Abstract

Background

Individuals experiencing homelessness (IEHs) suffer from severe health inequities. Place of origin is linked to health and mortality of IEHs. In the general population the “healthy immigrant effect” provides a health advantage to foreign-born people. This phenomenon has not been sufficiently studied among the IEH population. The objectives are to study morbidity, mortality, and age at death among IEHs in Spain, paying special attention to their origin (Spanish-born or foreign-born) and to examine correlates and predictors of age at death.

Methods

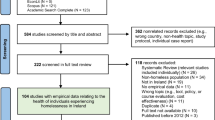

Retrospective cohort study (observational study) of a 15-year period (2006–2020). We included 391 IEHs who had been attended at one of the city’s public mental health, substance use disorder, primary health, or specialized social services. Subsequently, we noted which subjects died during the study period and analyzed the variables related to their age at death. We compared the results based on origin (Spanish-born vs. foreign-born) and fitted a multiple linear regression model to the data to establish predictors of an earlier age at death.

Results

The mean age at death was 52.38 years. Spanish-born IEHs died on average almost nine years younger. The leading causes of death overall were suicide and drug-related disorders (cirrhosis, overdose, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]). The results of the linear regression showed that earlier death was linked to COPD (b = − 0.348), being Spanish-born (b = 0.324), substance use disorder [cocaine (b =-0.169), opiates (b =.-243), and alcohol (b =-0.199)], cardiovascular diseases (b = − 0.223), tuberculosis (b = − 0.163), high blood pressure (b =-0.203), criminal record (b =-0.167), and hepatitis C (b =-0.129). When we separated the causes of death for Spanish-born and foreign-born subjects, we found that the main predictors of death among Spanish-born IEHs were opiate use disorder (b =-0.675), COPD (b =-0.479), cocaine use disorder (b =-0.208), high blood pressure (b =-0.358), multiple drug use disorder (b =-0.365), cardiovascular disease (b =-0.306), dual pathology (b =-0.286), female gender (b =-0.181), personality disorder (b =-0.201), obesity (b =-0.123), tuberculosis (b =-0.120) and having a criminal record (b =-0.153). In contrast, the predictors of death among foreign-born IEHs were psychotic disorder (b =-0.134), tuberculosis (b =-0.132), and opiate (b =-0.119) or alcohol use disorder (b =-0.098).

Conclusions

IEHs die younger than the general population, often due to suicide and drug use. The healthy immigrant effect seems to hold in IEHs as well as in the general population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Individuals experiencing homelessness (IEHs) suffer from severe inequities in a wide range of biological, psychological, and social conditions [1]. As a result, IEHs have a lower life expectancy [2]. One of the most accepted explanations for the high mortality of IEHs is that they are subject to an accumulation of risk factors such as drug use (including tobacco and alcohol) and mental health problems [3]. In addition, IEHs are particularly vulnerable to death from injury, overdose, and other external causes [4, 5], and from cardiovascular and respiratory conditions [1]. Moreover, they are more likely to suffer from infections (especially hepatitis and tuberculosis). Treatment of active tuberculosis in IEHs can be complicated by nonadherence to therapy, prolonged infectivity, and the development of drug resistance [6]. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is also more prevalent in this population. Common risk factors for HIV infection among IEHs include prostitution, multiple sexual partners, inconsistent use of condoms, and injection drug use [7].

There are subgroups of IEHs whose specific characteristics imply differentiated risk factors and causes of mortality. The death of young IEHs is associated with external causes, especially suicide and overdose [8], while death in adult IEHs is associated with diseases typical of the general population. However, the age at death among IEH adults is between 10 and 15 years lower than that of the general adult population, according to the study by Baggett et al. [2] or 20 years lower, according to that by Termorshuizen et al. [9].

Another specific population to consider when establishing differences in health, especially in mental health, is the foreign-born population. Studies on foreign-born IEHs have reported a health advantage for immigrants experiencing homelessness compared to people born in the country [10,11,12]. This advantage has to do with greater youth, a better state of general health (since, given the difficulties of migration, people who migrate tend to be healthier than the general population in their home country) and that the causes of homelessness differ from that of locally born populations and are more related to poverty and migration [13]. Foreign-born people—especially recent immigrants—are less likely to suffer from chronic health problems, mental health problems and/or substance use disorder [14].

Studies carried out with the general population show that migration increases the risk of homelessness and has a negative impact on health. In the general population, worse mental health has been reported in people who have migrated, as a result of the associated stress [15]. In contrast, migration is associated with better health during the first ten years of residence in the receiving country compared to locally born people [16]. Studies carried out in Canada show a higher age at death among foreign-born people compared to those born in the country. This advantage is less clear for morbidity, especially if migration occurs during adulthood and not in the perinatal period, childhood/adolescence or at the end of life [17, 18]. In Europe, there are North-South differences in the health status of immigrants compared to those born in the receiving country, which are partly explained by the poorer economic and social conditions of immigrants in some countries. Their state of health is better in Italy and Spain than in France and Belgium, where there are greater difficulties surrounding integration [19].

In Spain, the differences in the health of foreign-born individuals with respect to Spanish-born individuals depend on socioeconomic factors such as poverty and socioeconomic status. Gotsens et al. found that foreign-born born people who arrived before 2006 had worse self-rated health than locally born people, despite the fact that the latter group had a higher prevalence of disability, illness, and mental disorders. On the other hand, foreign-born people who arrived after 2006 had better mental health than Spanish-born people. These advantages tended to be diluted by the effect of the economic crisis that began in 2008 [20]. The health advantages in foreign-born people can occur even a generation later, with children born in the receiving country to foreign-born parents experiencing better health than the children of locally born parents [21].

