Abstract

Background

Poor mood states pose the most frequent mental health, creating a considerable burden to global public health. Sedentary behavior is an essential factor affecting mood states, however, previous measures to reduce sedentary time in Chinese young adults have focused only on increasing physical activity (PA). Sedentary, PA, and sleep make up a person’s day from the standpoint of time use. It is not known whether reallocating sedentary time to different types of PA (e.g. daily PA and structured PA) or sleep during an epidemic has an effect on mood states. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the association between replacing sedentary time with different types of PA or sleep during the pandemic and the mood states of Chinese young adults and to further examine whether this association varies across sleep populations and units of replacement time.

Method

3,579 young adults aged 18 to 25 years living in China and self-isolating at home during the COVID-19 outbreak were invited to complete an online questionnaire between February from 23 to 29, 2020. Subjects’ PA, sedentary time, and mood states were assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire and the Chinese version of the Profile of Mood States, respectively. Participants also reported sleep duration and some sociodemographic characteristics. Participants were divided into short sleepers (< 7 h/d), normal sleepers (7–9 h/d), and long sleepers (> 9 h/d) based upon their reported sleep duration. Relevant data were analyzed using Pearson correlation analysis and isotemporal substitution model (ISM).

Results

Sedentary time was negatively associated with mood states in Chinese young adults during the pandemic (r = 0.140) and correlated strongest among short sleepers (r = 0.203). Substitution of sedentary time with structured PA was associated with good mood states (β=-0.28, 95% CI: -0.49, -0.08). Additionally, substituting sedentary time with daily PA (e.g. occupational PA, household PA) was also associated with good mood states among normal sleepers (β=-0.24, 95% CI: -0.46, -0.02). The substitution of sedentary time with sleep could bring mood benefits (β=-0.35, 95% CI: -0.47, -0.23). This benefit was particularly prominent among short sleepers. Furthermore, for long sleepers, replacing sedentary time with sleep time also resulted in significant mood benefits (β=-0.41, 95% CI: -0.69, -0.12). The longer the duration of replacing sedentary behavior with different types of PA or sleep, the greater the mood benefits.

Conclusions

A reallocation of as little as 10 min/day of sedentary time to different types of PA or sleep is beneficial for the mood states of young adults. The longer the reallocation, the greater the benefit. Our results demonstrate a feasible and practical behavior alternative for improving mood states of Chinese young adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) broke out in December 2019, and spread rapidly around the world. The government has advised citizens to self-isolate at home to decrease social mobility to minimize the spread of the virus [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has stated that the COVID-19 pandemic causes a large threat to global physical and mental health [2]. A mood is a mental state and is a pervasive and sustained emotion or feeling tone, such as happiness, anger, tension, or anxiety [3]. It constitutes an essential component of daily experience and can impact one’s perceptions and interactions with the world [4]. Research studies have corroborated that a significant proportion of individuals have been highly prevalent in mood disturbances such as panic, suspicion, dysphoria, and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic [5, 6]. A recent meta-analysis found that the global prevalence of depression (25%) during the pandemic was seven times higher than the global prevalence of depression (3.44%) in 2017 [7]. Mood states concerns were reported at the highest rate in China, where the outbreak originated [8].

A person’s mood states are affected not only by the interactions between environmental and personality factors, but also by everyday activity behavior including sedentary behavior (any waking behavior with energy expenditures of ≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents while in a sitting, reclining or lying posture [9]), physical activity (PA) (any bodily movement that results in energy expenditure [10]), and sleep (a spontaneous and reversible state of rest [11]) [12, 13]. Existing evidence demonstrates that the lockdown policy during the pandemic had an unintended impact on sedentary behavior [14, 15]. The restrictions on going out and the need to work or learn at home have led to a significant increase in sedentary time for recreation and leisure and sedentary time for office study among young adults [16] Although research on the relationship between sedentary behavior and health is still in its infancy in China [17], evidence from a growing number of studies consistently suggests that sedentary behavior has a negative impact on mood states [18, 19]. To reduce the harm caused by sedentary behavior, public health guidelines recommend limiting the time spent sitting [20]. However, Time-Use Epidemiology studies have shown that the total time of the day is 24 h, where a decrease in the time spent on one activity (e.g. sedentary behavior) means an increase in the time spent on other activities (e.g. PA or sleep) [21]. Hence, when advocating for individuals to reduce sedentary behavior to gain health benefits, public health guidelines should also encompass guidance for the substitution activity for sedentary behavior.

