Abstract

Background

In recent decades, community-based interventions have been increasingly adopted in the field of health promotion and prevention. While their evaluation is relevant for health researchers, stakeholders and practitioners, conducting these evaluations is also challenging and there are no existing standards yet. The objective of this review is to scope peer-reviewed scientific publications on evaluation approaches used for community-based health promotion interventions. A special focus lies on children and adolescents’ prevention.

Methods

A scoping review of the scientific literature was conducted by searching three bibliographic databases (Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO). The search strategy encompassed search terms based on the PCC (Population, Concept, Context) scheme. Out of 6,402 identified hits, 44 articles were included in this review.

Results

Out of the 44 articles eligible for this scoping review, the majority reported on studies conducted in the USA (n = 28), the UK (n = 6), Canada (n = 4) and Australia (n = 2). One study each was reported from Belgium, Denmark, Germany and Scotland, respectively. The included studies described interventions that mostly focused on obesity prevention, healthy nutrition promotion or well-being of children and adolescents. Nineteen articles included more than one evaluation design (e.g., process or outcome evaluation). Therefore, in total we identified 65 study designs within the scope of this review. Outcome evaluations often included randomized controlled trials (RCTs; 34.2%) or specific forms of RCTs (cluster RCTs; 9.8%) or quasi-experimental designs (26.8%). Process evaluation was mainly used in cohort (54.2%) and cross-sectional studies (33.3%). Only few articles used established evaluation frameworks or research concepts as a basis for the evaluation.

Conclusion

Few studies presented comprehensive evaluation study protocols or approaches with different study designs in one paper. Therefore, holistic evaluation approaches were difficult to retrieve from the classical publication formats. However, these publications would be helpful to further guide public health evaluators, contribute to methodological discussions and to inform stakeholders in research and practice to make decisions based on evaluation results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The field of health promotion and prevention has increasingly adopted community-based approaches over the past decades [1]. In addition to a wide range of meanings, the term ‘community-based’ can be defined as a setting, which is primarily geographical and is considered to be the place where interventions are carried out [2].

In the context of health promotion and prevention strategies, communities are highly relevant for planning and conducting interventions. Community-based approaches can enable access to target groups that are difficult to reach, such as people experiencing social disadvantages and people with existing health problems, without stigmatizing them in their daily lives [3].

Children and adolescents are an important target group in primary health promotion and prevention. If they come from families experiencing social disadvantages, they are not only more often exposed to health risks, but also less likely to benefit from health-related resources [4]. As communities are in position to change and adapt many health-related living conditions in different settings, they can play a key role in reaching this target group [4]. Therefore, health promotion measures can contribute to the reduction of socially determined inequalities in children's health opportunities and provide them with good development and participation perspectives regardless of their social status [4].

The latest approaches of community-based health promotion are determined by multiple components or complex interventions [5]. According to the Medical Research Council (MRC), an intervention is considered complex either because of the nature of the intervention itself or the “complex” way in which the intervention generates outcomes [6].

Evaluating complex interventions requires an appropriate set of methods to capture their different dimensions of effects, and to assess their impact and possible unintended consequences at the individual and societal levels. The key functions in evaluating complex interventions are assessing effectiveness, understanding change processes and implementation barriers and facilitators, and assessing cost-effectiveness [7]. Methodologically, we differentiate between process and outcome evaluations. Outcome evaluations on their own are often not sufficient or adequate to describe change in a system, but the process itself needs to be evaluated, such as the assessment of implementation fidelity and quality [7].

This understanding is important to implement interventions in a sustainable way, to describe processes such as empowerment and/or to justify policy and funding decisions. In addition, it allows future decisions and interventions to be further developed and improved. Achieving this goal requires comprehensive evaluation strategies and concepts with an elaborate set of combined methods, such as qualitative, quantitative and/or mixed methods within process and/or outcome evaluations [8, 9]. Theoretical evaluation frameworks, such as the RE-AIM framework [10] and others, can be used for planning and realizing evaluation approaches.

Although evaluation of public health interventions and more specifically community-based interventions is increasingly recognized as an important component of project conceptualization, implementation and management, published high quality methodology remains a major challenge [11].

To date, there are a range of strategies and concepts using a variety of qualitative and quantitative methods applied in different study designs to evaluate community-based interventions. To provide an overview and inform on current (good) practices, this scoping review aims at reporting on the strategies, concepts and methods used in studies evaluating community-based interventions focusing on health promotion and prevention in children and adolescents living in high-income countries.

Methods

This scoping review was based on the framework by Arksey and O'Malley [12], which includes the following steps: identification of the research question and relevant studies, study selection, charting data, and collating, summarizing, and reporting results. The PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [13] and a pre-registered protocol were used as a guide in preparing the scoping review. The protocol was published in advance in the Open Science Framework and is accessible at the following link: https://osf.io/7vmah.

Search strategy

To specify the search strategy, the categories of the PCC scheme (Population, Concept, Context) [14] were used and determinants were created based on the research question (Table 1).

Three bibliographic databases were searched: Medline, EMBASE and PsycINFO. Keywords, truncations as well as limits to title and abstract fields were used for the database searches. The search strategy was adapted to the respective subcategories for each database, whereas the search terms remained identical. The following search strategy was used for the Medline and EMBASE databases: (child.tw. OR children.tw. OR teenager*.tw. OR youth.tw. OR adolescent*.tw.) AND (evaluat*.tw. OR monitor*tw.) AND (prevention.tw. OR health promotion/ OR health education/) AND (intervention.tw. OR program.tw. OR programme.tw. OR activit*.tw.) AND (communit*.tw. OR municipal*.tw. OR local.tw. OR neighbo?rhood.tw. OR rural.tw. OR urban.tw. OR district.tw.).

Database searches were conducted on April 8th, 2022. Only studies in English or German language were included. Due to the increase and further development of interventions in the community setting, the search was limited to publications from the last ten years (January 1st, 2012- until time of search).

The PCC framework [14] was used to establish the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). Study design has been noted as an additional category.

Studies in which the intervention also involved parents or other caregivers were taken into account, as long as the outcome primarily targeted children and adolescents.