There is a gap in the scientific literature on the effect of migration on the health of IEHs. In Spain, we especially need studies to analyze this effect, as well as its relationship with health and mortality since in some areas the foreign-born IEH population represents more than half of the total IEH population [22]. Such a study in Spain is also important because, due to its geographical location, Spain is a point of entry for thousands of people who migrate to other European countries. The few studies carried out in Spain confirm an advantage in the health of immigrant IEHs [23], especially newcomers [10], but this phenomenon has still not been sufficiently studied. Thus, the objectives of this study were: (1) To study the mortality and age at death among IEHs in Spain; (2) To compare the age at death and its characteristics among people of IEHs in relation to their origin (Spanish-born or foreign-born); (3) To examine correlates and predictors of age at death.

Method

Design

A retrospective cohort study (observational study) of a 15-year period.

Population under study

We included the 391 IEHs that died between 2006 and 2020 (both included) and that had been attended by one of the city of Girona (Spain)’s public mental health, substance use disorder, primary health, or specialized social services (day center, overnight shelter, or street team). All of the subjects met the criteria for literal homelessness, i.e., people living in public space or whose overnight housing situation forces them to spend the day on the streets or in situations of extreme substandard housing (European Homelessness Observatory categories 1, 2, 3d, 3e, 3f and 3 h of homelessness and residential exclusion) (Busch-Geertsema et al., 2016). These categories refer to: (i) people without accommodation, sleeping on the streets, in public space, in vehicles or under some form of makeshift cover; (ii) persons living in any type of temporary or crisis accommodation; (iii) persons illegally occupying conventional housing; (iv) persons living in conventional dwellings unfit for human habitation; (v) persons living in trailers, tents or caravans; and (vi) persons living in non-conventional buildings and temporary structures or settlements.

Procedure

Some members of the research team in this study were clinicians from mental health and addiction services in Girona and also from social services at the time of data recruitment. They were part of a multidisciplinary community team coordinated to address the needs of homeless patients in a comprehensive manner. The patients, before being attended in any of these services, signed an informed consent form in which they accepted the coordination of the professionals of the different services for better social and health care. The professionals of this team, between 2006 and 2020, attended 3,854 homeless people. Thanks to the coordination of health and social services, a shared list of cases with social, mental health, addictions and mortality data was obtained, which identified 391 people who had died during these years.

The research team obtained permission from the Ethics Committee of the Institut d’Assistència Sanitària (CIEC-IAS), Catalan Institute of Health, with the code Estudi_homeless_2008 on December 12, 2014. And also that of the Research Ethics Committee CEI GIRONA that renewed the permission on October 28, 2016 with the project name Evolució homeless de Girona: Seguiment longitudinal Cohort 2006/2016 (Code COHORT2006). As it was not possible to obtain informed consent for research purposes, the Ethics Committee approved the permission for the study in accordance with the exceptions included In articles 7 and 11 of the Organic Law 15/1999 on the Protection of Personal Data. The ethics committee approved the study while this law was in force. In 2018, Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights, came into force, which modified the previous law authorizing the present study. The new law, in its sixth transitory provision on the reuse for health and biomedical research purposes of personal data collected prior to the entry into force of this organic law states: The reuse for health and biomedical research purposes of personal data lawfully collected prior to the entry into force of this organic law shall be considered lawful and compatible when any of the following circumstances concur: (a) That such personal data are used for the specific purpose for which consent had been given. (b) That, having obtained consent for a specific purpose, such data are used for purposes or areas of research related to the medical or research specialty in which the initial study was scientifically integrated.

The same ethics committee, which is the reference ethics committee of the public health services of the province of Girona, annually renews the permission to continue analyzing the data of the cohort on which this study is based according to the Spanish legality reflected in this text. Therefore, the permission to proceed with research using this database is currently in force, in compliance with Spanish law. The renewal code of the permit is dated January 10, 2023 with the renewal code COHORT_2016.133.

Additional Provision 17.2.d LOPD-GDD on pseudo-anonymization of personal data was also followed. To meet this criterion, the research team provided an administrative team with the list of homeless people with their health data (data used in the clinical follow-up of the patients) and the administrative team rearranged the database and assigned a random, anonymous code to each person so that the research team had no record of the person’s identity. The data were then analyzed and used in an aggregated, anonymous and confidential manner.

We included these basic sociodemographic variables: age, gender, marital status, criminal record or prison sentence, and origin. For origin, subjects were identified as Spanish-born or foreign-born, where the former were people born within the national territory of the Spanish state and the latter were people born outside the Spanish state. We define origin is an invariable status that is determined by the individual’s country of birth, regardless of the individual’s citizenship or the immigration status of the individual’s parents or grandparents [24, 25].

We studied variables related to (a) mental health and addiction: having an open medical record in the mental health and addiction network, main diagnosis of substance use disorder, main diagnosis of other mental disorder (eating disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, sleep disorder, phobia, behavioral disorder and nonspecific disorder) and dual pathology; (b) clinical diagnosis of infection: hepatitis C virus, HIV and tuberculosis; (c) clinical diagnosis of chronic physical disease: arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D), COPD, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and cancer; and (d) clinical and diagnostic mortality: living/deceased, age at death and cause of death. We composed a list of the people who died during the analysis period and analyzed the variables related to the age at death.

