Abstract

Background and aims

This systematic review sought to identify, explain and interpret the prominent or recurring themes relating to the barriers and facilitators of reporting and recording of self-harm in young people across different settings, such as the healthcare setting, schools and the criminal justice setting.

Methods

A search strategy was developed to ensure all relevant literature around the reporting and recording of self-harm in young people was obtained. Literature searches were conducted in six databases and a grey literature search of policy documents and relevant material was also conducted. Due to the range of available literature, both quantitative and qualitative methodologies were considered for inclusion.

Results

Following the completion of the literature searches and sifting, nineteen papers were eligible for inclusion.

Facilitators to reporting self-harm across the different settings were found to be recognising self-harm behaviours, using passive screening, training and experience, positive communication, and safe, private information sharing. Barriers to reporting self-harm included confidentiality concerns, negative perceptions of young people, communication difficulties, stigma, staff lacking knowledge around self-harm, and a lack of time, money and resources.

Facilitators to recording self-harm across the different settings included being open to discussing what is recorded, services working together and co-ordinated help. Barriers to recording self-harm were mainly around stigma, the information being recorded and the ability of staff being able to do so, and their length of professional experience.

Conclusion

Following the review of the current evidence, it was apparent that there was still progress to be made to improve the reporting and recording of self-harm in young people, across the different settings. Future work should concentrate on better understanding the facilitators, whilst aiming to ameliorate the barriers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Self-harm can be defined as an individual causing injury or poisoning to themselves, regardless of its intent [1]. It can include a plethora of different behaviours including hitting, cutting, poisoning or burning [1]. The presence of self-harm can be triggered by complex, heterogeneous factors, but it is commonly associated with mental illness, with individuals at an increased risk of suicide and attempted suicide. Prevalence rates of self-harm illuminate several at-risk groups when filtered by gender, region, ethnicity, and/or age. Public Health England’s (PHE) data shows that in 2019/20, 694.8 per 100,000 population of females and 196.6 per 100,000 population of males, aged 10–24 years, were admitted to hospital as a consequence of self-harm [2]. This disparity in self-harm rates between females and males remains consistent within prevalence estimates [3, 4], with McManus et al. [5] noting the greatest increase in self-harm rates being attributable to young women and girls. Similarly, the PHE data exposes considerable regional variations in hospital admissions resulting from self-harm in children and young people [2]. Such disparities have frequently been correlated to socioeconomic deprivation [6, 7], or discrepancies between the management of self-harm between hospitals [8, 9]. When comparing rates between ethnic groups, research indicates that black females are the most at-risk group [10, 11], though the data is generally limited in this area.

Young people and children are thought to be the most at-risk group, with rates generally declining with age after 25 years [5, 12]. Research has demonstrated that self-harm amongst children and adolescents in the UK has increased over the last two decades [13, 14], particularly for girls [15]. There have been several hypotheses as to why this increase has occurred. For example, one study has found increased rates of self-harm amongst adolescents with a friend who had self-harmed previously [16]. Additionally, Geulayov et al. (2022) [17] illuminated the link between loneliness during the Covid-19 pandemic and self-harm and point to the need for support schools and students as the repercussions of the pandemic continue. Yet, a systematic review found a reduction in service use by children and young people over the course of the pandemic [18]. It has been suggested that to prevent self-harm in children and young people, attention ought to be turned to issues that directly affect them such as bullying, mental health, family problems, and social media [19, 20]. However, as Borschmann and Kinner (2019) highlight, there is a lack of evidence documenting how effective interventions for this demographic would be [21].

Although determining prevalence is important in understanding and managing self-harm, it must be acknowledged that gaining accurate rates is inherently complex. To assess the difficulty of ascertaining prevalence rates, it is pertinent to consider the various streams of reporting and recording self-harm. First, some utilise statistics based on help-seeking via the GP. GP’s typically have a heavy workload and appointments are severely time limited [22]. Consequently, GP’s state that the screening tools for self-harm are too formal for a 10 min consultation, not allowing time for trust to be built between doctor and patient [23]. Secondly, hospital admissions have been used to discern self-harm rates. However, Hawton et al. [4] found that only 12.6% of the incidences of self-harm, reported by the 15–16 year old’s within their sample, required a visit to the hospital. Thirdly, one may rely on self-reported data, though Mars et al. [24] uncovered discrepancies within self-reported adolescent self-harm data, suggesting that prevalence approximations may underestimate the true rate. Lastly, research indicates that most children and young people who do seek help rely on informal streams of support [25, 26], in which case the self-harm may not be recorded at all. Evidently, gaining accurate prevalence rates requires extracting data from multiple sources.

Moreover, the existent literature demonstrates a variety of reasons why children and young people may choose not to report their self-harm, formally or informally. Those most in need of support for their suicidal ideation were the least likely to seek support [27]. For some young people, the belief that no external source can help or that the problem will resolve itself prevents them from seeking support [28, 29]. Other reasons included: not knowing who to confide in [26]; concerns about being placated with medication [30]; apprehensions around who to trust in terms of confidentiality, especially in rural areas [22]; and waiting times for seeing a health professional [22]. Biddle et al. [31] found that young men were less likely to seek support than young women, furthermore, the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Suicide and Self-Harm Prevention (APPGSS) [32] note that many struggle to access support, especially particular groups of young people such as those who identify as LGBTQ + , or those from an ethnic minority. Perhaps the most examined barrier to help-seeking, is the concern of stigmatisation.

