Abstract

Background

Persistent disparities exist between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (the Indigenous peoples of Australia) and non-Indigenous Australians associated with cancer, with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experiencing a longer time to treatment, higher morbidity rates, and higher mortality rates. This systematic review aimed to investigate findings and recommendations in the literature about the experiences and supportive care needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer in Australia.

Methods

A qualitative systematic review was conducted using thematic analysis. Database searches were conducted in CINAHL, Informit, MEDLINE, ProQuest, Scopus, and Web of Science for articles published between January 2000 and December 2021. There were 91 included studies which were appraised using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. The included studies reported on the experiences of cancer and supportive care needs in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations.

Results

Six key themes were determined: Culture, family, and community; cancer outcomes; psychological distress; access to health care; cancer education and awareness; and lack of appropriate data. Culture was seen as a potential facilitator to achieving optimal cancer care, with included studies highlighting the need for culturally safe cancer services and the routine collection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status in healthcare settings.

Conclusion

Future work should capitalize on these findings by encouraging the integration of culture in healthcare settings to increase treatment completion and provide a positive experience for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (Indigenous) populations of Australia experience higher rates of both cancer morbidity and mortality than the non-Indigenous population in Australia [1]. This is consistent with similar findings of worse health outcomes for Indigenous populations from Canada, America, and New Zealand among others [2]. Improving health outcomes experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should be a priority for both government and non-government organizations [3, 4]. However, there needs to be an awareness of the cultural values of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations when designing interventions, services, and programs to improve cancer outcomes, and to narrow the disparity gap [4].

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, health is more than a physical domain, recognizing the interplay between the physical, emotional, social, spiritual, and cultural elements that influence a person’s health [5]. Some factors that influence how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples may experience a cancer journey include their cultural values, differences in health literacy, discrimination based on race or socioeconomic status, communication differences, and geographic isolation [6], all of which may impact on health care access and treatment. In a recent report from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [3], over one-third of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people reported that they did not access health services when they needed them due to cultural reasons such as the lack of cultural appropriateness of the service; while one in five Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people reported racial discrimination by a healthcare professional in 2019–20 [3]. As a result, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are five times more likely than non-Indigenous people to discharge themselves from hospital earlier than recommended [3]. To combat this, there is an increasing number of services, including Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs), which offer culturally respectful cancer services such as bush medicine and traditional healing, alongside Western services, to support engagement and access to optimize health outcomes [7].

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are more likely to be exposed to risky health behaviors as a result of systemic racism and substantial socioeconomic disadvantage which will affect health decisions and behaviors [8]. These risky health behaviors include increased tobacco use, increased alcohol use, lower levels of physical activity, and poorer diet than non-Indigenous peoples [9, 10]. They are also less likely to engage in regular cancer screening programs than non-Indigenous peoples, which can lead to later diagnosis, and thereby worse cancer outcomes. In 2018–19, just 26% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women over the age of 40 presented for a mammogram, compared to 35% of non-Indigenous women. Similarly, only 40% of eligible Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females had participated in the national cervical screening program, compared to a participation rate of 68% in the total population [10, 11]. Only 21% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were invited to complete a bowel cancer screening test in 2016–17, had done so by June 2018, as opposed to 43.3% of non-Indigenous people [12]. Work is underway to optimize participation in these screening programs to align with the preferences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people such as widespread promotion of self-collection for cervical screening, and culturally specific communications used to promote participation in the bowel cancer screening program [13,14,15,16].

Despite the significant disparities experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, to the best knowledge of the authors, no comprehensive review of the literature has been undertaken to understand Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ experiences and supportive care needs relating to cancer. A rigorous systematic review is needed to inform future health policy to improve these disparities. To address this, we aimed to conduct a thematic review of the literature on the experiences and supportive care needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer in Australia. This review does not intend to focus on the diagnostic, prognostic or treatment processes associated with cancer beyond their experiential outcomes.

NB: This article most frequently uses the term ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ for Australia’s Indigenous peoples. However, some examined studies use the term ‘Aboriginal’ or ‘Indigenous’ which will be maintained if used by the original authors.

Methods

The concept for this systematic review was developed and led by A/Prof John Gilroy and Dr. Mandy Henningham, with support from the Cancer Council Australia Cancer Control Policy team. John Gilroy is a Yuin man from the NSW South Coast and is a Professor of Sociology in Indigenous Health, specializing primarily in disability studies. John is passionate about Aboriginal-owned and driven research to influence policy. Mandy Henningham is an Indigenous woman living on Dharug country in NSW. Mandy is a lecturer at the University of Sydney where they are a dedicated LGBTIQA + advocate and researcher in sexuality, sexual health, Indigenous studies, Intersex studies, youth, and mental health in the Department of Sociology and Social Policy. They bring a multidisciplinary lens to their projects which gives greater insights into the lived experiences of marginalized populations.

The Cancer Council Australia Cancer Control Policy team (DM, JM, AM, KW, MV and TB) bring a multi-disciplinary lens to this work with strong backgrounds in healthcare policy production across the cancer continuum from prevention to survivorship and end-of-life care.

