Abstract

Background

Creating a healthy, decent and safe workplace and designing quality jobs are ways to eliminate precarious work in organisations and industries. This review aimed at mapping evidence on how psychosocial safety climate (PSC) influence health, safety and performance of workers.

Methods

A literature search was conducted in four main databases (PubMed, Scopus, Central and Web of Science) and other online sources like Google Scholar. A reference list of eligible studies was also checked for additional papers. Only full-text peer-reviewed papers published in English were eligible for this review.

Results

A search in the databases produced 13,711 records, and through a rigorous screening process, 93 papers were included in this review. PSC is found to directly affect job demands, job insecurity, effort-reward imbalance, work-family conflict, job resources, job control and quality leadership. Moreover, PSC directly affects social relations at work, including workplace abuse, violence, discrimination and harassment. Again, PSC has a direct effect on health, safety and performance outcomes because it moderates the impact of excessive job demands on workers’ health and safety. Finally, PSC boosts job resources’ effect on improving workers’ well-being, safety and performance.

Conclusion

Managers’ efforts directed towards designing quality jobs, prioritising the well-being of workers, and fostering a bottom-up communication through robust organisational policies, practices, and procedures may help create a high organisational PSC that, in turn, promotes a healthy and decent work environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Every job has tremendous inherent health, safety and well-being challenges, thus, creating a safe and decent work for improved health and safety outcomes becomes eminent [1, 2]. For instance, pprecarious jobs and work environment are detrimental to the health and safety of workers and place huge financial burden on workers and their organisations [2]. Occupational incidents do not affect only workers and their families, but have a huge burden on society through impaired productivity and increased use of healthcare and cost [3, 4]. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) working conditions are worsening globally, and majority of workers are found in precarious employment [1], which is responsible for about 7,600 deaths daily [1]. Therefore, occupational health and safety (OHS) remains the key factor to restoring dignity at work and improving worker health outcomes, to meet the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target 8, which seeks to eliminate all forms of precarious work and ensure a decent and safe workplace for all [1]. However, robust research designs and reviews are needed to map quality evidence to inform interventions and policies aimed at creating such a safe and decent work for all workers.

Evidence from the World Health Organisation (WHO) and ILO shows that in 2016, about 1.9 million deaths occurred globally due to occupational accidents and injuries [5]. Again in 2017, about 2.78 million workers died from occupational-related accidents and injuries [6, 7]. Thus, globally, about 7,600 workers died daily in 2017 due to precarious and unhealthy working conditions, but this affects poor developing nations disproportionately. For instance, the African region recorded the highest global occupational communicable diseases among over one-third of its working population and 20% of its workforce has experienced serious work-related accidents [1]. These unfortunate trends of statistics are frightening and might be as a result of insufficient safety regulations and enforcement as well as emerging industries and technological advancements which may require updated safety protocols and training [1]. Also, these figures give the indication that most workers, especially those in developing countries do not have access to a decent, safe and healthy workplace [5, 8]. Perhaps, global economic pressures are forcing some industries and organisations to focus on cost-cutting and increase productivity instead of protecting the well-being and safety of their workers [1]. There is the need for adequate measures and pragmatic steps taken by national regional and global bodies to guarantee decent, safe, and healthy workplace for all workers [5, 8]

Evidence shows that global occupational morbidity and mortality from psychosocial hazards keep increasing, something that need urgent attention [5, 8]. Psychosocial working conditions or exposure to psychosocial hazards by workers, to a greater extent, is dependent on the interplay between job demands and job resources (job design) [9, 10]. Most work stress models such as the job demand-resource, job demand-control and effort-reward imbalance argue that work environments with high job demands and fewer job resources expose workers to impaired health outcomes that lead to impaired performance and less productivity [11]. Psychosocial safety climate (PSC) has been the basis for job designs and improving social relations at work, perhaps it is capable of prioritising the well-being and safety of workers [12]. Besides, PSC is capable of buffering the effect of high job demands on workers’ health and safety [11].

In organisations with high PSC, the well-being and safety of workers are prioritised [11, 12], commitments and efforts are made by senior management to involve and leverage workers’ participation in designing jobs and programmes that help create a safe and healthy work environment for improved well-being, safety and productivity [12]. Empirical evidence from work stress, organisational psychology and safety science showed PSC as a unifying framework for dealing with work stress [11]. While there is a growing body of research work exploring PSC, not enough is understood about its importance and application to psychosocial working conditions, health and safety, and performance of workers. Hence, this review maps evidence on the influence of PSC on psychosocial working conditions, health and safety, and performance, thus, to inform workplace policies and actions that create a safe, decent and healthy workplace for all workers to achieve SDG 8 and improve organisational performance.

Methods

The authors carried out this scoping review using the guidelines by Arksey and O’Malley [13], by identifying and stating the research questions, identifying relevant studies, study selection, data collection, data summary and synthesis of results, and consultation. Two research questions guided this review. (1) What is the influence of PSC on (a) psychosocial work factors, (b) health and safety outcomes of workers, and (c) performance and productivity outcomes? (2) what is the moderating role of PSC in the health erosion and motivation pathways?

Authors created a search technique that employed a combination of controlled vocabularies like Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords for each of the four major electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, Central and Web of Science) to address the research questions and map relevant literature. Table 1 illustrates the search strategy conducted in PubMed. The search strategy used in PubMed was then modified for search in other databases. The authors used four key words in their search strategy (1) psychosocial safety climate, (2) psychosocial work factors, (3) Health and safety and (4) performance.

Additional searches were conducted in Google, Google Scholar, JSTOR, Emerald, and Taylor and Francis to gather adequate and relevant peer-reviewed papers for this review. Reference lists of eligible full-text articles were also searched for additional papers. A chartered librarian was consulted during the search for literature and data screening process. The authors started the search for papers on December 5, 2022, and ended on March 29, 2023. The authors developed eligibility criteria for data screening. Studies published in the year 2010 and later were included because we were interested in studies that explored PSC using PSC-12 and that PSC-12 was published in 2010 [12] (See Table 2 for details on eligibility criteria).

The Mendeley software was used to remove duplicates. Abstracts and full-text records were screened and papers selected based on eligibility criteria. Data from eligible papers were extracted independently by MA and reviewed by EWA and JOS. Disagreements among authors during the data screening and extraction phases were resolved during weekly meetings to ensure accuracy in extracted data. Data extracted included authors, purpose of the study, design, population, sample size, measure for PSC, and study outcomes. These data were relevant to help map evidence to answer the research questions and make relevant recommendations for future studies. Extracted data is presented in Table S1. The authors read through the final extracted data, organised data into themes and results presented and discussed.

