Abstract

Background

Obesity and unemployment are complex social and health issues with underlying causes that are interconnected. While a clear link has been established, there is lack of evidence on the underlying causal pathways and how health-related interventions could reduce obesity and unemployment using a holistic approach.

Objectives

The aim of this realist synthesis was to identify the common strategies used by health-related interventions to reduce obesity, overweight and unemployment and to determine for whom and under what circumstances these interventions were successful or unsuccessful and why.

Methods

A realist synthesis approach was used. Systematic literature searches were conducted in Cochrane library, Medline, SocIndex, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Scopus, and PsychInfo. The evidence from included studies were synthesised into Context-Mechanism-Outcome configurations (CMOcs) to better understand when and how programmes work, for which participants and to refine the final programme theory.

Results

A total of 83 articles met the inclusion criteria. 8 CMOcs elucidating the contexts of the health-related interventions, underlying mechanisms and outcomes were identified. Interventions that were tailored to the target population using multiple strategies, addressing different aspects of individual and external environments led to positive outcomes for reemployment and reduction of obesity.

Conclusion

This realist synthesis presents a broad array of contexts, mechanisms underlying the success of health-related interventions to reduce obesity and unemployment. It provides novel insights and key factors that influence the success of such interventions and highlights a need for participatory and holistic approaches to maximise the effectiveness of programmes designed to reduce obesity and unemployment.

Trial registration

PROSPERO 2020 CRD42020219897.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Obesity and unemployment are critically intertwined social and health issues which adversely impact life expectancy, quality of life, mental health and lead to increased mortality and morbidity [1,2,3,4]. Whether obesity leads to unemployment or is a consequence of unemployment is not fully determined, however there is strong evidence showing that both conditions are reciprocal and can be the cause or consequence of each other [5, 6]. The recent coronavirus pandemic and cost of living crisis have exacerbated the challenges of being unemployed and living with low income [7, 8]. Furthermore, they have highlighted the risks of living with overweight and obesity and the need for interventions to address the underlying social and economic determinants [9, 10].

Several studies have shown a consistent link between obesity and unemployment [11,12,13] and single transitions into unemployment and persistent unemployment have been associated with poor mental health, general health and obesity [12]. In a cohort study of 87,796 participants, obesity was associated with a higher risk of unemployment and sickness absence compared with individuals with normal weight [5]. Additionally, evidence suggests that long-term obesity and developing obesity in mid-adulthood increases the risk of poor work ability [14]. Taken together, this evidence suggests that reemployment might be an important strategy to improve the health of unemployed individuals living with overweight or obesity.

Evidence on the link between obesity, income inequality and unemployment also highlight the underlying effects of obesity determinants related to dietary and physical activity behaviours. Individuals from lower socioeconomic groups are more likely to exhibit a greater risk of higher consumption of energy dense foods, lower density of micronutrients in their diet, lower consumption of fruits and vegetables and lower levels of physical activity [15,16,17]. Unemployment has an immediate effect on food expenditure and longitudinal data showed that this decreased with the duration of unemployment and is also associated with the purchase of cheaper, energy dense foods but lower purchase of fruits and vegetables [6, 18]. A review on neighbourhood disparities in access to fast-food outlets and convenience shops showed that, low-income neighbourhoods offered greater access to food sources that promote unhealthy eating thereby worsening the problem [19]. Compared to the general population, unemployed persons are more sedentary and show lower levels of physical activity [20, 21].

The underlying causes of obesity and unemployment are similar and often very complex. Similar to the challenge of maintaining a healthy weight, finding employment or reemployment after job loss is a complex and difficult task that requires extensive motivation and self-regulation [22, 23]. Secondly obesity and job loss impact on certain characteristics, like self-esteem and self-efficacy and this negatively influences access to employment and reduces performance in the labour market [4, 24]. Individuals living with obesity or in long-term unemployment may also be discriminated against due to prejudice and stereotyping by employers [25,26,27], further decreasing their chances of obtaining employment and earning an income to enable the maintenance of a healthy lifestyle. Unemployment, low income and obesity are also associated with higher levels of psychosocial stressors for example, decreased control over life, higher insecurity, social isolation, stress and mental disorders [28]. This may lead to maladaptive coping strategies, such as eating energy-dense foods to alleviate negative emotions and stress resulting in a vicious cycle of overweight and unemployment [29]. This requires a range of interventions to address the complex interplay between socioeconomic factors, disadvantage, health and wellbeing. These include interventions that address skills, availability and access to healthy food options, availability and access to physical activity resources, neighbourhood safety, stress, discrimination, and dysfunctional social networks. Holistic multicomponent responses across these domains have the potential to be benefit both obese and unemployed individuals.

Currently, research gaps exist on the mechanisms and pathways that underscore the complex relationship between food insecurity, unemployment, low income, diet, and weight outcomes. There is also a lack of synthesised evidence on how health-related interventions could reduce obesity and increase employment. While some systematic reviews [30, 31] have suggested a beneficial effect of interventions in reducing obesity and increasing employment, the evidence has been inconclusive. It is also not clear which contexts or mechanisms are required for the successful implementation and effective uptake of such interventions. There is, therefore, the need to synthesise the evidence on interventions that have been shown to reduce obesity and increase employment to examine why and how these interventions worked and for whom.

Research questions

-

1.

What health-related interventions have been used to reduce overweight, obesity and unemployment in adults?

-

2.

What are the common approaches used in interventions designed to reduce overweight, obesity and unemployment in adults?

-

3.

What are the contexts and mechanisms that have contributed to the success or failure of these interventions?

Study objectives

The objectives of this realist systematic review were to synthesise the current evidence on health-related interventions designed to reduce obesity and unemployment. Additionally, this study explored the contexts and mechanisms which underly the effectiveness of such interventions and summarised the common strategies that have been used to address obesity and unemployment.

Methods

This realist synthesis was conducted using steps outlined in the Ray Pawson’s realist review method [32] and according to the Realist And MEta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) quality standards for realist synthesis [33] and a registered protocol published in the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42020219897). Reporting was carried out using the RAMESES publication standards [34] (Supplementary Table S1) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [35] (Supplementary Table S2).