This review employs systematic reviewing methods drawn from the Joanna Briggs Institute for the literature search and is reported against the 2020 PRISMA guidelines where appropriate. We have used a qualitative thematic approach for data analysis and synthesis. The protocol for the study was published on the Cancer Council website and is available here: https://www.cancer.org.au/assets/pdf/aboriginal-cancer-care-system

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

This systematic review included peer-reviewed scientific studies related to the experiences and supportive care needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and cancer. Six databases were used for the searches as per the research protocol: CINAHL, Informit, MEDLINE, ProQuest, Scopus, and Web of Science. Further grey literature searches were conducted through Google Scholar. Searches were carried out in January 2022. Included studies were published between January 2000 and December 2021, and were required to have been published in English. Broad search terms used included “cancer”, “neoplasms”, “Australia”, “Indigenous”, and “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander”, with further details of the search strategy found in Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for peer-reviewed literature required the research to have involved or have detailed any Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population and to have assessed outcomes related to a cancer diagnosis including experiences and/or supportive care needs. Studies detailing original qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods research on primary or secondary data were included. Opinion pieces, viewpoints, perspectives, invited comments, and case studies were excluded from this review. Research that was focused solely on diagnostic, prognostic or treatment processes associated with cancer was also excluded. Grey-literature was assessed against the same inclusion criteria.

Screening and study selection

Articles were imported directly into Covidence for removal of duplicates. Title and abstract screening was conducted independently by two researchers (JG, FN) using the same software. Selected studies were full-text reviewed by three researchers together (JG, MH, FN) and then imported into Endnote for reference management. All conflicts were resolved by the two lead researchers (JG, MH) through discussion.

Data synthesis

Data charting was completed for all included studies according to the following criteria: authors, year of publication, title, peer review status, aims, methods, data source, participants, and key findings.

Further to this data charting, a qualitative thematic analysis of the text of the included studies was conducted between February and June 2022, using the reflexive thematic analysis process developed by Braun and Clarke [17]. Coding was completed by three researchers (JG, MH, FN) using NVIVO, and codes and key themes were defined inductively.

Data quality appraisal

The appraisal was conducted by three researchers (JG, MH, FN) using the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (version 2018) due to its ability to appraise multiple methodologies [18]. A further check of the appraisal was conducted by two researchers to ensure validity (DM, JM).

Results

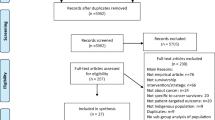

A total of 3766 records were retrieved from databases, with 2081 duplicates removed before screening. The remaining 1685 articles were screened by title and abstract based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, with 1494 articles not meeting inclusion criteria being excluded. After the full-text screening, authors agreed on the final ninety-one articles which have been included in this systematic review. The PRISMA flowchart of this process is below (Fig. 1) [19].

Characteristics of included studies

Of the 91 studies included in this review, 56% (n = 51) were quantitative studies, 34% (n = 31) were qualitative, 8% (n = 7) were quantitative descriptive, and 2% (n = 2) were mixed methods studies (See Fig. 2). Most of the qualitative studies aimed to explore the perceptions, beliefs, and cancer care experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living with cancer and possible barriers to accessing care [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], understanding the perspectives of health care providers and caregivers who provide care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples [39,40,41,42,43], and to describe the role of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health care workers in providing culturally appropriate health care services [44,45,46]. Of the quantitative studies, 5% (n = 5) assessed outcomes in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children specifically [47,48,49,50,51]. It was common among the included quantitative studies to assess survival outcomes and disparities. Over half (n = 4) of the quantitative descriptive design studies included assessed healthcare utilization [52,53,54,55].

Quality appraisal

Using the MMAT tool to assess the methodological quality of the included papers, almost all quantitative, quantitative descriptive, and qualitative papers (n = 87) met all the criteria. Two mixed methods studies did not adequately address all methodological quality criteria due to divergences and variations in the reporting of their methods. The detailed mixed-method appraisal of the included studies can be found in additional material (See Additional file 2).

Thematic analysis

The key themes identified in the thematic analysis were: Culture, family, and community; cancer outcomes; psychological distress; access to health care; cancer education and awareness; and lack of appropriate data. Table 2 provides quotes for each theme.

Theme one: culture, family, and community

The thematic analysis identified several concerns influencing the experiences of cancer for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples relating to cultural insensitivity, including lack of culturally appropriate care services, language barriers, poor understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ perspectives about cancer and the importance of family and community involvement [22, 27, 32, 40, 46, 61,62,63,64]. The majority of the included studies reported that care providers lacked an understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and how this shaped treatment decisions [42, 46, 65]. Included studies highlighted value differences between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and Western cultures [26, 27, 56]. Prioritizing family commitments and living in a community, were frequently stated as more important than health concerns for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples [26, 27, 56].

Theme two: cancer outcomes

The second theme identified cancer outcomes. Subthemes included advanced stage at diagnosis, presence of co-morbidities, longer time between diagnosis, and treatment commencement. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer were more likely to present with distant metastasis or stage IV cancer which contributed to a lower survival rate [66,67,68,69,70,71,72]. Included studies mentioned that the delayed presentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer was attributed to several causes, including lack of outreach services, communication barriers, complex health care system, limited health literacy, and fear and mistrust associated with cancer and its treatment [22, 56, 66, 71]. When analysing the burden of co-morbidities on cancer outcomes, a high proportion of included studies found that higher levels of co-morbidity were interweaved with poor treatment compliance and survival disadvantage; noting that poor treatment compliance does not imply a strengths-based approach, but is rather the dominant terminology used in the reviewed articles [68, 73,74,75,76]. Studies have found that the effect of co-morbidity varies with type and stage of cancer and more research is needed to explain the survival disparities of particular cancer types [57].

