Abstract

Background

There are public health concerns about an increased risk of mortality after release from prison. The objectives of this scoping review were to investigate, map and summarise evidence from record linkage studies about drug-related deaths among former adult prisoners.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychINFO and Web of Science were searched for studies (January 2011- September 2021) using keywords/index headings. Two authors independently screened all titles and abstracts using inclusion and exclusion criteria and subsequently screened full publications. Discrepancies were discussed with a third author. One author extracted data from all included publications using a data charting form. A second author independently extracted data from approximately one-third of the publications. Data were entered into Microsoft Excel sheets and cleaned for analysis. Standardised mortality ratios (SMRs) were pooled (where possible) using a random-effects DerSimonian-Laird model in STATA.

Results

A total of 3680 publications were screened by title and abstract, and 109 publications were fully screened; 45 publications were included. The pooled drug-related SMR was 27.07 (95%CI 13.32- 55.02; I 2 = 93.99%) for the first two weeks (4 studies), 10.17 (95%CI 3.74–27.66; I 2 = 83.83%) for the first 3–4 weeks (3 studies) and 15.58 (95%CI 7.05–34.40; I 2 = 97.99%) for the first 1 year after release (3 studies) and 6.99 (95%CI 4.13–11.83; I 2 = 99.14%) for any time after release (5 studies). However, the estimates varied markedly between studies. There was considerable heterogeneity in terms of study design, study size, location, methodology and findings. Only four studies reported the use of a quality assessment checklist/technique.

Conclusions

This scoping review found an increased risk of drug-related death after release from prison, particularly during the first two weeks after release, though drug-related mortality risk remained elevated for the first year among former prisoners. Evidence synthesis was limited as only a small number of studies were suitable for pooled analyses for SMRs due to inconsistencies in study design and methodology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The world prison population size was over 10.7 million in 2021 or 140 per 100,000 of population [1]. However, the prison population is estimated to be more than 11.5 million when we take into account statistical information about prisoners which is unavailable or unrecognised internationally or is missing from published national prison population sizes [1]. Prison population rates vary by country and region. For example, the USA has the highest prison population—over 2 million people, equivalent to a rate of 629 per 100,000 [1]. There are higher rates of mental and physical health problems in prison populations compared to the general population, and substance use disorders are common in people who are committed to prison [2, 3]. There is a risk of disruption to treatment and care and a deterioration in health when former prisoners transition from prison to living in the community [2]. Furthermore, negative health effects may be compounded by post-release experiences of former prisoners including loss of social support, enduring stigma, financial insecurity and difficulties obtaining stable housing [4].

There are concerns about the increased risk of mortality after release from prison and the contribution of drug-related causes to deaths in former prisoners [5,6,7]. A review in 2010 reported that 76% of deaths in the first 2 weeks after release and 59% of deaths within the first 3 months of release were due to drug-related causes [7]. There is a need to examine the range of potential factors that may contribute to the increased risk of drug-related deaths after release from prison, including decreased tolerance following relative abstinence in prison and the concurrent use of multiple drugs [8]. Observational studies investigating the risk of mortality after prison release often use large administrative datasets to link prison and death records. An updated review of the evidence in this area, including the extent of the literature, methodologies, findings and gaps in knowledge is warranted and a scoping review approach has been chosen to map key concepts and summarise evidence in this field. This scoping review updates and maps research evidence in the area of record linkage studies of drug-related deaths among former adult prisoners, and identifies and profiles at-risk former prisoners. The findings are discussed in terms of their contribution to potential interventions and to informing future research and policy. This review was undertaken as part of a work programme in the Administrative Data Research Centre, Northern Ireland and in response to concerns from public health, criminal justice, voluntary and community groups and wider society about prisoner health and well-being in Northern Ireland after release from prison.

Methods

We chose to conduct a scoping review because of the broader scope of our review that included a focus on how the research was conducted and differences in methodologies used among record-linkage studies in this research area. This broader scope was informed largely by the results of previous systematic reviews/meta-analysis regarding reported high levels of heterogeneity [5,6,7]. The methods used to conduct this scoping review have been published previously as a protocol [9] and a summary of the methodology is provided here. This review followed the first five stages of the framework for conducting scoping reviews by Arksey and O’Malley [10] and adhered to the guidance developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) and the JBI Collaboration. For example, as recommended by the JBI, the population, concept and context (PCC) guide was incorporated into the scoping review title, research questions and inclusion criteria [11]. In addition, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist and guidance was used to structure and report this review [12]. This scoping review was structured to meet the requirements of the PRISMA-ScR checklist. A completed PRISMA-ScR checklist (used to report this work) has been provided as supplementary material in this scoping review.

Stage 1: identifying the research question

The following questions were addressed by the scoping review:

-

1. What is the scope of the literature on record linkage studies of drug-related deaths among former adult prisoners who have been released to the community?

