Abstract

Background

The United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030) seeks to create multisectoral changes that align healthy ageing with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Given that the SDGs have completed their first five years, the objective of this scoping review was to summarise any efforts launched to directly address the SDGs in older adults in community settings prior to the Decade. This will contribute to providing a baseline against which to track progress and identify gaps.

Methods

Following Cochrane guidelines for scoping reviews, searches were conducted in three electronic databases, five grey-literature websites, and one search engine between April to May 2021; and limited to entries from 2016 to 2020. Abstracts and full texts were double-screened; references of included papers were searched to identify additional candidate publications; and data were extracted independently by two authors, using an adaptation of existing frameworks. Quality assessment was not conducted.

Results

In total, we identified 617 peer-review papers, of which only two were included in the review. Grey literature searches generated 31 results, from which ten were included. Overall, the literature was sparse and heterogeneous, consisting of five reports, three policy documents, two non-systematic reviews, one city plan, and one policy appraisal. Initiatives targeting older adults were mentioned under 12 different SDGs, with SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 3 (Good Health and Wellbeing), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) being the most commonly discussed. Also, SDG-based efforts frequently overlapped or aligned to the eight domains of age-friendly environments outlined in the World Health Organisation framework.

Conclusion

The review has documented the extent, range, and nature of available research and provided an initial evidence backdrop for future research and policy development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The world’s population is ageing fast. By 2050, the global population will increase by two billion [1], and persons aged over 65 – who already form the fastest-growing age group – will outnumber young people aged 15 to 24 [2]. Ageing is a multisectoral challenge with economic, social, and health effects that will put unprecedented pressure on health, welfare, and social care systems [3]. Population ageing has far-reaching implications for our planet, not least as a major driver of population growth that further increases demands on natural resources and ecosystems [4]. This has fundamental impacts on sustainable development efforts to eradicate poverty, achieve food security, and build inclusive, resilient communities. Conversely, population ageing also creates opportunities and societal advantages, as older adults contribute to their communities via work, volunteering, and informal care [5, 6]. Older people are a resource to society that will play an increasingly vital role in the future.

Healthy ageing, a concept adopted by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2015, is key to empowering the contribution of older people to society and maximising their well-being throughout life [2]. It is defined as “a process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age”, where “well-being” is considered holistically to include happiness, satisfaction, and fulfilment, and “functional ability” denotes the health-related attributes that enable people to be and to do what they value [7]. The WHO affirms that ageing is not a purely biological process: it is influenced by external factors like the built environment, societies and communities, policies, services, and systems [7]. The environments older people live and work in must enable healthy ageing by supporting their autonomy and encouraging greater connectivity, security, and identity [7].

Over the last 20 years, there have been many international policy developments related to healthy ageing, including the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing (2002) [8], Active ageing: a policy framework (2002) [9], the World report on ageing and health (2015) [7], and the Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health (2017) [10]. Concomitantly, international policy has focused on sustainable development, with the United Nations (UN) introducing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2016. The Agenda outlined 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), that aim to eradicate poverty and hunger, protect the planet, foster peace and justice, and mobilise partnerships for sustainable development [11, 12]. The most recent policy development, the UN Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030), seeks to attain both healthy ageing goals and SDGs by empowering strategies proposed by its predecessors (like the development of age-friendly environments and systems for long-term care [7, 10]) and encouraging multisectoral action on healthy ageing [13]. Specifically, the Decade aims to transform four areas of action and 11 SDGs related to healthy ageing [13]. Prior to this development, there has been a limited focus within the SDGs on older adults – very few goals mention older adults, with the group often being referenced alongside other vulnerable populations like children and people with disabilities. Therefore, the Decade is unique, tying together healthy ageing and SDGs for the first time, to make the Goals actionable and relevant to older adults.

The Decade has brought attention to healthy ageing and highlighted its importance to meeting the SDGs. But the SDGs have already completed their first five years. Have any recommendations, policies, interventions, or indicators addressed the SDGs in older populations prior to the Decade? This scoping review investigates this question. Specifically, it examines the extent, range, and nature of research that addresses the SDGs in community settings, with a focus on older adults.

The focus on community settings stems from the ongoing importance of the concept of “age-friendly cities and communities” within international policy documents [14]. Environments, specifically communities, are thought of as being central to healthy ageing as they promote health and eliminate barriers – this is demonstrated by the renewed commitments to enhance the Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities within the Decade. For the purposes of the review, a community was defined as “a directly elected or mandated public governing body possessing within a given territory, as defined by law, a set of competences to deliver public goods and services to citizens; inclusive of sub-national organisational levels from the provincial or state level, to villages and townships with limited population numbers”. This is the definition used in the Terms of Reference for the membership in the Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities [15].

