Abstract

Background

Increased consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) which have additives such as artificial colours, flavours and are usually high in salt, sugar, fats and specific preservatives, are associated with diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs). In India, there are no standard criteria for identifying UPFs using a classification system based on extent and purpose of industrial processing. Scientific literature on dietary intake of foods among Indian consumers classifies foods as unhealthy based on presence of excessive amounts of specific nutrients which makes it difficult to distinguish UPFs from other commercially available processed foods.

Methods

A literature review followed by an online grocery retailer scan for food label reading was conducted to map the types of UPFs in Indian food market and scrutinize their ingredient list for the presence of ultra-processed ingredients. All UPFs identified were randomly listed and then grouped into categories, followed by saliency analysis to understand preferred UPFs by consumers. Indian UPF categories were then finalized to inform a UPF screener.

Results

A lack of application of a uniform definition for UPFs in India was observed; hence descriptors such as junk-foods, fast-foods, ready-to-eat foods, instant-foods, processed-foods, packaged-foods, high-fat-sugar-and-salt foods were used for denoting UPFs. After initial scanning of such foods reported in literature based on standard definition of UPFs, an online grocery retailer scan of food labels for 375 brands (atleast 3 brands for each food item) confirmed 81 food items as UPFs. A range of packaged traditional recipes were also found to have UPF ingredients. Twenty three categories of UPFs were then developed and subjected to saliency analysis. Breads, chips and sugar-sweetened beverages (e.g. sodas and cold-drinks) were the most preferred UPFs while frozen ready-to-eat/cook foods (e.g. chicken nuggets and frozen kebabs) were least preferred.

Conclusion

India needs to systematically apply a food classification system and define Indian food categories based on the level of industrial processing. Mapping of UPFs is the first step towards development of a quick screener that would generate UPF consumption data to inform clear policy guidelines and regulations around UPFs and address their impact on NCDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are one of the leading causes of premature morbidity and mortality resulting in over 7 out of 10 deaths worldwide [1]. Mortality due to NCDs has been on the rise in India, increasing from 37.9% of all deaths in 1990 to 61.8% in 2016 [2, 3]. Overweight/obesity have been identified as a contributing factor [4]. The recent national-level data shows an increase of 25% in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Indian men and women over 14–15 years and 3% among children under five years [5, 6]. Due to their thin fat phenotype, Indian infants and children, who comprise almost one quarter of the total population, are predisposed to obesity [7, 8]. These risk factors are further amplified by changing food environments and behavioural variables such as tobacco, alcohol, drug use and low physical activity [9]. Exposure to unhealthy food environments in genetically predisposed children, along with other behavioural risk factors, increases their risk of developing obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases (DR-NCDs) in the long term [10].

The rapidly changing food environment is characterized by diets transitioning from minimally-processed staple foods (such as pulses and whole cereals) high in vitamins, minerals and fibre to refined, processed and ultra-processed foods (UPFs) [11]. The Indian population is exposed to a wide variety of UPFs which are hyper-palatable, packaged, convenient, affordable and have a long shelf life, such as sugar-sweetened beverages, chips, biscuits and bread, and ready-to-eat/ ready-to-cook (RTC) meals [12]. The sales data of UPFs in India demonstrates an exponential increase, from USD 0.9 billion in 2006 to USD 37.9 billion in 2019 [13]. This growth indicates a notable expansion of these food products in the market, coupled with widespread advertising efforts that specifically target vulnerable populations, including children and youth [14,15,16,17,18]. Consumer demand for UPFs has increased due to higher disposable incomes, nuclear families, single-member households, and less availability of time for housework [19, 20]. UPFs have penetrated the rural boundaries of the country and are likely making their way into households of diverse geographic and socio-economic attributes [21, 22].

The Nova food classification system categorizes foods based on the purpose and the level of processing and includes four categories: (i) unprocessed/ minimally processed foods, (ii) processed culinary ingredients, (iii) processed foods, and (iv) ultra-processed foods [23,24,25,26]. UPFs are a category of food that undergo a series of industrial processes like extrusion and moulding, and have presence of classes of additives whose function is to make the final product palatable or more appealing, such as flavours, flavour enhancers, colours, emulsifiers, thickeners, sweeteners, etc. Although not unique to UPF, they also include additives that prolong the product duration and protect original properties or prevent proliferation of microorganisms [23,24,25,26]. In addition to this, several of these products are high in saturated fats or trans-fats, added sugars, and salt and low in dietary fibre, various micronutrients and other bioactive compounds [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

Overconsumption of UPFs has been associated with higher body mass index (BMI), obesity, type-2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and certain types of cancers [36,37,38]. Given the diversity in UPFs, there is a need to systematically map the range of UPFs accessed by the Indian population. This is an important first step to understanding their potential role in contributing to the NCD burden in India and in developing strategies to encourage the substitution of the most frequently consumed UPFs to healthier alternatives. Identifying specific UPF categories could also help inform the development of dietary assessment instruments like food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) and screeners.