We included only studies following a general population-based approach, i.e., offering interventions for the general population, not for specific risk populations [17]. Furthermore, we included only interventions in community settings and excluded school or hospital settings [18]. Institutional settings were only comprised if they were mentioned in addition to other settings and the intervention was not actively carried out there (e.g., recruitment through flyers posted at schools). Due to contact restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic almost all community-based interventions were subject to profound adaptations (e.g., transition to digital offers). Since we wanted to provide a general overview of evaluation concepts not only restricted to pandemic circumstances, all COVID-19 related studies were excluded. Low- and middle-income countries were excluded because they face different circumstances, special target groups and different networking opportunities compared to high-income countries. Furthermore, reviews and meta-analyses were excluded, but their reference lists were checked to identify additional studies using the snowballing approach [19].

Study selection

Search results were exported to the citation management software Endnote, where duplicates were removed. The study selection process was divided into two phases: (1) Title and abstract screening and (2) full text screening. The title and abstract screening was conducted by all authors using Rayyan [20], a web-based application that supports the initial title and screening process allowing the online collaboration of several researchers. To improve consistency between authors, all authors screened titles and abstracts of the same 100 publications, discussed the results and jointly adapted the guidance for the title and abstract screening, before starting the titles and abstract screening of all references.

For the full text screening, the included studies were integrated in an Excel spreadsheet available for all authors and validated by discussions with all authors. The same authors as in the title and abstract screening were involved in the full text screening process. In title and abstract as well as full text screening, 20% of the publications were reviewed independently by a second author. Discrepancies were discussed in the team and a decision was made collectively. In the title/abstract and the full text screening, publications were selected based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data extraction

Included studies were extracted using a customized spreadsheet. The data extraction was divided into two parts. The first part contained the general information such as first author, year of publication, country, population characteristics, setting, components, description of the intervention, frequency and duration of the intervention, presence of a comparison group, the objective(s) of the intervention and the type of article.

The second part comprised specific information focusing on the evaluation strategy, i.e., was the term process evaluation used (yes/no), was the term outcome evaluation used (yes/no), study type (observational/interventional), study design (randomized controlled trial (RCT)/cluster RCT/quasi-experimental/cross-sectional study/cohort study/case study) and the methods used (qualitative/quantitative/mixed methods). Furthermore, we extracted whether an evaluation framework, guidance or theoretical research approach was used.

We categorized studies as interventional if they were either experimental and/or quasi-experimental. If the study design was not explicitly mentioned, the categorization was done by the authors based on the methods section of the study.

The research team developed the data extraction sheet collaboratively. The first author (BB) independently extracted data from all included studies. Twenty percent were checked and extracted by a second author and discussed in the team to assess applicability and consistency of data extraction. Disagreements were discussed in the team and decisions were made collectively.

Data synthesis

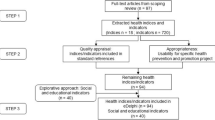

The selection process was visualized by a PRISMA-ScR flowchart showing the results of the screening steps (Fig. 1). The results of the data extraction were presented in tables and as a narrative summary.

Results

A total of 6,402 articles were identified from searching the three bibliographic databases after the removal of duplicates, 3,959 publications remained for the title and abstract screening. A total of 130 reviews were identified in the literature search of which 20 were considered as relevant for our research question. From these reviews, 28 additional studies were eligible for the full text screening [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

A total of 350 articles were included for full text screening and assessed for eligibility. Here, 44 studies met our inclusion criteria, while 306 were excluded. The most prevalent exclusion criterion was the wrong setting (n = 171). This criterion was applied, for instance, if the whole or a part of the intervention took place in an institutional setting such as schools. Another exclusion criterion was “wrong population” (n = 76). Examples for this criterion to be applied was: children were not involved in the intervention, although the outcome might have targeted them. Other exclusion criteria were wrong study type (e.g., non-empirical studies, n = 6), wrong intervention (n = 8); lack of health-related outcome; no full text available (conference abstracts (n = 36)), and no accessibility to the full article (n = 9). If there was more than one reason for exclusion, the final reason was chosen according to the following hierarchy: 1) wrong study type, 2) wrong setting, 3) wrong population and 4) wrong intervention.

Characteristics of included studies

Table 3 provides an overview of included studies. Included articles were published between 2012 and 2022, and addressed either primary studies with research findings (n = 38) or published research protocols (n = 6). The studies were mainly conducted in the USA (n = 28; 63.6%), followed by the UK (n = 6; 13.6%), Canada (n = 4; 9.1%), Australia (n = 2; 4.6%), Belgium (n = 1; 2.2%), Denmark (n = 1; 2.2%), Germany (n = 1; 2.2%) and Scotland (n = 1; 2.2%).

Among the children and adolescents examined in the included studies, age ranged from 0 to 19 years, and the population often received the intervention as families or parent-child dyads.

In most cases, interventions mainly aimed at: obesity prevention (n = 23; 52.3%), healthy nutrition promotion (n = 15; 34.1%), well-being (n = 9; 20.5%), problematic behavior prevention (including antisocial behavior, substance use, violence, delinquency; n = 7; 15.9%) or sexual violence and/or adolescent relationship abuse prevention (n = 4; 9.1%). Five interventions were reported in more than one of the included studies. Thus, 36 different interventions were represented in the 44 included studies. The studies used different study designs such as observational study designs (n = 17) and interventional study designs (n = 27).

Strategies and methods of evaluation

Of the 44 articles included, nearly half of them aimed at evaluating outcomes only (n = 20; 45.5%) [42, 47, 48, 50, 52, 55, 58, 61, 63, 64, 66,67,68,69, 71, 77,78,79, 82, 83], whereas 18 described outcome and process evaluation (40.9%) [41, 43,44,45,46, 49, 51, 53, 54, 57, 59, 62, 70, 72,73,74, 81, 84], and 6 focused on process evaluation solely (n = 6; 13.6%) (56, 60, 65,75, 76, 80). However, only a few studies explicitly used the terms ‘process evaluation’ (n = 14) and/or ‘outcome evaluation’ (n = 4) to describe their evaluation strategies.

A total of 19 studies presented more than one method used for evaluation (e.g., cross-sectional study and RCT applied within one study). Therefore, this review identified 65 study designs within different evaluation classifications (Table 4).