Rationale for using realist synthesis

In order to achieve the objectives of the present review, a realist synthesis approach was chosen. Simply knowing that interventions designed to reduce obesity or unemployment work is not enough for policymakers to decide on the types of interventions to be implemented under different contexts. It is, therefore, very important to examine these interventions closely to determine which aspects led to success or failure in different circumstances and for which participants. While the majority of investigations so far may deem an intervention to work, without considering the background contexts or mechanisms in determining outcomes, such programmes may show differential results when implemented in different contexts during scaling-up. Additionally, while several systematic reviews [30, 36,37,38,39] have attempted to summarise evidence on interventions designed to reduce obesity and unemployment, the results have been inconclusive with several recommending further studies to clarify mechanisms and outcomes. This is because of unsystematic reporting within published intervention studies and the pooling of average intervention effect sizes within systematic literature reviews of studies with significant between-study heterogeneity. This results in a failure to identify effective intervention components that are specific enough and pragmatically relevant for the intervention to be scaled up where necessary [40].

In contrast, realist synthesis uses the Context-Mechanism-Outcome (CMO) heuristic in which context is the backdrop or background environment of intervention programmes [32, 41]. Mechanisms are defined as the resources generated from programme strategies and how people respond to resources offered through those strategies [32, 42]. As such, the realist approach is highly suited to clarifying what intervention approaches work, for whom, under what circumstances, and how [32]. Realist synthesis additionally lends itself to the review of complex interventions such as those designed to reduce obesity and unemployment because it accounts for context, mechanisms underlying such interventions as well as outcomes in the process of systematically and transparently synthesising relevant literature [43].

Development of the initial programme theory

Scoping of existing literature was conducted to develop the initial programme theory (IPT) and to guide the synthesis. This involved a combination of discussions with team members with expert knowledge in the subject area, exploratory search and brief review of key articles identified at the beginning stage of the review. Initial drafts of the IPT and research questions were further discussed with project partners to further refine the aim of the proposed review according to the priorities of the partner organisations.

Study search, screening and study selection

Screening of eligible studies, full-text assessment, data extraction, and quality appraisal of studies was independently carried out by two authors (SDA, DW). Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus and, where necessary, moderated by a third reviewer from the team. Systematic searches were conducted in 6 databases including the Cochrane library, Medline, SocIndex, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Scopus, and PsychInfo without any language restrictions in July 2020. These databases were included because they had been identified in the preliminary search as containing the journals relevant to the research topic. The literature search was carried out with assistance of an experienced librarian. The search was iterative and continued throughout the review. Medical subject headings and key word searches were conducted in Medline, CINAHL, SocIndex, PsychINFO and Cochrane library, whereas searches in Scopus were carried out using only key word searches. The full search strategy for all the searches combined terms related to obesity or overweight or synonyms (e.g., weight gain, weight loss, body mass index weight, body weight maintenance), unemployment or jobseeker of synonyms (e.g., unemployed, job loss, jobless) and intervention strategies (e.g., weight reduction programme, lifestyle intervention, health promotion, healthy diet, physical activity). The full searches for all the databases are provided in Supplementary Table S3. Medical subject headings and key word searches were conducted in Medline, CINAHL, SocIndex, PsychINFO and Cochrane library, whereas searches in Scopus were carried out using only key word searches.

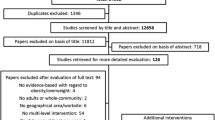

Initial screening of titles and abstracts of the retrieved searches were conducted separately for each database and articles identified to be relevant were exported into Endnote Web for removal of duplicates. After removal of duplicates, further screening of abstracts was carried out to identify articles which were potentially relevant for inclusion in the review. Full-text articles were independently reviewed by two authors for inclusion using predefined eligibility criteria which included questions to assess a study’s relevance for inclusion in the review. Studies that described health-related or behavioural interventions (educational, skills training, health promotion, psychological, behavioural therapy, counselling) focused on promoting healthy lifestyle, wellbeing and employment in individuals were included. Full-text articles that met the inclusion criteria were added to a database for subsequent data extraction.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Studies conducted in adults 18 years and above living with overweight or obesity.

-

Studies conducted in adults 18 years and above who are unemployed or jobseekers.

Exclusion criteria

-

Studies involving children and adolescents below 18 years.

-

Studies specifically conducted in older adults (65 years and above).

-

Interventions conducted in individuals with specific health conditions.

-

In-vitro or non-human studies.

-

Interventions involving drugs or surgery e.g., bariatric surgery, interventions targeted at changing the food environment or fiscal and regulatory policies.

Data extraction

Data extraction was carried out independently by two members of the team. The first stage included extracting data on study characteristics including first author, country, target group, study design, sample size, description of intervention, duration, programme theory, evaluation methods, and study outcomes. The second stage involved extracting data on contexts, mechanisms, information on the effectiveness of the interventions and facilitators and barriers for the implementation of the interventions which contributed to the refinement of the final programme theory.

Quality appraisal

Consistent with realist synthesis methodology, quality appraisal of included studies was conducted to assess their relevance and rigour. Methodological rigour refers to whether the methods used to generate the relevant data were credible, plausible and trustworthy and relevance refers to relevance of the contributions of any section of the study to refining the underlying theory and context-mechanism-outcome evidence [32, 44]. Relevance in this synthesis was assessed by considering whether the paper had a direct relevance to our review by contributing to the final program theory. Assessment for rigour was based on the extent to which studies provided a detailed description of methods and the level of generalisability [45] of findings. Two reviewers initially appraised two articles together and discussed the results as a team to ensure a consistent approach for this process.

Data synthesis and analysis

Data synthesis and analysis was conducted using in-depth realist synthesis [32] and a realist approach to thematic analysis [46]. This involved identification of how different strategies, mechanisms and contexts interact to produce particular outcomes resulting in the final programme theory. It included capturing data from qualitative discussions found in the included studies, describing how and why an intervention or parts of an intervention may or may not work and in what circumstances. Data on aspects of the study’s history and context, especially those highlighted as important by the study’s authors and any theories or mechanisms postulated (or assumed) by the study’s authors to explain the success or failure of the intervention, were also extracted. This information was tabulated in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and organised into CMOcs for each included study. From this, common overarching themes across the studies that contributed to the refined programme theory were identified. The articles were further re-read, and iteratively revised to capture additional themes or concepts that might contribute to the refined programme theory. Finally, an overall synthesis of these combinations of contexts, mechanisms and outcomes, independent of individual study details was conducted to generate the refined programme theory.

Results

A total of 83 studies meeting the inclusion criteria and assessment for rigor and relevance were included. Study screening, eligibility, and selection processes are shown in Fig. 1.

Initial programme theory

Figure 2 illustrates the initial programme theory in terms of CMOc propositions based on brief initial review of the relevant literature, discussions and understanding drawn from professional experience. This process identified both individual and environmental factors to underlie the context of the interventions and how these interact with mechanisms to result in outcomes. This theory building was focused on key assumptions on how interventions designed to reduce overweight, obesity and unemployment work. Using our synthesis, we then set out to refine this initial program theory.