Methods

The present study aimed at: (i) mapping the specific categories of UPFs accessed and consumed in India, (ii) assessing the ingredient composition of these products, (iii) ranking the UPFs by consumer preference, and (iv) developing a list of categories of UPFs commonly consumed in India. For this, a secondary review of available literature complemented by an online grocery retailer scan and a saliency analysis were conducted between April 2021 and February 2022 (Fig. 1).

Step 1. The literature review was conducted to map and identify the various types of UPFs accessed, consumed, preferred and/ or purchased (as reported behaviours) in India. This review included published cross-sectional and observational research studies that used surveys, focus group discussions and interviews to elicit reported behaviours across different population groups and regions in India. International and national survey reports on UPF food intake and purchase among Indian population were also included in the review. Articles for review were identified from two electronic databases (NLM NCBI and Google Scholar). To ensure the search captured the diversity of UPFs, search terms included proxy descriptors identified in Indian policy documents [39,40,41,42,43,44], including: junk food*, fast food*, modern food*, westernized food*, ultra-processed food*, UPF*, convenience food*, ready-to-eat food*, ready-to-eat snack*, ready-to-cook food*, instant food*, frozen food*, canned food*, tinned food*, processed food*, packaged food*, high fat, sugar and salt food* and HFSS*. The literature search and data extraction was conducted by two authors (MS and GK).

To be eligible for the review, studies needed to: (i) include UPFs or their proxy descriptors, with examples of products, (ii) be conducted in either rural and/or urban areas of India, (iii) be published in the English language, between January 2012 and December 2022. This time frame was chosen to capture the high growth in UPFs sales during this decade [45, 46]. Review articles, and publications that did not define the food category studied or did not cite any examples of foods were excluded.

Data from eligible articles were extracted in MS-Excel to record key variables on UPFs or their proxy descriptors with examples, location of the study (national/specific state), geographical area (urban/rural), sample size, sampling method, study participants’ age (years) and dietary data collection tools such as 24 h dietary recalls, FFQ, interviews and structured questionnaires (Additional file 1). A free list of UPF foods and beverages identified from the reviewed studies, was developed.

Step 2. An online grocery retailer scan for extracting detailed information on the UPFs identified in Step 1, was also conducted. The objective was to review and scrutinize the ingredient list provided in the food labels and to confirm that the food item qualified as UPFs. For this online scan, three researchers (GK, IKB, MS) reviewed the online grocery websites of the largest grocery retailers in India - Big Basket, Grofers, and Amazon [47]. Individual foods and beverages from Step 1, were checked for their ingredient composition and the presence of additives. This activity was guided by the FAO document ‘Ultra-processed foods, diet quality, and health using the Nova classification system’ [23,24,25,26] and the expertise of the co-authors (NK and FHML). Food items were specifically scrutinized for the use of additives (flavours, flavour enhancers, colours, emulsifiers, emulsifying salts, artificial sweeteners, thickeners, foaming, anti-foaming, bulking, carbonating, gelling and glazing agents), specific ingredients such as industrially derived sugars (fructose, invert sugar, maltodextrin, dextrose, lactose, high fructose corn syrup, fruit juice concentrates), modified oils (hydrogenated fats, interesterified fats), extracted proteins (hydrolysed proteins, soy protein isolate, gluten, casein, whey protein, mechanically separated meat) [23,24,25,26, 48]. All food items were assessed for at least three different brands and if a majority of the items (2 out of 3) qualified as UPFs, the product category was confirmed as UPF. The free-list of UPFs identified from the literature and confirmed through label reading using the online grocery retailer scan were then categorized on the basis of the primary ingredient of their composition and/or functionality of the product. A 23 category UPF list was developed at the end of Step 2.

