Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly increased the risk of burnout among frontline nurses. However, the prevalence of burnout and its associated factors in the post-pandemic era remain unclear. This research aims to investigate burnout prevalence among frontline nurses in the post-pandemic period and pinpoint associated determinants in China.

Methods

From April to July 2023, a cross-sectional study was carried out across multiple centers, focusing on frontline nurses who had been actively involved in the COVID-19 pandemic. The data collection was done via an online platform. The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey was utilized to evaluate symptoms of burnout. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to pinpoint factors associated with burnout.

Results

Of the 2210 frontline nurses who participated, 75.38% scored over the cut-off for burnout. Multivariable logistic regression revealed that factors like being female [odds ratio (OR) = 0.41, 95%CI = 0.29–0.58] and exercising 1–2 times weekly[OR = 0.53, 95%CI = 0.42–0.67] were protective factors against burnout. Conversely, having 10 or more night shifts per month[OR = 1.99, 95%CI = 1.39–2.84], holding a master’s degree or higher[OR = 2.86, 95% CI = 1.59–5.15], poor health status[OR = 2.43, 95% CI = 1.93–3.08] and [OR = 2.82, 95%CI = 1.80–4.43], under virus infection[OR = 7.12, 95%CI = 2.10-24.17], and elevated work-related stress[OR = 1.53, 95% CI = 1.17-2.00] were all associated with an elevated risk of burnout.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that post-pandemic burnout among frontline nurses is influenced by several factors, including gender, monthly night shift frequency, academic qualifications, weekly exercise frequency, health condition, and viral infection history. These insights can inform interventions aimed at safeguarding the mental well-being of frontline nurses in the post-pandemic period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nurse burnout is a well-documented work-related stress syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment [1]. Research from 2012 indicated a heightened prevalence of burnout among frontline nurses [2], which is consistent with the results of a study conducted in 2018 [3]. Various factors, including exposure to violence [4], excessive workload [5], Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder [6] and insomnia [7], contribute to this phenomenon. The implications of nurse burnout are profound, potentially leading to a decline in the quality of patient care [8]. The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated the issue of nurse burnout [9, 10]. During the pandemic, elevated stress levels and exposure to traumatic events were notably correlated with an increased risk of burnout in frontline nurses [11,12,13,14]. In addition, poor staffing ratios are a significant concern, with research indicating that a nurse-to-patient ratio exceeding 1:2 amplifies the risk of burnout for nurses in intensive care units [15, 16]. The epidemic has led to a surge in burnout among frontline nurses, thereby increasing the probability of unfavorable nursing incidents.

Although factors contributing to nurse burnout were extensively studied during the pandemic, the post-epidemic prevalence and determinants of burnout among frontline nurses remain unclear. This study aims to ascertain the prevalence and underlying causes of burnout among frontline nurses in China in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted between April and July 2023, subsequent to the COVID-19 pandemic in China. The study population comprised frontline nurses holding valid professional qualification certificates. Descriptive characteristics of the nurses were gathered via the Wenjuanxing platform (https://www.wjx.cn). Initially, we signed up for the Wenjuanxing platform and subsequently imported the questionnaire content into it. This process enabled us to obtain a link to the questionnaire. We then disseminated this link to the nurses’ mobile phones through WeChat (a widely-used social application in China with over 1 billion active users), facilitating timely completion of the survey.

Instruments and measures

The following measures and questions were collected:

-

(1)

Descriptive characteristics of nurses: This included job title, gender, employment status, monthly frequency of night shifts, qualification, age, weekly frequency of exercise, personality traits, health status, history of virus infection, economic pressures, lifestyle, work-related stress, and concerns regarding potential infection. Considering that these descriptive characteristics may be related to the burnout of frontline nurses, and these specific responses can more accurately reveal the relationship between these descriptive characteristics and the burnout of frontline nurses, they were selected for this survey. Burnout Assessment: Burnout was evaluated using the Maslach Burnout.