Statistical analysis

Measures of central tendency and dispersion were used to describe the numerical variables and the absolute and relative frequencies were calculated in the case of categorical variables. We used a Student’s t-test to compare means and a chi-square test to analyze categorical variables. A multiple linear regression model was fitted to the data to establish the predictors of an earlier age at death, after checking the assumption of normality in the distribution of the data (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test), independence of residual values (Durbin-Watson test), collinearity (tolerance and variance inflation factor) and homogeneity of the variance between Spanish-born and foreign-born IEHs (Levene’s test). We included variables related to a lower age at death in the bivariate analysis.

Results

The cause of death for eight IEHs could not be established, and therefore they were eliminated from the mortality analysis. Thus, the analysis was carried out on 383 people, of which 281 were Spanish-born and 102 foreign-born. The leading cause of death was suicide (n = 92), followed by cirrhosis of the liver (n = 70), overdose (n = 58), COPD (n = 42), heart disease/infarction (n = 36), acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) (n = 36), cancer (n = 36), meningitis (n = 31) and sepsis (n = 18).

Variables associated with age at death

The mean age at death of the 383 people was 52.38 years (SD = 13.23; range 22–89). Table 1 shows that the Spanish-born IEHs died younger (M = 48.65 years) than the foreign-born IEHs (M = 57.82 years, t(382) = 1.476, p < .001). People with a criminal record also died earlier than people who had no criminal record (50.87 years vs. 59.00 years, t(124) = -2.655, p = .009).

With respect to mental health diagnoses related to substance use disorder, people with alcohol use disorder died earlier (51.20 years vs. 56.80 years, t(129) = -3.505, p = .001), as did people with opiate use disorder (44.87 years vs. 53.01 years, t(382) = -3.277, p = .001) and cocaine use disorder (44.50 years vs. 52.46 years, t(382) = -1.198, p < .001) (see Table 1). No significant differences were found in the age at death for the rest of the mental health disorders, whether related to substance use disorder or not.

In terms of infections, mean differences in the age at death were found in all of infection variables: hepatitis C (48.32 years vs. 52.97 years, t(382)= -2.911, p = .009), HIV (49.88 years vs. 53.39 years, t(382)= -2.9387, p = .017) and tuberculosis (49.12 years vs. 53.91 years, t(382)= -2.077, p = .021) (see Table 1). Finally, regarding chronic organic diseases (see Table 1), differences were found in the age at death in people diagnosed with arterial hypertension (50.73 years vs. 61.43 years, t(75.4)= -5.391, p < .001), T2D (51.67 years vs. 57.42 years, t(63.8) = -3.037, p = .003), cardiovascular disease (51.54 years vs. 58.12 years, t(58.7)= -2.841, p = .006), COPD (51.41 years vs. 61.32 years, t(382) = -4.489, p < .001) and cancer (51.95 years vs. 56.78 years, t(43.4) = -2.168, p = .036).

Predictors of a lower age at death

Before performing the multiple linear regression, we tested for normal distribution of the variable age at death (Kolmogorov-Smirnov = 1.171, p = .129), independence of the residual values (Durbin-Watson = 1.877), and collinearity (tolerance = 0.894, variance inflation factor = 1.231). The results of the linear regression with deceased persons (see Table 2) showed a link to age at death for COPD (b = − 0.348), not being foreign-born (b = 0.324), cocaine use disorder (b = − 0.169), opiate use disorder (b = − 0.243), cardiovascular disease (b = − 0.223), alcohol use disorder (b = − 0.199), tuberculosis (b = − 0.163), HA (b = − 0.203), criminal record (b = − 0.167) and hepatitis C (b = − 0.129). The variables included in the model explained 89% of the variance in the age at death.

Given the weight of the Spanish-born/foreign-born variable, two separate linear regression models were fitted to the data to observe the differences in the age at death in relation to the predicting variables, one for the Spanish-born IEH subjects and the other for the foreign-born IEH subjects. Regarding the Spanish-born IEHs (see Table 3), the regression showed the following predictors of the age at death: opiate use disorder (b = − 0.675), COPD (b = − 0.479), cocaine use disorder (b = − 0.208), arterial hypertension (b = − 0.358), multiple drug use disorder (b = − 0.365), cardiovascular disease (b = − 0.306), dual pathology (b = − 0.286), female gender (b = − 0.181), personality disorder (b = − 0.201), obesity (b = − 0.123), tuberculosis (b = − 0.120), and criminal record (b = − 0.153). The variables included in this model explained 87% of the variance in the age at death of Spanish-born people. Regarding the foreign-born IEHs, linear regression showed the following predictors of age at death: psychotic disorder (b = − 0.134), tuberculosis (b = − 0.132), opiate use disorder (b = − 0.119) and alcohol use disorder (b = − 0.098) (see Table 4). In this case, the variables included in the model explained 78% of the variance in the age at death of foreign-born people.

Discussion

We analyzed mortality and age at death among IEHs in Spain, comparing Spanish-born individuals and foreign-born individuals. The leading cause of death among the sample was suicide, but cirrhosis, overdose, and COPD were also major causes of death. Notably, one in four deaths was by suicide. Suicide is a serious, global public health issue worldwide and its prevention has been included in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [26]. Given that suicide is markedly prevalent among IEHs [27, 28], the reduction of suicide mortality should be a priority in this population. Care should be taken to ensure that suicide prevention programs reach IEHs. In this sense, providing a telephone and Wi-Fi service to IEHs could help them access basic and specialized health services [29, 30], considering the good results of self-harm prevention lines [31] and the existence of this type of program in Spain [32].