Theme three: psychological distress

Multiple stressors including financial worries, anxiety, fear, shame, and family role, in conjunction with a mistrust of non-traditional treatments, play important roles in shaping the perceptions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer. Included studies identified that worry about out-of-pocket costs related to accommodation and transport to and from hospitals were major unmet supportive care needs among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer [29, 35, 43, 77,78,79]. Emotional strain and anxiety related to accessibility and affordability of culturally appropriate care services, pre-existing health issues, invasive treatment and follow-up, and end-of-life care were associated with late diagnosis and poor prognosis [23, 36, 80,81,82]. Publications highlighted the need for psychological and emotional support to reduce cancer disparities among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, such as survival, mortality and incidence [26, 37, 45, 81, 83]. Included studies described how psychosocial factors like fear and shame can impact the length of treatment, as well as the type of treatment that is accessed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer, therefore impacting their survival [21, 24, 25, 27, 31, 46].

Theme four: access to healthcare

Distance to travel to cancer services, worry about transport to access healthcare services, and the necessity for more flexible care services were identified in two-thirds of the included studies. Other concerns raised were difficulty in access, coordination and continuation of cancer care, and a lack of Aboriginal health care workers [46, 61, 64]. Studies found that survival disparities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer increased proportionately with socio-economic disadvantage and geographic remoteness [48, 51, 84,85,86,87].

Researchers identified flexible supportive care services such as after-hour services, drop-in clinics, and telehealth services as enablers to improved accessibility and continuity of cancer treatment [20, 35, 43, 56]. Included studies mentioned the need for clear navigation of scheduling, booking, and follow-up information about appropriate treatment and allied health services [37, 41, 76, 81, 86]. Developing a trusting relationship with physicians and health care workers, and provisions to support seeing the same health practitioner during follow-up visits were identified as vital enablers to facilitate the continuity of care [30, 42, 47, 88, 89].

Theme five: cancer education and awareness

Cancer awareness, information and knowledge impacted the time taken to seek cancer treatment in included publications [21, 23, 33, 53, 54, 90, 91]. The median time taken to seek cancer treatment was found to be significantly higher in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer than non-Indigenous people with cancer [89]. Quotes presented in Table 2 demonstrate how different cultural beliefs and concepts like cancer is ‘contagious’, it’s a ‘payback’, means ‘bad luck’, caused by ‘black magic’, make Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer reluctant to talk about their symptoms and to ignore the warning signs [21, 22, 24, 27, 31, 52].

Theme six: lack of appropriate data

Included studies mentioned poor recording of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status when accessing cancer treatment, therefore limiting the availability of accurate data [55, 76, 92,93,94,95]. One study found that 23% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer had medical records that lacked information about the stage of lung cancer at diagnosis indicating a gap in the information collected [92]. The concern of the inadequate health-related quality of life (HRQoL) data for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer has also been identified, which is considered a benchmark tool to analyse present cancer care and the patient experience [96].

Discussion

This review aimed to investigate and synthesize the findings and recommendations about the experiences, outcomes, and supportive care needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer. The studies included in this review identified many disparities between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous people with cancer including later diagnoses, delays in treatment, and higher rates of co-morbidity [57, 70, 88]. The need for culturally safe healthcare sites and services was highlighted in the included studies, as was the need for better-designed targeted interventions and provisions for routine data collection [41].

There is a lack of appropriate data collected about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer. The recording of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status in health data repositories is commonly inadequate, with linked data sets still routinely misclassifying a significant proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples [97]. The current research is limited by inadequate and missing routinely collected data in national administrative and health datasets, and research datasets such as surveys reporting on health-related quality of life outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples [97]. National best practice standards exist to guide the routine collection of Indigenous status in health data sets, and other organisation level research has identified strategies to increase Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identification when collecting data [98, 99]. Providing opportunities for people to indicate their Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status should be a priority of all healthcare organisations, healthcare professionals and researchers [97]. Having accurate records of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia accessing healthcare, can help to ensure greater understanding of the healthcare issues and needs faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and can ensure the provision of culturally appropriate health services tailored to these needs.

Strong spiritual and cultural beliefs can also act as a barrier to optimal cancer care as there are longstanding attitudes that cancer is taboo and something to be ashamed of [24, 31]. The impact that these cultural beliefs have on the way that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples may perceive their diagnosis can also reduce the effectiveness of educational campaigns about significant risk factors such as tobacco and alcohol use [100]. These strong cultural beliefs may prevent people from participating in routine cancer screening out of avoidance, shame, and a lack of education about the benefits [33, 82, 101]. These attitudes, in turn, may prevent those diagnosed with cancer from accessing the recommended care and treatment [31, 82].

