Abstract

Background

Problematic screen use, defined as an inability to control use despite private, social, and professional life consequences, is increasingly common among adolescents and can have significant mental and physical health consequences. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are important risk factors in the development of addictive behaviors and may play an important role in the development of problematic screen use.

Methods

Prospective data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study (Baseline and Year 2; 2018–2020; N = 9,673, participants who did not use screens were excluded) were analyzed in 2023. Generalized logistic mixed effects models were used to determine associations with ACEs and the presence of problematic use among adolescents who used screens based on cutoff scores. Secondary analyses used generalized linear mixed effects models to determine associations between ACEs and adolescent-reported problematic use scores of video games (Video Game Addiction Questionnaire), social media (Social Media Addiction Questionnaire), and mobile phones (Mobile Phone Involvement Questionnaire). Analyses were adjusted for potential confounders including age, sex, race/ethnicity, highest parent education, household income, adolescent anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit symptoms, study site, and participants who were twins.

Results

The 9,673 screen-using adolescents ages 11–12 years old (mean age 12.0) were racially and ethnically diverse (52.9% White, 17.4% Latino/Hispanic, 19.4% Black, 5.8% Asian, 3.7% Native American, 0.9% Other). Problematic screen use rates among adolescents were identified to be 7.0% (video game), 3.5% (social media), and 21.8% (mobile phone). ACEs were associated with higher problematic video game and mobile phone use in both unadjusted and adjusted models, though problematic social media use was associated with mobile screen use in the unadjusted model only. Adolescents exposed to 4 or more ACEs experienced 3.1 times higher odds of reported problematic video game use and 1.6 times higher odds of problematic mobile phone use compared to peers with no ACEs.

Conclusions

Given the significant associations between adolescent ACE exposure and rates of problematic video and mobile phone screen use among adolescents who use screens, public health programming for trauma-exposed youth should explore video game, social media, and mobile phone use among this population and implement interventions focused on supporting healthy digital habits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Problematic screen use has risen dramatically among adolescents; 45% of adolescents report being online “almost constantly.” [1] Screen use becomes problematic when the user experiences a loss of control over usage and impairments in personal, social, and occupational functioning [2]. More specifically, we define problematic screen use as demonstrating key elements of the six core components of behavioral addiction: salience (the activity dominates thinking), mood modification (the activity impacts mood), tolerance (increasing time spent on the activity is needed to achieve previous effects), withdrawal (mood worsens when the activity is discontinued or reduced), conflict (the activity negatively impacts relationships), and relapse (a pattern of returning to use following a period of abstinence or improved control) [3]. These problematic use patterns can span a variety of modalities, including video games, social media, and phones [2, 4,5,6]. Problematic video game use is characterized by a sense of euphoria while playing, inability to stop, craving more time, low mood when not playing, and consequences in private, social and professional life [2]. Problematic social media use is characterized by an internalized need to be constantly connected via technology [5, 7]. Problematic mobile phone use includes a broader range of applications (i.e. texting, apps, video chat) but shares the same behavioral characteristics as those described above [6]. Given that excessive screentime and screen addictions are associated with reductions in physical activity [8], increased risk of obesity [5, 9], and psychological consequences including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety, and depression [2, 5,6,7, 10], identifying risk factors to inform prevention and intervention efforts is critical.

Recent research has highlighted that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), defined as potentially traumatic events that occur before the age of 18, are an important risk factor in developing addictive behaviors [11, 12]. Several studies have shown that adolescents who have experienced childhood trauma have a higher risk of developing problematic video game [13, 14], internet [15,16,17], and mobile phone use [18]. However, few studies have explored this relationship in a large, nationally representative U.S. sample in the setting of recent screen use increases. Further, few studies have used youth self-report screen-time data or focused on early adolescents, an age range when a spike in computer use, gaming, and social media use often occurs [19]. Moreover, the relationship between ACEs and problematic social media use has yet to be explored. This study aims to fill these gaps by examining the associations between ACEs and problematic video game, social media, and mobile phone use among a large, nationally representative sample of U.S. early adolescents. It is hypothesized that higher adolescent ACE scores will be associated with higher rates of problematic video game, social media, and phone use among youth who report screen use.