Cirrhosis was the second leading cause of death. Several studies show the high prevalence of chronic liver disease in IEHs, compared to the general population, mainly due to chronic hepatitis C infection and alcohol abuse [33]. Hepatitis C is almost five times more prevalent in IEHs. The effectiveness of new treatments has dramatically reduced the incidence and complications of chronic hepatitis C infection in developed countries and today, hepatitis C is concentrated in hard-to-treat populations, such as IEHs. Homelessness or unstable housing hinders the success of hepatitis C treatment. Adherence could be improved by dispensing antivirals in health facilities and observing patients as they take them, either in facilities or on the street (in the latter case, by teams of street social workers/educators) [34].

Another striking finding was that the mean age at death was 52 years. This age is drastically lower than that recorded for the Spanish general population, which is estimated at 83 years [35]. Disorders related to alcohol, opiates, and cocaine use clearly influenced earlier age of death, as did hepatitis C, HIV, tuberculosis, and several chronic conditions (e.g., arterial hypertension, T2D, COPD, cardiovascular disease, etc.). These results are in accordance with previous studies indicating that IEHs experience high rates of morbidity, mortality, and premature death [2, 23, 36, 37].

Concerning predictors of age at death, and in line with other studies, the largest differences in mortality rates were for smoking-related diseases: respiratory diseases and ischemic heart disease [38]. The strongest predictor across the whole sample was the occurrence of COPD. COPD is particularly prevalent among IEH adults, and respiratory tract infections are common in this group [7, 36]. The prevalence of COPD in IEHs is probably underestimated, given the difficulty of these patients to receive complementary tests, such as spirometry, to confirm the diagnosis. The handling and proper use of inhalers is also complex, hampered by the sometimes high price of inhalers and the frequent loss of both medicines and inhalation chambers. IEHs’ poor oral health and missing teeth can cause an improper fit of the chamber and therefore a loss of effectiveness. The use of Beta 2 adrenergic drugs, such as salbutamol, can create substance use disorder in these patients, and tachycardia, produced as a side effect, can worsen previous cardiovascular disease.

The approach to smoking in this population deserves a special attention. In clinical practice, we often find IEHs who have smoked since childhood or adolescence and who consume more than one pack a day. IEHs use the cheapest cigarette brands, which are especially rich in tar and nicotine. They may reuse cigarettes by collecting cigarette butts and use newspaper as rolling paper, thus increasing their exposure to infection and toxins [39]. Tobacco is not the only substance they may consume in this way. Marijuana, smoked or snorted cocaine, and volatile substances also affect the lungs over time [40]. Traditionally, professionals from health and mental health services have tended to tolerate tobacco consumption in IEHs, considering it a lesser evil among the substance use disorders and pathologies they present [41]. In fact, some professionals have been reported to offer IEHs cigarettes as a way of establishing rapport [42]. These actions should be abandoned and, given the high mortality and years of life lost due to smoking in the IEH population, specific programs should be designed to support IEH smokers who want to quit. In fact, there are no differences between IEHs and the general population when it comes to quitting smoking [43], and IEHs can benefit from the usual strategies aimed at smokers in the general population, such as helping them to increase their perception of self-efficacy and their social support [44]. IEHs face substantial barriers to quitting smoking, and there is still insufficient evidence to assess the effects of tobacco cessation interventions in the IEH population [45]. Although tobacco use disorder disproportionately affects disadvantaged groups, they are often underrepresented in medical research and treatments [46]. It is essential to maximize enrollment and retention strategies adapted to IEHs.

The presence of cardiovascular disease was another predictor of death. IEHs have an approximately three times greater risk of cardiovascular disease and an increased cardiovascular mortality than the general population [47]. Several factors contribute to this disparity. In addition to the high prevalence of smoking, there is poor monitoring of cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes. Psychosocial factors such as chronic stress, depression and substance use disorder use confer an additional risk of poor monitoring and adverse effects. Poor access to medical care leads to delays in diagnosis and treatment. Multidisciplinary collaboration between healthcare professionals and social workers is necessary for success in managing IEHs with chronic cardiovascular disease [48].

Additionally, separate regression models for Spanish-born individuals and for foreign-born individuals revealed differential predictors of age at death. For instance, opiate use disorder was the best predictor specifically for Spanish-born individuals, but psychotic disorder and tuberculosis were the best predictors for foreign-born individuals. These results suggest the usefulness of implementing specific prevention programs tailored to the features and needs of each subgroup.

Another important finding was that the mean age at death was nine years earlier for Spanish-born individuals in comparison with foreign-born individuals (49 years vs. 58 years, respectively). Our results are consistent with those of other studies that have revealed that non-immigrant background is a predictor of death among IEHs [37, 49]. Moreover, Spanish-born individuals showed worse overall health, e.g., higher prevalence of substance use disorders, multiple drug use, serious mental health disorders, and several chronic physical illnesses. Notably, health problems and mortality among foreign-born IEHs were also troublingly prevalent, but to a lesser extent compared to Spanish-born individuals.

A possible explanation for these results is the healthy immigrant effect, according to which foreign-born individuals are healthier and live longer than native-born individuals [19]. Likewise, the children of foreign-born parents are healthier and live longer than the children of locally born parents (although the outcomes vary depending on the mother’s country of origin) [21]. Our results suggest that this effect holds for the IEH population. As noted by Oliva-Arocas et al. [50], there may be protective cultural elements whereby the immigrant population would maintain more favorable mortality outcomes due to healthier habits related to diet or substance use. Specifically, it would be interesting to study why COPD affects foreigners less. Could it be due to lower tobacco consumption?

This hypothesis would fit with our data, as alcohol and drug use, obesity, hypertension, and respiratory diseases were substantially less prevalent among foreign-born individuals. However, the literature is not consistent on the existence of this healthy immigrant effect and both methodological aspects as well as certain variables may modulate the effect [19, 51]. In this line, a study in the Spanish general population found that mortality was lower in foreign-born individuals, compared with Spanish-born individuals [24]. However, nationality, country of origin, and length of stay in the host country influenced this effect. For instance, no significant differences in mortality were found when the length of stay in Spain was over 10 years.