Research has indicated that young people may not seek support out of fear of being labelled an ‘attention seeker’, by both peers and professionals [26, 33]. Utilising online tools, particularly anonymously, may enable those who are at-risk and not proactive in help-seeking to engage with some form of support system [34]. However, it has been suggested that the internet can normalise self-harm, with unrestricted access to gruesome imagery and new potential methods of harm [35]. The APPGSSP note that some worry they will be perceived as time wasters by health professionals as their injuries were self-inflicted, for some, this was based on their previous experiences of maltreatment [32]. Thus, the report recommends appropriate training for frontline staff, and a ‘buddy’ system within the NHS. Parker [36] found that the stigmatization of self-harming adolescents was perpetuated throughout schools through: word avoidance; topic avoidance; and negative judgmental behaviours. To combat these concerns around stigmatisation, the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCP) discouraged health professionals from recording self-harm in a judgemental manner and to ensure all professionals have the right training and supervision [37]. Bailey et al. [38] found that the type of- and reason for- self-harm is often absent from patient records. To facilitate a move towards accurate recordings of self-harm in adolescents, Bailey et al. [38] recommend that health care professionals discuss with patients what is being written on their medical records. Overall, compounded with the issues above around barriers to reporting, our ability to access and analyse accurate prevalence rates is immensely restricted as a consequence of this guidance not to record reports of self-harm. The RCP [37] noted the need for self-harm training for staff in schools, however, it has since been established that the limited funding and resources available to schools bounds the scope for the implementation of such training [39].

This systematic review was proposed to further explore the barriers and facilitators to reporting and recording self-harm in young people and to identify gaps that still need addressing in future research and practice.

Aim and objectives

The aim of this systematic review was to identify, explain and interpret the prominent or recurring themes relating to the barriers and facilitators of reporting and recording of self-harm in young people, across different settings, such as the healthcare setting, schools and the criminal justice setting.

This review sought to fulfil the following key primary objectives:

-

1.

To identify, explain and interpret the prominent or recurring themes relating to the barriers and facilitators of reporting and recording of self-harm in young people,

-

2.

To identify any gaps in the subject field in relation to young people reporting and recording self-harm,

-

3.

To use the findings to inform qualitative work with both young people who have self-harmed and relevant practitioners.

Methods

Due to anticipating the variable available evidence; the review was proposed as being best placed as a mixed-methods review. The SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research Type) [40] tool was used to encompass both quantitative and qualitative searches and to ensure thorough searches were carried out. Table 1 presents an example of the SPIDER search terms that were used. Developing specific inclusion and exclusion criteria, relevant to the review's aims and objectives, assisted in selecting papers.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Papers were eligible for inclusion in the systematic review if they presented barriers and facilitators to the reporting and the recording self-harm in young people. Self-harm, for the purpose of this review, was defined as "an act of self-injury or self-poisoning regardless of motivation or intent [41]”. The term reporting has been used to include the traditional concepts of help-seeking as any ‘any action or activity carried out by an adolescent who perceives herself/himself as needing personal, psychological, affective assistance or health or social services [42], whilst also including young people reporting their self-harm without the intention of receiving help to manage it. Recording has been used to include any method of documenting a young person’s self-harm, whether that it is in their medical notes, school files or within other social settings.

Papers were eligible if the population of interest was determined to be young people (males or females) aged 18 years and under. If any of the papers included a range of age groups (e.g., 12–20 years old), then they would only be eligible if the results relating to those aged 18 and under could be isolated. Any setting in which self-harm can be reported and recorded was acceptable for inclusion in the review. Therefore, it was anticipated that the review would include a range of settings and practitioners including schools, GP surgeries, hospitals, criminal justice settings etc. Both quantitative and qualitative and published and non-published literature were eligible for inclusion in the review, where relevant.

Exclusion criteria

Papers were not excluded by study design, location or language and any non-English papers were translated to assess relevance. Papers were excluded if self-harm could not be isolated from other behaviours and if young people were aged over 18 years. Studies published prior to 2004 were excluded as 2004 was the year self-harm was embedded into NICE guidelines and hence it is likely self-harm would have been recorded or reported differently within the literature [41].

Search strategy

The search strategy was broad in order to capture all types of barriers and facilitators to the reporting or recording of self-harm in young people. Keywords were coupled with relevant MeSH/ thesaurus terms and truncated as appropriate. The following databases were searched: MedLine, PsycINFO, EMBASE, CINAHL, SCOPUS and the Cochrane Library. Studies published in any language, from any country were included from 2004 to the current day.

Grey literature was also searched. Searches were conducted on online platforms such as Google, Google Scholar, MedNar, opengrey.au and databases of conference proceedings. For Google, the first 10 pages of results were looked at to ensure the specificity of results returned and to avoid sifting through irrelevant material. In addition, relevant specialist websites were searched for potentially relevant literature including: Gov.uk, NSPCC, Barnardo’s, Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Study selection

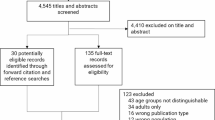

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analysis (PRISMA) flowchart (see Fig. 1) [43] was used as a guide and hence this review will be reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement [43, 44]. All search results, following the completion of the literature searches, across all six databases, were exported and managed in a newly created EndNote library. The first step was to remove any duplicate papers. Next, all of the titles and abstracts were screened against the review’s inclusion criteria by JF. For consistency, a second reviewer (DNB) double checked 20% of the search results, in order to determine whether decisions in relation to inclusion or exclusion matched. Any disagreements were recorded and resolved through team discussion. For the studies, that met the inclusion criteria, following the completion of the title and abstract screening, full text copies of the articles were retrieved for further exploration. These were then read and taken through to data extraction, if still appeared relevant. All full text articles were checked by two reviewers independently (GW and JF), and any disagreements were resolved by bringing in a third reviewer (DNB).

Data extraction and management

An Excel data extraction sheet was developed to extract relevant information from the included papers. To retain the focus of the paper and to avoid extracting irrelevant results, the extraction sheet was based around the following headings: Study, Country, Aim of Study, Type of Study, Participants, Setting, Facilitators to Reporting/ Recording and Barriers to Reporting/ Recording. For consistency, one researcher completed the data extraction (GW) and then a second team member (PA) went over the extraction sheet, to ensure no important findings had been missed or overlooked.