The Isotemporal Substitution Modeling (ISM), devised by Mekary and colleagues is a simple and appropriate approach for estimating the health implications of theoretically replacing one type of activity for another with the same amount of time, while allowing for adjustments for the confounding effects of the remaining activities [22]. This model has been validated, and gained recognition within the academic community [23]. To date, only a considerable number of studies have applied this statistical approach in populations such as children and adolescents, older adults, and pregnant women. These previous studies addressed a range of health indicators such as obesity, diabetes, executive functioning, and life quality [24,25,26,27,28]. To our knowledge, there is limited research on mental health indicators in young adults using the ISM approach. A cohort study conducted in the United States involving young adults aged 21 to 35 years demonstrated that substituting sedentary behavior with PA could potentially yield psychological advantages in both the short- and longer-term [29]. It appears that daily PA (e.g., sweeping floors, cleaning windows) is more inherently accomplishable and performable than structured PA (performing the scheduled and regimented exercise, e.g., dancing, playing tai chi [30]). Studies have shown that people are more likely to engage in daily PA during the pandemic [31]. Therefore, it is effort-worthy to examine whether replacing sedentary time with daily PA is beneficial to mood states especially in COVID-19 pandemic situations. Although sleep, which occupies a large portion of the 24-hour day, has been significantly associated with mood states in previous studies [18, 19]. However, most studies using ISM do not include sleep indicators in their analyses [32], which is an important limitation. Whether replacing sedentary with sleep duration for Chinese young adults during an epidemic can provide mood benefits is still up in the air. From a public health perspective, it is consequential to find out how reallocating time from sleep to sedentary affects the mood states of young adults.

Multiple studies have demonstrated there is a U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and adverse psychological symptoms, wherein both insufficient and excessive sleep duration can precipitate mood disturbances [33, 34]. This could mean that sleep should be prioritized as a replacement for sedentary, followed by PA, for insufficient sleepers, or it could mean that replacing sedentary time with PA or sleep will not necessarily result in mood benefits for young adults who have excessive amounts of sleep. Therefore, when testing the relationship between replacing sedentary with PA or sleep and mood states, it is necessary to analyze subgroups of different sleep populations. Finally, by combing through all the studies that used ISM, it was observed that the majority of these studies commonly used predetermined units of time substitution (10, 15, 30, or 60 min), while rarely comparing the impact of different durations being allocated from one activity to another. Providing information about the impact of these different durations on mood states provides useful information that could be customized to suit different clusters of young adults who have different lifestyle behaviors.

The present study employed ISM to address the following research questions: Is there an association between sedentary time and mood states in Chinese young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic? Are there benefits to mood states when sedentary time is replaced with different types of PA or sleep time? Do these associations and substitution benefits vary among different sleep populations (e.g. short sleepers, normal sleepers, and long sleepers)? Are there differences in the benefits to mood states for different replacement times?

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

Young adults aged 18 to 25 years, residing in China and staying home in self-quarantine during the COVID-19 outbreak, were invited to partake in a questionnaire between 23 February and 29 February 2020. The implementation of China’s home quarantine policy during the pandemic has resulted in limitations on conducting face-to-face surveys. Questionnaire contents were uploaded to a freely accessible online Chinese survey platform (https://www.wjx.cn) and disseminated using snowball sampling. Upon clicking on the online questionnaire link, participants were presented with an initial interface containing an introduction to the questionnaire and were directed to indicate their consent to taking part in the survey. Upon selecting the option “Know the questionnaire content and agree to participate in the questionnaire study,” the formal content of the questionnaire was displayed. This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Hunan Normal University (approval number: 2020 − 393).

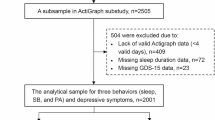

A total of 3,579 participants completed the online survey. Before data processing, we applied a series of exclusion criteria: (1) response time less than 4 min (a minimum time required to complete the questionnaire) (N = 382); (2) in a day, PA, sedentary time, or sleep duration all exceed 24 h, or these three behaviors total 24 h (N = 142); (3) zero hours spent PA, sedentary or sleeping (N = 88); (4) identical responses to the questions on the mood states (e.g., for each response, the participants selected “not at all”.) (N = 36); (5) obvious discrepancy among demographic information (e.g., the year 2000 was selected as the response to the birth year question, but the age group of 31 to 40 was chosen for the age group response.) (N = 11). Following these exclusion criteria, 2,920 questionnaires were considered valid for inclusion in the data analysis.

Measurements

Time spend on PA, sedentary, and sleep

PA and sedentary time during the COVID-19 pandemic were assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [35]. The IPAQ comprises 31 items and estimates the frequency and duration of sedentary behavior and various types of PA in the last seven days. Physical activities included four types [36]: household PA (e.g. cooking, washing clothes, mopping the floor), occupational PA (e.g., using a computer, writing), transport PA (e.g. walking, cycling), and leisure time PA (e.g. rope skipping, playing table tennis, resistance training). Based on literature recommendation [37], leisure time PA can be referred to as “structured PA”. Household PA, occupational PA, and transport PA were combined into an indicator of “daily PA”. Participants’ PA was also grouped into three types of intensity: light-intensity physical activity (LPA), moderate PA, and vigorous PA. Consistent with previous studies [38], we combined moderate and vigorous-intensity PA and renamed as moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA). The IPAQ has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity in the Chinese population [39]. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the IPAQ was 0.81.