Methods

This study used a prospective design to determine the association between ACE score and problematic screen use among U.S. early adolescents. This study used survey data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, a large, diverse, prospective cohort study of brain development and health among adolescents from 21 recruitment sites across the U.S [20]. To maximize retention, research staff connects with families at least every six months by telephone and every year in person. To prevent higher attrition rates from lower-income families, the study provides a free nutrition and exercise program, a meal, homework assistance, childcare for other family members who accompanied the participant to the visits, and transportation vouchers during research visits. Youth who did not participate in any type of screen use (video game, social media, or mobile phone, were excluded (n = 2,112) The final sample consisted of 9,763 adolescents ages 11–12 years old during the two-year follow-up (4.0 release). Centralized institutional review board (IRB) approval was received from the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). Written informed consent and assent were obtained from caregivers and the child, respectively.

Measures

Exposure variables

ACE score was calculated through adolescent and parent responses from the baseline (2016–2018) survey. The ABCD study assesses nine of ten ACEs reflecting the items in the original CDC-Kaiser ACE study across different surveys as a validated ACEs screener was not administered. This generated scale has been used in prior ABCD literature and is based Hoffman et al.’ recommendations [21,22,23,24]. Supplemental Table 1 highlights how these questions map onto validated ACEs questions. Emotional abuse was not assessed in the ABCD study and therefore not included. ACE score was then categorized as 0 through ≥ 4, as a cumulative ACE score of ≥ 4 has documented greater risk concentration at this threshold [25, 26].

Outcome variables

Adolescents completed the following questionnaires at the two-year follow-up (4.0 release), the first time these surveys were administered.

The Video Game Addiction Questionnaire (VGAQ) is a six-question instrument used to assess problematic video game use. The questions were adapted from the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale [27]. The Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale consists of a single factor structure questionnaire assessing the six core components of behavioral addiction (salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, relapse) and has been validated in numerous different clinical and cultural contexts [28,29,30], but authors have previously extrapolated its application to broader video game addiction among early adolescents and college students [4, 31]. Questions assessing components of addiction include “I spend a lot of time thinking about playing video games” and “I’ve become stressed or upset if I am not allowed to play video games.” Likert-type scale responses ranged from 1 (never) to 6 (very often). Participants who reported any video game use on weekdays or weekends were asked these items. Responses were averaged from 0 to 6. If a response was missing, the average was calculated based on available responses. Participants who reported no use were excluded. Of note, 99.5% of participants completed the entire subscale once started. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85, mean 2.1, SD 1.1, and range 1–6. A cutoff score of 4 or greater was characterized as problematic video game use based on conservative suggestions from the Bergen Facebook Addition Scale literature [27, 32].

The Social Media Addiction Questionnaire (SMAQ) is a six-question survey also adapted from the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale that assesses the six aforementioned components of behavioral addiction [33]. The SMAQ has been extrapolated to problematic social media use among early adolescent, high school, and college students [4, 31, 34, 35]. Example questions include “I feel the need to use social media apps more and more” and “I use social media apps so much that it has had a bad effect on my schoolwork or job.” Likert-type scale responses ranged from 1 (never) to 6 (very often). Participants who reported having at least one social media account were asked these items. Participants who reported no use were excluded. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.82, mean 1.8, SD 0.9, and range 1–6. As above, a cutoff score of 4 or greater was classified as problematic social media use [32, 33].

The eight question Mobile Phone Involvement Questionnaire (MPIQ) is an 8-item survey developed to assess problematic phone use in adolescents and also measures the core components of behavioral addiction including salience, euphoria, withdrawal, and tolerance [36]. This instrument has been previously used in a study of U.S. high school students examining smartphone dependence [37]. Examples include “I lose track of how much I am using my phone” and “Arguments have arisen because of my phone use.” Likert-type scale responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Participants who reported having mobile phones were asked these items. Responses were averaged from 0 to 7. Participants who reported no use were excluded. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79, mean 3.1 SD 1.1, and range 1–7. Based on prior literature, scores of four or greater were considered problematic mobile phone use [38].