Results

Search results

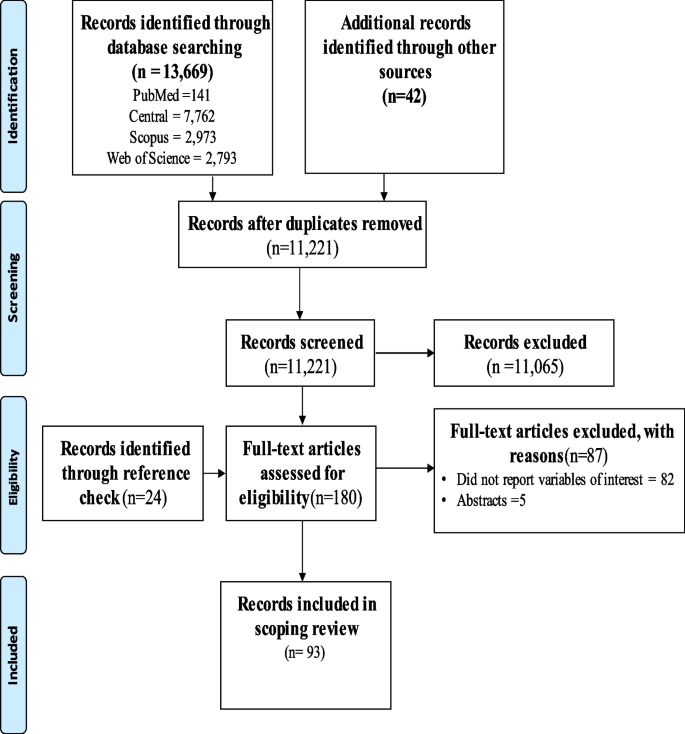

The results from the four main databases yielded 13,669 records and additional search produced 42 records. After removing duplicates (2,490 records) using the Mendeley software, 11,221 records were available for screening. After removing non-full text and records irrelevant to the review, 156 full-text records were available for further screening. Checking of reference lists of full-text records produced additional 24 records. Thus, 180 records were finally screened. Finally, 87 full-text records were excluded, the remaining 93 were included in the thematic synthesis (See Fig. 1 for search results and screening process).

Study characteristics

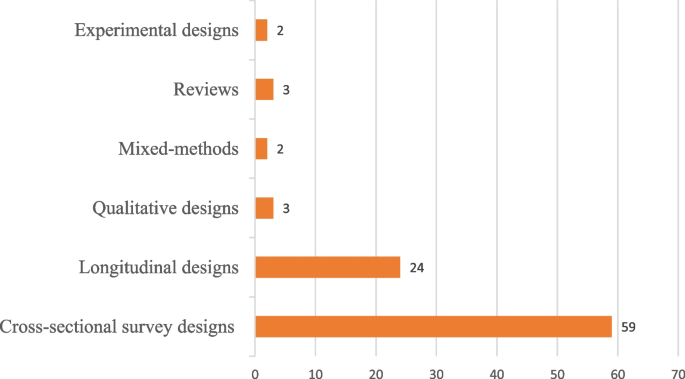

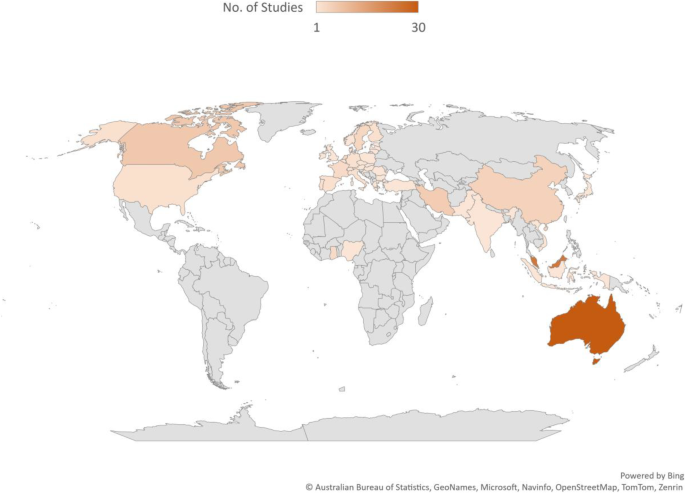

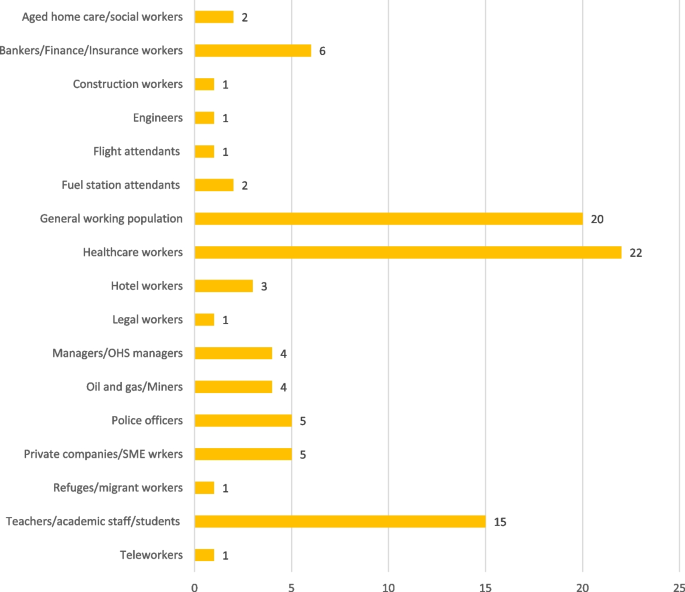

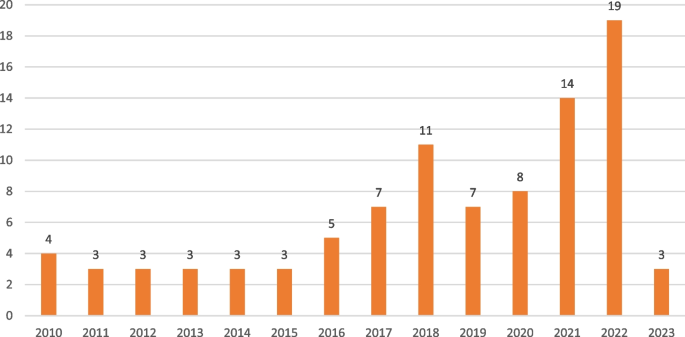

Most reviewed studies used a cross-sectional survey design (See details in Fig. 2), and were conducted among workers in Australia (30) and Malaysia (24) [See details in Fig. 3]. The general working population, healthcare workers and workers in academia remained the most explored groups using PSC (See Fig. 4 for more details). Most of the reviewed studies were published in the year 2022 (See Fig. 5 for more details).

