Abstract

Background

No study appraised the knowledge gaps and factors impacting men’s sexual and reproductive health (SRH) in MENA (Middle East and North Africa). The current scoping review undertook this task.

Methods

We searched PubMed and Web of Science (WoS) electronic databases for original articles on men’s SRH published from MENA. Data was extracted from the selected articles and mapped out employing the WHO framework for operationalising SRH. Analyses and data synthesis identified the factors impacting on men’s experiences of and access to SRH.

Results

A total of 98 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. The majority of studies focused on HIV and other sexually transmissible infections (67%); followed by comprehensive education and information (10%); contraception counselling/provision (9%); sexual function and psychosexual counselling (5%); fertility care (8%); and gender-based violence prevention, support/care (1%). There were no studies on antenatal/intrapartum/postnatal care and on safe abortion care (0% for both). Conceptually, there was lack of knowledge of the different domains of men’s SRH, with negative attitudes, and many misconceptions; as well as a deficiency of health system policies, strategies and interventions for SRH.

Conclusion

Men’s SRH is not sufficiently prioritized. We observed five ‘paradoxes’: strong focus on HIV/AIDS, when MENA has low prevalence of HIV; weak focus on both fertility and sexual dysfunctions, despite their high prevalence in MENA; no publications on men’s involvement in sexual gender-based violence, despite its frequency across MENA; no studies of men’s involvement in antenatal/intrapartum/postnatal care, despite the international literature valuing such involvement; and, many studies identifying lack of SRH knowledge, but no publications on policies and strategies addressing such shortcoming. These ‘mismatches’ suggest the necessity for efforts to enhance the education of the general population and healthcare workers, as well as improvements across MENA health systems, with future research examining their effects on men’s SRH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Historically, sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and rights were viewed as a woman’s issue [1]. One of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals is ensuring universal access to SRH [2]. However, despite the growing recognition that men also need SRH care, they remain underrepresented in the SRH social debate, care, and research [3]. Interestingly, the impact of male SRH on men’s welfare was only considered as function of women’s SRH rights [4]. Generally, barriers to men’s engagement in SRH include the lack of health insurance, masculinity ideas that conflict with SRH care, stigma related to accessing services, and lack of knowledge regarding available services [5]. For instance, across high- and low-income countries, shortcomings of men’s SRH at the policy level, availability and accessibility of clinical services and acceptability by society are evident [2, 6]. The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is no exception.

The Reproductive Health Working Group established in 1988 in Cairo to advance research in the Arab countries and Turkey began with a focus on women [7]. With time, the focus widened to include men’s lives and their impact on women’s health [8]. Three decades later, the situation remains not much changed [9, 10]. Some Arab nations have attempted health system reforms recently, however further efforts are still needed to include SRH [11]. Challenges that appear to hinder the implementation of new strategies that facilitate research of SRH issues among men in MENA include attitudes of male dominancy, and traditional myths that led to stigma and biases when dealing with SRH. In addition, sociopolitical instabilities in MENA have resulted in one of the highest numbers and range of refugees/humanitarian settings globally, associated with collapsed health systems, lack of essential medications and contraceptives, as well as absence of and low access to skilled health care providers (HCP) [12].

Therefore, the current scoping review aimed to outline the knowledge gaps and considerations that impact on men regarding SRH in MENA. Specifically, we appraised the range of factors that bear on men’s SRH in terms of clients/users, healthcare providers (HCPs), healthcare system and sociopolitical environment.

Methods

Scoping review

The purpose of a scoping review is not to localize and account for every published information on the topic [13]. Rather, the goal is intentionally wider, to interrogate the literature, discover the important features of the topic, unearth potential gaps, display crucial examples and synthesize research evidence, particularly when the subject has not been meticulously reviewed or is complicated, heterogeneous and assorted [14,15,16]. Therefore, the scoping review was selected to appraise SRH care for men in MENA. The current scoping review was undertaken in line with The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews [17]. We employed a six-step framework in line with Arksey and O’Malley [18], with procedural and methodological rigor, and clarity/transparency relating to methodology (Table 1) [19,20,21]. Table 2 outlines the definitions used in this review. The search terms employed are depicted in a supplementary file (Supplementary Box 1). The inclusion criteria employed by the current review included: (1) peer-reviewed empirical studies, all designs were taken into account; (2) published between January 2010 and May 2020; and (3) appraising the experiences of men in SRHC or the healthcare providers’ (HCPs) perspectives on men’s SRHC; and (4) undertaken in the nations of the MENA region. Items that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded.

The review team systematically synthesized the findings and summarized and presented the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. This included extracting the aims, populations, findings and conclusions of each included study development of an excel sheet. Then groupings were created based on the eight domains of SRH as outlined by WHO [19] framework for operationalising sexual health and its linkages to reproductive health, and further inspired by the findings that were emerging. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus between the team members.

Theoretical frameworks

The theoretical framework for analysis we employed involved two interrelated schemes. The first is WHO’s (2017) framework for operationalising sexual health and its linkages to reproductive health, comprising 8 domains: antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care; comprehensive education and information; contraception counselling and provision; gender-based violence prevention, support and care; fertility care; prevention and control of HIV and other sexually transmissible infections (STIs); safe abortion care; sexual function and psychosexual counselling [19].

Then, for each of these domains, we further employed Kilbourne et al’s (2006) framework to outline the health service perspectives on the appreciation of health and healthcare disparities, highlighting the factors influencing men’s experiences, including: individual (HCPs and users); interpersonal (healthcare encounter and contact characteristics); organisational (healthcare system); and the larger influence of the community and public policies (sociopolitical). Our searches of men’s SRH yielded very sparse articles on healthcare encounter and contact characteristics, therefore our domains are organized under 3 categories, namely clients/ HCPs; healthcare system factors; and sociopolitical factors [22].

Results

Search results

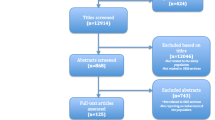

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow chart of the search results of men’s experiences in sexual and reproductive healthcare in MENA countries. After searching and screening, a total of 98 articles were finally included in the present review.

PRISMA flow chart on search results of men’s experiences in sexual and reproductive healthcare in MENA countries [23]

Men’s SRH topics were grouped using the WHO framework, illustrating the intertwined features between sexual health and reproductive health [1]. The great majority of studies focused on the prevention and control of HIV and other sexually transmissible infections (67%). Conversely, only 1 study (1%) discussed gender-based violence; and no studies attended to the two domains of antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care and safe abortion care (0% for both) (Fig. 2).