-

2. How is research conducted on this topic?

-

3. What methodologies are used?

-

4. What are the findings in relation to mortality?

-

5. Where are the knowledge gaps on this topic?

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

In order to summarise the most recent evidence, the start date of 2011 was chosen for this scoping review. Four bibliographic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychINFO and Web of Science) were searched for studies from January 2011 to September 2021 using keywords and index headings (modified as required for each database). The search terms related to ‘mortality’, ‘drugs’ and ‘ex-prisoner’ (and their variants). The review focused on drug-related deaths and as such, the search strategy included a broad range of terms including substance-related disorders, drug overdose and drug misuse. The full list is found in appendices 1, 2, 3, and 4. The search strategy for MEDLINE was developed by JAC and MD with assistance from the Subject Librarian for the School of Medicine, Dentistry and Biomedical Sciences in Queen’s University Belfast, and was published with the review protocol [9]. JAC and MD developed search strategies for EMBASE, PsychINFO and Web of Science, and all search strategies used in this review have been provided as supplementary material (appendices 1, 2, 3, and 4). The reference lists of included studies were screened by JAC to identify any additional publications. Due to the absence of resources for translation, all search strategies were limited to publications in the English language. There was no geographical restrictions on studies.

Stage 3: study selection

All bibliographic database searches were performed by JAC on 15th September 2021 and the results were combined in Endnote Reference Manager where duplicate publications were subsequently removed. JAC and IO independently screened all titles and abstracts using the pre-defined inclusion criteria and excluded any non-eligible publications. Publications were screened using criteria defined in Table 1. Publications were screened in full if an abstract was not available and/or there was uncertainty over inclusion. Subsequently, JAC and IO independently screened full publications for inclusion and any discrepancies between JAC and IO regarding eligibility were resolved in a discussion between JAC and MD during which a unanimous decision was made. No authors of publications were contacted during this process.

Stage 4: charting the data

A draft charting form was piloted as part of the protocol development stage. As part of the review process, the charting form was retested by JAC and EP (the final data charting form used is provided in appendix 5). JAC independently extracted information from all included publications using this data charting form. The accuracy and consistency of the recorded information was checked by using a second reviewer (EP) to independently extract information for a proportion of the included publications (n = 14) and resolving any discrepancies via discussion by team members. In addition, JAC and MD met weekly and discussed the studies in the review particularly for their fit with the pre-specified inclusion criteria and the charting procedure.

Stage 5: collating, summarising and reporting the results

Information was extracted from the charting forms and entered into Microsoft Excel sheets for data management and analysis. Data in the Microsoft Excel sheets were subsequently cleaned and extracted information was summarised. The data were analysed and presented in a format that was designed to answer the scoping review questions and organised according to the main conceptual categories including methodology, key findings and gaps in the research. All descriptive tables and figures for this review were prepared using these data contained in the Microsoft Excel sheets. We reported mortality outcomes following release from prison in terms of, for example, crude mortality rates (CMRs) and standardised mortality ratios (SMRs). Where possible, age, sex/gender and race/ethnicity, time period examined after prison release and information on specific drugs were reported in relation to drug-related mortality. SMRs for drug-related deaths after release from incarceration were pooled statistically, where possible. The log SMR was determined as well as the Standard Error (SE) of the log SMR from the published SMR and confidence intervals (CIs). In meta-analysis, the consistency of effects across studies should be assessed [13]. The random-effects DerSimonian-Laird model was used. In STATA version 16.1 [StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA], the meta command was used to compute effect sizes and summarise data and produce forest plots. The heterogeneity was measured using the I2 squared statistic and testing using a formal chi-squared test for heterogeneity. Meta-analyses are not a usual feature of the methodology of scoping reviews [10, 11], however, exploratory meta-analyses were conducted following this scoping review to deepen the level of critical analysis by, for example, assessing in a quantitative way, the consistency of effects. Meta-analyses were performed posteriori and were not planned in the study protocol [9].

Patient and public involvement

Our empirical study of prisoner post-release mortality and this scoping review were initiated in response to concerns about the increasing number of drug-related deaths generally from the UK Chief Medical Officers (CMOs) including the CMO for Northern Ireland. We continue to consult with, and involve, key prison health care staff including the Clinical Director of Healthcare in Prisons in Northern Ireland in our ongoing programme of prison health research (co-author of this paper).

Results

Study selection

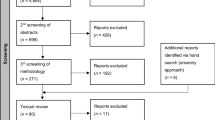

The search strategy identified a combined total of 4397 publications across four bibliographic databases. Using the Endnote duplicate tool, 717 duplicate publications were removed. A total of 3680 publications were screened by title and abstract; 109 publications were deemed to meet eligibility criteria and full-text publications were screened by two authors (reviewer 1 fully screened 105 publications and reviewer 2 fully screened 36 publications i.e. there was some overlap of screened publications). Authors noted that some remaining duplicate articles were among the publications excluded at this stage (9 remaining duplicates removed). There was agreement between reviewers to include 23 publications and exclude 49 publications. There was disagreement or uncertainty between reviewers about 28 publications and these publications were fully screened by reviewer 3 and resolved via discussion with reviewer 1; 25 of these 28 publications were included. A total of 48 publications were included at this stage and the reference lists of included publications were screened, resulting in the addition of one further publication. Four publications were excluded during the data extraction stage after discussion between reviewer 1 and reviewer 3. The reasons for exclusion of publications were as follows: summary of another paper included in review [14], no drug-related deaths [15], not people released from prison [16] and an ambiguity over whether a study included individuals who had been recently released from, or admitted to, jail, prison or a detention facility [17]. Following this review process, a total of 45 publications were included. A flow diagram for each stage is presented in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics and methods for included studies are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Research questions

The data were analysed in a format that was designed to answer the review questions, as presented below.

-

1. What is the scope of the literature on record linkage studies of drug-related deaths among former adult prisoners who have been released to the community?