Studies reporting on outcome evaluations often applied RCTs (34.2%), specific forms of RCTs (such as cluster RCTs; 9.8%) or quasi-experimental designs (26.8%). Other study designs for outcome evaluation strategies were observational study designs, such as cohort studies (17.1%) or cross-sectional studies (12.2%; almost half of them used a repeated cross-sectional design). Process evaluation strategies were described in 48.8% (n = 20) of the included studies (53.6% (n = 15) within interventional designs and 38.5% (n = 5) within observational designs). Process evaluation used mainly cohort (54.2%) and cross-sectional study designs (33.3%); one out of 8 used a repeated cross-sectional study design. Two quasi-experimental and one case study were included.

In terms of methods used, in 25 publications including 33 different study designs quantitative methods were reported (n [41, 46,47,48,49,50, 54, 55, 58, 61, 64, 66,67,68,69, 71, 75,76,77,78,79, 81,82,83,84], 16 publications reported on 27 mixed method designs (n) [42,43,44,45, 51,52,53, 56, 57, 60, 62, 63, 70, 73, 74, 80] and 3 publications reported on 5 qualitative methods based designs [59, 65, 72] (Table 5).

Reference to frameworks, theories or guidance of included studies

Few studies referred to frameworks or guidelines that provide a basis for evaluation. Bottorff et al. [44, 45] and Jung et al. [62] referred to the RE-AIM framework (RE-AIM = reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance), which is an evidence-based framework developed for assessing the real-world applicability and effectiveness of health-related interventions in community settings [10, 44].

The RE-AIM framework was used for outcome and process evaluation and focused on the five established dimensions: reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance. Both studies referring to RE-AIM were examining the same intervention from different perspectives. They each conducted an observational study – i.e. cross-sectional and cohort study.

Other authors such as Gillespie et al. referred to the MRC guidance [53]. They presented both outcome and process evaluation in their study protocol for a RCT. They planned to use a logic model with three phases: participatory methods (phase 1), recruitment, consent, randomization (phase 2), and intervention trial (phase 3). Each phase included the following dimensions: activities, reach, short-term outcomes, intermediate outcomes and long-term outcomes. They designed their process analysis according to the MRC guideline for process evaluation [85]. Within phase 1 and 2, data will be evaluated in terms of participatory, co-productive approach and possible adjustments to the original design or methods. In phase 3, components of implementation will be considered such as context, feasibility and acceptability.

Several of the identified studies focused on the same intervention approach: four studies focused on the Communities that Care (CTC) approach – a scientific approach to address problem behaviors in children and adolescents on a community level. The CTC approach consists of 5 phases: assess community readiness, get organized at community level, develop a community profile, select and implement suitable evidence-based programs. For each phase, there is a detailed task description and a tool for self-reporting the benchmarks achieved.

To evaluate CTC approaches, Rhew et al. [71], Röding et al. [74] and Salazar et al. [75, 76] used quasi-experimental designs with other communities as comparison groups. The last two groups of authors also integrated a logic model.

The Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approach was applied in four of the included studies. CBPR is defined as a collaborative effort and equal partnering of all stages of the research process between researchers and community members and organizations to meet the needs of the community [86]. Berge et al. [43] used a quasi-experimental design for the implementation of the intervention and a cross-sectional design for the process evaluation. The core principles of the CBPR approach were described and the authors used the theoretical Citizen Health Care Model, a CBPR approach, to guide the study design as well as hypothesis development and analyses. Grier et al. [56] and McIntosh et al. [65] used observational designs for their process evaluation and showed a positive response from community members through the collaborative approach. White et al. [84] conducted interventional studies and demonstrated both process and outcome evaluation, using the CBPR approach as the structure of their study.

Discussion

In this review, we scoped the existing literature on evaluation strategies, study designs, concepts and methods used for community-based health promotion and prevention interventions targeting children and adolescents. Overall, we included 44 studies based on our predefined search criteria and identified a total of 65 evaluation designs used in these studies. We identified different evaluation strategies and methods that have been used in this research field. Our main results were i) a content related focus of studies reporting on the evaluation of intervention targeting obesity and nutrition, ii) a methodological imbalance and focus on outcome evaluation strategies with RCTs and/or quasi-experimental designs to the disadvantage of process evaluation strategies and qualitative methods in the included studies, and iii) a lack of application of or referral to consistent standards, guidance or methods for the design of evaluation strategies.

-

i)

Aim of interventions

The majority of the studies focused, among others, on the prevention of obesity and were also often linked to the promotion of healthy nutrition. This may be due to the fact that obesity, defined as “abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health” [87] by the World Health Organization (WHO) is considered one of the most prevalent health issues facing children and adolescents worldwide [87]. Although there is evidence that obesity rates are stagnating or decreasing in many high-income countries [88], it is still a relevant issue as the numbers remain high [89].

Community-based interventions, combined with population-wide interventions (e.g., social marketing campaigns), and structural modifications (e.g., establishment of networks and partnerships), are recommended by the WHO as an effective and long-lasting way to prevent childhood obesity [90]. As our review focuses on the community setting, this may also reflect a reason for the large proportion of these health prevention interventions in the included studies.

Other areas that have emerged in our research were the prevention of problem behavior and the prevention of sexual violence and/or relationship abuse among adolescents. Problematic behavior included issues such as antisocial behavior, substance use, violence or delinquency. The relevance of these fields could be explained by the fact that, in general, adolescence is a period with an increased susceptibility to risky behavior [49]. At the same time, this phase in life can also be characterized by the development of positive values and skills [49].

-

ii)

Evaluation strategies: Outcome and process evaluation

A range of study designs are available and each design is differently suited to answer different research questions. Our research reveals two areas in which different study designs were preferred for evaluation: outcome evaluation and process evaluation. Based on our results, it seems like the focus is still mainly on outcome evaluation, as most of the publications referred to outcome evaluations and only half of them integrated process evaluation strategies. A preponderance of outcome evaluations may be due to the current general dominance of this methodology in science, as it is often solely about effectiveness and effects are often measured in numbers. However, process evaluation strategies are equally relevant as they help to understand why a program has been successful or not. Applying process evaluation strategies is also of utmost importance to guide and support the process of implementing and adapt interventions and finally to facilitate the consolidation and sustainability of interventions in the community.