-

(2)

Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS), a validated instrument for assessing burnout among healthcare professionals [17,18,19]. This tool has demonstrated correlations with the quality of care [20]. Comprising 22 items, respondents rate each on a 7-point scale, from 0 (Never) to 6 (Every day). The scale evaluates three domains: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal achievement. Cut-off scores of > 26, >9, and < 33 are indicative of clinically significant emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal achievement, respectively [21]. Being at high risk of burnout in at least one of the three domains is deemed as experiencing burnout [22]. The Cronbach’s α for the Chinese version of the MBI-HSS stood at 0.830 [23], signifying a substantial degree of internal consistency.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 and GraphPad Prism 9.0 software. Frequency distributions were treated as categorical variables and compared between groups using the chi-square test. To adjust for multiple testing, the Bonferroni correction was applied, with a p-value < 0.004 (0.05/14) deemed statistically significant. Multivariate regression analyses were employed to examine the relationship between nurses’ descriptive characteristics and burnout, setting the significance threshold at p < 0.004 (0.05/14). Variables selected for the adjusted analysis encompass job title, gender, employment status, monthly frequency of night shifts, qualification, age, weekly frequency of exercise, personality trait, health status, virus infection, economic pressure, lifestyle, work pressure, and concern about potential infection.

Results

Description of nurse characteristics

A total of 2,210 nurses from 27 provinces across China participated in the survey. Of these, 41.31% held the position of nurse-in-charge, and a significant majority, 80.27%, were female. Permanent employment was reported by 31.04% of the respondents, while 45.02% undertook between 5 and 10 night shifts monthly. The predominant age bracket was 25 to 36 years, encompassing 51.99% of the participants, and 66.20% held an undergraduate degree with with a specialisation. More nurses’ characteristics are provided in Table 1. The distribution of risk factors related to nurse burnout across the entire sample is detailed in Table 2.

Burnout prevalence and associated risk factors

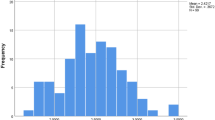

The prevalence of burnout among frontline nurses in this study was 75.38% (1,666 out of 2,210). The regression analysis concerning nurses’ descriptive characteristics is illustrated in Fig. 1. After adjusting for multiple testing (as seen in Table 3), factors like being female and exercising 1–2 times weekly were found to be protective against burnout. Conversely, having five or more night shifts monthly, holding a master’s degree or higher, poor health status, under virus infection, and elevated work-related stress were all associated with an elevated risk of burnout.

Discussion

This study evaluated burnout and its associative factors among frontline nurses after the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings pinpointed several determinants linked to burnout in frontline nurses, including gender, monthly frequency of night shifts, qualification, weekly exercise frequency, health status, and history of viral infection. Along with our study, an increasing body of research has pinpointed factors that affect the risk of burnout among nurses in the post-pandemic era. These studies can offer valuable insights for interventions aimed at mitigating nurse burnout after the pandemic [24].

Regular exercise can effectively curb the incidence of occupational burnout among oncologists [25]. Our research indicates that after the COVID-19 pandemic, 75.38% of nurses experienced burnout symptoms, encompassing emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal achievement. These results is consistent with a survey undertaken in China during the pandemic [12] but are notably higher than findings from other countries [26,27,28,29]. Several factors might account for this discrepancy: Primarily, variations in the work environment and the specific phase of the pandemic play pivotal roles in these divergent outcomes. Additionally, some studies that exclusively gauge burnout by assessing emotional exhaustion tend to report a lower prevalence. Lastly, the use of different assessment instruments can also introduce variability in results. Moreover, the readiness of health systems, potential understaffing in health organisations, workload, and other organisational factors also significantly contribute to this discrepancy.

Our research indicates that gender plays a role in burnout among frontline nurses, with females showing a lower prevalence compared to males. This observation aligns with certain previous studies [30, 31]. Another significant factor associated with burnout identified in this study is the frequency of night shifts per month. Specifically, nurses working more than 10 night shifts monthly are at a considerably heightened risk of burnout. Understaffing could be the primary cause for the increased frequency of night shifts observed among certain nurses. This correlation between the number of night shifts and elevated MBI scores is supported by earlier findings [32, 33]. Furthermore, our study discerned a link between burnout and educational qualifications. Interestingly, nurses possessing graduate degrees appear more susceptible to burnout, a trend previously observed among medical educators [34]. The primary reason that nurses with advanced educational qualifications are more susceptible to burnout is due to their excessive workload, coupled with the additional responsibility of conducting scientific research, a requirement not typically imposed on nurses with lower education levels.