Characteristics of included studies

Tables 1 and 2 present the summary and main findings of the studies included in this review. A total of 83 studies were included in this review and of these, 66.2% targeted overweight or obese participants and 33.7% unemployed individuals, jobseekers or trainees. 54.2% of included studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), 17 (20.5%) intervention studies, 19 (22.9%) quasi experimental studies, 1(1.2%) qualitative study and 1(1.2%) controlled study. The studies included were conducted in 24 countries with the majority (23.3%) in the USA, 14.0% in the United Kingdom, 12.8% in Australia and 49.9% in other countries including Germany, Finland, The Netherlands, Spain, Israel and Malaysia. Most studies (67.4%, n = 56) involved both male and female participants with age ranging from 18 to 64 years. Evaluation methods included both objective and subjective methods (45.8%), subjective methods only (44.6%) and objective methods only (8.4%). Reported outcomes included weight, BMI and other anthropometric measures [23, 53, 71, 73,74,75, 77, 79, 80, 82, 84, 85, 87, 89, 91,92,93,94,95, 98, 100, 101, 103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112, 114, 115, 117,118,119,120, 124], reemployment [22, 47, 52, 54, 57, 59, 61, 62, 65, 67,68,69], healthy eating knowledge and healthy eating behaviour [49, 56, 72, 74, 76, 78, 87, 98, 100, 110, 111, 113, 118,119,120, 124], self-efficacy and self-esteem [27, 48,49,50,51, 54, 56, 57, 59, 61, 66,67,68,69,70, 72, 75, 76, 78, 82, 86, 88, 90, 92, 96, 101, 102, 108, 112, 113, 118, 120, 121, 124], physical activity [20, 23, 74, 82,83,84, 89,90,91, 93, 96, 98, 104, 106, 107, 110, 111, 121, 124], job search and entrepreneurial skills [22, 55, 56] and wellbeing, mental and physical health [58, 59, 74, 83, 87, 97, 101, 121, 124].

Common approaches used in interventions designed to reduce overweight, obesity and unemployment in adults

Intervention strategies that were commonly used by studies to address obesity and unemployment were identified and categorised as follows: (i) building knowledge and skills to enable behaviour change [20, 22, 23, 49, 53, 55, 56, 60, 63, 64, 68, 69, 71, 72, 74, 75, 77,78,79,80,81, 83,84,85,86,87, 89, 92, 93, 96, 98, 99, 101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116, 118,119,120, 122, 124, 125], (ii) increasing motivation [48, 58, 67, 72, 74, 88, 89, 99, 113, 117, 119, 124] (iii) cognitive behaviour therapy/positive psychology [27, 61, 65, 75, 76], (iv) improving self-efficacy, confidence and self-esteem [47, 50, 51, 59, 62, 66, 67, 75, 79, 85, 88, 89] (v) building resilience and emotional competency [51, 54, 57, 59, 62, 66,67,68, 121], hands-on practice of behaviour [20, 52, 53, 68, 71, 77,78,79,80,81, 83,84,85, 87, 90,91,92, 95, 100, 101, 103, 105, 106, 108, 110,111,112,113, 116, 119, 121, 125] and (vii) building knowledge and skills on goal-setting, identifying barriers to achieving goals, and self-monitoring [74, 77,78,79, 82, 91, 93, 94, 96, 100, 102, 107, 108, 113, 118, 125]. The majority of studies used more than one strategy in the delivery of interventions.

Factors underlying the success or failure of interventions

Factors that contributed to the success of interventions included: longer length of intervention [71], more contact time with participants [65, 110, 114, 119], culturally or gender tailored intervention [52, 72, 75, 83, 93, 94, 99, 102, 107,108,109, 113, 114, 119, 124], regular monitoring and support [20, 51, 54, 55, 62, 75, 88, 89, 93, 97, 103, 104, 106], positive attitude of coaches [74], simplicity of tasks/messages [66, 82, 84, 85, 94, 108, 115, 119, 120], high satisfaction and acceptance of intervention [22, 58, 68, 106, 117, 121], variation in activities [56, 88], interactive and engaging activities [58, 86, 89, 94, 96, 101, 113], small changes approach [96, 107] and high compliance [95, 104, 105, 113, 115]. Factors that reduced the effectiveness of interventions included poor adherence/low compliance [90, 99, 122], lack of specificity and clarity in intervention goals [96, 124], low participation rate [64, 98, 125], short duration of intervention [71, 100], minimal contact, lack of structure and follow-up [56, 63, 97, 116] and intervention not tailored to the individual [64, 81]. Participant characteristics that influenced the success or failure of the interventions included age [49, 58, 63, 68, 78, 89, 99, 124], gender [58, 63, 64, 68], length of unemployment [58], income level, educational level, baseline BMI, self-efficacy and self-esteem [50, 51, 78, 79, 96, 124], motivation [95] and availability of social support [52].

Refined Programme theory

A total of 8 CMOCs were generated building up on the initial programme theory. These are as follows (the letter, C-context, M-mechanism and O-outcomes). The CMOcs provide a higher level of abstraction that sets out the underpinning logic behind the family of interventions strategies identified to address unemployment and obesity.

-

1.

CMO1: When participants with limited knowledge about healthy eating (C) are provided with the requisite knowledge and skills, and able to apply these new knowledge and skills (M), their healthy eating behaviour is improved (O).

-

2.

CMO2: When participants with low educational status (C) are provided with an intervention delivered in their native language, there is higher acceptance, and they are able to utilise the new skills to successfully execute new behaviour (M) and will improve healthy eating behaviour (O).

-

3.

CMO3: When participants are provided with healthy eating and physical activities tailored to their needs (C), they are able to incorporate skills and strategies into daily routine, successfully execute new skills (M) and reduce their weight and BMI (O).

-

4.

CMO4: When participants with low income (C) are provided with financial incentives and resources, they are able to purchase healthier food options (M) and will improve their healthy eating behaviour (O).

-

5.

CMO5: When participants receive healthy eating and physical activity interventions in group settings (C), they are able to obtain social support from peers (M) and will increase their physical activity levels and improve healthy eating behaviours (O).

-

6.

CMO6: When participants with limited knowledge and job search skills (C) are provided with job search skills training, they are able to apply these skills in their job search (M) and will obtain employment (O).

-

7.

CMO7: When labour market conditions are favourable (C) and participants are provided with job search and entrepreneurial skills training, participants are able to develop and apply their new employability skills (M) and will obtain employment (O).

-

8.