Risk of bias (quality) assessment

To assess the quality of the included studies, the relevant Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) quality assessment checklists were used [45]. The CASP checklists determine whether the results of a paper are valid, what are the results and whether the results help locally by asking a series of questions around the risk of bias [45]. The purpose of using the CASP criteria was to assess paper quality, and hence it was not used to contribute to decisions about whether to include studies. Two reviewers independently applied the CASP criteria to the included studies (GW and PA), and any disagreements were recorded and resolved through discussion. High risk of bias was recorded if ‘no’ or ‘unsure’ were recorded for 6 or more of the 11 questions on the tool. Medium risk of bias was assigned if ‘no’ or ‘unsure’ were recorded for 4–5 questions and Low risk for 1–3 questions.

Data synthesis

As it was anticipated that there would be a plethora of different study designs, the proposed synthesis was a narrative synthesis, which employed a thematic analysis. A narrative synthesis was used to ensure that all study types could be included in the review. The thematic synthesis was conducted to establish recurring and unique content across the studies that could be arranged into themes across the reporting and recording of self-harm. The thematic synthesis involved two reviewers coding the extracted data, identifying key themes, and categorising the themes that were established within facilitators or barriers of reporting or recording [46]. The key themes were then written up and presented as a narrative synthesis which all reviewers contributed to.

Results

The literature searches were undertaken in November 2021. The initial database searches revealed 17,234 papers, with searches of the grey literature sources not yielding any additional results. After completing the first sift; 138 papers were taken into the full text screening phase. All the full text papers were obtained, and then following the second sift, 19 papers were deemed eligible for inclusion in the final review. Figure 1 shows a PRISMA Diagram which depicts the flow of information through the different phases of the review.

Nineteen papers were deemed eligible for inclusion. Ten papers were quantitative studies, using surveys or Delphi methodology [25, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. Seven papers were qualitative studies employing interviews or focus group methods [56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. One paper used mixed methods [63] and one paper was an editorial [23]. All papers were from high-income countries, with 8 studies being conducted within the UK, 3 within the US, 3 in Australia, 2 in Ireland, 1 in Finland, 1 in Norway and 1 in Canada. The included papers were based in four main settings: healthcare settings, schools, a criminal justice setting and online settings. Therefore, the extraction tables (Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5) were grouped by setting, to allow key factors and themes from each setting and the different providers to be realised. Table 2 consists of the seven papers focusing on exploring the factors affecting the reporting or recording self-harm within a healthcare setting, such as a hospital or a GP [23, 47,48,49, 56, 57, 62, 63]. Table 3 includes the nine papers based in a school setting [25, 50,51,52,53,54, 58,59,60]. Table 4 has one paper which was based in a criminal justice setting; a youth offending team [61]. The final table, Table 5, presents one paper which was focused around young people accessing online support and therefore encompassed a range of different providers, populations etc. [55]. The results of the quality assessment have been included in each of these tables.

Main findings

As mentioned, the thematic synthesis of the 19 included studies was considered from two perspectives: reporting and recording of self-harm. The resulting themes have been presented in Table 6

As in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, the results are presented by facilitators and barriers to reporting and recording, under the four settings included in the existing literature. These are as anticipated: healthcare settings [23, 47,48,49, 56, 57, 62, 63], school settings [25, 50,51,52,53,54, 58,59,60], criminal justice settings [61] and an online setting [55].

Results—Healthcare setting

Eight papers demonstrated findings around the reporting and recording of self-harm in the healthcare setting [23, 47,48,49, 56, 57, 62, 63]. Bailey et al., is an editorial focusing on the challenges for general practice around self-harm in young people [23]. Bellairs- Walsh et al. explored young people's views and experiences related to the identification, assessment and care of suicidal behaviour and self-harm in primary care settings with GPs [57]. Fisher and Foster, looked at developing an evidence-based care plan/ pathway for children and young people in paediatric inpatient settings presenting with self-harm or suicidal behaviour [63]. Hawton et al., compared the characteristics of young people who reported deliberate self-harm episodes and presented at a hospital with those not attending hospital [47]. Jennings and Evans, explored the young person self-harm management and prevention practices, following reports that multi-agency teams were not effectively operating [56]. Saini et al., used Delphi methodology to reach consensus between different stakeholders and researchers on research priorities in suicide and self-harm to develop regional self-harm and suicide prevention and reduction schemes [48]. Miettinen et al. used different sources, such as an online forum to recruit young people to provide essays describing their experiences of healthcare related to self-harm in adolescence [62].The final paper by Tørmoen et al., sought to examine the use of child and adolescent psychiatric services (CAPS) by young people with both suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-harm, and to assess the psychosocial variables that characterised the young people [49].

Reporting facilitators

Facilitators to reporting self-harm across healthcare settings included recognising self-harm behaviours, training and experience, positive communication, individualised care, and safe information sharing. GPs being able to recognise behaviour when presented and initiating conversations around a young person’s self-harm, rather than the onus being on the young person, was seen as advantageous [57, 63]. Staff having a good knowledge and understanding around self-harm was seen as a reporting facilitator [63]. Although it was cited as being important to have received adequate training around self-harm [48], it was deemed to be more useful for clinicians to learn from their experiences of working with young people and understanding why they sought help [48, 56].

It was seen as imperative for young people to feel listened to, with an open dialogue [57], where they were given the opportunity to talk about their self-harm in their own words [23]. GPs using inviting and warm language, whilst demonstrating active listening with attentive body-language and good eye-contact were seen as facilitators [57]. In addition, young people valued being treated as an individual with GPs listening to young people’s concerns, preferences and offering them support as an individual. [56]. This was enhanced by clinicians informing young people around the outcomes of sharing information, in order to ensure that they felt comfortable and safe [57].

Reporting barriers

Barriers to reporting self-harm across healthcare settings included confidentiality concerns, negative perceptions of young people, communication difficulties, stigma and practical issues. Several studies found young people were often worried about reporting their self-harm to healthcare staff due to confidentiality and concerns around whether their information would be shared [23, 57]. This was compounded by young people experiencing poor mental health literacy and feeling hopeless and like they were a burden [57].