Methods

In keeping with the Cochrane guidelines, we chose a scoping review approach because the literature has not previously been comprehensively reviewed and is heterogeneous in nature, consisting of peer-reviewed literature, international and national policy documents, and policy appraisals [16]. Searches were conducted between April and May 2021; peer-reviewed literature searches (in Scopus, Medline, and Global Health databases) were followed by grey literature searches (in Google and on the websites of the UN, WHO, Centre for Ageing Better, International Federation of Ageing, and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). The searches were limited to a four year period, running from the introduction of the SDGs (in January 2016 [11]) to the start of the Decade of Healthy Ageing (in January 2021 [17]). Grey literature searches were limited to the first 100 results. Table 1 depicts the search strategy; the searches were adapted for each database to be reproducible.

First, titles were screened by VS; then, abstracts and full texts were double screened by VS and CM, with discrepancies resolved via discussion. After screening and inclusion of papers, reference lists of the peer-reviewed articles were searched to avoid any data being omitted; also, forward searches were conducted to identify relevant papers that referenced the peer-reviewed articles.

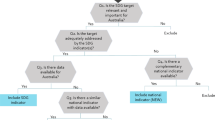

Extraction of data from each document or study was streamlined using adaptations of existing frameworks [18]. We summarised the results narratively and descriptively to align with the objectives of the review. Quality assessment is not a standard procedure for scoping reviews [16] and was not conducted. However, a SPIDER search tool, which determined the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review, was used (provided in Supplementary Table 1). The document selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Results

Table 2 provides the outlines and titles of the SDGs, to make the results more digestible [19].

Description of the results

Overall, we identified 617 references through initial searches of bibliographic databases, from which two papers were included (Table 3). Grey literature searches across six websites and search engines generated 31 results, from which ten were included in the review (Table 4).

Most of the literature consisted of reports from international or national organisations [20,21,22,23,24], although three policy documents [25,26,27], one policy appraisal [28], and two non-systematic reviews [29, 30] were also included. The literature largely focused on macro- (n = 4) [23–[24, 28]–29] or meso-level (n = 4) [20,21,22, 31] initiatives; some of the documents provided “recommendations” [25,26,27] which were difficult to categorise, as they could be applied at multiple levels. All but one documents reviewed existing actions which addressed the SDGs (one document [31] detailed ambitions which, if achieved, would address the SDGs). The majority of documents (n = 7) focused on high-income countries or regions, of which four focused on the United Kingdom [20,21,22, 31]. One review [29] and two documents [23, 28] discussed the SDGs related to older adults in low- and middle-income countries. Overall, initiatives targeting older adults were mentioned under 12 different SDGs: SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 3 (Good Health and Wellbeing), SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), SDG 13 (Climate Action), SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions), and SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals). Despite the initiatives being connected to a range of SDGs, there was variation in how commonly particular targets were reported – some papers provided targets for all referenced SDGs, others provided no targets, and a few provided targets for specific SDGs only.

Commonly discussed Sustainable Development Goals

SDG 11, SDG 3, SDG 1, and SDG 10 were the most commonly discussed Goals in the literature. Specifically, nine documents mentioned SDG 11, seven mentioned SDG 3, six mentioned SDG 1, and five mentioned SDG 10.

Recommendations or initiatives targeting SDG 11 frequently considered green spaces, affordability of housing, and accessibility of transport. Walkability was mentioned in a paper specific to low-income countries [29]. Initiatives or recommendations made under SDG 10 were variable and included pension schemes and advocacy as well as programmes for dementia awareness, social protection, and social participation. Efforts under SDG 1 discussed financial assistance, affordable transport, financial security programs (including poverty prevention and pensions), and affordable housing. Conversely, strategies under SDG 3 mostly addressed early treatment and assessment for dementia, preventative medicine, accessibility of care services, and flexible homes for ageing in place.