Description of identified studies in terms of WHO’s Framework [19]

Clients and populations

The identified studies included children/adolescents, youth, school/university students, HCPs, particular patient groups, general public or special populations e.g., industrial/tourist workers, refugees, truck drivers, refugees, seafarers, alcohol/drug abusers, men having sex with men and female/male sex workers, and people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) or healthy children/ adolescents of HIV-positive parents (Supplementary Table 1).

Comprehensive education and information

A total of 10% of the studies we identified were dedicated per se to comprehensive education. However, education was generally discussed in the greater majority of the articles that this review identified, focusing on discussions of the knowledge levels of different population groups towards several aspects of SRH in men, exploring the determinants of knowledge gaps among clients and HCPs, as well as health systems and sociopolitical factors (detailed below). Generally, these studies identified a knowledge lack regarding issues relating to men’s SRH in MENA.

Prevention and control of HIV and other sexually transmissible infections

Most studies of the review assessed the knowledge of a range of population groups pertaining to prevention and control of STIs and HIV/AIDS. More focus was directed towards knowledge level among clients/ users than of HCPs. Overall, there was low knowledge level across most of the groups that were assessed. Knowledge level was influenced by factors including age, sex, level of education and experience with age. Knowledge deficits often translated into negative attitudes towards HIV/AIDS or PLWHA. In addition, little is known about the perception of the magnitude of HIV/AIDS in MENA (Table 3).

In terms of the healthcare system, for HIV, much had been achieved in linking to and retention in care, antiretroviral therapy coverage and viral suppression, despite obstacles in prevention programs e.g., deficient funding and infection control due to lack in supplies and procedures as well as insufficient data/surveillance [58, 59]. The financial burden/ healthcare costs of PLWHA varied, depending on the presenting illness, clinical stage, developed opportunistic infection, co-morbidity, and pharmacological therapy [60], with empirical results illustrating a negative relationship between both public and private healthcare spending and HIV [61]. Policies and protocols regarding dealing with PLWHA were also absent [55]. In addition, war had restricted the surveillance activities e.g., access to voluntary counseling and treatment (VCT) centers in Syria [62]. Therefore, many opportunities for HIV testing, based on at-risk behaviors or clinical signs, were missed [63].

Several HIV awareness programs have been implemented. At hospital level, introduction of multi-disciplinary team (MDT) approach in managing HIV patients resulted in statistically significant control of the disease [64]. On the population level, school-based HIV education interventions exhibited mixed effectiveness in improving knowledge of HIV transmission/ prevention [24, 65, 66]. The key enabling factors were high quality of training for peer educators, supportive school principals, and parental acceptance of the intervention [67]. Community prevention in Sudan and Yemen was directed to the general public as well as to men who have sex with men (MSM) and female sex worker (FSW), focusing on behavioural change, enabling supportive environments and providing support for PLWHA [58]. Likewise, community-based educational interventions targeting truck drivers was effective in increasing coverage of HIV testing and counseling [68]. NGOs In Lebanon adopted HIV self-testing but uptake was low due to noncompliance of beneficiaries and lack of human/financial resources. Interestingly, self-testing was much improved during COVID-19 because of the absence of on-site activities, shifting more efforts towards HIV self-testing [69]. Generally, the apparent trend that this review observed was a deficiency of studies addressing the healthcare system and policies pertaining to the prevention and control of HIV and other STIs.

As for the social factors, high stigma and discrimination toward PLWHA were present [26, 39], rooted in values and fears, and manifesting in reluctance to use the same health facilities as PLWHA [70]. PLWHA faced such stigma in their homes and at work, forcing them to seek support from NGOs or close family. This stigma affected their disclosure to the wider community due to uncertainty of the repercussions, leading to a lonely life and financial difficulties [41]. In addition, HIV testing uptake was limited by concerns about confidentiality and fear of repercussions on health and employment [71]. Stigmatization of PLWHA was inversely related to HIV/AIDS knowledge [47, 72]. Stigma extended to physicians providing care for PLWHA, caused by fear of infection, to the extent of community unwillingness to use those physicians’ services. On the other hand, stigma toward physicians who refused to provide care was linked to perceptions of unethical behavior [70]. Victimization was also evident, e.g., most Saudi students believed that PLWHA were responsible for their infection and that AIDS was a Godly punishment [72]. Collectively, the apparent trend we observed in terms of the studies in this review was the generalized stigmatization of the PLWHA as well as in some cases the HCWs dealing with them.

Fertility care/ sexual function and psychosexual counselling

Some end-users displayed limited/inadequate knowledge about the concept, availability and benefits of SRH, voiced by the need for more information and quality services [73]. Healthcare workers sometimes exhibited deficient knowledge with regards to male SRH services [73,74,75,76]. This led to different personal attitudes towards the problem that was affected by age, sex and level of education [77] (Table 4). As for sexual health, although the knowledge level was acceptable, however, the sociopolitical norms affected the proper attitude towards the topic. This goes for general population as well as HCP (Table 4).

Healthcare system-related factors suggested that improvements in quality of infertility management required evidence-based training, supplies, laboratory/radiology support, improved communications with specialists, and availability of guidelines [77]. Youth also felt that SRH services needed to be easily accessible and have equal geographical distribution [73]. Reproductive tourism attracted patients from countries with deficient invitro fertilization (IVF) services or policy restrictions, and required high-tech medical settings, with visa regulations allowing users to complete an entire IVF cycle [89].

Contraception counselling and provision

The knowledge and acceptance of family planning varied across MENA. Generally, good awareness of contraceptive approaches was mainly for women’s methods but not for male contraception. However, such awareness was not translated into increased application/use of family planning in many MENA countries due to religious and sociocultural norms surrounding this topic. The lack of knowledge about male contraception was also including HCP e.g., pharmacists (Table 5).

Sex-based violence

Little information exists on gender-based violence in MENA, and our search yielded only 1 article. In Egypt, the majority of street children experienced more than one risk including harassment or abuse by police and other street children, drug abuse, and, among sexually active 15–17-year-olds, most reported multiple partners and never using condoms, and most girls had experienced sexual abuse [96]. Such behaviors put them in substantial overlap with populations at highest risk for HIV, namely men who have sex with men, commercial sex workers, and injection drug users [96].

Discussion

Addressing SRH of men alongside that of women’s is essential. However, it has not received the attention it deserves worldwide. We outlined the current knowledge, knowledge gaps and considerations that impact on men’s SRH in MENA, and appraised the HCPs’, users’, healthcare systems’ and social factors affecting such services. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive scoping review of men’s SRH in MENA.