Similar to previous studies, the findings of this review found that a key enabler to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation in treatment services is provision of care that respects Aboriginal understanding of cancer and acknowledges the priority of family, community, and staying connected to country [27, 62, 64, 102]. Creating culturally aware spaces for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people undergoing cancer treatment was noted by many of the reviewed studies as being important to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples accessing timely and appropriate care [20]. Several studies also highlighted the role of Aboriginal liaison officers to ensure cultural appropriateness, treatment continuity, and co-ordination [42, 56, 65]. Likewise, included studies investigated improving communication between the health care professionals and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people affected by cancer, to strengthen treatment participation and adherence [32, 46, 53]. Education about cancer was identified as an important factor in supporting the provision of optimal care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in studies included in this review [31, 44, 56]. Educational tools which employ culturally specific information and contain the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples prove to be more effective than more generalized advice in supporting healthy behaviour changes [31, 61]. Researchers suggested that it is imperative to incorporate culturally relevant information and approaches into the design of cancer awareness programs, specific cancer information sheets and brochures for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, to both facilitate an accurate understanding of cancer information and to support cultural values [21, 33, 53, 102]. The provision of health education to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities is another critical component in increasing the understanding of cancer by improving health literacy, which can help to dispel the stigma and shame that arises from a misunderstanding of cancer. As such, healthcare services, and other community organisations must be equipped and supported to provide information, education and culturally appropriate spaces for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who have received a cancer diagnosis.

In the reciprocal, education for healthcare practitioners on the cultural values and beliefs held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was also found to be vital to ensuring culturally safe and appropriate cancer care. Previous reviews have found that cultural competency training for healthcare professionals can improve the health behaviours of their culturally diverse patients [103]. Cultural competency training, while not the only solution needed, is an important step in helping non-Indigenous healthcare professionals understand the intricacies of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ culture and how it can either help or hinder cancer care provision [30, 104]. It should be acknowledged that the cultural competency of healthcare professionals is reliant on societal level actors or “owners of the system” as they determine funding and the importance that is placed on delivering the best possible care. The onus is on governments, teaching facilities like universities and on upper management of healthcare services to ensure that healthcare professionals are confident and able to provide culturally safe care [105, 106].

This review has found culture as both a barrier and enabler for optimal cancer care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and highlights a need for more culturally safe services and targeted education for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Policy must reflect this need, with an increased focus on access for this priority population. The provision of culturally safe services should be accessible for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, regardless of their geographic location. To ensure that culturally appropriate care can be accessed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across Australia, there is a need to increase the availability of health services in rural and remote areas of Australia.

The findings of this review, while specific for the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ experiences in cancer care, could be extrapolated to other Indigenous groups in countries with similar publicly funded healthcare systems. Systematic reviews of cancer care elements in Canada’s Indigenous populations have been published, finding that the cultural safety of services, meaning the ability of services to recognise and respect the cultural needs and identities of consumers, is imperative to uptake and utilization [107,108,109].

Limitations

The MMAT tool, although tested for its veracity, is limited in scope when compared to other appraisal tools. The MMAT tool does not consider how the research was conducted with participants, therefore an additional tool which applies a cultural lens to the appraisal of research conducted about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was considered for this project.

Another limitation of this study is that the searches were conducted in January 2022, and due to delays in its synthesis, there may be more recent articles published after this search date. The research archive is continually evolving and so this systematic review provides an evidence base for which future reviews may expand upon.

Further, this review explicitly looked at studies of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with a previous diagnosis of cancer, meaning that other vital aspects of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cancer research, for example cancer screening and preventative behaviours, were beyond the scope of this review and warrant further investigation. The large number of included studies shows that the research investment is producing a sound research archive on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer. This investment, by both government and non-government organisations, must continue its momentum.

Conclusions

This review described the multifaceted, far-reaching impacts that cancer has on the experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and demonstrated that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples face many barriers to receiving optimal cancer care including difficulty in accessing culturally appropriate health services. Culture is both a barrier and facilitator to cancer care. By improving the cultural safety of health services, and by developing new programs and services to address the specific needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, it is expected that the disparity in cancer outcomes between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous people can be significantly reduced.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its additional information files].

Abbreviations

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- MMAT:

-

Mixed method appraisal tool

- ACCHO:

-

Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Organization

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia 2021. Canberra: AIHW; 2021.

Segelov E, Garvey G. Cancer and Indigenous populations: Time to end the disparity. JCO Global Oncology. 2020;6:80–2.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cultural safety in health care for Indigenous Australians: Monitoring framework. Canberra: AIHW; 2022.

Lowitja Institute. Transforming power: Voices for generational change. Melbourne: The Close the Gap Campaign Steering Committee; 2022.

Pearson O, Schwartzkopff K, Dawson A, Hagger C, Karagi A, Davy C, et al. Aboriginal community controlled health organisations address health equity through action on the social determinants of health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–13.

DiGiacomo M, Davidson PM, Abbott P, Delaney P, Dharmendra T, McGrath SJ, et al. Childhood disability in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: a literature review. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(1):7.

Panaretto KS, Wenitong M, Button S, Ring IT. Aboriginal community controlled health services: leading the way in primary care. Med J Aust. 2014;200(11):649–52.