Sleep duration was assessed using two items from a self-reported open-ended question: “What time did you usually fall asleep during the previous seven days?”, “What time did you usually wake up during the previous seven days?”. Sleep duration was calculated based on participants’ reported time of falling asleep at night and waking up in the morning [40]. Based on previous studies and the National Sleep Foundation’s recommendation of sleep duration for young adults [41, 42], we stratified participants into three groups: short sleepers (< 7 h/day), normal sleepers (7–9 h/day), and long sleepers (> 9 h/day). In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the self-reported sleep duration was 0.70.

Mood states

Mood states of participants during the COVID-19 pandemic were assessed by the Chinese version of the Profile of Mood States (POMS) which had been shown to demonstrate good reliability and validity [43, 44]. The POMS contained seven subscales: vigor, self-esteem, tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion. Participants were instructed to describe how they have been feeling in the past week. Each item was rated on a 5-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “extremely”. The total mood disturbance (TMD) score was calculated by combining the scores of five subscales for the negative mood states (tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion) and subtracting it from the score for the two positive subscales for the positive mood states (vigor, and self-esteem). Scores could range from 0 to 200, with higher scores indicating a higher degree of mood disturbance [45]. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the POMS was 0.73.

Finally, basic demographic variables such as age, gender (male and female), region (rural and urban), and body mass index (computed by participant height and body mass) were collected.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were completed using SPSS 26 and figures were produced using GraphPad Prism. Continuous variables conforming to a normal distribution were expressed as mean and standard deviation, while continuous variables not conforming to a normal distribution were expressed as median and quartiles [46]. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. P values less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) were considered statistically significant.

Pearson’s correlation was used to assess the association between sedentary time and mood states among Chinese young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The ISM was used to test the effect on mood states when replacing the amount of time in sedentary behavior with the same amount in another activity (e.g. PA or sleep) while keeping total behavior time constant [22]. First, we examined the effect of replacing sedentary time with daily PA, structured PA, or sleep on mood states, the ISM was expressed as: logit (Mood states) =(β1) daily PA+(β2) structured PA+(β3) sleep+(β4) total behavior time+(β5) covariates. The coefficients β1, β2, and β3 represented the effect of substituting an equal amount of sedentary time with daily PA, structured PA, or sleep, respectively.

Next, daily PA was categorized into occupational PA, transport PA, and household PA. Structured PA was further divided into structured LPA and structured MVPA. The effect of replacing sedentary time with these activities on mood states was examined and the ISM was expressed as: logit (Mood states) =(β1) occupational PA +(β2) transport PA +(β3) household PA +(β4) structured LPA +(β5) structured MVPA +(β6) sleep +(β7) total behavior time +(β8) covariates. The coefficients β1, β2, β3, β4, and β5 represented the effect of substituting an equal amount of sedentary time with occupational PA, transport PA, household PA, structured LPA, or structured MVPA, respectively.

As a change of activity of 10 min per day may be more easily achieved [47], a 10-minute substitution unit was chosen as the starting time interval. Thereafter, alternative units of 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 min, respectively, were used to compare differences in the mood effects of different replacement times. All models were adjusted for potential confounders, and these were age, sex, region, and body mass index.

Results

Table 1 shows that of the total participants (n = 2920), 73.7% were female, and 57.8% came from the rural regions. The average sedentary time and sleep duration among all participants were 7.8 h and 9.4 h per day, respectively. Self-reported sedentary time was highest (8.2 h/day) among short sleepers. The median daily PA time and structured PA time for all participants was 10.0 min/day and 7.1 min/day, respectively. The average score of TMD among all participants was 100.1, and a higher TMD score was found among short sleepers.

The relationship between sedentary time with mood states in Chinese young adults

Pearson correlation analysis showed a significant positive association between sedentary time and TMD scores among all participants (r = 0.140, p < 0.01) (Fig. 1.). Notably, the correlation coefficient between sedentary time and TMD scores was greatest among short sleepers (r = 0.203, p < 0.05), compared to normal sleepers (r = 0.158, p < 0.01) and long sleepers (r = 0.109, p < 0.01).

Effects of replacing sedentary behavior with different types of PA or sleep on mood states

Figure 2. shows that reallocating 10 min/day of sedentary time to an equal amount of structured PA was associated with lower TMD scores among total participants (β=-0.28, 95% CI: -0.49, -0.08), However, this substitution effect was found primarily in structured MVPA (β=-0.38, 95% CI: -0.63, -0.13). Notably, replacing 10 min/day of sedentary time with an equal amount of daily PA was also associated with lower TMD scores (β=-0.24, 95% CI: -0.46, -0.02) among normal sleepers. However, this substitution effect was found mainly in occupational PA (β=-0.60, 95% CI: -1.16, -0.05) and household PA (β=-0.35, 95% CI: -0.64, -0.06).