Our main findings unearthed a strong HIV/AIDS focus of the published outputs, but a much weaker focus on issues related to fertility care, sexual dysfunctions/ counselling, and gender-based violence. The general population, different clientele groups, and a range of HCPs exhibited many SRH knowledge gaps, that subsequently lead to a high prevalence of unfavorable attitudes towards men’s SRH conditions, stigmatization, and the emergence of many misconceptions. Generally, across the range of countries under examination, the quality of SRH services could be improved. Surprisingly, we could not find published data on legislation, government policies or national SRH strategies. More importantly, we observed several paradoxes in terms of the lack of congruence between many of the domains that the published outputs addressed on the one hand; and the actual ‘on the ground’ situation across MENA on the other.

The first paradox pertained to the strong HIV/AIDS focus across the published literature, despite the low prevalence/ burden in MENA region (0.1%) [97, 98]. While it is difficult to speculate the reasons behind such discrepancy, perhaps it might be explained by the wide international interest and availability of funding to explore epidemiological and behavioural HIV/AIDS research, as evidenced by that most studies were funded by multi-lateral bodies e.g., UNICEF or philanthropic agencies [56, 67, 99]. Notwithstanding, war and political instabilities may increase the vulnerability of the region to HIV by reducing access to prevention services, destroying health care infrastructure, disrupting social support networks, increasing exposure to sexual violence, and expanding immigration and displacement [100]. Despite the tremendous efforts made in the global cognition and epidemiology of HIV infection, knowledge in MENA remains limited and controversial [99]. The large number of published papers on HIV/AIDS we observed concurs with the findings of a scoping review of men’s SRH in Nordic countries, where out of 68 studies that were identified, 15 papers dealt with STIs, mainly HIV (12 papers) and MSM (9 papers) [101].

The second paradox was the weak focus of the published articles on the two topics of fertility care and sexual dysfunctions/counselling, despite the high prevalence of fertility and sexual problems in MENA (22.6%) [102]. Such misfit might by due to the complex cultural, religious, community gender and social norms prevalent among MENA populations that render them reluctant to disclose their SRH concerns [80]. Likewise, MENA has low knowledge of sexual relationships, attributed to a lack of sex education in schools and the conservative culture of the community, factors that might contribute to the increasing prevalence of e.g., premature ejaculation in the region [103]. Similarly, erectile dysfunction (ED) is quite prevalent among Arab men, probably explained by the high prevalence of endothelial dysfunction risk [104]. Again, our findings support a review that scoped men’s SRH across Scandinavia, where sexual functioning/ counselling studies covered a very small proportion (2/68) of the studies that the review identified [101].

The third paradox we observed was related to gender-based violence. The current review found that publications of gender-based violence prevention, support and care represented only 2% of the retrieved studies. This is despite that women’s exposure to male domination has long been normalized in the Arab world [105, 106]. This could be due to possible gender disparity and male predominance in MENA representing barriers to such research [107]. Elsewhere, female researchers lag behind their male counterparts in successfully receiving grants [108]. Even though the prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) is high across Arab countries, evidence on its correlates remains limited [109]. The situation is complicated by the fact that the West’s social acceptance of divorce is not shared by Arab nations, where the centrality of marriage and family culture persists, and divorce continues to be stigmatized [109]. A scoping review of men’s SRH in the Nordic countries found that published studies about sexual violence comprised a very small minority (2/68) of the studies [101], concurring with our findings. Hence, efforts to mitigate gender gap and promote equity, diversity, and inclusion of females in research may improve any gender-based parity in research topics.

The fourth paradox was that the present review found no studies pertaining to men’s SRH that addressed the domain of antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care (0%), despite that men’s involvement in maternal health programs is a key to increase utilization of maternal health services [110]. This could be due to prohibition of gender mixing in antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care as well as in women’s hospital settings, hence disallowing male presence in such encounters. Such lack supports that in spite of the growing recognition of father’s importance for early family health/well-being, there has been very limited attention to men’s own experiences and developmental needs during their partner’s antenatal visits [111, 112]. Nevertheless, our observations contrasts with the Nordic study, where more than one-third of the papers were related to experiences of expectant fathers during antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care [101]. Empowering men with antenatal care knowledge and joint decision-making with their spouses increases male involvement [113], particularly that complex community sociocultural norms and social stigma are barriers to men’s attendance at antenatal care services with their partners [114]. The present maternity health policies in Arab countries might need revision to allow fathers’ inclusion [115]; and our findings suggest a need for communication, education, and information-based health promotion programs that empower men in these domains.

The fifth paradox was that a great proportion of studies discussed knowledge levels and gaps pertaining to men’s SRH in MENA, identifying a range of factors that influence knowledge. Surprisingly, there was no parallel body of literature debating effective interventions and their implementation in order to remedy/overcome such gaps. Similarly, we found no articles dedicated to policies and strategies to address such shortcomings at state, health care system and public health policy making level, when certainly improving men’s access to SRH requires state, health care system and health care providers interventions and policies [4, 101].

Likewise, the present review found no studies of men’s SRH that addressed safe abortion care (0%), not surprising given that abortion is illegal across most of the region, and there are various legal and societal barriers to the practice in the countries where it is allowed [116]. Very few publications exist on abortion in MENA, and those that do exist tend to give an overview of the legislation of different states or evaluate Islam’s position on abortion [117,118,119,120,121]. Detailed studies on actual medical practices, political debates, local legal implementation, moral/social norms, and trajectories of MENA women are very rare [122,123,124,125,126], let alone those on men’s participation in safe abortion care.

A unique characteristic across MENA is the prevalent political instabilities and refugee situations [44]. MENA has a current 16 million forcibly displaced and stateless people [127], situations that increase risky behavior for HIV and STIs [44]. Our findings resonate with Uganda, where refugee adolescents and displaced youth were a key population left behind in HIV prevention efforts [128]. Young refugees have limited access to sexual health information and resources in their resettlement places, highlighting a need for sexual health education programs for men and women as part of resettlement services [129]. Notwithstanding, Egypt has taken welcome steps: policies in progress include commitment to give refugees access to primary health care and education within national systems, and refugees are currently covered by the universal health care insurance scheme on equal footing with Egyptians [130].

The current scoping review has limitations. Surveys and reports about MENA health issues are mainly published in local languages and hardly accessible through electronic databases [102]. The study has many strengths. To our knowledge, this study is the first scoping review focusing on men’s experiences in SRH care across MENA. There was no time limitation for our literature search. In line with others [14, 15], the review was driven by a strict peer reviewed protocol. For an appropriate search, we examined the search strategy used in a similar published article on men’s SRH in Nordic countries [101] and modified the search terms they used. We searched four electronic bibliographic databases and reference lists of articles. Despite that our search was conducted using only English terms, our review included any articles published in English or Arabic; given that Arabic is the major language in MENA. The screening and data characterization forms that were employed were pretested by all members of the reviewer team and modified as appropriate before the review. Three training sessions included the completion of the screening and data characterization forms, using articles that were randomly selected from the literature. Data extraction of each article was undertaken by two independent members of the review team (WEA, MA) who worked simultaneously together on each article, and any disagreements were resolved by discussion. The review team systematically synthesized the findings by extracting the aims, populations, findings and conclusions of each included study and categorizing them based on the eight WHO SRH domains.