Waterworth P, Pescud M, Braham R, Dimmock J, Rosenberg M. Factors Influencing the Health Behaviour of Indigenous Australians: Perspectives from Support People. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0142323.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: Smoking Trends, Australia. Canberra: Australian Government; 2017.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander specific primary health care: Results from the nKPI and OSR collections. Canberra: AIHW; 2022.

Australian Institute of Health Welfare. National Cervical Screening Program monitoring report 2023. Canberra: AIHW; 2023.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Bowel Cancer Screening Program: Monitoring report 2019. Canberra: AIHW; 2019.

Butler TL, Anderson K, Condon JR, Garvey G, Brotherton JML, Cunningham J, et al. Indigenous Australian women’s experiences of participation in cervical screening. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(6):e0234536.

Whop LJ, Butler TL, Lee N, Cunningham J, Garvey G, Anderson K, et al. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s views of cervical screening by self-collection: a qualitative study. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2022;46(2):161–9.

Ireland K, Hendrie D, Ledwith T, Singh A. Strategies to address barriers and improve bowel cancer screening participation in Indigenous populations, particularly in rural and remote communities: a scoping review. Health Promot J Austr. 2022;34(2):544–60.

Bonnefin A, Balafas A, Simone L, Bedford K, Voukelatos A, Hyde‐Page A, et al. Pivot to prevent bowel cancer: Reflections on adapting an Aboriginal bowel cancer screening awareness program to a digital call to action—A commentary. Health Promot J Austr. 2023.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285–91.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, The PRISMA, et al. statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020;2021:n71.

Dembinsky M. Exploring Yamatji perceptions and use of palliative care: An ethnographic study. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2014;20(8):387–93.

Gonzalez T, Harris R, Williams R, Wadwell R, Barlow-Stewart K, Fleming J, et al. Exploring the barriers preventing Indigenous Australians from accessing cancer genetic counseling. J Genet Couns. 2020;29(4):542–52.

Lyford M, Haigh MM, Baxi S, Cheetham S, Shaouli S, Thompson SC. An exploration of underrepresentation of Aboriginal cancer patients attending a regional radiotherapy service in Western Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(2):337.

Marcusson-Rababi B, Anderson K, Whop LJ, Butler T, Whitson N, Garvey G. Does gynaecological cancer care meet the needs of Indigenous Australian women? Qualitative interviews with patients and care providers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):606.

McGrath P, Holewa H, Ogilvie K, Rayner R, Patton MA. Insights on Aboriginal peoples’ views of cancer in Australia. Contemp Nurse. 2006;22(2):240–54.

McGrath P, Rawson N. Key factors impacting on diagnosis and treatment for vulvar cancer for Indigenous women: findings from Australia. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(10):2769–75.

Newman CE, Gray R, Brener L, Jackson LC, Dillon A, Saunders V, et al. “I had a little bit of a bloke meltdown… But the next day, I was up”: Understanding cancer experiences among Aboriginal men. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40(3):E1–8.

Prior D. The meaning of cancer for Australian Aboriginal women; changing the focus of cancer nursing. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13(4):280–6.

Ristevski E, Thompson S, Kingaby S, Nightingale C, Iddawela M. Understanding Aboriginal peoples’ cultural and family connections can help inform the development of culturally appropriate cancer survivorship models of care. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:124–32.

Shahid S, Finn L, Bessarab D, Thompson S. “Nowhere to room … nobody told them”: Logistical and cultural impediments to Aboriginal peoples’ participation in cancer treatment. Aust Health Rev. 2011;35(2):235–41.

Shahid S, Durey A, Bessarab D, Aoun SM, Thompson SC. Identifying barriers and improving communication between cancer service providers and Aboriginal patients and their families: the perspective of service providers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):460.

Shahid S, Finn L, Bessarab D, Thompson SC, Shahid S, Finn L, et al. Understanding, beliefs and perspectives of Aboriginal people in Western Australia about cancer and its impact on access to cancer services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:132.

Shahid S, Finn LD, Thompson SC, Shahid S, Finn LD, Thompson SC. Barriers to participation of Aboriginal people in cancer care: Communication in the hospital setting. Med J Aust. 2009;190(10):574–9.

Shahid S, Teng THK, Bessarab D, Aoun S, Baxi S, Thompson SC. Factors contributing to delayed diagnosis of cancer among Aboriginal people in Australia: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):11.

Tam L, Garvey G, Meiklejohn J, Martin J, Adams J, Walpole E, et al. Exploring positive survivorship experiences of Indigenous Australian cancer patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(1):135.

Taylor EV, Lyford M, Holloway M, Parsons L, Mason T, Sabesan S, et al. “The support has been brilliant”: experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients attending two high performing cancer services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–15.

Thompson S, Lyford M, Papertalk L, Holloway M. Passing on wisdom: Exploring the end-of-life wishes of Aborginal people from the Midwest of western Australia. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19(4):9.

Thompson SC, Shahid S, Bessarab D, Durey A, Davidson PM. Not just bricks and mortar: planning hospital cancer services for Aboriginal people. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:62.

Willis E, Dwyer J, Owada K, Couzner L, King D, Wainer J. Indigenous women’s expectations of clinical care during treatment for a gynaecological cancer: rural and remote differences in expectations. Aust Health Rev. 2011;35(1):99–103.