Furthermore, the terms 'process evaluation' and 'outcome evaluation' were hardly used in studies included in our review (the former, however, more often). Nevertheless, only few studies could be included that dealt exclusively with process evaluation. This may be due to our own methodology and is referred to in the ‘Strengths and Limitations’ section. Studies dealing with outcome evaluations were also integrating process evaluation or the wording quite rare.

It is questionable whether this is caused by the fact that studies dealing with outcome evaluations have not conducted any process evaluation strategies at all. One alternative explanation could be a publication bias favoring quantitative studies over qualitative or the fact that health care researchers are not yet familiar with the concepts of process and outcome evaluation. On the other hand, using the term ‘outcome evaluation’ does not seem to be common practice in the research field of studying the effectiveness of an intervention, or the researchers involved may not always be aware that they are conducting an outcome evaluation. This reflects the need to disseminate these evaluation strategies and methods more widely among scientists to obtain comprehensive evaluations using both strategies and applying different quantitative and qualitative methods in the future.

In the context of outcome evaluations, the focus was primarily on interventional studies such as RCTs (including adaptions such as cluster RCTs) and quasi-experimental studies, respectively. RCTs are known for their ability to verify the cause-effect relationship between an intervention and an outcome, and are therefore the gold standard for evaluating effectiveness [91]. Despite their high level of evidence, they may also often not be feasible or adequate in the area or setting of community-based health promotion interventions. RCTs can be particularly limited when the context of implementation essentially affects the outcome. The conditions in an experiment may differ from those in real life and the results may not apply in a non-experimental setting [39, 92, 93]. In order to improve the impact of complex intervention research, standard designs such as RCTs need to be further developed and adapted to suit complex intervention contexts according to the MRC guidance [7, 93]. In our review only four studies used an adaptation of this study design, i.e. cluster RCTs.

Especially in community settings, such study designs are feasible and valuable for conducting interventions at group levels and/or avoiding potential contamination between groups [94]. Robinson et al. [73] conducted their study in two community-based settings. They used one RCT and one cluster RCT and reported that in both trials, no impact on the outcome was demonstrated by the intervention. The reason for the different study designs was neither addressed nor discussed in the study. However, this would have been an important and interesting point of discussion. In practice, it may not be possible to randomly distribute the intervention due to practical or ethical reasons. Especially in the context of a community, it may not be feasible for only half of the people or sites to receive an intervention. This could lead to spillover effects, underestimating the overall benefit of the intervention for the target population [95].

Due to a growing interest in comparative effectiveness studies and the raising relevance of external validity, quasi-experimental and non-experimental studies have received increased attention in the field of public health. Natural and quasi-experimental approaches provide the opportunity to access changes in a system that would be difficult to influence through experimental designs [96]. Especially in community-based interventions, environmental changes are often added as part of the intervention as seen in this review. Due to the combination of characteristics of experimental and non-experimental designs, quasi-experimental studies can cover such interventions and their evaluation. Quasi-experiments usually use data on other entire population groups [97]. In the study of Bell et al. included in this review, 20 matched communities were used as control groups for the outcome evaluation [42]. Data is usually collected using routine data systems such as clinical records or census data [97]. However, a common criticism of quasi-experimental studies is that the processes leading to variations are beyond the control of the studies [98]. Therefore, it impossible to determine whether confounding has been successfully prevented [98].

Quantitative methods were used in 11 of 14 RCTs and 3 of 4 cluster RCTs within the studies reported here. As these study designs can specifically demonstrate effectiveness and causal associations, the choice of methodology is appropriate for outcome evaluations. However, a purely quantitative approach within a RCT without additional components such as process analysis is hardly suitable for the evaluation of complex interventions according to MRC guidance [93]. Quite often, it will be necessary to answer those questions that go beyond effectiveness. Qualitative or mixed methods are more appropriate for this purpose [93] as qualitative research may give insights into subjective views and perceptions of individuals and stakeholders. In process evaluation studies in this review, we were able to identify mainly observational designs such as cross-sectional or cohort studies. Although guidelines exist and process evaluations are carried out in principle [99], the methodological variety available for process evaluation strategies do not seem to be exploited to its full potential to date. We hypothesize that there is room for development here, since qualitative methods are suitable to elaborate important indications why an intervention is (or is not) working and how it could be improved. In addition, the iterative nature of data collection and interpretation in qualitative methods support participatory adaptation of the intervention and knowledge translation into the field of interest during implementation. Or vice versa, if qualitative methods are not incorporated into evaluation strategies, important findings may be missed and possible new hypotheses, views and developments may not be recognized and noted.

-

iii)

Concepts and guidelines

Only a few studies were found in this review that explicitly referred to guidelines, frameworks or similar concepts for evaluation [44, 45, 62]. Among those, RE-AIM offers an efficient framework and thus provides a systematic structure for both planning and evaluating health-related interventions [85]. Jung et al. [62] provided a precise overview of their steps and each of the five dimensions of the framework were evaluated individually using a mixed-methods study design. It was also described that mainly quantitative methods were used to examine outcomes. For the process evaluation, on the other hand, more qualitative methods should be used to get rich and meaningful data. This kind of data could be used to guide the conceptualization and implementation of complex interventions. Bottorff et al. [45] described the RE-AIM framework as another feasible option to collect information to guide planning for future scale-up. In this sense, it offers a robust concept to guide evaluation approaches. Limitations of the evaluation remain, however, due to the difficulty of balancing a scientifically relevant evaluation with the needs of the study participants through appropriate assessment instruments [45].

Other pragmatic guidance is offered by the MRC framework, the CTC approach and principles of CBPR. Gillespie et al. [53], for instance, included both a logic model and the MRC's guidance for process evaluations in their evaluation concept. The MRC recommends a framework based on the themes of implementation, mechanisms and context. The guidance provides an overview of key recommendations regarding planning, design and implementation, analysis and reporting, and suggests, among other things, the use of a logic model to clarify causal assumptions [99].