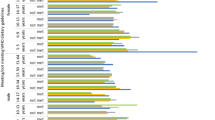

Step 3. The confirmed UPF categories (23 categories), were then subjected to a saliency analysis, conducted by two authors (GK, MS). Saliency is a statistical accounting of items for rank and frequency of mention, across all respondents within a given domain. For example, the colour chosen most often from a free list of ten colours by a study population is referred to as the most salient [49]. The saliency test indicators included the commonly accessed, consumed, preferred and/or purchased (collectively referred to as ‘preferred’ in this paper to identify the common UPF categories accessed by the Indian consumers). These categories were limited to the food items that were confirmed as UPFs in Step 2. For example, if a study used “junk food” as a descriptor of UPFs and included freshly prepared savouries like “samosa/kachori” along with chips and soft drinks, we included data for only chips and soft drinks for the purpose of saliency analysis. The UPFs were then sorted from the most to the least preferred UPFs (Additional file 2). The steps and formulas [49] used to calculate composite salience scores for each UPF category have been illustrated in Fig. 2. The UPF categories were classified per consumer preference, to the composite salience score cut-offs, defined after dividing the distribution of the composite salience scores obtained into tertiles as follows: (i) ≥ 0.61 as frequently preferred, (ii) 0.61 − 0.51 as infrequently preferred, and (iii) < 0.51 as rarely preferred UPFs.

Results

The literature search and study selection process of Step 1 is illustrated in Fig. 3. A total of 23 research articles that matched the inclusion criteria were included in the final review. An overview of the extracted variables is provided in Additional File 1. These studies were conducted in both rural (5 out of 23) and urban areas (17 out of 23), in different regions of the country, among a diverse population aged between 9 and 69 years (Table 1). Table 2 provides the outcome of the literature review with proxy descriptors along with the food items listed under them. These foods were verified as UPFs and non-UPFs.

The online grocery retailer scan, label readings of 375 packaged foods were completed (atleast 3 brands per product) and 81 of those food products qualified as UPFs. Several of the packaged Indian traditional foods and snacks such as bottled and packaged pickles, namkeens (cereal and pulse-based extruded snacks), papads, frozen non-vegetarian meals and snacks, and frozen RTE meals (like rajmah curry and rice, biryani, dal makhni, etc.) had UPF ingredients and additives in their formulation that qualified them as UPFs (Table 3). Food products such as RTE breakfast cereals (e.g. poha, upma, etc.), RTE Indian curries (e.g. paneer makhani, butter chicken, etc.), Indian RTE bread (e.g. thepla, paratha, etc.), RTC mixes (e.g. idli mix, dal vada mix, etc.) also qualified as UPFs. However, some RTE traditional meals such as RTE biryani, RTE rajmah curry with rice, RTE kadhi pakoda with rice were not categorized as UPFs as these did not include UPF ingredients.

Consumer preferences for the confirmed UPF food categories identified above, were assessed using saliency scores. Table 4 lists these categories and shows the order of preference based on the saliency scores. The last column in the table indicates ‘frequently’, ‘infrequently’ or ‘rarely’ preferred UPFs by consumers in India. The frequently preferred UPFs were breads, chips and other extruded snacks (such as potato chips, cheese balls, puff corns, etc.) and sugar-sweetened beverages (such as cold drinks, diet coke, sodas, and energy drinks. The three rarely preferred UPFs were margarine and frozen/ packaged vegetarian and non-vegetarian snacks and meals (such as stuffed/plain parantha, naan, palak paneer, rajma, cutlets, fish/seafood snacks, salami, and sausages).

Discussion

The present study aimed to identify the specific categories of UPFs accessed in India and rank them by consumer preference using a literature review, an online grocery retailer scan and saliency analysis. We found 23 categories of UPFs accessed by Indian consumers. After analysing the ingredient list of UPFs, we found that product formulation of several traditional Indian foods has transitioned from being processed to ultra-processed category with the use of industrially processed ingredients and presence of additives such as artificial colours, flavour enhancers, anti-caking agents. These ultra-processed versions of traditional foods even though have similar nutrient composition to home-prepared meals, are increasingly consumed, displacing home-cooked meals, and substituting staples. While the health effects of this displacement from minimally processed food ingredients to UPFs is an area of on-going research, we have growing evidence that UPF dietary patterns are linked to poor health outcomes [23, 69]. It is crucial to track reformulation of traditional recipes to ultra-processed convenience foods especially since traditional meals are thought to be healthier [70]. The increasing market of ultra-processed traditional Indian recipes with poor nutritional profile needs more scrutiny and research.