Rarely discussed Sustainable Development Goals

Eight other SDGs were mentioned in the literature (Tables 2 and 3); generally, these were not discussed as often (i.e., in more than three papers at a time). In particular, the literature highlighted shortcomings in SDGs 2, 4, 5, and 17 as only some countries provided older adult-specific initiatives that aim to address these goals. A policy paper focused on SDG 5 recommended social care and pension reforms to meet the Goal; the policy brief also considered the importance of affordable services [26]. Goals 13 and 17 were only briefly mentioned; strategies under SDG 17 discussed the need for disaggregated data [27], and those under SDG 13 considered disaster risk management targeted at older adults [23]. Interestingly, one report highlighted the importance of digital inclusion for older people under SDG 9 [31].

The intersection of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Often, the initiatives and recommendations under individual SDGs overlapped. For example, SDGs 1, 5, and 10 addressed financial security; SDGs 1, 10, and 16 discussed advocating for older people through policy or legislation; and SDGs 5, 8, and 10 mentioned the importance of gender equality. The most commonly discussed efforts concerned the protection of older adults and social participation, with the former appearing across SDGs 1, 8, 10, and 16 and the latter appearing across SDGs 3, 8, 10, and 11. However, not all SDGs intersected in their recommendations, as initiatives under SDGs 2, 4, 9, 13, and 17 did not discuss efforts similar to any other Goals.

High-income versus low- and middle-income countries

Eight out of twelve sources focused entirely on high-income regions (according to the World Bank classification of economies [32]). Specifically, a document that analysed 111 voluntary national reports from countries of all economic strata did not elucidate differences between low- or middle-income countries and high-income ones in the types of efforts used to address SDGs 1, 2, 3, 8, 10, and 11 (all types of countries had examples of efforts) [23]). For SDGs 4, 5 and 13, no examples from low- and middle-income countries were available; similarly, few examples (three for SDG 4, two for SDG 5, and one for SDG 13) were available from high-income countries [23]. Another document that appraised reports from Western Asian countries considered eight low- and middle-income countries and two high-income ones [28]. With the exception of one targeted anti-poverty programme (in Kuwait), high-income countries did not differ considerably in their strategies, though they did evidence greater participation of older people in policy and programme development (largely through civil society organisations) [28]. A peer-reviewed paper that focused solely on recommendations for “developing countries” discussed how these nations have poor pedestrian facilities and public transport compared to high-income ones [29]. Despite high-income countries having many established free transport schemes and financial security programmes, a focus on SDGs 1, 3, 10, and 11 was still present across many documents [20,21,22, 24]. Overall, countries within different economic strata did not focus on markedly different goals.

Discussion

The scoping review has highlighted that schemes, recommendations, or policies concerning older adults were most frequently mentioned under SDGs 1, 3, 10, and 11. Conversely, the literature had limited examples of actions under SDGs 2, 4, 5, and 17. The review summarised the existing efforts that aimed to directly address the SDGs in older populations (in a community setting) prior to the Decade of Healthy Ageing and demonstrated the extent of available research.

The documents discussed many types of actions that are needed to improve the lives of older adults as part of the SDGs. For example, financial security, affordable healthcare, accessibility of services, affordable housing, social participation, and inclusion and protection were addressed. These topics are similar to the ones outlined by an important policy document related to ageing and communities, the WHO Global age-friendly cities: a guide, which also discusses healthcare, housing, transport, social inclusion, and participation as vital to healthy ageing [33]. These topics are mentioned as part of the eight domains of age-friendly environments, which reflect the physical structures, environment, services, and policies of communities that foster healthy and active ageing [7, 33]. Some other relevant topics were mentioned: with outdoor environments being addressed as part of SDGs 11 and 13 [29], civil engagement and employment as part of SDG 8 [23, 27, 28], and community services and ageing-in-place initiatives as part of the SDG 1 and SDG 11 [25].

However, the Communication and Information domain of the WHO framework was not specifically addressed by the literature identified. While the WHO guidelines highlight the importance of clear, accessible information and the need to humanise some automated processes [33], the initiatives under SDG 9 addressed digital inclusion only briefly, and information provision not at all [31].

The actions launched to support the SDGs were generally similar to those discussed under the eight domains of age-friendly environments, exemplifying the continuity within policy on what is required for healthy ageing.