Another approach used in this review was the CTC approach [71, 74,75,76]. This framework was originally developed in the US to guide community coalitions in planning and implementing community-based health promotion interventions targeting children and adolescents [100]. This is primarily an implementation plan, but also provides information on quality assessment and further development. CTC offers evaluation tools and supports the implementation process [74]. CTC is more common in the USA but is increasingly being used in other countries. Although evidence and tools for the process of CTC are provided, precise concepts for outcome evaluation seem to be lacking here as well.

Principles of CBPR were also used in four studies [43, 56, 65, 84]. These focused mainly on process evaluation, which reflects the relevance of this evaluation approach, as it is particularly important to ascertain whether the intervention is accepted by all participants in a collaborative environment. The CBPR approach provides structure for developing and implementing interventions, but also includes approaches for evaluating processes and outcomes. CBPR projects are characterized by several core principles that are designed to enable and strengthen the collaborative approach, and focus on action and participation of all stakeholders [101]. Due to individual research questions and contexts of each partnership, it is impossible to prescribe a design to be used; rather, each must determine for itself what is most appropriate [101]. The principles serve as a guideline and support to develop own structures. Through the collaborative process, data can be collected that accurately reflects the real-world experiences of the members [102]. Berge et al. [43] demonstrated that using the CBPR framework, researchers and community members collaboratively developed an intervention, and results showed high participant satisfaction in addition to high feasibility. Although there are also concrete logical models of the CBPR approach that give clear structures about contexts, group dynamics, interventions and outcomes [103], these were not integrated in the studies of this review.

Strengths and limitations

As with any project, the chosen approach, design and methodology has several limitations as well as strengths. One limitation was that we potentially missed out some studies or study designs by applying the defined search strategy which 1) was limited to the last 10 years, 2) only included sources published in the English or German language, 3) used specific search terms narrowed by the PCC scheme, and 4) was only conducted in three databases. The latter aspect could have led to the fact that studies using process evaluation strategies may have been underrepresented, as the selected databases may be very medically and quantitatively loaded. Another limitation of the work was the exclusion of interventions conducted in institutional setting such as schools. This setting plays an important role in health promotion for children and adolescents. It particularly offers practical opportunities for the implementation of comprehensive strategies, but was not explored due to the institutional approach with different characteristics than a purely community-based approach. Therefore, our understanding of community based approaches was narrow by nature. A methodological challenge, especially during the screening process, was the heterogeneity and equivocality of the terminology used for community-based health promotion and prevention projects. For future projects, a broader approach and scope of the review, including additional keywords and databases for the search strategy, could be considered. Additionally, databases that focus on other subject areas such as education sciences or social sciences could provide more results with regard to studies using process evaluation strategies.

A key strength of the scoping review was the sound methodology based on the framework recommended by Arksey and O'Malley and the PRISMA-ScR checklist. Furthermore, the collaborative approach, as well as the 20% double screening in each of the screening and data extraction phases as well as regular team discussions in all stages of the project, ensured consistency, feasibility and thus a high level of quality. The review provides an overview of selected study designs and methodologies for future research. While there is no clear recommended approach, researchers can use our review to guide future interventions and get suggestions for evaluation concepts and strategies.

Conclusion

In our scoping review, we identified important trends in the field of health prevention and promotion evaluations of children and adolescents in high-income countries. Although a variety of different methods and approaches exist, the choice of methods to evaluate community-based interventions depends on various factors. Guidance to inform approaches can be drawn from RE-AIM, the CTC and CBPR concepts. The widely used and recently updated MRC framework indicates that evaluation is moving beyond questions of effectiveness and is therefore leading to a change in research priority, which includes the importance of process evaluation and qualitative methods [93]. Increasing attention will be paid to whether and how the acceptability, feasibility and transferability of an intervention can be obtained in different settings or contexts [93]. As evaluation concepts and strategies are complex with a wide range of contexts and methods to consider, it would be helpful to expand publication strategies on the evaluation of complex interventions to further guide public health experts and scientists, to contribute to methodological discussions and to make informed and evidence-based decisions based on evaluation results.

Availability of data and materials

The protocol is published in OSF. Additional information is available upon request to the corresponding author (CJS).

Abbreviations

- CBPR:

-

Community-based participatory research approach

- CTC:

-

Communities That Care

- MRC:

-

Medical Research Council

- PCC:

-

Population, Concept, Context

- PRISMA‐ScR:

-

PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Trojan A, Süß W, Lorentz C, Nickel S, Wolf K. Quartiersbezogene Gesundheitsförderung: Umsetzung und Evaluation eines integrierten lebensweltbezogenen Handlungsansatzes. Weinheim Basel: Beltz Verlag; 2013.

McLeroy KR, Norton BL, Kegler MC, Burdine JN, Sumaya CV. Community-based interventions. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):529–33.

GKV-Spitzenverband. Leitfaden Prävention. Handlungsfelder und Kriterien nach § 20 Abs. 2 SGB V 2021 [Available from: https://www.gkv-spitzenverband.de/media/dokumente/krankenversicherung_1/praevention__selbsthilfe__beratung/praevention/praevention_leitfaden/2021_Leitfaden_Pravention_komplett_P210177_barrierefrei3.pdf.

Ehlen S, Rehaag R. Analysis of comprehensive community-based health promotion approaches for children : Health prospects in disadvantaged neighborhoods in Germany’s Ruhr area. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2018;61(10):1260–9.

Nickel S, von dem Knesebeck O. Effectiveness of community-based health promotion interventions in urban areas: a systematic review. J Community Health. 2020;45(2):419–34.

Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, et al. Framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions: gap analysis, workshop and consultation-informed update. Health Technol Assess. 2021;25(57):1–132.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337: a1655.

Lobo R, Petrich M, Burns SK. Supporting health promotion practitioners to undertake evaluation for program development. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1315.

Public Health England. A Guide to Community-Centred Apporaches to Health and Well-being Full Report. London: Public Health England; 2015.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–7.

De Bock F, Spura A. Evidenzbasierung: Theoriebildung und praktische Umsetzung in Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz. 2021;64(5):511–3.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien K, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, McInerney P, Soares CB, Khalil H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers' manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews 2015 [Available from: https://nursing.lsuhsc.edu/JBI/docs/ReviewersManuals/Scoping-.pdf.