Poor communication was identified as being a barrier to reporting self-harm. Young people viewed the language, used by healthcare staff, around risk as problematic, ‘negative’ and ‘intimidating' [49], which is in line with other existing literature [26, 33]. In addition, GPs were viewed negatively if they appeared impersonal or indifferent towards young people. The language used by GPs was important in ensuring a young person felt they could report their self-harm and if it was not pitched appropriately, it could lead to missed opportunities for intervention [57]. Young people, who were self-harming, commonly had complex lives, with wider, confounding factors in play such as eating disorders and substance use and these were often underestimated [49, 56].

A prevalent theme emerged around stigma and perceptions; young people were reported as worried about not being taken seriously if they reported self-harm [23] and being concerned about the negative stigma associated with being labelled as a ‘self-harmer’ [48]. This was confirmed by findings in Fisher and Foster that reported young people who self-harmed were often labelled as ‘disruptive’, ‘demanding’, ‘aggressive’, and ‘difficult to understand and communicate with’ when presenting at hospital [63]. There were also negative perceptions of young people who self-harmed from specifically a care setting, reported in Jennings and Evans [56]. In the study by Miettinen et al. young people reported being unsure and uncertain about reporting their self-harm [62]. Young people felt anxious about their self-harm not being taken seriously and that they would ‘burden their loved ones’ [62]. Parents were also seen as a barrier for young people reporting self-harm. Often parents were unsupportive and reluctant about a young person reporting self-harm due to the negative connotations associated with a young person accessing psychiatric treatment [62]. Practical barriers to reporting self-harm included young people having to wait long periods of time for face-to-face appointments and the threshold to seek help was high as young people often required many GP visits and multiple referrals to access treatment [62].

Practical barriers to reporting self-harm across healthcare settings included too short appointments [23], ineffective screening tools that were not fit for purpose [23], hospitals as inappropriate settings for disclosing self-harm (chaotic, noisy etc.) [63] and non-individualised approaches hindering disclosure [56]. Within the hospital setting, nurses from the study by Fisher and Foster, expressed the desire for additional training to build knowledge as they reported feeling fearful of exacerbating young people’s problems [63].

Recording facilitators

There were fewer facilitators and barriers to recording self-harm in a healthcare setting extracted from the included papers. Facilitators were around being open to discussing what is recorded and services working together. Bailey et al. reported the importance of being able to discuss what was recorded in regards to a young person’s self-harm on their health records [23]. Talking to the young person about what was being recorded and for the staff recording it to be fully trained, was found to improve the consistency of recording [23]. In addition, Saini et al. highlighted the importance of different settings such as those within primary care GP and hospitals, schools and community services being able to communicate and work together when recording self-harm [48].

Recording barriers

The barriers to recording self-harm in a healthcare setting were mainly around stigma and the information being recorded. Often young people were found to be wary about the information around their self-harm being recorded and what information was shared and with whom due to the connotations of blame and associated stigma [23, 57].

The young people, involved in the study by Miettinen et al., reported that their self-harm was often ignored or professionals being unable to appropriately record self-harm and start the referral process [62]. In the study young people reported that their visible self-harm injuries were ignored and were not being recorded, despite them being asked about what they were [62]. This was compounded by staff not knowing what to record in relation to a young person’s self-harm and then not reacting after having seen visible injuries [62].

Results—School setting

The setting where the most literature was found, with regards to the reporting and recording of self-harm in young people, was the school setting, where nine papers were included in the survey [25, 50,51,52,53,54, 58,59,60]. Most papers were around the willingness of young people to talk to school staff about their self-harm or how school staff reported or recorded self-harm and their attitudes around it. Berger et al. 2014, looked to validate a measure of attitudes towards Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and examine the knowledge, attitudes, and confidence of school staff towards NSSI [50]. Dowling and Doyle, explored post-primary school guidance counsellors’ and teachers’ experiences of, and responses to, self-harm among students [58]. Evans et al. looked to ascertain whether young people who deliberately harmed themselves or had thoughts of self-harm differed from other young people in terms of help-seeking, communication and coping strategies [25]. Evans et al. sought to understand the school context, including existing provision, barriers to implementation, and acceptability of different approaches [51]. Heath et al. examined young people’s reports of willingness to access school-based support for NSSI [52]. Nearchou et al., determined the predictors of help-seeking intentions for symptoms of depression/ anxiety and self-harm in young people [53]. Roberts- Dobie and Donatelle, sought to examine the experience, knowledge and needs of school counsellors in relation to students' self-injurious behaviours [54]. Roberts et al. aimed to develop existing knowledge by investigating professional experiences and practices of school counsellors who work with young people who self-harm [59]. Finally Tillman et al., sought to understand the lived experiences of middle school girls who have engaged in NSSI and who have received professional help [60].

Reporting facilitators

Facilitators to reporting self-harm in young people, within the school setting, were staff being educated and knowledgeable, being able to make a young person feel comfortable, exploring different ways of disclosure and ensuring that staff well-being was also considered.

Multiple studies reported the importance of school staff being educated and knowledgeable around self-harm [51, 54, 58, 59]. More specifically, it was found to be advantageous to ensure the full spectrum of individuals, around a young person who is self-harming, to be educated, from teachers, counsellors, school nurses and other young people, parents etc. as they could all potentially be involved in reporting [54]. This also links with the finding around ensuring a co-ordinated approach was adopted, as joined up working helped to maintain consistent co-operation from different professionals [54, 59].

There was a plethora of results around who was the most appropriate member of staff for young people to report their self-harm to [25, 54, 58]. Roberts- Dobie reported that counsellors deemed themselves to be the most appropriate contact [54]. However, different members of staff being able to identify self-harm, in order to initiate conversations with young people, was seen as a facilitator to reporting. This included staff noticing subtle behaviour changes in a young person or being told about their self-harm by another young person, their friends or family Dowling et al. also reported the disclosure of self-harm could be via different subject teachers, with examples including English teachers identifying a young person’s self-harm via an emotive essay, or a Physical Education teacher noticing a young person’s refusal to change or wearing bandages to hide their injuries [58], rather than a defined member of staff being responsible for self-harm. Similar to the results from the healthcare setting it was seen as a facilitator for school staff to be open, non-judgemental and helpful [50, 60] and to ensure young people felt listened to [60].