CMO8: When participants with low motivation and self-esteem (C) are offered self-led interventions, they will be able to develop self-regulatory skills, maintain perceptions of control over situation (M) and improve their self-efficacy and self-esteem (O).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this review represents the first use of realist synthesis to understand the determinants of the effectiveness of complex health-related interventions to reduce overweight, obesity and unemployment. Building on our initial programme theory and exploring the interactions between the contexts of the interventions, mechanisms, intervention strategies and outcomes, a number of key insights were obtained. The most common intervention strategy used by the majority of studies was knowledge and skills building through provision of workshops, lectures, information leaflets or skills training. This approach was often based on assumptions that participants lacked the requisite knowledge or skills to be able to implement healthy eating behaviour or obtain jobs. While this strategy resulted in mixed successes, more positive outcomes were observed when participants had low educational status, lower income, or when the intervention implemented tailored and culturally appropriate activities (CMO1, CMO2, CMO6). This approach enabled the acquisition of skills relevant to participants’ needs thereby facilitating the incorporation of these new skills into daily routine and increased the ability to successfully execute and maintain the new behaviour.

Evidence from research show that there is no universal model of an intervention that results in positive outcomes for all participants [126]. For example, individuals who are unemployed may have varied level of skills and overweight or obese may have different underlying determinants, therefore interventions need to be tailored to individual needs [55, 119, 126, 127]. Our synthesis indicated that age, gender, baseline educational level, BMI, self-efficacy, self-esteem and motivation impacted the success or failure of the intervention [49, 67, 71, 85, 102, 112]. Tailored activities led to higher acceptance, compliance, participation rate and satisfaction [22, 95, 104, 106]. Additionally, resources are wasted and opportunities to provide genuine help are lost if an intervention is not appropriate to the needs of an individual or the targeted group [127].

However, there is limited evidence about the cost-effectiveness of tailored interventions compared to generalised interventions. In addition, there is insufficient evidence on the most effective approaches to tailoring, including how determinants should be identified, how decisions should be made on which determinants are most important to address, and how interventions should be selected to account for the important determinants. This highlights a need for programmes co-produced with participants using participatory approaches to prioritise the needs of the target group thereby making them more meaningful and engaging.

Another key context that impacted the effectiveness of interventions was delivery of activities in group-based or individualised or self-led contexts (CMO5). Group programmes offer a more cost-effective option to individual programmes [101] and can serve as an important source of vicarious learning and social support [89]. The effectiveness may however be dependent on the demography of participants (age group, gender, culture) or sensitivity of intervention elements. In a previous study involving African American men, participants enjoyed the camaraderie and support they received from their small group and benefitted from seeing that others were struggling with and overcoming similar barriers to physical activity they faced [89]. The men in this study reported that they learned from and supported one another with strategies to overcome barriers to physical activity. On the contrary, anxiety and discomfort in group settings as well as reticence to engage in activities appeared to be a frequent issue for group-based interventions [65] and group dynamics could significantly influence uptake of activities [91]. It is therefore critical that programmes consider what works for the target population.

Other factors that accounted for success of interventions implemented to reduce weight and unemployment included, multicomponent programme activities, favourable labour market conditions (CMO7), demographic characteristics of target population and provision of financial incentives or other resources that enabled hands-on practice of behaviour (CMO4). Evidence from the literature show that interventions which had varied, diverse and engaging activities had a higher uptake and compliance leading to positive outcomes [101, 126]. For example, it is essential to combine measures for changes in nutrition, physical activity, and behaviour in interventions seeking to reduce overweight and obesity [128]. Furthermore, programmes that focus on a healthy lifestyle by concurrently offering dietary advice with behavioural strategies such as increasing physical activity are more effective than programs that focus on dietary restriction alone [83, 129], suggesting a holistic lifestyle approach is warranted. Similarly, being unemployed denies people from the manifest (income) and latent (e.g., time structure, status, and identity) benefits of having a job, therefore, to optimise the effectiveness of interventions supporting the unemployed, a combination of job search skills training, enhancing coping skills and motivational approaches are required [54, 55]. Successful re-employment has been shown to depend on favourable conditions in the labour market, demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, educational attainment), and occupational characteristics (e.g., an academic degree). Young age and high level of education are positively related to reemployment [64]; therefore, programmes need to take these contexts into account during intervention design and implementation. Finally, a key finding from this review relates to the similarities in targeting common underlying factors such as low self-efficacy and self-esteem, low socioeconomic status, low skills and psychosocial stressors for both employment and heathy weight interventions. Implementing interventions that addressed these common underlying factors as well as psychological mechanisms assumed to regulate weight and unemployment, resulted in positive weight and employment outcomes. While addressing these underlying factors may contribute to improving employability and maintaining a healthy weight, further research is warranted to elucidate the extent to which these factors are moderated by the different interventions. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that unemployment and obesity are very complex conditions, with equally complex interacting mechanisms and contexts, therefore the CMOCs identified also indicate a degree of interconnectedness and the likely potential of interactions in other to achieve successful and effective interventions.

Strengths and limitations

Our use of the realist approach of configuring contexts and mechanisms together is a key strength and adds explanatory power to help us understand how these elements interact to produce outcomes of interest in health-related interventions to reduce obesity and unemployment. Importantly, obesity and unemployment are very complex issues, and the use of realist review methodology enabled us to identify the complexity within the interventions as well as the multiple interactions between the numerous components of the implemented programmes.

The strength of the findings in this synthesis are also dependent on the comprehensiveness of the information provided on intervention contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. The majority of studies on health-rated interventions and therefore included in this synthesis were RCTs, which present a major limitation for this review. Characteristic of RCTs, there is attribution of success of interventions to randomisation and the actual programme without elucidation of why intervention was successful or the mechanisms underlying participants’ response to an intervention. There was also a lack of subgroup analyses in the majority of the studies, thus outcomes which may in fact be explained by differences among individuals were attributed to the intervention and this limited the identification of who the interventions worked for. Finally, the CMOcs identified in this review not exhaustive but rather an insight into what may be contributing to positive or negative outcomes and how certain determinants can be incorporated to achieve the desired outcomes therefore further exploration of the possible causal pathways are warranted.

Conclusions

This review was able to identify contextual mechanisms that determined observed outcomes and how those involved in health-related interventions to reduce obesity and unemployment tended to respond to the intervention. It also uncovered a number of overlooked perspectives which should be included in future research. Multicomponent interventions combining different strategies, tailored to participants, using a mix of knowledge and skill building, motivational approaches and hands-on practice resulted in positive outcomes. Participant characteristics that influenced the outcomes included age, gender, educational status, income level and these should be considered when tailoring interventions. Taken together, this review contributes to an emerging field in systematic review, in which qualitative approaches compliment and extend the findings of quantitative reviews and highlights a co-produced rather than prescriptive approach to the design and implementation of health-related interventions to reduce overweight, obesity and unemployment.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable – Realist systematic review of published studies.