The included studies (n = 45) were published across 25 different journals. The five most common journals that published studies in this area were Addiction (n = 12), Drug and Alcohol Dependence (n = 7), American Journal of Public Health (n = 2), JAMA Psychiatry (n = 2) and Public Health Reports (n = 2) (Table 2). The remaining included studies (n = 20) were published in 20 different journals. The geographical distribution of the included studies, by location of the custody setting, shows a total of 9 countries/regions (appendix 6). The most common locations were the USA (n = 24) and Australia (n = 7). Other locations were Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Taiwan and the UK. One publication included both USA and Australia by way of comparing cohorts [18]. The search strategy included January 2011 to September 2021 in order to summarise the most recent evidence (the distribution of publications across this time period is presented in appendix 6).

This scoping review focused on studies of mortality risk during the time period after release from incarceration—the number of years and months following release from incarceration were provided in 60% of studies (n = 27) (Table 3). Information about incarceration dates was provided in half of those studies without release dates (n = 9/18). The earliest reported period of release was 1988 to 2002 (in a study by Kinner et al. 2011) and the study with the most recent year analysed data from 2018 [19]. The studies with the longest release period covered a total of 16 years, which included releases between 2000 and 2015 [20, 21] and the study with the shortest time period was a follow-up of all prisoners released on a specified date in July 2007 [22]. For studies which provided information about incarceration dates (rather than specified release dates), two [23, 24] used a single incarceration date (specified in June 1991) as the index date for follow-up, whereas all other studies used either a single year or range of years. Although some of the key questions in this scoping review were around methodology, the extent to which included studies reported key characteristics varied. For example, in all studies, sex or gender was reported in some format throughout various sections of the paper, whereas age and race or ethnicity were less well documented. Approximately 31% of included studies did not report the age of their study population (n = 14) and 31% did not report race or ethnicity in any format (n = 14) (Table 2 and appendix 7).

-

2. How is research conducted on this topic?

The most commonly reported study designs were retrospective cohort studies (n = 16), prospective cohort study studies (n = 5) and nested case–control studies (n = 3) (Table 2). Several included studies did not state the study design (n = 7). The type of data used by included studies to investigate prison release and mortality are shown in Table 3. Prison data was often obtained from national prison or criminal registries, department of correction/correctional services or records, or records from single prison systems, for example, individuals released from one county jail. Mortality data used by included studies to determine drug-related death was often obtained from the national death index or national death registries or regional (for example, USA State) death records.

Study parameters such as number of people released, number of releases (as an individual may have been committed and released more than once during the study period) or person-years of follow-up are reported in Table 2, and included studies differed in size. The study with the largest number of people reported that 229,274 were released over a 16-year time period (between 2000 and 2015) – data from this retrospective cohort study of people released from prison was analysed and presented in two separate papers [25, 26].

The review found that the terminology that was used in the included studies to report death outcomes varied; the most commonly used terms were overdose deaths, opioid overdose deaths, opioid-related overdose deaths, drug-related deaths and similar, less frequently used variants including death from drug-related infections, drug toxicity and contributing substance use–related cause of death. Approximately 64% of the published studies (n = 29) used the codes from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) to describe cause of mortality (Table 3). Data linkage (or similar meaning terms) was an inclusion criterion in this scoping review. The methods used for data linkage included probabilistic linkage/matching/score (n = 17), deterministic linkage (n = 2), deterministic and probabilistic linkage (n = 2), personal identifiers or unique identification linkage in methods (n = 11), and combinations of name, date of birth, sex or gender and race or ethnicity (n = 5). In several studies (n = 8) linkage methods were not stated (Table 3).

Only four studies reported the use of a quality assessment checklist or technique. All four of these studies used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist [20, 27,28,29]. The STROBE guideline provides a checklist of items about the planning and conduct of epidemiological observational studies and best practice requires researchers and authors to include a completed checklist in their reports and papers. Only one study, Chang et al. 2015, provided a copy of the STROBE statement [27].

-

3. What methodologies are used?

The included studies examined various time periods after release from prison and it was common for studies to examine more than one time period (n = 19) (Table 3). Commonly investigated time periods included the first two weeks after release (n = 11), the first month (including studies examining intervals up to one month e.g. 1–2 weeks and 3–4 weeks) (n = 14) and the first year after release (including studies examining intervals up to one year e.g. up to 4 weeks, after 4 weeks up to 6 months, after 6 months up to 1 year, all follow-up to 1 year) (n = 16). During follow-up any re-committals would reduce the at-risk period for mortality as the individual would be in custody rather than in the community, and 60% of included studies took into consideration person-time at risk in the community time and during any subsequent re-incarcerations (n = 27). The methods used for dealing with repeated incarcerations included person-time being excluded at re-incarceration i.e. person-time was calculated from the day of release from prison until re-incarceration. Another approach used excluded time during a subsequent incarceration, whereas the time between the next release and death, another incarceration, or the end of the study was included. Other methods used the most recent prison release date/index release was that closest to death or calculated person-time following every release during follow-up until death, re-incarceration or the end of study follow-up. In one study, time periods of 4 weeks and 1 year from the date of first release were used regardless of reimprisonment within these time frames, therefore this method did not exclude time whilst in custody [30]. Another study, coded each re-incarceration after the index release date as an ‘additional post-release booking’ to determine any effect on survival [25].