Finally Dowling et al. reported the importance of school staff to have a way to debrief after difficult conversations with young people around their self-harm [58]. Staff found conversations less traumatic if they did not know a young person well, as they found it easier to maintain distance [58]. Self-care strategies, such as leaning on families, colleagues and friends and activities outside of work, also facilitated the maintenance of staff wellbeing [59].

Reporting barriers

Common barriers emerging from the included papers, within the school setting, were staff having a lack of knowledge around self-harm, a lack of time, money and resources, young people feeling uncomfortable with disclosing self-harm.

School staff commonly exhibited a lack of knowledge and confidence to help young people [50, 54, 58] and training was deemed to not be adequate [51, 58]. Dowling and Doyle reported that often school staff found self-harm difficult to identify, due to its hidden nature [58]. This was supported by Berger et al., which reported there was a need for helping young people to report their own or their peers’ self-harm [50]. There were role conflicts reported within some school staff, as some expressed being unwilling to participate in self-harm training as it made them feel uncomfortable and that it was not part of their role [59].

School staff were reported as feeling ‘panicked’ by self-harm reporting, but this reduced with experience [58]. Staff continuously faced concerns with larger class sizes and fewer yet busier teachers [58] with limited time and resources [51] and increasingly busy counsellors with heavier workloads [54]. This had a knock-on effect, resulting in less time for school staff to report self-harm.

Young people also felt reluctant and less comfortable reporting their self-harm to school staff [25, 60] and struggled with opening up and being honest, due to feeling like their concerns would be dismissed [60]. The reporting of self-harm was seen to be affected by a young person’s beliefs about other people's stigma towards self-harm and appeared to be a stronger predictor of help-seeking intentions than their own stigma beliefs [53]. This was exacerbated by school staff describing self-harm as ‘difficult’, ‘horrible’, and ‘disturbing’ in the study by Dowling and Doyle and the school staff were reported as being frustrated and less tolerant of young people perceived to be advantaged, with some staff considering self-harm behaviour to be ‘attention seeking’.

Age and gender differences were observed in regard to reporting. Heath et al. and Nearchou et al. which found younger school students, such as middle school students were more willing to report their self-harm and access school-based support than high school students [52, 54]. Nearchou et al. also found boys were more likely to report self-harm than girls [53]. Finally, money was cited as a barrier to disclosing or reporting self-harm, especially in countries such as the United States, as a young person was cited as being reluctant to report their self-harm due to not having health-insurance [60].

Recording facilitators

Again, there were fewer results focusing on the facilitators and barriers to recording self-harm. The facilitators that were identified were around age and co-ordinated help. Berger et al. reported that younger school staff were more knowledgeable and had higher self-perceived knowledge of NSSI than older colleagues [50]. This facilitated recording as they felt more comfortable doing so. Roberts et al. reported the importance of help recording a young person’s self-harm. Enlisting help to make referrals was found to be important and meant the process was more effective [59].

Recording barriers

The barriers to recording were around the length of professional experience and sex. Berger et al. reported the length of professional experience was negatively related to ability to identify NSSI, suggesting senior staff had poorer knowledge [50]. Staff who were more experienced with young people and NSSI were more confident and had higher self-perceived knowledge, understanding and more positive attitudes towards NSSI [50]. Therefore, suggesting a lack of experience responding to self-harm or an increased length of professional experience, were barriers to recording self-harm. The study also reported that females posed a greater confidence and knowledge of NSSI in comparison to males [50].

Results—Criminal justice setting

Knowles et al. [61] looked at the staff attitudes, within a Youth Offending Team (YOT), around screening for self-harm in young offenders to identify potential barriers when referring young people to specialist services.

Reporting facilitators

Within the study by Knowles et al., there was only a focus around the facilitators and barriers to reporting self-harm by the YOT staff [61]. A facilitator was having the option to access passive screening. Having a self-harm screening process, that did not rely on the willingness of staff to perform screening, was seen as beneficial to reporting self-harm [61]. On an organisational level and similar to other settings, it was seen as important to have a co-ordinated effort from the individual to an organisational level to remove the barriers to screening [61].

Reporting barriers

Barriers to reporting self-harm included staff not feeling qualified or that it was not part of their role, time and difficulties making referrals [61]. Staff within the YOT often did not feel comfortable talking about self-harm with young people [61]. This was put down to staff feeling like they did not have the knowledge or experience with self-harm, not knowing how to help and it not feeling a part of their role. In addition some staff were not keen to engage with mental health services or they lacked the capacity or time to be able to do so [61].

Results—Online setting

Frost et al. set out to investigate the perspectives of young people who self-injure regarding online services, with the aim of informing online service delivery, using a questionnaire [55]. It concentrates on young people who sought help for self-harm online, in order to determine their help-seeking preferences.

Reporting facilitators

Frost et al. found that using the internet was a facilitator to young people reporting self-harm [55]. Young people were reported as preferring to use the internet for help, over reporting their self-harm to someone in person [55]. This was amplified by their use of smartphones, and as the vast majority of young people included in the survey had a smartphone, they expressed wanting to access help using their phone [55]. Another key facilitator to reporting self-harm, and as reported in other settings was privacy [55]. Young people felt online sources were more private and would allow them to be freer to share their experiences.

Discussion

Addressing the aim and the objectives of this systematic review; the findings will be able to support ongoing research and inform qualitative work with both young people who have self-harmed, their parents and the relevant practitioners. Across the different settings there were key themes that emerged around the reporting and recording of self-harm in young people, and these could be unpacked to identify both facilitators and barriers.

