Abstract

Introduction

Suicide is a major public health problem in Pakistan, accounting to approximately 19,331 deaths every year. Many are due to consumption of acutely toxic pesticides; however, there is a lack of national suicide data, limiting knowledge and potential for intervention. In this paper, we aimed to review the literature on pesticide self-poisoning in Pakistan to identify the most problematic pesticides in relation to national pesticide regulations.

Methods

Information on the currently registered and banned pesticides was obtained from Ministry of National Food Security and Research while data on pesticide import and use was extracted from FAOSTAT. We searched the following sources for articles and research papers on poisoning in Pakistan: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), Google Scholar, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Excerpta Medica (EMBASE), National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE (PUBMED), PS102YCHINFO and Pakmedinet.com using the search terms ‘self-poisoning’, ‘deliberate self-harm’, ‘suicide’, ‘methods and means of suicide’, ‘organophosphate’, ‘wheat pill’, ‘aluminium phosphide’, ‘acute poisoning’, OR ‘pesticides’, AND ‘Pakistan’.

Results

As of May 2021, 382 pesticide active ingredients (substances) were registered in Pakistan, of which five were WHO hazard class Ia (extremely hazardous) and 17 WHO hazard class Ib (highly hazardous). Twenty-six pesticides, four formulations, and seven non-registered pesticides had been banned, of which two were WHO class Ia and five Ib. We identified 106 hospital-level studies of poisoning conducted in Pakistan, of which 23 did not mention self-poisoning cases and one reported no suicidal poisoning cases. We found no community or forensic medicine studies. Of 52,323 poisoning cases identified in these papers, 24,546 [47%] were due to pesticides. The most commonly identified pesticide classes were organophosphorus (OP) insecticides (13,816 cases, 56%) and the fumigant aluminium phosphide (3 g 56% tablets, often termed ‘wheat pills’; 686 cases, 2.7%). Few studies identified the particular pesticides involved or the resulting case fatality.

Conclusion

We found pesticide poisoning to be a major cause of poisoning in Pakistan, with OP insecticides and the fumigant aluminium phosphide the main pesticides identified. Withdrawal of Class I pesticides (as proposed to occur nationally in 2022) and high concentration aluminium phosphide tablets should rapidly reduce suicidal deaths by reducing the case fatality for low-intention poisoning cases. National cause of death data and forensic toxicology laboratory data identifying the pesticides responsible for deaths will be important to assess impacts of the proposed national ban.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Highly hazardous pesticides (HHPs) cause harmful acute or chronic health effects on people and livestock [1, 2]. They harm reproductive and neurological systems [3,4,5,6], and can lead to immunological, genotoxic, endocrine disrupting and carcinogenic conditions [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Acutely toxic HHPs have a high case fatality after consumption compared to other domestically available poisons such as overdoses of sedative or analgesic medicines [13]. At least fourteen million people have died from pesticide suicides since the Green Revolution brought these toxic chemicals into rural communities in the 1950/60s [14]. However, self-poisoning is often an impulsive decision, taken after less than 30 minutes of suicidal thoughts [15]. If a person survives the act, she/he can receive support from family and peers, reducing the risk of a repeat attempt [13,14,15,16,17]. If acutely toxic HHPs are made less available in these communities, a person will consume a less toxic poison, making the attempt less dangerous and increasing the chance of survival [15].

The issues of pesticide poisoning and suicide are not well described for Pakistan. National health vital statistics on suicide or poisoning are not collected, which hinders understanding of the gravity of the problem for policy level solutions. The WHO (2019) reports an estimate for the country of ~ 19,331[18] suicides per year. However, they are under-reported due to social stigma and being a criminal offence under Sect. 325 of the Pakistan Penal Code [PPC] [19, 20] until 2022. Pakistan’s progressive step in December 2022 to decriminalize suicide should improve suicide reporting. Taking into consideration the unreported suicides, it is likely that more than 19,331 suicides occur every year in Pakistan, with poisoning, firearms, and hanging being the top three means of suicide [19, 21, 22]. Pesticides are likely to be the most important means of suicide by poisoning.

In 2019, the Pakistan government’s Department of Plant Protection (Box 1) decided to phase out the use of WHO hazard class Ia (extremely hazardous [23]) and class Ib (highly hazardous) pesticides by 2022, subject to availability of alternatives [24]. This accords with WHO advice on the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of pesticide bans for suicide prevention [25, 26]. However, it is not clear whether the pesticides listed for bans are the pesticides involved in most self-harm deaths. We therefore undertook a systematic review of the issue of pesticide poisoning and suicides in Pakistan in light of the planned pesticide regulation to identify the most important pesticides [27].

Text box 1. Pesticide regulation in Pakistan | |

|---|---|

Since the formation of Pakistan in 1947, the distribution and procurement of pesticides has been administered directly by the federal government [28]. Currently, the Department of Plant Protection, under the Ministry of National Food Security and Research, monitors the import and standardization of pesticides and implements pesticide regulation. Chemical pesticides were first used in Pakistan in 1950 to deal with locusts [12]. Until 1971, pesticides were freely distributed to the farmers. The Agricultural Pesticides Ordinance of 1971 and Agricultural Pesticides Rules of 1973 were then implemented to regulate the import, manufacture, formulation and sale of registered pesticides [28, 29]. In 1980, Pakistan announced a liberalisation policy that shifted the distribution, sales and import of pesticides into the hands of the private sector [7, 30]. Essentially, liberalization facilitated the import of pesticides, complimented by a low-price structure, increasing the consumption of pesticides five-fold in just one year [7]. However, in 1983, the Pakistan Environmental Protection Ordinance included pesticide regulations due to concerns about environmental degradation [31]. The government then banned 22 pesticides from 1989 to 1993 (Table 1). A further four acutely toxic HHPs associated with many deaths in South Asia were banned between 2001 and 2012 (Table 1). However, a lack of proper enforcement of pesticide regulations [32] has enabled the continued use of some banned pesticides, such as DDT and ethylene dichloride [27, 33,34,35]. Pakistan has developed ‘Good Pesticide Application Practices’ for ground operations following FAO and WHO guidelines due to concerns about pesticide mishandling, misuse, and overuse [36]. It focusses on correct application practice, safety measures while applying, protecting the health of operators, transport, and storage management [36]. Pakistan has signed the Stockholm and Rotterdam Conventions. The Department of Plant Protection regularly reviews updated lists of banned chemicals from the conventions and, after approval from the Ministry of National Food Security and Research, places a ban on such chemicals. |

Methods

Pesticide regulation

Information on pesticide regulation was obtained from the 2018 Pesticide Handbook published by the Pakistan Agricultural Research Council, Ministry of National Food Security and Research [36].

Pesticide consumption

Data on pesticide consumption and national level per hectare pesticide consumption in Pakistan were obtained from FAOSTAT. However, Pakistan has not reported pesticide use per hectare to the FAO since 2013; compound specific consumption data are not available.

Pesticide poisoning and suicides

The review was conducted using Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005)[37] framework, that described five stages: identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data and summarizing and reporting the results. The methods of this review described in the light of above stages are as follows:-

Stage 1: The review was conducted to identify the poisoning cases as a method of suicide or self-harm in Pakistan.