Saliency analysis identified the preferred UPFs among the Indian population with breads, chips and sugar-sweetened beverages being the most preferred UPFs and frozen non-vegetarian snacks being the least preferred. This finding is consistent with the sales trends reported by Euromonitor International in 2020, which has also highlighted a substantial contribution of similar categories of packaged foods, such as bakery items, biscuits, packaged dairy products, savory snacks, and sauces and condiments [46]. Further, saliency analysis also indicates the preference of Indian consumers towards UPFs such as fruit-based preserves, cookies and biscuits, Indian sweet mixes, sauces and pickles, instant noodles/soups/ pasta and savoury puff rolls. Studies from other low and middle-income countries (LMICs) demonstrates similar trends in preference (consumption of UPFs and contribution to percentage of total calories) towards packaged confectioneries, savoury snacks, deep-fried foods, biscuits, candy/ chocolate, savoury snacks, canned red and luncheon meats, pre-fried French fries, mayonnaise, ketchup, fast-food such as sandwiches and pizzas, chips and salty snacks (including tortillas and pretzels), sweets and sweetened beverages and sausages (including canned) [71, 72].

Our results also suggest a benefit of utilizing a classification system based on processing. Currently several UPFs are being captured by proxy descriptors like junk foods, fast foods, convenience foods, instant foods, packaged foods, etc. This limits comparability with other studies, monitoring the preference for and consumption of these products by the population, developing targeted interventions, tracking product reformulation and other regulatory measures to control exposure of these foods to vulnerable age groups through food advertising, etc. [73]. Using UPFs more consistently in studies reporting unhealthy food consumption pattern in India will help with global comparisons and in also elucidating the health effects of these foods. Additionally, as per the packaged food sales data from 2015-19, the Indian UPF market is slowly expanding with increasing sales of RTE meals, savoury snacks, processed fruits, vegetables, meats and other packaged foods [46]. The Nova food classification system can serve this purpose and may be explored as an option for categorization of foods by regulatory authorities. This classification system is used to assess dietary patterns in several high and middle-income countries [23, 70]. Food based dietary guidelines of several countries such as Brazil, Uruguay, Ecuador, Peru and Israel have utilized Nova classification system to inform their dietary recommendations [74,75,76,77,78].

The present paper identified only a limited number of Indian studies which were primarily reported from 2 geographical regions. More such surveys on the consumption of UPFs are desirable to identify common regional UPFs. In the Indian context, several UPFs are indigenously produced by local retailers apart from the huge market share of nationally known branded UPFs [79]. These locally accessible UPFs have greater penetration into the local markets.

The categories of UPFs in India developed in the present study after due validation can be developed into a UPF consumption screener. This tool can be used for monitoring the UPF consumption in India and can address critical gap in scientific literature. This information on quantitative estimate of UPF consumption among Indian population can be useful for assessing impact of UPF consumption on increasing burden of NCDs in India.

Strengths

This study is one of the first attempts to explore the types of UPFs in the Indian food market, identify the types of packaged traditional recipes that have been converted to UPFs, and map their saliency.

Study limitations

Studies reviewed were majorly from South India and largely represented the urban population, hence the results cannot be extended to the rural population. The study could only conduct saliency mapping of preferred foods without quantity of intake of UPFs and their contribution to total day’s energy intake. We could not explore traditional variants of UPFs that may be sold in the local unregulated markets.

Conclusions

India needs to develop a food classification system while systematically defining food categories based on level of processing. This should be followed by an assessment of the extent of UPFs consumption in India. The mapping of the UPFs in India reported in this paper provides the first step in developing a quick screener that systematically lists all the UPF categories. The data generated on consumption of UPFs using the screener is likely to inform policies on regulating the Indian UPFs market, undertake consumer education initiatives and create nutrition literacy around UPFs and thus contain their indiscriminate consumption. This may address the impact of UPF consumption on increasing burden of NCDs in India. There is an urgent need for strengthening the food regulatory environment to check the infiltration of several unhealthy UPFs in the Indian food market.

Data availability

No new data was created or analyzed under the literature review part of the study. The datasets used as part of a particular component is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- UPFs:

-

Ultra-processed foods

- NCDs:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- DR-NCDs:

-

Diet-related non-communicable diseases

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaires

- HFSS:

-

High fat sugar salt

- LMICs:

-

Low and middle-income countries

- RTE:

-

Ready-to-eat

- RTC:

-

Ready-to-cook

References

World Health Organization. Non-Communicable Diseases Country Profiles 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274512. [Cited 18 January 2023].