Covariates

Parents reported participants’ age, sex (male or female) and race/ethnicity (White, Black, Native American, Latino/Hispanic, Asian, or Other) at baseline. Parents also reported highest parent education (high school or lower versus college or higher) and household income (less than $25,000, $25,000 - $50,000, $50,000 - $75,000, $75,000 - $100,000, $100,000 - $200,000, and greater than $200,000) at baseline Depressive, anxious, and attention-deficit symptoms at baseline were generated from parent/caregiver responses to the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), a screening tool that asks a parent/caretaker about multiple psychiatric symptoms and behavior problems in children ages 4–18 [20, 39]. We included t scores of depressive, anxious, and attention-deficit scales from the CBCL. CBCL raw scores for each scale were converted to norm-referenced t-scores (mean = 50, standard deviation 10). Separate norms were provided for gender across age groups [40]. These psychiatric symptoms were included because extensive literature establishes the relationship between ACEs and adolescent depression, anxiety, and ADHD [41, 42], and these mental health conditions have been associated with higher levels of problematic screen use [43] and have been included in similar analyses [17, 44]. Study site and twins were noted.

Statistical analyses

Generalized logistic mixed effects models estimated prospective associations between baseline ACE score and problematic video game, social media, and mobile phone use (binary outcomes) among youth who reported that type of screen use. In our supplemental analyses, generalized linear effects models estimated prospective associations between baseline ACE score and problematic use scores. To account for missing data in both models, we performed multiple imputation by chained equations using the R package “mice”. There were missing data including twins, 3 (0.04%); gender, 5 (0.07%); race, 33 (0.4%); depression, 1955 (25.7%); anxiety, 1955 (25.7%); and ADHD, 1955 (25.7%). Because our primary interest is the point estimates, we imputed 10 datasets and pooled the estimates from each dataset [45,46,47]. Supplemental Fig. 1 highlights adolescent represents included in each analysis. The supplemental analysis estimates prospective associations with continuous problematic screen use scales. Both analyses were adjusted for potential confounders listed above, accounting for study cite and twins Analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.2. Given the potential overlap between outcome variables, a correlation matrix is shown in the appendix (Supplemental Table 2).

Results

The sample of 9,673 adolescents was racially and ethnically diverse (52.9% White, 17.4% Latino/Hispanic, 19.4% Black, 5.8% Asian, 3.7% Native American, 0.9% Other; Table 1). Participants mean age was 12.0 years old (SD 0.7, range 10.6–14). Among adolescents who used screens, 7% reported problematic video game use, 3.5% reported problematic social media use, and 21.8% reported problematic mobile phone use.

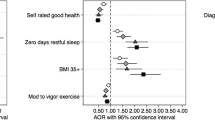

In both the unadjusted and adjusted models, among youth who reported screen use, a higher ACE score was associated with a higher odds of problematic video game and mobile phone use. In the adjusted models, an ACE score of four or more was associated with 3.1 and 1.6 times higher odds of having problematic video game use and mobile phone use, respectively ACE score was associated with problematic video game use in a dose dependent manner. Figure 1 highlights how increasing ACE score was associated with greater rates of problematic video game and mobile phone use (Table 2). There was no statistical association between problematic social media use and ACE score. However, a higher ACE score was also associated with higher survey scores of problematic video game, media, and phone use(Supplemental Tables 3, Supplemental Fig. 2).

Discussion

This large, demographically diverse, national sample of 9,673early adolescents who use screens found that a greater ACE score was significantly associated with greater problematic video game and mobile phone use (when problematic screen use was measured as a binary outcome). Youth exposed to 4 or more ACEs experienced 3.1 times higher odds of reported problematic video game use and 1.6 times higher odds of problematic mobile phone use compared to peers with no ACEs. Given that behavioral addictions can have significant negative personal, social, and professional impacts, understanding risk factors to their development is critical.