Interestingly, the SDG-targeted actions overlapped significantly. For example, a focus on inclusion and protection of older adults and social participation was present across four (different) SDGs. Likewise, three Goals focused on pensions, financial security, and gender equality. Existing papers have remarked on the interlinkages between the SDGs, noting that some interactions result in co-benefits, and others lead to trade-offs [34, 35]. For example, studies have argued that progress on any Goal is likely to support health, which the UN reiterates through its nexus mapping (pattern of SDG interactions) where SDG 3 is linked to SDG 1, 10, and 11 [34, 36]. Thus, it is unsurprising that the initiatives and recommendations discussed under the various Goals overlap, as the SDGs were designed to relate to and depend on one another [35]. Despite this alignment, efforts may only focus on a single SDG due to fragmented governance, research, and institutions [35], a situation likely influenced by local priorities and funding.

One important finding of the review was that few studies presented SDG-centred schemes specifically targeted at older adults. Some studies excluded from the review did discuss initiatives that target “vulnerable populations” [37,38,39,40], a term that aggregates older people, children, women, and people with disabilities. But these four groups potentially have very different needs. Similarly, some of the included reports suggested that general strategies be used to address the SDGs in older populations, but few explicitly targeted older adults. Moreover, some papers discussed age-related strategies in the context of “leaving no one behind” without linking them to a specific SDG [23].

This lack of focus on older adults within SDG-related initiatives is somewhat unsurprising given the limited attention within the SDGs on older adults. Only SDG 2, 3, 10, and 11 make a nod to age or older people within their specific targets. Despite the Goals being designed in a way to “cover issues that affect us all” there is limited appreciation of the unique needs of “vulnerable” groups within them – people with disabilities, children, women, and older adults are often aggregated under the same targets [41]. This lack of focus could result in limited funding for SDG-related programmes targeting older adults, as countries and communities may not prioritise older adults and therefore not invest in programmes related to this group. Moreover, communities may not be able to bid for funding from the UN SDG Fund for projects related to older people, given the lack of focus within the SDG agenda – projects under this fund focus on children or women instead [42]. There are projects under the Age-friendly Cities and Communities initiative that can be thought to address the SDGs (without specifically referencing them), given the alignment between the two policy agendas (as demonstrated by the Decade of Healthy Ageing). However, these were out of the scope of the review, which aimed to elucidate any programmes specific to the SDGs.

Overall, sustainable development projects lack precision and focus on older adults, and the literature centres on high-income regions that are more likely to provide regular national or subnational reports. Two documents that appraised reports by high-, middle- and low-income countries did not elucidate any obvious differences in the types of SDG-based efforts discussed. Nor can in-depth conclusions be reached about discrepancies or similarities between countries of different economic strata, since few reports were available from individual low- or middle-income countries.

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review has important methodological strengths. The comprehensive search strategy allowed the review to clarify the type of documents available, the extent of the literature, and its nature. Extensive peer-reviewed searches reduced the likelihood of missing any crucial data; while the grey literature searches reduced the risk of publication bias and increased the comprehensiveness of the review [43].

This review does have some methodological shortcomings, such as grey literature searches that focus on reports written in English, shifting the balance towards high-income countries. Ideally, the websites of individual UN bodies, country offices, other age-related and sustainability focused organisations, and reference lists of the policy documents would have been searched to obtain larger samples. This is the object of further research to better understand the alignment, or the lack thereof, between global healthy ageing and sustainability policies.

The scoping nature of the review also limited its analytical depth – although this was not entirely relevant to the aims. The review aimed to showcase the range of literature rather than providing a synthesis of the results. The scope of the review was narrowed to make it relevant in the context of the Decade and other healthy ageing policies, which focus on the “community” as a setting. Despite this potentially restricting the volume of literature obtained, “community” was defined in a broad sense, and initiatives at several (meso- and macro-) levels were included.

Conclusion

The scoping review has revealed useful findings, namely the concentrated efforts targeting older people under SDGs 1, 3, 10, and 11 and the complementary and overlapping nature of the SDG-based efforts. Despite the limited research available on SDG-targeted efforts focussed on older adults, the review findings do align with the eight domains of age-friendly environments. Overall, the review has achieved its aim of summarising the extent, range, and nature of available research. It provides an initial evidence backdrop for future research and policy development that can strengthen the links between healthy ageing and sustainability agendas, and articulates how progress should be monitored.

Data availability

All data analysed during this study are included in this article. Specifically, data used in this study can be found in the following databases: Scopus, Medline, and Global Health. Also, Google, and the websites of the UN, WHO, Centre for Ageing Better, International Federation of Ageing, and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Search were searched. Search strings are shown in Table 1.

References

United Nations. Shifting Demographics. United Nations [date unknown]. https://www.un.org/en/un75/shifting-demographics. Accessed 25 Mar 2021.

Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Ageing 2017 Highlights. Report No.: (ST/ESA/SER.A/397). United Nations 2017. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2017_Highlights.pdf. Accessed 28 Mar 2021.

Office for National Statistics. Living longer: how our population is changing and why it matters. Office for National Statistics 2018. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ageing/articles/livinglongerhowourpopulationischangingandwhyitmatters/2018-08-13. Accessed 25 Mar 2021.

Mavrodaris A, Powell J, Thorogood M. Prevalences of dementia and cognitive impairment among older people in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(10):773–83.

The Government Office for Science. Future of an Ageing Population. Government Office for Science 2016 (updated 11 June 2019). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/816458/future-of-an-ageing-population.pdf. Accessed 14 Mar 2021.

Nazroo JY. Volunteering, providing informal care and paid employment in later life: role occupancy and implications for well-being. Government Office for Science 2015 May. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/434398/gs-15-5-future-ageing-volunteering-er20.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2021.

World Health Organisation. World report on ageing and health. World Health Organisation 2015. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/186463/9789240694811_eng.pdf;jsessionid=C8663BF9F3D1E6D08498250C1AACB5A3?sequence=1. Accessed 13 Mar 2021.

United Nations. Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing. United Nations 2002. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/ageing/MIPAA/political-declaration-en.pdf. Accessed 25 Mar 2021.

World Health Organisation. Active Ageing A Policy Framework. World Health Organisation 2002. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/67215/WHO_NMH_NPH_02.8.pdf;jsessionid=154BD8E861A28358DE2C98BA7487A7A2?sequence=1. Accessed 26 Mar 2021.

World Health Organisation. Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health. World Health Organization 2017. https://www.who.int/ageing/WHO-GSAP-2017.pdf. Accessed 28 Mar 2021.

United Nations. The Sustainable Development Agenda. United Nations 2018. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda-retired/. Accessed 28 Mar 2001.

Rosa W, [Ed]. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In: A New Era in Global Health 2017. http://connect.springerpub.com/lookup/doi/10.1891/9780826190123.ap02. Accessed 28 Mar 2021.

United Nations. Decade of Healthy Ageing 2020–2030. United Nations 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/decade-of-healthy-ageing/final-decade-proposal/decade-proposal-final-apr2020-en.pdf. Accessed 13 Mar 2021.

Rudnicka E, Napierała P, Podfigurna A, Męczekalski B, Smolarczyk R, Grymowicz M. The World Health Organization (WHO) approach to healthy ageing. Maturitas. 2020 Sep;139:6–11.

World Health Organisation. Membership to the Global Network.Age-Friendly World2020. https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/membership/

The Cochrane Collaboration. Scoping reviews: what they are and how you can do them. The Cochrane Collaboration 2020. https://www.training.cochrane.org/resource/scoping-reviews-what-they-are-and-how-you-can-do-them. Accessed 27 Mar 2021.

World Health Organisation. Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030). World Health Organisation 2020. https://www.who.int/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing. Accessed 9 Apr 2021.

Joanna Briggs Institute. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI 2020. https://wiki.jbi.global/display/MANUAL/11.2.7+Data+extraction. Accessed 6 Apr 2021.

United Nations. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations 2022. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

Canterbury SDGF. Canterbury Sustainable Development Goals Forum Reports on local implementation of the Goals. Canterbury SDG Forum 2019. https://media.www.kent.ac.uk/se/14759/SDGForumReport2019.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr 2021.

HM Government. Voluntary National Review of progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. HM Government 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/816887/UK-Voluntary-National-Review-2019.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr 2021.

Fox S, Macleod A. Cabot Institute for the Environment, University of Bristol. Bristol And the SDGs A Voluntary Local Review of Progress 2019. University of Bristol 2019. https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/cabot-institute-2018/documents/BRISTOL%20AND%20THE%20SDGs.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr 2021.

United Nations. Ageing Related Policies and Priorities in the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development – As reported in the Voluntary National Reviews of 2016, 2017 and 2018. United Nations 2018. https://www.un.org/development/desa/ageing/wp-content/uploads/sites/24/2019/07/Analysis-Ageing_VNRs_Final28122018.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr 2021.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Singapore. Towards a Sustainable and Resilient Singapore Singapore’s Voluntary National Review Report to the 2018 UN High Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development. Singapore Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2018. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/19439Singapores_Voluntary_National_Review_Report_v2.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr 2021.