When substituting 10 min/day of sedentary time with an equivalent duration of sleep, significantly lower TMD scores were observed (β=-0.35, 95% CI: -0.47, -0.23). This substitution effect was greatest among short sleepers (β=-1.99, 95% CI: -2.94, -1.03). Furthermore, even among long sleepers, replacing an equivalent amount of sedentary time with 10 min/day of sleep was still linked to lower TMD scores (β=-0.41, 95% CI: -0.69, -0.12).

The coefficient β (95% confidence intervals) of TMD scores when replacing 10 min/day sedentary time with an equal amount of time of different types of PA and sleep among young adults aged 18 to 25 years during the pandemic. Notes rose-red lines represent statistical significance (p < 0.05), blue lines represent no statistical significance (p > 0.05). Higher TMD score indicates a higher degree of mood disturbance. Abbreviations PA = physical activity; LPA = light-intensity physical activity; MVPA = moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity; TMD = total mood disturbance

Differences in the benefits to mood states for different replacement times

The effects of replacing an equivalent amount of sedentary time with 10 to 60 min/day of different types of PA or sleep on TMD scores are presented in Table 2. When the substitution of sedentary time with different types of PA or sleep was statistically significant in relation to lower TMD scores, the longer the replacement time, the greater the benefit. In addition, among short sleepers, replacement of sedentary time by 20 min/day of sleep (β=-3.97) was associated with similar reduced TMD scores as compared to replacement by 30 min/day of structured PA (β=-3.98).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study with 2920 young adults aged 18 to 25 years from China aimed to investigate the independent associations between sedentary time and mood states during the COVID-19 epidemic and the effects of reallocating sedentary time to different types of PA or sleep on mood states. There was evidence of nonlinearity in the associations of sleep with mood states [33]. Thus, all outcomes were stratified by sleep duration. Our findings showed that sedentary time was positively associated with mood disturbances in Chinese young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic where the correlation was strongest among short sleepers (sleep duration < 7 h/day). Substitution of sedentary time with structured PA was associated with good mood states. Additionally, substituting sedentary time with daily PA (e.g. occupational PA, household PA) was also associated with good mood states among normal sleepers (sleep duration within 7–9 h/day). Significantly, the substitution of sedentary time with sleep could bring mood benefits. This benefit was particularly prominent among short sleepers. Furthermore, even when sleeping more than 9 h/day, replacing sedentary time with sleep time also resulted in significant mood benefits. Finally, we found that the longer the duration of replacing sedentary behavior with different types of PA or sleep, the greater were the mood benefits.

In the present study, we found that replacing sedentary time with structured PA may have provided mood benefits. This is consistent with studies conducted in Australia, which showed that a reallocation of more PA was associated with better mental well-being when replacing sedentary behavior [48]. Such findings were also observed in studies conducted in Canada [49] and Korea [50]. The observed benefits of substituting sedentary with structured PA on mood states have been explained by underlying physiological and psychological mechanisms. Engaging in structured PA can decrease the levels of stress hormones in the body, such as cortisol and adrenaline, while boosting endorphin levels, leading to a feeling of optimism and relaxation [51]. It can also increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which aids in alleviating symptoms of anxiety [52]. Moreover, it helps in establishing a sense of self-efficacy and enhancing the feeling of control over stressful situations [53]. Simultaneously, it can divert people’s attention, which releases psychological pressure and effectively reduces anxiety [54]. Currently, interventions to decrease sedentary time typically focus on increasing the time spent in MVPA, as this activity produces a greater energy expenditure. The WHO has recommended that adults partake in a minimum of 150 to 300 min of moderate-intensity or 75 to 150 min of vigorous-intensity PA per week [20]. However, meeting current recommendations on PA remains a key challenge, as evidenced by the low adherence around the globe [55]. The data from worldwide surveys showed that about a quarter to a third of the world’s young adult population is insufficiently physically active [56, 57]. In China, the proportion of young adults who have met the recommended standards of PA was even less than 45% during the COVID-19 epidemic [58]. It is accepted that to obtain appreciable health benefits from an activity, one of the first steps toward achieving it is to encourage the masses to start engaging in at least one healthy behavior, followed by sustained effort and persistence of other healthy behaviors. Only then do these behaviors culminate with of the recommended guidelines. Therefore, from a public health perspective, it is crucial to find an alternative to sedentary behavior that is participatory and accessible to the general public. Many studies have demonstrated that engaging in daily PA (e.g. housework) is readily achievable and also cost-effective [24, 59, 60]. In the current study, we found that replacing an equivalent amount of sedentary time with daily PA can lead to mood benefits in normal sleepers. Hence, it is feasible to encourage adults with adequate amounts of sleep to substitute some sedentary time with daily PA, rather than focusing exclusively on promoting structured MVPA. In the future, lifestyle interventions that target replacing some sedentary behavior with daily PA are promising research directions.