Increased rates of problematic screen use among a nationally representative study of U.S. screen-using youth with higher ACE scores builds upon prior findings. Previous studies have shown that ACEs are associated with higher video game use among Japanese adolescents [14] and Chinese university students [13] and higher mobile phone addiction in Chinese university students [18]. In addition, a 2019 study of exclusively high-risk U.S. youth found a dose-dependent relationship between ACEs and problematic media use using parent-report data [16]. This study builds upon these prior findings by using youth self-report data and showing that ACEs are an important risk factor for problematic screen use among a demographically diverse sample of U.S. early adolescents. Our study further contributes to the literature by focusing on early adolescents, who represent a critical age group because this developmental period is vulnerable to developing health-related risk factors [1, 48]. This study also found that problematic social media use, a contemporary, novel measure associated with adverse physical and mental health consequences, was not associated with ACEs in the logistic model (Table 2), though a dose-dependent relationship was observed in the linear model (Supplemental Table 3) [49, 50] It is important to note for these mixed results that rates of problematic social media use were low at3.5%, which may be due to relative younger age of the participants in our study (11–12 years old). Accordingly, it is important to continue to examine the association between ACEs and problematic screen-use in a broader sample of adolescents of older ages, during which time social media use – and the possibility of problematic social media use – may be elevated.

This study found that 7.0% of US adolescents who used screens endorsed problematic video game use and 21.8% reported problematic phone use. These rates are similar than prior studies that have found that 7.6% of German adolescents report video game addiction [51] and 22.9% of Chinese adolescents report problematic phone use; however, as our study excluded youth who did not report screen use, the true average use is likely lower; we suspect may be partially secondary to the lower average age in the ABCD cohort (11–12 years). The high rates of problematic mobile phone use, approaching one in four early adolescents, is concerning for early education around mobile phone use and behaviors.

Limitations to this study include vulnerability to confounding variables; however, given the breadth of the ABCD cohort measures we did include many covariates (sex, race/ethnicity, income, parent education, mental health conditions). In addition, the ABCD dataset does not include a single, validated scale, so this score was generated from questions across different surveys capturing the same themes as the original ACEs screener. Therefore, future research should reassess the questions posed in this study using such a scale. In addition, we analyzed data from youth who reported screen use, so findings cannot be generalized to all adolescents regardless of screen use. Also, cutoff scores for the VGAQ and SMAQ have not been clearly established in the literature and were extrapolated conservatively from the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale. Finally, mobile phone and social media behavior may have areas of overlap (Supplemental Table 3) [52].

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that, among adolescents who use screens, higher ACE scores are associated with problematic screen use, particularly problematic video game and mobile phone use, which has important clinical and public policy implications for screen time recommendations. For example, clinicians should be aware of the increased risk of problematic screen use among youth with high ACE scores, explore video game, social media, and mobile phone use among this population, and collaborate with families to implement a family media use plan informed by the American Academy of Pediatrics [53]. In addition, schools may consider implementing curricula focused on promoting healthy digital habits [54]. Future studies should explore protective factors to problematic video game, social media, and mobile phone use among ACE-exposed adolescents and the effectiveness of clinic-based interventions for this population.

Data Availability

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the ABCD Study (https://abcdstudy.org), held in the NIMH Data Archive (NDA). Investigators can apply for data access through the NDA (https://nda.nih.gov/).

Abbreviations

- ACEs:

-

Adverse Childhood Experiences

- ABCD study:

-

Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development

- VGAQ:

-

Video Game Addiction Questionnaire

- SMAQ:

-

Social Media Addiction Questionnaire

- MPIQ:

-

Mobile Phone Involvement Questionnaire

References

Anderson M, Jiang J, Teens SM. & Technology 2018 [Internet]. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 2018 [cited 2022 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/.

Gros L, Debue N, Lete J, van de Leemput C. Video Game Addiction and Emotional States: possible confusion between pleasure and happiness? Front Psychol. 2020 Jan 27;10:2894.

Griffiths M. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J Subst Use. 2005 Jan 1;10(4):191–7.

Nagata JM, Singh G, Sajjad OM, Ganson KT, Testa A, Jackson DB et al. Social epidemiology of early adolescent problematic screen use in the United States. Pediatr Res 2022 Jun 29;1–7.

Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Social networking Sites and Addiction: ten Lessons learned. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 Mar;14(3):311.