World Health Organization. Non-Communicable Diseases Progress Monitor 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/353048. [Cited 18 January 2023].

Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI) and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). India: Health of the Nation’s States-The Indian State-level Disease Burden Initiative. New Delhi: ICMR, PHFI, and IHME; 2017). https://phfi.org/downloads/171110_India_Health_of_Nation_states_Report_2017.pdf [Cited 20 January 2023].

Alwan A. Global status report on non-communicable diseases 2010. World Health Organization, 2011. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44579/9789240686458_eng.pdf. [Cited 8 May 2023].

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), India, 2019-21: Mizoram. Mumbai: IIPS. 2021. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00ZBN4.pdf. [Cited 18 January 2023].

Sethi V, Lahiri A, Bhanot A, Kumar A, Chopra M, Mishra R, Alambusha R, Agrawal P, Johnston R, de Wagt A. Adolescents, diets and Nutrition: growing well in a changing World, the Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey. Thematic Rep, (1), 2019.

D’Angelo S, Yajnik CS, Kumaran K, Joglekar C, Lubree H, Crozier SR et al. Body size and body composition: a comparison of children in India and the UK through infancy and early childhood. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015 July 16;69(12):1147.

India - Sample Registration System (SRS)-Statistical Report. 2020. https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/44376. [Cited 18 January 2023].

Dandona L, Dandona R, Kumar GA, Shukla DK, Paul VK, Balakrishnan K, et al. Nations within a nation: variations in epidemiological transition across the States of India, 1990–2016 in the global burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2017;390(10111):2437–60.

Tak M, Law C, Green R, Shankar B, Cornelsen L. Processed foods purchase profiles in urban India in 2013 and 2016: a cluster and multivariate analysis. BMJ open. 2022;12(10):e062254.

Baker P, Friel S. Processed foods and the nutrition transition: evidence from Asia. Obes Rev. 2014;15(7):564–77.

Dunford EK, Farrand C, Huffman MD, Raj TS, Shahid M, Ni Mhurchu C, Neal B, Johnson C. Availability, healthiness, and price of packaged and unpackaged foods in India: a cross-sectional study. Nutr Health. 2022;28(4):571–9.

The growth of ultra-processed foods in India: an analysis of trends, issues and policy recommendations. New Delhi: World Health Organization, Country Office for India; 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290210672

Bassi S, Bahl D, Arora M, Tullu FT, Dudeja S, Gupta R. Food environment in and around schools and colleges of Delhi and National Capital Region (NCR) in India. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–3.

Harris J, Heard A, Schwartz M. Older but still vulnerable: all children need protection from unhealthy food marketing. Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity. 2014; www.uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/Protecting_Older_Children_3_14.pdf. [Cited 24 December 2022].

Euromonitor International. (2019). Euromonitor International; London. Passport Global Market Information Database. https://www.euromonitor.com/

Pandav C, Smith Taillie L, Miles DR, Hollingsworth BA, Popkin BM. The WHO South-East Asia region nutrient profile model is quite appropriate for India: an exploration of 31,516 food products. Nutrients. 2021;13(8):2799.

The growth of ultra-processed foods in India: an analysis of trends, issues and policy recommendations. New Delhi: World Health Organization, Country Office for India; 2023.

Monteiro CA, Moubarac JC, Cannon G, Ng SW, Popkin B. Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes Rev. 2013;14:21–8.

Magalhães V, Severo M, Correia D, Torres D, de Miranda RC, Rauber F, Levy R, Rodrigues S, Lopes C. Associated factors to the consumption of ultra-processed foods and its relation with dietary sources in Portugal. J Nutritional Sci. 2021;10.

Prakash J. Consumption trends of processed foods among rural population selected from South India. Int J Food Nutr Sci. 2015;2(6):1–6.

Gupta A, Kapil U, Singh G. Consumption of junk foods by school-aged children in rural Himachal Pradesh, India. Indian J Public Health. 2018;62(1):65.

Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Lawrence M, da Costa Louzada ML, Pereira Machado P. Ultra-processed foods, diet quality, and health using the NOVA classification system. Rome: FAO; 2019. p. 48.

Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB, Moubarac JC, Louzada ML, Rauber F, Khandpur N, Cediel G, Neri D, Martinez-Steele E, Baraldi LG. Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(5):936–41.

Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy R, Moubarac J-C, Jaime P, Martins AP, et al. NOVA: the star shines bright. World Nutr. 2016;7(1–3):28–38.

Monteiro CA, Levy RB, Claro RM, Castro IRR, Cannon G. A new classification of foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing. Cad Saude Publica. 2010;26:2039–49. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2010001100005.

Moubarac JC, Batal M, Louzada ML, Steele EM, Monteiro CA. Consumption of ultra-processed foods predicts diet quality in Canada. Appetite. 2017;108:512–20.

Rauber F, Louzada ML, Steele EM, Millett C, Monteiro CA, Levy RB. Ultra-processed food consumption and chronic non-communicable diseases-related dietary nutrient profile in the UK (2008–2014). Nutrients. 2018;10(5):587.

da Costa Louzada ML, Ricardo CZ, Steele EM, Levy RB, Cannon G, Monteiro CA. The share of ultra-processed foods determines the overall nutritional quality of diets in Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(1):94–102.

Louzada ML, Martins AP, Canella DS, Baraldi LG, Levy RB, Claro RM, Moubarac JC, Cannon G, Monteiro CA. Impact of ultra-processed foods on micronutrient content in the Brazilian diet. Rev Saude Publica. 2015;49.

Louzada ML, Martins AP, Canella DS, Baraldi LG, Levy RB, Claro RM, Moubarac JC, Cannon G, Monteiro CA. Ultra-processed foods and the nutritional dietary profile in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2015;49.

Monteiro CA, Levy RB, Claro RM, de Castro IR, Cannon G. Increasing consumption of ultra-processed foods and likely impact on human health: evidence from Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(1):5–13.

Moubarac JC, Martins AP, Claro RM, Levy RB, Cannon G, Monteiro CA. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and likely impact on human health. Evidence from Canada. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(12):2240–8.

Poti JM, Mendez MA, Ng SW, Popkin BM. Is the degree of food processing and convenience linked with the nutritional quality of foods purchased by US households? Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(6):1251–62.

Luiten CM, Steenhuis IH, Eyles H, Mhurchu CN, Waterlander WE. Ultra-processed foods have the worst nutrient profile, yet they are the most available packaged products in a sample of New Zealand supermarkets. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(3):530–8.

Beslay M, Srour B, Méjean C, Allès B, Fiolet T, Debras C, Chazelas E, Deschasaux M, Wendeu-Foyet MG, Hercberg S, Galan P. Ultra-processed food intake in association with BMI change and risk of overweight and obesity: a prospective analysis of the French NutriNet-Santé cohort. PLoS Med. 2020;17(8):e1003256.

Levy RB, Rauber F, Chang K, Louzada ML, Monteiro CA, Millett C, Vamos EP. Ultra-processed food consumption and type 2 diabetes incidence: a prospective cohort study. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(5):3608–14.

de Miranda RC, Rauber F, de Moraes MM, Afonso C, Santos C, Rodrigues S, Levy RB. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and non-communicable disease-related nutrient profile in Portuguese adults and elderly (2015–2016): the UPPER project. Br J Nutr. 2021;125(10):1177–87.

Food Safety and Standards. (Safe food and balanced diets for School Children) Regulations 2020. https://www.fssai.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/Gazette_Notification_Safe_Food_Children_07_09_2020.pdf. [Cited 12 May, 2023].

Report of Working Group on Addressing Consumption of Foods High in Fat. Salt and Sugar (HFSS) and Promotion of Healthy Snacks in Schools of India. Working Group Constituted by Ministry of Women and Child Development Government of India 2015. https://www.nipccd.nic.in/file/reports/hfss.pdf. [Cited 12 May, 2023].

What India Eats ICMR-NIN. 2020. https://www.millets.res.in/pdf/what_india_eats.pdf. [Cited 12 May, 2023].

National Programme for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases and Stroke (NPCDCS). Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Handbook for Counsellors Reducing Risk Factors for Non-Communicable Disease. 2017 Sep. https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/Handbook%20for%20Counselors%20-%20Reducing%20Risk%20Factors%20for%20NCDs_1.pdf. [Cited 12 May,2023].

Recommended Dietary Allowances and Estimated Average Requirements Nutrient Requirements for Indians. A Report of the Expert Group - Indian Council of Medical Research National Institute of Nutrition 2020. https://www.nin.res.in/RDA_Full_Report_2020.html. [Cited 12 May, 2023].