Our research indicates that engaging in moderate exercise (once to twice a week) post-epidemic can considerably reduce burnout risk among frontline nurses, corroborating the outcomes of a recent study [35]. Intriguingly, we did not identify a direct correlation between extremely high or low exercise frequencies and burnout prevalence. While several reports highlight a strong relationship between poor health status and burnout [36, 37], our findings align with these, though another study detected no impact of health status on the Maslach Burnout total score [38]. The discrepancy across studies might stem from geographical differences in research areas. Notably, our comprehensive survey spanned 27 provinces and exclusively focused on frontline nurses, unlike other studies. In our study, a nurse’s viral infection status emerged as a critical factor linked to burnout. Understandably, frontline nurses infected with the virus often grapple with compromised health, amplifying their burnout risk. This aligns with our earlier observation regarding the association between poor health and increased burnout risk. Furthermore, job-related stress was identified as a burnout risk, echoing another study’s findings [39]. Interestingly, a prior study demonstrated that health-related quality of life, another measure of personal health, exhibited a strong correlation with burnout [40]. Nevertheless, further investigations are essential to validate these insights.

Although our multicenter study rigorously assessed the associations between various factors and post-pandemic burnout among frontline nurses, there are several limitations to consider: (1) Our research focused solely on China, potentially not capturing the unique experiences and mental health trajectories of frontline nurses in other cultural or national contexts; (2) Although we endeavored to encompass a diverse sample across multiple provinces, disparities in healthcare settings, the pandemic’s impact, and socioeconomic nuances across these regions might impede the wider applicability of our findings; (3) Even though we adjusted for numerous demographic elements, potential unaccounted confounders might still sway the identified correlations between burnout and the variables examined; (4) In certain provinces, the sample sizes were comparatively limited, which could potentially introduce bias into the outcomes; (5) Some descriptive characteristics of nurses (weekly frequency of exercise, personality traits, health status) were self-reported.

Conclusion

Our research reveals a higher prevalence of burnout among frontline nurses in the post-COVID-19 epidemic era. We identified several influencing factors, including gender, monthly night shift frequency, educational qualification, weekly exercise frequency, health status, and viral infection status. These insights are invaluable for strategizing interventions to manage and alleviate burnout among frontline nurses in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the results of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease

- MBI-HSS:

-

Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey

References

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory consulting psychologists. 1996.

Vandenbroeck S, Van Gerven E, De Witte H, et al. Burnout in Belgian physicians and nurses. Occup Med. 2017;67:546–54.

Molina-Praena J, Ramirez-Baena L, Gómez-Urquiza JL, et al. Levels of burnout and risk factors in medical area nurses: a meta-analytic study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:2800.

Giménez Lozano JM, Martínez Ramón JP, Morales Rodríguez FM. Doctors and nurses: a systematic review of the risk and protective factors in workplace violence and burnout. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1–19.

Biff D, Pires DEP, Forte ECN, et al. Nurses’ workload: lights and shadows in the family health strategy. Ciênc saúde Coletiva. 2020;25:147–58.

Fateminia A, Hasanvand S, Goudarzi F, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder among frontline nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic and its relationship with occupational burnout. Iran J Psychiatry. 2022;17(4):436–45.

Noh EY, Park YH, Chai YJ, et al. Frontline nurses’ burnout and its associated factors during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Appl Nurs Res. 2022;67:151622.

Garcia CL, Abreu LC, Ramos JLS, et al. Influence of burnout on patient safety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina. 2019;55:553.

Morgantini LA, Naha U, Wang H, et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid turnaround global survey. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0238217.

Denning M, Goh ET, Tan B et al. Determinants of burnout and other aspects of psychological wellbeing in healthcare workers during the covid-19 pandemic: a multinational cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0238666.

Guixia L, Hui Z. A study on burnout of nurses in the period of COVID-19. Psychol Behav Sci. 2020;9:31.

Hu D, Kong Y, Li W, et al. Frontline nurses’ burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear statuses and their associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China: a largescale cross-sectional study. EClinical Med. 2020;24:100424.

LeClaire M, Poplau S, Linzer M et al. Compromised integrity, burnout, and intent to leave the job in critical care nurses and physicians. Crit care Explorations. 2022;4:e0629.

Moradi Y, Baghaei R, Hosseingholipour K, et al. Challenges experienced by ICU nurses throughout the provision of care for COVID-19 patients: a qualitative study. J Nurs Adm Manag. 2021;29:1159–68.

Torre M, Santos Popper MC, Bergesio A. Burnout prevalence in intensive care nurses in Argentina. Enfermería Intensiva (English Edition). 2019;30:108–15.