Stage 2: In order to identify and include relevant studies, we used combination of key terms including ‘self-poisoning’, ‘deliberate self-harm’, ‘suicide’, ‘methods and means of suicide’, ‘organophosphate’, ‘wheat pill’, ‘aluminium phosphide’, ‘acute poisoning’, or ‘pesticides’, AND ‘Pakistan’. We searched different electronic databases including Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), Google Scholar, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Excerpta Medica (EMBASE), National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE (PUBMED), and PSYCHINFO. Pakmedinet.com, a Pakistani medical literature search website, was also searched for relevant literature. These databases were searched from their beginning until June 2021. In addition, an ancestry approach was taken in which the reference lists of retrieved articles were hand checked for relevant references.

The selected studies were assessed against the following inclusion criteria:

-

(i)

Studies conducted on suicide or self-harm;

-

(ii)

Studies mentioned poisoning as a method of suicide or self-harm;

-

(iii)

Suicidal behaviour in both genders and across all ages;

-

(iv)

English as the publication language;

-

(v)

Studies used retrospective, cross-sectional, or prospective study designs.

-

(vi)

Studies conducted within the geographical boundaries of Pakistan.

On the other hand, any study that did not fulfill the inclusion criteria and those conducted on Pakistani people residing outside the country were excluded from this review.

Stage 3: A two stage study selection process was followed. In the initial phase, titles and abstracts of the study were screened. In the second stage, full text of the articles was retrieved after applying the eligibility criteria.

Stage 4: Based on literature review and study objectives, the data extraction form was developed in consultation with the subject expert. This form included information on study design, time of study, year, place of study, number of suicidal cases, number of poisoning cases, type of poisoning, age, gender, outcome, and mortality due to suicidal poisoning. The data was entered in Microsoft Excel. The form was pilot tested, and modifications were made accordingly.

Stage 5: Information on pesticide class, number of pesticides poisonings, number of suicidal pesticides poisoning, gender, age and mortality due to suicidal poisoning were the basis of analysis. Throughout the process, team meetings were held, and each step was discussed.

Statistical analysis

Simple descriptive statistics were used to analyse the data.

Results

Pesticides registered in Pakistan

As of April 2022, 382 pesticide active ingredients (substances) were registered in Pakistan of which five are WHO hazard class Ia (extremely hazardous), 17 class Ib (highly hazardous), and 36 class II (moderately hazardous) (Table 2; online supplementary table) [Table S1- S10 series].

Twenty-six pesticides, four formulations, and seven non-registered pesticides are currently banned in Pakistan (Table 1). Four of these pesticides are WHO hazard class Ia, four class Ib, and five class II; two were classified as unlikely to present acute hazard. The Department of Plant Protection announced in 2019 that all the currently registered WHO class I pesticides (five class Ia, 17 class Ib) would be withdrawn in 2022 [24].

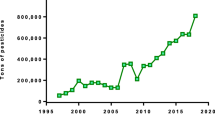

Use of pesticides in Pakistan

The annual consumption of pesticides in Pakistan is 130,000 metric tonnes, of which 90% is applied on cotton, rice, vegetables and fruits [38]; China is the source of 91% pesticides in Pakistan [39]. The pesticide market was valued at USD 220 million in 2019 and is forecast to reach USD 349.5 million by 2025 [40]. Use of biopesticides is low due to lack of expertise in manufacture and use [39]. The Pakistan pesticide sector mainly consists of 272 small scale importers that sell the products through dealers to end users [39].

Pakistan uses 69% of its pesticides on cotton [7], so any change in the area or technology of cotton production impacts national consumption of pesticides[41]. Thus, the decreasing pesticide use in Pakistan is associated with a reducing area of cotton agriculture and introduction of Bt. cotton in 2002 [27]. Relative to neighbouring countries, Pakistan uses a very low quantity. In 2012, China, India and Pakistan used 13.35 kg/hectare, 0.31 kg/hectare, and 0.03 kg/hectare pesticides on arable land, respectively. Pesticide consumption data post 2013 is not available (due to lack of reporting from Pakistan).

Pesticide self-poisoning in Pakistan

We identified a total of 106 hospital studies [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146], starting from 1977, from across Pakistan, of which 83 mentioned the intention of poisoning. We did not identify any community level studies or forensic medicine studies reporting fatal poisoning cases.

The papers reported a total of 53,323 cases of poisoning, of which 24,546 [46.0%] were due to pesticides [Fig. 1]. OP insecticides were responsible for 13,816 (56.2%) of the total pesticide poisoning cases; unfortunately, no data were presented on the identity of the most important OP insecticides for poisoning or deaths. Two studies mentioned malathion and parathion as being commonly used OP pesticides [91, 134]; remarkably just two studies reported pesticide specific poisoning data: in two case series, 48 (23%) cases were due to dichlorvos [136] and 59 (46%) cases due to paraquat [44]. The fumigant aluminium phosphide - as a 3 g 56% tablet - was identified as being responsible for 686 (3%) poisoning cases. OP insecticide self-poisoning was first reported in 1977 [147] while aluminium phosphide self-poisoning was first reported in 1997 [126]. A single paper, reporting 11925 cases admitted to 3 hospitals in Karachi after self-poisoning in 2006-11, noted that household pyrethroid insecticide mixtures were responsible for 62% of cases [68]. Among all pesticide poisoning papers, 79% of cases were due to self-poisoning [Fig. 2].

The data did not allow the number of deaths from pesticide poisoning to be calculated, because deaths were often not reported and, if reported, pesticide deaths were usually mixed in with other poisons. However, estimates could be generated from studies that reported only pesticide poisoning and the number of deaths. Twenty-one studies of OP insecticide poisoning reported 376/3504 deaths (13% case fatality) while six studies of aluminium phosphide poisoning reported 163/262 deaths (62% case fatality).

Data on gender were available in 74 papers reporting pesticide poisoning only. In these studies, 44% and 49% of cases were male and female (7% unknown), respectively. The 25 studies that reported only OP poisoning and gender data included 44% males and 48% female. Similarly, the seven studies that reported only aluminium phosphide poisoning included 47% males and 52% females. There were no data on the number of deaths by gender in these studies.

Other types of poisoning identified from our literature review included overdose of medicines, drugs, and household compounds. Of note, paraphenylenediamine (PPD) hair dye was reported in 20 publications and responsible for many self-poisoning cases and some deaths [49, 50, 62, 69, 70, 75, 76, 79, 80, 86, 88, 92, 104, 105, 122, 124, 129, 142]. There was a more marked female/male imbalance in these cases (2862 women vs. 1176 men).

Discussion

Our systematic literature review found the continued use of acutely toxic HHPs in Pakistani agriculture and the importance of OP insecticides and aluminium phosphide tablets for self-poisoning in Pakistan. Unfortunately, there was a remarkable lack of data on the number of deaths specific to pesticide poisoning, gender, and identity of pesticides responsible for most deaths. Experience from other countries [148, 149] suggest that acutely toxic OP insecticides and aluminium phosphide are likely to be responsible for many deaths.