Findings

Findings from this review were reported based on the two research questions, and into four sections; (1) influence PSC on psychosocial work factors, (2) influence of PSC on health and safety, (3) influence of PSC on performance outcomes and (4) the moderating effect of PSC.

Influence of PSC on psychosocial work factors

Three sub-themes were developed from the findings of the reviewed studies. The themes are job demands, job resources, and hostile work factors.

Job demands

Evidence is strongly established in the literature that PSC is negatively and significantly associated with job demands [12, 14,15,16,17,18,19]. PSC has a significant and negative association with cognitive demands [20], psychological demands [15, 21,22,23], emotional demands [22, 24,25,26], quantitative demands [27], work intensification [28], work pressure [25, 29], conflicting pressure [30], workload [25], long-working hours [31], hindrance demands [32,33,34,35,36], challenge demands [32] and compulsive working [37]. However, a reviewed study found no significant association between PSC and challenge hindrance [36]. Job insecurity [38], work-family conflict [14, 38,39,40], effort-reward imbalance [41] and family-work conflict [39] are reduced in high PSC context.

Job resources

Job resources are high in a positive PSC context at various occupational settings [17,18,19, 21, 42,43,44,45]. Key job resources such as job control [26, 46, 47], decision authority [21], decision influence [48], skill discretion [21, 25], co-worker support [38], supervisor support [22, 46], managerial support [49], organisational support [50] and organisational rewards [22, 51] were found to have a positive and significant association with PSC. Furthermore, workers in a high PSC work environment were more likely to perceive a high possibility for development [20], organisational justice [22, 52], health-centric [53], quality leadership [27, 54], psychological capital [55] and emotional resources [45] at work.

Workplace abuse

PSC had a negative and significant association with workplace bullying [29, 51, 56,57,58,59,60,61], and that, workplace violence [29, 62], physical or verbal abuse [63], and harassment [29, 51] were reduced or eliminated in the presence of a high-level PSC.

Influence of PSC on worker health and safety

Findings indicated that burnout [19, 27, 33,34,35, 59, 64], job strain [65, 66] and emotional exhaustion [21, 22, 24, 25, 48, 61, 67] might be a result of low organisational PSC. Also, fatigue [68, 69], injuries [67], accidents [70] and circulatory diseases [71] had a significant and negative association with PSC. Moreover, mental health issues such as psychological distress [23, 26, 42, 49, 54, 64, 67], stress [27, 72], depression [31, 41, 65, 73] and PTSD [56] might be a result of low workplace PSC. Meanwhile, reviewed studies found that workers that perceived high levels of PSC at work were more likely to experience improved general health, safety and well-being [12, 16, 17, 55, 57, 62, 74], psychological well-being [15, 58], personal resilience [75], psychological safety [54, 76], and self-worth [77].

Influence of PSC on job performance outcomes

Improved job performance was linked to higher perceived organisational PSC [32]. Similarly, job satisfaction [17, 27, 77, 78], work engagement [17, 21, 22, 25, 27, 37, 42, 57, 69, 79, 80] and job commitment [27, 44, 52] are three key performance outcomes (psychosocial outcomes) that were consistently reported to be associated with high level of PSC. However, two studies reported no significant association between PSC and job engagement [44, 81], but improved productivity was expected in a highly perceived PSC work environment [20, 75]. As a result, issues that affected productivity, such as turnover intentions [41, 61, 78], absenteeism [71, 82, 83], presenteeism [23, 28, 82, 84], and need thwarting [40] were reduced or eliminated in highly perceived PSC work environment. These might lead to more funding opportunities [47], sustained profits [83] and reduced compensation claims [83].

Elimination of unsafe working behaviours [85] and improvement in workplace safety behaviours [38, 86], safety participation [87] and compliance [87] were also common in workplaces where management prioritises the well-being of workers. Workers were more likely to be workaholics [44], have high morale [83], and develop organisational citizenship behaviours [50] in a high PSC context. Moreover, adaptive and proactive work behaviours [88], creative problem solving [55, 89], taking of personal initiatives [80], personal development [80], positive service behaviour [88], workaround [68], and service recovery performance [90] were more likely to be observed in high PSC work environment. Perhaps, managerial quality is one of the key benefits in a high organisational PSC context [64, 91]. For instance, the quality of patient care and patient safety was protected when healthcare professionals perceived high PSC in their facilities [30, 70].

The moderating role of PSC

One key strength of PSC was its buffering effect on precarious work conditions on health, safety and performance outcomes [11].

The effect of workplace abuse on workers’ health and safety

The effect of workplace abuse and violence on workers’ health and safety is controlled by the presence of PSC. For instance, reviewed studies reported that PSC moderated the effect of workplace bullying on psychological contract violation [92], work engagement [57, 79], PTSD [56]and psychological distress [52]. Also, PSC played a moderating role in the effect of workplace harassment on psychological distress [52], and the impact of workplace stigma on bullying and burnout [59]. Contrary to the argument of Dollard et al. [11], the moderating role of PSC on the association between workplace bullying and psychological contract violation had an inverse result [92].

The effect of job demands on workers’ health and safety

Evidence also indicated that PSC could buffer the effect of job demands on workers’ health and safety. For example, the effect of job demands on burnout [81], fatigue [69], work engagement [69] and depression [93] were found to be moderated by PSC. Also, the association between emotional demands and emotional exhaustion [12] and psychological distress [94] were reduced in the presence of high-level organisational PSC. Furthermore, the relationship between work-family conflict and insecurity, as well as the association between job insecurity and safety behaviours are buffered by the presence of workplace PSC [38]. The high level of workplace PSC among nurses reduced the effect of work intensity on presenteeism [29].

The effect of job resources on workers’ health and safety

It was expected that in a high PSC work environment, job resources’ effect on workers’ health and safety would be enhanced [11]. For instance, the effect of job resources on safety behaviours [38], and workaholism [43] were boosted in the presence of high PSC. Evidence also showed that the effect of social support (support from co-workers and supervisors) on work engagement [81]and the effect of job control on mindfulness among workers improved in the presence of high PSC [95]. Moreover, a reviewed study found that a supportive work environment’s effects on personal hope were lowered in low PSC [76]. Besides, health-centred leadership had the greatest impact on psychological health when oil and gas workers perceived high PSC [53]. Finally, the interaction between job demands and job resources in predicting distress among police workers was moderated by PSC [26].

The effect of mental health on workers’ behaviours

In an unsafe work environment, workers’ mental health is severely impaired [88]. In such a situation, the high presence of PSC is expected to control the effect of mentally distressed on workers’ performance [12]. A reviewed study confirmed this hypothesis and reported that the effect of depression on workers’ positive organisational behaviour was attenuated by the presence of PSC [17].