Haug S, Castro RP, Kwon M, Filler A, Kowatsch T, Schaub MP. Smartphone use and smartphone addiction among young people in Switzerland. J Behav Addict 4(4):299–307.

Turkle S. Alone together: why we expect more from technology and less from each other. 360xvii, p. ed. New York, NY, US: Basic Books; 2011. (Alone together: why we expect more from technology and less from each other).

Fiechtner L, Fonte ML, Castro I, Gerber M, Horan C, Sharifi M et al. Determinants of Binge Eating Symptoms in Children with Overweight/Obesity. Child Obes. 2018 Dec 1;14(8):510–7.

Andrade JL, Hong YR, Lee AM, Miller DR, Williams C, Thompson LA, et al. Adverse childhood experiences are Associated with Cardiometabolic Risk among hispanic american adolescents. J Pediatr. 2021 Oct;1:237:267–275e1.

Nagata JM, Chu J, Zamora G, Ganson KT, Testa A, Jackson DB et al. Screen Time and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Among Children 9–10 Years Old: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Adolesc Health [Internet]. 2022 Dec 12 [cited 2022 Dec 13]; Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1054139X22007224.

Giordano GN, Ohlsson H, Kendler KS, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Unexpected adverse childhood experiences and subsequent drug use disorder: a swedish population study (1995–2011). Addict Abingdon Engl. 2014 Jul;109(7):1119–27.

Puetz VB, McCrory E. Exploring the relationship between Childhood Maltreatment and Addiction: a review of the neurocognitive evidence. Curr Addict Rep. 2015;2(4):318–25.

Shi L, Wang Y, Yu H, Wilson A, Cook S, Duan Z et al. The relationship between childhood trauma and Internet gaming disorder among college students: A structural equation model. J Behav Addict. 2020 Apr 7;9(1):175–80.

Doi S, Isumi A, Fujiwara T. Association between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Time Spent Playing Video Games in Adolescents: Results from A-CHILD Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Oct 2;18(19):10377.

Yates TM, Gregor MA, Haviland MG. Child maltreatment, Alexithymia, and problematic internet use in Young Adulthood. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw. 2012 Apr;15(4):219–25.

Domoff SE, Borgen AL, Wilke N, Hiles Howard A. Adverse childhood experiences and problematic media use: perceptions of caregivers of high-risk youth. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jun;22(13):6725.

Jackson DB, Testa A, Fox B. Adverse childhood Experiences and Digital Media Use among U.S. children. Am J Prev Med. 2021 Apr;60(4):462–70.

Li W, Zhang X, Chu M, Li G. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on Mobile phone addiction in Chinese College students: a serial multiple mediator model. Front Psychol. 2020 May;13:11:834.

Auxier B, Anderson M, Perrin A, Turner E. 1. Children’s engagement with digital devices, screen time [Internet]. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 2020 [cited 2022 Jun 17]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/07/28/childrens-engagement-with-digital-devices-screen-time/.

Barch DM, Albaugh MD, Avenevoli S, Chang L, Clark DB, Glantz MD et al. Demographic, physical and mental health assessments in the adolescent brain and cognitive development study: rationale and description. Dev Cogn Neurosci 2017 Nov 3;32:55–66.

Chu J, Raney JH, Ganson KT, Wu K, Rupanagunta A, Testa A et al. Adverse childhood experiences and binge-eating disorder in early adolescents. J Eat Disord. Forthcoming.

Nagata JM, Trompeter N, Singh G, Raney J, Ganson K, Testa A et al. Adverse childhood experiences and early adolescent cyberbullying in the United States. J Adolesc. Forthcoming.

Hoffman EA, Clark DB, Orendain N, Hudziak J, Squeglia LM, Dowling GJ. Stress exposures, neurodevelopment and health measures in the ABCD study. Neurobiol Stress. 2019 Mar;19:10:100157.

Lewis-de los Angeles WW. Association between adverse childhood Experiences and Diet, Exercise, and Sleep in pre-adolescents. Acad Pediatr. 2022 Nov;22(1):1281–6.

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V et al. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998 May 1;14(4):245–58.