Bell L, Anderson K, Girgis A, Aoun S, Cunningham J, Wakefield CE, et al. “We have to be strong ourselves”: exploring the support needs of informal carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(14):7281.

Cuesta-Briand B, Bessarab D, Shaouli S, Thompson SC. Addressing unresolved tensions to build effective partnerships: Lessons from an Aboriginal cancer support network. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14:122.

de Witt A, Cunningham FC, Bailie R, Percival N, Adams J, Valery PC. “It’s just presence,” the contributions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health professionals in cancer care in Queensland. Front Public Health. 2018;6:344.

de Witt A, Matthews V, Bailie R, Garvey G, Valery PC, Adams J, et al. Communication, collaboration and care coordination: The three-point guide to cancer care provision for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Int J Integr Care. 2020;20(2):1–16.

Meiklejohn JA, Adams J, Valery PC, Walpole ET, Martin JH, Williams HM, et al. Health professional’s perspectives of the barriers and enablers to cancer care for Indigenous Australians. Eur J Cancer Care. 2016;25(2):254–61.

Finn LD, Pepper A, Gregory P, Thompson SC. Improving Indigenous access to cancer screening and treatment services: descriptive findings and a preliminary report on the Midwest Indigenous Women's Cancer Support Group. Australas Med J. 2008;1(2):1–21.

Ivers R, Jackson B, Levett T, Wallace K, Winch S. Home to health care to hospital: evaluation of a cancer care team based in Australian Aboriginal primary care. Aust J Rural Health. 2019;27(1):88–92.

Olver I, Gunn KM, Chong A, Knott V, Spronk K, Nayia C, et al. Communicating cancer and its treatment to Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients with cancer: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(1):431–8.

Jessop S, Ruhayel S, Sutton R, Youlden DR, Pearson G, Lu C, et al. Are outcomes for childhood leukaemia in Australia influenced by geographical remoteness and Indigenous race? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(4):8.

Rotte L, Hansford J, Kirby M, Osborn M, Suppiah R, Ritchie P, et al. Cancer in Australian Aboriginal children: Room for improvement. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49(1):27–32.

Valery PC, Youlden DR, Baade PD, Ward LJ, Green AC, Aitken JF. Cancer incidence and mortality in Indigenous Australian children, 1997–2008. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(1):156–8.

Valery PC, Youlden DR, Baade PD, Ward LJ, Green AC, Aitken JF. Cancer survival in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian children: What is the difference? Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(12):2099–106.

Youlden DR, Baade PD, McBride CA, Pole JD, Moore AS, Valery PC, et al. Changes in cancer incidence and survival among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in Australia, 1997–2016. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2022;69(4):e29492.

Bernardes CM, Beesley V, Shaouli S, Medlin L, Garvey G, Valery PC. End-of-life care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer: an exploratory study of service utilisation and unmet supportive care needs. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(4):2073–82.

Bernardes CM, Whop LJ, Garvey G, Valery PC. Health service utilization by Indigenous cancer patients in Queensland: A descriptive study. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(1):57–65.

Parikh DR, Diaz A, Bernardes C, De Ieso PB, Thachil T, Kar G, et al. The utilization of allied and community health services by cancer patients living in regional and remote geographical areas in Australia. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(6):3209–17.

Valery PC, Bernardes CM, de Witt A, Martin J, Walpole E, Garvey G, et al. Patterns of primary health care service use of Indigenous Australians diagnosed with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(1):317–27.

Anderson K, Diaz A, Parikh DR, Garvey G. Accessibility of cancer treatment services for Indigenous Australians in the Northern Territory: Perspectives of patients and care providers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–13.

Diaz A, Baade PD, Valery PC, Whop LJ, Moore SP, Cunningham J, et al. Comorbidity and cervical cancer survival of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian women: a semi-national registry-based cohort study (2003–2012). PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0196764.

Woods JA, Johnson CE, Ngo HT, Katzenellenbogen JM, Murray K, Thompson SC. Delay in commencement of palliative care service episodes provided to Indigenous and non-Indigenous patients: Cross-sectional analysis of an Australian multi-jurisdictional dataset. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:11.

Page BJ, Bowman RV, Yang IA, Fong KM. A survey of lung cancer in rural and remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Queensland: health views that impact on early diagnosis and treatment. Intern Med J. 2016;46(2):171–6.

Condon JR, Armstrong BK, Barnes T, Zhao YJ. Cancer incidence and survival for Indigenous Australians in the northern territory. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2005;29(2):123–8.

Basnayake TL, Valery PC, Carson P, De Ieso PB. Treatment and outcomes for Indigenous and non-Indigenous lung cancer patients in the Top End of the Northern Territory. Intern Med J. 2021;51(7):1081–91.

Gibberd A, Supramaniam R, Dillon A, Armstrong BK, O’Connell DL. Lung cancer treatment and mortality for Aboriginal people in New South Wales, Australia: Results from a population-based record linkage study and medical record audit. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:1–11.

Weir K, Supramaniam R, Gibberd A, Dillon A, Armstrong BK, O’Connell DL. Comparing colorectal cancer treatment and survival for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in New South Wales. Med J Aust. 2016;204(4):1561.e1-e8.