OP insecticides inhibit the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE) resulting in accumulation of acetylcholine and overstimulation of nervous system receptors [2, 150, 151]. Deaths occur from respiratory arrest, particularly if patients cannot be rapidly and safely transferred to hospital [150]. A Karachi-based hospital study showed that 46.1% of the 2,546 admitted poisoning cases were due to OP insecticides, with the highest case fatality of any poison (3.6%)[46]. This is consistent with their wide use across South Asia for agriculture and hence for self-poisoning [148]. However, the urban location of this hospital and relatively low case fatality [152, 153] suggest that many of the patients admitted to this hospital are ‘survivors’, with most severely poisoned patients not surviving to arrive at this specialist unit or being treated in rural district hospitals (not this specialist centre).

Aluminium phosphide or ‘wheat pills’ are widely used as a fumigant and rodenticide for stored rice and wheat, the major crops grown in Pakistan. It is extremely toxic, releasing phosphine gas following exposure to moisture (including exposure to air or following ingestion) [154]. Case fatality amongst those who ingest aluminium phosphide tablets is greater than 50% despite treatment [155,156,157,158,159]. Wheat pill poisoning is common in north Pakistani wheat-growing areas such as Peshawar [48], Lahore [109], Rawalpindi and Sahiwal [145], while such poisonings have not been noted in the southern Sindh region where wheat is not a key crop [21], showing again the importance of agent availability for self-poisoning. Similarly, aluminium phosphide tablets are a major problem in north India but not the south where they are little used in agriculture [156].

Many less toxic pesticides, other than OP insecticides and aluminium phosphide, are used in agriculture and thus available for self-harm in rural Asia. Unfortunately the literature available from Pakistan does not allow these pesticides to be identified, as has been done for example in Sri Lanka [160]. Poisoning with most of these less toxic pesticides can be successfully treated as long as patients do not aspirate their stomach contents [150]. Deaths are much less common after self-poisoning with these pesticides [153], emphasising the importance of banning acutely toxic HHPs to reduce pesticide poisoning deaths by reducing the case fatality [161, 162].

In 2019, the Pakistan government proposed to ban all 22 WHO class Ia and Ib hazardous pesticides still in agricultural use by 2022, if alternatives could be identified [24]. Such bans of acutely toxic HHPs should reduce deaths from suicidal and occupational pesticide poisoning [163]. However, since aluminium phosphide has not been classified by the WHO [23], such a regulation will not remove this pesticide, which is defined as highly hazardous by the FAO/WHO Joint Meeting on Pesticide Management (JMPM)’s criterion 8 [2] and kills many young people in Pakistan [64, 66, 78, 98, 109]. Replacement of the 3 g 56% tablets with a low concentration granular formulation should reduce deaths, as has been seen in India [164, 165] and recently implemented in Nepal [166, 167].

Pesticides are used in agriculture to prevent pest attacks and protect crops. Pest and locust attacks are common in Pakistan, so the use of pesticides is considered important for agricultural productivity [168]. However, Pakistan’s neighbouring countries, Sri Lanka [169] Bangladesh [170] and Nepal [167], have implemented similar bans without affecting their agricultural productivity by introducing suitable safer alternatives [171]. Pakistan could benefit from the experiences of these South Asian neighbours.

Accessibility to highly lethal means for suicide is a key factor for determining suicide rates. For example, suicides by using guns is common in gun-carrying nations [172, 173], carbon monoxide self-poisoning has become common in East Asian countries where charcoal is available over the counter [174, 175], and drowning is specific to nations like Netherlands with many bodies of water [176] [177]. Two recent review articles on suicide in Pakistan [18][20] show poisoning to be the second most common mode of suicides [19] and the agents to be specific to regions where they are easily accessible [21]. They review the different methods of self-harm [19] and compare the incidence of suicides in rural and urban areas of Pakistan [21]. While OP insecticide poisoning was common in South Punjab and central Sindh, aluminium phosphide poisoning was higher in North Punjab [21]. Paraphenylenediamine was a commonly used agent in South Punjab and household chemical agents like rat poison were commonly used in in urban areas [21].

Self-poisoning is most common amongst individuals below the age of 30 [178] and females [21] [Fig. 3], while the case fatality is highest amongst males. Mental health awareness campaigns, provision of resources and staff training for prompt treatment of poisoning cases, establishment of a central data collection system to diagnose and investigate suicides, and stricter pesticide regulations are key recommendations of both reviews [21, 178].

There are issues with data collection for poisoning and suicide in Pakistan. Poisoning cases, including pesticide self-poisoning cases, are recorded under the broad category of injuries in Pakistan by emergency departments (ED) of hospitals and/or the police. There is a difference in the number and type of cases reported by both sources [20]. Violent or fatal cases are usually reported by the police while injury cases or self-harm are more reported by the EDs [20]. However, there is no centralized system- either at provincial or national levels- to collect suicidal or injury data, resulting in poor quality data for government policy decisions.

We found more female pesticide poisoning cases in the literature than male cases, consistent with data from other countries. However, despite the lack of high-quality data, more men than women are believed to die from pesticide poisoning [21]. More research is required to understand the true rates of self-harm by gender in Pakistan and whether there any gender-specific reasons for self-harm exist.

None of the cited papers differentiated between urban and rural cases. As all the studies were hospital based, it is likely that many cases were derived from urban areas, with cases from rural areas being under-represented. Information on the use of agricultural pesticides in self-poisoning is likely limited compared to insecticides that are available in urban areas.

Limitations

Lack of official national data on suicides by means (and poison) restricted our research to published poisoning studies. We were able to find the most common pesticide classes associated with fatal self-poisoning, based on our review of 106 hospital studies. Unfortunately, these studies do not identify the specific pesticides that caused lethal poisoning (unless all reported poisoning cases were due to a single agent). Identification of the type of compound consumed by an individual at hospital level is important to understand the chemicals responsible and allow evidence-based policy decisions. We were unable to find any community or forensic medicine studies that might have provided some information on the number of people who died before hospital presentation, or died in different level hospitals, or the compounds involved.

The Pakistan government has previously banned pesticides due to their detrimental impact on human and environmental health. However, the lack of national monitoring and data collection on suicides make it difficult to measure the impact of these bans.

Conclusion

OP insecticides and aluminum phosphide fumigant tablets are the two most important pesticides used in self-poisoning and general poisoning cases in Pakistan. The proposed 2022 ban on HHPs would legally restrict the use of the most toxic OP insecticides, but not the use of high concentration aluminium phosphide tablets. Hence, Pakistan needs to devise an exclusive strategy for eliminating the risk of aluminium phosphide tablets or include it in the list of bans. Most pesticide poisoning cases are impulsive decisions, a response to acute stress [164, 179]. Removal of acutely toxic HHPs from agriculture will allow the self-harm impulse to pass without exposure to a lethal means, increasing the chance of survival [180, 181] as has clearly been shown in Sri Lanka [171]. There is an urgent need to set up effective data collection for suicide and poisoning in Pakistan for policy purposes.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. We conducted a systematic review of self-poisoning studies in Pakistan from 1977. Our data sources and research methods are described in line 149 under the title of pesticide poisoning and suicides. All authors declare no competing interest.