World Health Organization. Recognizing adolescence 2014 [Available from: https://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/section2/page1/recognizing-adolescence.html.

World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups 2022 [Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

Platt JM, Keyes KM, Galea S. Efficiency or equity? Simulating the impact of high-risk and population intervention strategies for the prevention of disease. SSM Popul Health. 2016;3:1–8.

Zaglio A. The Jakarta Declaration on Leading Health Promotion into the 21st Century. Ann Ig. 1998;10(1):3–7.

Wohlin C. Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. In: Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering. London: Association for Computing Machinery; 2014. p. 38.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210.

Angawi K, Gaissi A. Systematic Review of Setting-Based Interventions for Preventing Childhood Obesity. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:4477534.

Bahner J, Stenqvist K. Motivational Interviewing as Evidence-Based Practice? An Example from Sexual Risk Reduction Interventions Targeting Adolescents and Young Adults. Sexual Res Soc Policy. 2020;17(2):301–13.

Brown T, Moore TH, Hooper L, Gao Y, Zayegh A, Ijaz S, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7(7):Cd001871.

Busiol D, Shek DTL, Lee TY. A review of adolescent prevention and positive youth development programs in non-English speaking European countries. Int J Disabil Human Dev. 2016;15(3):321–30.

Curran T, Wexler L. School-based positive youth development: a systematic review of the literature. J Sch Health. 2017;87(1):71–80.

Dickson K, Melendez-Torres GJ, Fletcher A, Hinds K, Thomas J, Stansfield C, et al. How do contextual factors influence implementation and receipt of positive youth development programs addressing substance use and violence? A qualitative meta-synthesis of process evaluations. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(4):1110–21.

Downing KL, Hnatiuk JA, Hinkley T, Salmon J, Hesketh KD. Interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour in 0-5-year-olds: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(5):314–21.

Dunne T, Bishop L, Avery S, Darcy S. A review of effective youth engagement strategies for mental health and substance use interventions. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(5):487–512.

Eadeh HM, Breaux R, Nikolas MA. A meta-analytic review of emotion regulation focused psychosocial interventions for adolescents. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2021;24(4):684–706.

Fanshawe TR, Halliwell W, Lindson N, Aveyard P, Livingstone-Banks J, Hartmann-Boyce J. Tobacco cessation interventions for young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11(11):Cd003289.

Flynn AC, Suleiman F, Windsor-Aubrey H, Wolfe I, O’Keeffe M, Poston L, et al. Preventing and treating childhood overweight and obesity in children up to 5 years old: A systematic review by intervention setting. Matern Child Nutr. 2022;18(3): e13354.

Hillier-Brown FC, Bambra CL, Cairns JM, Kasim A, Moore HJ, Summerbell CD. A systematic review of the effectiveness of individual, community and societal level interventions at reducing socioeconomic inequalities in obesity amongst children. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:834.

Hirsch KE, Blomquist KK. Community-Based Prevention Programs for Disordered Eating and Obesity: Updates and Current Limitations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9(2):81–97.

Karacabeyli D, Allender S, Pinkney S, Amed S. Evaluation of complex community-based childhood obesity prevention interventions. Obes Rev. 2018;19(8):1080–92.

Martin A, Booth JN, Laird Y, Sproule J, Reilly JJ, Saunders DH. Physical activity, diet and other behavioural interventions for improving cognition and school achievement in children and adolescents with obesity or overweight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1(1):Cd009728.

Sandhu R, Mbuagbaw L, Tarride JE, De Rubeis V, Carsley S, Anderson LN. Methodological approaches to the design and analysis of nonrandomized intervention studies for the prevention of child and adolescent obesity. Can J Public Health. 2020;111(3):358–70.

Specchia ML, Barbara A, Campanella P, Parente P, Mogini V, Ricciardi W, et al. Highly-integrated programs for the prevention of obesity and overweight in children and adolescents: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2018;54(4):332–9.

Tremblay M, Baydala L, Khan M, Currie C, Morley K, Burkholder C, et al. Primary Substance Use Prevention Programs for Children and Youth: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2020;146(3):e20192747.

Wang S, Moss JR, Hiller JE. Applicability and transferability of interventions in evidence-based public health. Health Promot Int. 2006;21(1):76–83.

Wilcox HC, Wyman PA. Suicide Prevention Strategies for Improving Population Health. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2016;25(2):219–33.

Abebe KZ, Jones KA, Culyba AJ, Feliz NB, Anderson H, Torres I, et al. Engendering healthy masculinities to prevent sexual violence: Rationale for and design of the Manhood 2 0 trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;71:18–32.

Bell L, Ullah S, Leslie E, Magarey A, Olds T, Ratcliffe J, et al. Changes in weight status, quality of life and behaviours of South Australian primary school children: results from the Obesity Prevention and Lifestyle (OPAL) community intervention program. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1338.

Berge JM, Jin SW, Hanson C, Doty J, Jagaraj K, Braaten K, et al. Play it forward! A community-based participatory research approach to childhood obesity prevention. Fam Syst Health. 2016;34(1):15–30.

Bottorff JL, Huisken A, Hopkins M, Nesmith C. A RE-AIM evaluation of Healthy Together: a family-centred program to support children’s healthy weights. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1754.

Bottorff JL, Huisken A, Hopkins M, Friesen L. Scaling up a community-led health promotion initiative: lessons learned and promising practices from the Healthy Weights for Children Project. Eval Program Plann. 2021;87: 101943.

Brophy-Herb HE, Horodynski M, Contreras D, Kerver J, Kaciroti N, Stein M, et al. Effectiveness of differing levels of support for family meals on obesity prevention among head start preschoolers: the simply dinner study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):184.

Brown SA, Turner RE, Christensen C. Linking families and teens: randomized controlled trial study of a family communication and sexual health education program for rural youth and their parents. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69(3):398–405.

Dannefer R, Bryan E, Osborne A, Sacks R. Evaluation of the Farmers’ Markets for Kids programme. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(18):3397–405.

Exner-Cortens D, Wolfe D, Crooks CV, Chiodo D. A preliminary randomized controlled evaluation of a universal healthy relationships promotion program for youth. Can J Sch Psychol. 2020;35(1):3–22.

