cancer. The decrease in the percentage of patients with cancer therapy with increasing age, PS, and stage confirms this hypothesis.

What would be the room for improvement?

Prevention, in particular through smoking cessation campaigns, and lung cancer screening are the keys for improving lung cancer mortality rate. Early diagnosis is the key for reducing time to diagnosis and time to treatment and, then, is for great importance to improve early mortality. It can give the patients a chance to get a systemic treatment before deterioration of the general condition (better PS, early stage tumour, less weight loss). Also, it can give the old and frail patients and their family a chance to organise the future. Therefore, physicians should pay attention to the smokers with increased respiratory symptoms and recent weight loss and, rapidly refer to a thoracic oncologist. Reducing early post-operative mortality is for need depending on the resection type (lobectomy versus pneumonectomy, sleeve lobectomy) and the team experience [13]. There is a need for clinical research or trial on the patients with bad prognostic factor (PS, tumour stage, age) and development on palliative care treatment [14]. Lung cancer mutation screening is for great importance in all stages or PSs to give access to targeted therapy even or especially in the poor prognostic population who pays a heavy price to early mortality.

Strengths and limitations

This study uses a large dataset (7,051 included patients, about 20 % of all lung cancers diagnosed in France in 2010) and gives a true reflect of the lung cancer early mortality in a real-world in France in 2010. However, this is not a registry. This study gives us a view on the management of lung cancer in the general hospital, only. But general hospitals supports about 40–45 % of lung cancer in France. The data completeness was checked as described before [6].

In this analysis, we did not separate NSCLC and SCLC which influence the mortality because we focused on the timing, not on the histology type. In fact, from the clinician point of view, the main problem is that the patient fulfils poor prognostic factors and that he/she has to improve patient’s quality of life and life expectancy.

Finally, the cause of death was unknown but lung cancer was probably the main cause regarding the short interval after diagnosis, the severity of the disease, and the low influence from smoking status. In this study, surgery is pooled with other treatments. However, curative surgery was rare in patients who early died (≤3 %). In addition, we found (data not shown) that 1- and 3-month mortality rates in operated subjects (1.4 % and 3.7 %) were lower than in non-operated subjects (11.4 % and 27.2 %), indicating that perioperative deaths do not explain early mortality. We did not have information on the metastatic site (brain) which could have an influence on the early mortality as well as the site of the palliative radiotherapy performed [12].

Conclusions

About 10 % of patients with lung cancer deceased within the month following the diagnosis (date of sampling) and 25 % within 3 months. As compared with the other patients, patients who early died were older and frailer (greater PS and recent weight loss) and more frequently presented with stage IV tumour. Also, they presented more frequently with a large-cell or small-cell carcinoma and were less EGFR mutant. Most of these patients did not receive any cancer therapy, probably because clinicians are helpless. There is a need to improve early diagnosis to give the patients a chance to receive a systemic treatment to reduce early mortality and/or to give time to the patients and his/her family to organise the future. Indeed, there is a paucity of clinical data guiding the management of clinicians due to the underrepresentation in clinical trials of old and frail patients. Specific clinical trials using new drugs (targeted therapies) or new therapeutic strategies in old and/or frail patients must be implemented.

References

Walters S, Maringe C, Coleman MP, Peake MD, Butler J, Young N, et al. Lung cancer survival and stage at diagnosis in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK: a population-based study, 2004-2007. Thorax. 2013;68(6):551–64.

Institut National du Cancer. [Some statistics]. 2014. Available at: http://www.e-cancer.fr/cancerinfo/les-cancers/cancers-du-poumon/quelques-chiffres. Accessed 30 Nov 2015.

O’Dowd EL, McKeever TM, Baldwin DR, Anwar S, Powell HA, Gibson JE, et al. What characteristics of primary care and patients are associated with early death in patients with lung cancer in the UK? Thorax. 2015;70(2):161–8.

Grivaux M, Locher C, Bombaron P, Collon T, Coëtmeur D, Dayen C, et al. [Study KBP-2010-CPHG : inclusion of new cases of primary lung cancer diagnosed in general hospital pneumology departments between 1st January and 31 December 2010. Rev Pneumol Clin. 2010;66:375–82. in French.

Medarov B, Challa TR. Short term mortality among patients with non–small cell lung cancer and respiratory failure: a retrospective study. Chest Disease Report. 2011;1(e7):14–6.

Locher C, Debieuvre D, Coëtmeur D, Goupil F, Molinier O, Collon T, et al. Major changes in lung cancer over the last ten years in France: The KBP-CPHG studies. Lung Cancer. 2013;81(1):32–8.

Blanchon F, Grivaux M, Asselain B, Lebas FX, Orlando JP, Piquet J, et al. 4-year mortality in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: development and validation of a prognostic index. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(10):829–36.

Myers J, Lata K, Chowdhury S, McAuley P, Jain N, Froelicher V. The obesity paradox and weight loss. Am J Med. 2011;124(10):924–30.