The theme of negative perceptions and stigma, associated with young people reporting their self-harm continued to be prevalent across the included papers. This is not a novel observation of this review, but a finding that has appeared consistently in the literature [64,65,66] and reviews of the evidence [67]. The negative perceptions associated with self-harm were seen as a significant barrier to both the reporting and recording self-harm as young people often felt anxious about what was being recorded and therefore felt uncomfortable reporting their self-harm [48]. It was seen as advantageous for staff to use positive communication techniques and warm, inviting language to facilitate reporting [57]. By ensuring honest and open conversations take place around self-harm and encouraging practitioners to raise topics, without young people needing to themselves, it would likely contribute to increased conversations and referral to treatment of self-harm [57]. Initiatives and campaigns, examples including ‘Self- injury awareness month’ annually in March [68], and Mind’s ‘Time to Talk’ [69] around mental health, can also be seen as tools for encouraging conversations around self-harm. Widespread coverage around self-harm can contribute to addressing the stigma and taboo associated with it and can ensure that standard and consistent messaging around self-harm is cultivated.

Another key theme was around the training, education and knowledge of different providers. Although this varied across the different settings and level of experience, it was evident that more still needs to be done to ensure all staff working with young people have the right tools to support them with reporting or recording self-harm [51, 54, 58, 59]. There appeared to be less focus around recording self-harm in the included studies, with most of the findings around recording being barriers, such as staff being unable or unwilling to record self-harm. Therefore, this suggests that individuals who work with young people who may be self-harming, should receive more comprehensive guidance and support around how to effectively record self-harm to ensure young people can be referred to the appropriate support services and that a standard approach to recording and referring is maintained. This could include system wide use of passive screening techniques, such as techniques that do not rely on the willingness of staff to perform screening for self-harm to prompt reporting, as referenced with the criminal justice setting [61].

Specifically within the criminal justice setting there appeared to be a conflicted role identity about it ‘not being part of the YOT workers role’ [61]. The focus should be on adopting a person-centred approach and moving away from the need to stick to defined roles when working with young people. This is especially fundamental when considering young people who self-harm, as often they can have stressful lifestyles, with a myriad of challenges, that affect all aspects of their life, including their education, relationships and behaviour [23]. Therefore, it would likely be beneficial for the full spectrum of staff and practitioners, working with young people, to be able to engage in conversations around self-harm [49, 56]. Future practice should also be centred upon organisations working together and communicating as this was a facilitator for both reporting and recording self-harm [48].

Language use was a key finding, and there was evidence around how important it was in ensuring that the language used around self-harm was appropriate, and how self-harm was talked about in conversations with young people [57]. Interestingly, there was no findings identified around the use of gender specific language and gender identity within the included studies. There was no exploration around how using more gender inclusive language, such as gender-neutral language, may facilitate conversations with young people, even though LGBTQ + young people have higher rates of self-harm and suicide than their cisgender, heterosexual peers [70]. Therefore, this indicates another valuable avenue for future study.

Practical barriers included the lack of time, money and resources [63] which remain problematic in the majority of current service provision. However, the internet and online services offered a way for young people to share information about their self-harm in a more private, controlled way with less input from professionals [55]. Therefore, future work should continue to tap into online support and ways to increase online provision further as smartphones and online technology continue to be a way of effectively communicating with young people, especially in a post COVID-19 pandemic world.

Conclusion

From the systematic review of the current evidence, it was apparent that there is still progress to be made to improve the reporting and recording of self-harm in young people, across the different settings. Future work should concentrate on developing and implementing the facilitators including positive communication, joined up working approaches and exploring novel ways of reporting/ recording which engage young people, whilst aiming to ameliorate the barriers, such as the poor staff knowledge, stigma of self-harm and reducing concerns around information sharing. The findings of this review will also be able to support two ongoing research projects; (i) ‘Your Voice Heard’ where results from this study will be used to shape and inform the qualitative work with both young people who have self-harmed, their parents and the relevant practitioners, with the aim to provide recommendations for future practice, and (ii) the ADPH self-harm project, which is exploring case studies around young people who self-harm and giving a voice to school staff around current self-harm processes and procedures. For more information on either research project, please contact the corresponding author.

Availability of data and materials

All data analysed during this review are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ADPH:

-

Association of Directors of Public Health

- APPGSS:

-

All-Party Parliamentary Group on Suicide and Self-Harm Prevention

- ASCA:

-

American School Counselor Association

- CAPS:

-

Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Services

- CASP:

-

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- DSH:

-

Deliberate Self-Harm

- GP:

-

General Practice

- IPA:

-

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- MH:

-

Mental Health

- NSSH:

-

Non-Suicidal Self-Harm

- NSSI:

-

Non-Suicidal Self-Injury

- PE:

-

Physical Education

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analysis

- PHE:

-

Public Health England

- RCP:

-

Royal College of Psychiatrists

- SH:

-

Self-Harm

- SPIDER:

-

Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research Type

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- US:

-

United States

- YOT:

-

Youth Offending Team

- YP:

-

Young People

References

Royal College of Psychiatrists. Self-harm in Young People: For parents and carers. Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/parents-and-young-people/information-for-parents-and-carers/self-harm-in-young-people-for-parents-and-carers. Accessed 10/06/22.

Office for Health Improvement & Disparities, Fingertips Public Health Data: Children and Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing. Available from: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile-group/mental-health/profile/cypmh/data#page/1. Accessed 04/06/22

Bresin K, Schoenleber M. Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;38:55–64.

Hawton K, Rodham K, Evans E, Weatherall R. Deliberate self harm in adolescents: self report survey in schools in England. BMJ. 2002;325(7374):1207–11.

McManus S, Gunnell D, Cooper C, Bebbington PE, Howard LM, Brugha T, et al. Prevalence of non-suicidal self-harm and service contact in England, 2000–14: repeated cross-sectional surveys of the general population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):573–81.

Carr MJ, Ashcroft DM, Kontopantelis E, Awenat Y, Cooper J, Chew-Graham C, et al. The epidemiology of self-harm in a UK-wide primary care patient cohort, 2001–2013. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):1–10.

Geulayov G, Kapur N, Turnbull P, Clements C, Waters K, Ness J, et al. Epidemiology and trends in non-fatal self-harm in three centres in England, 2000–2012: findings from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010538.