References

World Health O, Food. Agriculture Organization of the United N: detoxifying agriculture and health from highly hazardous pesticides: a call for action. Rome: Italy; 2019.

FAO.: International code of conduct for pesticide management: Guidelines on Highly Hazardous Pesticides 2016.

Cha ES, Chang S-S, Gunnell D, Eddleston M, Khang Y-H, Lee WJ. Impact of paraquat regulation on suicide in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(2):470–9.

Damalas CA, Khan M. Pesticide use in vegetable crops in Pakistan: Insights through an ordered probit model (Retraction of pg 59, 2017). Crop protection 2020, 131.

Who. Preventing suicide: A global imperative. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

Carroll R, Metcalfe C, Gunnell D. Hospital presenting self-harm and risk of fatal and non- fatal repetition: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e89944–4.

Muhammad Imran Khan MAS, Sardar Alam HN, Arif NK, Niazi M, Azam I, Ashraf. Rashad Qadri, Safdar Bashir: use, contamination and exposure of Pesticides in Pakistan: a review. Pakistan J Agricultural Sci. 2020;57(1):131–49.

Ejaz S, Akram W, Lim CW, Lee JJ, Hussain I. Endocrine disrupting pesticides: a leading cause of cancer among rural people in Pakistan. Exp Oncol. 2004;26(2):98–105.

Street ME, Bernasconi S. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals in human fetal growth. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4):1430.

Tang Z-R, Xu X-L, Deng S-L, Lian Z-X, Yu K. Oestrogenic endocrine disruptors in the placenta and the fetus. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4):1519.

Ali N, Khan S, Khan MA, Waqas M, Yao H. Endocrine disrupting pesticides in soil and their health risk through ingestion of vegetables grown in Pakistan. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019;26(9):8808–20.

Zaheer Iqbal KZ. Abrar Ahrnad,: Pesticide abuse in Pakistan and associated human health and environmental risks. Pakistan J Agricultural Sci. 1997;34:1–4.

Gunnell D, Eddleston M. Suicide by intentional ingestion of pesticides: a continuing tragedy in developing countries (vol 32, pg 902, 2003). Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33(4):920–0.

Boedeker W, Watts M, Clausing P, Marquez E. The global distribution of acute unintentional pesticide poisoning: estimations based on a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1875–1819.

Eddleston M. Preventing suicide through pesticide regulation. 2020.

Mew EJ, Padmanathan P, Konradsen F, Eddleston M, Chang S-S, Phillips MR, Gunnell D. The global burden of fatal self-poisoning with pesticides 2006-15: systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:93–104.

Clarke RV, Lester D. Suicide: Closing the exits: transaction publishers; 2013.

Organization WH. Suicide Worldwide in 2019. 2021.

Shekhani SS, Perveen S, Hashmi D-e-S, Akbar K, Bachani S, Khan MM. Suicide and deliberate self-harm in Pakistan: a scoping review. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):44–4.

Farooq U, Majeed M, Bhatti JA, Khan JS, Razzak JA, Khan MM. Differences in reporting of violence and deliberate self harm related injuries to health and police authorities, Rawalpindi, Pakistan. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(2):e9373–3.

Safdar M, Afzal KI, Smith Z, Ali F, Zarif P, Baig ZF. Suicide by poisoning in Pakistan: review of regional trends, toxicity and management of commonly used agents in the past three decades. BJPsych open. 2021;7(4):e114–4.

Abdullah M, Khalily MT, Ahmad I, Hallahan B. Psychological autopsy review on mental health crises and suicide among youth in Pakistan. Asia-Pacific psychiatry. 2018;10(4):e12338. -n/a.

World Health Organization. The WHO recommended classification of pesticides by hazard and guidelines to classification: 2019. Geneva: WHO; 2020.

Plantwise.: https://blog.plantwise.org/2019/10/23/registration-of-red-list-chemicals-halted-in-pakistan-thanks-to-plantwise/. 2019.

Lee YY, Chisholm D, Eddleston M, Gunnell D, Fleischmann A, Konradsen F, Bertram MY, Mihalopoulos C, Brown R, Santomauro DF, et al. The cost-effectiveness of banning highly hazardous pesticides to prevent suicides due to pesticide self-ingestion across 14 countries: an economic modelling study. The Lancet global health. 2021;9(3):e291–e300.

WHO.: Preventing suicide: A resource for pesticide registrars and regulators. 2019.

Tariq MI, Afzal S, Hussain I, Sultana N. Pesticides exposure in Pakistan: a review. Environ Int. 2007;33(8):1107–22.

The agricultural pesticide technical advisory commitee P.: The Agricultural Pesticide Ordinance. 1971.

Agricultural Pesticides Technical Advisory Committee P.: Agricultural pesticides rules 1973.

Jabbar A, Mallick S. Pesticides and Environment Situation in Pakistan. In.: Sustainable Development Policy Institute; 1994.

Pakistan So.: Pakistan Environmental Protection Act (PEPA). 1997.

Ahmad A, Shahid M, Khalid S, Zaffar H, Naqvi T, Pervez A, Bilal M, Ali MA, Abbas G, Nasim W. Residues of endosulfan in cotton growing area of Vehari, Pakistan: an assessment of knowledge and awareness of pesticide use and health risks. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019;26(20):20079–91.

Mehmood Y, Arshad M, Mahmood N, Kächele H, Kong R. Occupational hazards, health costs, and pesticide handling practices among vegetable growers in Pakistan. Environ Res. 2021;200:111340.

Saeed MF, Shaheen M, Ahmad I, Zakir A, Nadeem M, Chishti AA, Shahid M, Bakhsh K, Damalas CA. Pesticide exposure in the local community of Vehari District in Pakistan: an assessment of knowledge and residues in human blood. Sci Total Environ. 2017;587:137–44.

Mughal F. Environmental impact of pesticide overuse. In.: Dawn; 2018.

Council, PAr. A Handbook for agricultural extension agents. 2018.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Inam-ul-Haq M, Hyder S, Nisa T, Bibi S, Ismail S, Ibrahim Tahir M. Overview of Biopesticides in Pakistan. In. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2019. pp. 255–68.

Limited) PPCRA. Pesticides: an overview. February; 2021.

Intelligence M. INSECTICIDES MARKET - GROWTH, TRENDS, COVID-19 IMPACT, AND FORECASTS (2021–2026). 2021.

Zadran NKJ, Ibrar A et al. Sociodemographic and Clinical Features in Patients Presented With Accidental and Deliberate Self-Poisoning: A Comparative Study from Lady Reading Hospital Medical Teaching Institution, Peshawar,Pakistan. Cureus2020,12.

Ali SMKI, Saeed A, Hussain Z. Five years audit for presence of toxic agents/drug of abuse at autopsy.JCPSP 2003(13(9):):519–521.

Ali PAA, Bashir B, Jabeen R, Haroon H, Makki K. Clinical pattern and outcome of organophosphorus poisoning.J Liaq Uni Med Health Sci2012.