Abbreviations

- CMO:

-

Context-Mechanism-Outcome

- RCT:

-

randomised controlled trial

References

Murray CJL, Aravkin AY, Zheng P, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi-Kangevari M, et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1223–49.

Savinainen M, Seitsamo J, Joensuu M. The association between changes in functional capacity and work ability among unemployed individuals. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2020;93(4):503–11.

Nurmela K, Mattila A, Heikkinen V, Uitti J, Ylinen A, Virtanen P. Identification of depression and screening for work disabilities among long-term unemployed people. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(5).

Kinge JM. Waist circumference, body mass index, and employment outcomes. Eur J Health Econ. 2017;18(6):787–99.

Bramming M, Jorgensen MB, Christensen AI, Lau CJ, Egan KK, Tolstrup JS. BMI and labor market participation: a cohort study of transitions between work, unemployment, and sickness absence. Obesity. 2019;27(10):1703–10.

Smed S, Tetens I, Boker Lund T, Holm L, Ljungdalh NA. The consequences of unemployment on diet composition and purchase behaviour: a longitudinal study from Denmark. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(3):580–92.

Nagata JM, Seligman HK, Weiser SD. Perspective: the convergence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and food insecurity in the United States. Adv Nutr. 2021;12(2):287–90.

Goudie S, Hughes I. The broken plate 2022: technical. Report. 2022; Available at: https://foodfoundation.org.uk/publication/broken-plate-2022.

O'Hearn M, Liu J, Cudhea F, Micha R, Mozaffarian D. Coronavirus disease 2019 hospitalizations attributable to cardiometabolic conditions in the United States: a comparative risk assessment analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(5):e019259.

Popkin BM, Du S, Green WD, Beck MA, Algaith T, Herbst CH, et al. Individuals with obesity and COVID-19: a global perspective on the epidemiology and biological relationships. Obes Rev. 2020;21(11):1–17.

Salmasi L, Celidoni M. Investigating the poverty-obesity paradox in Europe. Econ Hum Biol. 2017;26:70–85.

Herber GC, Ruijsbroek A, Koopmanschap M, Proper K, van der Lucht F, Boshuizen H, et al. Single transitions and persistence of unemployment are associated with poor health outcomes. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):740.

Feigl AB, Goryakin Y, Devaux M, Lerouge A, Vuik S, Cecchini M. The short-term effect of BMI, alcohol use, and related chronic conditions on labour market outcomes: a time-lag panel analysis utilizing European SHARE dataset. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0211940.

Nevanperä N, Ala-Mursula L, Seitsamo J, Remes J, Auvinen J, Hopsu L, et al. Long-lasting obesity predicts poor work ability at midlife: a 15-year follow-up of the northern Finland 1966 birth cohort study. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57(12):1262–8.

Borys JM, Richard P, Ruault du Plessis H, Harper P, Levy E. Tackling health inequities and reducing obesity prevalence: the EPODE community-based approach. Ann Nutr Metab. 2016;68(Suppl 2):35–8.

Gardner B, Cane J, Rumsey N, Michie S. Behaviour change among overweight and socially disadvantaged adults: a longitudinal study of the NHS health trainer service. Psychol Health. 2012;27(10):1178–93.

Public Health England. Health Survey for England 2018. Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2018

Dowler E, Lambie-Mumford H. How can households eat in austerity? Challenges for social policy in the UK. Soc Policy Soc. 2015;14(3):417–28.

Hilmers A, Hilmers DC, Dave J. Neighborhood disparities in access to healthy foods and their effects on environmental justice. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1644–54.

Gabrys L, Michallik L, Thiel C, Vogt L, Banzer W. Effects of a structured physical-activity counseling and referral scheme in long-term unemployed individuals: a pilot accelerometer study. Behav Med. 2013;39(2):44–50.

Gough M. A couple-level analysis of participation in physical activity during unemployment. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:294–304.

Noordzij G, van Hooft EAJ, van Mierlo H, van Dam A, Born MP. The effects of a learning-goal orientation training on self-regulation: a field experiment among unemployed job seekers. Pers Psychol. 2013;66(3):723–55.

Kreuzfeld S, Preuss M, Weippert M, Stoll R. Health effects and acceptance of a physical activity program for older long-term unemployed workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86(1):99–105.

Yarborough CM, Brethauer S, Burton WN, Fabius RJ, Hymel P, Kothari S, et al. Obesity in the workplace: impact, outcomes, and recommendations. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(1):97–107.

Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity. 2009;17(5):941–64.

Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity stigma: important considerations for public health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(6):1019–28.

Dambrun M, Dubuy A-L. A positive psychology intervention among long-term unemployed people and its effects on psychological distress and well-being. J Employ Couns. 2014;51(2):75–88.

Price RH, Choi JN, Vinokur AD. Links in the chain of adversity following job loss: how financial strain and loss of personal control lead to depression, impaired functioning, and poor health. J Occup Health Psychol. 2002;7(4):302–12.

McLaughlin AP, Nikkheslat N, Hastings C, Nettis MA, Kose M, Worrell C, et al. The influence of comorbid depression and overweight status on peripheral inflammation and cortisol levels. Psychol Med. 2021;1-8.

Dombrowski SU, Knittle K, Avenell A, Araujo-Soares V, Sniehotta FF. Long term maintenance of weight loss with non-surgical interventions in obese adults: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2014;348(2646):1–12.

Hult M, Lappalainen K, Saaranen TK, Rasanen K, Vanroelen C, Burdorf A. Health-improving interventions for obtaining employment in unemployed job seekers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;1:1–66.

Ray Pawson TG, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review – a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(1):21–34.

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Pawson R. Development of methodological guidance, publication standards and training materials for realist and meta-narrative reviews: the RAMESES (realist and Meta-narrative evidence syntheses – Evolving Standards) project. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2014;2(30).

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(5):1005–22.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;134:103–12.

Aceves-Martins M, Robertson C, Cooper D, Avenell A, Stewart F, Aveyard P, et al. A systematic review of UK-based long-term nonsurgical interventions for people with severe obesity (BMI >/=35 kg m(−2) ). J Hum Nutr Diet. 2020;33(3):351–72.

Teixeira PJ, Carraca EV, Marques MM, Rutter H, Oppert JM, De Bourdeaudhuij I, et al. Successful behavior change in obesity interventions in adults: a systematic review of self-regulation mediators. BMC Med. 2015;13:84.