-

4. What are the findings in relation to mortality?

A summary of the drug-related mortality outcomes reported in the included studies is provided in appendix 8. Studies reporting SMR by characteristics and time after release are shown in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. CMRs reported by time after release are shown in Table 6. The pooled SMRs across the included studies, grouped by time periods examined after release, are shown in Table 7. The pooled drug-related SMR was 6.99 (95% CI 4.13–11.83; I2 = 99.14%) for any time after release (5 studies), 27.07 (95% CI 13.32–55.02; I2 = 93.99%) for the first two weeks (4 studies), 10.17 (95% CI 3.74–27.66; I2 = 83.83%) for the first 3–4 weeks (3 studies) and 15.58 (95% CI 7.05–34.40; I2 = 97.99%) for the first 1 year after release (3 studies) (Table 7). In all studies the SMR was significantly above 1, but in some, this was much higher than others. These results suggest differences in each study. There was a high level of heterogeneity and this must be considered when interpreting the pooled estimates as it may reflect substantial inter-study differences in study design, setting or population. CMRs were not pooled for specific time periods due to a low number of studies reporting these findings. Forest plots are provided in appendix 9. A summary of variables investigated in included studies is provided in appendix 10.

-

5. Where are the knowledge gaps on this topic?

Our review suggests that knowledge gaps in this topic revolve around methodological differences in study design and limitations in the capacity to synthesise the evidence. Only a limited number of the 45 eligible studies were suitable for inclusion in the pooled analyses for SMRs – there is a need for increased consistency in the use of observational study methodology about mortality among former prisoners. More rigorous reporting of characteristics of former prisoners would allow subgroup analyses to profile those people most at-risk after prison release. For example, reporting characteristics of former prisoners, in terms of age, married or single, health etc. would give a fuller presentation of the results. Our review captured studies from USA, Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Taiwan and the UK and pointed to a distinct lack of studies undertaken in low and middle income (LMIC) countries. Clearly, therefore, there is a need for studies to be conducted of this population in LMIC countries in order to understand the extent of global drug-related mortality among people following release from prison.

Discussion

This scoping review maps and summarises research evidence from record linkage studies about drug-related deaths among former adult prisoners and the extent to which drug-related causes contribute to post-release prisoner mortality. The research questions in this review focused on the scope of the literature, methodologies used in observational data-linkage studies and the most recent findings in relation to mortality (published between 2011 and 2021). This scoping review found an increased risk of drug-related death after release from prison, particularly in the first two weeks after release, although the drug-related mortality risk remained elevated for the first year among former prisoners. However, despite this review identifying 45 relevant publications, only a limited number of studies were included in the pooled analyses for SMRs due to differences in study design (for example, time periods examined after release) and methodologies used which has significantly limited evidence synthesis. In addition, we found high levels of heterogeneity in our pooled analyses meaning that our interpretation of the pooled estimates is more hesitant.

The findings of our scoping review are supported by previous literature mapping this topic. A recent scoping review by Mital et al. described the relationship between incarceration history (custody in a jail or prison facility) and opioid overdose in North America, including 18 studies published between 2001 and 2019, with the scoping review methodology following guidance by Levac et al. [63, 64]. The review reported four important findings; (1) an increased risk of opioid overdose among formerly incarcerated people; (2) an increased risk of opioid overdose was associated with some demographic, substance use, and incarceration-related characteristics (including substance use disorders and mental health issues); (3) incarceration history was identified as a risk factor for opioid overdose among individuals who inject opioids and (4) opioid overdose was suggested as the leading cause of death in people who have been formerly incarcerated [63].

The results of this review in terms of an increased mortality risk after prison release concurs with the findings previously published in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. It is concerning that post-release mortality risk is high. Collectively, the reviews appear to indicate that post-release mortality has persisted over time. For example, a previous systematic review pooled SMRs from studies which used record linkage methods to examine deaths in ex-prisoners between 1998 and 2011, reporting SMRs for drug-related death of 32.2 (95% CI 22.8–45.4) for < 1 year, 26.2 (95% CI 6.4–107.3) for ≥ 1 year and 27.3 (95% CI 9.8–76.0) for any time after release [6]. A separate systematic review of publications between 1980 and 2011 explored the literature on studies of mortality in released prisoners using linkage of prisoner and mortality databases, and reported all-cause SMR, ranging from 1.0 to 9.4 in males and from 2.6 to 41.3 in females [5]. Furthermore, similar to our findings, where the drug-related death risk was highest in the first two weeks after release; a meta-analysis of mortality during the 12 weeks after prison release reported an increased risk of drug-related mortality during the first 2 weeks after prison release compared to the subsequent 10 weeks (however, the mortality risk was elevated during the first 4 weeks) [7].

Kinner et al., Merrall et al. and Zlodre and Fazel, all reported high levels of heterogeneity, for example between countries [7], in study design [5, 6], and in analysis and findings of publications [6]. In our scoping review, differences in the study design, methodologies and findings of included studies limited the degree to which studies could be synthesised meaningfully. The included studies examined various time periods after release from prison and this limited the number of studies included in the pooled analyses in this review. Differences were also found in study design, i.e. retrospective cohort, prospective cohort and nested case–control study designs, but differences were also found in methodologies, for example in the approaches used for determining the time at-risk during follow-up. During re-incarceration, re-committals would reduce the at-risk period for drug-related mortality as the individual would be in custody rather than in the community. Other differences included various types of data used by included studies to determine mortality (for example, national and regional death records) and prison release (for example, national prison registries and single prison records). The type and geographical distribution of death records used in the study would likely have affected the number of missed deaths, for example if mortality records covered one country and the death occurred outside of this border. The study size differed in the included publications and the size of the prison population(s) and location(s) of prison(s) would affect the generalisability of the study findings. The terminology used to describe or define drug-related deaths differed between studies, with some studies using ICD codes and definitions. The definition used to describe drug-related deaths may have an effect on the findings, for example combining multiple ICD codes for drug-related deaths in the definition would be more inclusive compared to very specific definitions.