Other than PA, it was found that substituting sedentary time with sleep was also associated with lower TMD scores. With the exception of a study of adults aged 45 years carried out in the Netherlands [61], sleep has not been incorporated into the analysis using the ISM in apparently any other study in adults. In practice, a reallocation of time among different behaviors must be done with caution. When people sleep more than the guideline standard per night, reallocating sedentary time to sleep may lead to some reduction in sedentary time, but it also means that sleep time increases further beyond the recommended limit. In this case, does the substitution of additional sleep still have a positive effect? Our study has asserted that substituting sedentary time with sleep was also associated with good mood states in those who exceeded the national sleep recommendations of 7–9 h/day. This finding provides some evidence that perhaps one of the best ways to ensure better mood states during pandemics is to increase sleep time even if the recommended standards of sleep have been met. Longer sleep duration is related to reduced activity in the amygdala and increased connectivity between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex [62, 63]. Thus, increased sleep duration may reduce emotional reactivity and enhance emotion regulation abilities during the COVID-19 pandemic [64].

In previous studies, each study used only one predetermined unit of substitution time (e.g., 10 min) during analyses. Our study statistically analyzed the substitution effects of different substitution time units (from 10 to 60 min) and showed that the longer the sedentary behavior was reallocated to structured PA or sleep, the greater were the mood benefits. For example, reallocating 10–60 min from sedentary to structured PA was associated with a reduction in TMD scores of -0.28 (95%CI: -0.49, -0.08), -1.70 (95%CI: -2.93, -0.47), respectively. Furthermore, among short sleepers, replacing sedentary time with 20 min of sleep was linked to a similar reduction in TMD scores compared to replacing it with 30 min of structured PA (β=-3.97 and − 3.98, respectively). Also, substituting sedentary time with 40 min of sleep resulted in a lower TMD score (β=-7.95), and this was comparable to replacing it with 60 min of structured PA (β=-7.96). This finding highlighted that sleep as a health behavior may be more important than structured PA, especially in short sleepers. These findings are useful information for promoting better mood states.

Although research on the relationships between replacing sedentary time with PA or sleep and mental health among adults was emergent in Western countries, apparently no research had employed the use of ISM to examine these relationships among Chinese young adults in the COVID-19 pandemic. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to use the ISM to analyze the effects of replacing sedentary time with different PA or sleep on the mood states of young Chinese adults in the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings of this study contribute to a further understanding of the impact of sedentary time in young adults, and also provide useful information for the design of future interventions for reducing sedentary time (e.g. reallocating sedentary time to different types of PA or sleep).

Like all research, there are some limitations to the present study. First, this study was cross-sectional in design and, which captured only the possible associations between variables rather than providing causal interpretations. Future studies could adopt a longitudinal design and a prospective cohort design in order to further explore associations between the variables. Second, all variables were assessed using a self-reported questionnaire. The use of subjective measures like questionnaires is dependent on the participants’ recall accuracy and is limited by social desirability bias. These biases were, however, mitigated in the present research by using a 7-day recall (i.e., participants were asked to recall their activities over no more than the past 7 days) and by using an anonymous questionnaire with no identifiers collected from participants. Objective measurement tools, such as accelerometers, can be used in the future to avoid self-reporting bias and enhance the quality of the data. Third, despite efforts to control for confounders during the design and analysis phases, a lack of data on potential confounders (e.g., weather conditions [65], dietary habits [66], presence of a disease [67], presence of medication [68], presence of poor lifestyle habits [69]) may have affected the results of the study. Further studies should take these potential confounders into account. Finally, although the ISM was used in this study, it remains solely a numerical technique and cannot replace experimental evidence. Furthermore, methods for analyzing 24-hour movement behavior data including PA, sedentary, and sleep, such as compositional data analysis [70] and multivariate pattern analysis [71] are emerging and are relatively novel. Moreover, there is no definitive consensus regarding the superiority of these methods over others (e.g. standard regression) [72], for analyzing the relationships between daily 24-hour lifestyle behaviors and health in young adults.

Conclusion

Sedentary time was negatively associated with mood states among Chinese young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic, and this relationship was most pronounced in short sleepers. Replacing sedentary time with structured PA provided mood benefits; however, higher levels of structured MVPA are needed for better mood states. For normal sleepers (meeting the recommendation of 7–9 h/ day of sleep), replacing sedentary behavior with daily PA (e.g., occupational PA or household PA) may enhance mood states. Sleep may be used to replace sedentary time even when sleep has met or exceeded recommended standards. In short sleepers, a reallocation of sedentary time to sleep should be prioritized, followed by a reallocation to structured PA. Most importantly, even just reallocating 10 min/day of sedentary time to different types of PA or sleep is beneficial for the mood states of young adults. In sum, the reallocation of longer sedentary times to either sleep or PA produced better results in the mood states of young adults in the COVID-19 pandemic. From a scientific perspective, we suggest that future studies should aim to understand the perceptions and acceptability of daily lifestyle changes in young adults and further validate the effects of replacing sedentary time with different types of PA and sleep on the mood states of young adults with different sleep durations by means of longitudinal and interventional methods to provide accurate references for guideline refinement.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the first author (Dan Li, lidan97@hunnu.edu.cn), without undue reservation.