Conclusion

It is important for men to access SRH care. The available literature from the MENA region suggests that men’s SRH is not sufficiently prioritized. A detailed landscape of men’s experiences in SRH care across these countries remains to be explored. A number of pertinent ‘mismatches’ were evident in the literature. There was strong focus on HIV/AIDS, when MENA has the lowest prevalence of HIV in the world; a much weaker focus on fertility and sexual dysfunctions, despite that these conditions were much more prevalent in MENA countries; no publications on men’s involvement in sexual gender-based violence, despite women’s exposure to its various forms across the MENA region; and no studies pertaining to men’s SRH in terms of their involvement in antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care, despite the prevailing international literature to the value of such involvement. Such incongruencies might serve to provide future direction for the formulation and implementation of comprehensive strategies to help tackle men’s SRH challenges in MENA region. These could include strengthening the current policies, strategies and interventions to enhance and improve the attitudes, behaviors and education of the general public, the youth, men in general as well as HCPs. Furthermore, strengthening the health systems over time in terms of political commitment, structures, organization, funding and interventions to address core issues and to more formally respond to men’s SRH challenges in MENA would be welcomed. Future research should examine the influence of policies and the healthcare service delivery and organization on men’s access and experiences in SRH care.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Grandahl M, Bodin M, Stern J. In everybody’s interest but no one’s assigned responsibility: midwives’ thoughts and experiences of preventive work for men’s sexual and reproductive health and rights within primary care. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1423.

Report of the International Conference on Population and Development (Cairo, 5–13. September 1994). New York (NY): United Nations; 1994 available at https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_CONF.171_13.pdf. Accessed 1 July 2022.

Kalmuss D, Austrian K. Real men do... real men don’t: Young Latino and African American men’s discourses regarding sexual health care utilization. Am J Mens Health. 2010;4(3):218–30.

Makarow M, Hojgaard L. Male reproductive health: Its impacts in relation to general well-being and low European fertility rates. 2010. Retrieved from http://www.esf.org/fileadmin/Public_documents/Publications/SPB40_MaleReproductiveHealth.pdf.

Burns JC, Reeves J, Calvert WJ, Adams M, Ozuna-Harrison R, Smith MJ, Baranwal S, Johnson K, Rodgers CRR, Watkins DC. Engaging young black males in sexual and Reproductive Health Care: a review of the literature. Am J Mens Health. 2021;15(6):15579883211062024.

WHO Europe. Strategy on the health and well-being of men in the WHO European region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, Regional Committee for Europe; 2018.

DeJong J, Zurayk H, Myntti C, Tekçe B, Giacaman R, Bashour H, Ghérissi A, Gaballah N. Health research in a turbulent region: the Reproductive Health Working Group. Reprod Health Matters. 2017;25(sup1):4–15.

Ghannam F. Live and die like a man: gender dynamics in urban Egypt. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2013. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/. Accessed 19 Jan 2019

Abu-Rmeileh NME, Ghandour R, Tucktuck M, Obiedallah M. Research priority-setting: reproductive health in the occupied palestinian territory. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):27.

Shalash A, Alsalman HM, Hamed A, Abu Helo M, Ghandour R, Albarqouni L, Abu Rmeileh NM. The range and nature of reproductive health research in the occupied palestinian territory: a scoping review. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):41.

Kabakian-Khasholian T, Quezada-Yamamoto H, Ali A, Sahbani S, Afifi M, Rawaf S, El Rabbat M. Integration of sexual and reproductive health services in the provision of primary health care in the Arab States: status and a way forward. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020;28(2):1773693.

Inter-agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises. Inter-agency field manual on reproductive health in humanitarian settings: 2010 revision for field review. Inter-agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises; 2018. Available at https://iawg.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/IAFM-English.pdf. Accessed 29 June 2022.

El Ansari W, Elhag W. Weight regain and Insufficient Weight loss after bariatric surgery: definitions, prevalence, Mechanisms, Predictors, Prevention and Management Strategies, and knowledge Gaps-a scoping review. Obes Surg. 2021;31(4):1755–66.

El Ansari W, El-Ansari K. Missing something? A scoping review of venous thromboembolic events and their associations with bariatric surgery. Refining the evidence base. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;59:264–73.

El Ansari W, El-Ansari K. Missing something? Comparisons of effectiveness and outcomes of bariatric surgery procedures and their Preferred Reporting: Refining the evidence base. Obes Surg. 2020;30(8):3167–77.

Daudt HM, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:48.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MD, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2017 Sexual health and its linkages to reproductive health: an operational approach. WHO: Geneva, Switzerland. Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258738/9789241512886-eng.pdf;jsessionid=A20D089FFCBCA9F97264F98E57881DA1?sequence=1. Accessed 2 Mar 2022.

Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(10):1386–400.

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.

Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Megan Crowley-Matoka M, Fine MJ. Advancing Health Disparities Research within the Health Care System: a conceptual Framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2113–21.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Abolfotouh MA. The impact of a lecture on AIDS on knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of male school-age adolescents in the Asir Region of southwestern Saudi Arabia. J Community Health. 1995;20(3):271–81.

Alhasawi A, Grover SB, Sadek A, Ashoor I, Alkhabbaz I, Almasri S. Assessing HIV/AIDS knowledge, awareness, and attitudes among senior High School students in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2019;28(5):470–6.

Al-Iryani B, Raja’a YA, Kok G, Van Den Borne B. HIV knowledge and stigmatization among adolescents in yemeni schools. Int Q Community Health Educ 2009. 2010;30(4):311–20. – ( .

Boneberger A, Rückinger S, Guthold R, Kann L, Riley L. HIV/AIDS related knowledge among school-going adolescents from the Middle East and North Africa. Sex Health. 2012;9(2):196–8.

Jaffer YA, Afifi M, Al Ajmi F, Alouhaishi K. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of secondary-school pupils in Oman: II. Reproductive health. EMHJ. 2006;12(1–2):50–60.

Al-Jabri AA, Al-Abri JH. Knowledge and attitudes of undergraduate medical and non-medical students in Sultan Qaboos University toward acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Saudi Med J. 2003;24(3):273–7.