Discussion

A thorough literature search conducted in PubMed, Scopus, Central and Web of Science and other databases such as Google and Google scholar produced 13,669 records. Through a robust screening process, 91 studies that explored psychosocial safety climate using PSC-12, PSC-8 and PSC-4 as a measure were included in this review. Reviewed studies showed that PSC, as an upstream job resource construct, was essential in designing jobs by matching job demands and resources. Thus, PSC has consistently been found in the literature to be negatively associated with job demand variables such as psychological demands, emotional demands, quantitative demands, work intensification, work pressure, conflicting pressures, job insecurity, work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and effort-reward imbalance. Moreover, PSC is positively associated with job resources (job control, social support, quality leadership, organisational rewards, decision authority and influence, emotional resources, organisational justice, and personal development). Hence, PSC has great influence on psychosocial work factors (job demands and job resources). Also, it was established that PSC was negatively associated with workplace abuse, such as stigma, discrimination, bullying, and harassment. Furthermore, PSC directly improves workers’ health, safety, and performance, proving a strong buffering effect for health and safety of workers. This shows that PSC has influence of health and safety and performance outcome of workers and reduce the effect of precarious work on the health and safety of workers. Discussion of findings have been done according to the research questions.

PSC as a precursor to psychosocial work factors (job demands and resources)

Managers need to be guided by ethics and value for workers when making decisions regarding job design and nature to foster healthy and decent workplaces [96]. However, job design and the promotion of a healthy and decent workplace might depend on the priority managers give to productivity or profits as against the well-being and safety of the workers [11]. In many cases where the manager’s priority was overly focused on productivity and profits, job demands were high, affecting workers’ health and safety, especially in a resource-limited work environment [12]. However, when managers shift attention from productivity to well-being and safety of their workers, excessive job demands are likely to be reduced, to protect the health of the workers. Perhaps, the negative association between job demands and PSC is explained by the shift of managers’ attention from productivity to valuing the psychological well-being and safety of the workers and vice versa.

The review further found that in a low PSC context, excessive job demands are expected, due to the lack of feedback from workers or the lack of opportunity for workers to voice their frustrations concerning high level of job demands [59]. In such organisations, job demands were likely to be high because of the likelihood that managers prioritised an up-to-bottom communication rather than a bottom-up approach, to ensure that workers’ voices are heard and factored into the job designs [43, 95]. There is high likelihood of reduced job demands when organisational PSC is high, because workers will be involved, consulted, participated in designing their jobs, workplace health and safety policies and any intervention that creates a healthy and decent workplace for such workforce. Finally, PSC was observed as an upstream job resource and its presence at the workplace is a signal for reduction in excessive job demands and helping workers to fulfil their requirements, that achieve organisational goals and a sense of belongingness [11].

The quality of a worker’s productivity or performance is influenced by the design of their job, which also establishes how workers would carry out their responsibilities and meet organisational and personal goals. It is worth appreciating that quality work involved resourcing workers adequately to cope with excessive job demands [12, 44]. The positive association between job resources and PSC indicates that in a high PSC work environment, workers have the confidence to access the needed resources to accomplish their job demands and responsibilities [43]. Thus, in such a context, workers are encouraged, trained and offered the opportunities not only to access job resources but to utilise these resources for organisational and personal growth [11]. Besides, in a high PSC context, adequate job resources are made available to workers to ensure that the psychological well-being of workers are prioritised over productivity. On the other hand, in a low PSC context, job resources were limited and, to a larger extent, non-existing, which exposes workers to job strain and poor health outcomes [12], that will further compromise productivity.

Workplace abuse and violence are unhealthy factors that exposed workers to precarious situations. We found that workplace abuse, bullying, harassment, stigma and discrimination were social-relational factors that created an unhealthy, corrupt and indecent workplace, violated human rights, and compromised the dignity of workers [56, 61]. Various mechanisms might explain the negative association between PSC and workplace abuse. First, in a high PSC context, workplace social relations are supposed to improve and give workers the signal that there are available resources for dealing with any form of abuse [12]. Also, workers who are abused victims were given opportunities to find solutions in such positive worksites [12, 71]. This way of solving workplace conflicts or abuse might not be present in a low PSC work context which may fuel turnover intentions and turnovers of affected workers [41, 78]. Finally, it would be difficult for many workers to report abuse in organisations where PSC is low, and that majority of these workers may not have the opportunity to seek redress since such institutions practice the top–bottom approach communication that usually limits open communication and trust in management [41]. But, in a high PSC context, managers give cues to workers about social-relational aspects of work, such as how workers should interact with one another and the behaviours that would be rewarded or punished [12].

PSC as a precursor to workers’ health and safety

Evidence suggests that PSC positively correlated with improved worker health, safety and performance outcomes [13, 97]. High-quality work with manageable job demands, and adequate job resources were more likely in a high PSC work environment, where managers value and safeguard workers’ psychological health for improved well-being, safety and performance outcomes [18, 59, 66]. Thus, a high PSC context foster satisfaction of psychological needs, job satisfaction, job commitment, and mental health maintenance, which translate into improved productivity [58, 88, 89]. Basically, in such a PSC context, workers perceive that their well-being is a priority to managers, hence, become intrinsically motivated, which may lead to improved mental health and well-being [98, 99], and positive performance outcomes. Unfortunately, low PSC environments are more likely to produce low-quality work that threatens and obstructs worker job satisfaction, resulting in psychological distress, exhaustion, fatigue, impaired well-being and organisational performance [62, 68].

The moderating role of PSC

The evidence is that PSC moderates the effect of psychosocial work factors on health, safety, and performance outcomes [26]. One explanation is that PSC acts as a safety signal [52], when danger cues such as work pressure, excessive job demands, and workplace abuse are present. This safety signal works by indicating options such as access to and safe use of available resources to counteract the psychosocial hazards to prevent the onset of impaired health, safety and performance outcomes [26, 54]. Aside from being a safety signal, PSC could initiate resource caravans or gain spirals, promoting workers’ well-being and productivity [96]. A study found that PSC moderated the association between workplace bullying and psychological contract violation [93]. It is worth noting that receiving support at the workplace was not always be connected with favourable health and performance outcomes, primarily when the support is obtained in an unsafe or negative work environment [93], making the organisational climate increasingly important.