Regardless of the healthy immigrant effect, the causes of death among foreign and native IEHs are different, as are the reasons why they reach a state of literal homelessness. These differences may have implications for the provision of services, highlighting the need to develop health and social care programs adapted to newcomers, in order to avoid more risk factors associated with homelessness and the concomitant deterioration of health [10]. Policies to protect the unemployed from poverty, increase employability and restore employment opportunities are needed to prevent the deterioration of the health of the population. The immigrant population must be protected by such policies, given that this group is especially vulnerable to the effects of economic and social crises [20].

Our results are subject to certain limitations. First, our sample was not designed to be representative of all IEHs in Spain, which could limit the generalizability of our results. Second, foreign-born IEHs may have migrated to other regions of Spain or other European countries, thus disappearing from Girona’s records. Third, this study only included data from people living literally homeless; unfortunately, it does not consider mortality among people who experience other forms of homelessness and housing exclusion. Lastly, we classified all foreigners in the same category, using country of birth as a segregation variable, without considering other variables related to the migration process, such as length of residence, administrative status, or belonging to an ethnic minority. Future research should take these elements into account in order to outline more precisely the variables of migration related to mortality and health.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the study suggests an alarming pattern of morbidity, mortality, and premature death among IEHs in Spain, especially among Spanish-born individuals. Our results show that most deaths were due to medical causes, especially cirrhosis, COPD, cardiovascular disease, and AIDS. Future studies should consider tobacco use in IEHs. While taken as a group, medical causes were the most prevalent, certain external causes of death (suicide, overdose) should be highlighted as they accounted for almost 40 per cent of overall deaths. Urgent efforts are needed to address the complex healthcare needs of IEHs and to reduce morbidity and mortality rates in this population.

Data Availability

Complete raw data are not publicly available to preserve participants’ anonymity in line with the obtained ethical approval for this study. However, further de-identifed data can be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Aldridge RW, Story A, Hwang SW, Nordentoft M, Luchenski SA, Hartwell G, et al. Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Lancet Publishing Group. 2018;391:241–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31869-X.

Baggett TP, Hwang SW, O’connell JJ, Porneala BC, Stringfellow EJ, Orav E, John, et al. Mortality among homeless adults in Boston shifts in causes of death over a 15-year period. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:189–95. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1604.

Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. The Lancet. 2014;384:1529–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6.

Riley ED, Cohen J, Shumway M. Overdose fatality and surveillance as a method for understanding mortality trends in homeless populations. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1264. trends in homeless populations. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173(13), 1264. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6838.

Slockers MT, Nusselder WJ, Rietjens J, van Beeck EF. Unnatural death: a major but largely preventable cause-of-death among homeless people? Eur J Public Health Oxford University Press. 2018;28:248–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky002.

Lee JY, Kwon N, Goo G, yeon, Cho S. il. Inadequate housing and pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. BioMed Central Ltd; 2022;22:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12879-6.

Hwang SW. Homelessness and health. Can Med Assoc J. 2001;164. https://www.cmaj.ca/content/164/2/229.full.

O’Connell JJ. Premature mortality in homeless populations: a review of the literature. editor. Nashville: National Health Care for the Homeless Council Inc; 2005.

Termorshuizen F, van Bergen APL, Smit RBJ, Smeets HM, van Ameijden EJC. Mortality and psychiatric disorders among public mental health care clients in Utrecht: a register-based cohort study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014;60:426–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764013491942.

Gil-Salmerón A, Guaita-Crespo E, Garcés-Ferrer J. Differentiating specific health needs of recent homeless immigrants: moving forward from an integrated approach to placate the “healthy immigrant effect. Int J Integr Care Ubiquity Press. 2019;19:621. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.s3621.

Gray D, Chau S, Huerta T, Frankish J. Urban-rural migration and health and quality of life in homeless people. J Soc Distress Homeless Informa UK Limited. 2011;20:75–93. https://doi.org/10.1179/105307811805365007.

Polillo A, Kerman N, Sylvestre J, Lee CM, Aubry T. The health of foreign-born homeless families living in the family shelter system. Int J Migr Health Soc Care Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. 2018;14:260–8. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMHSC-11-2017-0048.

Kaur H, Saad A, Magwood O, Alkhateeb Q, Mathew C, Khalaf G, et al. Understanding the health and housing experiences of refugees and other migrant populations experiencing homelessness or vulnerable housing: a systematic review using GRADE-CERQual. Can Med Association Open Access J. 2021;9:E681–92. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20200109.

Chiu S, Redelmeier DA, Tolomiczenko G, Kiss A, Hwang SW. The health of homeless immigrants. J Epidemiol Community Health (1978). 2009;63:943–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2009.088468.

Achotegui J. Emigrar hoy en situaciones extremas. El síndrome de Ulises Aloma. 2012;30:79–86.

Rivera B, Casal B, Currais L, Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. The healthy immigrant effect on mental health: determinants and implications for mental health policy in Spain. Administration and. Springer New York LLC; 2016;43:616–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0668-3.

Vang Z, Sigouin J, Flenon A, Gagnon A. The healthy immigrant effect in Canada: A systematic review. Population Change and Lifecourse Strategic Knowledge Cluster Discussion Paper Series/ Un Réseau stratégique de connaissances Changements de population et parcours de vie Document de travail. 2015;3. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/pclc/vol3/iss1/4.