Briggs EC, Amaya-Jackson L, Putnam KT, Putnam FW. All adverse childhood experiences are not equal: the contribution of synergy to adverse childhood experience scores. Am Psychol. 2021 Mar;76(2):243–52.

Andreassen CS, TorbjØrn T, Brunborg GS, Pallesen S. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychol Rep. 2012 Apr;110(2):501–17.

Ali AM, Hendawy AO, Abd Elhay ES, Ali EM, Alkhamees AA, Kunugi H et al. The Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale: its psychometric properties and invariance among women with eating disorders. BMC Womens Health 2022 Mar 31;22:99.

Ghali H, Ghammem R, Zammit N, Fredj SB, Ammari F, Maatoug J et al. Validation of the arabic version of the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale in tunisian adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2019 Sep 24;34(1).

Phanasathit M, Manwong M, Hanprathet N, Khumsri J, Yingyeun R. Validation of the Thai version of Bergen Facebook addiction scale (Thai-BFAS). J Med Assoc Thail Chotmaihet Thangphaet. 2015 Mar;98(Suppl 2):108–17.

Bagot K, Tomko R, Marshall AT, Hermann J, Cummins K, Ksinan A, et al. Youth screen use in the ABCD® study. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2022 Sep;1:57:101150.

Luo T, Qin L, Cheng L, Wang S, Zhu Z, Xu J, et al. Determination the cut-off point for the Bergen social media addiction (BSMAS): diagnostic contribution of the six criteria of the components model of addiction for social media disorder. J Behav Addict. 2021 Jul;10(2):281.

Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, Pallesen S. Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychol Rep. 2012 Apr;110(2):501–17.

Simsek A, Elciyar K, Kizilhan T. A comparative study on Social Media Addiction of High School and University students. Contemp Educ Technol 2019 Apr 16;10(2):106–19.

Hou Y, Xiong D, Jiang T, Song L, Wang Q. Social media addiction: Its impact, mediation, and intervention. Cyberpsychology J Psychosoc Res Cyberspace [Internet]. 2019 Feb 21 [cited 2022 Jun 14];13(1). Available from: https://cyberpsychology.eu/article/view/11562.

Walsh SP, White KM, McD Young R. Needing to connect: the effect of self and others on young people’s involvement with their mobile phones. Aust J Psychol. 2010 Dec;62(1):194–203.

Mrazek AJ, Mrazek MD, Ortega JR, Ji RR, Karimi SS, Brown CS et al. Teenagers’ Smartphone Use during Homework: An Analysis of Beliefs and Behaviors around Digital Multitasking. Educ Sci [Internet]. 2021 Nov 5 [cited 2022 Jun 14]; Available from: https://www.scinapse.io.

Lin L, Xu X, Fang L, Xie L, Ling X, Chen Y, et al. [Validity and reliability of the chinese version of Mobile phone involvement questionnaire in college students]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2020 May;30(5):746–51.

Achenbach TM, Ruffle TM. The child Behavior Checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatr Rev. 2000 Aug;21(8):265–71.

Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment. In: Volkmar FR, editor. Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders [Internet]. New York, NY: Springer; 2013 [cited 2022 Oct 19]. p. 31–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1698-3_219.

Elmore AL, Crouch E. The Association of adverse childhood experiences with anxiety and depression for children and Youth, 8 to 17 years of age. Acad Pediatr. 2020 Jul;20(5):600–8.

Tsehay M, Necho M, Mekonnen W. The role of adverse childhood experience on Depression Symptom, Prevalence, and severity among School going adolescents. Depress Res Treat. 2020 Mar 18;2020:5951792.

Mentzoni RA, Brunborg GS, Molde H, Myrseth H, Skouverøe KJM, Hetland J, et al. Problematic video game use: estimated prevalence and associations with mental and physical health. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw. 2011 Oct;14(10):591–6.

Forster M, Rogers CJ, Sussman S, Watts J, Rahman T, Yu S, et al. Can adverse childhood experiences heighten risk for problematic internet and smartphone use? Findings from a College Sample. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jun;2(11):5978.

van Buuren S. Flexible Imputation of Missing Data, Second Edition. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2018. 444 p.