Abbreviations

- ISM:

-

Isotemporal substitution model

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- LPA:

-

Light-intensity physical activity

- MVPA:

-

Moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity

- TMD:

-

Total mood disturbance

References

Wilder-Smith A, Freedman DO. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J Travel Med. 2020;27(2):taaa020.

Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet (London England). 2020;395(10223):470–3.

Clark AV. Causes, role, and influence of Mood States. Nova; 2005.

Kaufmann C, Agalawatta N, Bell E, Malhi GS. Getting emotional about affect and mood. Australian New Z J Psychiatry. 2020;54(8):850–2.

Ammar A, Trabelsi K, Brach M, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, et al. Effects of home confinement on mental health and lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak: insights from the ECLB-COVID19 multicentre study. Biology Sport. 2021;38(1):9–21.

Terry PC, Parsons-Smith RL, Terry VR. Mood responses Associated with COVID-19 restrictions. Front Psychol. 2020;11:589598.

Bueno-Notivol J, Gracia-García P, Olaya B, Lasheras I, López-Antón R, Santabárbara J. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2021;21(1):100196.

Ahmed MZ, Ahmed O, Aibao Z, Hanbin S, Siyu L, Ahmad A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;51:102092.

Tremblay MS, Aubert S, Barnes JD, Saunders TJ, Carson V, Latimer-Cheung AE, et al. Sedentary Behaviour Research Network (SBRN) Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2017;10(14):75.

Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):126–31.

Carskadon MA, Dement WC. Normal human sleep: an overview. Principles Pract Sleep Med. 2005;4(1):13–23.

Köhler CA, Evangelou E, Stubbs B, Solmi M, Veronese N, Belbasis L, et al. Mapping risk factors for depression across the lifespan: an umbrella review of evidence from meta-analyses and mendelian randomization studies. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;103:189–207.

Pieh C, Budimir S, Probst T. The effect of age, gender, income, work, and physical activity on mental health during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown in Austria. J Psychosom Res. 2020;136:110186.

Stockwell S, Trott M, Tully M, Shin J, Barnett Y, Butler L, et al. Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviours from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: a systematic review. Bmj Open Sport Exerc Med. 2021;7(1):e000960.

Evenson KR, Alothman SA, Moore CC, Hamza MM, Rakic S, Alsukait RF, et al. A scoping review on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and sedentary behavior in Saudi Arabia. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):572.

Wilms P, Schröder J, Reer R, Scheit L. The impact of Home Office work on physical activity and sedentary behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):12344.

Chen S, Ma J, Hong J, Chen C, Yang Y, Yang Z, et al. A public health milestone: China publishes new physical activity and sedentary Behaviour guidelines. J Activity Sedentary Sleep Behav. 2022;1(1):9.

Giurgiu M, Koch ED, Ottenbacher J, Plotnikoff RC, Ebner-Priemer UW, Reichert M. Sedentary behavior in everyday life relates negatively to mood: an ambulatory assessment study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2019;29(9):1340–51.

DeMello MM, Pinto BM, Dunsiger SI, Shook RP, Burgess S, Hand GA, et al. Reciprocal relationship between sedentary behavior and mood in young adults over one-year duration. Ment Health Phys Act. 2018;14:157–62.

Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451–62.

Pedišić Ž, Dumuid D, Olds T. Integrating sleep, sedentary behaviour, and physical activity research in the emerging field of time-use epidemiology: definitions, concepts, statistical methods, theoretical framework, and future directions. Kinesiology. 2017;49(2):252–69.

Mekary RA, Willett WC, Hu FB, Ding EL. Isotemporal Substitution paradigm for physical activity epidemiology and weight change. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(4):519–27.

Martins GS, Galvão LL, Tribess S, Meneguci J, Virtuoso JS. Isotemporal substitution of sleep or sedentary behavior with physical activity in the context of frailty among older adults: a cross-sectional study. São Paulo Med J. 2022;141(1):12–9.

Sadarangani KP, Cabanas-Sánchez V, Von Oetinger A, Cristi-Montero C, Celis-Morales C, Aguilar-Farías N, et al. Substituting sedentary time with physical activity domains: an isotemporal substitution analysis in Chile. J Transp Health. 2019;14:100593.

Li X, Zhou T, Ma H, Liang Z, Fonseca VA, Qi L. Replacement of Sedentary Behavior by Various Daily-Life Physical Activities and Structured Exercises: Genetic Risk and Incident Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;dc210455.