The reporting of characteristics of individuals varied between included studies. Gender/sex was reported in all studies, but age and race/ethnicity were only reported in one-third of papers, making it difficult to contextualise the findings. Approximately 9% of included studies stated the use of a quality assessment checklist or technique and in only one study was a copy of the STROBE statement provided as an appendix. Adequate reporting of research facilitates the assessment of published studies and following recommended guidelines in the reporting of research allows rigour and transparency in the process. In summary, this review suggests a need for a more consistent methodology and rigorous reporting of observational studies about mortality among former prisoners.

Study strengths and limitations

Although meta-analyses are not consistent with the methodology of scoping reviews [10, 11], this scoping review included exploratory meta-analyses. We conducted a scoping review (rather than a systematic review) because we wanted to scope and search broadly and at the same time deepen the level of critical analysis where there was an opportunity to do so. For example, the review included a focus on how record linkage research was conducted, and on differences in methodologies that were used among record-linkage studies in this research area. This broader focus stemmed largely from the results of previous systematic reviews/meta-analysis that reported high levels of heterogeneity [5,6,7]. Our scoping review summarised the methodologies and findings narratively, and the accompanying meta-analyses added to this narrative by explaining high levels of heterogeneity in our pooled analyses, and showing differences across studies. This review recommends that a more consistent approach to methodology and reporting is followed in the future. This scoping review has several strengths. This is the first scoping review of record linkage studies about drug-related deaths among former adult prisoners. The methods followed the first five stages of the framework for conducting scoping reviews by Arksey and O’Malley [10] and adhered to the guidance developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) and the JBI Collaboration. The methods for this scoping review were previously published in a protocol allowing transparency and forward planning [9]. Modifications from the original protocol have been stated in this review, and in a deviation from that stated in the protocol, data were independently extracted by one reviewer, with a proportion of papers checked by using a second reviewer due to time constraints. Using this approach allowed a check of the accuracy and consistency of the recorded information. There are some limitations to this review, the search strategy was limited to publications available in English due to resources for translation and the review did not include a search of the grey literature which may limit the interpretation of the findings.

Future research and policy

This scoping review focused on former prisoners. However reviews on other prisoner groups, such as prisoners on remand or probation, would be of benefit. Prisoners have higher rates of mental and physical health problems compared to the general population, and substance use disorders are common in people who are committed to prison. Research on mental and physical health conditions, substance use disorders, and physical and mental ill health comorbidity in people released from prison could help profile risk after release. As part of this scoping review process, authors identified one randomised controlled trial in Australia and one randomized controlled pilot trial after prison release in England, but these publications were excluded at the full screening stage [65, 66]. The NALoxone InVEstigation (N-ALIVE) pilot trial tested feasibility measures for randomized provision of naloxone-on-release to eligible prisoners and demonstrated the feasibility of recruiting prisons and consenting of prisoners [65]. A randomised controlled trial of a service brokerage intervention for adult former prisoners involved an intervention group receiving a personalised booklet with their health status and appropriate community health services, and telephone contact for each week in the first month after release to assess any health needs and health service utilisation (control arm received usual care) [66]. A separate review of trials in former prisoners after release would provide evidence to help guide the development of future research in this area.

This review was undertaken in response to concerns from public health, criminal justice, voluntary and community groups and wider society about prisoner health and well-being in Northern Ireland after release from prison. Our findings suggest the need for formalised joined-up working and interagency collaboration regarding the way in which people released from prison are supported, and an ongoing review and consideration of interventions and service responses designed to reduce drug-related deaths among this group, including novel service responses such as overdose centres, transition clinics and drug consumption rooms [67, 68]. It is clear from the available evidence that the transition from prison to community is an at-risk period and there is need for sustained joined-up service responses and support that help people released from prison to negotiate this transition.

Conclusions

This scoping review found an increased risk of drug-related death after release from prison, particularly in the first two weeks after release, although the drug-related mortality risk remained elevated for the first year among former prisoners. Our results are of concern as we show that post-release mortality risk is still high despite similar findings having been reported in the literature more than a decade ago. This scoping review has detailed examples of differences in study design and methodology in included studies which has significantly limited evidence synthesis. This review suggests a need for a more consistent methodology and rigorous reporting of observational studies about mortality among former prisoners.

Availability of data and materials

Our submitted paper is a review and does not contain raw data in the usual meaning of that term. However, we have included, as a supplementary file, a data charting form showing all data fields that were extracted from the full texts of eligible papers.

Abbreviations

- CMOs:

-

Chief Medical Officers

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- CMRs:

-

Crude mortality rates

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- PRISMA-ScR:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews

- SE:

-

Standard Error

- SMRs:

-

Standardised mortality ratios

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

References

Fair and Walmsley, World Prison Population List, thirteenth edition. World prison brief. Institute for Criminal Policy Research, 2021.

Bradshaw R, Pordes BAJ, Trippier H, et al. The health of prisoners: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2017;356:j1378.

Fazel S, Yoon IA, Hayes AJ. Substance use disorders in prisoners: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis in recently incarcerated men and women. Addiction. 2017;112:1725–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13877.