Ali ZAM, Muhammad R, Rahim A, Rahman SKU, Ullah N, et al. Outcome and predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients presenting with acute poisoning to a teaching hospital. J Postgrad Med Inst. 2018;32:155–61.

Ali MKV, Ahmed S, Iram H, Ahmed S, Sattar RA. Mortality among Organophosphate Poisoning Patients presenting with low Glasgow Coma Scale score at a Tertiary Care Hospital. Prof Med J. 2020;27:2187–92.

Amir A, Haleem F, Mahesar G, Abdul Sattar R, Qureshi T, Syed JG, Ali Khan M. Epidemiological, poisoning characteristics and treatment outcomes of patients admitted to the National Poisoning Control Centre at Karachi, Pakistan: a six Month Analysis. Cureus. 2019;11(11):e6229–9.

Amir ARA, Qureshi T, et al. Organophosphate Poisoning: demographics, severity scores and outcomes from National Poisoning Control Centre, Karachi. Cureus May. 2020;12(5):e8371.

Ansari RZ, Aamir Y, Tanoli AA, Yadain SM, Khalil ZH, Yousaf M. Acute Poisoning Cases in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Peshawar.International Journal of Pathology(2018).:73–77.

Ansari RZKA, Yadain SM, Shafi S, Haq AU, Khalil ZH. Incidence of paraphenylene-diamine (PPD) poisoning in three district headquarters hospitals of Pakistan. 2019, 31:544–547.

Arif U, Hafeez MR, et al. Examine the frequency of Acute Renal failure in patients with paraphenylene diamine poisoning. P J M H S. 2020;14:555–7.

Asghar SP, Ather N, Farooq M, Sidra S, Asghar S, Ijaz A. Presentation and management of organophosphate poisoning in an intensive care unit. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2014;64:134–8.

Ather NA, Ara J, Khan EA, Sattar RA, Durrani R. Acute organophosphate insecticide poisoning. J Surg Pak. 2008;13(2):71–4.

Basher FKA, Rajesh NB, Shoaib MA, Ghauri MI. Gender Differences in Risk Factors and Patterns Contributing Towards Deliberate Self-Poisoning. 2015, 1(23 – 8).

Bashir F, Ara J, Kumar S. Deliberate self-poisoning at National Poisoning Control Centre. J Liaquat Uni Med Health Sci. 2014;13:3–8.

Bhatti NKD, Saleem S, Ijaz A, Aamir M. Frequency of drug poisoning in adults at tertiary care hospital, Wah Cantt. Pak J Pathol. 2015;26:27–34.

Bilal M, Khan Y, Ali S, Naeem A. The pattern of organophosphorus poisoning and it’s short term outcomes in various socioeconomic groups. KJMS. 2014;7(1):11.

Bunggush RAAT. Preliminary survey for pesticide poisoning in Pakistan.Pak J Biol Sci2003(3:1976–8.).

Durrani ASO, Sabir A, Faisal M. Types of Poisoning Agents used in patients admitted to Medical Department of Holy Family Hospital Rawalpindi (Pakistan) from 2011 to 2015. Asia Pac J Maed Toxicol. 2017;6:50–4.

Faiz MSMS, Memon AQ. Acute and late complications of organophosphate poisoning.J Coll Physicians Surg Pak2011:288–290.

Farooqi ANTS, Asad F, Abid F, Tariq O. Epidemiological profile of suicidal poisoning at Abbasi Shaheed hospital. Ann Abbasi Shaheed Hosp Med & Dental Coll 2004. 2004;9:502–5.

Haider SHI. Deliberate self-poisoning (unemployment and debt).JPak Med Sci2002(18):122–125.

Haider SHSA, Salman Z, Waris S, Bandesha Y. Anaesth Pain & Intensive Care: Paraphenylenediamine poisoning: clinical presentations and outcomes. 2018(1):43–47.

Hashmi MAM, Ullah K et al. Clinico-epidemiological Characteristics of Corrosive Ingestion: A Cross-sectional Study at a Tertiary Care Hospital of Multan, South-Punjab Pakistan. Cureus May 29, 2018.

Hassan A. Wheat Pill Poisoning: Clinical Manifestation and its Outcome.Journal Of Rawalpindi Medical College2014(18(1)):49–51.

Aziza Mohammed Hussain STS. Organophosphorus Insecticide Poisoning:management in surgical care unit. JCPSP. 2005;15(2):100–2.

Iftikhar RTK, Saeed F, Khan MB, Babar NF. Wheat pill: clinical characteristics and outcome.Pak Armed Forces Med J2011(3):350–353.

Imran S, Awan EA, Memon MIS, Memon A. Frequency and outcomes of Organophosphate Poisoning at Tertiary Care Hospital in Nawabshah. J Liaquat Uni Med Health Sc. 2017;16(2):118–20.

Imtiaz F, Ali M, Ali L. (2015: Prevalence of chemical poisoning for suicidal attempts in Karachi, Pakistan. Emerg Med (Los Angel) (247).

Javed Iqbal MH, Abid, Hussain. Muhammad Bilal Ghafoor: Paraphylene Diamine/Kala Pathar poisoning; to study the demographic profile, clinical manifestations and outcome of paraphylene diamine/kala pathar poisoning at Sheikh Zayed hospital Rahim Yar Khan. TPMJ 2019, 26.05.3484.

Ishtiaq R, Shafiq S, Imran A, Masroor Ali Q, Khan R, Tariq H, Ishtiaq D. Frequency of Acute Hepatitis following Acute Paraphenylene Diamine Intoxication. Curēus (Palo Alto CA). 2017;9(4):e1186–6.

Jamil HKA, Akhtar S, Sultana N. Patients with acute poisoning seen in the department of intensive care-Jinnah postgraduate medical Centre, Karachi.J Pak Med Assoc1977(27:358–60.).

H J: Acute poisoning: a review of 1900 cases.J Pak Med Assoc1990(40):131–133.

Jan AKM, Khan MTH, Khan MTM et al. Poisons Implicated in Homicidal, Suicidal and Accidental Cases in North-West Pakistan.J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad2016:308–311.

Javed AWF, Ahmed S, Rahman AS, Jamal Q, Hussain T. Different patterns of ecg in organophosphate poisoning and efffect on mortality. Pak Heart J 2016; 2016: 121–125.

Kanhar AAMW, Aamer N, Sial BA, Sahito A, Pervez SA. Frequency of acute renal failure in blackstone poisoning. Prof Med J. 2020;27:1285–90.

Kazi MASA, Samad A, Bibi I, Khan M. Kala pathar (Paraphenylene Diamine) poisoning: an ICU based observational study at Hyderabad, Pakistan. Indo Am J P Sci. 2018;5:9334–7.

Khalid H, Khalid T, Arif S. Deaths due to poisoning in Lahore: a retrospective study. Pakistan Postgrad Med J. 2018;29(3):104–6.

Khan M, Khurram M, Raza S. Gender based differences in patients of poisoning managed at a medical unit. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019;69(7):1025–8.