Cooper J, Steeg S, Bennewith O, Lowe M, Gunnell D, House A, et al. Are hospital services for self-harm getting better? An observational study examining management, service provision and temporal trends in England. BMJ Open. 2013;3(11):e003444.

Polling C, Bakolis I, Hotopf M, Hatch SL. Differences in hospital admissions practices following self-harm and their influence on population-level comparisons of self-harm rates in South London: an observational study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e032906.

Al-Sharifi A, Krynicki CR, Upthegrove R. Self-harm and ethnicity: A systematic review. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2015;61(6):600–12.

Cooper J, Murphy E, Webb R, Hawton K, Bergen H, Waters K, et al. Ethnic differences in self-harm, rates, characteristics and service provision: three-city cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(3):212–8.

Diggins E, Kelley R, Cottrell D, House A, Owens D. Age-related differences in self-harm presentations and subsequent management of adolescents and young adults at the emergency department. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:399–405.

Cybulski L, Ashcroft DM, Carr MJ, Garg S, Chew-Graham CA, Kapur N, Webb RT. Temporal trends in annual incidence rates for psychiatric disorders and self-harm among children and adolescents in the UK, 2003–2018. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:229.

Morgan C, Webb RT, Carr MJ, Kontopantelis E, Green J, Chew-Graham CA, Kapur N, Ashcroft DM. Incidence, clinical management, and mortality risk following self harm among children and adolescents: Cohort study in primary care. BMJ. 2017;359:j4351.

McManus S, Gunnell D, Cooper C, Bebbington PE, Howard LM, Brugha T, Jenkins R, Hassiotis A, Weich S, Appleby L. Prevalence of non-suicidal self-harm and service contact in England, 2000–14: Repeated cross-sectional surveys of the general population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):573–81.

Hawton K, Rodham K, Evans E. By their own young hand: Deliberate self-harm and suicidal ideas in adolescents: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2006.

Geulayov G, Mansfield K, Jindra C, Hawton K, Fazel M. Loneliness and self-harm in adolescents during the first national COVID-19 lockdown: Results from a survey of 10,000 school pupils in England. Curr Psychol. 2022;Sep 15:1–2.

Wan MohdYunus WMA, Kauhanen L, Sourander A. Registered psychiatric service use, self-harm, and suicides of children and young people aged 0–24 before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Mental Health. 2022;16:15.

Fisher HL, Moffit TE, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Arseneault L, Caspi A. Bullying victimisation and risk of self harm in early adolescence: Longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e2683.

Padmanathan P, Biddle L, Carrol R, Derges J, Potokar J, Gunnell D. Suicide and self-harm related internet use: a cross sectional study and clinician focus groups. Crisis. 2018;36(9):469–78.

Borschmann R, Kinner SA. Responding to the rising prevalence of self-harm. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):548–9.

Mughal F, Troya MI, Dikomitis L, Chew-Graham CA, Babatunde OO. Role of the GP in the management of patients with self-harm behaviour: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(694):e364–73.

Bailey D, Wright N, Kemp L. Self-harm in young people: a challenge for general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67:542–3.

Mars B, Cornish R, Heron J, Boyd A, Crane C, Hawton K, et al. Using data linkage to investigate inconsistent reporting of self-harm and questionnaire non-response. Arch Suicide Res. 2016;20(2):113–41.

Evans E, Hawton K, Rodham K. In what ways are adolescents who engage in self-harm or experience thoughts of self-harm different in terms of help-seeking, communication and coping strategies? J Adolesc. 2005;28(4):573–87.

Fortune S, Sinclair J, Hawton K. Help-seeking before and after episodes of self-harm: a descriptive study in school pupils in England. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):1–13.

Carlton PA, Deane FP. Impact of attitudes and suicidal ideation on adolescents’ intentions to seek professional psychological help. J Adolesc. 2000;23(1):35–45.

Gould MS, Velting D, Kleinman M, Lucas C, Thomas JG, Chung M. Teenagers’ attitudes about coping strategies and help-seeking behavior for suicidality. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(9):1124–33.

Nada-Raja S, Morrison D, Skegg K. A population-based study of help-seeking for self-harm in young adults. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37(5):600–5.

Storey P, Hurry J, Jowitt S, Owens D, House A. Supporting young people who repeatedly self-harm. J R Soc Promot Health. 2005;125(2):71–5.

Biddle L, Gunnell D, Sharp D, Donovan JL. Factors influencing help seeking in mentally distressed young adults: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(501):248.

All-Party Parliamentary Group on Suicide and Self-Harm Prevention. Inquiry into the support available for young people who self-harm. 2020. Available at: https://media.samaritans.org/documents/Inquiry_into_the_support_available_for_young_people_who_self-harm.pdf. Accessed 10 June 21.

Lewis C, Ubido J, Timpson H. Case for Change: Self-harm in Children and Young People. November 2017. Available at https://www.ljmu.ac.uk/~/media/phi-reports/pdf/2018_01_case_for_change_self_harm_in_children_and_young_people.pdf. Accessed 10 June 21.

Record RA, Straub K, Stump N. #Selfharm on #Instagram: Examining user awareness and use of Instagram’s self-harm reporting tool. Health Commun. 2020;35(7):894–901.

Daine K, Hawton K, Singaravelu V, Stewart A, Simkin S, Montgomery P. The power of the web: a systematic review of studies of the influence of the internet on self-harm and suicide in young people. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77555.

Parker R. A small-scale study investigating staff and student perceptions of the barriers to a preventative approach for adolescent self-harm in secondary schools in Wales—A grounded theory model of stigma. Public Health. 2018;159:8–13.

Royal College of Psychiatrists. Managing Self-Harm in Young People CR192. Available from: https://www.proceduresonline.com/nesubregion/files/managing_self_harm.pdf. Accessed 10 June 21.