Brinkley-Rubinstein L. Incarceration as a catalyst for worsening health. Health Justice. 2013;1:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/2194-7899-1-3.

Zlodre J, Fazel S. All-cause and external mortality in released prisoners: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(12):e67-75.

Kinner SA, Forsyth S, Williams G. Systematic review of record linkage studies of mortality in ex-prisoners: why (good) methods matter. Addiction. 2013;108(1):38–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12010. (Epub 2012 Nov 19 PMID: 23163705).

Merrall EL, Kariminia A, Binswanger IA, Hobbs MS, Farrell M, Marsden J, Hutchinson SJ, Bird SM. Meta-analysis of drug-related deaths soon after release from prison. Addiction. 2010;105(9):1545–54.

World Health Organization. WHO. Regional Office for Europe. Preventing overdose deaths in the criminal-justice system. 2010. Updated reprint 2014.

Cooper JA, Onyeka I, O’Reilly D, Kirk R, Donnelly M. Record linkage studies of drug-related deaths among former adult prisoners who have been released to the community: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3):e056598 PMID: 35351720; PMCID: PMC8966574.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In: JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI, 2020. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö, Straus SE. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850. (Epub 2018 Sep 4 PMID: 30178033).

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses BMJ. 2003;327:557. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Gisev, N., S. Larney, J. Kimber, L. Burns, D. Weatherburn, A. Gibson, T. Dobbins, R. Mattick, T. Butler and L. Degenhardt. "Determining the impact of opioid substitution therapy upon mortality and recidivism among prisoners: a 22 year data linkage study Foreword." Trends Issues Crime Crim. Justice(498). 2015

Huber F, Merceron A, Madec Y, Gadio G, About V, Pastre A, Coupez I, Adenis A, Adriouch L, Nacher M. High mortality among male HIV-infected patients after prison release: ART is not enough after incarceration with HIV. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175740 PMID: 28453525; PMCID: PMC5409162.

Krawczyk N, Mojtabai R, Stuart EA, Fingerhood MI, Agus D, Lyons BC, Weiner JP, Saloner B. Opioid agonist treatment is highly protective against overdose death among a US statewide population of justice-involved adults. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(1):117–26.

Paseda O, Mowbray OK. Substance use related mortality among persons recently released from correctional facilities. J Evid-Based Soc Work. 2021;18(6):689–701.

Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Forsyth SJ, Stern MF, Kinner SA. Epidemiology of infectious disease-related death after release from prison, Washington State, United States, and Queensland, Australia: a cohort study. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(4):574–82.

Haas A, Viera A, Doernberg M, Barbour R, Tong G, Grau LE, Heimer R. Post-incarceration outcomes for individuals who continued methadone treatment while in Connecticut jails, 2014–2018. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;227:108937 Epub 2021 Jul 28. PMID: 34371235; PMCID: PMC8819627.

Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Sivaraman J, Rosen DL, Cloud DH, Junker G, Proescholdbell S, Shanahan ME, Ranapurwala SI. Association of restrictive housing during incarceration with mortality after release. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1912516 PMID: 31584680; PMCID: PMC6784785.

Ranapurwala SI, Shanahan ME, Alexandridis AA, Proescholdbell SK, Naumann RB, Edwards D Jr, Marshall SW. Opioid overdose mortality among former North Carolina inmates: 2000–2015. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(9):1207–13.

Huang YF, Kuo HS, Lew-Ting CY, Tian F, Yang CH, Tsai TI, Gange SJ, Nelson KE. Mortality among a cohort of drug users after their release from prison: an evaluation of the effectiveness of a harm reduction program in Taiwan. Addiction. 2011;106(8):1437–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03443.x. (Epub 2011 May 12 PMID: 21438941).

Spaulding AC, Seals RM, McCallum VA, Perez SD, Brzozowski AK, Steenland NK. Prisoner survival inside and outside of the institution: implications for health-care planning. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(5):479–87.

Spaulding AC, Sharma A, Messina LC, Zlotorzynska M, Miller L, Binswanger IA. A comparison of liver disease mortality with HIV and overdose mortality among Georgia prisoners and releasees: a 2-decade cohort study of prisoners incarcerated in 1991. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):e51-7.

Victor, G., C. Zettner, P. Huynh, B. Ray and E. Sightes. Jail and overdose: assessing the community impact of incarceration on overdose. 2021. Addiction 12.

Krawczyk N, Schneider KE, Eisenberg MD, Richards TM, Ferris L, Mojtabai R, Stuart EA, Casey Lyons B, Jackson K, Weiner JP, Saloner B. Opioid overdose death following criminal justice involvement: Linking statewide corrections and hospital databases to detect individuals at highest risk. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;213:107997 Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32534407.

Chang Z, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Fazel S. Substance use disorders, psychiatric disorders, and mortality after release from prison: a nationwide longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(5):422–30.

Marsden J, Stillwell G, Jones H, Cooper A, Eastwood B, Farrell M, Lowden T, Maddalena N, Metcalfe C, Shaw J, Hickman M. Does exposure to opioid substitution treatment in prison reduce the risk of death after release? a national prospective observational study in England. Addiction. 2017;112(8):1408–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13779. (Epub 2017 Mar 1 PMID: 28160345).

Saloner B, Chang HY, Krawczyk N, Ferris L, Eisenberg M, Richards T, Lemke K, Schneider KE, Baier M, Weiner JP. Predictive modeling of opioid overdose using linked statewide medical and criminal justice data. JAMA Psychiat. 2020;77(11):1155–62. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1689.PMID:32579159;PMCID:PMC7315388.