Al-Rabeei NA, Dallak AM, Al-Awadi FG. Knowledge, attitude and beliefs towards HIV/AIDS among students of health institutes in Sana’a city. EMHJ. 2012;18(3):221–6.

Al-Mazrou YY, Abouzeid MS, Al-Jeffri MH. Knowledge and attitudes of paramedical students in Saudi Arabia toward HIV/AIDS. Saudi Med J. 2005;26(8):1183–9.

Nasir EF, Astrøm AN, David J, Ali RW. HIV and AIDS related knowledge, sources of information, and reported need for further education among dental students in Sudan–a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:86.

Premadasa G, Sadek M, Ellepola A, Sreedharan J, Muttappallymyalil J. Knowledge of and attitudes towards HIV/AIDS: a survey among dental students in Ajman, UAE. J Investig Clin Dent. 2015;6(2):147–55.

Farsi NJ, Baharoon AH, Jiffri AE, Marzouki HZ, Merdad MA, Merdad LA. Human papillomavirus knowledge and vaccine acceptability among male medical students in Saudi Arabia. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(7):1968–74.

Farsi NJ, Al Sharif S, Al Qathmi M, Merdad M, Marzouki H, Merdad L. Knowledge of human papillomavirus (HPV) and Oropharyngeal Cancer and Acceptability of the HPV Vaccine among Dental Students. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;21(12):3595–603.

Alkhasawneh E, McFarland W, Mandel J, Seshan V. Insight into jordanian thinking about HIV: knowledge of jordanian men and women about HIV prevention. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25(1):e1–9.

Al-Ghanim SA. Exploring public knowledge and attitudes towards HIV/AIDS in Saudi Arabia. A survey of primary health care users. Saudi Med J. 2005;26(5):812–8.

al-Owaish R, Moussa MA, Anwar S, al-Shoumer H, Sharma P. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices about HIV/AIDS in Kuwait. AIDS Educ Prev. 1999;11(2):163–73.

Al-Serouri AW, Takioldin M, Oshish H, Aldobaibi A, Abdelmajed A. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about HIV/AIDS in Sana’a. Yemen EMHJ. 2002;8(6):706–15.

Alshehri AM, et al. The Awareness of the Human Papillomavirus Infection and Oropharyngeal Cancer in People to Improve the Health Care System at Al Qunfudhah Region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J Healthc Eng. 2021;2021:5185075.

Kulane A, Owuor JOA, Sematimba D, Abdulahi SA, Yusuf HM, Mohamed LM. Access to HIV Care and Resilience in a long-term conflict setting: a qualitative Assessment of the Experiences of living with diagnosed HIV in Mogadishu. Somali IJERPH. 2017;14(7):721.

Salama II, Kotb NK, Hemeda SA, Zaki F. HIV/AIDS knowledge and attitudes among alcohol and drug abusers in Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 1998;73(5–6):479–500.

Laraqui S, Laraqui O, Manar N, Ghailan T, Belabsir M, Deschamps F, Laraqui CH. The assessment of seafarers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices related to STI/HIV/AIDS in northern Morocco. Int Marit Health. 2017;68(1):26–30.

Holt BY, Effler P, Brady W, Friday J, Belay E, Parker K, Toole M. Planning STI/HIV prevention among refugees and mobile populations: situation assessment of sudanese refugees. Disasters. 2003;27(1):1–15.

Nasir EF, Marthinussen MC, Åstrøm AN. HIV/AIDS-related attitudes and oral impacts on daily performances: a cross-sectional study of sudanese adult dental patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:335.

Mahfouz AA, Alakija W, al-Khozayem AA, al-Erian RA. Knowledge and attitudes towards AIDS among primary health care physicians in the Asir Region, Saudi Arabia. J R Soc Health. 1995;115(1):23–5.

Memish ZA, Filemban SM, Bamgboyel A, Al Hakeem RF, Elrashied SM, Al-Tawfiq JA. Knowledge and attitudes of doctors toward people living with HIV/AIDS in Saudi Arabia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(1):61–7.

Arheiam A, El Tantawi M, Al-Ansari A, Ingafou M, El Howati A, Gaballah K, AbdelAziz W. Arab dentists’ refusal to treat HIV positive patients: a survey of recently graduated dentists from three Arab dental schools. Acta Odontol Scand. 2017;75(5):355–60 Epub 2017 Apr 21. Erratum in: Acta Odontol Scand 2017; 75(8): 634.

Hassan ZM, Wahsheh MA. Knowledge and attitudes of jordanian nurses towards patients with HIV/AIDS: findings from a nationwide survey. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2011;32(12):774–84.

Gańczak M, Barss P, Alfaresi F, Almazrouei S, Muraddad A, Al-Maskari F. Break the silence: HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes, and educational needs among arab university students in United Arab Emirates. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(6):572.e1-8.

Shama M, Fiala LE, Abbas MA. HIV/AIDS perceptions and risky behaviors in squatter areas in Cairo, Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2002;77(1–2):173–200.

Alwafi HA, Meer AMT, Shabkah A, Mehdawi FS, El-Haddad H, Bahabri N, Almoallim H. Knowledge and attitudes toward HIV/AIDS among the general population of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11(1):80–4.

Al Tall YR, Mukattash TL, Sheikha H, Jarab AS, Nusair MB, Abu-Farha RK. An assessment of HIV patient’s adherence to treatment and need for pharmaceutical care in Jordan. Int J Clin Pract. 2020;74(7):e13509.

Valadez JJ, Berendes S, Jeffery C, Thomson J, Ben Othman H, Danon L, Turki AA, Saffialden R, Mirzoyan L. Filling the knowledge gap: measuring HIV Prevalence and Risk factors among men who have sex with men and female sex workers in Tripoli, Libya. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e66701.

Kabbash IA, Abo Ali EA, Elgendy MM, Abdrabo MM, Salem HM, Gouda MR, Elbasiony YS, Elboshy N, Hamed M. HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination among health care workers at Tanta University Hospitals, Egypt. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018;25(31):30755–62.

Abdelrahman I, Lohiniva AL, Kandeel A, Benkirane M, Atta H, Saleh H, El Sayed N, Talaat M. Learning about barriers to care for people living with HIV in Egypt: a qualitative exploratory study. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14(2):141–7.

El-Sayyed N, Kabbash IA, El-Gueniedy M. Knowledge, attitude and practices of egyptian industrial and tourist workers towards HIV/AIDS. EMHJ. 2008;14(5):1126–35.

Bashir F, Ba Wazir M, Schumann B, Lindvall K. The realities of HIV prevention. A closer look at facilitators and challenges faced by HIV prevention programmes in Sudan and Yemen. Glob Health Action. 2019;12(1):1659098.