Vang ZM, Sigouin J, Flenon A, Gagnon A. Are immigrants healthier than native-born Canadians? A systematic review of the healthy immigrant effect in Canada. Ethn Health Routledge. 2017;22:209–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2016.1246518.

Moullan Y, Jusot F. Why is the ‘healthy immigrant effect’’ different between european countries?’. Eur J Public Health Oxford Academic. 2014;24:80–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURPUB/CKU112.

Gotsens M, Malmusi D, Villarroel N, Vives-Cases C, Garcia-Subirats I, Hernando C, et al. Health inequality between immigrants and natives in Spain: the loss of the healthy immigrant effect in times of economic crisis. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25:923–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv126.

Stanek M, Requena M, del Rey A, García-Gómez J. Beyond the healthy immigrant paradox: decomposing differences in birthweight among immigrants in Spain. Global Health NLM (Medline). 2020;16:87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00612-0.

Calvo F, Carbonell X. Using WhatsApp for a homeless count. J Soc Distress Homeless Taylor & Francis. 2017;26:25–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2017.1286793.

Calvo F, Turró-Garriga O, Fàbregas C, Alfranca R, Calvet A, Salvans M, et al. Mortality risk factors for individuals experiencing homelessness in Catalonia (Spain): a 10-year retrospective cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041762.

Gimeno-Feliu LA, Calderón-Larrañaga A, DÍaz E, Laguna-Berna C, Poblador-Plou B, Coscollar-Santaliestra C, et al. The definition of immigrant status matters: impact of nationality, country of origin, and length of stay in host country on mortality estimates. BMC Public Health [Internet] BioMed Central. 2019;19:247. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6555-1.

Urquia ML, Gagnon AJ, Glossary. Migration and health. J Epidemiol Community Health (1978) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:467–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2010.109405.

World Health Organization. Suicide worldwide in 2019: global health estimates [Internet]. World Health Organization,Geneva. Geneve. ; 2021. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1350975/retrieve.

Ayano G, Tsegay L, Abraha M, Yohannes K. Suicidal ideation and attempt among homeless people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatr Q Psychiatr Q. 2019;90:829–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11126-019-09667-8/FIGURES/6.

Xiang J, Kaminga AC, Wu XY, Lai Z, Yang J, Lian Y, et al. Lifetime prevalence of suicidal attempt among homeless individuals in North America: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord Elsevier. 2021;287:341–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2021.03.052.

Calvo F, Carbonell X. Is Facebook use healthy for individuals experiencing homelessness? A scoping review on social networking and living in the streets. J Mental Health. 2019;28(5):505–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2019.1608927IF.

Calvo F, Carbonell X, Johnsen S. Information and Communication Technologies, eHealth and Homelessness: a bibliometric review. Cogent Psychol. 2019;6(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2019.1631583.

Gould MS, Lake AM, Galfalvy H, Kleinman M, Munfakh J, lou, Wright J et al. Follow-up with callers to the national suicide Prevention Lifeline: evaluation of callers’ perceptions of care. Suicide Life Threat Behav;48:75–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12339.

el País. El Hospital 12 de Octubre prueba una ‘app’ para prevenir el suicidio en pacientes psicóticos [[Hospital 12 de Octubre tests an “app” to prevent suicide in psychotic patients] [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Dec 28]. Available from: https://elpais.com/tecnologia/2019/09/25/actualidad/1569422310_097966.html.

Hashim A, Bremner S, Grove JI, Astbury S, Mengozzi M, O’Sullivan M, et al. Chronic liver disease in homeless individuals and performance of non-invasive liver fibrosis and injury markers: VALID study. Liver International. Volume 42. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2022. pp. 628–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103342.

Alfranca R, Salvans M, López C, Giralt C, Ramírez M, Calvo F. Hepatitis C in homeless people: reaching a hard-to-reach population. Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2021;113:529–32. https://doi.org/10.17235/reed.2021.7737/2020.

Statistics National Institute. Biometric features. Year 2020 [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Dec 28]. Available from: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736177004&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735573002.

Aldridge RW, Menezes D, Lewer D, Cornes M, Evans H, Blackburn RM, et al. Causes of death among homeless people: a population-based cross-sectional study of linked hospitalisation and mortality data in england. Wellcome Open Res. 2019;4. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15151.1.

Beijer U, Fugelstad A, Andreasson S, Ågren G. Mortality and causes of death among homeless women and men in Stockholm. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:121–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810393554.

Hwang SW. Mortality among residents of shelters, rooming houses, and hotels in Canada: 11 year follow-up study. BMJ. 2009;339:b4036. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b4036.

Garner L, Ratschen E. Tobacco smoking, associated risk behaviours, and experience with quitting: a qualitative study with homeless smokers addicted to drugs and alcohol. BMC Public Health BioMed Central. 2013;13:1–8.

Guardiola JM. Afectación pulmonar de las drogas inhaladas. Adicciones. 2006;18:161–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-951.

Nieva G, Ballbè M, Cano M, Carcolé B, Fernández T, Martínez À, et al. Intervenciones para dejar de fumar en los centros de atención a las drogodependencias de Cataluña: La adicción abandonada. Adicciones. 2021;34:227–34.

Baggett TP, Anderson R, Freyder PJ, Jarvie JA, Maryman K, Porter J, et al. Addressing tobacco use in homeless populations: a survey of health care professionals. J Health Care Poor Underserved Johns Hopkins University Press. 2012;23:1650–9. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2012.0162.

Baggett TP, Lebrun-Harris LA, Rigotti NA. Homelessness, cigarette smoking and desire to quit: results from a US national study. Addiction. Volume 108. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd;; 2013. pp. 2009–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12292.