Kinner SA, Preen DB, Kariminia A, Butler T, Andrews JY, Stoové M, Law M. Counting the cost: estimating the number of deaths among recently released prisoners in Australia. Med J Aust. 2011;195(2):64–8. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03208.x.Erratum.In:MedJAust.2011Aug15;195(4):232. (PMID: 21770872).

Alex B, Weiss DB, Kaba F, Rosner Z, Lee D, Lim S, Venters H, MacDonald R. Death after jail release. J Correct Health Care. 2017;23(1):83–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078345816685311. (Epub 2017 Jan 1 PMID: 28040993).

Andersson L, Håkansson A, Krantz P, Johnson B. Investigating opioid-related fatalities in southern Sweden: contact with care-providing authorities and comparison of substances. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-019-0354-y.PMID:31918732;PMCID:PMC6953255.

Barry LC, Steffens DC, Covinsky KE, Conwell Y, Li Y, Byers AL. Increased risk of suicide attempts and unintended death among those transitioning from prison to community in later life. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(11):1165–74.

Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Lindsay RG, Stern MF. Risk factors for all-cause, overdose and early deaths after release from prison in Washington state. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.029. (Epub 2011 Feb 3 PMID: 21295414).

Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, Stern MF. Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(9):592–600. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00005.PMID:24189594;PMCID:PMC5242316.

Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Yamashita TE, Mueller SR, Baggett TP, Blatchford PJ. Clinical risk factors for death after release from prison in Washington State: a nested case-control study. Addiction. 2016;111(3):499–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13200.PMID:26476210;PMCID:PMC4834273.

Binswanger IA, Nguyen AP, Morenoff JD, Xu S, Harding DJ. The association of criminal justice supervision setting with overdose mortality: a longitudinal cohort study. Addiction. 2020;115(12):2329–38.

Bird SM, Fischbacher CM, Graham L, Fraser A. Impact of opioid substitution therapy for Scotland’s prisoners on drug-related deaths soon after prisoner release. Addiction. 2015;110(10):1617–24.

Bird SM, McAuley A, Perry S, Hunter C. Effectiveness of Scotland’s National Naloxone programme for reducing opioid-related deaths: a before (2006–10) versus after (2011–13) comparison. Addiction. 2016;111(5):883–91.

Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Macmadu A, Marshall BDL, Heise A, Ranapurwala SI, Rich JD, Green TC. Risk of fentanyl-involved overdose among those with past year incarceration: Findings from a recent outbreak in 2014 and 2015. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;1(185):189–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.014. (Epub 2018 Feb 9 PMID: 29459328).

Bukten A, Stavseth MR, Skurtveit S, Tverdal A, Strang J, Clausen T. High risk of overdose death following release from prison: variations in mortality during a 15-year observation period. Addiction. 2017;112(8):1432–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13803. (Epub 2017 Apr 7 PMID: 28319291).

Calcaterra S, Blatchford P, Friedmann PD, Binswanger IA. Psychostimulant-related deaths among former inmates. J Addict Med. 2012;6(2):97–105. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0b013e318239c30a.PMID:22134174;PMCID:PMC3883279.

Degenhardt L, Larney S, Kimber J, Gisev N, Farrell M, Dobbins T, Weatherburn DJ, Gibson A, Mattick R, Butler T, Burns L. The impact of opioid substitution therapy on mortality post-release from prison: retrospective data linkage study. Addiction. 2014;109(8):1306–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12536. (Epub 2014 Apr 14 PMID: 24612249).

Forsyth SJ, Alati R, Ober C, Williams GM, Kinner SA. Striking subgroup differences in substance-related mortality after release from prison. Addiction. 2014;109(10):1676–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12646. (Epub 2014 Jul 2 PMID: 24916078).

Forsyth SJ, Carroll M, Lennox N, Kinner SA. Incidence and risk factors for mortality after release from prison in Australia: a prospective cohort study. Addiction. 2018;113(5):937–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14106. (Epub 2017 Dec 19 PMID: 29154395).

Gan WQ, Kinner SA, Nicholls TL, Xavier CG, Urbanoski K, Greiner L, Buxton JA, Martin RE, McLeod KE, Samji H, Nolan S, Meilleur L, Desai R, Sabeti S, Slaunwhite AK. Risk of overdose-related death for people with a history of incarceration. Addiction. 2021;116(6):1460–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15293. (Epub 2020 Nov 27 PMID: 33047844).

Gjersing L, Jonassen KV, Biong S, Ravndal E, Waal H, Bramness JG, Clausen T. Diversity in causes and characteristics of drug-induced deaths in an urban setting. Scand J Public Health. 2013;41(2):119–25.

Green TC, Clarke J, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Marshall BDL, Alexander-Scott N, Boss R, Rich JD. Postincarceration Fatal Overdoses After Implementing Medications for Addiction Treatment in a Statewide Correctional System. JAMA Psychiat. 2018;75(4):405–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4614.PMID:29450443;PMCID:PMC5875331.

Groot E, Kouyoumdjian FG, Kiefer L, Madadi P, Gross J, Prevost B, Jhirad R, Huyer D, Snowdon V, Persaud N. Drug toxicity deaths after release from incarceration in Ontario, 2006–2013: review of coroner’s cases. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0157512 PMID: 27384044; PMCID: PMC4934911.