Hall SE, Bulsara CE, Bulsara MK, Leahy TG, Culbong MR, Hendrie D, et al. Treatment patterns for cancer in Western Australia: does being Indigenous make a difference? Med J Aust. 2004;181(4):191–4.

Le H, Penniment M, Carruthers S, Roos D, Sullivan T, Baxi S. Radiation treatment compliance in the Indigenous population: The pilot Northern Territory experience and future directions. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2013;57(2):218–21.

Gibberd A, Supramaniam R, Dillon A, Armstrong BK, O’Connell DL. Are Aboriginal people more likely to be diagnosed with more advanced cancer? Med J Aust. 2015;202(4):195–200.

Luke C, Tracey E, Stapleton A, Roder D. Exploring contrary trends in bladder cancer incidence, mortality and survival: Implications for research and cancer control. Intern Med J. 2010;40(5):357–62.

Moore SP, Green AC, Garvey G, Coory MD, Valery PC. A study of head and neck cancer treatment and survival among Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Queensland, Australia, 1998 to 2004. BMC Cancer. 2011;11(1):460.

Shaw IM, Elston TJ. Retrospective, 5-year surgical audit comparing breast cancer in Indigenous and non-Indigenous women in Far North Queensland. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73(9):758–60.

Supramaniam R, Gibberd A, Dillon A, Goldsbury DE, O’Connell DL. Increasing rates of surgical treatment and preventing comorbidities may increase breast cancer survival for Aboriginal women. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):163.

Tervonen HE, Walton R, You H, Baker D, Roder D, Currow D, et al. After accounting for competing causes of death and more advanced stage, do Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with cancer still have worse survival? A population-based cohort study in New South Wales. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:398.

Tomita Y, Karapetis CS, Roder D, Beeke C, Hocking C, Roy AC, et al. Comparable survival outcome of metastatic colorectal cancer in Indigenous and non-Indigenous patients: retrospective analysis of the South Australian metastatic colorectal cancer registry. Aust J Rural Health. 2016;24(2):85–91.

Banham D, Roder D, Eckert M, Howard NJ, Canuto K, Brown A, et al. Cancer treatment and the risk of cancer death among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal South Australians: Analysis of a matched cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):771.

Martin JH, Coory MD, Valery PC, Green AC. Association of diabetes with survival among cohorts of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians with cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(3):355–60.

Slape DR, Saunderson RB, Tatian AH, Forstner DF, Estall VJ. Cutaneous malignancies in Indigenous Peoples of urban Sydney. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2019;63(2):244–9.

Whop LJ, Baade PD, Brotherton JML, Canfell K, Cunningham J, Gertig D, et al. Time to clinical investigation for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Queensland women after a high grade abnormal pap smear, 2000–2009. Med J Aust. 2017;206(2):73–7.

Bernardes CM, Diaz A, Valery PC, Sabesan S, Baxi S, Aoun S, et al. Unmet supportive care needs among Indigenous cancer patients across Australia. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19(3):1–11.

Diaz A, Bernardes CM, Garvey G, Valery PC. Supportive care needs among Indigenous cancer patients in Queensland, Australia: Less comorbidity is associated with greater practical and cultural unmet need. Eur J Cancer Care. 2016;25(2):242–53.

Valery PC, Bernardes CM, Beesley V, Hawkes AL, Baade P, Garvey G. Unmet supportive care needs of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders with cancer: a prospective, longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(3):869–77.

Bernardes CM, Langbecker D, Beesley V, Garvey G, Valery PC. Does social support reduce distress and worry among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer? Cancer Rep. 2019;2(4):e1178.

McMichael C, Kirk M, Manderson L, Hoban E, Potts H. Indigenous women’s perceptions of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in Queensland. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000;24(5):515–9.

Meiklejohn JA, Arley BD, Pratt G, Valery PC, Bernardes CM. “We just don’t talk about it”: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ perceptions of cancer in regional Queensland. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19(2):1–9.

Meiklejohn JA, Bailie R, Adams J, Garvey G, Bernardes CM, Williamson D, et al. “I’m a Survivor”: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cancer survivors’ perspectives of cancer survivorship. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43(2):105.

Elder-Robinson E, Diaz A, Howard K, Parikh DR, Kar G, Garvey G. Quality of life in the first year of cancer diagnosis among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people living in regional and remote areas of Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1):10.

Frydrych AM, Slack-Smith LM, Parsons R, Threlfall T. Oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: Characteristics and survival in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Western Australians. Open Dent J. 2014;8:168–74.

Laurvick CL, Semmens JB, Holman DJ, Leung YC. Ovarian cancer in Western Australia (1982–98): Incidence, mortality and survival. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2003;27(6):588–95.

Parker C, Tong SYC, Dempsey K, Condon J, Sharma SK, Chen JWC, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Australia’s Northern Territory: High incidence and poor outcome. Med J Aust. 2014;201(8):470–4.

Ho-Huynh AHN, Elston TJ, Gunnarsson RK, De Costa A. Achieving high breast cancer survival for women in rural and remote areas. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2022;23(1):101–7.