Frontmatter. In: Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys [Internet]. John Wiley, Sons L. ; 1987 [cited 2023 May 11]. p. i–xxix. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9780470316696.fmatter.

Stuart EA, Azur M, Frangakis C, Leaf P. Multiple imputation with large data sets: a case study of the children’s Mental Health Initiative. Am J Epidemiol. 2009 May;169(1):1133–9.

Dahl RE, Allen NB, Wilbrecht L, Suleiman AB. Importance of investing in adolescence from a developmental science perspective. Nature. 2018 Feb;554(7693):441–50.

Nagata JM, Cortez CA, Cattle CJ, Ganson KT, Iyer P, Bibbins-Domingo K et al. Screen Time Use Among US Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings From the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. JAMA Pediatr [Internet]. 2021 Nov 1 [cited 2021 Nov 13]; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4334.

Nagata JM, Iyer P, Chu J, Baker FC, Gabriel KP, Garber AK, et al. Contemporary screen time usage among children 9-10-years-old is associated with higher body mass index percentile at 1-year follow-up: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Obes. 2021 Dec;16(12):e12827.

Festl R, Scharkow M, Quandt T. Problematic computer game use among adolescents, younger and older adults. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2013 Mar;108(3):592–9.

Brunette MF, Achtyes E, Pratt S, Stilwell K, Opperman M, Guarino S, et al. Use of smartphones, computers and social media among people with SMI: opportunity for intervention. Community Ment Health J. 2019 Aug;55(6):973–8.

Korioth T, Writer S. Family Media Plan helps parents set boundaries for kids. 2016 Oct 21 [cited 2022 Jun 17]; Available from: https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/9082/Family-Media-Plan-helps-parents-set-boundaries-for.

Nesi J, Telzer EH, Prinstein MJ, editors. Intervention and Prevention in the Digital Age. In: Handbook of Adolescent Digital Media Use and Mental Health [Internet]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2022. p. 363–416. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/handbook-of-adolescent-digital-media-use-and-mental-health/intervention-and-prevention-in-the-digital-age/D77E9863992E4A6AE3585E1E9988AA5E.

Acknowledgements

The ABCD Study was supported by the Nacional Institutes of Health and additional federal partners under award numbers U01DA041022, U01DA041025, U01DA041028, U01DA041048, U01DA041089, U01DA041093, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041120, U01DA041134, U01DA041148, U01DA041156, U01DA041174, U24DA041123, and U24DA041147. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/federal-partners/. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/principal-investigators.html. ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in the analysis or writing of this report.

Funding

J.M.N. was funded by the National Institutes of Health (K08HL159350), the American Heart Association Career Development Award (CDA34760281), and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (2022056). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H.R. was responsible for the co-development of the research study design, methods, and data analysisand methods; she also drafted the initial manuscript. A.A. co-developed the methods and formal analysis and completed the formal analysis. K.T.G, A.T., and D.B.J. co-developed the study design, methods, and formal analysis; they also provided oversight and participated in the revision of the manuscript. G.S and O.M.S. completed the data cleaning and critically reviewed the manuscript. J.M.N provided supervision; he also co-developed the conceptualization of the study, methods, and supported the analysis and manuscript revision. All authors approved the final submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent and assent were obtained from the parent/guardian and adolescent, respectively, to participate in the ABCD Study. The University of California, San Diego provided centralized institutional review board (IRB) approval and each participating site received local IRB approval:

• Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California.

• Florida International University, Miami, Florida.

• Laureate Institute for Brain Research, Tulsa, Oklahoma.

• Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina.

• Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon.

• SRI International, Menlo Park, California.

• University of California San Diego, San Diego, California.

• University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California.

• University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado.

• University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

• University of Maryland at Baltimore, Baltimore, Maryland.

• University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

• University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

• University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

• University of Rochester, Rochester, New York.

• University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah.

• University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont.

• University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

• Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia.

• Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri.

• Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Raney, J.H., Al-shoaibi, A.A., Ganson, K.T. et al. Associations between adverse childhood experiences and early adolescent problematic screen use in the United States. BMC Public Health 23, 1213 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16111-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16111-x