Elgalib A, Shah S, Al-Habsi Z, Al-Fouri M, Lau R, Al-Kindi H, Al-Rawahi B, Al-Abri S. The cascade of HIV care in Oman, 2015–2018: a population-based study from the Middle East. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;90:28–34.

Barry M, Ghonem L, Albeeshi N, Alrabiah M, Alsharidi A, Al-Omar HA. Resource utilization and caring cost of people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLHIV) in Saudi Arabia: a Tertiary Care University Hospital Experience. Healthc (Basel). 2022;10(1):118.

Bein M, Coker-Farrell EY. The association between medical spending and health status: a study of selected african countries. Malawi Med J. 2020;32(1):37–44.

Khamis J, Ghaddar A. HIV/AIDS in Syria and the response of the National AIDS Program during the war. Sex Transm Infect. 2018;94(3):173.

Marih L, Sawras V, Pavie J, Sodqi M, Malmoussi M, Tassi N, Bensghir R, Nani S, Lahsen AO, Laureillard D, El Filali KM, Champenois K, Weiss L. Missed opportunities for HIV testing in patients newly diagnosed with HIV in Morocco. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):48.

Elgalib A, Al-Sawafi H, Kamble B, Al-Harthy S, Al-Sariri Q. Multidisciplinary care model for HIV improves treatment outcome: a single-centre experience from the Middle East. AIDS Care. 2018;30(9):1114–9.

Al-Iryani B, Basaleem H, Al-Sakkaf K, Crutzen R, Kok G, van den Borne B. Evaluation of a school-based HIV prevention intervention among yemeni adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:279.

Saleh MA, Al-Ghamdi YS, Al-Yahia OA, Shaqran TM, Mosa AR. Impact of health education program on knowledge about AIDS and hiv transmission in students of secondary schools in buraidah city, saudi arabia: an exploratory study. J Family Community Med. 1999;6(1):15–21.

Al-Iryani B, Basaleem H, Al-Sakkaf K, Kok G, van den Borne B. Process evaluation of school-based peer education for HIV prevention among yemeni adolescents. SAHARA J. 2013;10(1):55–64.

Himmich H, Ouarsas L, Hajouji FZ, Lions C, Roux P, Carrieri P. Scaling up combined community-based HIV prevention interventions targeting truck drivers in Morocco: effectiveness on HIV testing and counseling. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:208.

Maatouk I, Nakib ME, Assi M, Farah P, Makso B, Nakib CE, Rady A. Community-led HIV self-testing for men who have sex with men in Lebanon: lessons learned and impact of COVID-19. Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;19(Suppl 1):50.

Lohiniva AL, Kamal W, Benkirane M, Numair T, Abdelrahman M, Saleh H, Zahran A, Talaat M, Kandeel A. HIV Stigma toward People living with HIV and Health Providers Associated with their care: qualitative interviews with Community Members in Egypt. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2016;27(2):188–98.

Aunon FM, Wagner GJ, Maher R, Khouri D, Kaplan RL, Mokhbat J. An exploratory study of HIV Risk Behaviors and Testing among male sex workers in Beirut, Lebanon. Soc Work Public Health. 2015;30(4):373–84.

Badahdah AM. Stigmatization of persons with HIV/AIDS in Saudi Arabia. J Transcult Nurs. 2010;21(4):386–92.

Khalaf I, Abu Moghli F, Froelicher ES. Youth-friendly reproductive health services in Jordan from the perspective of the youth: a descriptive qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010;24(2):321–31.

Ghazeeri G, Zebian D, Nassar AH, Harajly S, Abdallah A, Hakimian S, Skaiff B, Abbas HA, Awwad J. Knowledge, attitudes and awareness regarding fertility preservation among oncologists and clinical practitioners in Lebanon. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2016;19(2):127–33.

Arafa MA, Rabah DM. Attitudes and practices of oncologists toward fertility preservation. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(3):203–7.

Rabah DM, Wahdan IH, Merdawy A, Abourafe B, Arafa MA. Oncologists’ knowledge and practice towards sperm cryopreservation in arabic communities. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4(3):279–83.

Eldein HN. Family physicians’ attitude and practice of infertility management at primary care–Suez Canal University, Egypt. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;15:106.

Eshra DK, Dorgham LS, el-Sherbini AF. Knowledge and attitudes towards premarital counselling and examination. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 1989;64(1–2):1–15.

Melaibari M, Shilbayeh S, Kabli A. University students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards the National Premarital Screening Program of Saudi Arabia. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2017;92(1):36–43.

Abdulah Al Turki Y. Should an inquiry about sexual health, as a reflection of vascular health, be part of routine physicals for young men? Results from an outpatient study. Int J Impot Res. 2009;21(6):362–5.

Abdulmohsen MF, Abdulrahman IS, Al-Khadra AH, Bahnassy AA, Taha SA, Kamal BA, Al-Rubaish AM, Ai-Elq AH. Physicians’ knowledge, attitude and practice towards erectile dysfunction in Saudi Arabia. EMHJ. 2004;10(4–5):648–54.

Abu Ali RM, Abed MA, Khalil AA, Al-Kloub MI, Ashour AF, Alnsour IA. A survey on sexual counseling for patients with Cardiac Disease among Nurses in Jordan. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;33(5):467–73.

Bdair IA, Maribbay GL, Perceived Knowledge. Practices, Attitudes and Beliefs of jordanian nurses toward sexual Health Assessment of Patients with Coronary Artery Diseases. Sex Disabil. 2020;38:491–502.

Farrag S, Hayter M. A qualitative study of egyptian school nurses’ attitudes and experiences toward sex and relationship education. J Sch Nurs. 2014;30(1):49–56.

Salameh P, Zeenny R, Salamé J, Waked M, Barbour B, Zeidan N, Baldi I. Attitudes towards and practice of sexuality among University students in Lebanon. J Biosoc Sci. 2016;48(2):233–48.

Elmahy AG. Reaching egyptian gays using social media: a Comprehensive Health Study and a Framework for Future Research. J Homosex. 2018;65(13):1867–76.

Gausman J, Othman A, Al-Qotob R, Shaheen A, Abu Sabbah E, Aldiqs M, Hamad I, Dabobe M, Langer A. Health care professionals’ attitudes towards youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services in Jordan: a cross-sectional study of physicians, midwives and nurses. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):84.

Naal H, Abboud S, Harfoush O, Mahmoud H. Examining the Attitudes and Behaviors of Health-care Providers toward LGBT Patients in Lebanon. J Homosex. 2020;67(13):1902–19.

Inhorn MC, Shrivastav P. Globalization and reproductive tourism in the United Arab Emirates. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2010;22(3 Suppl):68S–74S.