Tan JY, Otty ZA, Vangaveti VN, Buttner P, Varma SC, Joshi AJ, et al. A prospective comparison of times to presentation and treatment of regional and remote head and neck patients in North Queensland, Australia. Int Med J. 2016;46(8):917–24.

Condon JR, Barnes T, Armstrong BK, Selva-Nayagam S, Elwood JM. Stage at diagnosis and cancer survival for Indigenous Australians in the Northern Territory. Med J Aust. 2005;182(6):277–80.

Fitzadam S, Lin EM, Creighton N, Currow DC. Lung, breast and bowel cancer treatment for Aboriginal people in New South Wales: a population-based cohort study. Intern Med J. 2021;51(6):879–90.

Coory MD, Green AC, Stirling J, Valery PC. Survival of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Queenslanders after a diagnosis of lung cancer: A matched cohort study. Med J Aust. 2008;188(10):562–6.

Diaz A, Moore SP, Martin JH, Green AC, Garvey G, Valery PC. Factors associated with cancer-specific and overall survival among Indigenous and non-Indigenous gynecologic cancer patients in Queensland, Australia: a matched cohort study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25(3):542–7.

Supramaniam R, Grindley H, Pulver LJ. Cancer mortality in Aboriginal people in New South Wales, Australia, 1994–2002. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2006;30(5):453–6.

Valery PC, Coory M, Stirling J, Green AC. Cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survival in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians: a matched cohort study. Lancet. 2006;367(9525):1842–8.

Garvey G, Cunningham J, He VY, Janda M, Baade P, Sabesan S, et al. Health-related quality of life among Indigenous Australians diagnosed with cancer. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(8):1999–2008.

Nelson MA, Lim K, Boyd J, Cordery D, Went A, Meharg D, et al. Accuracy of reporting of Aboriginality on administrative health data collections using linked data in NSW, Australia. BMC Med Res Method. 2020;20(1):267.

Health AIo, Welfare. National best practice guidelines for collecting Indigenous status in health data sets. Canberra: AIHW; 2010.

NSW Aboriginal Affairs. Aboriginal identification in NSW: The way forward. Sydney: NSW Government; 2015.

Davidson P, Jiwa M, DiGiacomo M, Sarah M, Newton P, Durey A, Bessarab D, et al. The experience of lung cancer in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and what it means for policy, service planning and delivery. Aust Health Rev. 2013;37(1):1–8.

Javanparast S, Ward PR, Carter SM, Wilson CJ. Barriers to and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening in different population subgroups in Adelaide, South Australia. Med J Aust. 2012;196(8):521–3.

Baade PD, Dasgupta P, Dickman PW, Cramb S, Williamson JD, Condon JR, et al. Quantifying the changes in survival inequality for Indigenous people diagnosed with cancer in Queensland, Australia. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;43:1–8.

Horvat L, Horey D, Romios P, Kis-Rigo J. Cultural competence education for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;5:CD009405.

Sanjida S, Garvey G, Ward J, Bainbridge R, Shakeshaft A, Hadikusumo S, et al. Indigenous Australians’ experiences of cancer care: a narrative literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(24):16947.

Herrera CA, Rada G, Kuhn-Barrientos L, Barrios X. Does ownership matter? An overview of systematic reviews of the performance of private for-profit, private not-for-profit and public healthcare providers. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12):e93456.

Clifford A, Janya Mc C, Jongen C, Bainbridge R. Cultural Competency Training and Education in the University-based Professional Training of Health Professionals: Characteristics, Quality and Outcomes of Evaluations. Divers Equal Health Care. 2017;14(3):136–47.

Gifford W, Rowan M, Dick P, Modanloo S, Benoit M, Al Awar Z, et al. Interventions to improve cancer survivorship among Indigenous Peoples and communities: a systematic review with a narrative synthesis. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(11):7029–48.

Horrill TC, Linton J, Lavoie JG, Martin D, Wiens A, Schultz ASH. Access to cancer care among Indigenous peoples in Canada: a scoping review. Soc Sci Med. 2019;238:112495.

Williams R. Cultural safety — what does it mean for our work practice? Aust N Z J Public Health. 1999;23(2):213–4.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Professor Peter Baade in the conceptualization of this review. Special thanks to Kanchana Ekanayake, Academic Liaison Librarian at The University of Sydney Library, for her assistance in designing and conducting the literature searches.

Funding

This review was funded by Cancer Council Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, JG, MH and MV.; Methodology, JG, MH and BB.; Software, FN, DM; Validation, JG, MH, FN, DM and JM; Formal Analysis, JG, MH, FN, DM, JM; Data Curation, FN, DM, JM; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, DM, JG, MH, and FN.; Writing – Review & Editing, DM, JM, AM, KW, MV, TB and BB.; Supervision, JG, MV, TB; Project Administration, FN, DM; Funding Acquisition, MV.

Authors' information

JG is a Yuin man from the NSW South Coast. MH is an Aboriginal woman who has always lived on Dharug country.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Bibliographic table of included studies.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Critical appraisal of included studies using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).

Additional file 3: Table S3.

PRISMA 2020 guidelines for systematic reviews checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gilroy, J., Henningham, M., Meehan, D. et al. Systematic review of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ experiences and supportive care needs associated with cancer. BMC Public Health 24, 523 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18070-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18070-3