Arnsten JH, Reid K, Bierer M, Rigotti N. Smoking behavior and interest in quitting among homeless smokers. Addict Behav Pergamon. 2004;29:1155–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.010.

Vijayaraghavan M, Elser H, Frazer K, Lindson N, Apollonio D. Interventions to reduce tobacco use in people experiencing homelessness. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Volume 12. John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2020. p. CD013413. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013413.pub2.

Huang B, de Vore D, Chirinos C, Wolf J, Low D, Willard-Grace R, et al. Strategies for recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for a clinical trial. BMC Med Res Methodol BioMed Central Ltd. 2019;19:1–10.

Al-Shakarchi NJ, Evans H, Luchenski SA, Story A, Banerjee A. Cardiovascular disease in homeless versus housed individuals: a systematic review of observational and interventional studies. Heart BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and British Cardiovascular Society. 2020;106:1483–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2020-316706.

Baggett TP, Liauw SS, Hwang SW. Cardiovascular disease and homelessness. J Am Coll Cardiol. Elsevier; 2018;71:2585–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.077.

Nielsen SF, Hjorthøj CR, Erlangsen A, Nordentoft M. Psychiatric disorders and mortality among people in homeless shelters in Denmark: a nationwide register-based cohort study. The Lancet. 2011;377:2205–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140.

Oliva-Arocas A, Pereyra-Zamora P, Copete JM, Vergara-Hernández C, Martínez-Beneito MA, Nolasco A. Socioeconomic inequalities in mortality among foreign-born and spanish-born in small areas in cities of the Mediterranean coast in Spain, 2009–2015. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4672. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH17134672.

Shor E, Roelfs D. A global meta-analysis of the immigrant mortality advantage. Int Migration Rev SAGE Publications Ltd. 2021;55:999–1028. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918321996347.

Acknowledgements

To people who have contributed to data collection: Mercè Salvans, Anna Julià, Carles Fàbregas, Sandra Castillejos, Anna Calvet, Cristina Giralt, Marissa Ramírez, Laura Masferrer. Susan Frekko provided feedback on the manuscript and translated it from the original Spanish.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FC, AG and RA were responsible for the conceptualisation and design of thestudy. FC and AP collected the data. FC, RA, XC and SF analysed and interpreted the data. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript; and all authors approved of the final manuscript submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institut d’Assistència Sanitària (CIEC-IAS), Catalan Institute of Health, with the code Estudi_homeless_2008 on December 12, 2014. On October 28, 2016 the same project was again supervised by the Research Ethics Committee CEI GIRONA with the name Evolució homeless de Girona: Seguiment longitudinal Cohort 2006/2016 (Code COHORT2006).

The ethical committee approved the study authorizing the analysis of health and mortality data of homeless people considering the exceptions for the signature of the informed consent by the patients. Informed consent was waived after approval by the ethics committee, taking into account the international and Spanish legal framework argued below:

Article 3. of Law 14/2007, on biomedical research, defines an observational study as one “conducted on individuals with respect to whom the treatment or intervention to which they might be subjected is not modified, nor are they prescribed any other guideline that could affect their personal integrity.“

Article 25 of the Declaration of Helsinki states: “For medical research involving identifiable human material or data, the physician should normally seek consent for collection, analysis, storage and reuse. There may be situations in which it will be impossible or impracticable to obtain consent for such research or could be a threat to its validity. In this situation, the research may only be conducted after consideration and approval by a research ethics committee.“

The Medical Research Council guidelines consider that exceptions to the need for informed consent for the use of personal data can be made when these five issues are adequately analyzed and justified:

Necessity (Are there valid alternatives for doing the study? Could anonymized information be used? Why is it not possible to seek authorization from patients?); Sensitivity (What and how sensitive is the information required by the research?); Significance (Will the research contribute to increasing knowledge in a substantive way?). Safeguards (Are security measures in place to prevent leaks and avoid harm to patients?); Independent review (Has a Research Ethics Committee evaluated the proposal and endorses the exception?).

The Spanish legal system, at the time the study approval was requested, established that access to the clinical history for research purposes (Law 41/2002) or the collection and processing of personal data (Law 15/1999) requires the express authorization of the interested party:

Article 6. 3 of the basic Law 41/2002 regulating patient autonomy and rights and obligations regarding clinical information and documentation, states, after the amendment to which it was subject by Law 33/2011 General Law on Public Health): “Access to the clinical history for judicial, epidemiological, public health, research or teaching purposes is governed by the provisions of Organic Law 15/1999, of 13 December, on the Protection of Personal Data, and Law 14/1986, of 25 April, General Health, and other regulations applicable in each case. Access to the clinical history for these purposes requires the preservation of the patient’s personal identification data, separate from those of a clinical-healthcare nature, so that, as a general rule, anonymity is assured, unless the patient himself has given his consent not to separate them”.

Article 7.3 of Organic Law 15/1999 on the Protection of Personal Data. As a general rule, it provided that “Personal data referring to racial origin, health and sex life may only be collected, processed and transferred when, for reasons of general interest, a law so provides or the affected party expressly consents.“

And Article 7.6 of this same Organic Law 15/1999 on Data Protection established the following as exceptions to the aforementioned article: “Notwithstanding the provisions of the preceding paragraphs, the personal data referred to in paragraphs 2 and 3 of this article may be processed when such processing is necessary for medical prevention or diagnosis, the provision of health care or medical treatment or the management of health services, provided that such data processing is carried out by a health professional subject to professional secrecy or by another person also subject to an equivalent obligation of secrecy.“

Article 11 of Organic Law 15/1999 on data protection stated “1. Personal data subject to processing may only be communicated to a third party for the fulfillment of purposes directly related to the legitimate functions of the transferor and transferee with the prior consent of the data subject. [3. Consent for the communication of personal data to a third party is null and void when the information provided to the data subject does not enable him/her to know the purpose for which the data whose communication is authorized or the type of activity of the recipient of the communication is intended. 4. Consent for the communication of personal data shall also be revocable. 5. The recipient of the communication of personal data undertakes, by the mere fact of communication, to comply with the provisions of this law. 6. If the communication is made after a disassociation procedure, the provisions of the previous paragraphs shall not apply.