National Multi-sectoral Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Common. NCDs 2017–2022. https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/National%20Multisectoral%20Action%20Plan%20%28NMAP%29%20for%20Prevention%20and%20Control%20of%20Common%20NCDs%20%282017-22%29_1.pdf,. [Cited 12 May, 2023].

Baker P, Machado P, Santos T, Sievert K, Backholer K, Hadjikakou M, Russell C, Huse O, Bell C, Scrinis G, Worsley A. Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes Rev. 2020;21(12):e13126.

Packaged Food in India. Euromonitor Int 2020. https://www.euromonitor.com/

India Online Grocery Market Size. Report 2021–2028. Grand View Research. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/india-online-grocery-market. [Cited 12 May, 2023].

Food Safety and Standards (Food Products Standards and Food Additives) Regulations. 2011. https://www.fssai.gov.in/cms/food-safety-and-standards-regulations.php. [Cited 8 May, 2023].

Quinlan M. Considerations for collecting free-lists in the field: examples from ethobotany. Field Methods. 2005;17(3):219–34.

Jain A, Mathur P. Intake of ultra-processed foods among adolescents from low-and middle-income families in Delhi. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57(8):712–4.

National Non-communicable Disease Monitoring Survey (NNMS 2017-18), Bengaluru ICMR-NCDIR. India. 2021. Available from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/viewer.html?Pdfurl = https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ncdirindia.org%2Fnnms%2Fresources%2fchapter_4_2_3.pdf&clen = 181451&chunk = true. [Cited 18 Jan, 2023]

Law C, Green R, Kadiyala S, Shankar B, Knai C, Brown KA, Dangour AD, Cornelsen L. Purchase trends of processed foods and beverages in urban India. Global Food Secur. 2019;23:191.

Goel S, Kaur T, Gupta M. Increasing proclivity for junk food among overweight adolescent girls in district Kurukshetra, India. Int Res J Biol Sci. 2013;16:17.

Bhavani V, Prabhavathy Devi N. Junk and Sink: A Comparative Study on Junk Food Intake among Students of India’. Shanlax Int J Arts Sci Humanit. 2020:13–8.

Naveenkumar D, Parameshwari S. A study on junk food consumption and its Effect on adolescents in Thiruvannamalai District, Tamil Nadu, India. Adalya J August. 2019;8(8):781–93. [ISSN 1301–2746].

Hiregoudar V, Suresh CM, Singode C, Raghavendra B. Proportion, patterns, and determinants of junk food consumption among adolescent students. Annals Community Health. 2021;9(2):46.

Kumari R, Kumari M. Quality aspects of fast foods and their consumption pattern among teenagers of rural-urban region of Sabour block in Bhagalpur district of India. The Pharma Innovation Journal. 2020. 2020;9(4):96–102.

Amin T, Choudhary N, Jabeen AN. Study of fast food consumption pattern in India in Children aged 16–20 years. Intl J Food Ferment Technol. 2017;7(1):1–8.

Singh M, Mishra S. Fast food consumption pattern and obesity among school going (9–13 year) in Lucknow District. Int J Sci Res. 2014;3(6):1672–4.

Kotecha PV, Patel SV, Baxi RK, Mazumdar VS, Shobha M, Mehta KG, Mansi D, Ekta M. Dietary pattern of school going adolescents in urban Baroda, India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31(4):490.

Joseph N, Nelliyanil M, Rai S, YP RB, Kotian SM, Ghosh T, Singh M. Fast food consumption pattern and its association with overweight among high school boys in Mangalore city of southern India. J Clin Diagn Research: JCDR. 2015;9(5):LC13.

Prabhu NB. Examining fast-food consumption behaviour of students in Manipal University, India. Afr J Hospitality Tourism Leisure. 2015;4(2):621–30.

Khongrangjem T, Dsouza SM, Prabhu P, Dhange VB, Pari V, Ahirwar SK, Sumit K. A study to assess the knowledge and practice of fast food consumption among pre-university students in Udupi Taluk, Karnataka, India. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2018;6(4):172–5.

Landge JA, Khadkikar GD. Lifestyle and nutritional status of late adolescent in an urban area of Western Maharashtra: cross sectional study. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2020;7(8):3027.