Implications for practice

Creating and promoting a healthy, safe and decent workplace might start with integrating PSC as an essential upstream psychosocial resource at every workplace. Moreover, efforts directed towards prioritising and valuing the well-being and safety of workers by managers may be the beginning of eliminating precarious working condition. Thus, the experience of workers at the workplace, to a greater extent, influence workers perception of PSC. Still, this premise does not change the fact that managers possess the power and resources to design quality jobs through pro-worker and robust organisational policies and practices [12]. Dollard et al. [12] argued that PSC was a modifiable variable; hence, managers should know that change could be implemented by improving involvement and communication mechanisms around psychosocial hazards and mental health issues. This could also be achieved by management demonstrating commitment and support for stress prevention and psychological treatment. Furthermore, managers commitment becomes paramount to any workplace policies targeting workers’ well-being [24, 92].

Workers who experienced bullying were more prone to rage and irritation, which have undesired consequences to the worker and the organisation. Thus, managers need to pay attention to these signals and act quickly to relieve workers of distressing feelings. Managers need to give workers channels to vent their rage since doing so would make them feel better [100]. Organisations could, for instance, offer victims psychological counselling services and listen to their complaints. Understanding the implicit expectations from fair treatment of workers may also help managers to manage and deliver on the expectations of employees, which in turn, helps prevent violations and other adverse outcomes. Perhaps, fostering a bottom-up approach to communication allows workers to report excessive job demands and low job resources and enables workers to talk about workplace abuse and hostility [35, 100,101,102,103,104,105]. Also, managers need to create a safe and decent psychosocial work environment that may lower the risk of workplace bullying and can successfully prevent the events leading to an escalation of vices and eventually increase productivity and organisational image [106,107,108,109,110].

Recommendations for future research

Reviewed studies exploring PSC were mainly conducted in Australia, Malaysia and Canada, and not much research attention was given in Africa and South America. Also, existing PSC literature concentrates on occupational groups such healthcare workers, education workers, police and workers in the banking sector. Hence, studies from developing nations and other worker groups such as agricultural workers, road transport workers, rescue workers and military officers are needed. Moreover, the direct effect of PSC on some psychosocial work factors such as lone working, shift workers and those working extended hours may need more exploration. Furthermore, more studies are required to tease out the conditions under which the strength of PSC matters in the work context [12]. In addition, qualitative designs are needed to understand PSC through shared and individual experiences, working conditions and the psychological health of workers. More quality studies that adjust for confounding variables may be essential in understanding the independent effect of PSC on psychosocial work factors and stress symptoms. Finally, understanding PSC through the experiences of minority workers such as refugees, child workers, pregnant workers, and workers in the informal sectors might help improve the working conditions of vulnerable workers.

Limitations in this review

About 63% of the included studies are cross-sectional surveys whose findings might be affected by response bias since they mostly rely on self-report measures. This situation may affect the generalisation of findings in this review. Also, the literature search was restricted to only peer-reviewed articles and papers published in English. This situation may affect the number of included studies and the depth of information presented in this review. Including only papers that explored PSC using PSC-12, PSC-8 and PSC-4 as measures may reduce the number of included studies which also affect the depth of information provided in this review. However, the authors pulled 93 studies from 45 countries globally, which may help understand PSC’s importance in creating a safe and healthy work environment for workers.

Conclusion

Organisational PSC is an essential upstream job resource that directly affects psychosocial work factors, including job demands, job insecurity, effort-reward imbalance, work-family conflict, job resources, job control and quality leadership. In addition, PSC directly affects social relations at work, including workplace abuse, violence, discrimination and harassment. Moreover, PSC directly affects health, safety, and performance outcomes. Besides, PSC moderates the effect of working conditions on workers’ health, safety and performance across different occupational groups and settings. Therefore, designing quality jobs, prioritising the well-being of workers and fostering bottom-up communication through robust organisation policies, practices, and procedures may help create a high workplce PSC for healthy and decent work for all workers, for productivity and organisational integrity.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files (Table S1).

References

ILO. Safety and health at the heart of future of work: building on 100 years of experience. Geneva; 2019. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@safework/documents/publication/wcms_678357.pdf. Accessed 11 Jul 2023.

Rantanen J, Muchiri F, Lehtinen S. Decent work, ILO’s response to the globalization of working life: Basic concepts and global implementation with special reference to occupational health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3351. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103351.

Reese CD. Occupational safety and health: fundamental principles and philosophies. New York: CRC Press; 2017. https://doi.org/10.1201/B21975/OCCUPATIONAL-SAFETY-HEALTH-CHARLES-REESE. Accessed 21 Jan 2023.

Reese CD. Occupational health and safety management: a practical approach. New York: CRC Press; 2018. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781351228848.

WHO, ILO. WHO/ILO joint estimates of the work-related burden of disease and injury, 2000–2016: global monitoring report. Geneva; 2021. https://ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_819705/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed 11 Jul 2023.

Hämäläinen P, Takala J, Kiat TB. Global estimates of occupational accidents and work-related illnesses 2017. World. 2017;3–4.

Takala J, Hämäläinen P, Nenonen N, Takahashi K, Chimed-ochir O, Rantanen J. Comparative analysis of the burden of injury and illness at work in selected countries and regions. Cent Eur J Occup Environ Med. 2017;23:6–31.

WHO, ILO. WHO/ILO: Almost 2 million people die from work-related causes each year. WHO/ILO: Almost 2 Million People Die from Work-Related Causes Each Year 2021. https://www.who.int/news/item/16-09-2021-who-ilo-almost-2-million-people-die-from-work-related-causes-each-year (accessed November 16, 2021).

Driscoll T, Rushton L, Hutchings SJ, Straif K, Steenland K, Abate D, et al. Global and regional burden of disease and injury in 2016 arising from occupational exposures: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77:133–41. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2019-106008.

Sorensen G, Dennerlein JT, Peters SE, Sabbath EL, Kelly EL, Wagner GR. The future of research on work, safety, health and wellbeing: a guiding conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med. 2021;269:113593.

Peters SE, Grogan H, Henderson GM, Gómez MAL, Maldonado MM, Sanhueza IS, et al. Working conditions influencing drivers’ safety and well-being in the transportation industry: “on board” program. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(19):10173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910173.

Dollard M, Dormann C, Idris M. Psychosocial safety climate: a new work stress theory and implications for method. Springer International Publishing; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20319-1.

Ansah EW, Mintah JK, Ogah JK. Psychosocial safety climate predicts health and safety status of Ghanaian fuel attendants. Univers J Public Health. 2018;6:63–72.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract. 2005;8:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Parkin AK, Zadow AJ, Potter RE, Afsharian A, Dollard MF, Pignata S, et al. The role of psychosocial safety climate on flexible work from home digital job demands and work-life conflict. Ind Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2022-0078.

Idris MA, Dollard MF, Coward J, Dormann C. Psychosocial safety climate: Conceptual distinctiveness and effect on job demands and worker psychological health. Saf Sci. 2012;50:19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2011.06.005.