Myrskylä M, Chang VW. Weight change, initial BMI, and mortality among middle-and older-aged adults. Epidemiology. 2009;20(6):840–8.

Demedts IK, Vermaelen KY, van Meerbeeck JP. Treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung carcinoma: current status and future prospects. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(1):202–15.

Aarts MJ, van den Borne BE, Biesma B, Kloover JS, Aerts JG, Lemmens VE. Improvement in population-based survival of stage IV NSCLC due to increased use of chemotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E387–95.

Nieder C, Angelo K, Haukland E, Pawinski A. Survival after palliative radiotherapy in geriatric cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(11):6641–5.

Pezzi CM, Mallin K, Mendez AS, Greer Gay E, Putnam Jr JB. Ninety-day mortality after resection for lung cancer is nearly double 30-day mortality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148(5):2269–77.

Morere JF, Brechot JM, Westeel V, Gounant V, Lebeau B, Vaylet F, et al. Randomized phase II trial of gefitinib or gemcitabine or docetaxel chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and a performance status of 2 or 3 (IFCT 0301 study). Lung Cancer. 2010;70(3):301–7.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the members of the steering committee and all the chest physicians who have actively participated in this study (see list hereafter). They also thank Alizée Petit (kbp-2010-cphg@margauxorange.fr) and Fabienne Péretz for their help in preparing this article.

Steering committee: Michel Grivaux, Chrystèle Locher, Didier Debieuvre, Bernard Asselain, François Blanchon, Daniel Coëtmeur, Thierry Collon, Charles Dayen, François Goupil, Francis Martin, Olivier Molinier, Jacques Le Treut.