Fair ML, Kaczynski AT, Hughey SM, Besenyi GM, Powers AR. An initiative to facilitate park usage, discovery, and physical activity among children and adolescents in Greenville county, South Carolina, 2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E14.

Flattum C, Draxten M, Horning M, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Garwick A, et al. HOME Plus: Program design and implementation of a family-focused, community-based intervention to promote the frequency and healthfulness of family meals, reduce children’s sedentary behavior, and prevent obesity. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:53.

Garcia AL, Athifa N, Hammond E, Parrett A, Gebbie-Diben A. Community-based cooking programme ‘Eat Better Feel Better’ can improve child and family eating behaviours in low socioeconomic groups. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;74(2):190–6.

Gillespie J, Hughes A, Gibson AM, Haines J, Taveras E, Reilly JJ. Protocol for Healthy Habits Happy Homes (4H) Scotland: feasibility of a participatory approach to adaptation and implementation of a study aimed at early prevention of obesity. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6): e028038.

Gittelsohn J, Dennisuk LA, Christiansen K, Bhimani R, Johnson A, Alexander E, et al. Development and implementation of Baltimore Healthy Eating Zones: a youth-targeted intervention to improve the urban food environment. Health Educ Res. 2013;28(4):732–44.

Gittelsohn J, Trude AC, Poirier L, Ross A, Ruggiero C, Schwendler T, et al. The impact of a multi-level multi-component childhood obesity prevention intervention on healthy food availability, sales, and purchasing in a low-income urban area. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Electronic Resource]. 2017;14(11):10.

Grier K, Hill JL, Reese F, Covington C, Bennette F, MacAuley L, et al. Feasibility of an experiential community garden and nutrition programme for youth living in public housing. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(15):2759–69.

Hill AV, Mistry S, Paglisotti TE, Dwarakanath N, Lavage DR, Hill AL, et al. Assessing feasibility of an adolescent relationship abuse prevention program for girls. J Adolesc. 2022;94(3):333–53.

Hoffman AM, Branson BG, Keselyak NT, Simmer-Beck M. Preventive services program: a model engaging volunteers to expand community-based oral health services for children. J Dent Hyg. 2014;88(2):69–77.

Holland KM, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Cruz JD, Massetti GM, Mahendra R. A qualitative evaluation of the 2005–2011 National Academic Centers of Excellence in Youth Violence Prevention Program. Eval Program Plann. 2015;53:80–90.

Iachini AL, Beets MW, Ball A, Lohman M. Process evaluation of “Girls on the Run”: exploring implementation in a physical activity-based positive youth development program. Eval Program Plann. 2014;46:1–9.

Jacobs J, Strugnell C, Allender S, Orellana L, Backholer K, Bolton KA, et al. The impact of a community-based intervention on weight, weight-related behaviours and health-related quality of life in primary school children in Victoria, Australia, according to socio-economic position. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):2179.

Jung ME, Bourne JE, Gainforth HL. Evaluation of a community-based, family focused healthy weights initiative using the RE-AIM framework. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15(1):13.

Maitland N, Williams M, Jalaludin B, Allender S, Strugnell C, Brown A, et al. Campbelltown - changing our future: study protocol for a whole of system approach to childhood obesity in South Western Sydney. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1699.

Mathews DR, Kunicki ZJ, Colby SE, Franzen-Castle L, Kattelmann KK, Olfert MD, et al. Development and testing of program evaluation instruments for the iCook 4-H curriculum. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2019;51(3):S21–9.

McIntosh B, Daly A, Masse LC, Collet JP, Higgins JW, Naylor PJ, et al. Sustainable childhood obesity prevention through community engagement (SCOPE) program: evaluation of the implementation phase. Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;93(5):472–8.

Miller E, Jones KA, Culyba AJ, Paglisotti T, Dwarakanath N, Massof M, et al. Effect of a community-based gender norms program on sexual violence perpetration by adolescent boys and young men: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2028499.

Morrison-Beedy D, Jones SH, Xia Y, Tu X, Crean HF, Carey MP. Reducing sexual risk behavior in adolescent girls: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(3):314–21.

Otto MW, Rosenfield D, Gorlin EI, Hoyt DL, Patten EA, Bickel WK, et al. Targeting cognitive and emotional regulatory skills for smoking prevention in low-SES youth: A randomized trial of mindfulness and working memory interventions. Addict Behav. 2020;104: 106262.

Overcash F, Ritter A, Mann T, Mykerezi E, Redden J, Rendahl A, et al. Impacts of a vegetable cooking skills program among low-income parents and children. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018;50(8):795–802.

Pawlowski CS, Winge L, Carroll S, Schmidt T, Wagner AM, Nortoft KPJ, et al. Move the neighbourhood: study design of a community-based participatory public open space intervention in a Danish deprived neighbourhood to promote active living. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):481.

Rhew IC, Hawkins JD, Murray DM, Fagan AA, Oesterle S, Abbott RD, et al. Evaluation of community-level effects of communities that care on adolescent drug use and delinquency using a repeated cross-sectional design. Prev Sci. 2016;17(2):177–87.

Robertson S, Woodall J, Henry H, Hanna E, Rowlands S, Horrocks J, et al. Evaluating a community-led project for improving fathers’ and children’s wellbeing in England. Health Promot Int. 2018;33(3):410–21.

Robinson WT, Seibold-Simpson SM, Crean HF, Spruille-White B. Randomized trials of the teen outreach program in Louisiana and Rochester. New York Am J Public Health. 2016;106:S39–44.

Roding D, Soellner R, Reder M, Birgel V, Kleiner C, Stolz M, et al. Study protocol: a non-randomised community trial to evaluate the effectiveness of the communities that care prevention system in Germany. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1927.

Salazar AM, Haggerty KP, de Haan B, Catalano RF, Vann T, Vinson J, et al. Using communities that care for community child maltreatment prevention. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86(2):144–55.

Salazar AM, Haggerty KP, Briney JS, Vann T, Vinson J, Lansing M, et al. Assessing an adapted approach to communities that care for child maltreatment prevention. J Soc Soc Work Res. 2019;10(3):349–69.