Audhoe SS, Hoving JL, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH. Vocational interventions for unemployed: effects on work participation and mental distress. A systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(1):1–13.

Koopman MY, Pieterse ME, Bohlmeijer ET, Drossaert CHC. Mental health promoting interventions for the unemployed: a systematic review of applied techniques and effectiveness. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2017;19(4):202–23.

Jagosh J. Realist synthesis for public health: building an ontologically deep understanding of how programs work, for whom, and in which contexts. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:361–72.

Greenhalgh J, Manzano A. Understanding ‘context’ in realist evaluation and synthesis. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2022;25(5):583–95.

Dalkin SM, Greenhalgh J, Jones D, Cunningham B, Lhussier M. What’s in a mechanism? Development of a key concept in realist evaluation. Implement Sci. 2015;10(49):1–7.

Rycroft-Malone J, Mccormack B, Hutchinson AM, Decorby K, Bucknall TK, Kent B, et al. Realist synthesis: illustrating the method for implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(33):1–10.

Coles E, Anderson J, Maxwell M, Harris FM, Gray NM, Milner G, et al. The influence of contextual factors on healthcare quality improvement initiatives: a realist review. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):94.

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gotzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869.

Wiltshire G, Ronkainen N. A realist approach to thematic analysis: making sense of qualitative data through experiential, inferential and dispositional themes. J Crit Real. 2021;20(2):159–80.

Brenninkmeijer V, Blonk RW. The effectiveness of the JOBS program among the long-term unemployed: a randomized experiment in the Netherlands. Health Promot Int. 2012;27(2):220–9.

Britt E, Sawatzky R, Swibaker K. Motivational interviewing to promote employment. J Employ Couns. 2018;55(4):176–89.

Chung LMY, Chung JWY, Chan APC. Building healthy eating knowledge and behavior: an evaluation of nutrition education in a skill training course for construction apprentices. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(23):1–14.

Creed PA, Bloxsome TD, Johnston K. Self-esteem and self-efficacy outcomes for unemployed individuals attending occupational skills training programs. Community Work Fam. 2001;4(3):285–303.

Eden D, Aviram A. Self-efficacy training to speed reemployment: helping people to help themselves. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(3):352–60.

Gonzalez-Marin P, Puig-Barrachina V, Bartoll X, Cortes-Franch I, Malmusi D, Clotet E, et al. Employment in the neighborhoods of Barcelona: health effects of an active labor market program in southern Europe. J Public Health. 2020;42(4):532–40.

Harrell JS, Johnston LF, Griggs TR, Schaefer P, Carr EG, McMurray RG, et al. An occupation based physical activity intervention program: improving fitness and decreasing obesity. AAOHN J. 1996;44(8):377–84.

Hodzic S, Ripoll P, Lira E, Zenasni F. Can intervention in emotional competences increase employability prospects of unemployed adults? J Vocat Behav. 2015;88:28–37.

Hulshof IL, Demerouti E, Le Blanc PM. A job search demands-resources intervention among the unemployed: effects on well-being, job search behavior and reemployment chances. J Occup Health Psychol. 2020;25(1):17–31.

Iseselo MK, Mosha IH, Killewo J, Sekei LH, Outwater AH. Can training interventions in entrepreneurship, beekeeping, and health change the mind-set of vulnerable young adults toward self-employment? A qualitative study from urban Tanzania. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):1–18.

Joseph LM, Greenberg MA. The effects of a career transition program on reemployment success in laid-off professionals. Consult Psychol J: Pract Res. 2001;53(3):169–81.

Limm H, Heinmuller M, Gundel H, Liel K, Seeger K, Salman R, et al. Effects of a health promotion program based on a train-the-trainer approach on quality of life and mental health of long-term unemployed persons. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:1–11.

Malmberg-Heimonen I, Vuori J. Activation or discouragement—the effect of enforced participation on the success of job-search training. Eur J Soc Work. 2005;8(4):451–67.

Malmberg-Heimonen IE, West BT, Vuori J. Long-term effects of research-based and practice-based job search interventions: an RCT reevaluation. Res Soc Work Pract. 2017;29(1):36–48.

Proudfoot J, Guest D, Carson J, Dunn G, Gray J. Effect of cognitive-behavioural training on job-finding among long-term unemployed people. Lancet. 1997;350(9071):96–100.

Reynolds C, Barry MM, Nic GS. Evaluating the impact of the winning new jobs programme on the re-employment and mental health of a mixed profile of unemployed people. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2012;12(2):32–41.

Robert S, Romanello L, Lesieur S, Kergoat V, Dutertre J, Ibanez G, et al. Effects of a systematically offered social and preventive medicine consultation on training and health attitudes of young people not in employment, education or training (NEETs): an interventional study in France. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0216226.

Shirom A, Vinokur A, Price R. Self-efficacy as a moderator of the effects of job-search workshops on re-employment: a field experiment. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2008;38(7):1778–804.

Stjernsward S, Bernce R, Ostman M. “Young women”: the meaning of a collaborative program supporting young women's rehabilitation and reintegration into the labor market. Soc Work Public Health. 2013;28(7):672–84.

van Ryn M, Vinokur AD. How did it work? An examination of the mechanisms through which an intervention for the unemployed promoted job-search behavior. Am J Community Psychol. 1992;20(5):577–97.

Vastamaki J, Moser K, Paul KI. How stable is sense of coherence? Changes following an intervention for unemployed individuals. Scand J Psychol. 2009;50(2):161–71.

Vinokur AD, Price RH, Schul Y. Impact of the JOBS intervention on unemployed workers varying in risk for depression. Am J Community Psychol. 1995;23(1):39–74.

Vuori J, Vesalainen J. Labour market interventions as predictors of re-employment, job seeking activity and psychological distress among the unemployed. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1999;72(4):523–38.

Vuori J, Silvonen J. The benefits of a preventive job search program on re-employment and mental health at 2-year follow-up. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2005;78(1):43–52.

Ahern AL, Wheeler GM, Aveyard P, Boyland EJ, Halford JCG, Mander AP, et al. Extended and standard duration weight-loss programme referrals for adults in primary care (WRAP): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10085):2214–25.

Allicock M, Ko L, van der Sterren E, Valle CG, Campbell MK, Carr C. Pilot weight control intervention among US veterans to promote diets high in fruits and vegetables. Prev Med. 2010;51(3-4):279–81.

Alves JG, Gale CR, Mutrie N, Correia JB, Batty GD. A 6-month exercise intervention among inactive and overweight favela-residing women in Brazil: the Caranguejo exercise trial. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(1):76–80.