Khan MA, Akram S, Shah HBU, Hamdani SAM, Khan M. Epidemic of kala pathar (paraphenylene diamine) poisoning: an emerging threat in southern Punjab. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2018;28:44–7.

Khan NKH, Khan N, Ahmad I, Shah F, Rahman AU, Mahsud I. Clinical presentation and outcome of patients with paraphenylenediamine (kala-pathar) poisoning. Gomal J Med Sci. 2015;14:3–6.

Khan MMRH. Benzodiazepine self-poisoning in Pakistan: implications for prevention and harm reduction.J Pak Med Assoc1998(48):293–295.

Khan MN, Hanif S. Deliberate self harm due to organophosphates. JPIMS 2003(14(2)):784–789.

Intentional and unintentional pesticide poisoning in Pakistan: a pilot study using Emergency Departments surveillance project. BMC emergency medicine 15 (S2) 2015

Trends of acute poisoning: 22 years experience from a tertiary care hospital in Karachi,Pakistan.Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 2016) 66:1237–1242.

Khan RA, Rizvi SL, Ali MA. Pattern of intoxication in poisoning cases; reported in casualty of Bahawal Victoria Hospital. Bahawalpur.Med J2003(10):236–238.

Khaskheli MSSS, Meraj M, Raza H, Aslam I. Anaesth Pain & Intensive Care Paraphenylenediamine poisoning: clinical features, complications and outcome in a tertiary care. 2018, 22:343–347.

Khoso FH, Panhwar F, Arain MI, Dayo A, Ghoto MA. Assessment of various types of poisoning cases reported in district hospital Badin, Sindh province, Pakistan.Rawal Medical Journal, 2020(2):273–277.

Khuhro BAKM, Shaikh AA. Paraphenylene diamine poisoning: Our experience at PMC Hospital Nawabshah.Anaesth Pain & Intensive Care. 2012(3):243–246.

Khurram M, Mahmood N. x: Short communication-deliberate self-poisoning: experience at a medical unit.Pakistan Medical Association2008(58):455–457.

Khurram M, Mahmood N, Ikram N. Unintentional poisoning: experience at a medical unit.Journal of Rawalpindi Medical College, 2010, (1):46–48.

Lakhair ALSM, Kumar S, Zafarullah, Bano R, Maheshwari BK. Frequency of Various Clinical and Electrocardiac manifestation in Patients with Acute Organophosphorous Compound (OPC) Poisoning. JLUMHS 2012(34).

Lohano AK, Yousfani AH, Malik AA, Arain KH. Hair dye crucial threat to paraphenylenediamine poisoning and its mortality rate associated with laryngeal edema; a cross sectional study.Rawal Med J2017(1):60–63.

Maqbool F. Organophosphate Poisoning–Clinical Profile.Journal of Rawalpindi Medical College, 2015(1):15–19.

SHAHEEN MAQSOODM, M. Z. B. M. A., ZAFAR M. Pattern of Aluminium Phosphide poisoning and autopsy Findingsat KEMU Lahore. J Fatima Jinnah Med Univ. 2011;5:17–24.

Memon A, Shaikh JM et al. Changing Trends in Deliberate Self Poisoning at Hyderabad. JLUMHS 2012, 11:124–126.

Muhammad RAM, Ali Z, Asghar M, Sebtain A, Amer K, Rahim A, Ullah N, Alam I. Etiological and clinical profile of patients presenting with acute poisoning to a teaching hospital.J Postgrad Med Inst2018(1):54–59.

Gravity of Poisoning Cases in Shaheed Benazirabad Sindh, Pakistan: A Prospective Study. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International 2020:89–98.

Nadeem M, Shafeeq M et al. Mortality Indicators of Aluminium Phosphide Poisoning: Experience at DHQ Hospital Rawalpindi.Ann Pak Inst Med Sci2015(11):2.

Naz A, Murad MA, Ashiq A. An Assessment of the Clinical Impact and Profile of regular management in case of Acute Poisoning of Organophosphorus Pesticide. Indo Am J P Sci. 2019;06(03):5953–7.

Owais KKI. Acute poisoning; etiological agents and demographic characteristics in patients coming to ER of a tertiary care hospital.Professional Med J2015(12):1591–1594.

Drug overdose: a wake up call! Experience at a tertiary care centre in Karachi, Pakistan. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 2008, 58:298.

Pechuho SI, Sattar RA, Kumar S, Pechucho TA, Qureshi MA, Khanani MR. Respiratory failure and thrombocytopenia in patients with organophosphorus insecticide poisoning. Rawal Med J. 2014;39:246–50.

Qaisar FSM, Majeed A, Kumar D, Memon A, Memon U. The Epidemiology of Deliberate Self Poisoning presenting in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Hyderabad, Sindh, Pakistan.Br J Med Med Res2014(4):1041–1048.

Qasim AP, Ali MA, Baig A, Moazzam MS. (2016)., 10(1), 26–30.: Emerging Trend of Self Harm by Using ‘Kala Pathar’Hair Dye (Paraphenylene diamine): An Epidemiological Study. Annals of Punjab Medical College (APMC) 2016, 10:26–30.

Qureshi UF, Aslam MN, Ansar MN, et al. Renal manifestation in Kaala Pathar (Paraphenylene Diamine) Poisoning. P J M H S. 2019;13:628–30.

Rahim F, Ullah F, Haroon M, Ashfaq M, Afridi AK. Acute poisoning treated in medical intensive care unit. Gomal J Med Sci. 2016;14:129–32.

Raja KSFM, Bilal A, Qurashi FS, Shaheen M. Organophosphorus compound poisoning; epidemiology and management (atropinization vs pralidoxime) a descriptive analysis, in allied hospital Faisalab. Prof Med J. 2008;15:18–23.

Rana PAFR, Malik SA, Rasheed A. Incidence of fatal poisoning in the city of Lahore: a retrospective study during 1984-88 Lahore.Ann KE Med Coll2000(6):112–115.

Rathore RMU. Morbidity, mortality and management of wheat pill poisoning. J Serv Inst Med Sci. 2007;2:14–8.

Patterns of Suicidal Poisoning Cases in Three Tertiary Care Government Hospitals in Karachi, Pakistan. PAKISTAN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE AND DENTISTRY 2020, 9:51–57.

Sadia SQA, Siddiqui BA, Qasim JA. Human poisoning; prevalence of human poisoning in Sargodha, Pakistan. Prof Med J. 2018;25:316–20.

Sajid NGF, Iqbal S, Qamar un Nisa, Asim SA, Sarwat A, Qasim A, Azmat R. Noor us Saba.: Acute organophosphate poisoning; Electrocardiographic manifestations.Professional Med J2017(10):1461–1465.

Saleem UMS, Ahmad B, Erum A, Azhar S, Ahmad B. Benzodiazepine Poisoning cases: a retrospective study from Faisalabad, Pakistan. Pak J Pharm. 2010;23:11–3.

Shafiq MM, Nadeem M, Iqbal W, Baqai HZ, Ahmed S. I. Rawal Medical Journal: Intentional and accidental poisoning: Experience at a tertiary care hospital in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. 2018(3):381–384.