Ghazal-Aswad S, Zaib-Un-Nisa S, Rizk DE, Badrinath P, Shaheen H, Osman N. A study on the knowledge and practice of contraception among men in the United Arab Emirates. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2002;28(4):196–200.

Hamdan-Mansour AM, Malkawi AO, Sato T, Hamaideh SH, Hanouneh SI. Men’s perceptions of and participation in family planning in Aqaba and Ma’an governorates. Jordan EMHJ. 2016;22(2):124–32.

Ismael AS, Sabir Zangana JM. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of condom use among males aged (15–49) years in Erbil Governorate. Glob J Health Sci. 2012;4(4):27–36.

Kabbash IA, Hassan NM, Al-Nawawy AN, Attalla AA, Mekheimer SI. Evaluation of HIV voluntary counselling and testing services in Egypt. Part 1: client satisfaction. EMHJ. 2010;16(5):481–90.

Barakat M, Thiab S, Thiab S, Al-Qudah RA, Akour A. Knowledge and perception regarding the development and acceptability of male contraceptives among pharmacists: a mixed sequential method. Am J Mens Health. 2022;16(1):15579883221074855.

Mustafa MA, Mumford SD. Male attitudes towards family planning in Khartoum, Sudan. J Biosoc Sci. 1984;16(4):437–49.

Nada KH, Suliman el DA. Violence, abuse, alcohol and drug use, and sexual behaviors in street children of Greater Cairo and Alexandria, Egypt. AIDS. 2010;24 Suppl 2:S39-44.

Setayesh H, Roudi-Fahimi F, Feki SE, et al. HIV in the Middle East: low prevalence but not low risk. Washington: Population Reference Bureau; 2013.

Gokengin D, Doroudi F, Tohme J, et al. HIV/AIDS: trends in the Middle East and North Africa region. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;44:66–73.

Al-Iryani B, Al-Sakkaf K, Basaleem H, Kok G, van den Borne B. Process evaluation of a three-year community-based peer education intervention for HIV prevention among yemeni young people. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2010;31(2):133–54.

Abu-Raddad LJ, Hilmi N, Mumtaz G, et al. Epidemiology of HIV infection in the Middle East and North Africa. AIDS. 2010;24:5–23.

Baroudi M, Stoor JP, Blåhed H, Edin K, Hurtig AK. Men and sexual and reproductive healthcare in the nordic countries: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e052600.

Eldib A, Tashani OA. Infertility in the middle East and North Africa Region: a systematic review with meta-analysis of prevalence surveys. Libyan J Med Sci. 2018;2:37–44.

Albakr A, Arafa M, Elbardisi H, ElSaid S, Majzoub A. Premature ejaculation: an investigative study into assumptions, facts and perceptions of patients from the Middle East (PEAP STUDY). Arab J Urol. 2021;19(3):303–9.

El-Sakka AI. Erectile dysfunction in arab countries. Part I: prevalence and correlates. Arab J Urol. 2012;10(2):97–103.

Ammar NH. Beyond the shadows: domestic spousal violence in a “democratizing”. Egypt Trauma Violence & Abuse. 2006;7(4):244–59.

Yount KM, Li L. Women’s “justification” of domestic violence in Egypt. J Marriage Fam. 2009;71(5):1125–40.

Elghossain T, Bott S, Akik C, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence against women in the arab world: a systematic review. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2019;19:29.

Safdar B, Naveed S, Chaudhary AMD, Saboor S, Zeshan M, Khosa F. Gender disparity in grants and awards at the National Institute of Health. Cureus. 2021;13(4):e14644.

Abouelenin M. Gender. Resources, and intimate Partner Violence Against Women in Egypt before and after the Arab Spring. Violence Against Women. 2022;28(2):347–74.

Asmare G, Nigatu D, Debela Y. Factors affecting men’s involvement in maternity waiting home utilization in North Achefer district, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(2):e0263809.

Kotelchuck M, Levy RA, Nadel HM. Voices of fathers during pregnancy: the MGH prenatal care obstetrics Fatherhood Study Methods and results. Matern Child Health J 2022 Jun 29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-022-03453-y. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35768674.

Guspianto IIN, Asyary A. Associated Factors of Male Participation in Antenatal Care in Muaro Jambi District, Indonesia. J Pregnancy. 2022;2022:6842278.

Nyamai PK, Matheri J, Ngure K. Prevalence and correlates of male partner involvement in antenatal care services in eastern Kenya: a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2022;41:167.

Boniphace M, Matovelo D, Laisser R, Yohani V, Swai H, Subi L, Masatu Z, Tinka S, Mercader HFG, Brenner JL, Mitchell JL. The fear of social stigma experienced by men: a barrier to male involvement in antenatal care in Misungwi District, rural Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):44.

Bawadi HA, Qandil AM, Al-Hamdan ZM, Mahallawi HH. The role of fathers during pregnancy: a qualitative exploration of arabic fathers’ beliefs. Midwifery. 2016;32:75–80.

Lucente A. Three countries where abortion is legal in the Middle East and North Africa. 2022. Available at https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/05/three-countries-where-abortion-legal-middle-east-and-north-africa.

Hessini L. Abortion and Islam: policies and practice in the Middle East and North Africa. Reprod Health Matters. 2007;15/29:75–84.

Musallam B. Sex and society in Islam: birth control before the nineteenth century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1989.

Bowen DL. Abortion, Islam, and the 1994 Cairo population conference. Int J Middle East Stud. 1997;29/2:161–84.

Asman O. Abortion in islamic countries: legal and religious aspects. Med Law. 2004;23/1:73–89.

Shapiro GK. Abortion law in muslim-majority countries: an overview of the islamic discourse with policy implications. Health Policy and Plan. 2014;29/4:483–94.

Hajri S, Raifman S, Gerdts C, et al. This is real misery: experiences of women denied legal abortion in Tunisia. PLoS ONE. 2015;10/12:e0145338.

Maffi I, Affes M. La santé sexuelle et reproductive en tunisie: institutions médicales, lois et itinéraires thérapeutiques des femmes après la revolution. L’Année du Maghreb. 2017;17/2:151–68.

Gruenais M. La publicisation du débat sur l’avortement au Maroc: L’Etat marocain en action. L’Année du Maghreb. 2017;17/2:219–34.

Maffi I. Abortion in Tunisia after the revolution: bringing a new morality into the old reproductive order. Glob Public Health. 2018;13/6:680–91.

Shahawy S, Diamond MB. Perspectives on induced abortion among palestinian women: Religion, culture and access in the occupied palestinian territories. Cult Health Sex. 2018;20/3:289–305.