Ansah EW, Kwarteng J, Mensah O. Mediating effect of psychosocial safety climate and job resources in the job demands-health relation: implications for contemporary business management. Am Int Coll J Bus Manag. 2020;3:74–83.

Hall GB, Dollard MF, Coward J. Psychosocial safety climate: development of the PSC-12. Int J Stress Manag. 2010;17:353–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021320.

Idris MA, Dollard MF. Psychosocial safety climate, work conditions, and emotions in the workplace: a malaysian population-based work stress study. Int J Stress Manag. 2011;18:324–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024849.

Idris MA, Dollard MF, Winefield AH. Integrating psychosocial safety climate in the JD-R model: a study amongst Malaysian workers. SA J Ind Psychol. 2011;37:1–11. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v37i2.851.

Krasniqi V, Hoxha A. The effect of psychosocial safety climate on work engagement through possibilities for development and cognitive demands. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2022;55:88–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2022.12.016.

Afsharian A, Zadow A, Dollard MF. Psychosocial factors at work in the Asia Pacific. Psychosocial Factors at Work in the Asia Pacific: From Theory to Practice, Springer International Publishing Switzerland; 2016, p. 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44400-0_10.

Afsharian A, Dollard M, Ziaian T. Psychosocial safety climate psychosocial safety climate. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20319-1.

Biron C, Karanika-Murray M, Ivers H, Salvoni S, Fernet C. Teleworking while sick: a three-wave study of psychosocial safety climate, psychological demands, and presenteeism. Front Psychol. 2021;12:1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.734245.

Idris MA, Dollard MF, Yulita. Psychosocial safety climate, emotional demands, burnout, and depression: A longitudinal multilevel study in the Malaysian private sector. J Occup Health Psychol 2014;19:291–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036599.

Dollard MF, Bakker AB. Psychosocial safety climate as a precursor to conducive work environments, psychological health problems, and employee engagement. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2010;83:579–99. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X470690.

Dollard MF, Tuckey MR, Dormann C. Psychosocial safety climate moderates the job demand-resource interaction in predicting workgroup distress. Accid Anal Prev. 2012;45:694–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2011.09.042.

Berthelsen H, Muhonen T, Bergström G, Westerlund H, Dollard MF. Benchmarks for evidence-based risk assessment with the swedish version of the 4-item psychosocial safety climate scale. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228675.

Mansour S, Faisal Azeem M, Dollard M, Potter R. How psychosocial safety climate helped alleviate work intensification effects on presenteeism during the COVID-19 crisis? a moderated mediation model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(20):13673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013673.

Bailey TS, Dollard MF, McLinton SS, Richards PAM. Psychosocial safety climate, psychosocial and physical factors in the aetiology of musculoskeletal disorder symptoms and workplace injury compensation claims. Work Stress. 2015;29:190–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2015.1031855.

McLinton SS, Dollard MF, Tuckey MMR. New perspectives on psychosocial safety climate in healthcare: A mixed methods approach. Saf Sci. 2018;109:236–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2018.06.005.

Zadow AJ, Dollard MF, Dormann C, Landsbergis P. Predicting new major depression symptoms from long working hours, psychosocial safety climate and work engagement: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6):e044133.

Teoh KB, Gan KH, Kee DMH. Psychosocial safety climate and job performance among penang island hoteliers: The mediating roles of challenge demands and hindrance demands. Asia Pac Soc Sci Rev. 2021;21:100–11.

Teoh KB, Gan KH, Seow XT. The psychosocial safety climate and burnout among Penang hoteliers. Proceedings of the Phuket International Conference; 2021. p. 96–108.

Teoh KB, Kee DMH, Akhtar N. How does psychosocial safety climate affect burnout among malaysian educators during the covid-19 pandemic? Asia Pac Soc Sci Rev. 2021;21:86–99.

Teoh KB, Kee DMH. Psychosocial safety climate and burnout among academicians: the mediating role of work engagement. Int J Soc Syst Sci. 2020;12(1):1–4.

Yulita, Idris MA, Dollard MF. A multi-level study of psychosocial safety climate, challenge and hindrance demands, employee exhaustion, engagement and physical health. psychosocial factors at work in the Asia Pacific 2014:127–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8975-2_6.

Platania S, Morando M, Caruso A, Scuderi VE. The effect of psychosocial safety climate on engagement and psychological distress: a multilevel study on the healthcare sector. Safety. 2022;8(3):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety8030062.

Bronkhorst B. Behaving safely under pressure: The effects of job demands, resources, and safety climate on employee physical and psychosocial safety behavior. J Safety Res. 2015;55:63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSR.2015.09.002.

Mansour S, Tremblay DG. How can we decrease burnout and safety workaround behaviors in health care organizations? the role of psychosocial safety climate. Pers Rev. 2019;48:528–50. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-07-2017-0224.

Huyghebaert T, Gillet N, Fernet C, Lahiani FJ, Fouquereau E. Leveraging psychosocial safety climate to prevent ill-being: the mediating role of psychological need thwarting. J Vocat Behav. 2018;107:111–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.03.010.

Owen MS, Bailey TS, Dollard MF. Psychosocial Safety Climate as a Multilevel Extension of ERI Theory: Evidence from Australia. In: Siegrist J, Wahrendorf M, editors. Work Stress and Health in a Globalized Economy. Aligning Perspectives on Health, Safety and Well-Being: Springer International Publishing Switzerland; 2016. p. 189–217.

Lee MCC, Idris MA. Psychosocial safety climate versus team climate: the distinctiveness between the two organizational climate constructs. Pers Rev. 2017;46:988–1003. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-01-2016-0003.

Yulita Y, Idris MA, Dollard MF. Effect of psychosocial safety climate on psychological distress via job resources, work engagement and workaholism: a multilevel longitudinal study. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2022;28:691–708. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2020.1822054.

Gan KH, Kee DMH. Psychosocial safety climate, work engagement and organizational commitment in Malaysian research universities: the mediating role of job resources. Foresight. 2022;24:694–707. https://doi.org/10.1108/FS-01-2021-0019.

Chin Chin Lee M, Lunn J. Testing the relevance, proximal, and distal effects of psychosocial safety climate and social support on job resources: a context-based approach. Cogent Psychol. 2019;6(1):1685929. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2019.1685929.

Dollard MF, Opie T, Lenthall S, Wakerman J, Knight S, Dunn S, et al. Psychosocial safety climate as an antecedent of work characteristics and psychological strain: a multilevel model. Work Stress. 2012;26:385–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2012.734154.

Xie L, Lin G, Hon C, Xia B, Skitmore M. Comparing the psychosocial safety climate between megaprojects and non-megaprojects: evidence from China. App Sci (Switzerland). 2020;10:1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10248809.