Iyer ML, Kumar NP. A study of Breakfast habits of Urban Indian consumers. Research Journals of Economics and Business Study. Res J Econ Bus Stud. 2014;3(8):107–16. [ISSN: 2251 – 1555].

Rathi N, Riddell L, Worsley A. Food consumption patterns of adolescents aged 14–16 years in Kolkata, India. Nutr J. 2017;16(1):1–2.

Vasan M. Consumers’ preference and consumption towards instant Food products. Think India J. 2019;22(14):8333–7.

Harrell M, Medina J, Greene-Cramer B, Sharma SV, Arora M. Understanding eating behaviors of New Delhi’s Youth. J Appl Res Child. 2015;6(2):8.

Mediratta S, Ghosh S, Mathur P. Intake of ultra-processed food, dietary diversity and the risk of nutritional inadequacy among adults in India. Public Health Nutr. 2023;26(12):2849–58.

Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Moubarac JC, Levy RB, Louzada MLC, Jaime PC. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2017;21(1):5–17.

Islam MR, Rahman SM, Rahman MM, Pervin J, Rahman A, Ekström EC. Gender and socio-economic stratification of ultra-processed and deep-fried food consumption among rural adolescents: a cross-sectional study from Bangladesh. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(7):e0272275.

Pries AM, Filteau S, Ferguson EL. Snack food and beverage consumption and young child nutrition in low-and middle‐income countries: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:e12729.

Costa CD, Faria FR, Gabe KT, Sattamini IF, Khandpur N, Leite FH, Steele EM, Louzada ML, Levy RB, Monteiro CA. Nova score for the consumption of ultra-processed foods: description and performance evaluation in Brazil. Rev Saúde Pública. 2021;55:13.

Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Moubarac JC, Martins AP, Martins CA, Garzillo J, Canella DS, Baraldi LG, Barciotte M, Louzada ML, Levy RB, Claro RM, Jaime PC. Dietary guidelines to nourish humanity and the planet in the twenty-first century. A blueprint from Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(13):2311–22. Epub 2015 Jul 24. PMID: 26205679; PMCID: PMC10271430.

Ministerio, de Salud. Guía Alimentaria para la Población Uruguay. 2016. https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-salud-publica/sites/ministerio-salud-publica/files/documentos/campanas/MSP_GUIA_ALIMENTARIA_POBLACION.pdf

Ministerio de Salud Pública del Ecuador y la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura. Documento Técnico De las Guías Alimentarias Basadas en Alimentos (GABA) Del Ecuador. Quito. 2020. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca9928es.

Ministerio de Salud Instituto Nacional de Salud y Centro Nacional de Alimentación y Nutrición. Guías Alimentarias para la Población Peruana. 2020. https://repositorio.ins.gob.pe/bitstream/handle/20.500.14196/1247/Gu%c3%ada-alimen21.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Nutritional Recommendations: The Israeli Ministry of Health. 2019. https://www.health.gov.il/PublicationsFiles/dietary%20guidelines%20EN.pdf

Downs SM, Thow AM, Ghosh-Jerath S, Leeder SR. Developing interventions to reduce consumption of unhealthy fat in the food retail environment: a case study of India. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2014;9(2):210–29.

Acknowledgements

We would like to appreciate the contribution of Dr. Shukrani Shinde for supporting the study team during the literature search and online grocery retailer scan.

Funding

This work is funded through the Innovative Methods and Metrics for Agriculture and Nutrition Action (IMMANA) programme (Grant IMMANA 3.06), led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). IMMANA is co-funded with UK Aid from the UK government and by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. This work was supported, in part, by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation [INV-002962 / OPP1211308]. Under the grant conditions of the Foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the Author Accepted Manuscript version that might arise from this submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceptualized by KSR, SGJ, NK and FHML. The literature review and online grocery retailer scan were conducted by MS, GK, IKB. The first draft of the manuscript was prepared by MS, GK, IKB, SK and SGJ. The manuscript was critiqued and edited by SGJ, NK, FHML and KSR. SGJ had primary responsibility for final content; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving humans were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at the Public Health Foundation of India, and the ethics committee of University of Sao Paulo. The current manuscript, however, reports findings from an exhaustive literature review and online grocery retailer scan for which informed consent process is not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghosh-Jerath, S., Khandpur, N., Kumar, G. et al. Mapping ultra-processed foods (UPFs) in India: a formative research study. BMC Public Health 24, 2212 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19624-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19624-1