Fairclough SJ, Tyler R, Dainty JR, Dumuid D, Richardson C, Shepstone L, et al. Cross-sectional associations between 24-hour activity behaviours and mental health indicators in children and adolescents: a compositional data analysis. J Sports Sci. 2021;39(14):1602–14.

Yasunaga A, Shibata A, Ishii K, Inoue S, Sugiyama T, Owen N, et al. Replacing sedentary time with physical activity: effects on health-related quality of life in older Japanese adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16:240.

Macgregor AP, Borghese MM, Janssen I. Is replacing time spent in 1 type of physical activity with another associated with health in children? Appl Physiol Nutr Metabolism. 2019;44(9):937–43.

Meyer JD, Ellingson LD, Buman MP, Shook RP, Hand GA, Blair SN. Current and 1-Year psychological and physical effects of replacing Sedentary Time with Time in other behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(1):12–20.

Ceria-Ulep CD, Tse AM, Serafica RC. Defining exercise in contrast to physical activity. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2011;32(7):476–8.

Gupta A, Puyat JH, Ranote H, Vila-Rodriguez F, Kazanjian A. A cross-sectional survey of activities to support mental wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disorders Rep. 2021;5:100167.

Sadarangani KP, Schuch FB, De Roia G, Martínez-Gomez D, Chávez R, Lobo P, et al. Exchanging screen for non-screen sitting time or physical activity might attenuate depression and anxiety: a cross-sectional isotemporal analysis during early pandemics in South America. J Sci Med Sport. 2023;26(6):309–15.

Jiang J, Li Y, Mao Z, Wang F, Huo W, Liu R, et al. Abnormal night sleep duration and poor sleep quality are independently and combinedly associated with elevated depressive symptoms in Chinese rural adults: Henan Rural Cohort. Sleep Med. 2020;70:71–8.

Tsou MT. Association between Sleep Duration and Health Outcome in Elderly Taiwanese. Int J Gerontol. 2011;5(4):200–5.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–95.

Hagströmer M, Oja P, Sjöström M. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrent and construct validity. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(6):755–62.

Matthews CE, Moore SC, Blair A, Xiao Q, Keadle SK, Hollenbeck A, et al. Mortality benefits for replacing sitting time with different physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(9):1833–40.

Grgic J, Dumuid D, Bengoechea EG, Shrestha N, Bauman A, Olds T, et al. Health outcomes associated with reallocations of time between sleep, sedentary behaviour, and physical activity: a systematic scoping review of isotemporal substitution studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2018;15:69.

Macfarlane D, Chan A, Cerin E. Examining the validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire, long form (IPAQ-LC). Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(3):443–50.

Leppänen MH, Ray C, Wennman H, Alexandrou C, Sääksjärvi K, Koivusilta L, et al. Compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines and the relationship with anthropometry in Finnish preschoolers: the DAGIS study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1618.

Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, Bliwise DL, Buxton OM, Buysse D, et al. Recommended amount of Sleep for a healthy adult: a Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(06):591–2.

Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. 2015;1(1):40–3.

Chen KM, Snyder M, Krichbaum K. Translation and equivalence: the Profile of Mood States short form in English and Chinese. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002;39(6):619–24.

Terry PC, Lane AM, Fogarty GJ. Construct validity of the Profile of Mood States-adolescents for use with adults. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2003;4(2):125–39.

Searight HR, Montone K. Profile of Mood States. Encyclopedia Personality Individual Differences. 2020;4057–62.

Gao C, Cai Y, Zhang K, Zhou L, Zhang Y, Zhang X, et al. Association of hypertension and antihypertensive treatment with COVID-19 mortality: a retrospective observational study. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(22):2058–66.

Ekblom-Bak E. Isotemporal substitution of sedentary time by physical activity of different intensities and bout lengths, and its associations with metabolic risk. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25(3):NP1–1.

Curtis RG, Dumuid D, Olds T, Plotnikoff R, Vandelanotte C, Ryan J, et al. The Association between Time-Use behaviors and Physical and Mental Well-being in adults: a compositional Isotemporal Substitution Analysis. J Phys Act Health. 2020;17(2):197–203.

Duncan MJ, Riazi NA, Faulkner G, Gilchrist JD, Leatherdale ST, Patte KA. The association of physical activity, sleep, and screen time with mental health in Canadian adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal isotemporal substitution analysis. Ment Health Phys Act. 2022;23:100473.

Park S, Park SY, Oh G, Yoon EJ, Oh IH. Association between Reallocation Behaviors and Subjective Health and stress in South Korean adults: an Isotemporal Substitution Model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2488.

Harber VJ, Sutton JR. Endorphins and exercise. Sports Med. 1984;1:154–71.

Huang T, Larsen KT, Ried-Larsen M, Møller NC, Andersen LB. The effects of physical activity and exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor in healthy humans: a review. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(1):1–10.