Bruyneel A, Smith P, Tack J, Pirson M. Prevalence of burnout risk and factors associated with burnout risk among ICU nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak in French speaking Belgium. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;65:103059.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory manual. 4th ed. Menlo Park, CA: Mind Garden; 2016.

Poghosyan L, Aiken LH, Sloane DM. Factor structure of the Maslach burnout inventory: an analysis of data from large scale cross-sectional surveys of nurses from eight countries. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:894–902.

Greenglass ER, Burke RJ, Fiksenbaum L. Workload and burnout in nurses. J Community Appl Social Psychol. 2001;11:211–5.

White KM, Dulko D, DiPietro B. The effect of burnout on quality of care using Donabedian’s framework. Nurs Clin North Am. 2022;57:115–30.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP et al. Maslach burnout inventory manual, general survey, human services survey, educators survey ad scoring guides. Menlo Park, CA Mind Garden. 1986.

Bruyneel A, Bouckaert N, de Maertens C, et al. Association of burnout and intention-to-leave the profession with work environment: a nationwide cross-sectional study among Belgian intensive care nurses after two years of pandemic. Int J Nurs Stud. 2023;137:104385.

Sun H, Zhang T, Wang X, et al. The occupational burnout among medical staff with high workloads after the COVID-19 and its association with anxiety and depression. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1270634.

Galanis P, Moisoglou I, Katsiroumpa A, et al. Increased job burnout and reduced job satisfaction for nurses compared to other healthcare workers after the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Rep. 2023;13(3):1090–100.

Vinnikov D, Romanova Z, Ussatayeva G, et al. Occupational burnout in oncologists in Kazakhstan. Occup Med (Lond). 2021;71(8):375–80.

Nantsupawat A, Wichaikhum OA, Abhicharttibutra K, et al. The relationship between nurse burnout, missed nursing care, and care quality following COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32:5076–83.

Sexton JB, Adair KC, Proulx J, et al. Emotional exhaustion among US health care workers before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2232748.

Keith C, Trevor M, Julie S, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on the well-being of the UK nursing and midwifery workforce during the first pandemic wave: a longitudinal survey study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;127:104155.

Mavrovounis G, Mavrovouni D, Mermiri M, et al. Watch out for burnout in COVID-19: a Greek health care personnel study. Inquiry. 2022;59:469580221097829.

Aydin Sayilan A, Kulakaç N, Uzun S. Burnout levels and sleep quality of COVID-19 heroes. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;57:1231–6.

Giusti EM, Pedroli E, D’Aniello GE, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on health professionals: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1684.

Embriaco N, Azoulay E, Barrau K, et al. High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:686–92.

Demir A, Ulusoy M, Ulusoy MF. Investigation of factors influencing burnout levels in the professional and private lives of nurses. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003;40:807–27.

Akram Z, Sethi A, Khan AM, et al. Assessment of burnout and associated factors among medical educators. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2021;37:827–32.

Boucher VG, Haight BL, Hives BA, et al. Effects of 12 weeks of at-home, application-based exercise on health care workers’ depressive symptoms, burnout, and absenteeism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;9:e232706.

Tsou MT. Association of 5-item brief symptom rating scale scores and health status ratings with burnout among healthcare workers. Sci Rep. 2022;12:7122.

Youssef D, Abboud E, Abou-Abbas L, et al. Prevalence and correlates of burnout among Lebanese health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2022;15:102.

Peng S, Zhang J, Liu X, et al. Job burnout and its influencing factors in Chinese medical staffs under China’s prevention and control strategy for the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:284.

Liu S, Zhang Y, Liu Y, et al. The resilience of emergency and critical care nurses: a qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1226703.

Vinnikov D, Dushpanova A, Kodasbaev A, et al. Occupational burnout and lifestyle in Kazakhstan cardiologists. Arch Public Health. 2019;77:13.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all nurses for their time and cooperation in the survey.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.L. and S.W. conceived and designed the study. X.D. wrote the first draft. M.Z. and G.S. critically revised the first draft. Z.L., F.W., X.M., F.Y., L.Z. and Shuo.W. conducted data extraction, initial analysis and supervised data analysis. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Anding Hospital(reference number: 2021322079). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Their agreement to participate was asserted by choosing the “I agree” option ahead of flling the questionnaires, which confrmed their agreement to participate in the survey. All the procedures were performed in accordance with the national guidelines on research ethics and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., Luo, G., Ding, X. et al. Factors associated with burnout among frontline nurses in the post-COVID-19 epidemic era: a multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 24, 688 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18223-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18223-4