UNHCR. Middle East and North Africa. 2021a. Available at https://reporting.unhcr.org/mena.

Logie CH, et al. Exploring associations between adolescent sexual and reproductive health stigma and HIV testing awareness and uptake among urban refugee and displaced youth in Kampala. Uganda SRHM. 2019;27(3):86–106.

Kaczkowski W, Swartout KM. Exploring gender differences in sexual and reproductive health literacy among young people from refugee backgrounds. Cult Health Sex. 2020;22(4):369–84.

UNHCR. Middle East and North Africa. 2021b. Available at https://reporting.unhcr.org/globalreport2021/mena.

Stycos JM, Sayed HA, Avery R. An evaluation of the population and development program in Egypt. Demography. 1985;22(3):431–43.

Sallam SA, Mahfouz AA, Alakija W, al-Erian RA. Continuing medical education needs regarding AIDS among egyptian physicians in Alexandria, Egypt and in the Asir Region, Saudi Arabia. AIDS Care. 1995;7(1):49–54.

Warren CW, Hiyari F, Wingo PA, Abdel-Aziz AM, Morris L. Fertility and family planning in Jordan: results from the 1985 Jordan husbands’ fertility survey. Stud Fam Plann. 1990;21(1):33–9.

Fido A, Al Kazemi R. Survey of HIV/AIDS knowledge and attitudes of Kuwaiti family physicians. Fam Pract. 2002;19(6):682–4.

El-Sony AI. The cost to health services of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) co-infection among tuberculosis patients in Sudan. Health Policy. 2006;75(3):272–9.

Kobeissi L, Inhorn MC, Hannoun AB, Hammoud N, Awwad J, Abu-Musa AA. Civil war and male infertility in Lebanon. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(2):340–5.

Kahhaleh JG, El Nakib M, Jurjus AR. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices in Lebanon concerning HIV/AIDS, 1996–2004. EMHJ. 2009;15(4):920–33.

Al-Serouri AW, Anaam M, Al-Iryani B, Al Deram A, Ramaroson S. AIDS awareness and attitudes among yemeni young people living in high-risk areas. EMHJ. 2010;16(3):242–50.

Kabbash IA, Mekheimer Sl, Hassan NM, Al-Nawawy AN, Attalla AA. Evaluation of HIV voluntary counselling and testing services in Egypt. Part 2: service providers’ satisfaction. EMHJ. 2010;16(5):491–7.

Ellepola AN, Joseph BK, Sundaram DB, Sharma PN. Knowledge and attitudes towards HIV/AIDS amongst Kuwait University dental students. Eur J Dent Educ. 2011;15(3):165–71.

Saleh WF, Gamaleldin SF, Abdelmoty HI, Raslan AN, Fouda UM, Mohesen MN, Youssef MA. Reproductive health and HIV awareness among newly married egyptian couples without formal education. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;126(3):209–12.

Othman SM. Knowledge about HIV/AIDS among high school students in Erbil city/Iraq. Glob J Health Sci. 2014;7(1):16–23.

Akhu-Zaheya LM, Masadeh AB. Sexual information needs of arab-muslim patients with cardiac problems. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;14(6):478–85.

AlMuzaini AA, Yahya AS, Ellepola AN, Sharma PN. HIV/AIDS: dental assistants’ self-reported knowledge and attitudes in Kuwait. Int Dent J. 2015;65(2):96–102.

Haroun D, El Saleh O, Wood L, Mechli R, Al Marzouqi N, Anouti S. Assessing knowledge of, and Attitudes to, HIV/AIDS among University students in the United Arab Emirates. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0149920.

Lohiniva AL, Benkirane M, Numair T, Mahdy A, Saleh H, Zahran A, Okasha O, Talaat M, Kamal W. HIV stigma intervention in a low-HIV prevalence setting: a pilot study in an egyptian healthcare facility. AIDS Care. 2016;28(5):644–52.

Sexty RE, Hamadneh J, Rösner S, Strowitzki T, Ditzen B, Toth B, Wischmann T. Cross-cultural comparison of fertility specific quality of life in german, hungarian and jordanian couples attending a fertility center. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:27.

Ashry M, Ziady H, Hameed M, Mohammed F. Health-related quality of life in healthy children and adolescents of HIV-infected parents in Alexandria, Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2017;92(4):212–9.

Spindler E, Bitar N, Solo J, Menstell E, Shattuck D. Jordan’s 2002 to 2012 fertility stall and parallel USAID Investments in Family Planning: Lessons from an Assessment to Guide Future Programming. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2017;5(4):617–29.

Zaidouni A, Ouasmani F, Benbella A, Ktiri F, Abidli Z, Bezad R. What are the needs of infertile moroccan couples in assisted Reproductive Technology?: exploratory qualitative study in the first fertility public center in Morocco. Bangladesh J Medical Sci. 2020;19(4):697–704.

Shah S, Elgalib A, Al-Wahaibi A, Al-Fori M, Raju P, Al-Skaiti M, Al-Mashani HN, Duthade K, Omaar I, Muqeetullah M, Mitra N, Shah P, Amin M, Morkos E, Vaidya V, Al-Habsi Z, Al-Abaidani I, Al-Abri SS. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices related to HIV Stigma and discrimination among Healthcare Workers in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2020;20(1):e29–36.

Sait M, Aljarbou A, Almannie R, Binsaleh S. Knowledge, attitudes, and perception patterns of contraception methods: cross-sectional study among saudi males. Urol Ann. 2021;13(3):243–53.

Karim SI, Irfan F, Saad H, Alqhtani M, Alsharhan A, Alzhrani A, Alhawas F, Alatawi S, Alassiri M, Ahmed MA. A. Men’s knowledge, attitude, and barriers towards emergency contraception: a facility based cross-sectional study at King Saud University Medical City. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(4):e0249292.

Kapoor NR, Langer A, Othman A, Gausman J. Healthcare practitioners experiences in delivering sexual and reproductive health services to unmarried adolescent clients in Jordan: results from a cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):31.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was available for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WEA conceived the study and all authors contributed to refining the study concept and methods. WEA, MA and AM obtained data and HE, MM and AA prepared and analysed data with substantial methodological input from WEA, MA, AM, KA and AAA. WEA and MA accessed and verified the data. All authors participated in the interpretation of data. WEA wrote the first draft, and all authors critically edited it. All authors read and approved the final submitted manuscript and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board in Hamad Medical Corporation doesn’t need an approval or consent for review articles.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

El Ansari, W., Arafa, M., Elbardisi, H. et al. Scoping review of sexual and reproductive healthcare for men in the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region: a handful of paradoxes?. BMC Public Health 23, 564 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14716-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14716-2