Hacker K, Jones LD, Brink L, Wilson A, Cherna M, Dalton E, Hulsey EG. Linking opioid-overdose data to human services and criminal justice data: opportunities for intervention. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(6):658–66.

Hakansson A, Berglund M. All-cause mortality in criminal justice clients with substance use problems–a prospective follow-up study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(3):499–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.014. (Epub 2013 Apr 25 PMID: 23623042).

Kouyoumdjian FG, Kiefer L, Wobeser W, Gonzalez A, Hwang SW. Mortality over 12 years of follow-up in people admitted to provincial custody in Ontario: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2016;4(2):E153–61. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20150098.PMID:27398358;PMCID:PMC4933645.

Larochelle MR, Bernstein R, Bernson D, Land T, Stopka TJ, Rose AJ, Bharel M, Liebschutz JM, Walley AY. Touchpoints - opportunities to predict and prevent opioid overdose: a cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107537 Epub 2019 Sep 3. PMID: 31521956; PMCID: PMC7020606.

Lim S, Seligson AL, Parvez FM, Luther CW, Mavinkurve MP, Binswanger IA, Kerker BD. Risks of drug-related death, suicide, and homicide during the immediate post-release period among people released from New York City jails, 2001–2005. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(6):519–26.

Loeliger KB, Altice FL, Ciarleglio MM, Rich KM, Chandra DK, Gallagher C, Desai MM, Meyer JP. All-cause mortality among people with HIV released from an integrated system of jails and prisons in Connecticut, USA, 2007–14: a retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Hiv. 2018;5(11):E617–28.

Pizzicato LN, Drake R, Domer-Shank R, Johnson CC, Viner KM. Beyond the walls: risk factors for overdose mortality following release from the Philadelphia Department of Prisons. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;1(189):108–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.034. (Epub 2018 Jun 5 PMID: 29908410).

Rosen DL, Kavee AL, Brinkley-Rubinstein L. Postrelease mortality among persons hospitalized during their incarceration. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;45:54–60.

Spittal MJ, Forsyth S, Pirkis J, Alati R, Kinner SA. Suicide in adults released from prison in Queensland, Australia: a cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(10):993–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204295. (Epub 2014 Jul 9 PMID: 25009152).

Spittal MJ, Forsyth S, Borschmann R, Young JT, Kinner SA. Modifiable risk factors for external cause mortality after release from prison: a nested case-control study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;28(2):224–33.

Van Dooren K, Kinner SA, Forsyth S. Risk of death for young ex-prisoners in the year following release from adult prison. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2013;37(4):377–82.

Webb RT, Qin P, Stevens H, Shaw J, Appleby L, Mortensen PS. National study of suicide method in violent criminal offenders. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(2):237–44.

Wortzel HS, Blatchford P, Conner L, Adler LE, Binswanger IA. Risk of death for veterans on release from prison. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2012;40(3):348–54.

Mital S, Wolff J, Carroll JJ. The relationship between incarceration history and overdose in North America: a scoping review of the evidence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;213:108088 Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32498032; PMCID: PMC7683355.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Sci. 2010;5:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

Parmar MK, Strang J, Choo L, Meade AM, Bird SM. Randomized controlled pilot trial of naloxone-on-release to prevent post-prison opioid overdose deaths. Addiction. 2017;112(3):502–15.

Kinner SA, Lennox N, Williams GM, Carroll M, Quinn B, Boyle FM, Alati R. Randomised controlled trial of a service brokerage intervention for ex-prisoners in Australia. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;36(1):198–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2013.07.001. (Epub 2013 Jul 10 PMID: 23850859).

Wang EA, Hong CS, Samuels L, Shavit S, Sanders R, Kushel M. Transitions clinic: creating a community-based model of health care for recently released California prisoners. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(2):171–7.

Parkes T, Price T, Foster R, Trayner KMA, Sumnall HR, Livingston W, Perkins A, Cairns B, Dumbrell J, Nicholls J. “Why would we not want to keep everybody safe?” the views of family members of people who use drugs on the implementation of drug consumption rooms in Scotland. Harm Reduct J. 2022;19(1):99. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-022-00679-5.PMID:36038919;PMCID:PMC9421633.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Richard Fallis, Subject Librarian for the School of Medicine, Dentistry and Biomedical Sciences in Queen’s University Belfast, for assisting in the development of the search terms and search strategy to be used in this scoping review.

CRediT author statement

Janine Cooper: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ifeoma Onyeka: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Chris Cardwell: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. Euan Paterson: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Richard Kirk: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Dermot O'Reilly: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Michael Donnelly: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

This work is funded by a grant awarded to the ADRC NI by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) (grant number ES/W010240/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JAC, DO’R, RK and MD conceived the scoping review idea. JAC and MD developed the scoping review protocol, scoping review title, research questions and methods. JAC and IO piloted the charting form. JAC and IO independently screened all titles and abstracts. Subsequently, JAC and IO independently screened full publications, any discrepancies were resolved between JAC and MD. The charting form was retested by JAC and EP as part of this review. JAC independently extracted information from all included publications. EP independently extracted information from a proportion of the included publications (n = 14). JAC and MD met weekly and discussed the studies in the review. JAC and CC conducted and interpreted the statistical analysis for pooled SMRs. JAC drafted the manuscript. MD edited the drafts of the manuscript. All co-authors reviewed the manuscript and have given final approval for publication. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cooper, J.A., Onyeka, I., Cardwell, C. et al. Record linkage studies of drug-related deaths among adults who were released from prison to the community: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 23, 826 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15673-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15673-0