UNECE. Ageing in sustainable and smart cities UNECE Policy Brief on Ageing No. 24.UNECE 2020. https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/pau/age/Policy_briefs/ECE_WG-1_35.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr 2021.

UNECE. Gender equality in ageing societies UNECE Policy Brief on Ageing No. 23. UNECE 2020. https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/pau/age/Policy_briefs/ECE_WG-1_34.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr 2021.

Stakeholder Group on Ageing. Position paper submitted to the High Level Political Forum 2019 Empowering People And Ensuring Inclusiveness And Equality. Stakeholder Group on Ageing 2019. https://www.stakeholdergrouponageing.org/file%20library/position%20papers/final-sga-position-paper-hlpf-2019.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr 2021.

UNESCWA. Ageing in ESCWA Member States: Third Review and Appraisal of the Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing. Report No.: E/ESCWA/SDD/2017/Technical Paper.12. United Nations 2017. https://www.unescwa.org/sites/www.unescwa.org/files/publications/files/ageing-escwa-member-states-english_3.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr 2021.

Devarajan R, Prabhakaran D, Goenka S. Built environment for physical activity –An urban barometer, surveillance, and monitoring. Obes Rev. 2020;21(1):e12938.

Mihnovits A, Nisos CE. Measuring healthy and suitable housing for older people: a review of international indicators and data sets. Gerontechnology. 2016;15(1):17–24.

Bristol One City. One City Plan and the Sustainable Development Goals. Bristol City Office 2019. https://www.bristolonecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/One-City-Plan-Goals-and-the-UN-Sustainable-Development-Goals.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr 2021.

World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. World Bank 2021 https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 24 Oct 2020.

World Health Organisation. Global Age-friendly Cities: A Guide. World Health Organisation 2007. https://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Global_age_friendly_cities_Guide_English.pdf. Accessed 29 Mar 2021.

Nilsson M, Chisholm E, Griggs D, Howden-Chapman P, McCollum D, Messerli P, Neumann B, Stevance AS, Visbeck M, Stafford-Smith M. Mapping interactions between the sustainable development goals: lessons learned and ways forward. Sustain Sci. 2018;13(6):1489–503.

Scharlemann JPW, Brock RC, Balfour N, Brown C, Burgess ND, Guth MK, Ingram DJ, Lane R, Martin JG, Wicander S, Kapos V. Towards understanding interactions between Sustainable Development Goals: the role of environment–human linkages. Sustain Sci. 2020;15(6):1573–84.

A Nexus Approach for the SDGs. United Nations 2016. https://www.un.org/ecosoc/sites/www.un.org.ecosoc/files/files/en/2016doc/interlinkages-sdgs.pdf. Accessed 25 Apr 2021.

Diaz-Sarachaga JM. Analysis of the local agenda 21 in Madrid compared with other global actions in sustainable development. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(19):3685.

Ramirez-Rubio O, Daher C, Fanjul G, Gascon M, Mueller N, Pajín L, Plasencia A, Rojas-Rueda D, Thondoo M, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ. Urban health: an example of a “health in all policies” approach in the context of SDGs implementation. Global Health. 2019;15(1):1–21.

Giles-Corti B, Lowe M, Arundel J. Achieving the SDGs: evaluating indicators to be used to benchmark and monitor progress towards creating healthy and sustainable cities. Health Policy. 2020;124(6):581–90.

Al-Mandhari A, El-Adawy M, Khan W, Ghaffar A. Health for all by all-pursuing multi-sectoral action on health for SDGs in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region. Global Health. 2019;15(1):1–4.

United Nations. Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals: Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. UN.org. 2015. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/owg.html

United Nations. A UN mechanism to invest in joint partnerships for SDGs. Sustainable Development Goals Fund 2014. https://www.sdgfund.org/who-we-are#:~:text=National%20and%20international%20partners%2 C%20including

Paez A. Gray literature: an important resource in systematic reviews. J Evid Based Med. 2017;10(3):233–40.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Andy Cowan for providing editorial support with the submission and the cover letter.

Funding

The study was not funded by any body and was conducted as part of an MPhil in Public Health at the University of Cambridge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (VS, CM, and LL) contributed to the design of the study, and reading and approval of the manuscript. CM and VS double-screened the texts included in the scoping review. VS was responsible for the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shevelkova, V., Mattocks, C. & Lafortune, L. Efforts to address the Sustainable Development Goals in older populations: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 23, 456 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15308-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15308-4