Dollard MF, Karasek RA. Building psychosocial safety climate: evaluation of a socially coordinated par risk management stress prevention study. Contemp Occup Health Psychol Glob Perspect Res Pract. 2010;1:208–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470661550.ch11.

Yulita, Dollard MF, Idris MA. Climate congruence: How espoused psychosocial safety climate and enacted managerial support affect emotional exhaustion and work engagement. Saf Sci 2017;96:132–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.03.023.

Tariq A, Bukahri SMI, Adil A. Perceived organizational support as the moderator between psychosocial safety climate and organizational citizenship behaviour among nurses. Found Univ J Psychol. 2021;5:86–93.

Law R, Dollard MF, Tuckey MR, Dormann C. Psychosocial safety climate as a lead indicator of workplace bullying and harassment, job resources, psychological health and employee engagement. Accid Anal Prev. 2011;43:1782–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2011.04.010.

Viseu J, Guerreiro S, de Jesus SN, Pinto P. Effect of psychosocial safety climate and organizational justice on affective commitment: a study in the Algarve hotel sector during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hum Resour Hosp Tour. 2022;22:320–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2023.2154035.

Mirza MZ, Memon MA, Dollard M. A time-lagged study on health-centric leadership styles and psychological health: the mediating role of psychosocial safety climate. Current Psychology 2021:2021–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02140-5.

Sjöblom K, Mäkiniemi JP, Mäkikangas A. “I Was Given Three Marks and Told to Buy a Porsche”—Supervisors’ experiences of leading psychosocial safety climate and team psychological safety in a remote academic setting. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):12016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912016.

Brunetto Y, Saheli N, Dick T, Nelson S. Psychosocial safety climate, psychological capital, healthcare SLBs’ wellbeing and innovative behaviour during the COVID 19 Pandemic. Public Perform Manag Rev. 2022;45:751–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2021.1918189.

Bond SA, Tuckey MR, Dollard MF. Psychosocial safety climate, workplace bullying, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress. Organ Dev J. 2010;28:37–56.

Nguyen DTN, Teo STT, Grover SL, Nguyen NP. Psychological safety climate and workplace bullying in Vietnam’s public sector. Public Manag Rev. 2017;19:1415–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1272712.

Dollard MF, Dormann C, Tuckey MR, Escartín J. Psychosocial safety climate (PSC) and enacted PSC for workplace bullying and psychological health problem reduction. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2017;26:844–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2017.1380626.

Klinefelter Z, Sinclair RR, Britt TW, Sawhney G, Black KJ, Munc A. Psychosocial safety climate and stigma: Reporting stress-related concerns at work. Stress Health. 2021;37:488–503. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3010.

Kwan SSM, Tuckey MR, Dollard MF. The role of the psychosocial safety climate in coping with workplace bullying: a grounded theory and sequential tree analysis. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2016;25:133–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2014.982102.

Escartín J, Dollard M, Zapf D, Kozlowski SWJ. Multilevel emotional exhaustion: psychosocial safety climate and workplace bullying as higher level contextual and individual explanatory factors. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2021;30:742–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2021.1939412.

Pien LC, Cheng Y, Cheng WJ. Psychosocial safety climate, workplace violence and self-rated health: a multi-level study among hospital nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2019;27:584–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12715.

Afsharian A, Dollard M, Miller E, Puvimanasinghe T, Esterman A, De Anstiss H, et al. Refugees at work: the preventative role of psychosocial safety climate against workplace harassment, discrimination and psychological distress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(20):10696. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010696.

Parent-Lamarche A, Biron C. When bosses are burned out: psychosocial safety climate and its effect on managerial quality. Int J Stress Manag. 2022;29:219–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000252.

Bailey TS, Dollard MF, Richards PAM. A national standard for psychosocial safety climate (PSC): PSC 41 as the benchmark for low risk of job strain and depressive symptoms. J Occup Health Psychol. 2015;20:15–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038166.

Gazica MW, Powers SR, Kessler SR. Imperfectly perfect: examining psychosocial safety climate’s influence on the physical and psychological impact of perfectionism in the practice of law. Behav Sci Law. 2021;39:741–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2546.

Zadow AJ, Dollard MF, Mclinton SS, Lawrence P, Tuckey MR. Psychosocial safety climate, emotional exhaustion, and work injuries in healthcare workplaces. Stress Health. 2017;33:558–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2740.

Mansour S, Tremblay DG. Psychosocial safety climate as resource passageways to alleviate work-family conflict: a study in the health sector in Quebec. Pers Rev. 2018;47:474–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2016-0281.

Garrick A, Mak AS, Cathcart S, Winwood PC, Bakker AB, Lushington K. Psychosocial safety climate moderating the effects of daily job demands and recovery on fatigue and work engagement. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2014;87:694–714. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12069.

McLinton SS, Afsharian A, Dollard MF, Tuckey MR. The dynamic interplay of physical and psychosocial safety climates in frontline healthcare. Stress Health. 2019;35:650–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2898.

Becher H, Dollard MF, Smith P, Li J. Predicting circulatory diseases from psychosocial safety climate: a prospective cohort study from Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:415. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH15030415.

Havermans BM, Boot CRL, Houtman ILD, Brouwers EPM, Anema JR, Van Der Beek AJ. The role of autonomy and social support in the relation between psychosocial safety climate and stress in health care workers. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4484-4.

Dormann C, Owen M, Dollard M, Guthier C. Translating cross-lagged effects into incidence rates and risk ratios: The case of psychosocial safety climate and depression. Work Stress. 2018;32:248–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1395926.

Dollard MF, Neser DY. Worker health is good for the economy: Union density and psychosocial safety climate as determinants of country differences inworker health and productivity in 31 European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2013;92:114–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.028.

Siami S, Gorji M, Martin A. Psychosocial safety climate and supportive leadership as vital enhancers of personal hope and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stress Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3192.

Rasdi I, Ismail NF, Shyen Kong AS, Saliluddin SM. Introduction to customized occupational safety and health website and its effectiveness in improving psychosocial safety climate (psc) among police officers. Malaysian J Med Health Sci. 2018;14:67–73.

Xie L, Luo Z, Xia B. Influence of psychosocial safety climate on construction workers’ intent to stay, taking job satisfaction as the intermediary. Eng Constr Archit Manag 2022. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-12-2021-1082.

Geisler M, Berthelsen H, Muhonen T. Retaining social workers: the role of quality of work and psychosocial safety climate for work engagement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Hum Serv Organ Manag Leadersh Gov. 2019;43:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2019.1569574.

Tagoe T, Amponsah-Tawiah K. Psychosocial hazards and work engagement in the Ghanaian banking sector: the moderating role of psychosocial safety climate. Int J Bank Mark. 2020;38:310–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-04-2019-0136.