Mian Mujahid Shah ZH. Adil Jan, Arif: Spectrum of forensic toxicological analysis at Khyber medical college, Peshawar.Pak J Med Res2006, 45.

Shaikh S, Khaskheli MS, Meraj M, Raza H. Effect of Organophasphate poisoning among patients reporting at a tertiary healthcare facility of Sindh Pakistan. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2018;34(3):719–23.

MA. S: Mortality in patients presenting with organophosphorus poisoning at Liaquat University of Medical and Health Sciences.Pak J Med Sci2011(5):1022–1024.

Shazia SKM, Rashid H, Farooq A, Umair M, Syed SU. Two years analysis of acute poisoning in patients presented to Emergency Department of Ayub Teaching Hospital, Abbottabad. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2020;32:628–32.

Shaikh JMSF, Soomro AG. Management of acute organophosphorus insecticide poisoning: an experience at a university hospital.JLUMHS2008(7):96–101.

Shoaib SNM, Khan ZU. Causes and outcome of suicidal cases presented to a medical ward. 2005, 7(1).

Suliman I. The analysis of organophosphates poisoning cases treated at Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Bahawalpur in 2000–2003. Pakistan J Med Sci Online. 2006;22:244–9.

Sultan MO, Khan MI, Ali R et al. Paraphenylenediamine (Kala Pathar) Poisoning at the National Poison Control Center in Karachi: A Prospective Study.Cureus2020,12(e8352).

Muhammad Hussain Tahir JIR, Imran Ul Haq. ACUTE ORGANOPHOSPHORUS POISONING- AN EXPERIENCE. Pak Armed Forces Med J 2006. 2006;56(2):150–6.

Tanweer Sea.: Clinical Profile and Outcome of Paraphenylene Diamine Poisoning.Coll Physicians Surg Pak2018(5):374–377.

Turabi A, Danyal A, Hasan SAUD, Durrani AS, I. F, Ahmed MA. N. S. O. O. R.: Organophosphate poisoning in the urban population; study conducted at national poison control center, Karachi. Biomedica. 2008;24:124–9.

T.Waseem NBB, Raza TH, Nasir NU. A.H.Khan: Myocardial damage after suicidal ingestion of wheat preservative aluminium phosphide. PJC 1997, 8.

Waseem TNM, Irfan K, Waheed I. Poisonings in patients of medical coma and their outcome at Mayo Hospital Lahore. Ann King Edward Med Uni. 2004;16(4):10.

Yousaf M, Ansari RZ, Tanoli AA, Rehman IU, Gul R. Assessment of Poisoning Incidences due to Use of Household Substances in Peshawar. J Gandhara Med Dent Sci. 2018;4:36–41.

Akram A, Shahid RA, Tariq M. Kala Pathar (Paraphenylene Diamine) poisoning; role of tracheostomy: our experience at DHQ Hospitals. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2018;12:865–7.

Qureshi S, Ghazanfar S, Leghari A, Tariq F, Niaz SK, Quraishy MS. Benign esophageal strictures: behaviour, pattern and response to dilatation. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60(8):656–60.

Rafique I, Akhtar U, Farooq U, Khan M, Bhatti JA. Emergency care outcomes of acute chemical poisoning cases in Rawalpindi. J acute disease. 2016;5(1):37–40.

Shaikh MAUI, Memon SH. Evaluation of patients with organophosphorus poisoning at a tertiary care hospital of Sindh.Med Channel2011(3):51–53.

Ghani AAM, Ali M, Nasir S, Shehbaz L, Ali Z. To evaluate the pattern, demographics and etiologies of Acute Poisoning at A Tertiary Care Centre in Karachi Pakistan. APMC. 2017;11:89–93.

Abbas S, Akram S, Riaz M. Organophosphorus poisoning: emergency management in intensive care unit. Prof. 2003;10:308–14.

Akhtar SAUR, Akbar K, Hussain M, Atif M, Shahbaz M. DOI: complications of organophosphorus poisoning. Prof Med J. 2020;27:2149–53.

Zohaib A, Maheen N, Ahmed J, Mohammad A, Kayhan H, Muhammad A. A retrospective analysis on poison related Mortalities in a Tertiary Care Centre in Pakistan. Asia Pac J Med Toxicol. 2020;9(3):85–90.

Ahmad RAK, Iqbal R. Acute poisoning due to commercial pesticides in Multan.Pak J Med Sci2002(227–31).

Ahmad I, Rehman HU, Iqbal J. CLINICAL PROFILE AND IMPACT OF PROPER TREATMENT IN ACUTE ORGANOPHOSPHORUS PESTICIDE POISONING. JSZMC. 2010;1(3):91–3.

Ahmad A, Imran Z, Asad U, THE TREND OF ACUTE POISONING CASES PRESENTED TO THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT OF A TEACHING HOSPITAL.WORLD JOURNAL OF PHARMACEUTICAL AND MEDICAL RESEARCH. 2019:249–252.

Ahmed AAL, Shehbaz L et al. Prevalence and characteristics of organophosphate poisoning at a tertiary care centre in Karachi, Pakistan. 2016:32(34):269–273.

Ahmad EAM, Ehsan S, Riaz S, Fayyaz N, Ashfaq M. Frequency of Acute Poisoning Cases Presented to Allied Hospital Emergency during March, 2017 to February, 2018. APMC 2019 2019((4)):292–295.

Akbar K, Iqbal J, ur, Rehman H, Iqbal R. ACUTE RENAL FAILURE AMONG KALA PATHAR POISONING PATIENTS. JSZMC 2017, 8:1153–1156.

Kermani F, Ather NA, Ara J. Deliberate self-harm: frequency and associated factors. J Surg Pak Int. 2006;11(1):34–6.

Noor NAQN, Chaudhry GM, Masood M, Hashmat MA, Asif AH. Acute poisoning in adults in Multan. JPMA 1988,J Pak Med Assoc.: 305–306.

Qureshi MANS, Ahmed T, Tariq F, Rehman H, Qasim AP. Aluminium Phosphide Poisoning: Clinical Profile and Outcome of Patients Admitted in a Tertiary Care Hospital. APMC 2018, 12:191–194.

Sattar R, Sultan MO, Jamil MA et al. Demography and outcome off acute adult poisoning patients admitted in a tertiary care hospiotal: a one year analysis.Ann Jinnah Sindh Med Uni(1):21–24.

Jamil HKA, Akhtar S, Sultana N. Organo-phosphorus insecticide poisoning-review of 53 cases.J Pak Med Assoc1977(27):361–363.

Eddleston M. Patterns and problems of deliberate self-poisoning in the developing world. QJM: monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 2000;93(11):715–31.

Banjaj R, Wasir H. Epidemic aluminium phosphide poisoning in northern India. The lancet. 1988;331(8589):820–1.

Eddleston M. Applied clinical pharmacology and public health in rural asia – preventing deaths from organophosphorus pesticide and yellow oleander poisoning. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75(5):1175–88.