Bailey D, N. Wright, and L. Kemp. Summary Report for TASH (Talk About Self-Harm) Project – June 2015. Available at: http://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/27672/1/4081_Bailey.pdf. Accessed 11 June 21.

House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee. Children and Young People’s Mental Health. Eighth Report of Session 2021–2022. Available at https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/8153/documents/83622/default/. Accessed 10 June 21

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–43.

Rouski C, Knowles SF, Sellwood W, Hodge S. The quest for genuine care: a qualitative study of the experiences of young people who self-harm in residential care. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;26(2):418–29.

Rowe SL, French RS, Henderson C, Ougrin D, Slade M, Moran P. Help-seeking behaviour and adolescent self-harm: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(12):1083–95.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–41.

Critical Skills Appraisal Programme (CASP). CASP Checklists. Available at https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/. Accessed 16 Nov 21.

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320(7227):114–6.

Hawton K, Rodham K, Evans E, Harriss L. Adolescents who self harm: a comparison of those who go to hospital and those who do not. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2009;14(1):24–30.

Saini P, Clements C, Gardner KJ, Chopra J, Latham C, Kumar R, et al. Identifying suicide and self-harm research priorities in North West England: A Delphi study. Crisis. 2022;43(1):35.

Tørmoen AJ, Rossow I, Mork E, Mehlum L. Contact with child and adolescent psychiatric services among self-harming and suicidal adolescents in the general population: a cross sectional study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2014;8(1):1–8.

Berger E, Hasking P, Reupert A. “We’re working in the dark here”: Education needs of teachers and school staff regarding student self-injury. Sch Ment Heal. 2014;6(3):201–12.

Evans R, Parker R, Russell AE, Mathews F, Ford T, Hewitt G, et al. Adolescent self-harm prevention and intervention in secondary schools: A survey of staff in England and Wales. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2019;24(3):230–8.

Heath NL, Baxter AL, Toste JR, McLouth R. Adolescents’ willingness to access school-based support for nonsuicidal self-injury. Can J Sch Psychol. 2010;25(3):260–76.

Nearchou FA, Bird N, Costello A, Duggan S, Gilroy J, Long R, et al. Personal and perceived public mental-health stigma as predictors of help-seeking intentions in adolescents. J Adolesc. 2018;66:83–90.

Roberts-Dobie S, Donatelle RJ. School counselors and student self-injury. J Sch Health. 2007;77(5):257–64.

Frost M, Casey L, Rando N. Self-injury, help-seeking, and the Internet. Crisis. 2015;37(1):68–76.

Jennings S, Evans R. Inter-professional practice in the prevention and management of child and adolescent self-harm: foster carers’ and residential carers’ negotiation of expertise and professional identity. Sociol Health Illn. 2020;42(5):1024–40.

Bellairs-Walsh I, Perry Y, Krysinska K, Byrne SJ, Boland A, Michail M, et al. Best practice when working with suicidal behaviour and self-harm in primary care: a qualitative exploration of young people’s perspectives. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e038855.

Dowling S, Doyle L. Responding to self-harm in the school setting: the experience of guidance counsellors and teachers in Ireland. Br J Guid Couns. 2017;45(5):583–92.

Roberts EA. School counselors' professional experience and practices working with students who self-harm: a qualitative study. ProQuest LLC, Capella University; 2013.

Tillman KS, Prazak M, Obert ML. Understanding the experiences of middle school girls who have received help for non-suicidal self-injury. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;23(4):514–27.

Knowles SE, Townsend E, Anderson MP. Youth Justice staff attitudes towards screening for self-harm. Health Soc Care Community. 2012;20(5):506–15.

Miettinen TM, Kaunonen M, Kylmä J, Rissanen M-L, Aho AL. Experiences of help from the perspective of Finnish people who self-harmed during adolescence. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2021;42(10):917–28.

Fisher G, Foster C. Examining the needs of paediatric nurses caring for children and young people presenting with self-harm/suicidal behaviour on general paediatric wards: findings from a small-scale study. Child Care Pract. 2016;22(3):309–22.

Owens C, Hansford L, Sharkey S, Ford T. Needs and fears of young people presenting at accident and emergency department following an act of self-harm: secondary analysis of qualitative data. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(3):286–91.

Cleaver K, Meerabeau L, Maras P. Attitudes towards young people who self-harm: age, an influencing factor. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(12):2884–96.

Ferrey AE, Hughes ND, Simkin S, Locock L, Stewart A, Kapur N, et al. The impact of self-harm by young people on parents and families: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e009631.

McHale J, Felton A. Self-harm: what’s the problem? A literature review of the factors affecting attitudes towards self-harm. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010;17(8):732–40.

Serani D. March is self-injury awareness month: Supportive tips for non-suicidal self injury. Psychology Today. 2022. Available from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/two-takes-depression/202203/march-is-self-injury-awareness-month. Accessed 27 Apr 22.

Mind. Time to Talk Day 2022. Available from: https://www.mind.org.uk/get-involved/time-to-talk-day-2022/#:~:text=Time%20to%20Talk%20Day%20is,or%20colleagues%20about%20mental%20health. Accessed 27 Apr 22.

Williams AJ, Jones C, Arcelus J, Townsend E, Lazaridou A, Michail M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of victimisation and mental health prevalence among LGBTQ+ young people with experiences of self-harm and suicide. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245268.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The Your Voice Heard project has been funded by the National Institute for Health Research – Applied Research Collaboration, North East and North Cumbria (NIHR-ARC, NENC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JF, DNB and DS planned the project and constructed and refined the initial search strategy. JF ran all literature searches. JF, DNB and GW sifted all the search results. GW and FA completed the data extraction and quality assessment. Analysis and interpretation of the included papers’ data was completed by GW, with contributions from all authors. GW wrote the initial manuscript, but all authors (DNB, DS, EA, BJ, LC, FA and JF) were involved with the drafting and critical revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Waller, G., Newbury-Birch, D., Simpson, D. et al. The barriers and facilitators to the reporting and recording of self-harm in young people aged 18 and under: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 23, 158 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15046-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15046-7