Tikac G, Unal A, Altug F. Regular exercise improves the levels of self-efficacy, self-esteem and body awareness of young adults. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 2021;62(1):157–61.

Rebar AL, Stanton R, Geard D, Short C, Duncan MJ, Vandelanotte C. A meta-meta-analysis of the effect of physical activity on depression and anxiety in non-clinical adult populations. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(3):366–78.

Varela AR, Pratt M, Powell K, Lee IM, Bauman A, Heath G, et al. Worldwide Surveillance, Policy, and Research on Physical Activity and Health: The Global Observatory for Physical Activity. J Phys Activity Health. 2017;14(9):701–9.

Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Global Health. 2018;6(10):E1077–86.

Stevens M, Rees T, Cruwys T, Olive L. Equipping physical activity leaders to facilitate Behaviour Change: an overview, call to Action, and Roadmap for Future Research. Sports Med - Open. 2022;8:33.

Qin F, Song Y, Nassis GP, Zhao L, Dong Y, Zhao C, et al. Physical activity, screen time, and Emotional Well-Being during the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):5170.

White RL, Babic MJ, Parker PD, Lubans DR, Astell-Burt T, Lonsdale C. Domain-specific physical activity and Mental Health: a Meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(5):653–66.

Ai X, Yang J, Lin Z, Wan X. Mental Health and the role of physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2021;12:759987.

Hofman A, Voortman T, Ikram MA, Luik A. Substitutions of physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep: associations with mental health in middle-aged and elderly persons. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2022;76(2):175–81.

Yoo SS, Gujar N, Hu P, Jolesz FA, Walker MP. The human emotional brain without sleep—A prefrontal amygdala disconnect. Curr Biology: CB. 2007;17(20):R877–878.

Motomura Y, Kitamura S, Nakazaki K, Oba K, Katsunuma R, Terasawa Y, et al. Recovery from unrecognized sleep loss accumulated in Daily Life Improved Mood Regulation via Prefrontal suppression of Amygdala Activity. Front Neurol. 2017;8:306.

Tempesta D, Socci V, De Gennaro L, Ferrara M. Sleep and emotional processing. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;40:183–95.

Barbosa Escobar F, Velasco C, Motoki K, Byrne DV, Wang QJ. The temperature of emotions. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0252408.

Fernández-Rodríguez R, Jiménez-López E, Garrido-Miguel M, Martínez-Ortega IA, Martínez-Vizcaíno V, Mesas AE. Does the evidence support a relationship between higher levels of nut consumption, lower risk of depression, and better mood state in the general population? A systematic review. Nutr Rev. 2022;80(10):2076–88.

Bomyea JA, Parrish EM, Paolillo EW, Filip TF, Eyler LT, Depp CA, et al. Relationships between daily mood states and real-time cognitive performance in individuals with bipolar disorder and healthy comparators: a remote ambulatory assessment study. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2021;43(8):813–24.

Fahed R, Schulz C, Klaus J, Ellinger S, Walter M, Kroemer NB. Ghrelin is associated with an elevated mood after an overnight fast in depression. medRxiv. 2023;12.

Sarris J, Thomson R, Hargraves F, Eaton M, de Manincor M, Veronese N, et al. Multiple lifestyle factors and depressed mood: a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis of the UK Biobank (N = 84,860). BMC Med. 2020;18:1–10.

Dumuid D, Stanford TE, Martin-Fernández JA, Pedišić Ž, Maher CA, Lewis LK, et al. Compositional data analysis for physical activity, sedentary time and sleep research. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;27(12):3726–38.

Aadland E, Kvalheim OM, Anderssen SA, Resaland GK, Andersen LB. Multicollinear physical activity accelerometry data and associations to cardiometabolic health: challenges, pitfalls, and potential solutions. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2019;16(1):74.

Migueles JH, Aadland E, Andersen LB, Brond JC, Chastin SF, Hansen BH, et al. GRANADA consensus on analytical approaches to assess associations with accelerometer-determined physical behaviours (physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep) in epidemiological studies. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56(7):376–84.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants involved in the survey.

Funding

The project was supported by the Science and Technology Innovative Research Team in Higher Educational Institutions of Hunan Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DL conceived the study, collected data and drafted the manuscript. XXL assisted in revising the manuscript. MC, TC, and MYC provided a critical review & co-authored the revised paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Hunan Normal University (approval number: 2020 − 393). Informed consent was obtained online. Upon initially accessing the online questionnaire link, participants were presented with the content pertaining to informed consent, granting them the option to either proceed with completing the questionnaire or terminate their involvement. We consider that they agreed to participate if they submitted the questionnaire through the link.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, D., Chua, T., Chen, M. et al. Effects of replacing sedentary time with alterations in physical activity or sleep on mood states in Chinese young adults during the pandemic. BMC Public Health 24, 2184 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19714-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19714-0