Lee MC, Idris MA. Psychosocial safety climate within the model of proactive motivation. Psychosocial safety climate: a new work stress theory. 2019:149–68.

Bronkhorst B, Vermeeren B. Safety climate, worker health and organizational health performance Testing a physical, psychosocial and combined pathway. Int J Workplace Health Manag. 2016;9:270–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-12-2015-0081.

Winwood PC, Bowden R, Stevens F. Psychosocial safety climate: role and significance in aged care. Occup Med Health Aff. 2013;01(6):135–40. https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-6879.1000135.

Alshamsi AI, Santos A, Thomson L. Psychosocial safety climate moderates the effect of demands of hospital accreditation on healthcare professionals: a longitudinal study. Front Health Serv. 2022;2:1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/frhs.2022.824619.

Liu B, Lu Q, Zhao Y, Zhan J. Can the psychosocial safety climate reduce ill-health presenteeism? evidence from chinese healthcare staff under a dual information processing path lens. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082969.

Yu M, Li J. Psychosocial safety climate and unsafe behavior among miners in China: the mediating role of work stress and job burnout. Psychol Health Med. 2020;25:793–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2019.1662068.

Akanni AA, Ajila CO, Omisile IO, Ndubueze KN. Mediating effect of work self-efficacy on the relationship between psychosocial safety climate and workplace safety behaviors among bank employees after Covid-19 lockdown. Cent Eur J Manag. 2021;29:2–13. https://doi.org/10.7206/cemj.2658-0845.38.

Mirza MZ, Isha ASN, Memon MA, Azeem S, Zahid M. Psychosocial safety climate, safety compliance and safety participation: the mediating role of psychological distress. J Manag Organ. 2022;28:363–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2019.35.

Siami S, Gorji M, Martin A. Psychosocial safety climate and psychological capital for positive customer behavioral intentions in service organizations. Am J Bus. 2023;38(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/ajb-01-2022-0018.

Oppert ML, Dollard MF, Murugavel VR, Reiter-Palmon R, Reardon A, Cropley DH, et al. A mixed-methods study of creative problem solving and psychosocial safety climate: preparing engineers for the future of work. Front Psychol. 2022;12:1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.759226.

Mansour S, Nogues S, Tremblay DG. Psychosocial safety climate as a mediator between high-performance work practices and service recovery performance: an international study in the airline industry. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2022;33:4215–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1949373.

Biron C, Parent-Lamarche A, Ivers H, Baril-Gingras G. Do as you say: the effects of psychosocial safety climate on managerial quality in an organizational health intervention. Int J Workplace Health Manag. 2018;11:228–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-01-2018-0009.

Rai A, Agarwal UA. Indian perspectives on workplace bullying: a decade of insights. Indian perspectives on workplace bullying. Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd; 2018. p. 79–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1017-1_4.

Hall GB, Dollard MF, Winefield AH, Dormann C, Bakker AB. Psychosocial safety climate buffers effects of job demands on depression and positive organizational behaviors. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2013;26:355–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2012.700477.

Lawrie EJ, Tuckey MR, Dollard MF. Job design for mindful work: the boosting effect of psychosocial safety climate. J Occup Health Psychol. 2018;23:483–95. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000102.

Loh MY, Idris MA, Dollard MF, Isahak M. Psychosocial safety climate as a moderator of the moderators: Contextualizing JDR models and emotional demands effects. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2018;91:620–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12211.

Yaris C, Ditchburn G, Curtis GJ, Brook L. Combining physical and psychosocial safety: a comprehensive workplace safety model. Saf Sci. 2020;132:104949.

Bakker A. A job demands–resources approach to public service motivation. Public Adm Rev. 2015;75:723–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12388.

Schaufeli WB. Applying the Job Demands-Resources model: a ‘how to’ guide to measuring and tackling work engagement and burnout. Organ Dyn. 2017;46:120–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.04.008.

Saptura AD, Rahmatia A, Wahyuningsih SH, Surwanti A. Strengthening work engagement through digital engagement, gamification and psychosocial safety climate in digital transformation. J Innov Bus Econ. 2021;5:35–48.

Teoh KB, Kee DMH. Psychosocial safety climate and burnout among Malaysian research university academicians: the mediating roles of job demands and work engagement. Int J Trade Glob Mark. 2022;15:471–96. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijtgm.2022.125910.

Siami S, Martin A, Gorji M, Grimmer M. How discretionary behaviors promote customer engagement: the role of psychosocial safety climate and psychological capital. J Manag Organ. 2022;28:379–97. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2020.29.

Zinsser KM, Zinsser A. Two case studies of preschool psychosocial safety climates. Res Hum Dev. 2016;13:49–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2016.1141278.

Teoh KB. Psychosocial safety climate and burnout among Malaysian academicians: the mediating role of job demands. Academia Letters. 2021;4:92–9.

Seddighi H, Dollard MF, Salmani I. Psychosocial safety climate of employees during COVID-19 in iran: a policy analysis. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2020;16. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.370.

Vaktskjold Hamre K, Valvatne Einarsen S, Notelaers G. Psychosocial safety climate as a moderator in role stressor- bullying relationships: a multilevel approach. Saf Sci. 2023;164:106165.

Inoue A, Eguchi H, Kachi Y, Tsutsumi A. Perceived psychosocial safety climate, psychological distress, and work engagement in Japanese employees: a cross-sectional mediation analysis of job demands and job resources. J Occup Health. 2023;65:e12405.

Weaver B, Kirk-Brown A, Goodwin D, Oxley J. Psychosocial safety behavior: a scoping review of behavior-based approaches to workplace psychosocial safety. J Safety Res. 2023;84:33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSR.2022.10.006.

Potter RE, Dollard MF, Owen MS, O’Keeffe V, Bailey T, Leka S. Assessing a national work health and safety policy intervention using the psychosocial safety climate framework. Saf Sci. 2017;100:91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.05.011.

Yulita, Idris MA, Abdullah SS. Psychosocial safety climate improves psychological detachment and relaxation during off-job recovery time to reduce emotional exhaustion: A multilevel shortitudinal study. Scand J Psychol 2022;63:19–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12789.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Kwame Kodua-Ntim of Sam Jonah Library, University of Cape Coast, Ghana, for his enormous support during data search and screening process.

Funding

This work received no funding support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation, design, data collection and analysis, and initial write-up, M.A, E.W.A, and J.O.S. E.W.A examined and oversaw the review process. The final draft of the manuscript was read and authorised for publication by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Dataextracted from reviewed studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Amoadu, M., Ansah, E.W. & Sarfo, J.O. Influence of psychosocial safety climate on occupational health and safety: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 23, 1344 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16246-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16246-x