Seirawan H, Parungao K, Habibian M, Slusky N, Edwards C, Artavia M, et al. The Children’s Health and Maintenance Program (CHAMP): an innovative community outreach oral health promotion program: a randomized trial. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2021;49(2):192–200.

Skouteris H, Hill B, McCabe M, Swinburn B, Busija L. A parent-based intervention to promote healthy eating and active behaviours in pre-school children: evaluation of the MEND 2–4 randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Obes. 2016;11(1):4–10.

Smith C, Clark AF, Wilk P, Tucker P, Gilliland JA. Assessing the effectiveness of a naturally occurring population-level physical activity intervention for children. Public Health. 2020;178:62–71.

Strunin L, Wulach L, Yang GJ, Evans TC, Hamdan SU, Davis GL, et al. Preventing cancer: a community-based program for youths in public housing. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:S83–8.

Trude ACB, Kharmats AY, Jones-Smith JC, Gittelsohn J. Exposure to a multi-level multi-component childhood obesity prevention community-randomized controlled trial: patterns, determinants, and implications. Trials [Electronic Resource]. 2018;19(1):287.

Umstattd Meyer MR, Bridges Hamilton CN, Prochnow T, McClendon ME, Arnold KT, Wilkins E, et al. Come together, play, be active: Physical activity engagement of school-age children at Play Streets in four diverse rural communities in the U.S. Prevent Med. 2019;129:105869.

Vinck J, Brohet C, Roillet M, Dramaix M, Borys JM, Beysens J, et al. Downward trends in the prevalence of childhood overweight in two pilot towns taking part in the VIASANO community-based programme in Belgium: data from a national school health monitoring system. Pediatr Obes. 2016;11(1):61–7.

White AA, Colby SE, Franzen-Castle L, Kattelmann KK, Olfert MD, Gould TA, et al. The iCook 4-H Study: an intervention and dissemination test of a Youth/Adult Out-of-School program. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2019;51(3):S2–20.

Kwan BM, McGinnes HL, Ory MG, Estabrooks PA, Waxmonsky JA, Glasgow RE. RE-AIM in the real world: use of the RE-AIM framework for program planning and evaluation in clinical and community settings. Front Public Health. 2019;7:345.

Baum F, MacDougall C, Smith D. Participatory action research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(10):854–7.

World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight 2021 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

Olds T, Maher C, Zumin S, Péneau S, Lioret S, Castetbon K, et al. Evidence that the prevalence of childhood overweight is plateauing: data from nine countries. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(5–6):342–60.

NRF Collaboration. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2627–42.

World Health Organization. Population-based approaches to childhood obesity prevention. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

Hariton E, Locascio JJ. Randomised controlled trials - the gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: randomised controlled trials. BJOG. 2018;125(13):1716.

Tarquinio C, Kivits J, Minary L, Coste J, Alla F. Evaluating complex interventions: Perspectives and issues for health behaviour change interventions. Psychol Health. 2015;30(1):35–51.

Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374: n2061.

Crespi C. Design and Analysis of Cluster Randomized Trials. In: Textbook of Clinical Trials in Oncology A statistical perspective. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2019. p. 203–37.

Benjamin-Chung J, Arnold BF, Berger D, Luby SP, Miguel E, Colford JM Jr, et al. Spillover effects in epidemiology: parameters, study designs and methodological considerations. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(1):332–47.

De Vocht F, Katikireddi SV, McQuire C, Tilling K, Hickman M, Craig P. Conceptualising natural and quasi experiments in public health. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21(1):32.

Bärnighausen T, Tugwell P, Røttingen JA, Shemilt I, Rockers P, Geldsetzer P, et al. Quasi-experimental study designs series-paper 4: uses and value. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:21–9.

Bärnighausen T, Røttingen JA, Rockers P, Shemilt I, Tugwell P. Quasi-experimental study designs series-paper 1: introduction: two historical lineages. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:4–11.

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350: h1258.

Hawkins JD, Brown EC, Oesterle S, Arthur MW, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Early effects of communities that care on targeted risks and initiation of delinquent behavior and substance use. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(1):15–22.

Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen AJ, Guzman JR, et al. Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles. Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity. 2017;3:32–5.

Yonas MA, Burke JG, Rak K, Bennett A, Kelly V, Gielen AC. A picture’s worth a thousand words: engaging youth in CBPR using the creative arts. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2009;3(4):349–58.

Belone L, Lucero JE, Duran B, Tafoya G, Baker EA, Chan D, et al. Community-based participatory research conceptual model: community partner consultation and face validity. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(1):117–35.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Myriam Robert who contributed to the screening process.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This project received no third part funding, but was conducted as part of a Master thesis at the MSc PH program of the LMU.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CJS supervised the project. Five authors (BB, MC, JH, SV, CJS) were involved in the protocol development. BB and CJS developed the search strategy and BB conducted the database research. All authors participated in the title abstract screening and BB performed the snowballing approach on found reviews. The full text screening was done by BB, JH, PS and SV; BB and JH extracted the data. BB generated the narrative data synthesis which was supervised by and discussed with CJS and reviewed by the co-authors (MC, JH, SV). BB prepared a draft of the manuscript under the supervision of CJS. All authors commented, revised and reviewed the manuscript (MC, JH, SV, CJS). The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. Only data from already published data was used in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The “Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung” (BzGA; English: German Federal Center for Health Education) provided the funding for the evaluation of an ISCHP in Munich. MC, JH, CJS and SV are involved in this evaluation of an ISCHP in Munich. PS is a doctoral candidate in the Research Training Group “PrädiktOren und Klinische Ergebnisse bei depressiven ErkrAnkungen in der hausärztLichen Versorgung (POKAL, DFG-GRK 2621)” (Predictors and Clinical Outcomes of Depressive Disorders in Primary Care) POKAL, a member of the German Research Foundation (DFG). BB has no competing interests to declare.

Author list: Bettina Bader, Michaela Coenen, Julia Hummel, Petra Schoenweger, Stephan Voss, and Caroline Jung-Sievers.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bader, B., Coenen, M., Hummel, J. et al. Evaluation of community-based health promotion interventions in children and adolescents in high-income countries: a scoping review on strategies and methods used. BMC Public Health 23, 845 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15691-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15691-y