In view of the fact that strict compliance with these Spanish legislative prescriptions would make many retrospective observational studies impossible or very costly, most authors in our country defend the possibility of making exceptions when certain requirements are met. Let us look at some of these proposals: “12. Only in exceptional circumstances may consent for the creation and/or use of records containing personal data for research purposes be dispensed with. The exception will have to be justified by the principal investigator for the specific case to be applied, and be discussed and approved by a Research Ethics Committee. When the information necessary to carry out the clinical or epidemiological research is to be obtained from the clinical history, the explicit consent of the subject will not be required if the researcher is part of the medical team attending him/her, although once the necessary information has been extracted and incorporated into the data collection notebook, it should be coded or anonymized appropriately to avoid a breach of confidentiality. In any case, the research and the procedure for obtaining the information must be approved by a Research Ethics Committee.“ And, “The collection of data from the clinical history for research requires the express consent of the patient. When the subject’s consent has not been obtained, it is recommended that access to the medical record be provided by a member of the health care team. Although this does not obviate the need for consent, given that the Law on Patient Autonomy guarantees access to the history for care and not for research, the fact that the healthcare professional has participated in obtaining the care data and is bound by professional secrecy offers an additional guarantee of confidentiality. It is recommended that the information should always be obtained in a dissociated form, to the extent possible for the development of the research.

In view of this, and in accordance with the recommendations of the Medical Research Council, the ethics committee considered that access to patients’ clinical records for clinical research purposes could be authorized without their consent, when the following requirements are met: (1) Necessity. It is not possible to seek patients’ authorization or to do so would involve unreasonable effort, (2) Sensitivity. The information to be collected is not exceptionally sensitive. (3) Importance. The results of the research will contribute significant knowledge to science.

Safeguards: (a) The collection of personal data from the clinical history will be carried out by healthcare professionals who are part of the team attending the patient. Health professionals, therefore, who collect the information or who have access to the patient’s clinical history. b) The collection of personal data from the clinical history will be collected in an anonymized form. In other words, once the clinical history has been collected, it will no longer be possible to find out in any way who it belongs to. The result will therefore not be a coded or dissociated personal data file, but a strictly epidemiological documentation.

In 2018, Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights came into force, which amended the previous law authorizing the present study. The new law, in its sixth transitory provision on reuse for health and biomedical research purposes of personal data collected prior to the entry into force of this organic law says: The reuse for health and biomedical research purposes of personal data lawfully collected prior to the entry into force of this organic law will be considered lawful and compatible when any of the following circumstances concur: (a) That such personal data are used for the specific purpose for which consent was given. (b) That, having obtained consent for a specific purpose, such data are used for purposes or areas of research related to the medical or research specialty in which the initial study was scientifically integrated.

Furthermore, the study also complies with Additional Provision 17.2 of Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on the Protection of Personal Data and guarantee of digital rights under Spanish law. As this was a retrospective observational study on mortality, it was not possible to access the participants to obtain informed consent. Given that the participants were homeless, many of whom came from other countries of origin, it was not possible to request informed consent from their relatives. Informed consent was obviated by Additional Provision 17.2.d LOPD-GDD on pseudo-anonymization of personal data. A personal data obtained from a process (pseudonymization), consists of the replacement of an attribute of a dataset by a pseudonym using a pseudonymization technique, so that its identification is not allowed without additional information (matching table). Additional Provision 17.2. d of the Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, on the Protection of Personal Data and guarantee of digital rights of the Spanish legal system establishes that pseudonymized data may be used for research purposes, without the need to obtain the consent of the data subjects, provided that there is a technical and functional separation between the team conducting the research and the one performing the pseudonymization, and that the data are only accessible within the research team that has signed a commitment of confidentiality and non-reidentification, and that technical measures have been adopted to prevent this re-identification and access by third parties. Thus, pseudonymization means “the processing of personal data in such a way that they can no longer be attributed to a data subject without the use of additional information, provided that this information is recorded separately and is subject to technical and organizational measures designed to ensure that the personal data are not attributed to an identified or identifiable natural person”.

Following the recommendations of the Research Ethics Committee CEI GIRONA, the researchers, who were themselves clinicians caring for people experiencing homelessness in the mental health and addictions and primary care services of the public health services, provided the database to an administrative team of the same institution. This administrative team proceeded to perform the pseudo-anonymization by reordering the database and attributing to each person a numerical code, complying with the criteria established in the Additional Provision 17.2.d of the Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, on Personal Data Protection and guarantee of digital rights of the Spanish legislation.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the same ethics committee, which is the reference ethics committee of the province of Girona public health services, annually renews the permission to continue analyzing the data of the cohort on which this study is based according to the Spanish legality reflected in this text. Therefore, the permission to proceed with research using this database is currently in force, in compliance with Spanish law. The renewal code of the permit is dated January 10, 2023 with the renewal code COHORT_2016.133.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Calvo, F., Guillén, A., Carbonell, X. et al. “Healthy immigrant effect” among individuals experiencing homelessness in Spain?: Foreign-born individuals had higher average age at death in 15-year retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 23, 1212 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16109-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16109-5