Aoun S, Osseiran-Moisson R, Shahid S, Howat P, O’Connor M. Telephone lifestyle coaching: is it feasible as a behavioural change intervention for men? J Health Psychol. 2012;17(2):227–36.

Ash S, Reeves M, Bauer J, Dover T, Vivanti A, Leong C, et al. A randomised control trial comparing lifestyle groups, individual counselling and written information in the management of weight and health outcomes over 12 months. Int J Obes. 2006;30(10):1557–64.

Shams Azar L, Ghahari S, Shahbazi A, Ghezelseflo M. Effect of group schema therapy on physical self-concept and worry about weight and diet among obese women. J Res Health. 2018;8(6):548–54.

Beatty JA, Greene GW, Blissmer BJ, Delmonico MJ, Melanson KJ. Effects of a novel bites, steps and eating rate-focused weight loss randomised controlled trial intervention on body weight and eating behaviours. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2020;33(3):330–41.

Beintner I, Emmerich OLM, Vollert B, Taylor CB, Jacobi C. Promoting positive body image and intuitive eating in women with overweight and obesity via an online intervention: results from a pilot feasibility study. Eat Behav. 2019;34:1–5.

Benyamini Y, Geron R, Steinberg DM, Medini N, Valinsky L, Endevelt R. A structured intentions and action-planning intervention improves weight loss outcomes in a group weight loss program. Am J Health Promot. 2013;28(2):119–27.

Berg A, Frey I, Konig D, Predel HG. Exercise based lifestyle intervention in obese adults: results of the intervention study MOBILIs. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105(11):197–203.

Berli C, Stadler G, Inauen J, Scholz U. Action control in dyads: a randomized controlled trial to promote physical activity in everyday life. Soc Sci Med. 2016;163:89–97.

Bouhaidar CM, DeShazo JP, Puri P, Gray P, Robins JL, Salyer J. Text messaging as adjunct to community-based weight management program. Comput Inform Nurs. 2013;31(10):469–76.

Breslin G, Sweeney L, Shannon S, Murphy M, Hanna D, Meade M, et al. The effect of an augmented commercial weight loss program on increasing physical activity and reducing psychological distress in women with overweight or obesity: a randomised controlled trial. J Public Ment Health. 2019;19(2):145–57.

Brumby S, Chandrasekara A, Kremer P, Torres S, McCoombe S, Lewandowski P. The effect of physical activity on psychological distress, cortisol and obesity: results of the farming fit intervention program. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1).

Collins CE, Morgan PJ, Jones P, Fletcher K, Martin J, Aguiar EJ, et al. A 12-week commercial web-based weight-loss program for overweight and obese adults: randomized controlled trial comparing basic versus enhanced features. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(2):e57.

Chung LM, Law QP, Fong SS, Chung JW. Electronic dietary recording system improves nutrition knowledge, eating attitudes and habitual physical activity: a randomised controlled trial. Eat Behav. 2014;15(3):410–3.

Cleo G, Thomas R, Isenring E, Glasziou P. Do making habits or breaking habits influence weight loss and weight loss maintenance? A randomised controlled trial. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2019;13(1):1–13.

Dallow CB, Anderson J. Using self-efficacy and a transtheoretical model to develop a physical activity intervention for obese women. Am J Health Promot. 2003;17(6):373–81.

Dean DAL, Griffith DM, McKissic SA, Cornish EK, Johnson-Lawrence V. Men on the move-Nashville: feasibility and acceptability of a technology-enhanced physical activity pilot intervention for overweight and obese middle and older age African American men. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12(4):798–811.

del Rey-Moya LM, Castilla-Alvarez C, Pichiule-Castaneda M, Rico-Blazquez M, Escortell-Mayor E, Gomez-Quevedo R, et al. Effect of a group intervention in the primary healthcare setting on continuing adherence to physical exercise routines in obese women. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(15-16):2114–21.

Dombrowski SU, Sniehotta FF, Johnston M, Broom I, Kulkarni U, Brown J, et al. Optimizing acceptability and feasibility of an evidence-based behavioral intervention for obese adults with obesity-related co-morbidities or additional risk factors for co-morbidities: an open-pilot intervention study in secondary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(1):108–19.

Folta SC, Lichtenstein AH, Seguin RA, Goldberg JP, Kuder JF, Nelson ME. The strong women-healthy hearts program: reducing cardiovascular disease risk factors in rural sedentary, overweight, and obese midlife and older women. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(7):1271–7.

Garcia DO, Valdez LA, Aceves B, Bell ML, Humphrey K, Hingle M, et al. A gender- and culturally sensitive weight loss intervention for Hispanic men: results from the Animo pilot randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Behav. 2019;46(5):763–72.

Godino JG, Golaszewski NM, Norman GJ, Rock CL, Griswold WG, Arredondo E, et al. Text messaging and brief phone calls for weight loss in overweight and obese English- and Spanish-speaking adults: a 1-year, parallel-group, randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2019;16(9):e1002917.

Gram AS, Bonnelycke J, Rosenkilde M, Reichkendler M, Auerbach P, Sjodin A, et al. Compliance with physical exercise: using a multidisciplinary approach within a dose-dependent exercise study of moderately overweight men. Scand J Public Health. 2014;42(1):38–44.

Grey EB, Thompson D, Gillison FB. Effects of a web-based, evolutionary mismatch-framed intervention targeting physical activity and diet: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Behav Med. 2019;26(6):645–57.

Groh CJ, Urbancic JC. The impact of a lifestyle change program on the mental health of obese under-served African American women. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015;29(2):76–82.

Hardcastle S, Taylor A, Bailey M, Castle R. A randomised controlled trial on the effectiveness of a primary health care-based counselling intervention on physical activity, diet and CHD risk factors. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70(1):31–9.

Hardcastle SJ, Taylor AH, Bailey MP, Harley RA, Hagger MS. Effectiveness of a motivational interviewing intervention on weight loss, physical activity and cardiovascular disease risk factors: a randomised controlled trial with a 12-month post-intervention follow-up. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:1–16.

Hutchesson MJ, Collins CE, Morgan PJ, Watson JF, Guest M, Callister R. Changes to dietary intake during a 12-week commercial web-based weight loss program: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68(1):64–70.

Jane M, Hagger M, Foster J, Ho S, Kane R, Pal S. Effects of a weight management program delivered by social media on weight and metabolic syndrome risk factors in overweight and obese adults: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):1–20.