Lotti M. Chap. 51 - clinical toxicology of Anticholinesterase Agents in humans. Second ed. Edition edn: Elsevier Inc; 2001. pp. 1043–85.

Dawson AH, Eddleston M, Senarathna L, Mohamed F, Gawarammana I, Bowe SJ, Manuweera G, Buckley NA. Acute human lethal toxicity of agricultural pesticides: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000357.

Buckley NA, Fahim M, Raubenheimer J, Gawarammana IB, Eddleston M, Roberts MS, Dawson AH. Case fatality of agricultural pesticides after self-poisoning in Sri Lanka: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet Global health. 2021;9:e854–62.

Ghazi MA. Wheat pill (aluminum phosphide) poisoning”; Commonly ignored dilemma. A comprehensive clinical review.Professional Medical Journal2013(6):855–863.

Hassan Ur R, Valeed, Bin. Mansoor,Fibhaa, Syed, Mohammad Ali, Arif, Ayesha, Javed: Wheat pill poisoning: complications and management.Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association2021:1–8.

Karunarathne Ayanthi BA, Sethi Aastha P, Uditha E. Importance of pesticides for lethal poisoning in India during 1999 to 2018: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1441.

Jayaraman K. Death pills from pesticide. Nature. 1991;353(6343):377–7.

Kabra S, Narayanan R. Aluminium phosphide: worse than Bhopal. The Lancet. 1988;331(8598):1333.

Chugh S, Ram S, Arora B, Malhotra K. Incidence & outcome of aluminium phosphide poisoning in a hospital study. Indian J Med Res. 1991;94:232–5.

Buckley NA, Fahim M, Raubenheimer J, Gawarammana IB, Eddleston M, Roberts MS, Dawson AH. Case fatality of agricultural pesticides after self-poisoning in Sri Lanka: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet global health. 2021;9(6):e854–62.

Knipe DW, Chang S-S, Dawson A, Eddleston M, Konradsen F, Metcalfe C, Gunnell D. Suicide prevention through means restriction: Impact of the 2008–2011 pesticide restrictions on suicide in Sri Lanka (vol 12, e0172893, 2017). PloS one 2017, 12(4).

Knipe DW, Gunnell D, Eddleston M. Preventing deaths from pesticide self-poisoning-learning from Sri Lanka’s success. 2017.

Gunnell D, Knipe D, Chang S-S, Pearson M, Konradsen F, Lee WJ, Eddleston M. Prevention of suicide with regulations aimed at restricting access to highly hazardous pesticides: a systematic review of the international evidence. The Lancet global health. 2017;5(10):e1026–37.

Bonvoisin T, Utyasheva L, Knipe D, Gunnell D, Eddleston M. Suicide by pesticide poisoning in India: a review of pesticide regulations and their impact on suicide trends. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):251–216.

Murali R, Bhalla A, Singh D, Singh S. Acute pesticide poisoning: 15 years experience of a large north-west indian hospital. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2009;47(1):35–8.

Ghimire R, Utyasheva L, Pokhrel M, Rai N, Chaudhary B, Prasad PN, Bajracharya SR, Basnet B, Das KD, Pathak NK, et al. Intentional pesticide poisoning and pesticide suicides in Nepal. Clin Toxicol. 2022;60:46–52.

Utyasheva L, Sharma D, Ghimire R, Karunarathne A, Robertson G, Eddleston M. Suicide by pesticide ingestion in Nepal and the impact of pesticide regulation. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1136.

Sarfraz Hussain MAK. Muhammad Javaid Ahmad, Ehsan ul Haq, Sarfraz Nawaz, Ghulam Yaseen, Safia Riaz, Muhammad Arif, Khaliq ur Rehman Arshad. Zia Chish: ASSESSMENT OF PESTICIDES FOR QUALITY CONTROL UNDER PESTICIDE REGULARITY PROGRAMME; 2020.

Manuweera G, Eddleston M, Egodage S, Buckley NA. Do targeted Bans of Insecticides to prevent deaths from self-poisoning result in reduced agricultural output? Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(4):492–5.

Chowdhury FR, Dewan G, Verma VR, Knipe DW, Isha IT, Faiz MA, Gunnell DJ, Eddleston M. Bans of WHO Class I Pesticides in Bangladesh-suicide prevention without hampering agricultural output. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(1):175–84.

Eddleston M, Adhikari S, Egodage S, Ranganath H, Mohamed F, Manuweera G, Azher S, Jayamanne S, Juzczak E, Sheriff MHR, et al. Effects of a provincial ban of two toxic organophosphorus insecticides on pesticide poisoning hospital admissions. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2012;50(3):202–9.

Swanson JWP, McGinty EEPMS, Fazel SMMDF, Mays VMPM. Mental illness and reduction of gun violence and suicide: bringing epidemiologic research to policy. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(5):366–76.

Rivara FP. Youth suicide and Access to guns. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(5):429–30.

Chang SS, Chen YY, Yip PS, Lee WJ, Hagihara A, Gunnell D. Regional changes in charcoal-burning suicide rates in East/Southeast Asia from 1995 to 2011: a time trend analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(4):e1001622.

Lin CY, Hsu CY, Chen YY, Chang SS, Gunnell D. Method-Specific Suicide Rates and Accessibility of Means. Crisis 2021.

Bierens J, Hoogenboezem J. Fatal drowning statistics from the Netherlands – an example of an aggregated demographic profile. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):339–9.

Morgan HG. Suicide. Edited by Alec Roy. London: Williams & Wilkins. 1986. Pp 205. £27.00. British journal of psychiatry 1987, 150(3):423–423.

Shekhani SS, Perveen S, Akbar K, Bachani S, Khan MM. Suicide and deliberate self-harm in Pakistan: a scoping review. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):1–15.

Phillips MR, Yang G, Zhang Y, Wang L, Ji H, Zhou M. Risk factors for suicide in China: a national case-control psychological autopsy study. The Lancet (British edition). 2002;360(9347):1728–36.

Yip PS, Caine E, Yousuf S, Chang SS, Wu KC, Chen YY. Means restriction for suicide prevention. Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2393–9.

World Health Organization. Preventing suicide. A global imperative. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

Rotterdam, Convention. http://www.picint/TheConvention/Chemicals/DecisionGuidanceDocuments/tabid/2413/language/en-US/DefaultaspxSept.1998.

A letter in. response to the Special Rapporteur’s questionnaire to prepare annual report of the implications on the wide spread use of pesticides on right to food from ‘Permanent Mission of Pakistan to the United Nations and other International Organanizations’. 6th December 2016.

Acknowledgements

The Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention is funded by a grant from Open Philanthropy, at the recommendation of GiveWell, USA. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Funding

This research work was not directly funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr.Michael Eddleston and Shweta Dabholkar wrote the main manuscript.

Shweta Dabholkar conducted literature review and prepared figures and tables. Shahina Pirani conducted the literature review on the pesticide poisoning data. Dr.Murad Khan provided information on suicide cases in Pakistan.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Dabholkar, S., Pirani, S., Davis, M. et al. Suicides by pesticide ingestion in Pakistan and the impact of pesticide regulation. BMC Public Health 23, 676 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15505-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15505-1