Investigators: Drs Caroline Clarot, Olivier Leleu, Abbeville; Jacques Le Treut, Aix-en-Provence; Bernard Borrel, Albi; Marie-Pierre Lafourcade, Michel Martin, Angoulême-Saint-Michel; Stephane Hominal, Annecy; Christine Mouroux-Rotomondo, Antibes-Juan-Les-Pins; Catherine Dubos-Arvis, Argentan; Hubert De Cremoux, Argenteuil; Yves Lierman, Arras; Michèle Gay, Aubagne; Patrick Dion, Aubenas; Jérôme Virally, Aulnay-sous-Bois; Hubert Barbieux, Khaldoun Hakim, Christine Lemonnier, Auxerre; Philippe Tagu, Bar-le-Duc; Jean-Claude Mouries, Bastia-Furiani; Jean-Pierre Mathieu, Cecilia Nocent-Ejnaini, Bayonne; Didier Debieuvre, Belfort-Montbéliard; Laurent Portel, Bergerac; Frédéric Goutorbe, Béziers; Pascale Beynel, Marie-Laure Braud, Marielle Perrichon, Bourg-en-Bresse; Gilles Adam, Yves-Marie Allain, Zafer Khayat, Antoine Lévy, Bourges; Béatrice Gentil le Pecq, Anne-Claire Ravel, Bourgoin-Jallieu; Bruno Remignon, Briey; Jean-Yves Le Tinier, Briis-sous-Forges-Bligny; Patricia Barre, Michel Farny, Cahors; Yannick Duval, Christophe Perrin, Cannes; Gérard Berthiot, Chalons-en-Champagne; Violaine Frappat, Eric Kelkel, Chambéry; Marguerite Le Poulain-Doubliez, Charleville-Mézières; Florence Lamotte, Chateauroux; Bernard Simon, Chaumont; Patrick Dumont, Chauny; Katy De Luca, Chevilly-Larue; Philippe Masson, Cholet; Valérie Hammerer, Didier Levy, Pierre Désiré Meyer, Lionel Moreau, Jean-Philippe Oster, Colmar; Antoine Belle, Stéphanie Dehette, Sandrine Loutski, Compiègne; Abderhamane Belmekki, Philippe Ménager, Odile Salmon, Corbeil-Essonnes; Jacky Crequit, Pierre Le Lann, Creil; Cyril Bernier, Dinan; Edith Maëtz, Jean-Yves Tavernier, Douai; Jean-Renaud Barrière, Draguignan; François Martin, Dreux; Frederic Deniel, Eaubonne; Pierre-Alexandre Hauss, Elbeuf-Louviers-Val-de-Reuil; Michel Carbonnelle, Epernay; Jean-Louis Collignon, Jean-Pierre Pontier, Epinal; Habeeb Mahmoud, Evreux; Ahmed Merzoug, Fougères; Djilalli Boudoumi, Béatrice Desurmont-Salasc, Fréjus-Saint-Raphaël; Pascal Thomas, Gap; Véronique Tizon-Couetil, Granville-Avranches; Micheline Figueredo, Grasse; Kheder Badour, Guingamp; Eric Fournier, Hénin-Beaumont; Alexandra Bedossa, Lagny-sur-Marne; David Lemerre, La Rochelle; Jacques Berruchon, La-Roche-sur-Yon; Cécile Dujon, Le-Chesnay-Versailles; Olivier Raffy, Marc Zaegel, Le-Coudray-Chartres; Marc Peureux, Le-Havre; François Goupil, Olivier Molinier, Le-Mans; Dragos Ciobanu, Lens; Oana Florea, Lens; Jean-Michel Marcos, Libourne; Gerard Oliviero, Longjumeau; Marielle Perrichon, Lons-Le-Saunier; Jean-Paul Vabre, Lourdes; Jean-Marc Dot, Jean-Michel Peloni, Lyon-Desgenettes; Anne-Sophie Blanchet-Legens, Sylvie Vuillermoz-Blas, Lyon-St-Joseph-St-Luc; Sébastien Larive, Mâcon; Jean-Bernard Auliac, Mantes-la-Jolie; Mokrane Belkaïd, Martigues; Michel Grivaux, Chrystèle Locher, Meaux; Jean-Pierre Di Mercurio, Melun; Nadine Paillot, Metz; Etienne Leroy-Terquem, Meulan-les-Mureaux; Tayeb Benaicha, Montargis; Bernard Duvert, Montélimar; Thierry Collon, Jacques Piquet, Montfermeil-Le-Raincy; Ravin Rangasamy, Mont-Saint-Martin; David Renault, Morlaix; Hamid Belhadj, André Marcuccilli, Moulins; Pierre Bombaron, Didier Debieuvre, Anne-Catherine Neidhardt, Mulhouse; Marie Saillour, Nanterre; Geoffroy De Faverges, Dominique Herman, Nevers; Isabelle Bourlaud, Michel D’Arlhac, Niort; Guillaume Fesq, Nouméa-Nouvelle-Calédonie; Eric De Groote, Oloron-Sainte-Marie; Adrien Dixmier, Bertrand Lemaire, Orléans; Geneviève Perrus, Paimpol; Pablo Ferrer-Lopez, Papeete-Tahiti; Camille Genety, Paray-le-Monial; Patrick-Aldo Renault, Pau; Serge Lacroix, Périgueux; Didier Choma, Perpignan; Gislaine Fraboulet, Pontoise; Hubert Galloux, Quimper; Sylvie Julien, Rodez; Nathalie Bautin, Florence Bolard, Anne Brichet-Martin, Béatrice Cavestri, Nicolas Just, Juliette Lelong, Fabienne Salez, François Steenhouwer, Roubaix; Daniel Coëtmeur, Guillaume Leveiller, Saint-Brieuc; Habib Benothman, Stéphane Jouveshomme, Saint-Germain-en-Laye-Poissy; Eric Goarant, Saint-Malo; Clothilde Marty, Daniel Sandron, Saint-Nazaire; Eric Huchot, Fabrice Paganin, Saint-Pierre-Réunion; Marie Boutemy, Charles Dayen, Emmanuelle Lecuyer, Saint-Quentin; Bendela Kasseyet-Kalume, Salon-de-Provence; François Brolly, Saverne; Serge Jeandeau, Sainte-Feyre; Ghassan-Jacques Kassem, Sedan; Marie-Germaine Legrand-Hougnon, Soissons; Pierre Botrus, Thionville; Philippe Romand, Thonon-Les-Bains; Bertrand Delclaux, Troyes; Philippe Brun, Robert Riou, Valence; Didier Debieuvre, Jean Pierre Gury, Vesoul; Jacques Boyer, Catherine Marichy, Vienne; Lionel Falchero, Villefranche-sur-Saône; Alain Cuguilliere, Villenave-d’Ornon; Andriamampionoma Razafindramboa, Villeneuve sur lot; Catherine Fouret, Villeneuve-Saint-Georges.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

MG, DD, DH, CL, JMM, JC, SVB, PB, MS and FM claim not to have received reimbursements, fees, funding, or salary from an organization that may in any way gain or lose financially from the publication of this manuscript, either now or in the future. They also claim not hold stocks or shares in an organization that may in any way gain or lose financially from the publication of this manuscript, either now or in the future, and to have any other financial competing interests. Finally, they claim not to have non-financial or personal relationship with other people or organization that could inappropriately bias this work.

This study was promoted by the Collège des Pneumologues des Hôpitaux Généraux (CPHG) with the help of the endowment fund Recherche en Santé Respiratoire of the CNMR and Pneumologie development, and funded by the following laboratories: AstraZeneca, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly France, Pierre Fabre Oncologie, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi-Aventis. The study sponsors were not involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, report writing, or decision to submit for publication.

Authors’ contributions

MG, DD, FM conceived the study and participated in its design and coordination. MG, DD, DH, CL, JMM, JC, SVB, PB, MS and FM participated in the study and included patients. MG, DD, DH, CL, JMM, JC, SVB, PB, MS and FM helped to draft the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Grivaux, M., Debieuvre, D., Herman, D. et al. Early mortality in lung cancer: French prospective multicentre observational study. BMC Pulm Med 16, 45 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-016-0205-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-016-0205-5