Kegler MC, Haardorfer R, Alcantara IC, Gazmararian JA, Veluswamy JK, Hodge TL, et al. Impact of improving home environments on energy intake and physical activity: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):143–52.

Keller C, Treviño RP. Effects of two frequencies of walking on cardiovascular risk factor reduction in Mexican American women. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(5):390–401.

Kleist B, Wahrburg U, Stehle P, Schomaker R, Greiwing A, Stoffel-Wagner B, et al. Moderate walking enhances the effects of an energy-restricted diet on fat mass loss and serum insulin in overweight and obese adults in a 12-week randomized controlled trial. J Nutr. 2017;147(10):1875–84.

Kraushaar LE, Kramer A. Web-enabled feedback control over energy balance promotes an increase in physical activity and a reduction of body weight and disease risk in overweight sedentary adults. Prev Sci. 2014;15(4):579–87.

Lee CY, Lee H, Jeon KM, Hong YM, Park SH. Self-management program for obesity control among middle-aged women in Korea: a pilot study. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2011;8(1):66–75.

Lutes LD, Daiss SR, Barger SD, Read M, Steinbaugh E, Winett RA. Small changes approach promotes initial and continued weight loss with a phone-based follow-up: nine-month outcomes from ASPIRES II. Am J Health Promot. 2012;26(4):235–8.

Marquez B, Wing RR. Feasibility of enlisting social network members to promote weight loss among Latinas. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(5):680–7.

Mayer VL, Vangeepuram N, Fei K, Hanlen-Rosado EA, Arniella G, Negron R, et al. Outcomes of a weight loss intervention to prevent diabetes among low-income residents of East Harlem, New York. Health Educ Behav. 2019;46(6):1073–82.

McRobbie H, Hajek P, Peerbux S, Kahan BC, Eldridge S, Trepel D, et al. Randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of a task-based weight management group programme. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):365.

Mohamed W, Azlan A, Talib RA. Benefits of community gardening activity in obesity intervention: findings from F.E.A.T Programme. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci J. 2018;6(3):700–10.

Kassim MSA, Manaf MRA, Nor NSM, Ambak R. Effects of lifestyle intervention towards obesity and blood pressure among housewives in Klang Valley: a quasi-experimental study. Malays J Med Sci. 2017;24(6):83–91.

Mummah S, Robinson TN, Mathur M, Farzinkhou S, Sutton S, Gardner CD. Effect of a mobile app intervention on vegetable consumption in overweight adults: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):125.

Park MJ, Kim HS, Kim KS. Cellular phone and internet-based individual intervention on blood pressure and obesity in obese patients with hypertension. Int J Med Inform. 2009;78(10):704–10.

Silina V, Tessma MK, Senkane S, Krievina G, Bahs G. Text messaging (SMS) as a tool to facilitate weight loss and prevent metabolic deterioration in clinically healthy overweight and obese subjects: a randomised controlled trial. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2017;35(3):262–70.

Sniehotta FF, Evans EH, Sainsbury K, Adamson A, Batterham A, Becker F, et al. Behavioural intervention for weight loss maintenance versus standard weight advice in adults with obesity: a randomised controlled trial in the UK (NULevel trial). PLoS Med. 2019;16(5):e1002793.

Solbrig L, Whalley B, Kavanagh DJ, May J, Parkin T, Jones R, et al. Functional imagery training versus motivational interviewing for weight loss: a randomised controlled trial of brief individual interventions for overweight and obesity. Int J Obes. 2019;43(4):883–94.

Tapsell LC, Batterham MJ, Thorne RL, O'Shea JE, Grafenauer SJ, Probst YC. Weight loss effects from vegetable intake: a 12-month randomised controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68(7):778–85.

Tapsell LC, Thorne R, Batterham M, Russell J, Ciarrochi J, Peoples G, et al. Feasibility of a community-based interdisciplinary lifestyle intervention trial on weight loss (the HealthTrack study). Nutr Diet. 2015;73(4):321–8.

Uemura M, Hayashi F, Ishioka K, Ihara K, Yasuda K, Okazaki K, et al. Obesity and mental health improvement following nutritional education focusing on gut microbiota composition in Japanese women: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. 2019;58(8):3291–302.

Watkins PL, Taylor VH, Ebbeck V, Levy SS. Overcoming weight bias: promoting physical activity and psychosocial health. Ethn Inequalities Health Soc Care. 2014;7(4):187–97.

Whitelock V, Kersbergen I, Higgs S, Aveyard P, Halford JCG, Robinson E. A smartphone based attentive eating intervention for energy intake and weight loss: results from a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):611.

Whitham C, Mellor DD, Goodwin S, Reid M, Atkin SL. Weight maintenance over 12 months after weight loss resulting from participation in a 12-week randomised controlled trial comparing all meal provision to self-directed diet in overweight adults. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27(4):384–90.

Wyke S, Bunn C, Andersen E, Silva MN, van Nassau F, McSkimming P, et al. The effect of a programme to improve men's sedentary time and physical activity: the European fans in training (EuroFIT) randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2019;16(2):1–25.

Young MD, Plotnikoff RC, Collins CE, Callister R, Morgan PJ. Impact of a male-only weight loss maintenance programme on social-cognitive determinants of physical activity and healthy eating: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Health Psychol. 2015;20(4):724–44.

Linda Bacon LA. Weight science: evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift. Nutr J. 2011;10(9):1–13.

Meadows P. What works with tackling worklessness? 2006:1-72. Available at: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/gla_migrate_files_destination/worklessness.pdf

Johns DJ, Hartmann-Boyce J, Jebb SA, Aveyard P. Behavioural weight management review: diet or exercise interventions vs combined behavioral weight management programs: a systematic review and meta-analysis of direct comparisons. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(10):1557–68.

Baetge C, Earnest CP, Lockard B, Coletta AM, Galvan E, Rasmussen C, et al. Efficacy of a randomized trial examining commercial weight loss programs and exercise on metabolic syndrome in overweight and obese women. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2017;42(2):216–27.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ella Baker, our internship student at Bournemouth University for help with screening and data extraction as part of the study.

Funding

This work is funded by grants from the EU Interreg European Regional Development Fund (ASPIRE 191). The funders had no role, in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of this report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SDA, JM, L-AF jointly conceived the study; SDA, DW conducted the research; SDA led the writing of this paper with contributions and revisions from JM, L-AF and WT. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors (SDA, DW, WT, JM and L-AF) declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Amenyah, S.D., Waters, D., Tang, W. et al. Systematic realist synthesis of health-related and lifestyle interventions designed to decrease overweight, obesity and unemployment in adults. BMC Public Health 22, 2100 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14518-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14518-6